Abstract

Objective: This study describes recent trends in benzodiazepine prescribing to US adults and characterizes patients who receive benzodiazepines and other central nervous system (CNS) depressants.

Method: This repeated cross-sectional study analyzed benzodiazepine use by adults (ages ≥18 years) in the 2018–2022 Medical Expenditure Panel Surveys, which are nationally representative surveys of the civilian noninstitutionalized population. We examined sex-adjusted annual trends (2018–2022) in benzodiazepine use by age group (ages 18–35, 36–55, and ≥56 years) and pooled marginal differences by age group in any benzodiazepine use and in benzodiazepine use and other CNS-depressant medications, stratified by sociodemographic and clinical characteristics.

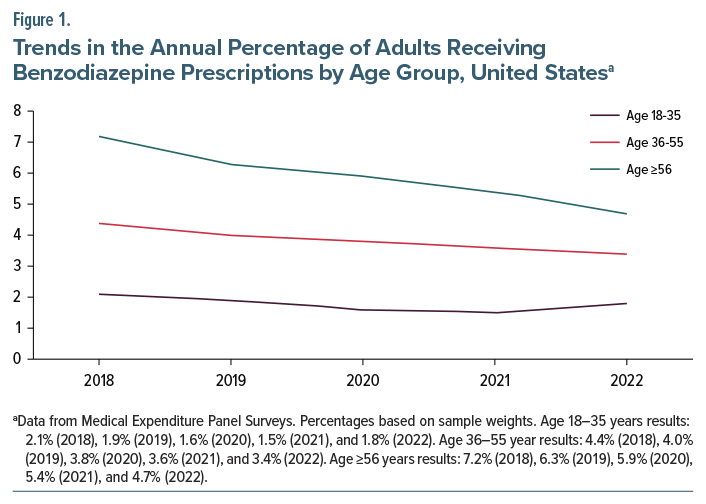

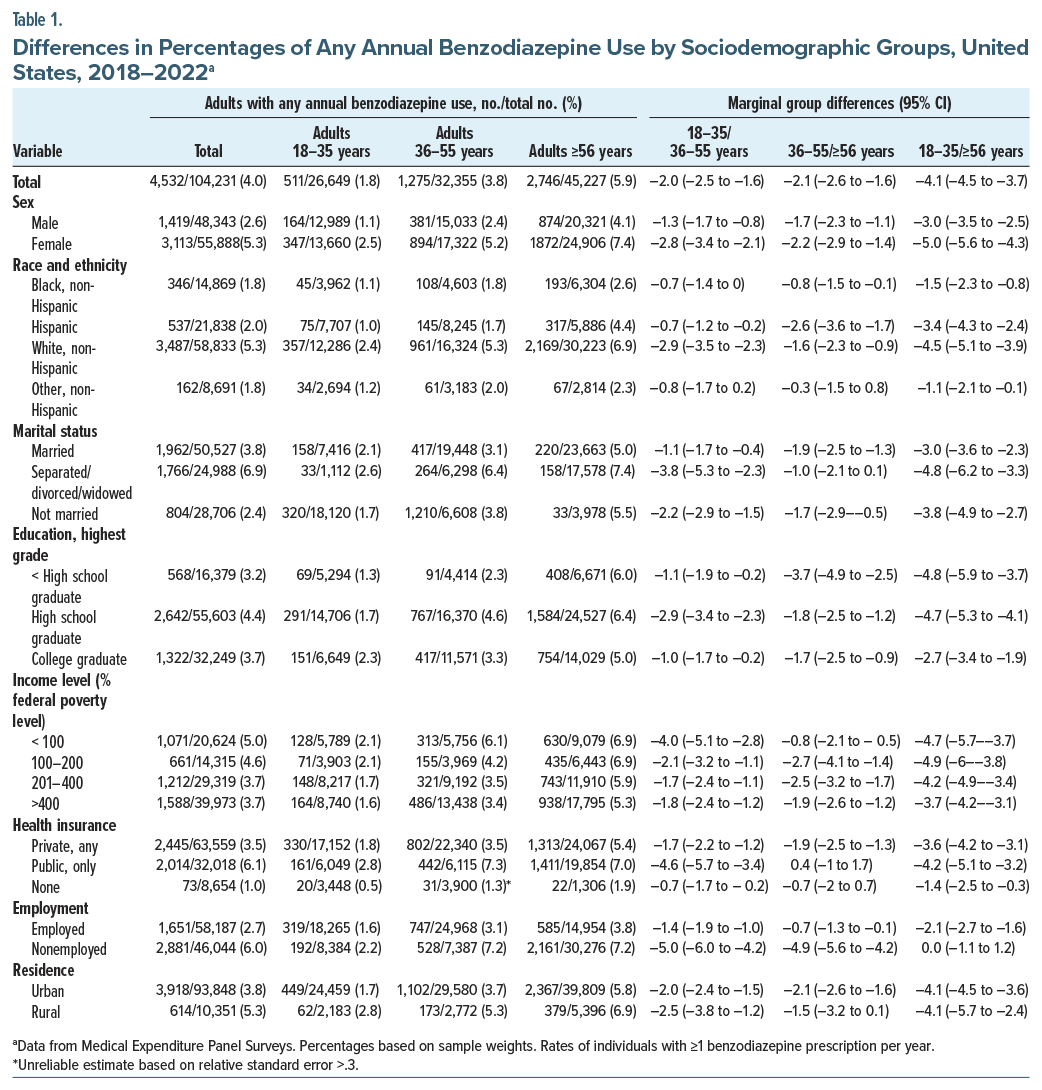

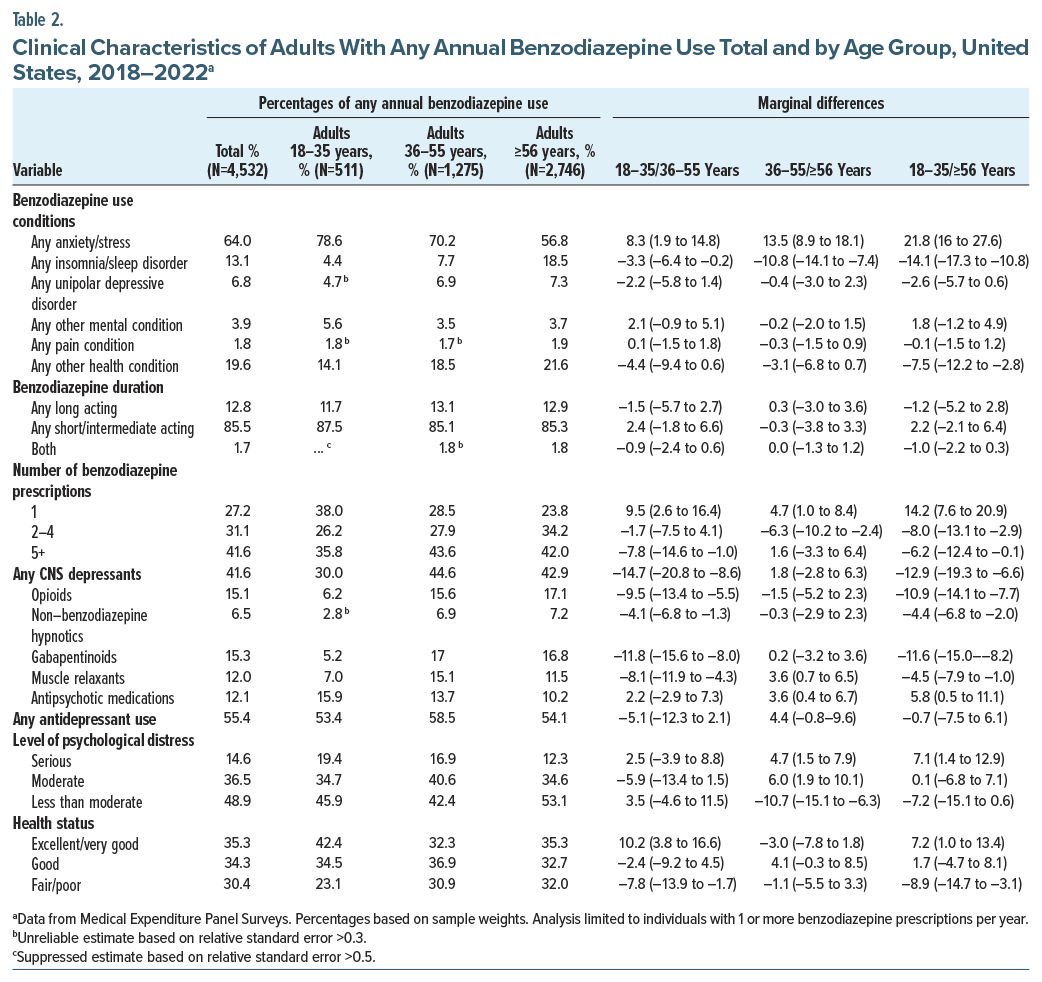

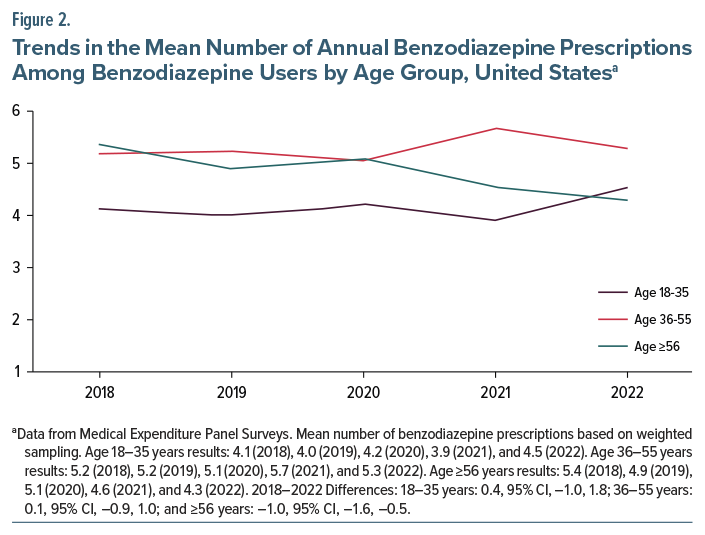

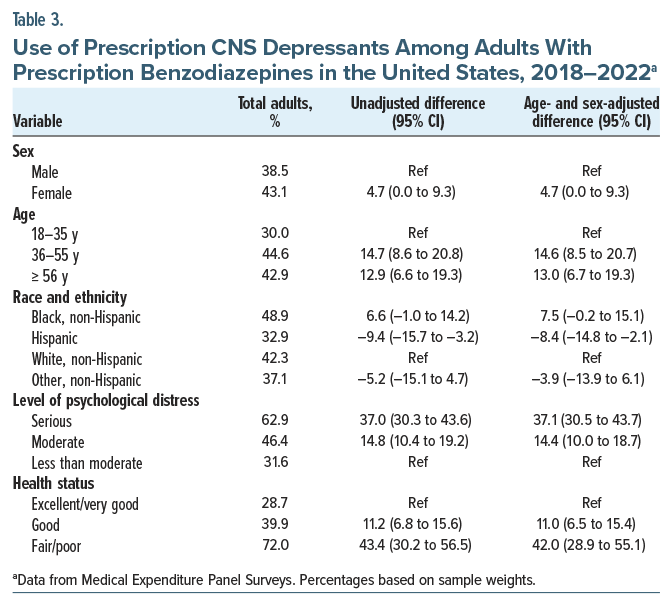

Results: The analysis involved 104,231 participants. Between 2018 and 2022, annual benzodiazepine use by US adults decreased from 4.7% to 3.4%. This included a greater decrease for adults ages ≥56 years (7.2% to 4.7%) than for those ages 36–55 years (4.4% to 3.4%) or 18–35 years (2.1% to 1.8%). Approximately 41.6% adults treated with benzodiazepines also received other CNS-depressant medications in the same year including a higher percentage aged 36–55 years (44.6%) or ≥56 years (42.9%) than 18–35 years (30.0%). Most benzodiazepine-treated adults with fair or poor general health (72.0%) or with serious psychological distress (62.9%) also received other CNS-depressant medications.

Conclusions: Benzodiazepine treatment decreased among US adults between 2018 and 2022, with a greater decline among adults ≥56 years than those 36–55 or 18–35 years. Prescription of benzodiazepines to adults who also received other CNS depressants was common, especially among adults in fair or poor general health or with serious psychological distress.

J Clin Psychiatry 2026;87(1):25m16125

Author affiliations are listed at the end of this article.

See commentary by Silberman

Systematic study and clinical experience support the effectiveness of benzodiazepines for treating insomnia,1 some anxiety disorders,2 alcohol withdrawal,3 catatonia,4 and seizures5 and as an adjunctive treatment for depression,6 while longitudinal studies have shown that only a small percentage of patients who use them long term require dose escalation.7–9 Yet, considerable controversy exists regarding the appropriate role of benzodiazepines in clinical practice. Concern exists over benzodiazepine misuse,10 tolerance to their hypnotic effects,11 and withdrawal syndromes,12 as well as risks of falls and fractures,13 motor vehicle crashes,14 impaired cognition,15 and overdose.16 In the United States, benzodiazepine-related overdose deaths, a great majority of which also involve opioids, alcohol, cocaine, stimulants, or other drugs, increased from 0.46 per 100,000 adults in 2000 to 2.96 per 100,000 adults in 2019.17 As adults age, they become more sensitive to adverse benzodiazepine effects. This increased vulnerability is related to slower metabolism, decreased clearance, longer drug half-life,18 and age-related increased pharmacodynamic sensitivities.19 As a result, the American Geriatrics Society recommends avoiding prescription of benzodiazepines to older adults when possible.20

Risks of respiratory suppression associated with benzodiazepines increase when they are prescribed together with opioids or other medications that depress the central nervous system (CNS).21 Between 1990 and 2016, the percentage of US office-based visits including prescriptions for benzodiazepines and opioids or other CNS depressants tripled,22 indicating the growing potential importance of these drug-drug interactions. Because the rate of US benzodiazepine prescribing increases sharply with age, especially after the age of 55 years,23 it is important to understand the extent to which prescription of benzodiazepines and other CNS depressants occurs among this age group, given the general increase in polypharmacy with advancing age.24

Between 1996 and 2013, the number of US adults who filled benzodiazepine prescriptions increased by 67%, from 8.1 million to 13.5 million, and the quantity of benzodiazepines they obtained more than tripled.25 With this historical context, we evaluated national trends in prescription benzodiazepine use across adult age groups in the US. We also characterized age-related patterns in benzodiazepine treatment, including a focus on adults who received prescriptions for benzodiazepines and other CNS depressants in the same year. Prior to performing these analyses, we hypothesized that among benzodiazepine-treated adults, older compared to middle-aged or younger individuals would have higher risks of also receiving other CNS-depressant medications.

METHODS

Data Source

The 2018–2022 Medical Expenditure Panel Surveys (MEPS), conducted by the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality, produce nationally representative estimates of service use by the civilian noninstitutionalized population. The surveys employ an overlapping panel design. New nationally representative household samples are selected each year and are interviewed 5 times over a 2-year period. During the COVID-19 pandemic, this schedule was temporarily extended for 2 panels to 9 rounds over 4 years. Detailed information concerning fielding the survey and nonresponse adjustment is provided elsewhere.26 With respondent oral consent, English and Spanish survey versions were administered via computer-assisted personal interviews. The following analyses include participants aged ≥18 years from the 2018 (n=22,227), 2019 (n =21,305), 2020 (n=21,138), 2021 (n=21,988), and 2022 (n=17,573) surveys.

Due to use of deidentified data, these analyses were exempted from human participants review by the New York State Psychiatric Institute Institutional Review Board.

Study Groups

Respondents were partitioned into 3 age groups: 18–35 years, 36–55 years, and ≥56 years with age cut points based on national benzodiazepine use patterns.22

Benzodiazepines and Other CNS Depressants

During each survey year, participants were classified by whether they purchased or otherwise obtained ≥1 benzodiazepine prescriptions (Supplementary Table 1). Following the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA), we defined “other CNS-depressant medications” to include prescribed opioids, nonbenzodiazepine hypnotics, gabapentinoids, muscle relaxants, and antipsychotic medications (Supplementary Table 1).27 A separate variable included respondents receiving ≥1 benzodiazepine prescription and ≥1 other CNS medication in the same year. Ninety-three percent of participants with benzodiazepines and other CNS depressants prescribed in the same year received both prescriptions in the same survey round (data not shown in tables).

Other Clinical Characteristics

Participants reported reasons for each prescription that were classified as anxiety or stress, insomnia or sleep disorder, unipolar depressive disorder, other mental condition, pain conditions, or other conditions (Supplementary Table 1). A count variable defined the number of benzodiazepine prescriptions received during each survey year (1, 2–4, 5+). A continuous variable was used in the analysis of mean annual benzodiazepine prescriptions. Benzodiazepines were also classified into long-and short-acting agents (Supplementary Table 1).

Psychological distress was measured with the Kessler-6 (K6), which evaluates past 30-day frequency on a 0 to 4 scale of feeling so sad that nothing could cheer the individual up, nervous, restless or fidgety, hopeless, that everything was an effort, and worthless.28 Scores of ≥13 defined serious psychological distress, 12 to 5 defined moderate distress, and <5 defined less than moderate distress. General health status was assessed as excellent/very good, good, or fair/poor.

Sociodemographic Characteristics

Sociodemographic characteristics as reported by household respondents included sex; race and ethnicity; current marital status; highest education level; annual family income in multiples of the federal poverty level29; health insurance hierarchically classified as any private, only public, or none; employment status; and residence defined as within a metropolitan (urban) or nonmetropolitan (rural) county. Public health insurance included Medicare, Medicaid/SCHIP, and Veterans Health Administration coverage. Race and ethnicity groups included Black non-Hispanic, Hispanic, Other, non-Hispanic, and White non-Hispanic. The “Other, non-Hispanic” group included American Indian/Alaska Native, Asian, Native Hawaiian/Pacific Islander, and multiple races.

Analytic Plan

For each survey year, we determined the percentage of adults using benzodiazepines overall and stratified by age group. Logistic regression models with predictive marginal means tested for differences adjusted by sex from 2018 to 2022 (study period). Interaction terms (age group × study period) were added to evaluate whether trends in benzodiazepine use significantly varied across groups during this period. Among adults using benzodiazepines, the mean annual number of prescriptions was calculated for each group, and trend analyses were performed.

To increase power, we combined the 5 study years and determined the annual percentage of adults overall and for each age group who received ≥1 benzodiazepine prescription stratified by sociodemographic characteristics. Logistic regressions with marginal means were used to test for age group differences in benzodiazepine use comparing younger to middle-aged adults, younger to older adults, and middle-aged to older adults. Among benzodiazepine-treated adults, age group pairwise comparisons were performed by clinical characteristics. Also among benzodiazepine-treated adults, age-and sex-adjusted models tested differences in the percentages receiving other CNS stimulant medications within the same year by age, sex, race and ethnicity, level of distress, and general health status group.

Because no adjustments were made for multiple comparisons (2-sided α=0.05), confidence intervals should be interpreted with caution. All analyses were performed using R 4.4.0 and corrected for the complex multistage clustered and stratified design of the MEPS using the survey library, which also account for the repeated observations in the sample.

RESULTS

Trends and Patterns of Prescription Benzodiazepine Use

Prescription benzodiazepine use among US adults significantly decreased from 4.7% in 2018 to 3.4% in 2022 (Figure 1). The decrease was greater for adults aged ≥56 years (7.2%–4.7%) than for those 36–55 years (4.4%–3.4%) or 18–35 years (2.1%–1.8%) (Figure 1).

During 2018–2022, separated, divorced, or widowed individuals (6.9%); publicly insured adults (6.1%); and nonemployed persons (6.0%) had the highest rates of benzodiazepine use, while uninsured persons (1.0%); Black non-Hispanic adults (1.8%); and the “Other” non-Hispanic group (1.8%) had the lowest (Table 1).

Benzodiazepine Use by Age Group

Among the 3 age groups, benzodiazepine use was highest for adults aged ≥56 years (5.9%) followed by those aged 36–55 years (3.8%) and lowest for those aged 18–35 years (1.8%) (Table 1). With only a few exceptions, similar age patterns were observed across sex, race and ethnicity, marital status, education, income, health insurance status, employment, and residence groups (Table 2). For publicly insured individuals, benzodiazepine use was 7.3% for adults aged 36–55 years and 7.0% for adults aged ≥56 years, while for nonemployed individuals, benzodiazepine use was 7.2% for both adults aged 36–55 and ≥56 years. Among adults aged 56 and over with ≥1 annual benzodiazepine prescription, the mean number of prescriptions declined from 5.4 in 2018 to 4.3 in 2022 (difference, –1.0, 95% CI: −1.6 to −0.5) (Figure 2).

Clinical Characteristics of Benzodiazepine Use by Adult Age

Benzodiazepine treatment of anxiety or stress accounted for a higher percentage of benzodiazepine use by adults aged 18–35 years (78.6%) than 36–55 years (70.2%) or ≥56 years (56.8%) (Table 2). By contrast, benzodiazepine treatment of insomnia or sleep disorders accounted for a higher percentage of use by adults aged ≥55 years (18.5%) than 36–55 years (7.7%) or 18–35 years (4.4%).

The distribution of long-and short-acting benzodiazepine use did not differ across the age groups. However, a larger percentage of the adults aged 18–35 years (38.0%) than 36–55 years (28.5%) or ≥56 years (23.8%) received only 1 benzodiazepine prescription, while a smaller percentage aged 18–35 years (35.8%) than 36–55 years (43.6%) or ≥56 years (42.0%) received ≥5 annual benzodiazepine prescriptions. In all 3 groups, slightly over half received antidepressants in the same year.

Among adults with benzodiazepine use, serious psychological distress was more common in adults aged 18–35 years (19.4%) and 36–55 years (16.9%) than ≥56 years (12.3%). Moderate distress was less common among adults aged ≥56 years (34.6%) than 36–55 years (40.6%). Conversely, fair or poor general health status was more common in adults aged ≥56 years (32.0%) and 36–55 years (30.9%) than 18–35 years (23.1%).

Prescription of Benzodiazepines and Other CNS Depressants

Approximately 4 in 10 (41.6%) adults treated with benzodiazepines also received other CNS depressants in the same year (Table 2). Among the benzodiazepine-treated adults, those aged 36–55 years (44.6%) and ≥56 years (42.9%) were more likely than those 18–35 years (30.0%) to receive other CNS depressants (Table 2). This age pattern was observed for same-year use of opioids, nonbenzodiazepine hypnotics, gabapentinoids, and muscle relaxants. Use of muscle relaxants and antipsychotic medications was more common among adults aged 36–55 years than ≥56 years treated with benzodiazepines. Among benzodiazepine-treated adults, use of antipsychotics was also more common for those aged 18–35 years than for those aged 36–55 years or ≥56 years.

In age and sex adjusted analyses of benzodiazepine-treated adults, same-year use of other CNS depressants was higher for females than males, adults aged 36–55 years and ≥56 years than 18–35 years, Hispanic than White non-Hispanic individuals, adults with serious or moderate psychological distress than less than moderate distress, and adults in fair/poor or good general health than in excellent/very good health (Table 3). Most benzodiazepine-treated adults with serious distress (62.9%) or in fair/poor general health (72.0%) were also prescribed other CNS depressants.

DISCUSSION

Benzodiazepines can provide rapid relief of insomnia,1 anxiety,2 alcohol withdrawal,3 catatonia,4 and seizures.5 Our study identified 4 major findings regarding benzodiazepine prescribing patterns in the United States. First, overall benzodiazepine prescribing declined between 2018 and 2022, primarily driven by reduced use among adults 56 years and older. Second, benzodiazepines were most often prescribed for anxiety-related complaints across all age groups, although use for insomnia became more common with increasing patient age. Third, sociodemographic factors appeared to influence whether patients received these medications. Finally, approximately 40% of adults prescribed a benzodiazepine also received other CNS depressants, and this co-prescribing became more common with older age, psychological distress, and poorer overall health.

Despite a recent rise in psychological distress,30 anxiety, and depression31 among US adults during the COVID-19 pandemic, the percentage of adults treated with benzodiazepines decreased. This decline was related mainly to reduced use by adults aged 56 and older, although the underlying reasons remain unclear. Following the 2012 American Geriatrics Society recommendation to avoid benzodiazepines in older adults for insomnia, agitation, or delirium, and limit use in anxiety,32 interest grew in educational programs for patients and physicians that promote therapeutic alternatives to benzodiazepines in this population.33 More recently, in 2022, the National Committee for Quality Assurance proposed a quality measure focused on deprescribing benzodiazepines in older adults.34 It is also possible that the rise of telemedicine during the COVID-19 pandemic35; the complexities of telehealth prescribing of controlled substances, especially across state lines36; and the FDA’s 2020 black box warning concerning benzodiazepine misuse37 also contributed to the recent decline in benzodiazepine prescribing.

The finding that most benzodiazepine treatment was short-term and aimed at relieving anxiety indicates that clinicians generally follow clinical guidelines,38,39 which assume that long-term use leads to tolerance, dose escalation, and higher risk of adverse effects compared with antidepressants. However, empirical evidence suggests that long-term benzodiazepine use typically does not lead to dose escalation9 and that benzodiazepines may not involve a higher burden of adverse effects40 or a greater risk of falls41 than antidepressants.

Over half of adults who received benzodiazepines also received antidepressants which are effective for anxiety disorders.42 Because nearly two-thirds of adults treated with benzodiazepines received them for stress or anxiety disorders, the frequent use of antidepressants by adults treated with benzodiazepines suggests that prescribing physicians were aware that antidepressants are effective for common anxiety disorders. For adults with generalized anxiety disorder, for example, combined use of benzodiazepines and antidepressants during the first few weeks is recommended, followed by tapering of benzodiazepines and continuing antidepressant treatment.43 In line with the basic epidemiology of insomnia,44 use of benzodiazepines for insomnia increased with patient age.

Several sociodemographic characteristics were related to use of prescription benzodiazepines. A socioeconomic gradient in benzodiazepine use was observed with greater use among adults with lower incomes, public insurance, and rural residence and among those who were nonemployed compared to those with higher incomes, private insurance, and urban residence and who were employed. Yet, benzodiazepine use among white non-Hispanic adults was more than twice as high than among other racial and ethnic groups. Further research is needed to probe the underlying causes of these patterns. Some potential contributing factors include differential exposure to stressors,45 inadequate access to nonpharmacological interventions such as cognitive behavioral therapy for insomnia,46 a lack of risk awareness,47 and a potential for variation in physician readiness to prescribe benzodiazepines when indicated to racial and ethnic minorities.48

Some patients with anxiety may prefer benzodiazepines over antidepressants due to their faster onset of action and ability to be taken only as needed. For other patients, benzodiazepines may be used as an augmentation strategy for disorders that do not remit solely with antidepressants or they may be prescribed to patients who have experienced sexual or other adverse effects from antidepressants. A recent meta-analysis revealed that benzodiazepines were significantly more effective than antidepressants for somatic and psychic symptoms of generalized anxiety disorder, though only the analysis of somatic symptoms reached statistical significance.49

Approximately 4 in 10 adults prescribed benzodiazepines were also prescribed other CNS depressants during the same year. Concurrent use of benzodiazepines and other CNS depressants has been associated with falls50 and overdoses.51 Because these medications are prescribed for variable time periods, fewer than 4 in 10 benzodiazepine treated adults likely had concurrent use of other CNS depressants. Nevertheless, the observed patterns can help orient clinicians to patient groups at elevated risk of concurrent use including adults aged 36–55 years and ≥56 years, women, individuals with higher levels of psychological distress, and people with worse general health.

Although we anticipated rising risk of receiving benzodiazepines and other CNS depressants with increasing age, there was little difference in the percentage of adults aged 36–55 years and ≥56 years who were prescribed both medications. The age and sex patterns may be related to females and older adults more often than males and younger adults seeking medical care or reporting chronic pain.52 The associations of using both medication groups with psychological distress and poor general health likely reflect underlying psychiatric and general medical conditions for which CNS-depressant medications are prescribed.

When evaluating the safety of benzodiazepines, it is important to distinguish between nonprescribed use, which is closely associated with compulsive or uncontrolled use, and prescribed use, which carries much lower risk.53 MEPS can only measure prescriptions fills and does not capture how the medication is used. Nonetheless, large observational studies have reported that prescribed benzodiazepines are associated with an increased risk of developing substance use problems or disorders relative to untreated controls54–56 and patients receiving comparator medications.57

This analysis has several limitations. First, the MEPS, which is a household-reported survey, relies on the respondent’s willingness and ability to accurately report medication use, and so reporting bias could result in underestimation of benzodiazepine use and misattribution of the reason for use. Second, although the MEPS uses probability-based sampling, statistical adjustments for nonresponse may not eliminate nonresponse bias. Third, statistical power was limited in some subgroups, resulting in wide confidence intervals and some unreliable estimates. Fourth, prescription of benzodiazepines and other CNS-depressant medications in the same year does not necessarily denote contemporaneous coprescription. Fifth, information was not available throughout the study period on whether prescriptions were from office-based or telemedicine visits. Finally, information was not available concerning the medical specialty of those prescribing benzodiazepines, benzodiazepine dose, or nonmedical benzodiazepine use.

Between 2018 and 2022, there was a decrease in the prescription of benzodiazepines to US adults, especially to adults aged ≥56 years. This occurred during a period of rising psychological distress and mental health treatment,30 indicating that the role of benzodiazepines is diminishing in US outpatient mental health care. Yet, because many adults who received benzodiazepines were also treated with opioids and other CNS depressants, there is a continuing need for close clinical follow-up and careful assessment for drug-drug adverse effects.

Article Information

Published Online: February 18, 2026. https://doi.org/10.4088/JCP.25m16125

© 2026 Physicians Postgraduate Press, Inc.

Submitted: September 2, 2025; accepted December 15, 2025.

To Cite: Olfson M, McClellan C, Zuvekas SH, et al. Trends in benzodiazepine prescribing to adults in the United States: results from the Medical Expenditure Panel Survey. J Clin Psychiatry 2026;87(1):25m16125.

Author Affiliations: Department of Psychiatry, Vagelos College of Physicians and Surgeons, Columbia University, New York, New York (Olfson); Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality, Rockville, Maryland (McClellan, Zuvekas); National Institute on Drug Abuse, Bethesda, Maryland (Blanco).

Corresponding Author: Mark Olfson, MD, MPH, Department of Psychiatry, Vagelos College of Physicians and Surgeons of Columbia University, 1051 Riverside Drive, New York, NY ([email protected]).

Relevant Financial Relationships: None of the authors report conflicts of interest.

Funding/Support: None.

Disclaimer: The views expressed in this paper are those of the authors, and no official endorsement by the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality or the U.S.

Department of Health and Human Services is intended or should be inferred.

Supplementary Material: Available at Psychiatrist.com.

Clinical Points

- Benzodiazepine prescriptions in the US declined from 2018 to 2022, especially for adults 56 years and older, suggesting more cautious prescribing.

- Before initiating a benzodiazepine, physicians should check the patient’s medication list for potential drug-drug interactions involving other CNS depressants.

- These clinical considerations appear to be particularly relevant for patients in poor health and those with serious psychological distress.

References (57)

- Riemann D, Espie CA, Altena E, et al. The European Insomnia Guideline: an update on the diagnosis and treatment of insomnia 2023. J Sleep Res. 2023;32(6):e14035. PubMed CrossRef

- Balon R, Starcevic V. Role of benzodiazepines in anxiety disorders. Adv Exper Med Biol. 2020;1191:367–388. PubMed CrossRef

- Kast KA, Sidelnik SA, Nejad SH, et al. Management of alcohol withdrawal syndromes in general hospital settings. BMJ. 2025;388:e080461. PubMed CrossRef

- Hirjak D, Rogers JP, Wolf RC, et al. Catatonia. Nat Rev. Dis Prim. 2024;10(1):49. PubMed CrossRef

- Penovich PE, Rao VR, Long L, et al. Benzodiazepines for the treatment of seizure clusters. CNS Drugs. 2024;38(2):125–140. PubMed CrossRef

- Ogawa Y, Takeshima N, Hayasaka Y, et al. Antidepressants plus benzodiazepines for adults with major depression. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2019;6(6):CD001026. PubMed CrossRef

- Soumerai SB, Simoni-Wastila L, Singer C, et al. Lack of relationship between long-term use of benzodiazepines and escalation to high dosages. Psychiatr Serv. 2003;54(7):1006–1011. PubMed CrossRef

- Alessi-Severini S, Bolton JM, Enns MW, et al. Sustained use of benzodiazepines and escalation to high doses in a Canadian population. Psychiatr Serv. 2016;67(9):1012–1018. PubMed CrossRef

- Rosenqvist TW, Wium-Andersen MK, Wium-Andersen IK, et al. Long-term use of benzodiazepines and benzodiazepine-related drugs: a register-based Danish cohort study on determinants and risk of dose escalation. Am J Psychiatry. 2024;181(3):246–254. PubMed CrossRef

- Maust DT, Lin LA, Blow FC. Benzodiazepine use and misuse among adults in the United States. Psychiatr Serv. 2019;70(2):97–106. PubMed CrossRef

- Dokkedal-Silva V, Galduroz JCF, Tufik S, et al. Neural and functional connectivity changes caused by long-term use of benzodiazepines: investigating the mechanisms of tolerance and dependence. Sleep Med. 2023;104:1–2. PubMed CrossRef

- Jobert A, Laforgue EJ, Grall-Bronniec M, et al. Benzodiazepine withdrawal in older people: what is the prevalence, what are the signs, and which patients? Europ J Clin Pharmacol. 2021;77:171–177.

- Na I, Seo J, Park E, et al. Risk of falls associated with long-acting benzodiazepines or tricyclic antidepressants use in community-dwelling older adults: a nationwide population-based case-crossover study. Int J Env Res Pub Health. 2022;19(14):8564. PubMed CrossRef

- Dassanayake T, Michie P, Carter G, et al. Effects of benzodiazepines, antidepressants and opioids on driving: a systematic review and meta-analysis of epidemiological and experimental evidence. Drug Saf. 2011;34(2):125–156. PubMed CrossRef

- Teverovsky EG, Gildengers A, Ran X, et al. Benzodiazepine use and risk of incident MCI and dementia in a community sample. Int Psychogeriatrics. 2024;36(2):142–148. PubMed CrossRef

- Liu S, O’Donnell J, Gladden RM, et al. Trends in nonfatal and fatal overdoses involving benzodiazepines—38 states and the District of Columbia, 2019-2020. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2021;70(34):1136–1141. CrossRef

- Kleinman RA, Weiss RD. Benzodiazepine-involved overdose deaths in the USA: 2000–2019. JGIM. 2022;37(8):2103–2109. PubMed CrossRef

- Soejima K, Sato H, Hisaka A. Age-related change in hepatic clearance inferred from multiple population pharmacokinetic studies: comparison with renal clearance and their associations with organ weight and blood flow. Clin Pharmacokinet. 2022;61(2):295–305. PubMed CrossRef

- Greenblatt DJ, Harmatz JS, Shader RI. Diazepam in the elderly: looking back, ahead and at the evidence. J Clin Psychopharmacol. 2020;40(3):215–219. PubMed CrossRef

- Samuel MJ. American Geriatrics Society 2023 updated AGS Beers Criteria® for potentially inappropriate medication use in older adults. J Am Ger Soc. 2023;71(7):2052–2081. CrossRef

- Sun EC, Dixit A, Humphreys K, et al. Association between concurrent use of prescription opioids and benzodiazepines and overdose: retrospective analysis. BMJ. 2017;356:760. PubMed CrossRef

- Agarwal SD, Landon BE. Patterns in outpatient benzodiazepine prescribing in the United States. JAMA Netw Open. 2019;2(1):e18799.

- Olfson M, King M, Schoenbaum M. Benzodiazepine use in the United States. JAMA Psychiatry. 2015;72(2):136–142. PubMed CrossRef

- Morin L, Johnell K, Laroche ML, et al. The epidemiology of polypharmacy in older adults: register-based prospective cohort study. Clin Epidemiol. 2018;10:289–298. PubMed CrossRef

- Bachhuber MA, Hennessy S, Cunningham CO, et al. Increasing benzodiazepine prescriptions and overdose mortality in the United States, 1996-2013. Am J Public Health. 2016;106(4):686–688. PubMed CrossRef

- Chowdury S. MEPS HC-036BRR: 1996–2019 Replicate File for BRR Variance Estimation; Rockville, MD; Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality. Center for Financing, Access, and Cost Trends; 2021. https://meps.ahrq.gov/data_stats/download_data/pufs/h036brr/h36brr19doc.shtml

- US Food and Drug Administration. FDA Drug Safety Communication: FDA warns about serious risks and death when combining opioid pain or cough medicines with benzodiazepines; requires its strongest warning. https://www.fda.gov/drugs/drug-safety-and-availability/fda-drug-safety-communication-fda-warns-about-serious-risks-and-death-when-combining-opioid-pain-or

- Kessler RC, Barker PR, Colpe LJ, et al. Screening for serious mental illness in the general population. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2003;60(2):184–189. PubMed CrossRef

- Office of the Assistant Secretary for Planning and Evaluation. Poverty Guidelines. https://aspe.hhs.gov/topics/poverty-economic-mobility/poverty-guidelines

- Olfson M, McClellan C, Zuvekas SH, et al. Trends in psychological distress and outpatient mental health care of adults during the COVD-19 era. Ann Int Med. 2024;177(3):353–362. PubMed CrossRef

- Vahratian A, Blumberg SJ, Terlizzi EP, et al. SchillerJS. Symptoms of anxiety or depressive disorder and use of mental health care among adults during the COVID-19 pandemic—United States. Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2021;70(13):490–494. PubMed CrossRef

- American Geriatrics Society Updated Beers Criteria for Potentially Inappropriate Medication Use in Older Adults. J Am Ger Soc 2012;60(4):616–631.

- McEvoy AM, Langford AV, Liau SJ, et al. Deprescribing benzodiazepine receptor agonists in older adults and people with cognitive impairment: a systematic review. J Am Ger Soc. 2025;73(9):2905–2913. PubMed CrossRef

- National Committee on Quality Assurance. Deprescribing of Benzodiazepines in Older Adults (DBO). https://www.ncqa.org/report-cards/health-plans/state-of-health-care-quality-report/deprescribing-of-benzodiazepines-in-older-adults-dbo

- McBain RK, Schuler MS, Qureshi N, et al. Expansion of telehealth availability for mental health care after state-level policy changes from 2019 to 2022. JAMA Netw Open. 2023;6(6):e2318045. PubMed CrossRef

- Drug Enforcement Administration. DEA announces three new telemedicine rules that continue to open access to telehealth treatment while protecting patients. https://www.dea.gov/press-releases/2025/01/16/dea-announces-three-new-telemedicine-rules-continue-open-access

- United States Food & Drug Administration. FDA requiring Boxed Warning updated to improve safe use of benzodiazepine drug class. https://www.fda.gov/drugs/drug-safety-and-availability/fda-requiring-boxed-warning-updated-improve-safe-use-benzodiazepine-drug-class

- American Academy of Family Physicians. Practice guideline: de-prescribing benzodiazepine receptor agonists for insomnia. Am Fam Physician. 2019;99(1):58–59.

- Scottish Government. Quality prescribing for benzodiazepines and z-drugs: guide for improvement 2024 to 2027. https://www.gov.scot/publications/quality-prescribing-benzodiazepines-z-drugs-guide-improvement-2024-2027

- Quagliato KA, Flammetta C, Shader RL, et al. Selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors and benzodiazepines in panic disorder: a meta-analysis of common side effects in acute treatment. J Psychopharmacol. 2019;33(11):1340–1351. PubMed

- Woolcott JC, Richardson KJ, Wiens MO, et al. Meta-analysis of the impact of 9 medication classes on falls in elderly persons. Arch Intern Med. 2009;169(21):1952–1960. PubMed CrossRef

- Kopcalic K, Arcaro J, Pinto A, et al. Antidepressants versus placebo for generalised anxiety disorder (GAD). Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2025.

- Gomez AF, Barthel AL, Hofman SG. Comparing the efficacy of benzodiazepines and serotonergic anti-depressants for adults with generalized anxiety disorder: meta-analytic review. Curr Opin Pharmacotherp. 2019;8:883–894.

- Brewster GS, Riegel B, Gehrman PR. Insomnia in the older adult. Sleep Med Clin. 2022;17(2):233–239. PubMed CrossRef

- McEwen BS, Gianaros PJ. Central role of the brain in stress and adaptation: links to socioeconomic status, health, and disease. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2010;1186:190–222. PubMed CrossRef

- Koffel E, Bramoweth AD, Ulmer CS. Increasing access to and utilization of cognitive behavioral therapy for insomnia (CBT-I): a narrative review. J Gen Intern Med. 2018;33(6):955–962. PubMed CrossRef

- Sake F, Wong K, Bartlett DJ, et al. Benzodiazepine use risk: understanding patient specific risk perceptions and medication beliefs. Res Soc Adm Pharm. 2019;15(11):1317–1325. PubMed CrossRef

- Cook B, Creedon T, Wang Y, et al. Examining racial/ethnic differences in patterns of benzodiazepine prescription and misuse. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2018;187:29–34. PubMed CrossRef

- Beyer C, Currin CB, Williams T, et al. Meta-analysis of the comparative efficacy of benzodiazepines and antidepressants for psychic versus somatic symptoms of generalized anxiety disorder. Comp Psych. 2024;132:152479. PubMed CrossRef

- Nurminen J, Puustinen J, Piirtola M, et al. Opioids, antiepileptic and anticholinergic drugs and the risk of fractures in patients 65 years of age and older: a prospective population-based study. Age Ageing. 2013;42(3):318–324. PubMed CrossRef

- Sun EC, Dixit A, Humphreys K, et al. Association between concurrent use of prescription opioids and benzodiazepines and overdose: retrospective analysis. BMJ. 2017;356:j760. PubMed CrossRef

- Lucas JW, Sohi I. Chronic pain and high-impact chronic pain in U.S. adults, 2023. NCHS Data Brief, no 518. National Center for Health Statistics; 2024.

- O’Brien CP. Benzodiazepine use, abuse, and dependence. J Clin Psych. 2005;66:(suppl2)28–33.

- Wang X, Chang Z, Molero Y, et al. Incident benzodiazepine and z-drug use and subsequent risk of alcohol-and drug-related problems: a nationwide matched cohort study with co-twin comparison. J Psychopharmacol. 2025;1:2698811251373069. PubMed CrossRef

- Sun CG, Pola AS, Su KP, et al. Benzodiazepine use for anxiety disorders is associated with increased long-term risk of mood and substance use disorders: a large-scale retrospective cohort study. Drug Alc Depend Rep. 2024;12:100270. CrossRef

- McCabe SE, Schulenberg JE, Wilens TE, et al, Transitions in prescription benzodiazepine use and misuse and in substance use disorder symptoms through age 50. Psych Serv 2023;74(11), 749110.

- Bushnell GA, Gerhard T, Keyes K, et al. Association of benzodiazepine treatment for sleep disorders with drug overdose risk among young people. JAMA Netw Open. 2022;5(11):e2243215. PubMed CrossRef

Enjoy this premium PDF as part of your membership benefits!