Abstract

Objective: To provide recommendations for creating and sustaining a treatment-resistant depression (TRD) consultation program at an academic health center. This is a complementary manuscript to Part II, which discusses critical elements of the assessment package for such subspecialized consultations.

Participants: Participants were a working group of 12 clinicians, researchers, administrators, and patient advocates from the National Network of Depression Centers (NNDC) TRD Task Group.

Evidence: The recommendations are based on expert opinion. TRD consultation programs can offer an individualized treatment roadmap to be implemented by the patient and their providers with the goal of maximizing the likelihood of response or full remission of symptoms. However, there is currently no published work addressing the practical and logistical considerations for establishing such programs. This consensus statement puts forth a set of recommendations that could serve as a basis for future empirical work.

Consensus Process: Members of the working group provided written descriptions of relevant procedures used at their institutions, which were used during a day-long in-person forum to achieve consensus on recommendations for each major aspect of a TRD consultation program. Subgroups were formed to draft recommendations, and points of disagreement were resolved at subsequent meetings of the full working group.

Conclusions: We describe key practical considerations, including systems-level and financial issues; equity and access to TRD care for a diverse patient population; selecting a target population and facilitating the referral process; the product of the consultation; communication between the program, patient, and community providers; and postconsultation care and contact.

J Clin Psychiatry 2025;86(2):24cs15335

Author affiliations are listed at the end of this article.

See part II by Fournier et al

Depression is a major public health concern and is among the most disabling of illnesses in medicine, affecting an estimated 300 million people across the globe.1 The physiological and psychosocial disruptions produced by depression and other mood disorders are associated with many negative outcomes including unemployment, deteriorating health, premature mortality, and death by suicide.1 In the United States, the prevalence of depression has increased in recent years due to the COVID-19 pandemic and the ensuing economic instability.2,3 Although effective treatments are available for depression, many individuals do not respond sufficiently, even after multiple antidepressant trials. When two or more adequately conducted therapeutic trials of evidence-based treatments fail to treat depressive symptoms to the point of response, the depressive episode can be labeled as “treatment-resistant depression,” or TRD.4,5 Approximately 30% of individuals who are diagnosed with major depressive disorder will eventually meet the criteria for TRD,4,6 making it a highly prevalent mental health problem. The prevalence of TRD is even higher for people with bipolar disorders7 and when the definition of TRD considers failure to achieve sustained remission of depressive symptoms.8,9 TRD is associated with disproportionately high healthcare costs and unemployment, leading to a substantial economic burden estimated at $43.8 billion in the US alone.10

Patients with TRD and a history of multiple treatment trials may benefit from subspecialty consultation. At a systems level, this has spurred the development of specialized clinics to assess TRD. Specialized mental health clinics arise from a variety of factors, including increasing awareness of the complexity of mental illness, advances in neuroscience and treatment sophistication, and a growing demand for specialized services from patients and healthcare systems.11 The trend toward greater subspecialization within psychiatry mirrors a general pattern within medicine overall.11–13

Specialized clinics, some of which are branded as “centers of excellence,” have been established for nearly all fields of medicine.14,15 At present, the foundational characteristics that should define “centers of excellence” are still unclear, and there is a lack of clarity as to how these characteristics may differ from conventional “institutes” or “centers.”16 Further, the application of these terms varies widely among institutions. Regardless of the terminology, specialized clinics serve important functions such as diagnosis and formulation, recommending (and sometimes initiating) specific treatments, driving research, and providing optimized training opportunities to address the needs of people with especially complex presentations for which additional opinions are sought or are uncommon, and sometimes resource-intensive clinical evaluations and services are needed.17,18 Additionally, specialized clinics are themselves increasingly organized into collaborative networks19 such as the National Network of Depression Centers (NNDC),20 thus mobilizing cross-institutional collaborative resources and expertise. The authors of this article form the majority of the Treatment Resistant Depression Task Group of the NNDC and represent multiple leading depression centers across the United States. Many of these centers include a consultation program for patients with TRD.

TRD consultation programs can play an important role in improving treatment outcomes by providing access to subspecialists with advanced training and experience in mood disorders and incorporating innovative technologies and tools that help improve diagnostic precision and tailor treatment strategies to individual patients. These consultations can offer a treatment roadmap to be implemented by the patient and their mental health providers with the goal of maximizing the likelihood of response or full remission of symptoms. TRD consultations can represent either one-time encounters or a broader treatment program, the latter often affiliated with an academic medical center.

This article presents the consensus of the NNDC TRD Task Group on the key aspects of starting and maintaining a TRD consultation program at an academic health center, and we offer recommendations for future research. In the following sections, we describe several key considerations in creating and sustaining such a consultation program: (a) engaging all stakeholders at the systems level, (b) addressing equity, (c) identifying the target population, (d) creating an efficient referral process, (e) defining the product of the consultation, including recommendations on how to communicate the results of the consultation in a clear way to both the patient and the clinician, and (f) delineating the conditions for postassessment contact. In our opinion, the question of what constitutes a best-practice comprehensive TRD evaluation deserves special consideration, which we discuss in a separate (Part II) manuscript21 accompanying this report.

SYSTEMS-LEVEL CONSIDERATIONS

The process of developing a TRD consultation program should include all relevant organizational stakeholders, including the hospital system, administration, the business development office, billing and financial departments, and departments (or divisions) of psychiatry and psychology. It is often the case that new clinical programs are initiated and championed by clinicians who, as a group, are most likely to identify and adopt innovative assessment and treatment strategies for refractory disorders.22 Consequently, clinicians are typically involved in every stage of the program development process and often bear the burden of educating the administration and the business and operations decision-makers about the purposes of the proposed clinic and its “added value” to the patient, the host department, and the organization as a whole.

When initiating a new clinical service, it is reasonable to anticipate a certain amount of organizational “red tape” and financial challenges. One should be prepared to answer questions related to start-up costs, who will cover those costs, and the anticipated timeline for financial sustainability. A feasibility review aimed at assessing the financial viability of the proposed program is an essential element of building a solid business case. A business model for the TRD consultation program should include an inventory of all types of anticipated expenses, including projections of costs associated with dedicated personnel time, diagnostics (eg, laboratory tests, diagnostic procedures, etc., as indicated), clinical referrals (as indicated), the physical space, and overhead costs. Cost modeling might also include any expenses related to marketing within and outside the host health organization. Cost and revenue estimates should be based on a patient flow projection for the year. Income projections should include both direct and indirect proceeds. Direct proceeds are the billings for the specific services and procedures administered in the context of a TRD consultation and are influenced by the payor mix. Indirect proceeds, if applicable to the setting, capture the projected added revenue generated through affiliated interventional services, such as partial hospitalization or intensive outpatient programs, neuromodulatory interventions (eg, electroconvulsive therapy, transcranial magnetic stimulation, and other), nonconventional antidepressant treatments (eg, ketamine infusions, esketamine administration, etc.), and other therapeutics, as well as industry-sponsored clinical trials. Even though these calculations would be approximated, they are often necessary to reassure organizational stakeholders that the proposed program would be financially sustainable and produce a return on investment.

Providers involved in specialized TRD services may benefit from a consultation with coding/billing specialists at their institution to ensure that they bill accordingly for complex services. Fiscal efficiency of the business model for the consultation clinic could be enhanced by positioning each of the relevant personnel to function “at the top of their license.” For example, a licensed clinical social worker or registered nurse could serve as intake coordinator and could review previous medical histories and highlight most relevant portions for the doctoral-level clinicians. A licensed psychologist can perform the clinical interview in addition to the relevant psychological testing. The psychiatrist’s clinical interview can build on the background information gathered by the psychologist and save time for a more detailed focus on medical history, potential medical comorbidities, differential diagnoses, and past medication and somatic treatment trials. In addition, delegating portions of the assessment process to advanced-practice clinicians or appropriate trainees (eg, psychology interns or postdocs, pharmacy students, and psychiatry residents or fellows) can optimize cost savings while contributing to the educational mission of the organization.

A related consideration when developing a new TRD consultation program, particularly if tied to internal referral sources and treatment service lines, is to build the infrastructure to ensure that appropriate data are collected to evaluate the success of the program. These data can be used for quality improvement projects and to demonstrate the added revenue that the consultation program brings into the system. At academic institutions, these data could also be used to support scientific work, and the data-collection infrastructure could be used to support future internally or externally funded clinical trials and observational studies. In developing this infrastructure, it is helpful to partner early on with Information Technology and Research Information Technology departments to ensure that the specific data elements most relevant to the particular setting can be readily extracted.

EQUITY

Accessibility is a critical component of building a clinic that successfully serves the community while facilitating clinical intervention research that is generalizable. In some settings, increasing the accessibility of care for patients with financial and geographic challenges may seem to conflict with “selling” a program to administration who are concerned with costs. However, it is critical to recognize that communities with limited access often reflect the patient populations most in need of care, that treating those patients serves to increase the public health impact of clinic funding, and that doing so will likely increase the rigor and reproducibility of any associated TRD intervention research.

Patient access to TRD intervention is hindered by multiple issues. These include but are not limited to (a) insurance coverage, (b) geography and proximity of services to communities in need, (c) citizenship/ documentation concerns of immigrant or migrant communities, (d) basic accessibility services and transportation, (e) language barriers, (f) mistrust in the healthcare system, and (g) mental health stigma.23–27 Unfortunately, these issues are not mutually exclusive and can compound the difficulties in patient access.

The TRD consultation referral process itself may present a significant barrier to care. Some TRD clinics require referrals to come through a psychiatrist or psychologist. While this does help with the triage process (see below) by increasing the proportion of appropriate referrals, it limits access for the large population of patients whose depression is treated by primary care or psychiatric advanced practice registered nurses /physician assistants. These patients are often unable to access psychiatrists or psychologists due to the significant workforce shortage in most counties in the US.28 A related critical question that consultation clinics will need to answer is whether they are able to accommodate self-referrals. An important factor in accepting any referral is ensuring either that the patient has an ongoing relationship with practitioners who will continue to care for the patient after the TRD consultation process is ended or that the clinic is part of a larger treatment program that can accommodate patients who need to establish care.

There are several reasons to anticipate accessibility issues. Institutions with resources (ie, universities and medical schools) may be located within affluent geographical areas with homogeneous cultural and socioeconomic characteristics. Institutional and legislative funding for a clinic is often intended to serve the broader community, but, in reality, only patients in the community with insurance coverage, good geographical access, and transportation resources have the means to access care. Furthermore, providers and care coordinators often reflect the demographics of those with easy access to care and do not reflect the communities for which services are more out of reach.29 Given these concerns, it may be important to establish regular communication with clinics and social support organizations in underserved communities. These clinics can provide information about billing and community outreach that can inform efforts to reduce costs for patients in need. Communication with these clinics also allows for education about TRD, treatment options, and the expected costs and benefits of interventions. Such relationships could also help those championing the development of the TRD interventions to understand community members’ perceptions and concerns about TRD and its treatment, assisting in the effort to eliminate stigma. Hiring staff and providers who reflect the demographics of the broader community, including those who are bilingual, may positively impact this process and facilitate trust. Finally, creating strategies for patient access to the TRD clinic from multiple areas, by public transportation or community services, may improve access. These strategies do require upfront work and financial investment; however, they also hold promise for increasing the impact and research rigor of the program, and they can open doors to new avenues for research and clinic funding.

The rapid expansion of telemedicine in psychiatry spurred by the COVID-19 pandemic has resulted in overall increased access to care by lowering barriers related to geography, transportation, and stigma, despite technological barriers that continue to limit access for some patients.30–32 There is growing evidence that psychiatric treatment via telehealth is no less effective than in-person care.31–33 Psychiatric diagnosis via telehealth is less studied but does show promise.34 Due to the limited evidence for telehealth in diagnosis, and the complexity of patients seen in TRD consultation, we recommend in-person consultations, if feasible, while supporting the use of telehealth for patients who cannot access in-person care.

TARGET POPULATION

A critical step in establishing any subspecialty consultation program is defining the patient population clearly. In these recommendations, we include a broad population of patients aged 18 years or older with diagnosed unipolar or bipolar depression of any duration. As there are several published definitions of TRD,4 each with some degree of support, we do not typically require that patients’ illnesses or treatment histories meet specific criteria for any particular diagnosis or definition of TRD. We do, however, recommend that clinics exclude patients who are treatment-naive (ie, have not had a trial of any biological or psychological intervention). Some level of stability of the current psychiatric illness is also necessary for consultations to be most helpful; we do not recommend performing consultations during an acute psychiatric crisis, but rather to refer patients to a higher level of care until acute safety concerns have been addressed. Patients seen in TRD consultation clinics have typically been diagnosed by an outside practitioner with “depression” of some variety, often with comorbid psychiatric and medical diagnoses. Parsing the complexity of the patient’s condition is an important part of TRD consultation, and the diagnostic assessment is meant to clarify the nature of the patient’s depression in the context of their comorbid conditions and psychosocial milieu.

REFERRAL PROCESS

Patients will typically be referred for TRD consultation by an outside practitioner who has established a working diagnosis of a unipolar or bipolar depressive episode. As noted above, some consultation clinics may also accept self-referrals from patients or families. Regardless of the referral source, a TRD consultation program requires a referral process that includes screening and triage; gathering outside assessment and treatment records from physicians, psychotherapists, other clinicians, and pharmacies; and obtaining completed patient-generated information filled out by a patient or a surrogate prior to the first visit. Many centers have a standardized information and instrument packet that is electronically or mail-delivered to patients and must be filled out and returned prior to scheduling a visit. Requesting, receiving, and organizing these documents for all patients referred to the clinic is a time-consuming process. Our centers that have a designated office staff member serving as Intake Coordinator have found that the process is much more cost- and time-efficient, allowing valuable clinician time to be spent reviewing the collated, organized records and evaluating the patients. Many of us have found that training a clinic nurse to function as Intake Coordinator works particularly well due to their existing knowledge of depression and common treatments; this person typically also has other clinical duties for budgetary reasons. In consultation programs with sufficient funding, the Intake Coordinator role can expand to include providing patients with appointment assistance and prior authorization information. This “Healthcare Navigator” role can enhance patient care and communication and be a reassuring presence in an often-labyrinthine healthcare system.

In the screening and triage process, some referrals will not be appropriate due to acuity or treatment naivete (see Target Population above) or lack of active mood disorder diagnosis. In this case, the Intake Coordinator would contact the referral source (provider or patient/ family) and offer a list of more appropriate venues to obtain care. As discussed in the Equity section above, it is often helpful for TRD consultation clinic staff to have a working knowledge of available mental health resources in the surrounding community.

PRODUCT OF THE CONSULTATION

The ultimate purpose of assessment is to guide effective treatment. Accurate assessment is important across all psychiatric settings but is particularly vital in the context of a TRD consultation clinic. Patients presenting to these clinics have typically attempted several prior treatments that have not been adequately effective. Given the high morbidity and mortality associated with TRD, it is critical that assessments in these clinics (1) clarify and confirm the nature of the patient’s illness, (2) identify the patient’s goals for treatment, and (3) ultimately help to determine which intervention is most likely to be effective for this particular patient at this specific time. The details of such an assessment process are beyond the scope of this paper, and we dedicate a separate review to TRD assessment considerations (for this review, see Part II: Patient Assessment and Evaluation21).

The diagnostic impression and treatment recommendations are the end products of the TRD consultation. These sections of the consultative report will often be the most anticipated and most scrutinized by referring clinicians and patients. Therefore, the diagnostic impression and treatment recommendations must be clearly communicated at an appropriate level of detail, depending on the referral question(s) asked and the types of individuals who will use the information in the report. The latter may be a referring psychiatrist (who may only require an outline of suggested treatment approaches to consider) or a primary care clinician (who may appreciate more detailed guidelines on starting or optimizing specific next-step treatments).35

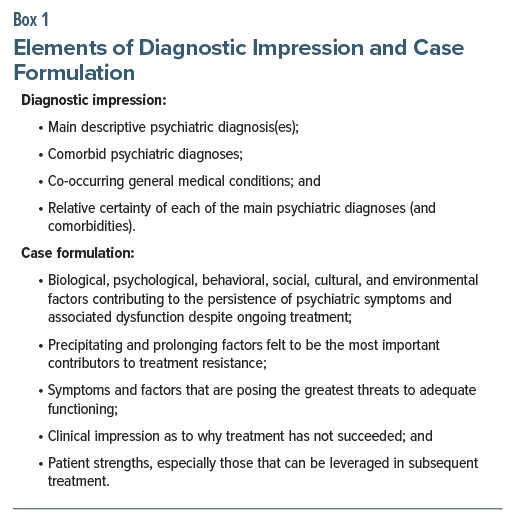

The diagnostic impression section of the report should contain the patient’s descriptive psychiatric and general medical diagnoses and a case formulation—that is, an explanatory model incorporating biological, psychological, and social/environmental factors and stressors that are helping maintain the patient’s depressive symptoms despite reasonable efforts at treatment,36–41 as well the patient’s strengths and available resources that contribute to coping and resilience. The case formulation should also emphasize any gaps between clinical needs and the treatments that have been trialed up to the point of referral.42,43 These elements should be discussed, if possible, with the patient at the conclusion of the evaluation. We recommend that the feedback be structured to include, at a minimum, the points listed in Box 1.

Because standard approaches to treatment may not sufficiently address the complex needs of individual patients with TRD, the treatment recommendations provided at the end of the consultation should stem primarily from the case formulation.44,45 The descriptive diagnoses, including the main diagnoses with relevant illness subtypes, can yield a range of evidence-supported therapeutic options. The list of options can be narrowed based on other descriptive factors such as the patient’s co-occurring psychiatric and general medical conditions. However, the case formulation may be the most useful tool for individualizing treatment decisions because it provides both a conceptual model for why a given patient’s depression has been so difficult to treat and a means of prioritizing reasonable treatment options according to the specific needs and preferences of the patient.46,47

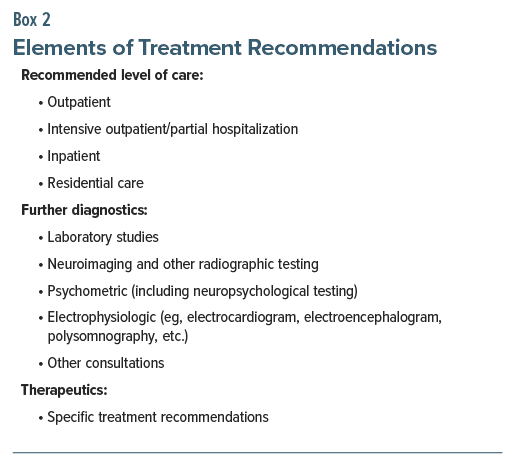

To ensure that treatment recommendations are as clear and as systematic as possible, we recommend that the specific recommendations be nested within broad categories of information. These categories include but need not be limited to ones listed in Box 2.

Concerning level of care, the diagnostic and treatment recommendations provided by the consultant, in most cases, can be capably executed in an outpatient setting. For others, a higher level of care will need to be considered, especially if safety considerations warrant it or if the clinical needs of the patient or the complexities of treatment recommendations require greater levels of structure, supervision, or monitoring than can be provided in traditional outpatient settings. These may include advising voluntary admission to a long-term or intensive specialized inpatient, hospital-based outpatient, or other structured outpatient program for TRD.48 If a higher level of care than the outpatient setting is recommended, this advice should be explicitly reviewed with patients and referring clinicians, including the rationale for such recommendations.

Regarding diagnostics, a detailed discussion of what further tests should be considered—either routinely for all patients with difficult-to-treat depression or in specific cases—is beyond the scope of this section and is the focus of the Part II companion manuscript to this paper. Instead, we suggest the systematic consideration of blood and urine-based testing; electrophysiological, neuroimaging, and other radiographic testing as indicated; psychometric or neuropsychological testing as indicated; and other consultations that may be needed to prioritize specific treatments and identify factors that may contribute to a given patient’s treatment resistance.49 These considerations will also help add structure to the feedback provided to the patient, caregivers, and referring clinicians pertaining to recommended diagnostic tests for the specific case, with an accompanying rationale.

Finally, therapeutic recommendations should include, at a minimum, a clear delineation of immediate next steps. To maximize the value of the consultation, however, several sequentially ordered recommendations should be considered. In doing so, a “care pathway” is created with each subsequent step activated by lack of adequate response or intolerance to the preceding step. In our experience, providing sequentially ordered treatment considerations are preferred by referring clinicians over simply listing options to consider. In some cases, each major step can contain “substeps,” for instance, when discussing how partial responses can be addressed (eg, by modifying the dose of medication(s), adding psychotherapy, pharmacologic augmentation, or some other combination thereof).50 For treatment recommendations, the full spectrum of interventions should be considered, including psychotherapy, pharmacotherapy, neuromodulation, chronotherapeutics, and lifestyle medicine interventions.51–56 The need to address existing medical comorbidities that may be affecting symptoms should be explicitly stated. Whenever appropriate, treatments to avoid or those considered to be low priority should be called out as such with a rationale for doing so. Examples of the latter include potentially dangerous drug-drug interactions, incompatibility with a patient’s age or general medical conditions, and limited evidence for use in TRD. Additionally, treatment recommendations may include the application of measurement-based care (MBC), which includes periodic administration of validated self-report measures assessing clinical symptoms, side effects, and treatment adherence,57 patient and treater review of data, and the use of that data at critical decision points to collaboratively re-evaluate the treatment plan and guide next-step interventions. MBC has been associated with more rapid time to remission in patients with TRD,58 although it can be challenging to implement in real-world practice.59

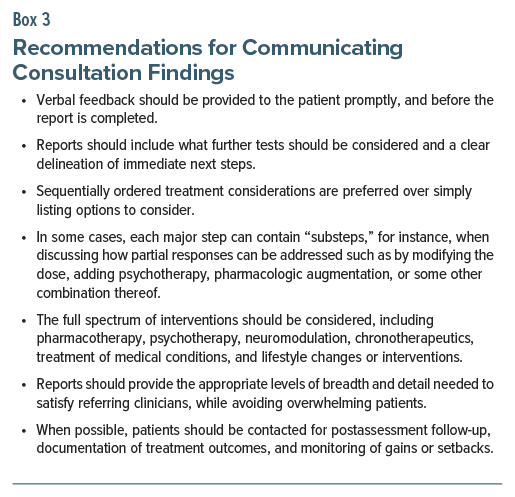

It is recommended that both the patient and the referring provider receive copies of the consultation report. Some practices may prefer providing patients with briefer “patient summary” reports. However, in our experience, most patients prefer to read the same document that their regular mental healthcare providers will also be viewing. Moreover, Federal rules (passed under the 21st Century Cures Act) that went into effect in 2022 require that patients have free access to their health records in digital format which, presumably, includes the complete TRD consultation report.60 Given the varied factors mentioned above, the section of the report that contains the treatment recommendations may be lengthy. A great deal of skill and practice is needed to provide the appropriate levels of breadth and detail to satisfy referring clinicians and avoid overwhelming patients. Using a standardized TRD Consultation Report EMR template, along with built-in EMR tools, can facilitate efficient and complete documentation. Verbal feedback should be provided to the patient before the final report is ready. In some cases, verbal feedback to patients (and perhaps to referring providers by telephone) can occur on the same day as the consultative visit. Alternatively, verbal feedback can be provided at a second “wrap up” visit, particularly if more information or testing is needed before final recommendations are made. For a summary of recommendations, see Box 3.

POSTASSESSMENT CONTACT

The postassessment phase refers to subsequent contact with patients or their referring providers after the consultation is completed. Often, postassessment contact is requested either because there are additional questions about the initial consultation that could not be addressed earlier or because there is a need for additional treatment guidance due to lack of success with the original set of recommendations. Postassessment visits can be scheduled in advance by the consultative service (eg, after 6 months or a year) or on an as-needed basis at the request of patients or their referring providers. Postassessment contact may be used to assess the patient’s response to the recommendations that were provided and to assess quality measures for the consultation service, including whether the recommendations were received or implemented. In some cases, the referring healthcare providers may not be comfortable with initiating some or all of the recommendations provided. Therefore, many TRD consultative practices offer a limited period of follow-up to manage patients through the initial stages of postconsultation treatment and provide information for specialist referral in the patients’ community to optimize continuity of care.

SUMMARY AND FUTURE DIRECTIONS

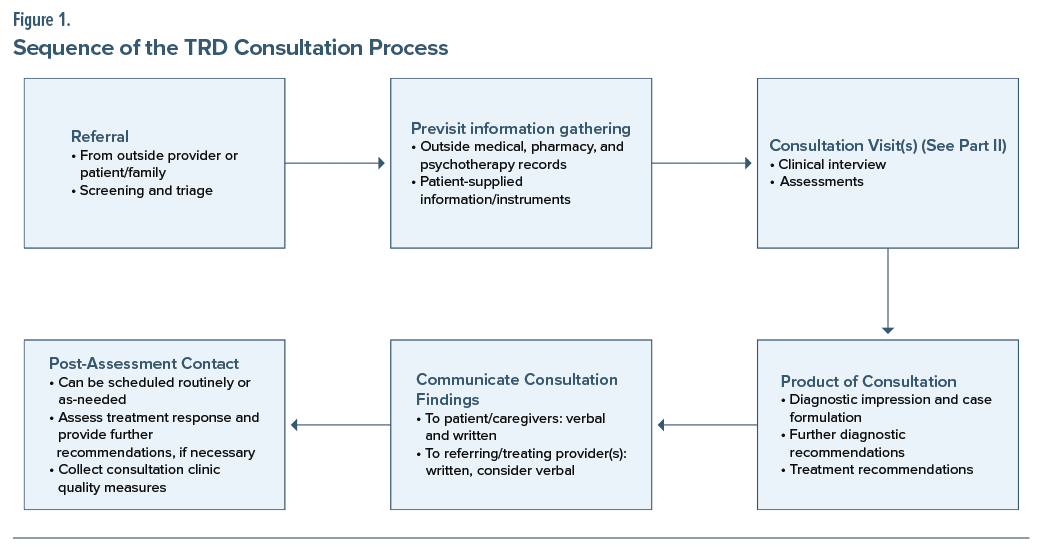

As rates of depression are growing in the US, in the coming years, centers of excellence and collaborative networks of such centers will play an increasingly important role in improving patient outcomes.17 TRD consultation programs within mental healthcare settings can provide access to experts who have advanced training and experience in mood disorder interventions. Consultations within these programs are meant to offer the patient and referring provider a roadmap for evidence-based interventions, to increase the likelihood of treatment response and sustained symptom remission. With the increasing development of TRD consultation programs nationally, important considerations for starting such a program and specific recommendations will likely evolve quickly. Our recommendations, reviewed here, represent an up-to-date consensus of the TRD Task Group of the NNDC and provide a starting point for continued dialogue. In this paper, we provided recommendations for the entire sequence of the consultation process, from receiving an initial referral to postconsultation contact (see Figure 1).

In the future, research reviewing existing TRD consultation programs will provide the basis for a general protocol for new program proposals. Future research reviewing provider and patient perceptions of barriers (ie, what has worked and what is not working so well) will help to inform equity-related recommendations for TRD consultation clinics. In addition, ongoing and future research examining patient-related outcomes, prognostic indicators, and the benefits of novel indications is strongly encouraged and will continue to inform the evolving recommendations.

Article Information

Published Online: April 28, 2025. https://doi.org/10.4088/JCP.24cs15335

© 2025 Physicians Postgraduate Press, Inc.

Submitted: March 8, 2024; accepted January 28, 2025.

To Cite: Voytenko VL, Conroy SK, Docherty AR, et al. Developing a treatment-resistant depression consultation program, part I: practical and logistical considerations. J Clin Psychiatry 2025;86(2):24cs15335.

Author Affiliations: Department of Psychiatry and Department of Medical Ethics, Humanities, and Law, Western Michigan University Homer Stryker M.D. School of Medicine, Kalamazoo, Michigan (Voytenko); Division of Psychiatry and Behavioral Medicine, Michigan State University College of Human Medicine, East Lansing, Michigan (Voytenko); Department of Psychiatry, Indiana University School of Medicine, Indianapolis, Indiana (Conroy); Department of Psychiatry, University of Utah School of Medicine and the Huntsman Mental Health Institute, Salt Lake City, Utah (Docherty); National Network of Depression Centers, Ann Arbor, Michigan (Burnett, Flood); Center for Interventional Psychiatry, Faillace Department of Psychiatry and Behavioral Sciences, McGovern Medical School, The University of Texas Health Science Center at Houston, Houston, Texas (Quevedo); Department of Psychiatry and Behavioral Sciences, Emory University School of Medicine, Atlanta, Georgia (Riva Posse); Depression Recovery Center, Department of Psychiatry and Behavioral Health, The Ohio State University Wexner Medical Center and College of Medicine, Columbus, Ohio (Virk, Fournier); Department of Psychiatry and Behavioral Sciences, University of Louisville School of Medicine, Louisville, Kentucky (Wright); Department of Behavioral Sciences and Social Medicine, Florida State University College of Medicine, Tallahassee, Florida (Bobo); Department of Psychiatry and Depression Center, University of Michigan, Ann Arbor, Michigan (Parikh).

Corresponding Author: Vitaliy L. Voytenko, PsyD, Department of Psychiatry, Western Michigan University Homer Stryker M.D. School of Medicine, 1000 Oakland Dr, Kalamazoo, MI 49008 ([email protected]).

Voytenko and Conroy contributed equally as first authors.

Fournier and Parikh contributed equally as senior authors.

Relevant Financial Relationships: Dr Conroy received research funding from Janssen. Dr Quevedo received clinical research support from LivaNova, has speaker bureau membership with Myriad Neuroscience and AbbVie, is a consultant for Eurofarma, is a stockholder at Instituto de Neurociencias, and receives copyrights from Artmed Editora, Artmed Panamericana, and Elsevier/ Academic Press. Dr Riva Posse has served as a consultant to LivaNova, Abbott, Janssen, and MotifNeuro and receives editorial fees from Elsevier. Dr Virk has received research funding from Johnson & Johnson (Janssen), Otsuka, Boeringer, Compass, Neumora, Allergan, DeNovo, Neurocrine, Novartis, and Relmada. Dr Wright has equity interest and serves as a consultant to Mindstreet, Inc., serves as consultant to Otsuka Pharmaceutical, and receives royalties from American Psychiatric Publishing, Inc. and Guilford Press. Dr Bobo’s research has been supported by the National Institutes of Health, Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality, National Science Foundation, Watzinger Foundation, Myocarditis Foundation, Blue Gator Foundation, and Mayo Foundation for Medical Education & Research, and he has contributed chapters to UpToDate regarding the pharmacological management of bipolar major depression. Dr Fournier receives royalties from Guilford Press. Dr Parikh reports research funding in the past 2 years from Aifred, Janssen, Compass, Sage, and Merck; consulting income from Mensante, Sage, Aifred, Boehringer-Ingelheim, Otsuka, and Janssen; and share ownership in Mensante. The other authors report no financial conflicts of interest.

Funding/Support: This work was supported by a Momentum Grant from the National Network of Depression Centers (NNDC), Ann Arbor, Michigan.

Role of the Sponsor: NNDC has had no influence on the conduct and publication of the project.

ORCID: Vitaliy L. Voytenko: https://orcid.org/0000-0002-0078-6256

Clinical Points

- The need for specialized treatment-resistant depression (TRD) consultation programs has been growing, but guidance on initiating and sustaining such programs has not been readily available.

- For patients with depressive disorders who do not respond to multiple adequate trials of standard treatments, a referral for subspecialty TRD consultation may provide a clarified diagnosis and a potentially more effective treatment strategy.

References (60)

- World Health Organization. Depression. World Health Organization; 2021. Accessed March 17, 2023. https://www.who.int/en/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/depression

- Ettman CK, Abdalla SM, Cohen GH, et al. Prevalence of depression symptoms in US adults before and during the COVID-19 pandemic. JAMA Netw Open. 2020;3(9):e2019686. CrossRef

- Bueno-Notivol J, Gracia-García P, Olaya B, et al. Prevalence of depression during the COVID-19 outbreak: a meta-analysis of community-based studies. Int J Clin Health Psychol. 2021;21(1):100196.

- Trevino K, McClintock SM, McDonald Fischer N, et al. Defining treatment-resistant depression: a comprehensive review of the literature. Ann Clin Psychiatry. 2014;26(3):222–232.

- Zimmerman M, McGlinchey JB, Posternak MA, et al. How should remission from depression be defined? The depressed patient’s perspective. Am J Psychiatry. 2006;163(1):148–150. CrossRef

- Nemeroff CB. Prevalence and management of treatment-resistant depression. J Clin Psychiatry. 2007;68(suppl 8):17–25.

- Ghaemi SN, Rosenquist KJ, Ko JY, et al. Antidepressant treatment in bipolar versus unipolar depression. Am J Psychiatry. 2004;161(1):163–165. CrossRef

- Rush AJ, Trivedi MH, Wisniewski SR, et al. Acute and longer-term outcomes in depressed outpatients requiring one or several treatment steps: a STAR*D report. Am J Psychiatry. 2006;163(11):1905–1917. CrossRef

- Rush AJ, Aaronson ST, Demyttenaere K. Difficult-to-treat depression: a clinical and research roadmap for when remission is elusive. Aust N Z J Psychiatry. 2019;53(2):109–118. CrossRef

- Zhdanava M, Pilon D, Ghelerter I, et al. The prevalence and national burden of treatment-resistant depression and major depressive disorder in the United States. J Clin Psychiatry. 2021;82(2):20m13699.

- Yager J, Langsley DG. The evolving subspecialization of psychiatry: implications for the profession. Am J Psychiatry. 1987;144(11):1461–1465.

- Shore JH. Order and chaos: subspecialization and american psychiatry. Acad Psychiatry. 1993;17(1):12–20.

- Bhugra D, Tasman A, Pathare S, et al. The WPA-lancet psychiatry commission on the future of psychiatry. Lancet Psychiatry. 2017;4(10):775–818. CrossRef

- Li J, Burson RC, Clapp JT, et al. Centers of excellence: are there standards? Healthc (Amst). 2020;8(1):100388. CrossRef

- Mehrotra A, Dimick JB. Ensuring excellence in centers of excellence programs. Ann Surg. 2015;261(2):237–239. CrossRef

- Manyazewal T, Woldeamanuel Y, Oppenheim C, et al. Conceptualising centres of excellence: a scoping review of global evidence. BMJ Open. 2022;12(2):e050419. CrossRef

- Elrod JK, Fortenberry JL Jr. Centers of excellence in healthcare institutions: what they are and how to assemble them. BMC Health Serv Res. 2017;17(suppl 1):425. CrossRef

- Pronovost PJ, Ata GJ, Carson B, et al. What is a center of excellence? Popul Health Manag. 2022;25(4):561–567. CrossRef

- Vieta E. Bipolar units and programmes: are they really needed? World Psychiatry. 2011;10(2):152. CrossRef

- Greden JF. The National Network of Depression Centers: progress through partnership. Depress Anxiety. 2011;28(8):615–621. CrossRef

- Fournier JC, Voytenko VL, Docherty AR, et al. Developing a treatment-resistant depression consultation program, part 2: assessment. J Clin Psychiatry. 2025;86(2):24cs15336.

- Parikh SV, Lopez D, Vande Voort JL, et al. Developing an IV ketamine clinic for treatment-resistant depression: a primer. Psychopharmacol Bull. 2021;51(3):109–124.

- Bishop TF, Press MJ, Keyhani S, et al. Acceptance of insurance by psychiatrists and the implications for access to mental health care. JAMA Psychiatry. 2014;71(2):176–181. CrossRef

- Byrow Y, Pajak R, Specker P, et al. Perceptions of mental health and perceived barriers to mental health help-seeking amongst refugees: a systematic review. Clin Psychol Rev. 2020;75:101812. CrossRef

- Cyr ME, Etchin AG, Guthrie BJ, et al. Access to specialty healthcare in urban versus rural US populations: a systematic literature review. BMC Health Serv Res. 2019;19(1):974. CrossRef

- Mongelli F, Georgakopoulos P, Pato MT. Challenges and opportunities to meet the mental health needs of underserved and disenfranchised populations in the United States. Focus. 2020;18(1):16–24. CrossRef

- Moroz N, Moroz I, D’Angelo MS. Mental health services in Canada: barriers and cost effective solutions to increase access. Healthc Manage Forum. 2020;33(6):282–287. CrossRef

- National Center for Health Workforce Analysis. Behavioral Health Workforce. Health Workforce Analysis; 2023. Accessed May 5, 2024. https://bhw.hrsa.gov/sites/default/files/bureau-health-workforce/Behavioral-Health-Workforce-Brief-2023.pdf

- Duffy FF, West JC, Wilk J, et al. Mental health practitioners and trainees. In Manderscheid RW, Berry JT, eds. Mental Health, United States, 2004. DHHS Pub No. (SMA)-06-4195. Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration; 2006:256–309.

- Keuroghlian AS, Marcus PH, Neufeld J, et al. Telehealth for psychiatry and mental healthcare can improve access and patient outcomes. Nat Med. 2023;29(11):2698–2700. CrossRef

- Ettman CK, Brantner CL, Albert M, et al. Trends in telepsychiatry and in-person psychiatric care for depression in an academic health system, 2017-2022. Psychiatr Serv. 2024;75(2):178–181. CrossRef

- Gamoran J, Xu Y, Buinewicz SAP, et al. An examination of depression severity and treatment adherence among racially and ethnically minoritized, low-income individuals during the COVID-19 transition to telehealth. Psychiatry Res. 2024;342:116221. CrossRef

- Shaker AA, Austin SF, Storebø OJ, et al. Psychiatric treatment conducted via telemedicine versus in-person modality in posttraumatic stress disorder, mood disorders, and anxiety disorders: systematic review and meta-analysis. JMIR Ment Health. 2023;10:e44790.

- van der Merwe M, Atkins T, Scott AM, et al. Diagnostic assessment via live telehealth (phone or video) versus face-to-face for the diagnoses of psychiatric conditions: a systematic review. J Clin Psychiatry. 2024;85(4):24r15296.

- Salerno SM, Hurst FP, Halvorson S, et al. Principles of effective consultation: an update for the 21st-century consultant. Arch Intern Med. 2007;167(3):271–275.

- Balestri M, Calati R, Souery D, et al. Socio-demographic and clinical predictors of treatment resistant depression: a prospective European multicenter study. J Affect Disord. 2016;189:224–232. CrossRef

- Bennabi D, Aouizerate B, El-Hage W, et al. Risk factors for treatment resistance in unipolar depression: a systematic review. J Affect Disord. 2015;171:137–141. CrossRef

- Fernando I, Cohen M, Henskens F. A systematic approach to clinical reasoning in psychiatry. Australas Psychiatry. 2013;21(3):224–230. CrossRef

- Haddad PM, Talbot PS, Anderson IM, et al. Managing inadequate antidepressant response in depressive illness. Br Med Bull. 2015;115(1):183–201. CrossRef

- Parker GB, Malhi GS, Crawford JG, et al. Identifying “paradigm failures” contributing to treatment-resistant depression. J Affect Disord. 2005;87(2–3):185–191. CrossRef

- Souery D, Oswald P, Massat I, et al. Clinical factors associated with treatment resistance in major depressive disorder: results from a European multicenter study. J Clin Psychiatry. 2007;68(7):1062–1070.

- Lam RW, Filteau MJ, Milev R. Clinical effectiveness: the importance of psychosocial functioning outcomes. J Affect Disord. 2011;132(suppl 1):S9–S13. CrossRef

- Langlieb AM, Guico-Pabia CJ. Beyond symptomatic improvement:assessing real-world outcomes in patients with major depressive disorder. Prim Care Companion J Clin Psychiatry. 2010;12(2):PCC.09r00826.

- Haynes SN, Williams AE. Case formulation and design of behavioral treatment programs. Eur J Psychol Assess. 2003;19(3):164–174. CrossRef

- Macneil CA, Hasty MK, Conus P, et al. Is diagnosis enough to guide interventions in mental health? Using case formulation in clinical practice. BMC Med. 2012;10:111. CrossRef

- Bergner RM. Characteristics of optimal clinical CFs. The linchpin concept. Am J Psychother. 1998;52(3):287–300.

- Westermeyer JJ, Weiss RD, Ziedonis DM. Integrated Treatment for Mood and Substance Use Disorders. JHU Press; 2003.

- Keitner GI, Mansfield AK. Management of treatment-resistant depression. Psychiatr Clin North Am. 2012;35(1):249–265. CrossRef

- Kornstein SG, Schneider RK. Clinical features of treatment-resistant depression. J Clin Psychiatry. 2001;62(suppl 16):18–25.

- Shelton RC, Osuntokun O, Heinloth AN, et al. Therapeutic options for treatment-resistant depression. CNS Drugs. 2010;24(2):131–161. CrossRef

- Dallaspezia S, Benedetti F. Chronobiological therapy for mood disorders. Expert Rev Neurother. 2011;11(7):961–970. CrossRef

- Ionescu DF, Rosenbaum JF, Alpert JE. Pharmacological approaches to the challenge of treatment-resistant depression. Dialogues Clin Neurosci. 2015;17(2):111–126. CrossRef

- Lipsman N, Sankar T, Downar J, et al. Neuromodulation for treatment-refractory major depressive disorder. CMAJ. 2014;186(1):33–39. CrossRef

- Papakostas GI. Managing partial response or nonresponse: switching, augmentation, and combination strategies for major depressive disorder. J Clin Psychiatry. 2009;70(suppl 6):16–25.

- Sarris J, O’Neil A, Coulson CE, et al. Lifestyle medicine for depression. BMC Psychiatry. 2014;14:107. CrossRef

- van Bronswijk S, Moopen N, Beijers L, et al. Effectiveness of psychotherapy for treatment-resistant depression: a meta-analysis and meta-regression. Psychol Med. 2019;49(3):366–379. CrossRef

- Hong RH, Murphy JK, Michalak EE, et al. Implementing measurement-based care for depression: practical solutions for psychiatrists and primary care physicians. Neuropsychiatr Dis Treat. 2021;17:79–90. CrossRef

- Mayes TL, Deane AE, Aramburu H, et al. Improving identification and treatment outcomes of treatment-resistant depression through measurement-based care. Psychiatr Clin North Am. 2023;46(2):227–245. CrossRef

- Lewis CC, Boyd M, Puspitasari A, et al. Implementing measurement-based care in behavioral health: a review. JAMA Psychiatry. 2019;76(3):324–335.

- Rodriguez JA, Clark CR, Bates DW. Digital health equity as a necessity in the 21st century cures act era. JAMA. 2020;323(23):2381–2382. CrossRef

This PDF is free for all visitors!