Because this piece does not have an abstract, we have provided for your benefit the first 3 sentences of the full text.

Donald F. Klein, founding member of the American Society of Clinical Psychopharmacology and organizer of the first meeting of the society in May 1992, died on August 7, 2019. He was a leading member of the pioneer generation of the modern era of psychiatry—especially clinical psychopharmacology.

Don Klein was a towering figure, literally and symbolically.

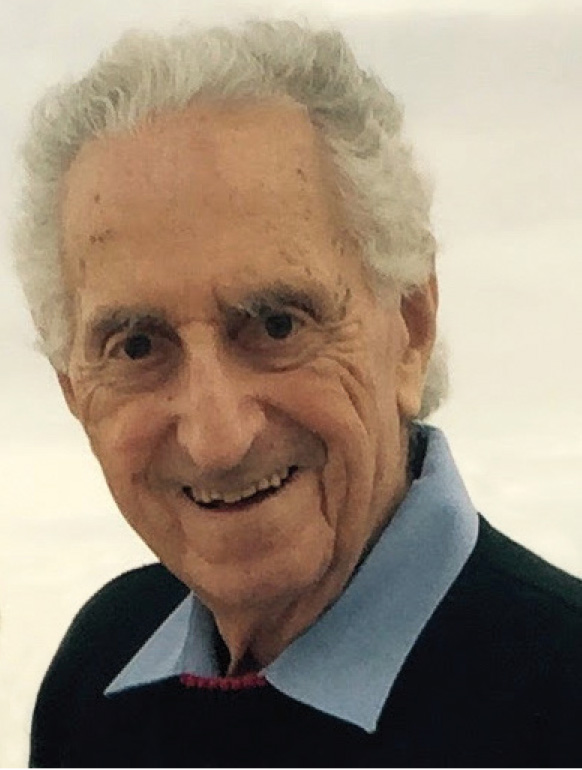

Donald F. Klein, MD, DSc

Donald F. Klein, founding member of the American Society of Clinical Psychopharmacology and organizer of the first meeting of the society in May 1992, died on August 7, 2019. He was a leading member of the pioneer generation of the modern era of psychiatry—especially clinical psychopharmacology.

Don Klein was a towering figure, literally and symbolically. His immeasurable contributions to both clinical psychiatry and psychopharmacology have not always been properly recognized. A list of his publications reads like a history of clinical psychopharmacology, encompassing over 500 observational peer-reviewed papers and over 100 chapters, as well as key books that enabled the field to get off the ground using scientific data (notably, the second edition of Diagnosis and Drug Treatment of Psychiatric Disorders: Adults and Children,1 with Rachel Gittelman Klein, Frederick Quitkin, and Arthur Rifkin). All reflect that he was a great scientist, thoughtful clinician, and extraordinary teacher. He was not only bright, sharp, but an astute and keen observer of human behavior.

One of his first publications, in 1961, was on withdrawal symptoms following discontinuation of imipramine, a clinical issue that is only now getting our full attention. He published extensively on behavioral and other effects of psychotropic drugs. His focus on finding new ways to help his patients led him to investigations in various areas of psychiatry. He established a research program in schizophrenia, where he found premorbid pathology suggesting the need to start treatment as early as possible instead of waiting for the full psychotic symptoms to show themselves. Next, he turned his attention to “atypical depression” and, with the group of clinical researchers at Columbia University, demonstrated that monoamine oxidase inhibitors, rather than tricyclic antidepressants, should be the treatment of choice for this type of depression.

During the 1970s and 1980s, another area—”anxiety”—become the focus of his attention, and his contribution in this area was enormous. His observation of panic attacks, in what was called “anxiety neurosis,” and the fact that some of the patients improved in regard to panic symptoms but not anticipatory anxiety, contributed to our nosology of anxiety disorder. It led to the careful separation of panic disorder, generalized anxiety disorder, and agoraphobia in DSM-III and subsequent DSM editions (Don was a member of the DSM-III Anxiety and Dissociative Disorders Advisory Committee). Knowing that anxiety could be provoked by lactate infusion, he turned to the study of pathophysiology underlying the biology of panic anxiety. He and the group of, at the time, young researchers at Columbia University (eg, Drs Michael Liebowitz, Jack Gorman, and Abby Fyer) studied the induction of panic with lactate in the laboratory setting and later added CO2 to the substances studied in provocation of panic. His observation led him to the hypothesis of the importance of “false suffocation alarm” symptoms in the etiology of panic anxiety. He then turned to other areas of interest: the genetics of panic disorder and the treatment of this disorder. He authored and coauthored a large number of papers addressing treatment of panic, including the use of tricyclic antidepressants, selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors, other medications, and psychotherapy. He was involved even in investigations of intravenous medication in treatment-resistant patients and in lactate-induced panic attacks.

Dr Klein was also a pioneer in the development of treatment of childhood disorders. His work contributed to the inclusion of separation anxiety disorder into our nosologic system. Not everyone knows that he conducted some of the first systematic trials of stimulants in hyperactive children and of medication in children with separation anxiety disorder.

Don Klein was also an astute, caring, and beloved clinician. Interestingly and, again, not well known, Dr Klein trained in psychoanalysis. He was a candidate at the New York Psychoanalytic Institute for 4 years. Yet, he was also a Diplomate of the American Board of Clinical Pharmacology (and the American Board of Psychiatry and Neurology). This broad range of his training and study demonstrates his lifelong desire to understand the human brain-psyche and its behavioral disturbances. He believed that all of his training helped him to better understand the suffering of his patients. He tried to get the best grasp of his patients’ full history—in his private office, he would send new patients an enormous questionnaire covering every corner of their pathology and their life, which he carefully reviewed with them during their first visit. He was concerned about patient reactions to and feelings on psychotropic medications. We both remember conversations with Don in which he revealed that he had tried all psychotropics once, “to see how patients feel” on medications he was prescribing.

In his private life, Dr Klein was devoted to his lifelong partner and collaborator, Dr Rachel Gittelman Klein, and his daughters and grandchildren. He loved French culture (having a French wife and an apartment in Paris certainly helped cultivate it). Some of us were amazed that he was able to read French philosophers in the original language!

It would not make much sense to summarize Dr Klein’s awards and titles, as it seems to us that he felt these to be just the world’s “glories and vanities,” while he was more interested in knowledge, understanding, and science. Throughout his enormously productive life, Don Klein remained a humble man who reminded us that all of the major discoveries of clinical psychopharmacology happened “serendipitously,” as he wrote, during the “seismic shift in psychiatry between 1950 and 1970.”2,3 All of these discoveries were made by keen clinical observers, curious clinicians with scientific minds such as Don Klein.

For us—and globally, as he was internationally well known—he was one of the great scientific minds of the last century. He provided a model of understanding diagnosis, therapeutic benefit, and pathophysiology.3 Donald F. Klein was tough, fair, and easy to discuss science with and work with. In short, a gentleman scientist and a nice guy.

REFERENCES

1.Klein DF, Gittelman R, Quitkin F, et al. Diagnosis and Drug Treatment of Psychiatric Disorders: Adults and Children. 2nd ed. Baltimore, MD: Williams & Wilkins; 1983.

2.Klein DF. The loss of serendipity in psychopharmacology. JAMA. 2008;299(9):1063-1065. PubMed CrossRef

3.Klein DF, Glick ID. Industry withdrawal from psychiatric medication development. Br J Psychiatry. 2014;36(3):259-261. PubMed CrossRef

This PDF is free for all visitors!