Because this piece does not have an abstract, we have provided for your benefit the first 3 sentences of the full text.

To the Editor: Brain tumors can produce psychiatric symptoms, particularly if malignant and fast growing. Among gliomas, growth rate seems to be particularly relevant for the occurrence of mental disturbance, with symptoms in up to 80% of glioblastomas and only 25%-35% of lower-grade astrocytomas. We report a case of glioblastoma multiforme, a very fast-growing brain tumor, initially presenting as acute mania.

A Case of Glioblastoma Masquerading as an Affective Disorder

To the Editor: Brain tumors can produce psychiatric symptoms, particularly if malignant1 and fast growing.2 Among gliomas, growth rate seems to be particularly relevant for the occurrence of mental disturbance, with symptoms in up to 80% of glioblastomas and only 25%-35% of lower-grade astrocytomas.1 We report a case of glioblastoma multiforme, a very fast-growing brain tumor, initially presenting as acute mania.

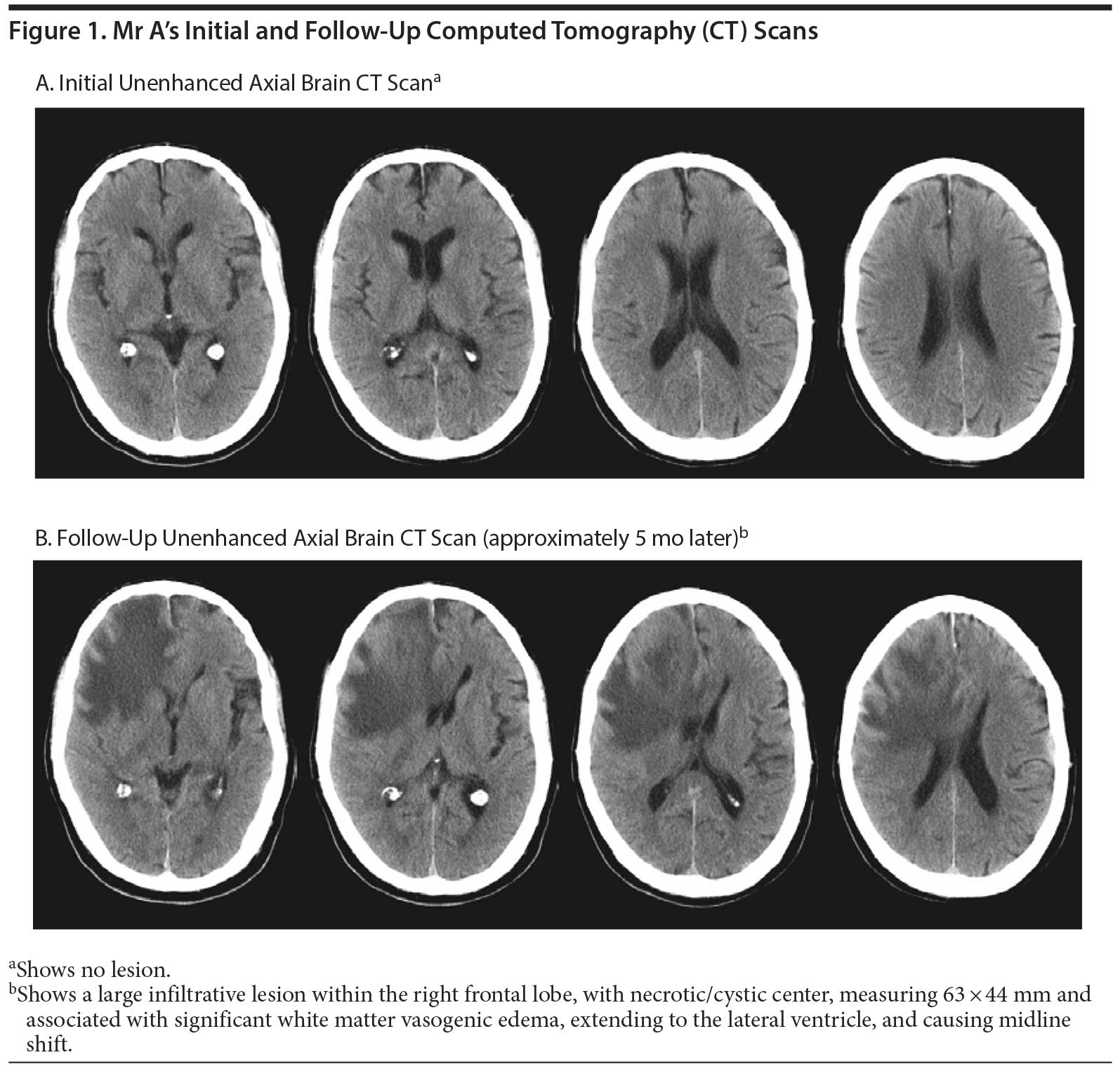

Case report. Mr A, a 76-year-old white man, was admitted to our psychiatric inpatient ward with euphoric mood, increased sexual activity, excessive money spending, and overvalued ideas of grandiose capacity starting 2 months prior. Results of physical and neurologic examination and cognitive evaluation (Mini-Mental State Examination3,4 [MMSE] score: 30/30) were normal, as were brain computed tomography (CT) scan (Figure 1A), electrocardiogram, and chest radiograph results. Blood and urine analyses, including toxicology screening, revealed only mild leucocytosis. Mr A had a 12-year history of treatment-resistant depression (DSM-IV-TR criteria). During the last depressive episode, a neurologist considered the possibility of Parkinson’s disease and dementia and started Mr A on selegiline (5 mg/d), donepezil (10 mg/d), amitriptyline (25 mg/d), and perphenazine (2 mg/d). Depression symptoms remitted 1 year prior to the current episode, leading to discontinuation of amitriptyline and perphenazine. In addition, Mr A had a history of hypertension, benign prostatic hypertrophy, glaucoma, gastric ulcer, and degenerative lumbar disc disease, and, at the onset of the current episode, was also taking telmisartan (40 mg/d) and tamsulosin (0.4 mg/d).

On the basis of a working diagnosis of acute mania (DSM-IV-TR criteria), Mr A was started on valproic acid (1,000 mg/d), risperidone (2 mg/d), and flurazepam (15 mg if needed). Selegiline and donepezil were discontinued, with no adverse consequences. There was a gradual improvement, leading to full symptomatic remission, with no significant side effects, and he was discharged after 1 month with a diagnosis of bipolar disorder (DSM-IV-TR criteria). At his first follow-up consultation 1 month later, Mr A showed marked sedation and significant cognitive deficits (Montreal Cognitive Assessment5,6 score: 18/30; MMSE score: 23/30), prompting reduction of risperidone to 1 mg/d and replacement of flurazepam with lorazepam. At subsequent evaluations, Mr A remained sedated, and his cognitive function further deteriorated, leading to requests for an electroencephalogram, which was normal, and brain magnetic resonance imaging (MRI). Four months after being discharged, Mr A developed left-side hemiparesis and was referred to our emergency department, where a repeat brain CT scan (Figure 1B) revealed a large right frontal lobe tumor, confirmed by the MRI scan and later diagnosed "postoperatively" as glioblastoma.

In late-onset bipolar disorder, there is a higher likelihood of underlying organic causes meriting, as exemplified here, extensive diagnostic testing.7,8 In this patient, while an iatrogenic cause could be considered on initial presentation,9,10 the subsequent follow-up highlights the need for careful longitudinal investigation. We note that a brain CT, concomitant with an inaugural presentation of mania, was normal, and the same examination performed 5 months later revealed a large tumor in the right frontal lobe. Frontal brain tumors can present symptomatically as mood disorders,11-13 with right hemisphere tumors more frequently associated with mania-like syndromes and left hemisphere tumors with depression-like syndromes.11,14 Similar laterality trends have been described for cerebrovascular lesions.15 In Mr A, the use of brain MRI at presentation could possibly have allowed for an earlier diagnosis of the lesion.7 Nevertheless, it is tempting to speculate that the inaugural manic episode was the first expression of a tumor developing in the right frontal lobe, even prior to structural evidence of the lesion, raising interesting possibilities regarding the mechanisms mediating this association.14

REFERENCES

1. Busch E. Physical symptoms in neurosurgical disease. Acta Psychiatr Neurol Scand. 1940;15(3-4):257-290. doi:10.1111/j.1600-0447.1940.tb06757.x

2. Keschner M, Bender MB, Strauss I. Mental symptoms associated with brain tumor: a study of 530 verified cases. JAMA. 1938;110(10):714-718. doi:10.1001/jama.1938.02790100012004

3. Folstein MF, Folstein SE, McHugh PR. "Mini-mental state": a practical method for grading the cognitive state of patients for the clinician. J Psychiatr Res. 1975;12(3):189-198.PubMed doi:10.1016/0022-3956(75)90026-6

4. Morgado J, Rocha CS, Maruta C, et al. Cut-off scores in MMSE: a moving target? Eur J Neurol. 2010;17(5):692-695.PubMed doi:10.1111/j.1468-1331.2009.02907.x

5. Freitas S, Sim×µes MR, Alves L, et al. Montreal Cognitive Assessment (MoCA): normative study for the Portuguese population. J Clin Exp Neuropsychol. 2011;33(9):989-996.PubMed doi:10.1080/13803395.2011.589374

6. Nasreddine ZS, Phillips NA, Bédirian V, et al. The Montreal Cognitive Assessment, MoCA: a brief screening tool for mild cognitive impairment. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2005;53(4):695-699.PubMed doi:10.1111/j.1532-5415.2005.53221.x

7. Arciniegas DB. New-onset bipolar disorder in late life: a case of mistaken identity. Am J Psychiatry. 2006;163(2):198-203.PubMed doi:10.1176/appi.ajp.163.2.198

8. Depp CA, Jeste DV. Bipolar disorder in older adults: a critical review. Bipolar Disord. 2004;6(5):343-367.PubMed doi:10.1111/j.1399-5618.2004.00139.x

9. Benazzi F. Mania associated with donepezil. J Psychiatry Neurosci. 1999;24(5):468-469. PubMed

10. Boyson SJ. Psychiatric effects of selegiline. Arch Neurol. 1991;48(9):902.PubMed doi:10.1001/archneur.1991.00530210028017

11. Belyi BI. Mental impairment in unilateral frontal tumours: role of the laterality of the lesion. Int J Neurosci. 1987;32(3-4):799-810.PubMed doi:10.3109/00207458709043334

12. Direkze M, Bayliss SG, Cutting JC. Primary tumours of the frontal lobe. Br J Clin Pract. 1971;25(5):207-213. PubMed

13. Strauss I, Keschner M. Mental symptoms in cases of tumor of the frontal lobe. Arch Neurol Psychiatry. 1935;33(5):986-1005. doi:10.1001/archneurpsyc.1935.02250170072006

14. Starkstein SE, Boston JD, Robinson RG. Mechanisms of mania after brain injury. 12 case reports and review of the literature. J Nerv Ment Dis. 1988;176(2):87-100.PubMed doi:10.1097/00005053-198802000-00004

15. Cummings JL, Mendez MF. Secondary mania with focal cerebrovascular lesions. Am J Psychiatry. 1984;141(9):1084-1087. PubMed

Author affiliations: Department of Psychiatry and Mental Health (Drs Oliveira-Maia and Barahona-Corrêa) and Department of Neuroradiology (Dr Ruivo), Centro Hospitalar de Lisboa Ocidental; Neuropsychiatry Unit (Drs Oliveira-Maia and Barahona-Corrêa) and Department of Radiology (Dr Ruivo), Champalimaud Clinical Centre, Fundaç×£o Champalimaud; Champalimaud Neuroscience Programme, Fundaç×£o Champalimaud (Dr Oliveira-Maia); and Department of Psychiatry and Mental Health, Nova Medical School, Universidade Nova de Lisboa (Dr Barahona-Corrêa), Lisbon, Portugal.

Potential conflicts of interest: None reported.

Funding/support: None reported.

Published online: December 25, 2014.

Prim Care Companion CNS Disord 2014;16(6):doi:10.4088/PCC.14l01682

© Copyright 2014 Physicians Postgraduate Press, Inc.

Enjoy this premium PDF as part of your membership benefits!