Suicide rates in the US have been rising for more than 2 decades,1 with rates among veterans being significantly higher than those of nonveterans.2 Although there is considerable research investigating factors that may influence these increases, we are unaware of any information regarding suicide risk among military retirees. The military retiree population includes veterans who have completed the required years of service to be eligible for retirement pay and may be subject to recall to military duty or who have medically retired based on a qualifying disability. We estimate that retirees comprised nearly 14% of the veteran population in 2022. To document suicide outcomes among the population of veterans who retired from the military, we performed a retrospective study examining suicide risk among military retirees compared to veterans overall. Analyses included the entire population of military retirees alive on January 1, 2012, plus those who first retired during the analysis period. We found elevated suicide risk for medically retired service members and lower suicide risk for those service members who retire based on time in service.

Methods

Army, Air Force, Navy, and Marine Corps retiree populations from 2012–2022 were identified by retirement type using personnel and payroll data from the Veterans Affairs/ Department of Defense Identity Data Repository (VADIR). Due to small counts, retirees from the Space Force and Coast Guard were not included. Risk time for each retiree was calculated from January 1, 2012, or the date of initial retirement, if later, and ended at their date of death from any cause or the end of the observation period, December 31, 2022.

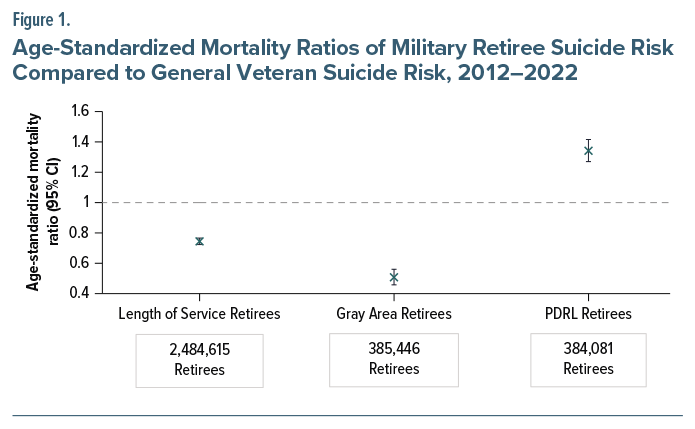

For analyses, “Length of Service” retirees are individuals eligible to receive retirement pay after meeting time in service (Regular retirees3) or time in service plus minimum age requirements (Reserve retirees3). Both must serve at least 20 qualifying years, while Reservists or National Guardsmen must also reach the age of 60 years (or less if qualified). “Gray Area” includes those in the Retired Reserve4 who have met service requirements but not age requirements to receive retirement pay.5 In this analysis, Gray Area retirees move into the Length of Service category upon becoming eligible for receiving retirement pay. The “Permanent Disability Retired List” (PDRL) includes service members medically retired due to permanent disability that developed during service.6 Service members on the Temporary Disability Retired List (TDRL)6 are excluded from this analysis due to data limitations.

Suicide mortality data were obtained from the VA/DoD Mortality Data Repository.7 Retiree suicide risk was compared to that of the overall US veteran population between 2012–2022 using age-standardized mortality ratios (SMRs) and exact 95% confidence intervals (CIs).

This study was conducted as part of ongoing Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) suicide surveillance activities and was exempt from requiring institutional review board approval.

Results

Suicide risk by type of military retirement is presented in Figure 1. Between 2012 and 2022 and excluding TDRL retirees, there were 3,065,413 military retirees. The PDRL consisted of 384,081 retirees (mean annual age=50.0 years) and had elevated suicide risk compared to veterans overall (SMR, 1.32; 95% CI, 1.25–1.39). The Length of Service population included 2,484,615 military retirees (mean annual age=65.0). Compared with veterans overall, these retirees were at decreased risk of suicide (SMR, 0.74; 95% CI, 0.72–0.76) in this period. Gray Area retirees (n=385,446; mean annual age=52.9) were also at decreased suicide risk compared to the veteran population overall (SMR, 0.50; 95% CI, 0.46–0.56). The retiree population was over 90% male; analyses were not adjusted for sex due to small numbers for females, with male-stratified analysis showing negligible difference in results.

Discussion

Veterans who retire based on time served in the US military (Gray Area and Length of Service) were at decreased risk for suicide compared to veterans overall. We speculate that these individuals may have protective factors associated with lower risk for suicide such as coping strategies, financial stability, and social support networks.

In contrast, PDRL retirees had increased suicide risk, which may be attributed to challenges that veterans face when living with disabilities that resulted in their medical retirement. Studies have demonstrated that veterans with physical health difficulties and disabilities are more likely to have had suicidal thoughts and behaviors than other veterans.8,9 This finding along with a previous international study that showed involuntary retirement or being unable to work as risk factors for suicide10 are consistent with findings for PDRL. Many PDRL retirees are initially in the TDRL where eligibility for returning to active duty is determined through regular physical examinations. If the disability stabilizes at a higher severity, they will be transferred to the PDRL.6 This is similar to involuntarily retiring.

This analysis assessed suicide risk among military retirees, including those newly retired and those who retired years prior, and did not examine risk that may be associated specifically with the transition into retirement, an area for potential future investigation. This descriptive analysis was intended to document population-level suicide risk and did not adjust for potential demographic, health, or military service confounders, which could provide additional insights. It is important to consider retirement type, particularly medical retirement, in ongoing and future analyses, but more detailed study of post–military retirement suicide is necessary to inform changes in public health policy and suicide prevention programs. While some subgroups of the overall military retiree population generally have lower suicide risk than the overall veteran population, those retired due to medical disability are at increased risk. Therefore, any suicide prevention initiative should consider the unique and complex mix of risk and protective factors among these veteran retiree populations.

Article Information

Published Online: October 29, 2025. https://doi.org/10.4088/JCP.25br15914

© 2025 Physicians Postgraduate Press, Inc.

J Clin Psychiatry 2026;87(1):25br15914

Submitted: April 8, 2025; accepted September 5, 2025.

To Cite: Ravindran C, Morley SW, Overberg ME, et al. Retired US military veterans and suicide risk. J Clin Psychiatry 2026;87(1):25br15914.

Author Affiliations: Veterans Integrated Service Network (VISN) 2 Center of Excellence for Suicide Prevention, Canandaigua, New York (Ravindran, Morley, Stephens); Army Retirement Services, Department of the Army Headquarters, Washington DC (Overberg).

Corresponding Author: Brady M. Stephens, MS, Center of Excellence for Suicide Prevention, VA Finger Lakes Health Care System, 400 Fort Hill Ave, Canandaigua, NY 14424 ([email protected]).

Relevant Financial Relationships: The authors report no financial affiliation or other relationship relevant to the subject of this report.

Funding/Support: No direct funding or other financial or material support was received for this work.

Editor’s Note: We encourage authors to submit papers for consideration as a part of our Focus on Suicide section. Please contact Philippe Courtet, MD, PhD, at Psychiatrist.com/contact/courtet.

References (10)

- Garnett MF, Curtin SC. Suicide Mortality in the United States, 2002-2022. NCHS Data Brief; 2024. https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/data/databriefs/db509.pdf

- Department of Veterans Affairs (VA). 2024 National Veteran Suicide Prevention Annual Report Findings. 2024. https://www.mentalhealth.va.gov/docs/data-sheets/2024/2024-Annual-Report-Part-2-of-2_508.pdf

- Defense Finance and Accounting Service. Types of Retirement. Accessed July 31, 2024. https://www.dfas.mil/RetiredMilitary/plan/retirement-types/

- Army Reserve. Army Reserve Retirement Services. Accessed September 23, 2024. https://www.usar.army.mil/Retirement/TransfertoRetiredReserve/

- Defense Finance and Accounting Service. Gray Area Retirees. Accessed July 31, 2024. https://www.dfas.mil/RetiredMilitary/plan/Gray-Area-Retirees/

- Defense Finance and Accounting Service. Qualifying for a Disability Retirement. Accessed July 31, 2024. https://www.dfas.mil/retiredmilitary/disability/disability/

- Department of Veterans Affairs (VA). Department of Veterans Affairs, Office of Mental Health and Suicide Prevention. Joint Department of Veterans Affairs and Department of Defense. Mortality Data Repository. Data compiled from the National Death Index. Accessed December 15, 2023. https://www.mirecc.va.gov/suicideprevention/documents/VA_DoD-MDR_Flyer.pdf

- Nichter B, Monteith LL, Norman SB, et al. Differentiating US military veterans who think about suicide from those who attempt suicide: a population-based study. Gen Hosp Psychiatry. 2021;72:117–123. PubMed CrossRef

- Herzog S, Tsai J, Nichter B, et al. Longitudinal courses of suicidal ideation in US military veterans: a 7-year population-based, prospective cohort study. Psychol Med. 2021;19:1–10. PubMed CrossRef

- Page A, Sperandei S, Spittal MJ, et al. The impact of transitions from employment to retirement on suicidal behaviour among older aged Australians. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol. 2021;56(5):759–771. PubMed CrossRef

This PDF is free for all visitors!