Prolonged exposure (PE) is a gold-standard trauma-focused therapy1; however, clinical trials of trauma-based therapies in the military and veteran populations showed that up to 50% of participants failed to attain clinically meaningful symptom improvement.2 Emerging research indicates that PE efficacy may be improved by the use of adjunctive medications. The efficacy of single and repeated ketamine administration in posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) seems comparable with that in depression. Below, we present pilot data on the feasibility of combining standardized PE therapy with repeated ketamine administration in PTSD.

Methods

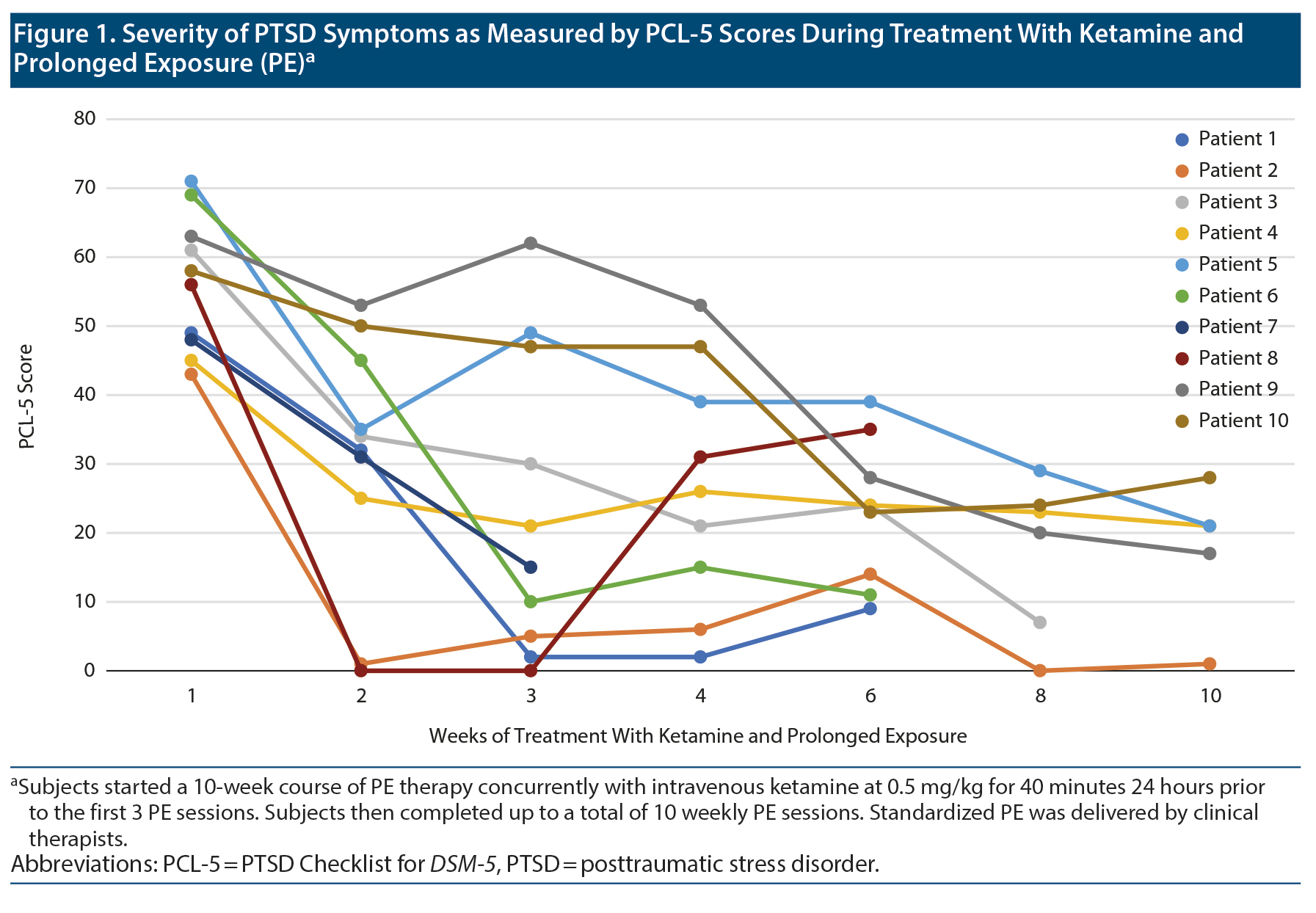

In a 10-week pilot conducted April-June 2019, veterans aged 18-75 years with chronic (> 6 months) and at least moderate PTSD (Clinician-Administered PTSD Scale for DSM-5 [CAPS-5] score ≥ 23 and PTSD Checklist for DSM-5 [PCL-5] score > 33) received intravenous (IV) ketamine (0.5 mg/kg) 24 hours prior to weekly PE for the first 3 weeks followed by up to 7 additional PE sessions. PE was delivered by nationally certified clinical therapists. Exclusion criteria were < 6 months of alcohol/substance use disorder, moderate/severe traumatic brain injury, bipolar disorder, or psychosis. Concurrent psychotropics were stable ≥ 4 weeks. The primary outcome was the change in CAPS-5 scores from baseline to the last PE session administered by an independent evaluator. Linear mixed model with intent-to-treat analysis included baseline CAPS-5 score, time as fixed effects, and random patient effect. Secondary outcomes, which included the Montgomery-Asberg Depression Rating Scale (MADRS), PCL-5, and Clinical Global Impression-Severity of Illness scale (CGI-S), were measured at baseline and weeks 1, 2, 3, 4, 6, 8, and 10. Informed consent was obtained from all participants. The study was approved by the Minneapolis Health Care System institutional review board and registered in ClinicalTrials.gov (NCT03960658).

Results

In 4 months, out of 12 subjects who provided consent, 10 completed treatment infusions with at least 1 follow-up PCL-5 (N = 10) or CAPS-5 (N = 9) assessment. Demographic and clinical characteristics are shown in Supplementary Table 1. PCL-5 scores for each patient at several weeks of treatment are shown in Figure 1, and complete PE sessions and pre- and posttreatment scores of CAPS-5, PCL-5, MADRS, and CGI-S are shown in Supplementary Table 2. Scores significantly decreased from baseline to end of treatment in CAPS-5 (t11 = 4.21, P = .001, -15.25 [95% CI, 7.27-23.23], d = 1.21), PCL-5 (t11 = 6.35, P < .001, -30.75 [20.09-41.41], d = 1.83), and MADRS (t11 = 4.68, P = .001, -11.5 [6.09-16.91], d = 1.35). After controlling for mean change in MADRS score over time, changes in total PCL-5 scores (F1,10 = 5.69, P = .038, h2 = 0.36) and PCL-5 Avoidance (F1,10 = 6.31, P = .031, h2 = 0.36) remained significant. However, changes in PCL-5 Intrusion (F1,10 = 4.48, P = .06, h2 = 0.31), Arousal (F1,10 = 1.25, P = .29, h2 = 0.11), and Negative mood and cognition (F1,10 = 3.83, P = .079, h2 = 0.28), as well as CAPS-5 (F1,10 = 1.18, P = .30, h2 = 0.11), were no longer significant.

Discussion

This small, open-label, proof-of-concept study suggests that repeated IV ketamine administration can be concurrently used with standardized PE therapy to treat PTSD. Previously, a single infusion of ketamine significantly decreased PTSD symptoms 24 hours postinfusion compared to midazolam.3 Findings with repeat open-label IV ketamine administration in comorbid PTSD and refractory depression suggested that ketamine increases the efficacy for both PTSD and depressive symptoms beyond a single infusion.4

Clinical studies have demonstrated the feasibility of combining IV ketamine and cognitive-behavioral therapy in obsessive-compulsive disorder5 and treatment-resistant depression.6 PE efficacy may be improved through medications that target 1 or more mechanisms.7 Ketamine could augment the biological processes of extinction memory. In mice models of PTSD, a single dose of ketamine followed by extinction training enhances the recall of extinction learning and decreases fear renewal.8 Ketamine plus extinction exposure increases synaptic protein promoter and neuronal activation in the medial prefrontal cortex,8 exerting a possible top-down inhibitory drive over excitatory responses of fear conditioning such as the amygdala.

As an alternative, early gains by ketamine’s rapid antidepressant and anxiolytic effects can strengthen confidence in the therapeutic approach, improve rapport, and increase treatment adherence. Rapid improvement in depression is associated with lower rate of dropout and lower posttreatment severity score during PTSD treatment.9 A potential backfire of this rapid response is reducing the motivation to complete PE. Given preliminary findings, larger randomized clinical trials should prove whether ketamine has a synergistic effect over trauma-based therapy for PTSD.

Published online: November 10, 2020.

Potential conflicts of interest: None.

Funding/support: This work was supported by the United States Department of Veterans Affairs Clinical Sciences Research and Development Merit Review Award (grant I01 CX001191 to Dr Shiroma).

Role of the sponsor: The funder had no role in the design and conduct of the study; collection, management, analysis, and interpretation of the data, preparation, review, or approval of the manuscript; and decision to submit the manuscript for publication.

Previous presentation: Presented as a poster at the 75th Annual Meeting of the Society of Biological Psychiatry; New York, New York; April 30-May 2, 2020.

Acknowledgments: The authors thank Emily Voeller, PhD; Eliza McManus, PhD; Matthew Kaler, PhD; Eric Baltutis, BS; Debra Condon, RN; Amber Hoeschler, RN; and the nursing staff and clerkship personnel of the 2E Unit at Minneapolis VA Health Care System for providing technical and clinical support. No compensation was received outside of usual salary.

Supplementary material: See accompanying pages.

REFERENCES

1.Powers MB, Halpern JM, Ferenschak MP, et al. A meta-analytic review of prolonged exposure for posttraumatic stress disorder. Clin Psychol Rev. 2010;30(6):635-641. PubMed CrossRef

2.Steenkamp MM, Litz BT, Hoge CW, et al. Psychotherapy for military-related PTSD: a review of randomized clinical trials. JAMA. 2015;314(5):489-500. PubMed CrossRef

3.Feder A, Parides MK, Murrough JW, et al. Efficacy of intravenous ketamine for treatment of chronic posttraumatic stress disorder: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA Psychiatry. 2014;71(6):681-688. PubMed CrossRef

4.Albott CS, Lim KO, Forbes MK, et al. Efficacy, safety, and durability of repeated ketamine infusions for comorbid posttraumatic stress disorder and treatment-resistant depression. J Clin Psychiatry. 2018;79(3):17m11634. PubMed CrossRef

5.Rodriguez CI, Wheaton M, Zwerling J, et al. Can exposure-based CBT extend the effects of intravenous ketamine in obsessive-compulsive disorder? an open-label trial. J Clin Psychiatry. 2016;77(3):408-409. PubMed CrossRef

6.Wilkinson ST, Wright D, Fasula MK, et al. Cognitive behavior therapy may sustain antidepressant effects of intravenous ketamine in treatment-resistant depression. Psychother Psychosom. 2017;86(3):162-167. PubMed CrossRef

7.Dunlop BW, Mansson E, Gerardi M. Pharmacological innovations for posttraumatic stress disorder and medication-enhanced psychotherapy. Curr Pharm Des. 2012;18(35):5645-5658. PubMed CrossRef

8.Girgenti MJ, Ghosal S, LoPresto D, et al. Ketamine accelerates fear extinction via mTORC1 signaling. Neurobiol Dis. 2017;100:1-8. PubMed CrossRef

9.Keller SM, Feeny NC, Zoellner LA. Depression sudden gains and transient depression spikes during treatment for PTSD. J Consult Clin Psychol. 2014;82(1):102-111. PubMed CrossRef

aMental Health Service Line, Minneapolis VA Health Care System, Minneapolis, Minnesota

bDepartment of Psychiatry, University of Minnesota, Minneapolis, Minnesota

cUniversity of Minnesota Medical School, Minneapolis, Minnesota

dCenter for Chronic Disease Outcomes Research, Minneapolis, Minnesota

eWomen’s Health Sciences Division of the National Center for PTSD, Boston, Massachusetts

fDepartment of Medicine, University of Minnesota, Minneapolis, Minnesota

*Corresponding author: Paulo R. Shiroma, MD, One Veterans Dr 116-A, Minneapolis, MN 55417 ([email protected]).

J Clin Psychiatry 2020;81(6):20l13406

To cite: Shiroma PR, Thuras P, Wels J, et al. A proof-of-concept study of subanesthetic intravenous ketamine combined with prolonged exposure therapy among veterans with posttraumatic stress disorder. J Clin Psychiatry. 2020;81(6):20l13406.

To share: https://doi.org/10.4088/JCP.20l13406

© Copyright 2020 Physicians Postgraduate Press, Inc.

This PDF is free for all visitors!