Find more articles on this and other psychiatry and CNS topics:

The Journal of Clinical Psychiatry

The Primary Care Companion for CNS Disorders

CASE CONFERENCE

The Banner Alzheimer’s Institute Case Conference is a weekly event in which physicians and staff discuss challenging and/or teaching cases of patients seen at the Institute’s Memory Disorders Clinic. These conferences are attended by a multidisciplinary group that includes Banner Alzheimer’s Institute dementia specialists, community physicians (internal medicine, family medicine, and radiology), physician assistants, social workers, nurses, medical students, residents, and fellows.

BANNER ALZHEIMER’ S INSTITUTE

The Banner Alzheimer’s Institute located in Phoenix, Arizona, has an unusually ambitious mission: to end Alzheimer’s disease without losing a generation, set a new standard of care for patients and families, and forge a model of collaboration in biomedical research. The Institute provides high-level care and treatment for patients affected by Alzheimer’s disease, dementia, and related disorders. In addition, the Institute offers extensive support services for families and many unique and rewarding research opportunities.

Received: September 12, 2011; accepted September 12, 2011.

Published online: October 27, 2011.

Prim Care Companion CNS Disord 2011;13(5):doi:10.4088/PCC.11alz01292

© Copyright 2011 Physicians Postgraduate Press, Inc.

AUTHORS

Roy Yaari, MD, MAS, a neurologist, is associate director of the Memory Disorders Clinic of Banner Alzheimer’s Institute and a clinical professor of neurology at the College of Medicine, University of Arizona, Tucson.

Helle Brand, PA, is a physician assistant at the Memory Disorders Clinic of Banner Alzheimer’s Institute.

James Seward, PhD, ABPP, is a clinical neuropsychologist at Banner Alzheimer’s Institute.

Anna Burke, MD, is a geriatric psychiatrist and dementia specialist at the Memory Disorders Clinic of Banner Alzheimer’s Institute.

Adam S. Fleisher, MD, MAS, is associate director of Brain Imaging at the Banner Alzheimer’s Institute, a neurologist at the Institute’s Memory Disorders Clinic, and an associate professor in the Department of Neurosciences at the University of California, San Diego.

Jan Dougherty, RN, MS, is director of Family and Community Services at Banner Alzheimer’s Institute.

Pierre N. Tariot, MD, a geriatric psychiatrist, is director of Banner Alzheimer’s Institute and a research professor of psychiatry at the College of Medicine, University of Arizona, Tucson.

Corresponding author: Roy Yaari, MD, MAS, 901 E Willetta St, Phoenix, AZ 85006 ([email protected]).

Original material is selected for credit designation based on an assessment of the educational needs of CME participants, with the purpose of providing readers with a curriculum of CME activities on a variety of topics from volume to volume. This special series of case reports about dementia was deemed valuable for educational purposes by the Publisher, Editor in Chief, and CME Institute Staff. Activities are planned using a process that links identified needs with desired results.

To obtain credit, read the material and go to PSYCHIATRIST.COM to complete the Posttest and Evaluation online.

This case conference was prepared entirely by the authors with no external support.

CME Objective

After studying this case, you should be able to:

- Diagnose a geriatric patient whose family reports changes in behavior (such as rudeness and overexercising), problems handling money, and difficulty naming objects correctly.

Accreditation Statement

The CME Institute of Physicians Postgraduate Press, Inc., is accredited by the Accreditation Council for Continuing Medical Education to provide continuing medical education for physicians.

Credit Designation

The CME Institute of Physicians Postgraduate Press, Inc., designates this journal-based CME activity for a maximum of 1.0 AMA PRA Category 1 Creditâ„¢. Physicians should claim only the credit commensurate with the extent of their participation in the activity.

Note: The American Academy of Physician Assistants (AAPA) accepts certificates of participation for educational activities certified for AMA PRA Category 1 Creditâ„¢ from organizations accredited by ACCME or a recognized state medical society. Physician assistants may receive a maximum of 1.0 hour of Category I credit for completing this program.

Date of Original Release/Review

This educational activity is eligible for AMA PRA Category 1 Credit through October 31, 2014. The latest review of this material was October 2011.

Financial Disclosure

All individuals in a position to influence the content of this activity were asked to complete a statement regarding all relevant personal financial relationships between themselves or their spouse/partner and any commercial interest. The CME Institute has resolved any conflicts of interest that were identified. In the past year, Larry Culpepper, MD, MPH, Editor in Chief, has been a consultant for AstraZeneca, Labopharm, Pfizer, and Trovis; has been a member of the speakers/advisory board for Merck; and has held stock in Labopharm. No member of the CME Institute staff reported any relevant personal financial relationships. Faculty financial disclosure appears at the end of the article.

HISTORY OF PRESENT ILLNESS

Mr A, a 70-year-old man, presented to the Banner Alzheimer’s Institute for a cognitive evaluation. He presented with his wife and son, who both provided the clinical history. Mr A was first noted by his family to have cognitive changes approximately 18 months prior to his initial presentation at the Institute. At that time, he began to forget names of golf buddies and restaurants. Soon after, Mr A exhibited personality changes such that he displayed a lack of empathy for others and became “self-centered.” He became “fidgety,” with an increase in energy and pacing back and forth. He exercised excessively, for example, taking 4 bike rides and 8 walks in a day. The family reported that Mr A could not sit still. He also began to laugh inappropriately. Mr A performed all of his instrumental and personal activities of daily living without any difficulty. Mr A was evaluated by a community neurologist who diagnosed him with mild cognitive impairment. Soon thereafter, Mr A began to have difficulties with activities of daily living such as handling cash. At a subsequent clinic visit with his community neurologist, the diagnosis was changed to Alzheimer’s disease dementia.

Donepezil was initiated without obvious improvement, and Mr A experienced a significant diminution of his sense of taste and smell. Due to this side effect, donepezil was discontinued after 3 months. Memantine was then initiated without obvious cognitive benefit, but it also reduced his sense of taste and smell and was discontinued. Rivastigmine transdermal patch was initiated and stopped due to the same side effects. Mr A was subsequently placed on a low dose of galantamine (4 mg) for 4 months without side effects. His community neurologist also initiated citalopram to help treat compulsive behaviors, with no noticeable improvement in behavior.

At the time of Mr A’s first evaluation at the Institute, the family noted further decline in cognition. He had trouble knowing where previously familiar stores and restaurants were located. He had become “rude.” His family noted that Mr A walked around and paced, laughed after everything he said, and had terrible anxiety on the golf course. Mr A was misnaming objects. For example, he was unable to name a paperclip or a yardstick. Mr A called a cane a steering wheel. He was not repetitive with questions or stories. The family stated that Mr A was able to track appointments, but he was overwhelmed with paperwork and misplaced items. Mr A was oriented to time and to current events. He was noted to be anxious but not depressed. Mr A would have significant outbursts of anger but was not physically aggressive. Mr A was independent in personal activities of daily living, and his weight was stable. He had trouble managing cash, and his wife had begun to oversee finances. Mr A continued to drive, but his wife was concerned about safety due to aggression. Mr A was administering his own medications independently without errors. Mr A recently had given up golf, which was difficult for him.

PAST MEDICAL HISTORY

Mr A had a history of hypercholesterolemia. He had surgeries for rotator cuff repair and a detached retina in both eyes at approximately 50 years of age. A vitrectomy in his left eye was not successful, and he continued to have “wiggly vision” in that eye.

ALLERGIES

Mr A had no known drug allergies. He experienced anosmia and ageusia with donepezil, memantine, and rivastigmine.

MEDICATIONS

Mr A was taking simvastatin, citalopram 40 mg/d, and galantamine 4 mg/d.

SOCIAL HISTORY

Mr A had 12 years of education and worked as a salesman. He had 3 children, all of whom lived locally. He lived with his wife. Mr A had no significant history of alcohol abuse, and he drank 1-2 alcoholic beverages per day. He quit smoking at the age of 35 years.

FAMILY HISTORY

Mr A’s mother was diagnosed with Alzheimer’s disease dementia and died at the age of 84 years. His sister, who is 2 years older, developed symptoms at the age of 62 years and was also diagnosed with Alzheimer’s disease.

PHYSICAL EXAMINATION

Mr A’s vital signs were blood pressure: 128/76 mm Hg, pulse: 76 bpm, height: 71 inches, and weight: 209.4 lb. Mr A’s general physical examination was unremarkable except for bilateral surgical pupils.

NEUROLOGIC EXAMINATION

Mr A’s neurologic examination was unremarkable except for broken smooth eye pursuits and positive glabellar and snout frontal release signs. Deep tendon reflexes were quite brisk but symmetric throughout.

Different dementias may be associated with various physical examination findings. However, most often the physical examination is normal in the early stages. Some subtle general findings can include frontal release signs such as a positive snout, glabellar, or palmomental reflex (Links et al, 2010).

LABORATORIES/RADIOLOGY

Mr A had undergone a full workup by his community neurologist. His laboratory test results, including a complete blood count, comprehensive metabolic panel, and vitamin B12 and thyroid-stimulating hormone levels, were unremarkable. A magnetic resonance image (MRI) of the brain without contrast was normal.

Guidelines for a routine dementia workup include a complete blood count, comprehensive metabolic panel, vitamin B12 test, thyroid-stimulating hormone test, and structural brain imaging with either MRI or computed tomography (Knopman et al, 2001). In this case, the basic workup to rule out nondementia etiology of cognitive impairment was completed.

The DSM-IV defines dementia as multiple cognitive deficits that include memory impairment and at least 1 of the following cognitive disturbances: aphasia, apraxia, agnosia, or a disturbance in executive functioning. The cognitive deficits must be sufficiently severe to cause impairment in social or occupational functioning and must represent a decline from a previously higher level of functioning. A diagnosis of dementia should not be made if the cognitive deficits occur exclusively during the course of a delirium (American Psychiatric Association, 2000).

Mild cognitive impairment refers to cognitive impairment that does not meet the criteria for normal aging or dementia because the cognitive impairment does not impair activities of daily living. Several criteria for, and subtypes of, mild cognitive impairment have been proposed (Voisin et al, 2003). Originally, mild cognitive impairment emphasized memory impairment as a precursor state for Alzheimer’s disease (Petersen et al, 1999). It then became apparent that mild cognitive impairment is a heterogeneous entity that affects other cognitive domains and includes the prodromal stages of other dementias. The diagnostic criteria for mild cognitive impairment are not exact and require subjectivity in determining whether a cognitive impairment is present or what constitutes impairment in activities of daily living.

Based on the clinical history alone, do you think

Your colleagues who attended the Banner Alzheimer’s Institute Case Conference answered as follows:

| A. He meets criteria for dementia | 100% |

| B. He is likely cognitively normal | 0% |

| C. He possibly has mild cognitive impairment | 0% |

| D. His cognitive issues are likely due to an underlying psychiatric disorder | 0% |

Of the conference attendees, 100% believed that the clinical history was consistent with a dementia given the presence of cognitive impairment that affected functioning in finances, golf, and possibly driving and represented a decline from a previously higher level of functioning.

Clinical Note

The most common side effects of cholinesterase inhibitors (donepezil, rivastigmine, and galantamine) include cholinergic side effects of diarrhea, nausea, vomiting, and bradycardia (can be symptomatic with syncope) (Farlow et al, 2008; Gill et al, 2009). The tolerability of memantine does not differ from placebo, with potential side effects of constipation, dizziness, confusion, and headache (Farlow et al, 2008). The reversible ageusia and anosmia reported by Mr A are not reported side effects with these medications.

Based on the clinical history alone, which do you believe is most accurate?

Your colleagues who attended the Banner Alzheimer’s Institute Case Conference answered as follows:

| A. He most likely does not have a progressive neurodegenerative condition | 0% |

| B. His symptoms are most likely due to depression and anxiety | 0% |

| C. His symptoms are more consistent with a FTD | 40% |

| D. His symptoms are more consistent with Alzheimer’s disease | 27% |

| E. He most likely has dementia, not otherwise specified | 33% |

All attendees were in agreement that Mr A had a progressive neurodegenerative dementia as evident by the workup thus far. On the basis of the group responses, there remained uncertainty regarding the etiology of the dementia, and further workup would be required. Those who chose FTD argued that there were significant early behavioral changes and language disturbances that are symptoms more consistent with FTD. Those who chose Alzheimer’s disease stated that memory complaints, specifically in terms of names and places, were Mr A’s first presenting feature and more consistent with Alzheimer’s disease, especially coupled with the family history. Many conference attendees could not commit to either FTD or Alzheimer’s disease given the information obtained thus far.

A MMSE (Folstein et al, 1975) score generally correlates with disease severity. Scores ≤ 9 can indicate severe dementia, between 10-20 can indicate moderate dementia, and > 20 can indicate mild dementia (Mungas, 1991). MMSE scores vary by age and education. MMSE scores and age have an inverse relationship, with scores ranging from a median of 29 for people aged 18 to 24 years, to a median of 25 for individuals over the age of 80. MMSE scores and years of education have a direct relationship. Those with 0 to 4 years of education have a median MMSE score of 22, whereas those with at least 9 years of education have a median MMSE score of 29 (Crum et al, 1993).

Based on the clinical history alone, what would you expect his MMSE score to be?

Your colleagues who attended the Banner Alzheimer’s Institute Case Conference answered as follows:

| A. 28-30 | 0% |

| B. 25-27 | 18% |

| C. 22-24 | 59% |

| D. 19-21 | 23% |

| E. 15-18 | 0% |

Mr A scored 25 out of 30 points on the MMSE. He missed 1 point on orientation, 3 points on delayed recall, and 1 point on the written sentence. Given that Mr A was having difficulty recalling names of people and places that he was familiar with, coupled with the inability to handle cash, 82% of conference attendees expected a slightly lower score on this test. Mr A’s pentagon copy (Figure 1) and written sentence (Figure 2) from the MMSE are shown. The pentagon copy was correct, but Mr A missed a point for the sentence.

The MoCA (Nasreddine et al, 2005) is a 30-point test that assesses several cognitive domains. Because it is more challenging than the MMSE, it has greater sensitivity for mild cognitive impairment and early stages of dementia. With a cutoff score < 26, the sensitivity for detecting mild cognitive impairment (N = 94) was found to be 90% and the specificity 87%.

Based on the clinical history alone, what would you expect his MoCA score to be?

Your colleagues who attended the Banner Alzheimer’s Institute Case Conference answered as follows:

| A. 28-30 | 0% |

| B. 25-27 | 0% |

| C. 22-24 | 18% |

| D. 19-21 | 53% |

| E. 15-18 | 29% |

| F. Below 15 | 0% |

Mr A scored 14 out of 30 points on the MoCA, a lower score than was expected given the clinical history, and the majority of respondents had assumed he would score above 19 (Figure 3). This result illustrates the apparently greater sensitivity of the MoCA in early stages of dementia as compared to the MMSE.

In the Category Retrieval Test, the examiner asks the patient to name as many animals as possible in 1 minute. Performance on this measure is influenced by age; unimpaired people in their 60s should name about 18 animals, whereas people in their 80s should name about 15 (Mitrushina et al, 2005). There is no hard-and-fast cutoff for impairment. However, patients who name 4 or more animals less than expected raise concerns. Note that bilingual individuals are at a disadvantage on this test and in other measures of verbal fluency (Gollan et al, 2002).

Based on the clinical history alone, what would you expect his Category Retrieval Test score to be?

Your colleagues who attended the Banner Alzheimer’s Institute Case Conference answered as follows:

| A. 0-5 | 0% |

| B. 6-10 | 76% |

| C. 11-15 | 18% |

| D. 16-20 | 6% |

| E. 21-25 | 0% |

Mr A’s Category Retrieval Test score was 4, with 1 error. The results are included in Figure 4.

At this time, what tests, if any, would you like to order?

Your colleagues who attended the Banner Alzheimer’s Institute Case Conference answered as follows:

| A. No further tests are indicated at this time | 11% |

| B. Neuropsychological testing | 0% |

| C. FDG-PET scan | 5% |

| D. Request outside MRI for review | 16% |

| E. B and C | 52% |

| F. B and D | 16% |

Although the majority of respondents chose both an FDG-PET scan and formal neuropsychological testing, the treating physician chose to order just the FDG-PET scan. The treating physician reasoned that if the FDG-PET scan resulted in an unequivocal diagnosis of either FTD or Alzheimer’s disease, then this would be sufficient to give a conclusive diagnosis. If the FDG-PET result was ambiguous, then neuropsychological testing would be ordered.

Given the issues with driving, what should be done at this time, if anything?

Your colleagues who attended the Banner Alzheimer’s Institute Case Conference answered as follows:

| A. No need to discuss driving at this time | 0% |

| B. Driving must stop—report to Department of Motor Vehicles if patient refuses | 7% |

| C. Recommend formal driving evaluation | 93% |

| D. Restrict driving to within 5 miles from home; family to closely monitor | 0% |

Of the conference attendees, 7% believed that driving must stop given the diagnosis of dementia and the family reporting that the patient was driving “aggressively.” Because there had been no accidents, citations, or reports of not following the “rules” of driving and no confusion in intersections, 93% believed that a formal on-road driving safety evaluation was indicated. The treating physician believed that driving should be stopped on the basis of the report from the family. Of note, the history regarding Mr A’s driving ability was taken from the family while the patient was not present, as they could not discuss this issue in front of him. Had Mr A known that the family reported aggressive driving to the doctor, he would have been livid and directed his anger toward the family. The treating physician told Mr A that, on the basis of the results of cognitive testing, there were concerns regarding driving ability and that a formal driving safety evaluation was required should he wish to continue to drive.

THE TREATING PHYSICIAN’ S IMPRESSION

Mr A, a 70-year-old man who presented for a cognitive evaluation, had a clinical history and cognitive findings consistent with dementia. Given the predominance of behavioral changes, the clinical history suggested FTD. Alzheimer’s disease was also a consideration. Further workup with an FDG-PET can help distinguish between these 2 types of dementia.

THE TREATING PHYSICIAN’ S PLAN

- Order FDG-PET scan of the brain.

- Increase galantamine to 8 mg/d (with extended-release formulation).

- Continue citalopram 40 mg/d for now. The family reports no benefit with this medication. There will be a low threshold to change to a different medication.

- The patient’s family has been referred to the caregiver class and the planning for the future class.

- The patient’s family will be scheduled to meet with one of our nurse specialists to help understand the patient’s condition and formulate a nonpharmacologic treatment plan in reacting to his abnormal behaviors.

- Although the patient may not have FTD, the FTD dementia support group may be beneficial for the patient’s family as he displays significant behavioral changes.

- We discussed the issue of driving. At this time, I do not feel that the patient should be driving unless he passes a formal driving evaluation. I recommended that the patient have a formal on-road driving safety evaluation.

- The patient will follow up with me after the FDG-PET scan has been completed.

FDG-PET Results

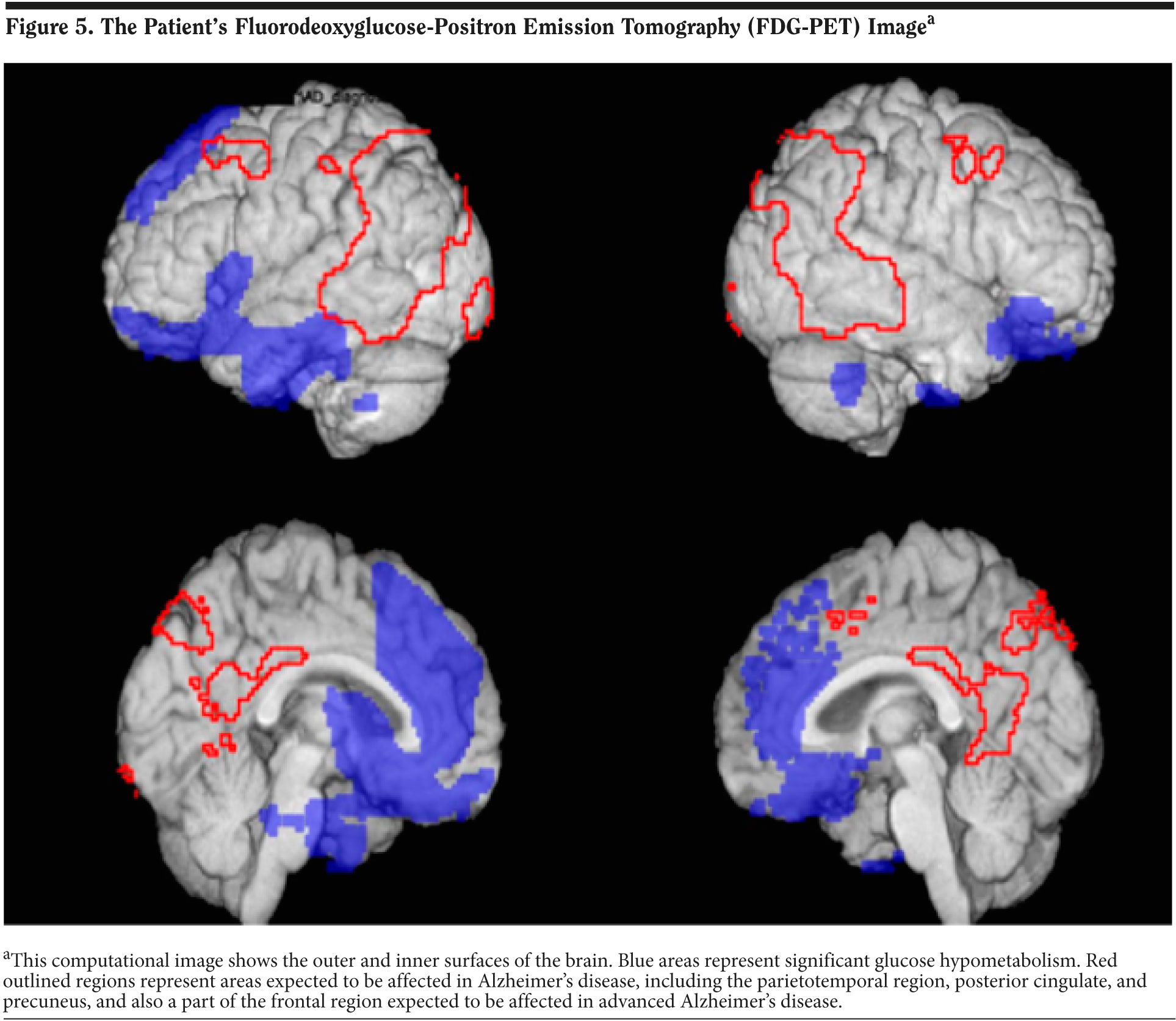

The results of Mr A’s FDG-PET scan are shown in Figure 5. FDG-PET scans measure cerebral metabolic rate of glucose metabolism. This computational image shows the outer and inner surfaces of the brain. Blue areas represent significant glucose hypometabolism. Red outlined regions represent areas expected to be affected in Alzheimer’s disease, including the parietotemporal region, posterior cingulate, and precuneus, and also a part of the frontal region expected to be affected in advanced Alzheimer’s disease. The results show significant hypometabolism in the bilateral frontal and temporal regions consistent with FTD. The FDG-PET results and diagnosis of FTD were given to the patient’s wife over the phone by the treating physician.

DISCUSSION

Frontotemporal dementia is a clinical syndrome of a group of neuropathologically heterogeneous disorders associated with degeneration of the frontal and temporal lobes. Frontotemporal dementia generally presents with progressive changes in personality and social behavior but also can include prominent disturbances in language and executive function. Some patients also develop motor-neuron disease (MND), a syndrome designated FTD-MND. In these cases, patients can have progressive muscular atrophy with fasciculations. Bulbar muscles can be affected (leading to dysarthria and dysphagia) as well as extremity muscles. The age at onset is generally younger than with Alzheimer’s disease, affecting people in their 50s and 60s. The median duration of FTD from onset to death is 6 to 8 years (range, 2-20 years) with equivalent survival across FTD subgroups (Hodges et al, 2003; Snowden et al, 1996). FTD-MND is associated with a median survival of only 3 years (Hodges et al, 2003; Neary et al, 1990).

There are 3 main categories of the clinical FTD syndrome: behavioral variant, nonfluent primary progressive aphasia, and semantic dementia. There is, however, considerable overlap between these categories, and it can be difficult to clearly classify a patient in a given category. The behavioral variant is the most common presentation of FTD. There are personality changes, lack of insight or social awareness, lack of empathy, and stereotyped behaviors. Cognitive testing may be relatively intact in the early stages of FTD. The progressive nonfluent aphasia variant manifests with impairment of expressive language and gradually worsening spontaneous speech in the context of generally preserved word comprehension. Ultimately, comprehension can be affected as well. The semantic variant manifests with impaired comprehension and semantic paraphasias with normal fluency.

Characteristics of FTD include a sex distribution of approximately 50:50 for men and women, respectively; an age of onset of 45 to 65 years (range, 21-85 years); a duration of illness of 6 to 8 years (3 years in FTD-MND); and a family history in 40% to 50% of patients (Neary et al, 2005). The presenting problem is typically behavioral change, and cognitive features include executive deficits and changes in speech and language. Neurologic signs are commonly absent in the early stage, parkinsonism is present in the late stages, and MND is present in a small proportion of patients. Abnormalities in frontotemporal lobes are present, especially on functional imaging (Neary et al, 2005).

Follow-Up

Mr A returned to the clinic 5 weeks later for follow-up. He continues to have socially inappropriate behaviors such as making funny faces to kids and walking up to people he does not know, as well as instances of flatulence and eructation in public with inappropriate laughter. He has outbursts of anger with minimal provocation. The increase in galantamine dose has had no obvious benefits. Since the last visit, Mr A’s primary care physician discontinued the citalopram and initiated paroxetine 20 mg without benefit. Mr A has not yet had a formal driving evaluation.

Should the cholinesterase inhibitor be adjusted?

Your colleagues who attended the Banner Alzheimer’s Institute Case Conference answered as follows:

| A. Discontinue galantamine and stop treatment with cholinesterase inhibitors | 20% |

| B. No need to change the dose of galantamine at this time | 0% |

| C. Increase galantamine; the patient is on a low dose | 80% |

| D. Retry rivastigmine or donepezil | 0% |

Of the conference attendees, 80% believed that the galantamine should be increased, and 20% recommended discontinuation of galantamine. The treating physician chose to stop galantamine because cholinesterase inhibitors have not been shown in case reports to improve cognition in FTD and can sometimes worsen behaviors (Kertesz et al, 2008; Mendez et al, 2007; Moretti et al, 2004); however, no controlled trials have been conducted to guide practice. (Had Mr A been diagnosed with Alzheimer’s disease, the treating physician would have increased the galantamine despite lack of obvious benefit.)

There are currently no US Food and Drug-approved medications for treatment of FTD. Pharmacologic treatment of FTD is limited and targets the symptoms. Although selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors are often used to manage behavioral symptoms, their reported effectiveness is variable (Mendez, 2009). Other medications that can be used are atypical antipsychotics, antiepileptic drugs, and memantine.

Should the antidepressant be adjusted?

Your colleagues who attended the Banner Alzheimer’s Institute Case Conference answered as follows:

| A. Increase dose of paroxetine | 44% |

| B. Switch paroxetine to another agent | 56% |

| C. Add a second antidepressant to the paroxetine | 0% |

| D. No change to paroxetine dose; he has not been on this medication long enough to assess | 0% |

Of the conference attendees, 56% suggested switching paroxetine to another agent and 44% suggested increasing the dose. Given the anticholinergic properties and lack of reported efficacy in this patient, the treating physician discontinued the paroxetine and initiated divalproex sodium extended release 250 mg/d.

The patient returned 2 months later for follow-up. The family noted that Mr A was calmer since starting the divalproex sodium extended release, but he had gained 10 lb. Mr A continues to have gradual worsening language difficulties. The divalproex sodium extended release was increased to 500 mg/d in an attempt to gain further behavior benefit.

Mr A passed a formal on-road driving safety evaluation performed by a local company. The family continues to state that he is a driving hazard and is a danger due to impulsive decisions and aggressive behavior. Mr A was therefore instructed to stop driving. As expected, he resisted, but he eventually acquiesced and reluctantly agreed to discontinue driving.

Mr A returned 3 months later for follow-up. His language expression and comprehension have continued to worsen. He continues to be significantly disinhibited, and personal hygiene has declined. He continues to be compulsive with exercise. His family utilizes a GPS tracking device to monitor his whereabouts when mountain biking and jogging. He has not gotten lost. Although he was initially angry regarding driving cessation, Mr A seldom brings up the topic. The increase in divalproex sodium extended release had no further benefit, and the dose was reduced back to 250 mg/d. We can consider initiating an antitypical antipsychotic such as quetiapine if behavioral symptoms significantly worsen in the future.

Disclosure of off-label usage

The authors have determined that, to the best of their knowledge, citalopram, divalproex, donepezil, galantamine, memantine, paroxetine, quetiapine, rivastigmine, and simvastatin are not approved by the US Food and Drug Administration for the treatment of frontotemporal dementia.

FINANCIAL DISCLOSURE

Dr Yaari is a consultant for Amedisys Home Health. Dr Tariot is a consultant for Acadia, AC Immune, Allergan, Eisai, Epix, Forest, Genentech, MedAvante, Memory Pharmaceuticals, Myriad, Novartis, Sanofi-Aventis, Schering-Plough, and Worldwide Clinical Trials; has received consulting fees and grant/research support from Abbott, AstraZeneca, Avid, Baxter, Bristol-Myers Squibb, GlaxoSmithKline, Elan, Eli Lilly, Medivation, Merck, Pfizer, Toyama, and Wyeth; has received educational fees from Alzheimer’s Foundation of America; has received other research support only from Janssen and GE; has received other research support from National Institute on Aging, National Institute of Mental Health, Alzheimer’s Association, Arizona Department of Health Services, and Institute for Mental Health Research; is a stock shareholder in MedAvante and Adamas; and holds a patent for “Biomarkers of Alzheimer’s Disease.” Drs Seward, Burke, Fleisher and Mss Brand and Dougherty have no personal affiliations or financial relationships with any commercial interest to disclose relative to the activity.

Funding/Support

None reported.

DISCLAIMER

The opinions expressed are those of the authors, not of Banner Health or Physicians Postgraduate Press.

Clinical Points

- The use of fluorodeoxyglucose-positron emission tomography (FDG-PET) scans in the workup of patients with dementia can help distinguish between frontotemporal dementia and Alzheimer’s disease.

- Behavioral changes in patients with dementia should be addressed by careful pharmacologic management.

- Clinical characteristics may distinguish Alzheimer’s disease dementia and frontotemporal dementia, but FDG-PET and/or neuropsychological testing may be needed.

This CME activity is expired. For more CME activities, visit cme.psychiatrist.com.

Find more articles on this and other psychiatry and CNS topics:

The Journal of Clinical Psychiatry

The Primary Care Companion for CNS Disorders

References

American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders. Fourth Edition. Arlington, VA: American Psychiatric Association; 2000.

Crum RM, Anthony JC, Bassett SS, et al. Population-based norms for the Mini-Mental State Examination by age and educational level. JAMA. 1993;269(18):2386-2391. PubMed

Farlow MR, Miller ML, Pejovic V. Treatment options in Alzheimer’s disease: maximizing benefit, managing expectations. Dement Geriatr Cogn Disord. 2008;25(5):408-422. doi: 10.1159/000122962 PubMed

Folstein MF, Folstein SE, McHugh PR. “Mini-mental state”: a practical method for grading the cognitive state of patients for the clinician. J Psychiatr Res. 1975;12(3):189-198. doi:10.1016/0022-3956(75)90026-6 PubMed

Gill SS, Anderson GM, Fischer HD, et al. Syncope and its consequences in patients with dementia receiving cholinesterase inhibitors: a population-based cohort study. Arch Intern Med. 2009;169(9):867-873. PubMed

Gollan TH, Montoya RI, Werner GA. Semantic and letter fluency in Spanish-English bilinguals. Neuropsychology. 2002;16(4):562-576. PubMed doi:10.1037/0894-4105.16.4.562

Hodges JR, Davies R, Xuereb J, et al. Survival in frontotemporal dementia. Neurology. 2003;61(3):349-354. PubMed

Kertesz A, Morlog D, Light M, et al. Galantamine in frontotemporal dementia and primary progressive aphasia. Dement Geriatr Cogn Disord. 2008;25(2):178-185. PubMed doi:10.1159/000113034

Knopman DS, DeKosky ST, Cummings JL, et al; Report of the Quality Standards Subcommittee of the American Academy of Neurology. Practice parameter: diagnosis of dementia (an evidence-based review). Neurology. 2001;56(9):1143-1153. PubMed

Links KA, Merims D, Binns MA, et al. Prevalence of primitive reflexes and parkinsonian signs in dementia. Can J Neurol Sci. 2010;37(5):601-607. PubMed

Mendez MF, Shapira JS, McMurtray A, et al. Preliminary findings: behavioral worsening on donepezil in patients with frontotemporal dementia. J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2007;15(1):84-87. PubMed doi:10.1097/01.JGP.0000231744.69631.33

Mendez MF. Frontotemporal dementia: therapeutic interventions. Front Neurol Neurosci. 2009;24:168-178. PubMed doi:10.1159/000197896

Mitrushina M, Boone KB, Razani J, et al. Handbook of Normative Data for Neuropsychological Assessment. Second edition. New York, NY: Oxford University Press; 2005.

Moretti R, Torre P, Antonello RM, et al. Rivastigmine in frontotemporal dementia: an open-label study. Drugs Aging. 2004;21(14):931-937. PubMed doi:10.2165/00002512-200421140-00003

Mungas D. In-office mental status testing: a practical guide. Geriatrics. 1991;46(7):54-58, 63, 66. PubMed

Nasreddine ZS, Phillips NA, Bédirian V, et al. The Montreal Cognitive Assessment, MoCA: a brief screening tool for mild cognitive impairment. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2005;53(4):695-699. doi:10.1111/j.1532-5415.2005.53221.x PubMed

Neary D, Snowden J, Mann D. Frontal lobe dementia and motor neuron disease. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 1990;53(1):23-32.

Neary D, Snowden J, Mann D. Frontotemporal dementia. Lancet Neurol. 2005;4(11):771-780. PubMed

Petersen RC, Smith GE, Waring SC, et al. Mild cognitive impairment: clinical characterization and outcome. Arch Neurol. 1999;56(3):303-308. PubMed doi:10.1001/archneur.56.3.303

Snowden JS, Neary D, Mann DMA. Frontotemporal Lobar Degeneration: Frontotemporal Dementia, Progressive Aphasia, Semantic Dementia. London, England: Churchill Livingstone; 1996.

Voisin T, Touchon J, Vellas B. Mild cognitive impairment: a nosological entity? Curr Opin Neurol. 2003;16(suppl 2):S43-S45. PubMed doi:10.1097/00019052-200312002-00008

Enjoy this premium PDF as part of your membership benefits!