Abstract

The US Administration has moved to declare gestational exposure to acetaminophen (paracetamol) a risk factor for autism spectrum disorder (ASD) and attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) in children. This article examines the science on the subject. Studies suggest that about half of women use acetaminophen during pregnancy; nevertheless, there is no epidemic of neurodevelopmental disorders (NDDs) in offspring. Two large population-based studies, one Swedish and the other Japanese, found that maternal use of acetaminophen during pregnancy was associated with an increased risk of ASD, ADHD, and intellectual disability (ID) in children. However, the risks were very small in fully adjusted analyses; hazard ratios (HRs) were mostly in the 1.05–1.07 range. Importantly, maternal use of aspirin, other NSAIDs, opioids, or antimigraine drugs during pregnancy was also associated with an increased risk of ASD and ADHD (but not ID). Most importantly, in sibling analyses, gestational exposure to acetaminophen, aspirin, and other analgesic drug categories was not associated with an increased risk of NDDs. There are many key points. Acetaminophen has a safety profile that is better than that of alternative treatments. The magnitude of increase in absolute risk for NDDs is very small (eg, by 0.09% at age 10, for ASD). There are many unmeasured confounds that, evenif weak, could nullify the relationship between acetaminophen and NDDs. Sibling analyses suggest that shared genetic and shared environment risk factors (rather than acetaminophen exposure) may explain the NDD risk. Analyses of other analgesic drug groups suggest that pain and inflammation, rather than drug exposure, may also explain the NDD risk. Finally, for reasons that are explained, making acetaminophen unavailable during pregnancy does not mean that the NDD risk will reduce. These points need to be discussed with women in a shared decision-making process that is both equitable and free from guilting.

J Clin Psychiatry 2025;86(4):25f16187

Author affiliations are listed at the end of this article.

On September 22, 2025, the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) announced that it had initiated the process for a label change for acetaminophen (paracetamol), suggesting that acetaminophen use by women during pregnancy may be associated with an increased risk of autism spectrum disorder (ASD) and attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) in offspring.1 In a letter to physicians bearing the same date, the FDA reiterated the concern but struck a more balanced perspective. The letter stated that a cause-effect relationship has not been established, that there are studies that do not support the association, and that the subject is an area of ongoing scientific debate. The letter recommended that clinicians minimize advising pregnant women to use acetaminophen for low-grade fever but acknowledged that the drug is the safest analgesic/antipyretic option during pregnancy.2

The subject is now of global interest because no less than the President of the United States and the US Secretary of the Department of Health and Human Services (HHS) have strongly urged women to refrain from using acetaminophen during pregnancy.3 This article therefore considers the background, the questions, and the evidence related to the subject, with particular reference to 2 very recent and large population-based observational studies.4,5 A formal review is not presented because recent reviews are already available6–8; rather, this article offers a reasoned approach to the evaluation of risk.

Gestational Exposure to Medications and Adverse Outcomes in Offspring

It has been known for more than half a century that drugs used by a woman during pregnancy can affect the fetus.9 The most dramatic example in public memory is the thalidomide tragedy that unfolded in 1961–1962.10 After the thalidomide events, regulatory authorities took far more care to screen medications for gestational risks before approving them for marketing and public use.11 Also, health care professionals and women became more careful about advising and using medicines during pregnancy.12

A limitation of regulatory oversight is that it cannot screen for uncommon adverse outcomes associated with gestational exposure to drugs, especially uncommon outcomes that take many years to appear and be detected. This is especially a problem when there is a large number of other risk factors associated with such outcomes. ASD and ADHD are examples of such outcomes.

Much of the discussion in the rest of this article will focus on ASD. This is because ASD has been singled out in political diatribes.13,14 However, data on ADHD and intellectual disability (ID) risks will also be presented, and readers are reminded that the discussion on acetaminophen-ASD risks applies to ADHD and ID, as well.

Is There Really an Epidemic of Autism?

Earlier in 2025, the US HHS secretary said, “The autism epidemic is running rampant.”15 Is there really an epidemic of autism? The population prevalence of autism among children in Gothenburg, Sweden, was 0.02% in 1978, and the weighted population prevalence of ASD among children and adolescents in the US was 3.42% in 2021–2022.16 However, this 170-fold increase is almost certainly an artifact of variations in methods of assessment; variations in definitions of caseness; broadening of the concept of autism from infantile autism, half a century ago, to ASD, at present; greater awareness and diagnosis of the disorder, especially among girls; and other reasons.16 Finally, exposure to environmental risk factors may also have increased, explaining a part of the increase in the observed prevalence of ASD. However, acetaminophen is not the only risk factor; there are several dozen, and possibly over a hundred, of such risk factors for ASD.16

How Common Is Acetaminophen Use During Pregnancy?

Given the very large number of genetic, gestational, and environmental risk factors for ASD,16 it is not clear why the US government has singled out acetaminophen as a target. A possible explanation is that acetaminophen is widely used during pregnancy.

Acetaminophen is prescribed for pain relief and for fever. It is very likely that an average individual will, across a 9-month period, experience an event (eg, a headache, an injury, a fever) that requires the use of acetaminophen. Given that pregnancy lasts 9 months, and given that pregnancy is associated with back pain and other discomforts, the chances are high that a pregnant woman will need acetaminophen.

What do the data show? In the prospective MotherToBaby birth cohort study conducted in the US, during 2004–2018, 62% of 2,441 pregnant women used acetaminophen during pregnancy. Among users, 58% reported use for <10 days, 13% reported use for 10–19 days, 9% reported use for 20–44 days, and 9% reported use for ≥45 days. Information about duration of use was unavailable for 12% of users.17

In the First Baby prospective cohort study, also conducted in the US, during 2009–2011, 42% of 2,423 women reported that they had used acetaminophen during pregnancy.18 In the prospective Danish National Birth Cohort study, during 1996–2002, 56% of 64,322 women reported using acetaminophen during pregnancy.19 In a Japanese study, during 2005–2022, acetaminophen was dispensed to 40% of 217,602 pregnant women.5

Why Is the Subject Important?

The data from the previous section indicate that, for the past 3 decades and in different parts of the world, about half of pregnancies may have been exposed to acetaminophen. This suggests that even though health care providers and women are aware of the need to limit the use of medications during pregnancy, there is often a need for an analgesic or antipyretic treatment, and acetaminophen may be used because it is considered the safest among available options.2

The Crux of the Matter

Now, here is the crux of the matter. If acetaminophen is the safest among available options but pregnant women are advised to avoid it because of the risk of ASD and ADHD in exposed offspring, then they are caught between a rock and a hard place. These women cannot use acetaminophen because of the alleged risk of a neurodevelopmental disorder (NDD), and they cannot use opiates or nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) because these medications have a poorer general safety profile relative to acetaminophen, and because these medications are also associated with risks to the pregnancy and to the offspring.20–26 So, women must endure pain or fever untreated, which is unfair if the association between paracetamol use and ASD risk is not cause and effect.

As a side note, the benefits of aspirin in pregnancy accrue with low doses (eg, 81–162 mg/d)27; higher doses (325–650 mg, as indicated) are necessary for analgesic and antipyretic action. When low doses of aspirin are already associated with multiple risks,4,28 higher doses may be associated with even larger risks.

Avoiding Acetaminophen: Illogical and Problematic

Avoiding acetaminophen may be illogical because the need for acetaminophen during pregnancy is associated with loading for many risk factors for NDDs in offspring.17 This suggests that confounding may be responsible for an association observed between gestational exposure to acetaminophen and NDDs.

Avoiding acetaminophen and enduring fever may be problematic because fever has itself been associated with gestational, fetal, and neonatal risks.29–32 So, leaving fever untreated is not necessarily a safe option. A caveat here is that it is unclear to what extent the risks result from the fever as opposed to the causes of the fever.

Guilting Women

If pain or fever is so severe as to necessitate acetaminophen during pregnancy, should an NDD be diagnosed in the child born from that pregnancy, the woman would receive blame or suffer guilt because, in the words of the US President, she did not “fight like hell not to take it”13 and “tough it out”14; again, this is unfair if the association between paracetamol use and ASD risk is not cause and effect but a result of confounding.

Acetaminophen May Merely Be a Marker of Risk

Hundreds of genes and dozens of environmental exposures have been associated with an increased risk of ASD.16 The genes for ASD may increase gestational use of acetaminophen through several pathways. For example, the genetic risk for ASD overlaps with the genetic risk for major mental illnesses,33,34 and major mental illnesses are associated with an increased risk of infection, injury, and other conditions that may necessitate the use of acetaminophen. In addition, the genetic risks for ASD and ADHD have also been associated with an increased risk of migraine, pain, and infection during pregnancy, all of which may necessitate acetaminophen. Finally, the genetic risks for these NDDs have also been associated with use of pain medication, including acetaminophen, during pregnancy.35,36

Environmental exposures during pregnancy, such as poverty and malnutrition, may increase the risk of infection and other disorders that, on the one hand, necessitate acetaminophen, and on the other, predispose to NDDs.16 All such genetic and environmental confounds are difficult to identify and accurately measure; so, the risks for acetaminophen exposure, identified in regressions, are inevitably inflated by residual confounding, or may even be solely due to residual confounding. The bottom line is that gestational exposure to acetaminophen may merely be a marker for genetic and environmental risk factors, and hence the risk of NDDs in offspring, rather than a driver of the risk.

Discordant Sibling Pair Analysis

One way of dealing with unmeasured genetic and environmental confounds is to use discordant sibling pair analysis.37 So, if gestational exposure to acetaminophen increases the risk of NDDs in offspring when the comparison group comprises population controls but not when the comparison group comprises sibling controls, it suggests that it is not acetaminophen that is driving the risk but something that is shared between the siblings that is driving the risk. The “something that is shared” is the similarity in genes and environment.

Whether the association between paracetamol use and ASD risk is indeed cause and effect is now examined through the lens of 2 very recent, large, population-based studies; one, from Sweden,4 and the other, from Japan.5

The Swedish Study4

These authors studied all liveborn singleton children (n = 2,480,797) of mothers (n = 1,387,240) in Sweden during 1995–2019, for whom linked data were available in national registers. Data on acetaminophen use during pregnancy were prospectively recorded in interviews or recorded as medication dispensed.4

There were 185,909 (7.5%) offspring gestationally exposed to acetaminophen and 2,294,888 unexposed offspring. Among exposed offspring, across a median of 13.4 years of follow-up, 16,263 (8.7%) were diagnosed with an International Classification of Diseases, Ninth Revision (ICD-9)/ICD-10 NDD; among unexposed offspring, 172,666 (7.5%) received such a diagnosis. The NDD was diagnosed at a median age of 8 years for ID and 12 years for ASD and ADHD.

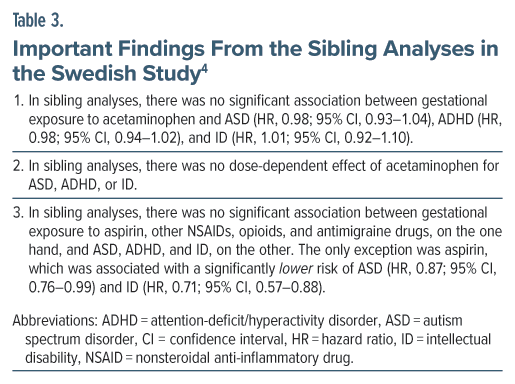

In the sibling pair analysis, there were 94,105 siblings discordant for ASD, 175,070 siblings discordant for ADHD, and 36,899 siblings discordant for ID.

Analyses were adjusted for important covariates, including disposable household income, maternal age, parity, body mass index, smoking status, psychiatric conditions, migraine, chronic pain, infection, fever, arthritis, neuropsychiatric and other drug use, etc.

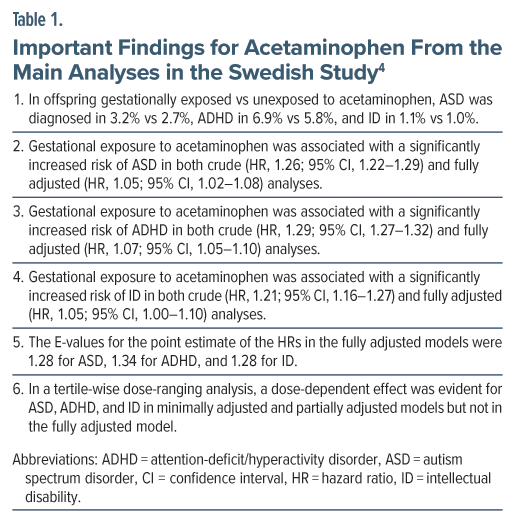

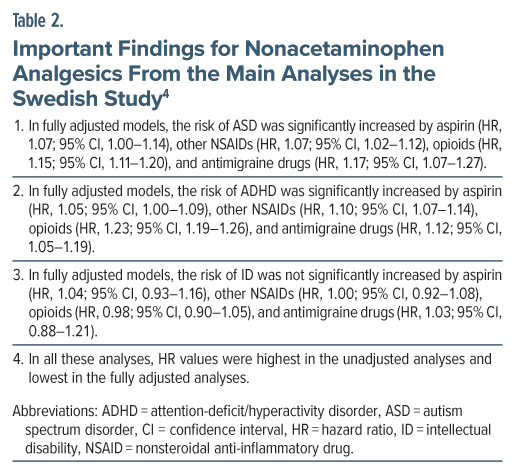

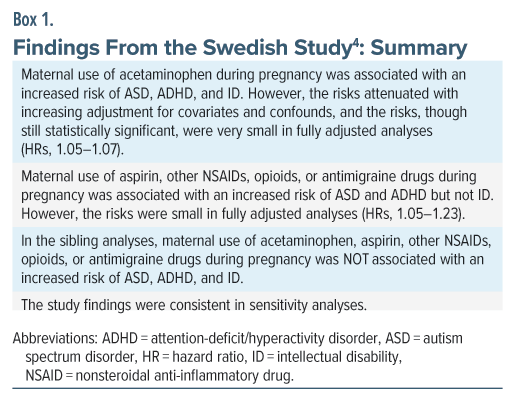

Important findings from the main and sibling analyses are presented in Tables 1, 2, and 3, and these findings are summarized in Box 1. A limitation of this study is that gestational exposure to acetaminophen was uncharacteristically low; so, if exposed pregnancies were misclassified as unexposed pregnancies, the study findings would be biased toward the null.

The Japanese Study5

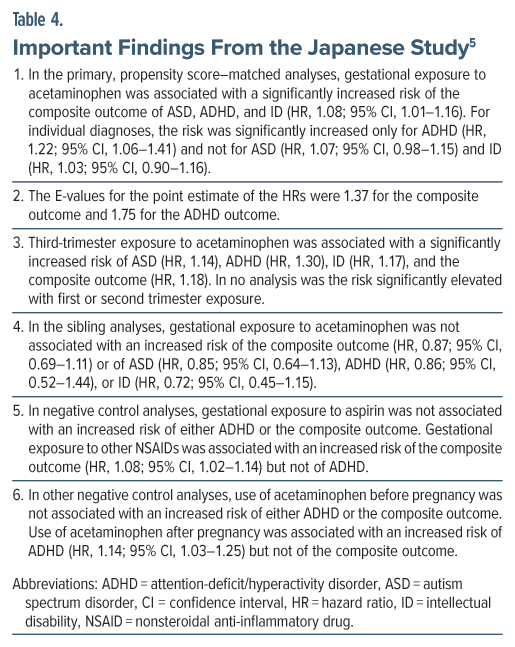

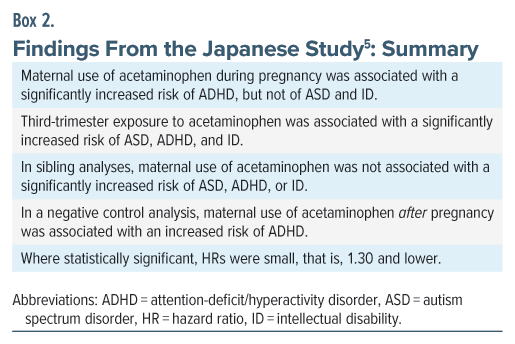

These authors used a nationwide administrative database to identify a birth cohort of 217,602 children (182,830 mothers) born in Japan during 2005–2022. Among these children, 85,853 (39.5%) had been gestationally exposed to acetaminophen during pregnancy.5 The presence of an ICD-10 diagnosis of ASD, ADHD, and ID was examined in these children across a mean follow-up of 4.4 years. In the main analysis, propensity score matching created 42,123 pairs of children with 348,965 person-years of follow-up; thus, the mean duration of follow-up in this subset was 8.3 years. In the sibling analyses (n = 23,593), there were 11,696 children with gestational exposure to acetaminophen and 11,897 unexposed children. Important findings from this study are presented in Table 4 and summarized in Box 2.

There is a troubling matter regarding this study. Nowhere in the main paper did the authors present data on the prevalence of NDDs in exposed and unexposed offspring. However, in Supplementary Table 6, for crude and propensity score–matched analyses, they presented the 6 years cumulative incidence of ASD at 7.4%–9.9%, ADHD at 1.7%–2.4%, and ID at 3.0%–4.2%. The values for ADHD are credible, and those for ID are slightly higher than expected, but the values for ASD are so high that, at least for the ASD analyses, the reader might wish to view the results of these analyses with caution. When NDDs were defined using a diagnostic algorithm (which included the presence of 2 or more instances of diagnosis in the records), the 6-year cumulative incidence dropped to 1.9%–2.4% for ASD, 0.2%–0.3% for ADHD, and 0.4%–0.5% for ID, and none of the associations between acetaminophen exposure and NDD diagnosis in offspring were statistically significant.

A Reasoned Evaluation of Risk

The rest of this article will present a reasoned evaluation of the risk of NDDs following maternal use of acetaminophen during pregnancy. Issues considered will be the magnitude of increase in absolute risk, incomplete adjustment for confounding and the importance of E-values, findings from sibling analyses, maternal use of acetaminophen before and after pregnancy, paternal use of acetaminophen, risks associated with exposure to other analgesic drug groups, the safety of acetaminophen, and whether removal of a risk factor will change real-world risks.

The Magnitude of Increase in Absolute Risk

Whether acetaminophen truly increases the risk of NDDs or is merely a marker of increased risk, the absolute increase in (crude or unadjusted) risk in the population is very small. For example, the increase in prevalence was 0.5% for ASD, 1.1% for ADHD, and 0.1% for ID in the Swedish study.4 The increase in cumulative incidence at 6 years for these disorders was 0.5%, 0.0%, and –0.1%, respectively (with strict criteria for diagnosis), in the Japanese study.5

As a special note, in the Swedish study,4 crude prevalence at age 10 years was increased by only 0.20% for ASD, 0.41% for ADHD, and 0.12% for ID. These values for adjusted prevalences were even lower, at 0.09%, 0.21%, and 0.04%, respectively. That is, the adjusted prevalence increased by approximately 1 in 1,100, 1 in 475, and 1 in 2,500, respectively. These are not alarming numbers, especially when residual confounding may be present.

Incomplete Adjustment for Confounding

The adjusted hazard ratios (HRs) for ASD, ADHD, and ID were 1.05, 1.07, and 1.05 in the Swedish study4 and almost the same at 1.07, 1.22, and 1.03 in the Japanese study.5 These values are very small, and it would take very little for 1 or more unmeasured confounds to bring the HR values to null.

In this context, readers are reminded that there are hundreds of genes and dozens of environmental exposures that have been associated with an increased risk of ASD.16 No study has measured and adjusted for all these exposures, not even the Swedish and Japanese studies.4,5 It is easy to imagine that adjusting for polygenic risk, or for 1 or more environmental exposure, could bring the already low HR values down to null.

As an example, for the Swedish study, the E-value was 1.28 for the adjusted HR for ASD and 1.16 for the lower bound of the 95% confidence interval (CI). This means that an unmeasured confound with a weak association (HR, 1.28) with the exposure and outcome would suffice to bring the HR to 1.00, and that an unmeasured confound with an even weaker association (HR, 1.16) would suffice to lower the 95% CI to include the null.

As a side note, the E-value is the strength of association of an unmeasured confound (or a set of unmeasured confounds) that is necessary to bring an estimate of risk (eg, an HR) to the null value. The E-value can be computed for the point estimate (eg, the HR) and also for the lower bound of the 95% CI of the point estimate. The former tells us how strong the confound needs to be to bring the point estimate to 1.00, and the latter tells us how strong the confound needs to be to bring the 95% CI to a range that includes 1.00; that is, statistical nonsignificance. The lower the E-value the easier it is for a confound to nullify a significant association between a risk factor (eg, acetaminophen exposure) and an outcome (eg, NDD diagnosis).

Findings from Sibling Analyses

In both Swedish and Japanese studies,4,5 the small but statistically significant relationship between gestational exposure to acetaminophen and NDD diagnosis in offspring disappeared in sibling analyses.

Expressed in simple language, in the sibling analyses, whether or not children were diagnosed with NDD depended on sibling relationship rather than on acetaminophen exposure during pregnancy.

This means that risk factors shared between sibs are more important than gestational exposure to acetaminophen as drivers for NDD diagnoses. The risk factors shared between sibs include shared genes and shared environmental influences; that is, the unmeasured confounds referred to in earlier sections.

Maternal Use of Acetaminophen Before or After Pregnancy

If women use acetaminophen only before conceiving or only after pregnancy, there is no logical reason why the drug should affect offspring health. In this context, as an example, the Japanese study5 found that use of acetaminophen after pregnancy was associated with an increased risk of ADHD. This suggests that the propensity to use acetaminophen, or indication(s) for acetaminophen, drive the risk of NDD rather than actual exposure to the drug, regardless of timing of exposure.

Paternal Use of Acetaminophen

A Norwegian prospective cohort study38 found that paternal 6-month prepregnancy use of acetaminophen was associated with offspring risk of ADHD to the same extent as was maternal intrapregnancy use. This suggests confounding by paternal genetic risk factors. The finding is reminiscent of data that show that paternal depression before, during, or after pregnancy each increase the risk of offspring NDDs.39

Exposure to Other Analgesic Drug Groups

The Swedish study4 found that aspirin, other NSAIDs, opioids, and antimigraine drugs each increased the risk of ASD as well as ADHD. It is possible that each of these drug groups, and acetaminophen, truly increases the NDD risk. However, applying Occam’s razor, a more parsimonious explanation is that the common denominator is at least partly if not wholly responsible for the risk. The common denominator would be the pain disorders for which these drugs are prescribed, and inflammatory pathways activated by these disorders may be the mechanism that drives the risk. This has indeed been suggested, such as for ASD.16

An important question here is that if all these different categories of analgesic medication also increase the risk of NDDs, why is the US government targeting only acetaminophen? Rhetorically, why not proscribe all analgesics in pregnancy?

For that matter, why not target all the risk factors for ASD and other NDDs? What is special about acetaminophen that singles it out for attention?

The Relative Safety of Acetaminophen

As reviewed in an earlier section, about 50% of women use acetaminophen during pregnancy. The true number is likely to be even higher because the drug is available over the counter in almost all parts of the world, is considered safe, and is likely to be automatically used for headache, aches and pains, physical discomfort, and fever; that is, conditions that are fairly common across a 9-month period for anybody, including for a woman during the 9-month period of pregnancy. However, despite extensive use during pregnancy, there is no epidemic of NDDs in the population; rather, NDD rates in the population are low. This implies that acetaminophen exposure is responsible (if at all) for only a small contribution to the risk of NDDs. The absolute and adjusted risks presented in this article do show that the effect of exposure is very small and that the identified risk could be easily offset by unmeasured confounds, of which very many exist.

As a reminder, as already stated earlier, the alternatives to acetaminophen, including aspirin, other NSAIDs, opioids, and other drugs, have worse adverse effect profiles.

Removal of Acetaminophen as a Risk Factor

What would happen were acetaminophen to be completely unavailable for use during pregnancy; would there be a decrease in the incidence of NDDs? It is unlikely, and for several reasons. First, there is no evidence, as yet, that gestational exposure to acetaminophen causes NDDs in offspring; the evidence merely suggests that it is a marker of risk, and a weak marker, at that.

Second, if acetaminophen exposure truly increases the risk, the value of the adjusted HR indicates the extent to which the risk in an exposed woman is increased relative to the risk in unexposed women who have the same set of covariates and confounds.40 However, if acetaminophen is not taken when the indication exists, the set of covariates and confounds will no longer remain the same. For example, pain or fever may worsen, resulting in inflammatory burden and increased risk of NDD. Or, some other treatments may be used, including treatments from complementary and alternative systems of medicine, that may be less benign than acetaminophen. In short, there is no assurance, whatsoever, that avoidance of acetaminophen for a valid indication would lower NDD risks.

Third, given the low prevalence of NDDs in the population despite the multitude of highly prevalent risk factors for these disorders, it is likely that the different risk factors converge on common pathways toward the mediation of risk; else, statistical modeling suggests that the prevalence would be substantially higher.40 This opens the possibility that removal of one widely prevalent risk factor (eg, acetaminophen) would merely allow another widely prevalent risk factor to take its place.

Parting Notes

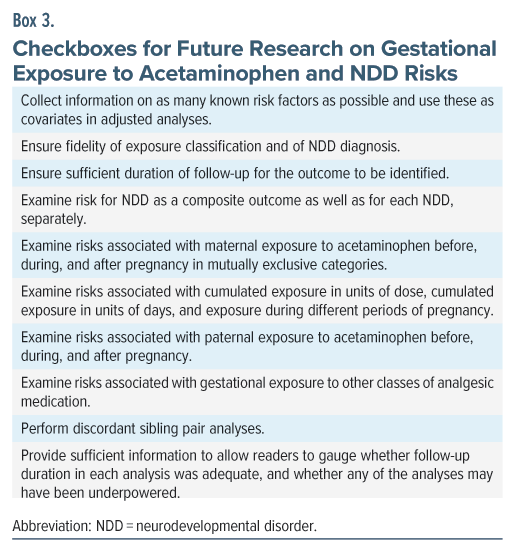

This article does not give a clean chit to acetaminophen. However, because residual confounding is impossible to eliminate in nonrandomized designs, and because a finding that is confounded will remain confounded no matter how consistent the finding is in replicatory research, it is necessary to improve study design and related characteristics to improve confidence in interpreting the results. So, there is a need not for more studies but for better studies; that is, studies that are good in design, methods of analysis, and reporting. Suggestions are provided in Box 3.

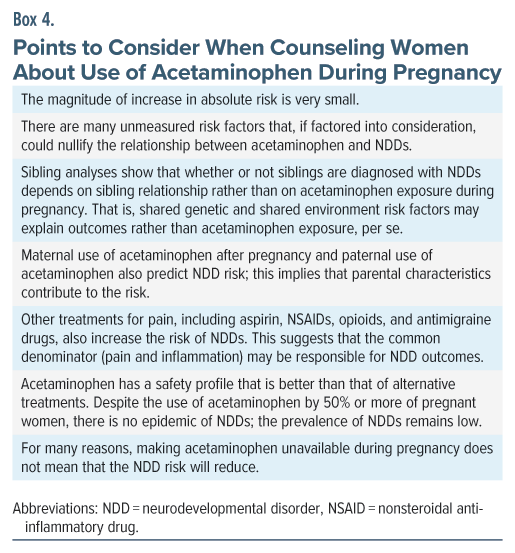

From a scientific perspective, although available data suggest that acetaminophen exposure during pregnancy is a marker rather than a cause of NDDs in offspring, the decision on whether or not to use the drug to treat fever or pain during pregnancy should be based on a shared decision-making process. Points for consideration, as discussed in this article, are summarized in Box 4.

Finally, whatever the choice made, women should understand that it was a reasoned decision taken with professional guidance; they should not be made to feel guilty for their choice.

Article Information

Published Online: November 10, 2025. https://doi.org/10.4088/JCP.25f16187

© 2025 Physicians Postgraduate Press, Inc.

To Cite: Andrade C. Maternal use of acetaminophen (paracetamol) during pregnancy and neurodevelopmental disorders in offspring: a reasoned evaluation of risk. J Clin Psychiatry 2025;86(4):25f16187.

Author Affiliations: Department of Clinical Psychopharmacology and Neurotoxicology, National Institute of Mental Health and Neurosciences, Bangalore, India; Department of Psychiatry, Kasturba Medical College, Manipal Academy of Higher Education, Manipal, India.

Corresponding Author: Chittaranjan Andrade, MD, Department of Clinical Psychopharmacology and Neurotoxicology, National Institute of Mental Health and Neurosciences, Bangalore 560029, India ([email protected]).

Relevant Financial Relationships: None.

Funding/Support: None.

Each month in his online column, Dr Andrade considers theoretical and practical ideas in clinical psychopharmacology with a view to update the knowledge and skills of medical practitioners who treat patients with psychiatric conditions.

Each month in his online column, Dr Andrade considers theoretical and practical ideas in clinical psychopharmacology with a view to update the knowledge and skills of medical practitioners who treat patients with psychiatric conditions.

Department of Clinical Psychopharmacology and Neurotoxicology, National Institute of Mental Health and Neurosciences, Bangalore, India. Please contact Chittaranjan Andrade, MD, at Psychiatrist.com/contact/andrade.

References (40)

- US Food and Drug Administration. FDA responds to evidence of possible association between autism and acetaminophen use during pregnancy. September 22, 2025. Accessed October 6, 2025. https://www.fda.gov/news-events/press-announcements/fda-responds-evidence-possible-association-between-autism-and-acetaminophen-use-during-pregnancy

- US Food and Drug Administration. Notice to physicians on the use of acetaminophen during pregnancy. September 22, 2025. Accessed October 6, 2025. https://www.fda.gov/media/188843/download?attachment

- Horton R. Offline: those one should not forgive. Lancet. 2025;406(10511):1454. PubMed

- Ahlqvist VH, Sjöqvist H, Dalman C, et al. Acetaminophen use during pregnancy and children’s risk of autism, ADHD, and intellectual disability. JAMA. 2024;331(14):1205–1214. PubMed

- Okubo Y, Hayakawa I, Sugitate R, et al. Maternal acetaminophen use and offspring’s neurodevelopmental outcome: a nationwide birth cohort study. Paediatr Perinat Epidemiol; 2025.

- Damkier P, Gram EB, Ceulemans M, et al. Acetaminophen in pregnancy and attention-deficit and hyperactivity disorder and autism spectrum disorder. Obstet Gynecol. 2025;145(2):168–176. PubMed

- Bérard A, Cottin J, Leal LF, et al. Systematic review and meta-analysis: acetaminophen use during pregnancy and the risk of neurodevelopmental disorders in childhood. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2025;30(25):S0890–S8567.

- Prada D, Ritz B, Bauer AZ, et al. Evaluation of the evidence on acetaminophen use and neurodevelopmental disorders using the navigation Guide methodology. Environ Health. 2025;24(1):56. PubMed

- Baker JB. The effects of drugs on the foetus. Pharmacol Rev. 1960;12:37–90. PubMed

- Dally A. Thalidomide: was the tragedy preventable? Lancet. 1998;351(9110):1197–1199. PubMed

- Kim JH, Scialli AR. Thalidomide: the tragedy of birth defects and the effective treatment of disease. Toxicol Sci. 2011;122(1):1–6. PubMed

- Kennedy D, Batagol R. Drug safety in pregnancy. Aust Prescr. 2025;48(1):5–9. PubMed

- Tager-Flusberg H, Singer A, Lee BK, et al. “This may be the most difficult day in my career”: experts react to Trump’s autism remarks. The New York Times; September 23, 2025. Accessed October 7, 2025. https://www.nytimes.com/2025/09/23/opinion/experts-autism-trump-kennedy.html

- Pearson H, Ledford H. Trump links autism and Tylenol: is there any truth to it? Nature. 2025;646(8083):13–14. PubMed

- US Department of Health and Human Services. “Autism Epidemic Runs Rampant,” New Data Shows 1 in 31 Children Afflicted. Press release; April 15, 2025. Accessed October 7, 2025. https://www.hhs.gov/press-room/autism-epidemic-runs-rampant-new-data-shows-grants.html

- Andrade C. Autism spectrum disorder, 1: genetic and environmental risk factors. J Clin Psychiatry. 2025;86(2):25f15878. PubMed

- Bandoli G, Palmsten K, Chambers C. Acetaminophen use in pregnancy: examining prevalence, timing, and indication of use in a prospective birth cohort. Paediatr Perinat Epidemiol. 2020;34(3):237–246. PubMed

- Sznajder KK, Teti DM, Kjerulff KH. Maternal use of acetaminophen during pregnancy and neurobehavioral problems in offspring at 3 years: a prospective cohort study. PLoS One. 2022;17(9):e0272593. PubMed

- Liew Z, Ritz B, Rebordosa C, et al. Acetaminophen use during pregnancy, behavioral problems, and hyperkinetic disorders. JAMA Pediatr. 2014;168(4):313–320. PubMed

- Wen X, Belviso N, Murray E, et al. Association of gestational opioid exposure and risk of major and minor congenital malformations. JAMA Netw Open. 2021;4(4):e215708. PubMed

- Esposito DB, Huybrechts KF, Werler MM, et al. Characteristics of prescription opioid analgesics in pregnancy and risk of neonatal opioid withdrawal syndrome in newborns. JAMA Netw Open. 2022;5(8):e2228588. PubMed

- Kelty E, Rae K, Jantzie LL, et al. Prenatal opioid exposure and immune-related conditions in children. JAMA Netw Open. 2024;7(1):e2351933. PubMed

- Bosworth OM, Padilla-Azain MC, Adgent MA, et al. Prescription opioid exposure during pregnancy and risk of spontaneous preterm delivery. JAMA Netw Open. 2024;7(2):e2355990. PubMed

- Hammers AL, Sanchez-Ramos L, Kaunitz AM. Antenatal exposure to indomethacin increases the risk of severe intraventricular hemorrhage, necrotizing enterocolitis, and periventricular leukomalacia: a systematic review with metaanalysis. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2015;212(4):505.e1–13. PubMed

- Chen X, Yang Y, Chen L, et al. Pregnancy outcomes and birth defects in offspring following non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs exposure during pregnancy:systematic review and meta-analysis. Reprod Toxicol. 2024;125:108561. PubMed

- Tain YL, Li LC, Kuo HC, et al. Gestational exposure to nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs and risk of chronic kidney disease in childhood. JAMA Pediatr. 2025;179(2):171–178. PubMed

- Henderson JT, Vesco KK, Senger CA, et al. Aspirin use to prevent preeclampsia and related morbidity and mortality: updated evidence report and systematic review for the US Preventive Services Task Force. JAMA. 2021;326(12):1192–1206. PubMed

- Hastie R, Tong S, Wikström AK, et al. Aspirin use during pregnancy and the risk of bleeding complications: a Swedish population-based cohort study. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2021;224(1):95.e1–95.e12. PubMed

- Dreier JW, Andersen AM, Berg-Beckhoff G. Systematic review and meta-analyses: fever in pregnancy and health impacts in the offspring. Pediatrics. 2014; 133(3):e674–e688. PubMed

- Antoun S, Ellul P, Peyre H, et al. Fever during pregnancy as a risk factor for neurodevelopmental disorders: results from a systematic review and meta-analysis. Mol Autism. 2021;12(1):60. PubMed

- Shi FP, Huang YY, Dai QQ, et al. Maternal common cold or fever during pregnancy and the risk of orofacial clefts in the offspring: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Cleft Palate Craniofac J. 2023;60(4):446–453. PubMed

- Ling Q, Wan H. The effect of intrapartum maternal fever on neonatal outcomes: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Front Pediatr. 2025;13:1571732. PubMed

- Lee PH, Anttila V, Won H, et al. Cross-Disorder Group of the Psychiatric Genomics Consortium. Genomic relationships, novel loci, and pleiotropic mechanisms across eight psychiatric disorders. Cell. 2019;179(7):1469–1482.e11. PubMed

- Andrade C. Genes as unmeasured and unknown confounds in studies of neurodevelopmental outcomes after antidepressant prescription during pregnancy. J Clin Psychiatry. 2020;81(3):20f13463. PubMed

- Leppert B, Havdahl A, Riglin L, et al. Association of maternal neurodevelopmental risk alleles with early-life exposures. JAMA Psychiatry. 2019;76(8):834–842. PubMed

- Havdahl A, Wootton RE, Leppert B, et al. Associations between pregnancy-related predisposing factors for offspring neurodevelopmental conditions and parental genetic liability to attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder, autism, and schizophrenia: the Norwegian Mother, Father and Child Cohort Study (MoBa). JAMA Psychiatry. 2022;79(8):799–810. PubMed

- Andrade C. Discordant sibling pair comparisons in observational studies: a research design simply explained. J Clin Psychiatry. 2025;86(2):25f15843. PubMed

- Ystrom E, Gustavson K, Brandlistuen RE, et al. Prenatal exposure to acetaminophen and risk of ADHD. Pediatrics. 2017;140(5):e20163840. PubMed

- Andrade C. Paternal depression as a risk factor for neurodevelopmental disorders in offspring: implications for maternal depression and its treatment during pregnancy. J Clin Psychiatry. 2020;81(6):20f13785. PubMed

- Andrade C. Autism spectrum disorder, 2: observations on the imprecision of the numerical value of risk when examining predictors of risk in regression. J Clin Psychiatry. 2025;86(2):25f15918. PubMed

This PDF is free for all visitors!