Donepezil and Concurrent Sertraline Treatment Is Associated With Increased Hippocampal Volume in a Patient With Depression

To the Editor: Donepezil is a widely used acetylcholinesterase inhibitor that has been shown to slow the progress of cognitive impairment in patients with mild-to-moderate Alzheimer’s disease. We observed a case of refractory depression with a hippocampal volume reduction identical to that commonly observed in early-onset Alzheimer’s disease. Addition of donepezil in our case led to complete remission of depression that concurred with a robust increase in hippocampal volume. Herein, we report this intriguing case.

Case report. Ms A, a 44-year-old woman with a 4-year history of depression, was admitted for the second time to the University Hospital of the Hamamatsu University School of Medicine, Hamamatsu, Japan, in May 2007. Over the refractory course of the disorder, she had responded poorly to various treatments, including recommended maximum doses of paroxetine, clomipramine, lithium carbonate, and a combination therapy of paroxetine and olanzapine, as well as cognitive-behavioral therapy that was administered during her previous first hospitalization. At the current admission, she reported depressive mood with prominent anxiety, diminished interest/pleasure, slowness of thought, forgetfulness, loss of energy, inability to concentrate, and insomnia. She had no history of head trauma, seizure, or loss of consciousness. Results of her neurologic and medical examinations, laboratory tests, and electroencephalogram were all normal. She met the DSM-IV-TR criteria for major depressive disorder and scored 20 on the Hamilton Depression Rating Scale (HDRS).1

At routine cognitive assessment, she was found to have deficits in global cognitive function, with an IQ of 67 based on the Wechsler Adult Intelligence Scale-Third Edition.2 An impairment of verbal episodic memory was also evident; on the Wechsler Memory Scale-Revised (WMS-R),3 immediate recall of logical memory was 13 (normal range, 17-31) and delayed recall of logical memory was 5 (normal range, 11-29). Since her IQ as assessed during her first hospitalization was 111, cognitive decline was apparent (a 40% decline in IQ).

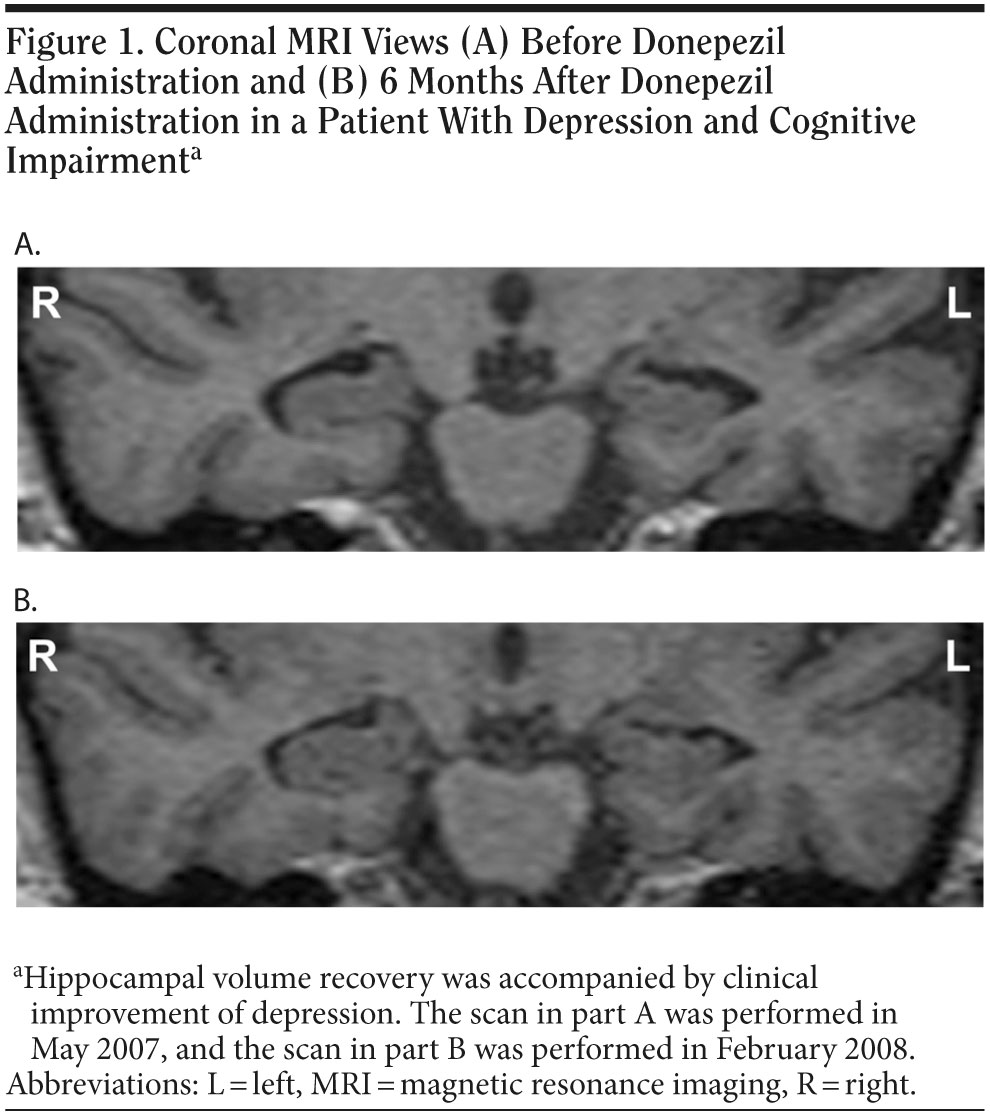

Scanning with a GE Signa1 5-T magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) scanner (General Electric, Milwaukee, Wisconsin) revealed noticeable morphological changes, particularly in the hippocampal area, although no abnormality (ie, no atrophy in the hippocampus) had been noted on a routine MRI scan at Ms A’s first admission. On the basis of this finding, we performed volumetric analyses as described elsewhere.4 A marked hippocampal volume reduction was observed bilaterally, especially on the left (hippocampal volume [mL] adjusted for total intracranial volume [L]; left: 1.64 mL/L, right: 1.84 mL/L) (Figure 1A, Table 1). Although she did not meet standard criteria for Alzheimer’s disease (ie, National Institute of Neurological and Communicative Disorders and Stroke/Alzheimer’s Disease and Related Disorders Association [NINCDS-ADRDA] criteria) owing to the presence of depression, her total hippocampal volume loss was identical to that of the early stage of Alzheimer’s disease.5 On the basis of Ms A’s salient cognitive deterioration, in particular impairment of verbal episodic memory, along with corresponding brain structure abnormalities, potential conversion to early-onset Alzheimer’s disease was suspected.6,7 Donepezil administration was thus initiated.

In September 2007, treatment was started with donepezil at a dose of 10 mg/d. For Ms A’s depressive symptoms, sertraline was started in March 2007, titrated up to 150 mg/d during the current admission, and maintained throughout the donepezil challenge. Surprisingly, during the 2-month period of treatment with donepezil, her deficits in cognition were drastically alleviated (IQ = 90; WMS-R immediate recall of logical memory = 21, delayed recall of logical memory = 14), in parallel with a clinically significant improvement in depression (HDRS score = 10). Simultaneously, she achieved robust volume recovery in the bilateral hippocampus relative to the previous scan (left: 1.93 mL/L [+17.7%], right: 2.05 mL/L [+11.7%]) (Table 1). She was discharged from the hospital.

In February 2008, the patient’s depressive symptoms were fully ameliorated (HDRS score = 3), and further hippocampal volume recovery was noted on the follow-up MRI (left: 2.07 mL/L, right: 2.17 mL/L, corresponding to increases of 26.5% and 18.1%, respectively, relative to the first scan; Figure 1B, Table 1). No recurrence of depression was observed over the subsequent 16-week period.

In the present case, the patient developed severe cognitive impairment and had a significant volume reduction of the hippocampus (> 25% for the left); hence, she was suspected of having early-onset Alzheimer’s disease. However, after successful treatment with donepezil, which has previously been shown to merely slow the progress of cognitive impairment in Alzheimer’s disease, she achieved complete remission of cognitive impairment, hippocampal volume loss, and depressive symptoms. From such a recovery, it is concluded that all of the phenomena (the hippocampal volume loss and cognitive impairment) can be ascribed to depression (ie, pseudodementia8). It is of note, however, that the depression-associated loss in hippocampal volume has previously been reported to be less than 19%,9 which the present case exceeded (ie, > 25%).

A previous study reported that donepezil combined with antidepressant treatment temporarily, in the first few months of treatment, improves verbal episodic memory in elderly patients with depression plus cognitive impairment.10 Another study has demonstrated that donepezil monotherapy improves affective symptoms of patients with mild Alzheimer’s disease, whereas it shows no beneficial effect on cognitive dysfunction.11 To the best of our knowledge, there has, thus far, been no clinical report showing the ability of donepezil plus a selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor to reverse both hippocampal atrophy and considerable cognitive deficits. In the present case, such a combination treatment was found effective in treating depression with a volume loss in the hippocampus larger than previously reported and a substantial level of cognitive impairment identical to that in early-onset Alzheimer’s disease.

Our experience with the present case suggests that although further studies are needed to evaluate the effectiveness of donepezil per se in the treatment of depression, donepezil may have a beneficial effect in relatively young adults who have a severe and refractory course of depression along with salient cognitive impairment and a hippocampal volume reduction.

References

1. Hamilton M. A rating scale for depression. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 1960;23:56-62.

2. Wechsler D. Wechsler Adult Intelligence Scale-III. San Antonio, TX: The Psychological Corporation; 1997.

3. Wechsler D. Wechsler Memory Scale-Revised. New York, NY: Psychological Corporation; 1987.

4. Sheline YI, Wang PW, Gado MH, et al. Hippocampal atrophy in recurrent major depression. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1996;93(9):3908-3913. PubMed doi:10.1073/pnas.93.9.3908

5. Krasuski JS, Alexander GE, Horwitz B, et al. Volumes of medial temporal lobe structures in patients with Alzheimer’s disease and mild cognitive impairment (and in healthy controls). Biol Psychiatry. 1998;43(1):60-68. PubMed doi:10.1016/S0006-3223(97)00013-9

6. Barnes J, Whitwell JL, Frost C, et al. Measurements of the amygdala and hippocampus in pathologically confirmed Alzheimer disease and frontotemporal lobar degeneration. Arch Neurol. 2006;63(10):1434-1439. PubMed doi:10.1001/archneur.63.10.1434

7. Rémy F, Mirrashed F, Campbell B, et al. Verbal episodic memory impairment in Alzheimer’s disease: a combined structural and functional MRI study. Neuroimage. 2005;25(1):253-266. PubMed doi:10.1016/j.neuroimage.2004.10.045

8. Wells CE. Pseudodementia. Am J Psychiatry. 1979;136(7):895-900. PubMed

9. Sheline YI. 3D MRI studies of neuroanatomic changes in unipolar major depression: the role of stress and medical comorbidity. Biol Psychiatry. 2000;48(8):791-800. PubMed doi:10.1016/S0006-3223(00)00994-X

10. Pelton GH, Harper OL, Tabert MH, et al. Randomized double-blind placebo-controlled donepezil augmentation in antidepressant-treated elderly patients with depression and cognitive impairment: a pilot study. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2008;23(7):670-676. PubMed doi:10.1002/gps.1958

11. Requena C, López Ibor MI, Maestú F, et al. Effects of cholinergic drugs and cognitive training on dementia. Dement Geriatr Cogn Disord. 2004;18(1):50-54. PubMed doi:10.1159/000077735

Author affiliations: Department of Psychiatry and Neurology (Drs Suda, Suyama, and Mori) and Research Center for Child Mental Development (Drs Suda, Sugihara, and Takei), Hamamatsu University School of Medicine, Hamamatsu, Japan; and Division of Psychological Medicine, Institute of Psychiatry, King’s College London, London, United Kingdom (Drs Sugihara and Takei). Potential conflicts of interest: None reported. Funding/support: None reported.

doi:10.4088/JCP.09l05101gry

© Copyright 2010 Physicians Postgraduate Press, Inc.