Abstract

Untreated depression may adversely affect pregnancy and offspring outcomes through several mechanisms; on the flip side, antidepressants used to treat depression may cross the placenta and affect the developing fetus and its brain. This article examines the research literature on gestational exposure to antidepressants and the risk of neurodevelopmental disorders (NDDs) in offspring. Two recent meta-analyses and 3 subsequently published observational studies, including 1 Asian study, are reviewed with especial focus on autism spectrum disorder (ASD) and attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD). Despite limitations of the literature, some conclusions can reasonably be drawn. In unadjusted analyses, which assist an understanding of real world risks, gestational exposure to antidepressant drugs is associated with an up to doubled risk of ASD and ADHD. However, in adjusted analyses, which assist an understanding of cause-effect relationships but not real world risks, the risks substantially attenuate and may lose statistical significance. The risks also lose statistical significance in analyses that address confounding by indication by comparing antidepressant-exposed and -unexposed pregnancies in women with psychiatric disorders. The likelihood of confounding by parental genes, parental environment, and parental health-related variables is suggested by findings that antidepressants remain significantly associated with NDDs when the exposure period is outside the pregnancy window (such as before or after but not during pregnancy) or when fathers are exposed to antidepressants during pregnancy. Finally, discordant sibling pair analyses suggest that whether or not a child develops an NDD is related to whether or not its sib has an NDD rather than whether or not the child was exposed to an antidepressant in utero. Discussion points are suggested for the shared decision-making process when counseling women about NDD risks associated with gestational exposure to antidepressant drugs. Take-home messages are summarized.

J Clin Psychiatry 2026;87(1):25f16226

Author affiliations are listed at the end of this article.

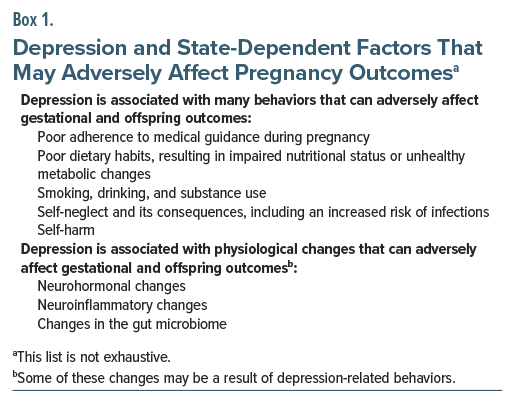

The safety of gestational exposure to psychotropic medication is a matter of importance. On the one hand, effective treatment of maternal major mental illness during pregnancy not only alleviates suffering but also attenuates the risk of harm to the pregnancy arising from illness-related risks (Box 1). On the other hand, most psychotropic medications cross the placenta and, in theory, may affect fetal health, including fetal neurodevelopment. Conducting randomized controlled trials (RCTs) during pregnancy could resolve uncertainty, but RCTs in pregnancy are ethically and logistically challenging. When RCTs are unavailable, inferences must necessarily be sought from observational studies.

This article examines studies on gestational exposure to antidepressant medication and the risk of neurodevelopmental disorders (NDDs) in offspring. Five studies are selected for review with especial focus on the most studied outcomes, autism spectrum disorder (ASD) and attention-deficit/ hyperactivity disorder (ADHD). The studies reviewed include 2 recent meta-analyses, 2 observational studies that appeared after the publication of the meta-analyses, and 1 very recent observational study that is the first to be conducted in an Asian sample. This article updates earlier articles in this column.1,2

Prelude

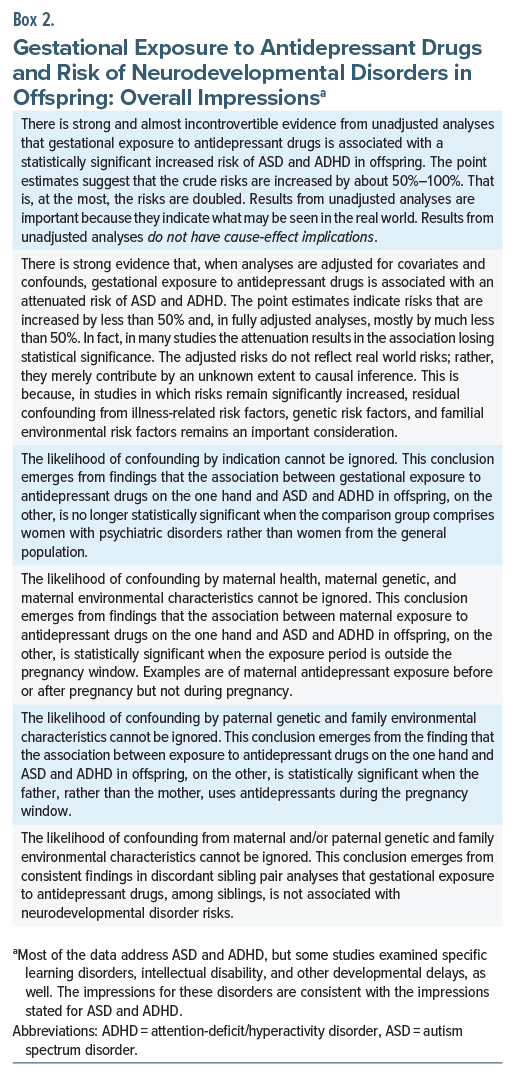

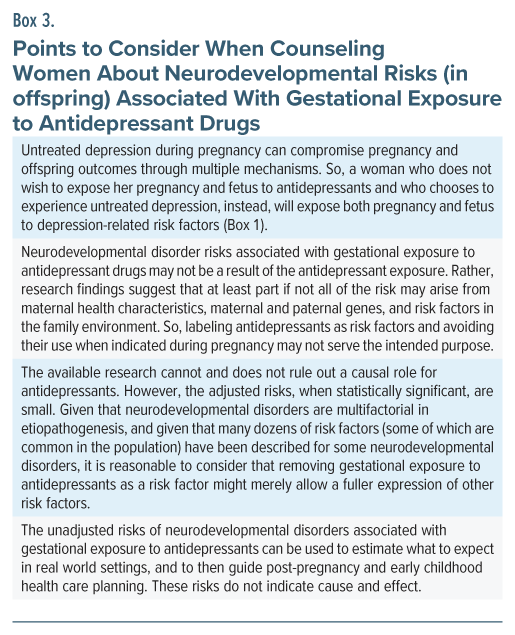

In order to provide the reader with a general summary of the literature review and the accompanying discussions, take-home messages and counseling points are provided in Boxes 2 and 3, respectively. Readers might find it useful to peruse the contents of these boxes now, and again after reading this article.

Meta-Analysis: Antidepressants and ASD3

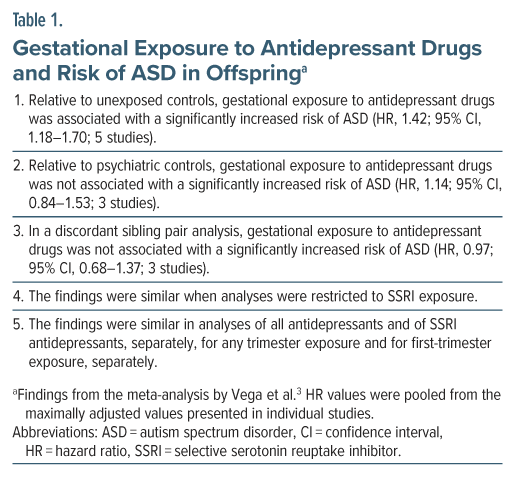

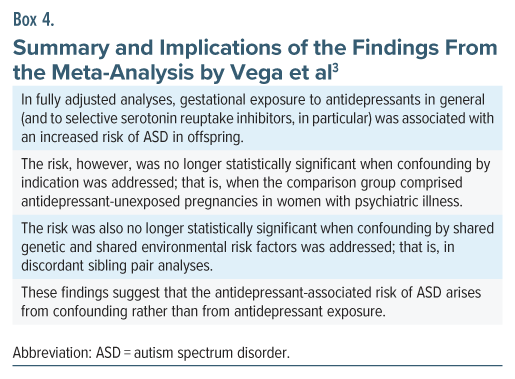

Vega et al3 described a systematic review and meta-analysis of the risk of ASD in offspring following gestational exposure to antidepressant drugs. Their study is important because they conducted additional analyses to indirectly address confounding by indication and confounding by genetic and environmental risk factors.

Their search identified 8 cohort and 6 case-control studies. Important findings, extracted only from forest plots that did not combine data from cohort and case-control studies,4 are presented in Table 1. The findings and the implications thereof are summarized in Box 4.

Meta-Analysis: Antidepressants, ASD, and ADHD5

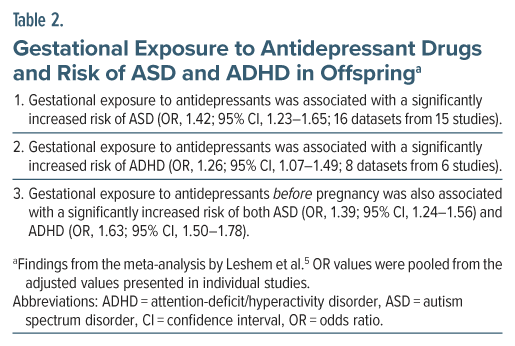

Leshem et al5 described a systematic review and meta-analysis of the risk of ASD and ADHD in offspring following gestational exposure to antidepressant drugs. Their study is important because it included 2 studies that Vega et al3 did not, because it also presented data on ADHD outcomes, and because it presented an analysis that indirectly addressed confounding by maternal risk factors.

There were 16 datasets from 15 studies in the ASD analysis and 8 datasets from 6 studies for the ADHD analysis. Important findings from the meta-analysis are presented in Table 2.

In summary, gestational exposure to antidepressant drugs was associated with a significantly increased risk of ASD as well as ADHD in offspring. However, pre-pregnancy exposure to antidepressants was also associated with an increased risk of both disorders. Because pre-pregnancy exposure does not result in in utero exposure, the finding implies that maternal characteristics (genes, environment, and psychiatric illness) rather than antidepressant exposure were responsible for the NDD risk.

There are 2 potentially serious limitations of this meta-analysis.5 One is that the authors pooled odds ratios (ORs) extracted from case-control studies with ORs extracted or computed from cohort studies; this is generally discouraged because ORs obtained from different study designs are conceptually different and possibly numerically different, as well.4 The other is that the authors did not explain how or even whether they addressed overlapping control groups in forest plots that contained more than 1 dataset from the same study; this is problematic because of double counting of control subjects in the forest plots. The findings of this meta-analysis should therefore be interpreted with caution.

Case-Control Study: Selective Serotonin Reuptake Inhibitors and NDDs6

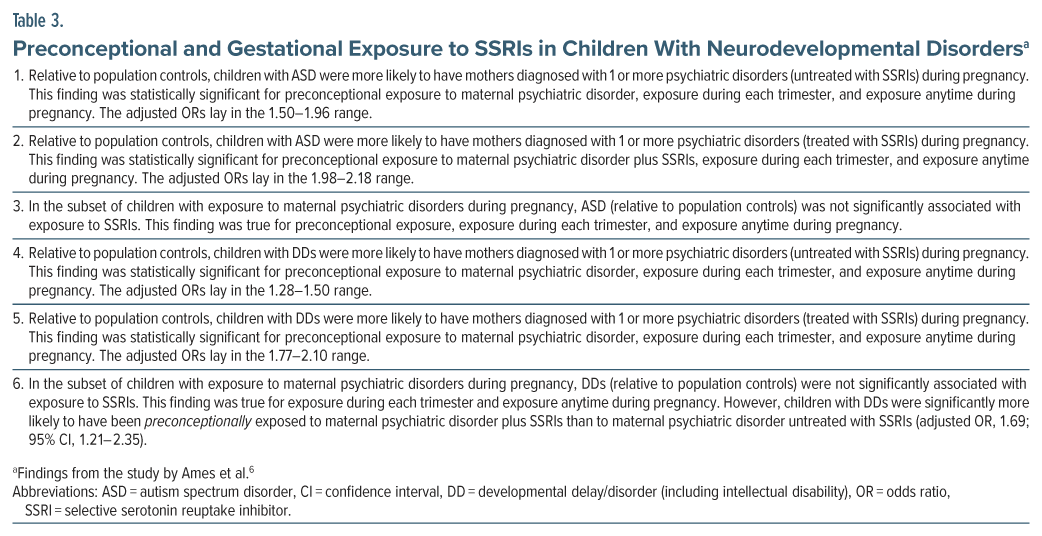

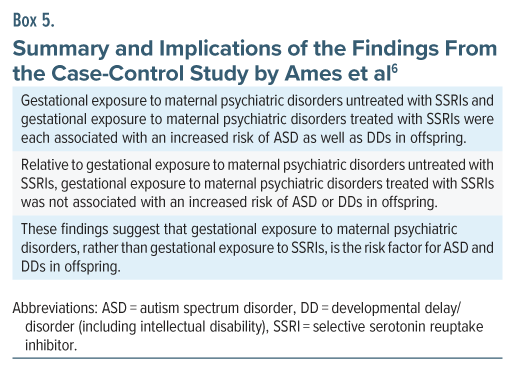

Ames et al6 described a case-control study of the association between ASD and developmental delays/disorders (DDs; intellectual disability included) on the one hand and gestational exposure to selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs), on the other. The data were drawn from the prospective Study to Explore Early Development, a multicenter study conducted in the US among children born during 2003–2011.

The sample comprised 1,367 children with ASD, 1750 children with DDs, and 1,671 randomly selected general population controls. Preconceptional (3 months before conception; not further defined) and gestational exposure to SSRIs (based on interviews with the mother) were compared between cases and controls in analyses that adjusted for maternal age, race, education, and smoking, and family income.

Important findings from the study are presented in Table 3 and are summarized in Box 5. Of note, in the population control analyses, the study found that, besides gestational exposure, preconceptional exposure to SSRIs was also associated with an increased risk of both ASD and DDs. This seems to suggest that maternal risk factors (genes, environment, health) rather than gestational exposure to SSRIs were responsible for the significant association between prenatal SSRI exposure on the one hand and ASD and DDs, on the other. However, such a conclusion is best not drawn from the study because the authors did not indicate that the analyses of preconceptional and gestational exposure were conducted on non-overlapping samples. The sample sizes presented for these analyses suggested that, in fact, there was likely to have been overlap.

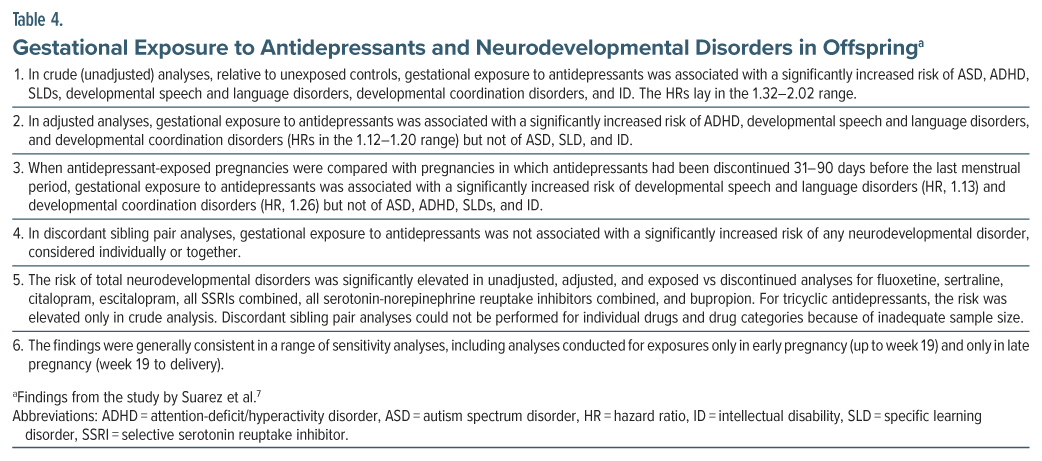

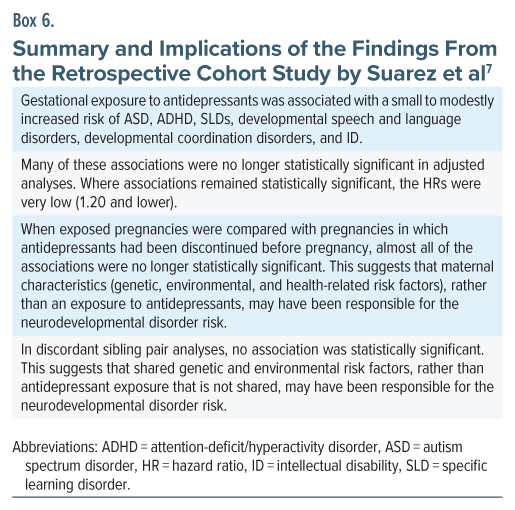

Cohort Study: Antidepressants and NDDs7

Suarez et al7 described a retrospective cohort study of the association between gestational exposure to antidepressant drugs and NDDs in offspring. There were 2 cohorts, drawn from public and private insurance sectors in the US for the years 2000–2015. The pooled sample included 145,702 antidepressant-exposed and 3,032,745 unexposed pregnancies with exposure defined as at least 1 prescription for an antidepressant dispensed between week 19 of gestation and the date of delivery. This exposure window was selected to represent the period of synaptogenesis. Unexposed pregnancies were those in which no antidepressant was dispensed from 90 days before the last menstrual period to the end of pregnancy.

Analyses were conducted for each cohort separately and were adjusted for a wide range of maternal demographic, lifestyle, health, and other covariates and confounds. The findings from the 2 cohorts were pooled using fixed effect meta-analysis. Important findings from the study are presented in Table 4 and summarized in Box 6.

A disconcerting aspect of this study is that the prevalences of NDDs were so high as to cast serious doubt on what exactly was being diagnosed. In the two databases, the cumulative incidence of total NDDs, at age 12 years, was 47% vs 25% in antidepressant-exposed and unexposed offspring in one cohort, and 31% vs 15%, respectively, in the other cohort. The values were a staggering 33% vs 20% and 18% vs 10% for ADHD, but more credible at 4.1% vs 2.1% and 2.9% vs 1.6% for ASD. If diagnostic errors are comparable in exposed and unexposed groups, they may cancel out in statistics such as the hazard ratio. However, such an assumption is fraught with uncertainty, and so the findings of this study must therefore be cautiously interpreted.

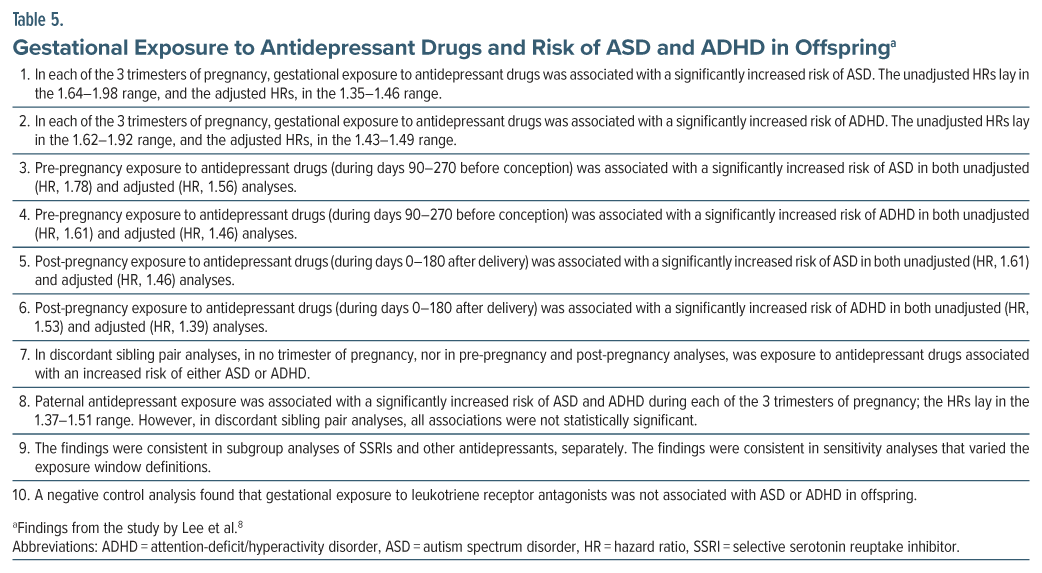

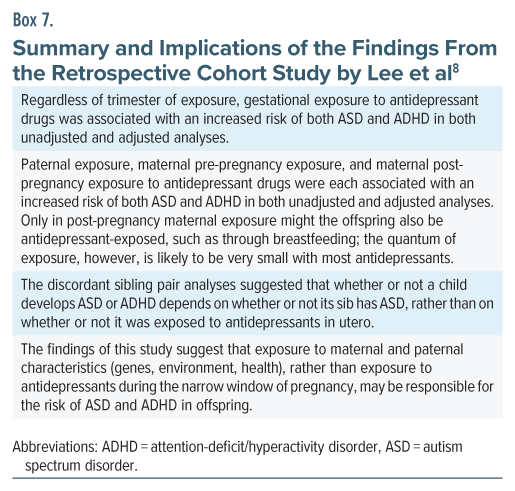

Cohort Study: Antidepressants, ASD, and ADHD8

Lee et al8 described the first Asian study in the field. Using linked registers in Taiwan, they identified all liveborn children (n = 2,301,396) during 2014–2016 and examined neurodevelopmental outcomes across an unstated duration of follow-up.

Gestational exposure to antidepressants, based on drug dispensation, was classified into prepregnancy exposure (90–270 days before conception), first-trimester exposure (0–90 days before conception plus days 0–90 of pregnancy), second-trimester exposure (days 91–180 plus days 0–90), third-trimester exposure (days 181–270 plus days 91–180), and postpregnancy exposure (days 0–180 after delivery). The extra 90 days before each trimester were included in the trimester’s exposure window because prescriptions might have been issued for a 90-day supply, and because the supply would enter the trimester window even if dispensation occurred during the previous 90 days. As a result, there was considerable overlap in the samples in the analyses for each exposure classification.

Antidepressant-unexposed status was defined as no antidepressant dispensation from 270 days before pregnancy to 180 days after pregnancy. ASD and ADHD diagnoses were based on ICD-9 and ICD-10, and required a record of at least 1 inpatient or at least 3 outpatient diagnoses. Analyses were adjusted for a very limited range of covariates that included parental age and parental history of bipolar disorder and schizophrenia.

There were 55,707 exposed offspring and 2,245,689 unexposed offspring. ASD was recorded in 1.5% vs 1.0% of exposed vs unexposed offspring, and ADHD in 5.9% vs 4.0%. Important findings from the study are presented in Table 5 and are summarized in Box 7.

A point of interest in this study is that no association lost statistical significance in adjusted analyses; this is likely to be because of the very limited number of covariates included in the adjusted models. A point of concern is that the authors did not clarify whether the definition of pre-pregnancy and post-pregnancy exposure excluded gestational exposure; however, the discordant sibling pair analyses would continue to support the implications stated in Box 7. Another point of concern is that maternal exposure to antidepressants was not included as a covariate in the paternal exposure analyses. The reassuring findings of this study should therefore be viewed with caution.

General Reflections

There are no perfect studies or meta-analyses in the field. Yet, if one tries to make sense of what one reads, conclusions may be drawn, though with varying degrees of certainty. These conclusions were summarized in Box 2.

Concluding Notes

This review is not exhaustive. Other studies have also reported that gestational exposure to antidepressants is not associated with an increased risk of NDDs in offspring.9–11

Points to consider when counseling women were presented in Box 3. The final decision about whether or not to use an antidepressant to treat depression during pregnancy should, of course, be based on a shared and documented decision-making process.

Article Information

Published Online: December 17, 2025. https://doi.org/10.4088/JCP.25f16226

© 2025 Physicians Postgraduate Press, Inc.

To Cite: Andrade C. Gestational exposure to antidepressants and neurodevelopmental disorders in offspring. J Clin Psychiatry 2026;87(1):25f16226.

Author Affiliations: Department of Clinical Psychopharmacology and Neurotoxicology, National Institute of Mental Health and Neurosciences, Bangalore, India; Department of Psychiatry, Kasturba Medical College, Manipal Academy of Higher Education, Manipal, India.

Corresponding Author: Chittaranjan Andrade, MD, Department of Clinical Psychopharmacology and Neurotoxicology, National Institute of Mental Health and Neurosciences, Bangalore 560029, India ([email protected]).

Relevant Financial Relationships: None.

Funding/Support: None.

Each month in his online column, Dr Andrade considers theoretical and practical ideas in clinical psychopharmacology with a view to update the knowledge and skills of medical practitioners who treat patients with psychiatric conditions.

Each month in his online column, Dr Andrade considers theoretical and practical ideas in clinical psychopharmacology with a view to update the knowledge and skills of medical practitioners who treat patients with psychiatric conditions.

Department of Clinical Psychopharmacology and Neurotoxicology, National Institute of Mental Health and Neurosciences, Bangalore, India. Please contact Chittaranjan Andrade, MD, at Psychiatrist.com/contact/andrade.

References (11)

- Andrade C. Antidepressant exposure during pregnancy and risk of autism in the offspring, 1: Meta-review of meta-analyses. J Clin Psychiatry. 2017;78(8):e1047–e1051. PubMed CrossRef

- Andrade C. Antidepressant exposure during pregnancy and risk of autism in the offspring, 2: do the new studies add anything new? J Clin Psychiatry. 2017;78(8):e1052–e1056. PubMed CrossRef

- Vega ML, Newport GC, Bozhdaraj D, et al. Implementation of advanced methods for reproductive pharmacovigilance in autism: a meta-analysis of the effects of prenatal antidepressant exposure. Am J Psychiatry. 2020;177(6):506–517. PubMed CrossRef

- Andrade C. Towards a further understanding of meta-analysis using gestational exposure to cannabis and birth defects as a case in point. J Clin Psychiatry. 2024;85(4):24f15673. PubMed CrossRef

- Leshem R, Bar-Oz B, Diav-Citrin O, et al. Selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs) and serotonin norepinephrine reuptake inhibitors (SNRIs) during pregnancy and the risk for autism spectrum disorder (ASD) and attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) in the offspring: a true effect or a bias? A systematic review and meta-analysis. Curr Neuropharmacol. 2021;19(6):896–906. PubMed CrossRef

- Ames JL, Ladd-Acosta C, Fallin MD, et al. Maternal psychiatric conditions, treatment with selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors, and neurodevelopmental disorders. Biol Psychiatry. 2021;90(4):253–262. PubMed CrossRef

- Suarez EA, Bateman BT, Hernández-Díaz S, et al. Association of antidepressant use during pregnancy with risk of neurodevelopmental disorders in children. JAMA Intern Med. 2022;182(11):1149–1160. PubMed CrossRef

- Lee MJ, Chen YL, Wu SI, et al. Association between maternal antidepressant use during pregnancy and the risk of autism spectrum disorder and attention deficit hyperactivity disorder in offspring. Eur Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2024;33(12):4273–4283. PubMed CrossRef

- Lupattelli A, Mahic M, Handal M, et al. Attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder in children following prenatal exposure to antidepressants: results from the Norwegian mother, father and child cohort study. BJOG. 2021;128(12):1917–1927. PubMed CrossRef

- Hartwig CAM, Robiyanto R, de Vos S, et al. In utero antidepressant exposure not associated with ADHD in the offspring: a case control sibling design. Front Pharmacol. 2022;13:1000018. PubMed CrossRef

- Esen BÖ, Ehrenstein V, Nørgaard M, et al. Prenatal antidepressant exposure and the risk of attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder in childhood: accounting for misclassification of exposure. Epidemiology. 2023;34(4):476–486. PubMed CrossRef

This PDF is free for all visitors!