Because this piece does not have an abstract, we have provided for your benefit the first 3 sentences of the full text.

Ms A is an 87-year-old right-handed white woman who presented with her family to the memory clinic at Banner Alzheimer’s Institute for evaluation and treatment of cognitive impairment. She was accompanied by her husband and one of her daughters, both of whom were reliable informants. She and her family noted problems starting approximately 3 years prior to the evaluation, including trouble keeping track of information, word-finding difficulty, and occasionally repeating questions. These cognitive symptoms gradually worsened over the next 2 years, leading to functional impairment about 1 year before the evaluation.

BANNER ALZHEIMER’ S INSTITUTE

The Banner Alzheimer’s Institute located in Phoenix, Arizona, has an unusually ambitious mission: to end Alzheimer’s disease without losing a generation, set a new standard of care for patients and families, and forge a model of collaboration in biomedical research. The Institute provides high-level care and treatment for patients affected by Alzheimer’s disease, dementia, and related disorders. In addition, the Institute offers extensive support services for families and many unique and rewarding research opportunities.

The Banner Alzheimer’s Institute Case Conference is a weekly event in which physicians and staff discuss challenging and/or teaching cases of patients seen at the Institute’s Memory Disorders Clinic. These conferences are attended by a multidisciplinary group that includes Banner Alzheimer’s Institute dementia specialists, community physicians (internal medicine, family medicine, and radiology), physician assistants, social workers, nurses, medical students, residents, and fellows.

Prim Care Companion CNS Disord 2018;20(3):18alz02292

To cite: Weidman DA, Burke AD, Eschbacher JM, et al. To scan or not to scan: horses and zebras. Prim Care Companion CNS Disord. 2018;20(3):18alz02292.

To share: https://doi.org/10.4088/PCC.18alz02292

© Copyright 2018 Physicians Postgraduate Press, Inc.

Submitted: March 6, 2008; accepted April 19, 2018.

Published online: June 28, 2018.

David A. Weidman, MD, is a neurologist and dementia specialist at Banner Alzheimer’s Institute and a clinical assistant professor of neurology at the University of Arizona College of Medicine, Phoenix.

Anna D. Burke, MD, is a geriatric psychiatrist and director of neuropsychiatry at Barrow Neurological Institute and a clinical assistant professor of psychiatry at the University of Arizona College of Medicine, Phoenix.

Jennifer M. Eschbacher, MD, is chair of the Department of Neuropathology at Barrow Neurological Institute, Phoenix, Arizona.

Jacquelynn Copeland, PhD, is a neuropsychologist at Banner Alzheimer’s Institute, Phoenix, Arizona.

Michele Grigaitis-Reyes, NP, is a nurse practitioner at Banner Alzheimer’s Institute, Phoenix, Arizona.

William J. Burke, MD, is a geriatric psychiatrist and the director of the Stead Family Memory Clinic of Banner Alzheimer’s Institute and a research professor of psychiatry at the University of Arizona College of Medicine, Phoenix.

*Corresponding author: David A. Weidman, MD, Banner Alzheimer’s Institute, 901 E Willetta St, Phoenix, AZ 85006 ([email protected]).

CME Background

Articles are selected for credit designation based on an assessment of the educational needs of CME participants, with the purpose of providing readers with a curriculum of CME articles on a variety of topics throughout each volume. This special series of case reports about dementia was deemed valuable for educational purposes by the Publisher, Editor in Chief, and CME Institute staff. Activities are planned using a process that links identified needs with desired results.

To obtain credit, read the article, correctly answer the questions in the Posttest, and complete the Evaluation.

CME Objective

After studying this article, you should be able to:

- Use neuroimaging to rule out structural abnormalities in the evaluation of patients meeting clinical criteria for a major neurocognitive disorder

Accreditation Statement

The CME Institute of Physicians Postgraduate Press, Inc., is accredited by the Accreditation Council for Continuing Medical Education to provide continuing medical education for physicians.

Credit Designation

The CME Institute of Physicians Postgraduate Press, Inc., designates this journal-based CME activity for a maximum of 1.0 AMA PRA Category 1 Creditâ„¢. Physicians should claim only the credit commensurate with the extent of their participation in the activity.

Note: The American Academy of Physician Assistants (AAPA) accepts certificates of participation for educational activities certified for AMA PRA Category 1 Creditâ„¢ from organizations accredited by ACCME or a recognized state medical society. Physician assistants may receive a maximum of 1.0 hour of Category I credit for completing this program.

Release, Expiration, and Review Dates

This educational activity was published in June 2018 and is eligible for AMA PRA Category 1 Creditâ„¢ through June 30, 2020. The latest review of this material was June 2018.

Financial Disclosure

All individuals in a position to influence the content of this activity were asked to complete a statement regarding all relevant personal financial relationships between themselves or their spouse/partner and any commercial interest. The CME Institute has resolved any conflicts of interest that were identified. In the past year, Larry Culpepper, MD, MPH, Editor in Chief, has been a consultant for Alkermes, Jazz, Lundbeck, Merck, and Sunovion; has been a stock shareholder of M-3 Information; and has received royalties from UpToDate and Oxford University Press. No member of the CME Institute staff reported any relevant personal financial relationships.

HISTORY OF PRESENTING ILLNESS

Ms A is an 87-year-old right-handed white woman who presented with her family to the memory clinic at Banner Alzheimer’s Institute for evaluation and treatment of cognitive impairment. She was accompanied by her husband and one of her daughters, both of whom were reliable informants. She and her family noted problems starting approximately 3 years prior to the evaluation, including trouble keeping track of information, word-finding difficulty, and occasionally repeating questions. These cognitive symptoms gradually worsened over the next 2 years, leading to functional impairment about 1 year before the evaluation. Most notably, she was having difficulty using technology, in particular, the ability to operate her iPad, which she had used and enjoyed independently for several years. She could no longer manage household finances, as she had missed payments. Her family felt that she was continuing to drive safely within a familiar environment. She shopped, cooked, and operated a microwave with no difficulty and took several medications with no assistance. She was able to read and write. Her gait appeared more cautious, but she had not fallen. Although she had a longstanding history of depression, both Ms A and her family felt that her mood was euthymic with antidepressant medication. However, she did admit to low energy some weeks. Anxiety was not evident. Symptoms did not worsen under stress or late in the day. She was eating and sleeping well. Three months prior to this evaluation, Ms A’s primary care physician felt that the main cause of the mild cognitive impairment was depression.

PAST MEDICAL HISTORY

Ms A has a history of anxiety, depression, asthma, remote breast cancer, hyperlipidemia, osteoarthritis, osteopenia, and urinary frequency. Her surgical history includes knee replacement and mastectomy.

MEDICATION ALLERGIES

Ms A reported no known medication allergies.

MEDICATIONS

Ms A’s current medications included duloxetine 90 mg/d, tolterodine long acting 4 mg, pravastatin 20 mg/d, ranitidine 150 mg/d, zoledronic acid intravenous yearly, fluticasone 44 μg when necessary, albuterol 90 μg when necessary, a multivitamin, and a calcium/vitamin D3 combination pill. Ms A remained independent, taking medications on her own, and needed no assistance or reminders from her family.

SOCIAL HISTORY

Ms A has 12 years of education and worked for more than 40 years. She lives at home with her husband and has 3 supportive children. Her daughter, who was present at the initial evaluation, spends the winter months in Arizona and sees Ms A on a daily basis during that time.

SUBSTANCE USE HISTORY

Ms A never smoked cigarettes, and there was no history of alcohol or illicit drug use.

FAMILY HISTORY

Ms A reported that her identical twin sister was developing mild memory difficulties. Her mother suffered from clinical depression and committed suicide when Ms A was young. There is no known family history of Alzheimer’s disease.

On the basis of the information so far, what would you expect to see on the neurologic examination?

Your Colleagues Who Attended the Banner Alzheimer’s Institute Case Conference Answered as Follows:

| A. Normal | 88% |

| B. Objective, nonfocal neurologic findings (eg, frontal release signs) | 8% |

| C. Focal neurologic findings | 4% |

| D. Insufficient information provided thus far | 0% |

PHYSICAL AND NEUROLOGIC EXAMINATION

Ms A was a well-groomed woman with a thin build but no recent weight loss. She weighed 121 lb, and her blood pressure was 132/72 mm Hg. The examination revealed mild kyphoscoliosis of the thoracic spine, diminished range of motion of both hips, and a mildly arthritic (stiff) gait pattern, narrow-based with smooth turning and normal stride length. The Romberg sign was negative. She showed normal comportment, facial expression, thought process, degree of eye contact, and level of engagement throughout the interview and examination. No abnormalities were seen on sensory, motor, coordination, deep tendon reflex, or cranial nerve testing. No frontal release signs or nonfocal neurologic findings were present.

LABORATORY AND RADIOLOGY RESULTS

Laboratory results available at the time of the initial visit included complete blood count with differential, comprehensive metabolic panel, vitamin B12 level, thyroid-stimulating hormone level, and lipid panel, all of which were within normal limits. Brain imaging was not done prior to the initial presentation.

On the basis of the information so far, do you think a major neurocognitive disorder is present?

Your Colleagues Who Attended the Banner Alzheimer’s Institute Case Conference Answered as Follows:

| A. Yes | 32% |

| B. No | 24% |

| C. Not enough information provided | 44% |

Almost half of the participants believed that insufficient information was provided thus far. Criteria for a major neurocognitive disorder include quantified clinical assessment and objective signs of cognitive impairment—symptoms alone are not sufficient to make this diagnosis.

The DSM-5 (American Psychiatric Association, 2013) defines a major neurocognitive disorder as follows:

- Evidence of significant cognitive decline from a previous level of performance in 1 area or more of cognitive domains (complex attention, executive function, learning and memory, language, perceptual-motor, or social cognition) based on:

- Concern of the individual, a knowledgeable informant, or the clinician that there has been a significant decline in cognitive function and

- Substantial impairment in cognitive performance, preferably documented by standardized neuropsychological testing or, in its absence, another quantified clinical assessment.

- The cognitive deficits interfere with independence in everyday activities.

- The cognitive deficits do not occur exclusively in the context of a delirium

- The cognitive deficits are not better explained by another mental disorder.

On the basis of the information so far, what would you expect the MMSE score to be?

Your Colleagues Who Attended the Banner Alzheimer’s Institute Case Conference Answered as Follows:

| A. 26-30 | 0% |

| B. 21-25 | 91% |

| C. 16-20 | 9% |

| D. 11-15 | 0% |

| E. < 11 | 0% |

Ms A scored 17/30 on the MMSE (Folstein et al, 1975), worse than the majority of participants expected, with impairment in orientation (6 points lost), delayed recall (3 points lost), and attention (4 points lost by omitting a single middle letter when spelling “world” backward). Other cognitive screening tests included the clock drawing, which after a permitted self-correction, revealed a normal circle and correct placement and spacing of numbers but incorrect lengths of the hour and minute hands (Figure 1).

On the basis of the information so far, what would you expect the MoCA score to be?

Your Colleagues Who Attended the Banner Alzheimer’s Institute Case Conference Answered as Follows:

| A. 26-30 | 0% |

| B. 21-25 | 12% |

| C. 16-20 | 50% |

| D. 11-15 | 38% |

| E. < 11 | 0% |

Ms A’s MoCA score was lower than the majority of participants expected. Ms A scored 14/30, with impairments in visuospatial/executive function, attention, orientation, language, and delayed recall. Notably, on delayed recall, she was able to recognize 4 of 5 words when provided with multiple choices, suggesting recall difficulties were less likely a reflection of a storage deficit and more likely a retrieval difficulty (Figure 2).

The Montreal Cognitive Assessment (MoCA) has been shown to have a better sensitivity and specificity in detecting subtle cognitive impairments, such as mild cognitive impairment (MCI), compared to the Mini-Mental State Examination (MMSE). Nasreddine et al (2005) found that the MMSE had a sensitivity of 18% to detect MCI, whereas the MoCA detected 90% of MCI subjects. In the mild Alzheimer’s disease group, the MMSE had a sensitivity of 78%, whereas the MoCA detected 100%. Specificity was excellent for both the MMSE and MoCA (100% and 87%, respectively).

On the basis of the information presented thus far, do you think a major neurocognitive disorder is present?

Your Colleagues Who Attended the Banner Alzheimer’s Institute Case Conference Answered as Follows:

| A. Yes | 96% |

| B. No | 0% |

| C. Still not enough information provided | 4% |

After results of the MMSE and MoCA screening tests were provided, most of the participants thought a major neurocognitive disorder was present.

On the basis of the information so far, what underlying etiologic subtype of major neurocognitive disorder is present?

Your Colleagues Who Attended the Banner Alzheimer’s Institute Case Conference Answered as Follows:

| A. Alzheimer’s disease | 48% |

| B. Frontotemporal lobar dementia | 0% |

| C. Dementia with Lewy bodies | 0% |

| D. Vascular disease | 0% |

| E. A mix of ≥ 2 of the above degenerative subtypes (A-D) | 0% |

| F. Adverse effects of medications (polypharmacy) | 0% |

| G. Due to another medical condition | 0% |

| H. Due to multiple etiologies (multifactorial) | 52% |

Almost half of the participants felt that Ms A’s clinical presentation of a gradually worsening impairment in memory, word retrieval, and executive function was most likely due to Alzheimer’s disease. By a slim margin, the majority of participants thought more than 1 etiology was probable. Some participants based that opinion on the patient’s advanced age, while others argued that depression was a contributing factor due to intermittent low energy levels.

THE TREATING PHYSICIAN’ S IMPRESSION

On the basis of the history and clinical presentation as well as the results of the cognitive and physical examination, the treating physician felt that Ms A had a major neurocognitive disorder of mild severity (per DSM-5 criteria). The pattern of symptoms and signs was typical of Alzheimer’s disease, but in this age group, a mixed dementia remained a consideration—specifically, Alzheimer’s combined with vascular disease.

Which of the following evaluations would you schedule next?

Your Colleagues Who Attended the Banner Alzheimer’s Institute Case Conference Answered as Follows:

| A. Standardized neuropsychological evaluation | 4% |

| B. MRI of the brain | 92% |

| C. CT scan of the brain | 0% |

| D. CSF analysis | 0% |

| E. No further testing is necessary; start cholinesterase inhibitor medication for Alzheimer’s disease and observe | 4% |

Almost all of the participants felt that a brain MRI scan should be scheduled next.

On the basis of the evaluation thus far, is brain imaging medically reasonable and appropriate?

Your Colleagues Who Attended the Banner Alzheimer’s Institute Case Conference Answered as Follows:

| A. Yes | 74% |

| B. No | 4% |

| C. Not sure | 13% |

| D. Optional | 9% |

| E. Insufficient information provided | 0% |

The majority of participants felt that brain imaging was reasonable and appropriate. While other participants agreed that the next step in evaluation should be a brain MRI, they questioned whether specific clinical indications exist (appropriate use criteria) to help guide the clinician when reaching a diagnosis of a major neurocognitive disorder. A few participants were unsure whether obtaining a brain scan is a standard of care in this clinical situation.

Would you recommend starting cholinesterase inhibitor therapy, eg, donepezil, before brain MRI results are known?

Your Colleagues Who Attended the Banner Alzheimer’s Institute Case Conference Answered as Follows:

| A. Yes | 25% |

| B. No | 75% |

| C. Not sure | 0% |

The majority of participants thought they should review the additional information from structural imaging before prescribing a cholinesterase inhibitor. Others noted that such therapy is indicated for this patient, as probable Alzheimer’s disease in the mild stage was a reasonable working diagnosis and most likely contributing to Ms A’s cognitive symptomatology. Cholinesterase inhibitors are first-line agents for Alzheimer’s disease. Initial US Food and Drug Administration approval of donepezil was in 1996, with efficacy demonstrated at mild to moderate stages. As part of the initial management plan, the treating physician prescribed donepezil 5 mg and ordered a brain MRI.

Dementia can be classified as probable Alzheimer’s disease when it meets core clinical criteria for all-cause dementia and has characteristics of an insidious or gradual onset of cognitive symptoms over months to years, not sudden over hours or days, with a clear-cut history of worsening reported or observed by others (McKhann et al, 2011). The initial and most prominent cognitive deficits most commonly reflect short-term memory dysfunction, with impairment in learning and recall of recently learned information. There should also be evidence of cognitive dysfunction in at least 1 other cognitive domain, such as reasoning and handling of complex tasks, visuospatial abilities, language functions, or changes in behavior or comportment. Less commonly, nonamnestic presentations occur when the most prominent deficits are in language, visuospatial skills, or executive function.

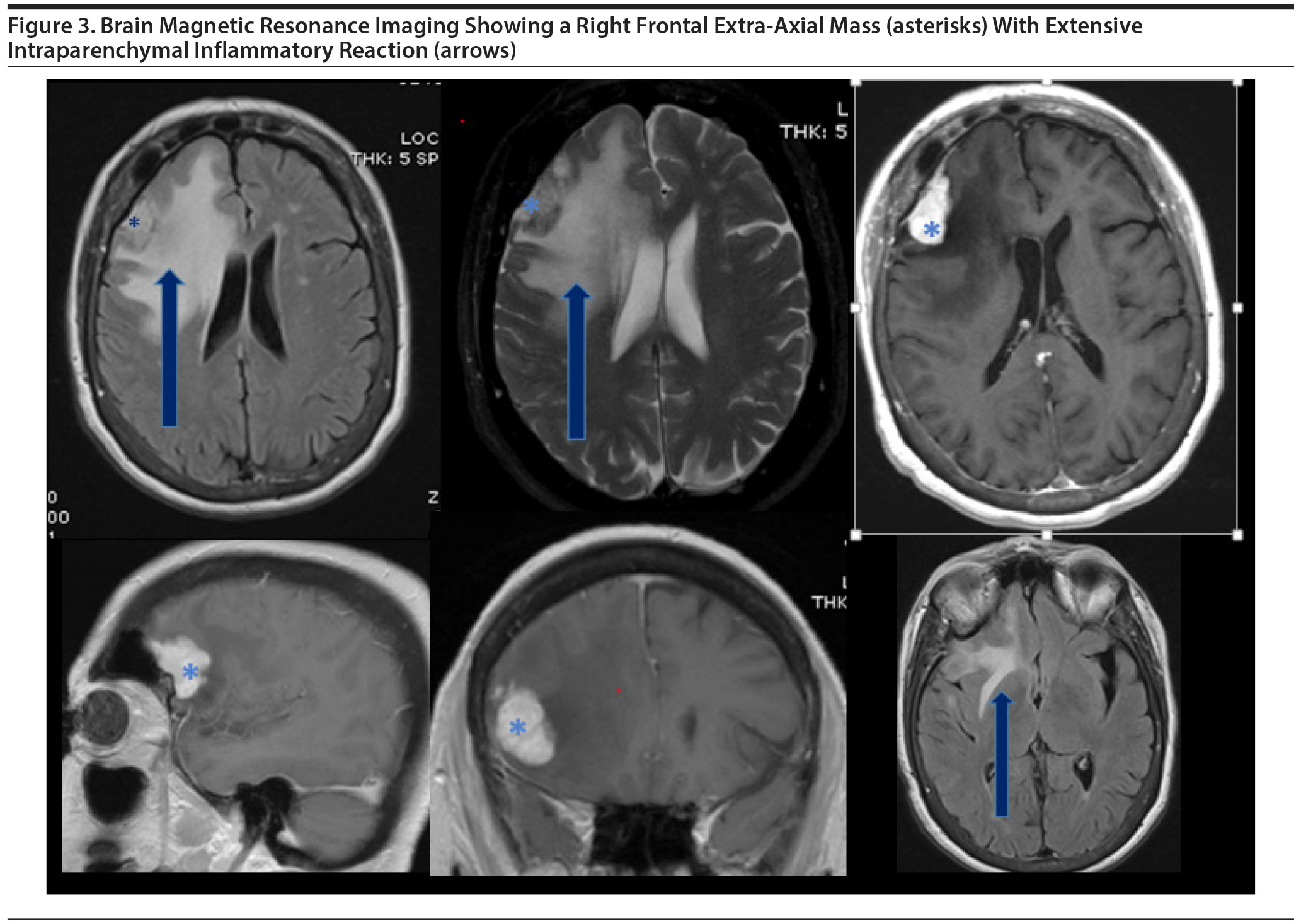

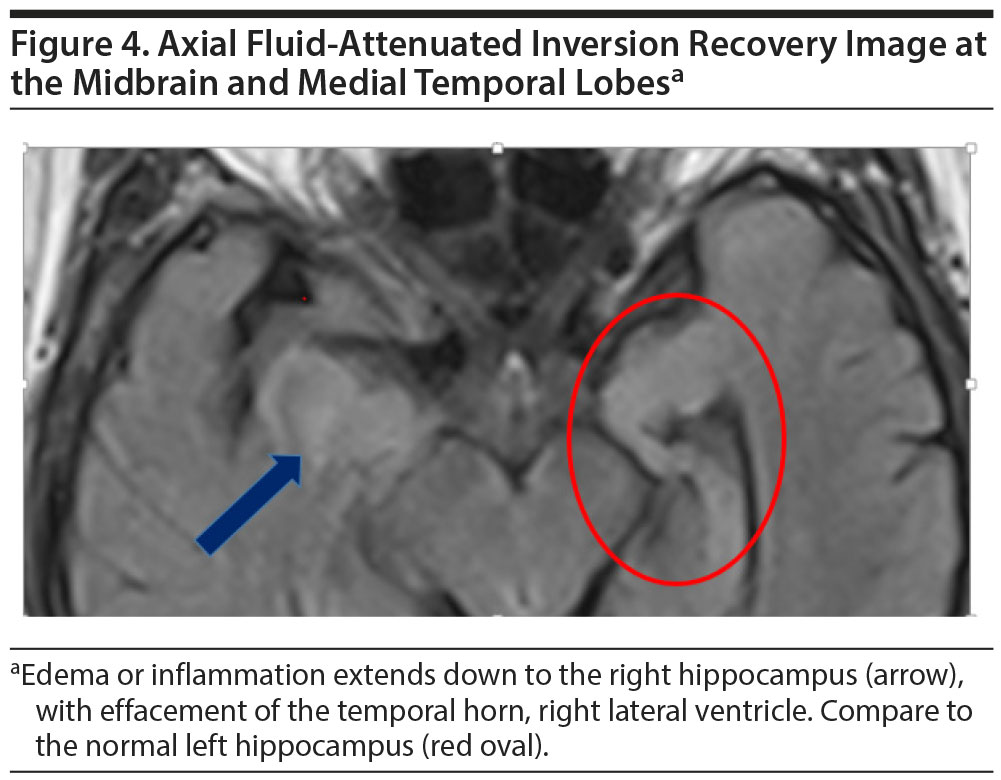

The brain MRI revealed a right frontal extra-axial mass, most consistent with a meningioma (Figure 3), with relatively severe parenchymal inflammatory reaction, which extends inferiorly to include the right hippocampus (Figure 4). A solitary metastasis might have a similar appearance and was in the differential diagnosis.

Click figure to enlarge

On the basis of the information now presented, what is the most likely etiology of the major neurocognitive disorder?

Your Colleagues Who Attended the Banner Alzheimer’s Institute Case Conference Answered as Follows:

| A. Hemispheric brain injury due to the right frontal extra-axial mass and its toxic effect on underlying brain parenchyma | 50% |

| B. Alzheimer’s disease per se (neither the tumor nor the extensive peritumoral edema in the brain is contributing to symptoms) | 0% |

| C. A and B | 46% |

| D. Paraneoplastic syndrome | 4% |

An approximately equal number of participants thought the etiology of Ms A’s condition was due to the toxic effects of the meningioma compared to the number who believed that both Alzheimer’s disease and effects of the meningioma were contributing to symptomatology. Ms A underwent surgical resection of the tumor and recovered well postoperatively. Two months later, the treating physician learned that neither chemotherapy nor radiation was required after surgery.

On the basis of the management of Ms A’s tumor, a clinician would predict the brain biopsy most likely revealed which tumor type?

Your Colleagues Who Attended the Banner Alzheimer’s Institute Case Conference Answered as Follows:

| A. Malignant (invasive) meningioma | 52% |

| B. Benign meningioma | 18% |

| C. Solitary metastasis (has remote history of breast cancer) | 4% |

| D. None of the above | 26% |

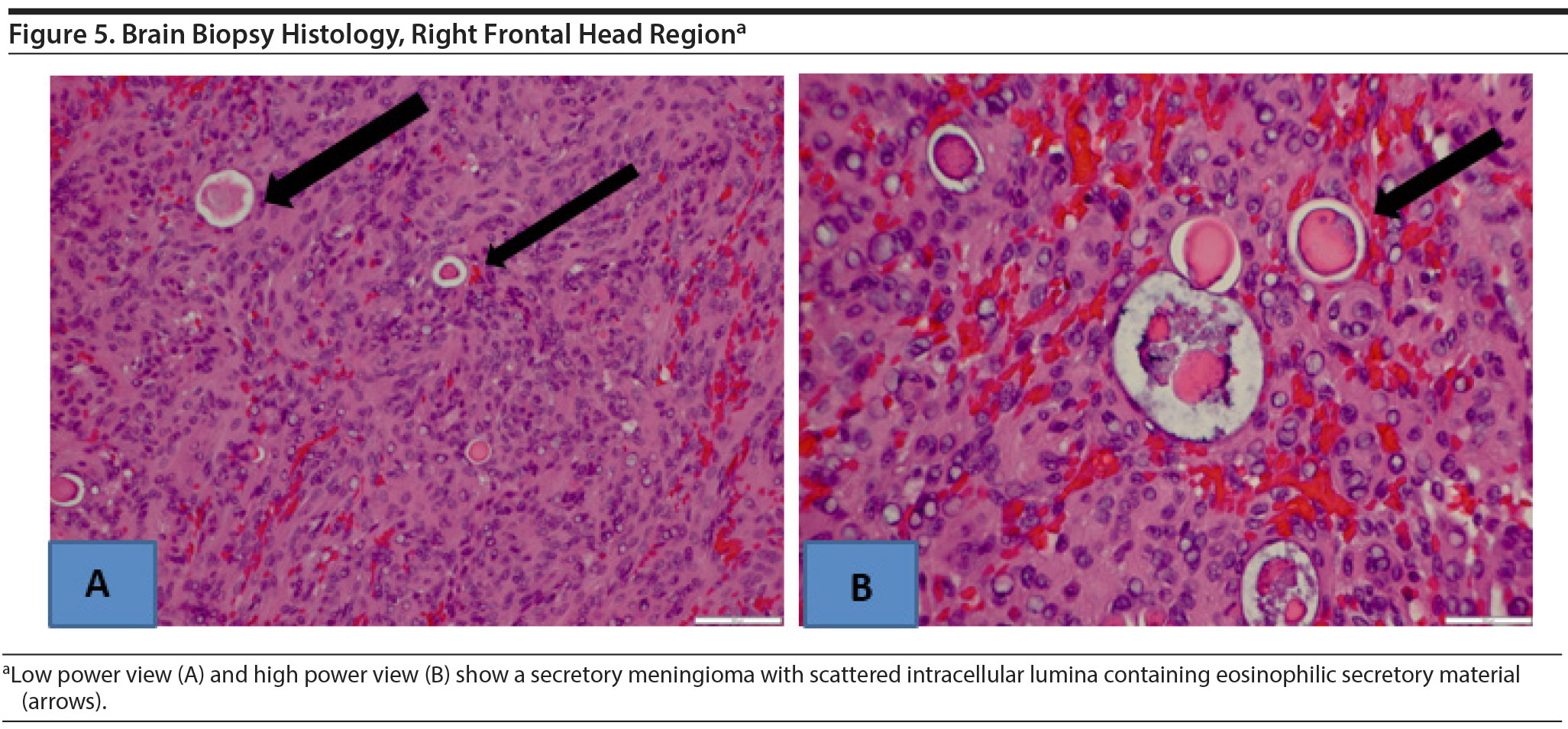

Open biopsy and surgical resection were carried out. A secretory meningioma was found, which was grade 1 by World Health Organization (WHO) criteria. Histology showed predominantly meningiothelial cells with multiple intracellular lumina containing eosinophilic secretory material (Figure 5). No atypical features were seen. A MIB-1 labeling index, a marker of cell proliferation, was low, indicating a benign lesion.

The World Health Organization (WHO) recognizes 15 types of meningioma based on the predominant cell type histologically. WHO currently classifies 3 grades of malignancy: grade 1 is benign, grade 2 is atypical, and grade 3 is malignant. Both the meningiothelial and secretory cell types are among the 9 types classified as grade 1 (Regelsberger et al, 2009; Louis et al, 2016).

With the understanding that Ms A might also have Alzheimer’s disease, the 2011 NIA-AA diagnostic guidelines would classify Alzheimer’s disease in her case as:

Your Colleagues Who Attended the Banner Alzheimer’s Institute Case Conference Answered as Follows:

| A. Possible Alzheimer’s disease | 53% |

| B. Probable Alzheimer’s disease | 38% |

| C. Uncertain Alzheimer’s disease | 9% |

| D. The guidelines are not precise enough to apply a diagnosis | 0% |

Half of the participants chose possible Alzheimer’s disease, based mainly on the etiologically mixed presentation in Ms A’s case. They thought the intraparenchymal edema from the tumor had a substantial impact on cognition but that Alzheimer’s disease was also contributing to symptoms. Other participants felt that the syndrome met the consensus definition for probable Alzheimer’s disease.

A diagnosis of probable Alzheimer’s disease should not be applied when there is evidence for another concurrent, active neurologic disease (McKhann et al, 2011). A diagnosis of possible Alzheimer’s disease is the more precise classification when core clinical criteria are met for Alzheimer’s dementia but there is evidence of concomitant cerebrovascular disease, either with history of stroke temporally related to onset or worsening of cognitive impairment or in the presence of multiple or extensive infarcts or severe white matter hyperintensity burden; or features of dementia with Lewy bodies other than the dementia itself; or evidence for another neurologic disease or medical comorbidity, including medication use, that could have substantial effect on cognition (McKhann et al, 2011). In Ms A’s case, assuming a full remission status after meningioma resection and adequate resolution of the peritumoral edema, continued objective cognitive decline would need to be confirmed to increase the likelihood that Alzheimer’s disease may be a contributing etiology.

DISCUSSION

Alzheimer’s disease may have a typical presentation, but as Ms A’s case illustrates, occasionally another etiology also contributes to cognitive symptomatology. Her clinical dementia syndrome was characterized by insidious onset and then worsening of difficulties predominantly in learning and memory. Mild executive dysfunction was also present. This syndrome is most commonly due to Alzheimer’s disease, yet a significant and potentially life-threatening structural lesion was also identified and thought to be causing or contributing to her memory problems. The peritumoral edema from the right frontal secretory meningioma extended as far inferiorly as the hippocampus and thus increased the likelihood that the lesion was contributing to the cognitive symptoms. A take-home lesson is that a thorough history and unremarkable physical examination are not always sufficient to exclude the possibility of a clinically significant structural abnormality.

The 1994 American Academy of Neurology (AAN) practice parameter for the diagnosis of dementia (Report of the Quality Standards Subcommittee of the AAN, 1994) stated that neuroimaging should be considered in every patient with dementia, but there was no consensus on the need for imaging studies in those older than 60 years without focal signs by history or examination, such as seizures or gait disturbances. A revised AAN practice parameter in 2001 (Knopman et al, 2001) cited additional evidence that about 5% of patients with dementia had a clinically significant structural lesion, yet no features in the history or examination that would have predicted the lesions. Other studies cited in the 2001 report suggested that the decision to order a brain imaging study—based on clinical history and examination alone—was imperfect, with a specificity and sensitivity of approximately 90%. The AAN recommended that structural imaging was appropriate (Knopman et al, 2001). Although the parameter was a practice guideline, not a standard of care, brain imaging has become an essential component of the comprehensive evaluation of a patient whose presentation meets criteria for a major neurocognitive disorder.

Etiologically mixed presentations of dementia, meeting core clinical criteria for Alzheimer’s disease but related also to a symptomatic brain lesion, are uncommon. In Ms A’s case, at age 87 years, the finding of a secretory meningioma is even rarer. A much more frequent consideration in the assessment of persons in Ms A’s age group is mixed dementia, which is characterized by the hallmark abnormalities of more than 1 type of brain degeneration causing the dementia and confirmed by more than 1 degenerative pathology found at autopsy. The most common type of mixed dementia is Alzheimer’s combined with vascular dementia, followed by Alzheimer’s with dementia with Lewy bodies (DLB) and Alzheimer’s with vascular dementia and DLB. Vascular dementia with DLB is much less common. Mixed dementia is more frequent than previously recognized by dementia specialists. About half of people whose symptoms of dementia start when elderly will have pathologic evidence of more than 1 cause of dementia (Alzheimer’s Association, 2017). Recent studies also show that the likelihood of having mixed dementia increases with age and is highest in the oldest-old: people aged 85 or older (Schneider et al, 2007).

Physicians during medical school training are often taught the adage, “When you hear hoof beats, think of horses, not zebras.” The rationale is to warn against the natural bias of younger physicians to more easily recall rare and exotic conditions (Sotos, 2006). Experienced clinicians understand, however, that while giving the more common conditions their due consideration, uncommon diagnoses should be kept in the differential diagnosis until there is conclusive evidence that rules them out (Harvey and Bordley, 1979). In evaluating a case such as Ms A’s , in which more than one etiology most likely contributed to symptoms of dementia, the astute diagnostician perhaps would best listen for the hoof beats of both horses and zebras.

Clinical Points

- In the evaluation of a patient presenting with mild dementia, a thorough history and unremarkable physical examination are not always sufficient to exclude the possibility of a clinically significant structural abnormality.

- When encountering a patient meeting clinical criteria for a major neurocognitive disorder, dementia specialists consider brain imaging an essential component of the comprehensive evaluation; at a primary care level, adoption of a similar approach may be prudent.

FUNDING/SUPPORT

None.

drug names

Albuterol (Proair, Proventil, and others), donepezil (Aricept and others), duloxetine (Cymbalta and others), fluticasone (Flovent and others), pravastatin (Pravachol and others), ranitidine (Zantac and others), tolterodine (Detrol and others), zoledronic acid (Reclast, Zometa, and others).

Disclosure of off-label usage

The authors have determined that, to the best of their knowledge, no investigational information about pharmaceutical agents that is outside US Food and Drug Administration-approved labeling has been presented in this article.

Financial Disclosure

Dr Anna D. Burke is a consultant for Eli Lilly and a member of the speakers/advisory boards for Eli Lilly and Rockpointe. Drs Weidman, Eschbacher, Copeland, and William J. Burke and Ms Grigaitis-Reyes have no personal affiliations or financial relationships with any commercial interest to disclose relative to the article.

Case Conference

The Banner Alzheimer’s Institute Case Conference is a weekly event in which physicians and staff discuss challenging teaching cases of patients seen at the Institute’s Stead Family Memory Clinic. These conferences are attended by a multidisciplinary group that includes Banner Alzheimer’s Institute dementia specialists, community physicians (internal medicine, family medicine, and radiology), physician assistants, social workers, nurses, medical students, residents, and fellows. The Banner Alzheimer’s Institute located in Phoenix, Arizona, has an unusually ambitious mission: to end Alzheimer’s disease without losing a generation, set a new standard of care for patients and families, and forge a model of collaboration in biomedical research. The Institute provides high-level care and treatment for patients affected by Alzheimer’s disease, dementia, and related disorders. In addition, the Institute offers extensive support services for families and many unique and rewarding research opportunities.

Disclaimer

The opinions expressed are those of the authors, not of Banner Health or Physicians Postgraduate Press., Inc.

Find more articles on this and other psychiatry and CNS topics:

The Journal of Clinical Psychiatry

The Primary Care Companion for CNS Disorders

References

Alzheimer’s Association. Alzheimer’s disease facts and figures. Alzheimers Dement. 2017;13:325-373.

American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders. Fifth Edition. Arlington, VA: American Psychiatric Association; 2013.

Folstein MF, Folstein SE, McHugh PR. “Mini-mental state”: a practical method for grading the cognitive state of patients for the clinician. J Psychiatr Res. 1975;12(3):189-198. PubMed CrossRef

Harvey AM, Bordley J. Differential Diagnosis: the Interpretation of Clinical Evidence. Philadelphia, PA: Saunders; 1979.

Knopman DS, DeKosky ST, Cummings JL, et al. Practice parameter: diagnosis of dementia (an evidence-based review): Report of the Quality Standards Subcommittee of the American Academy of Neurology. Neurology. 2001;56(9):1143-1153. PubMed CrossRef

Louis DN, Perry A, Reifenberger G, et al. The 2016 World Health Organization Classification of Tumors of the Central Nervous System: a summary. Acta Neuropathol. 2016;131(6):803-820. PubMed CrossRef

McKhann GM, Knopman DS, Chertkow H, et al. The diagnosis of dementia due to Alzheimer’s disease: recommendations from the National Institute on Aging-Alzheimer’s Association workgroups on diagnostic guidelines for Alzheimer’s disease. Alzheimers Dement. 2011;7(3):263-269. PubMed CrossRef

Nasreddine ZS, Phillips NA, Bédirian V, et al. The Montreal Cognitive Assessment, MoCA: a brief screening tool for mild cognitive impairment. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2005;53(4):695-699. PubMed CrossRef

Practice Parameter for Diagnosis and Evaluation of Dementia (summary statement). Report of the Quality Standards Subcommittee of the American Academy of Neurology. Neurology. 1994;44(11):2203-2206. PubMed CrossRef

Regelsberger J, Hagel C, Emami P, et al. Secretory meningiomas: a benign subgroup causing life-threatening complications. Neuro-oncol. 2009;11(6):819-824. PubMed CrossRef

Schneider JA, Arvanitakis Z, Bang W, et al. Mixed brain pathologies account for most dementia cases in community-dwelling older persons. Neurology. 2007;69(24):2197-2204. PubMed CrossRef

Sotos JG. Zebra Cards: An Aid to Obscure Diagnosis. Mt Vernon, VA: Mt Vernon Book Systems; 2006.

Enjoy this premium PDF as part of your membership benefits!