Abstract

Objective: This review of the relationship between idiopathic hypersomnia and psychiatric disorders describes considerations in recognizing and managing complaints of excessive daytime sleepiness (EDS) in patients in psychiatric clinical practice.

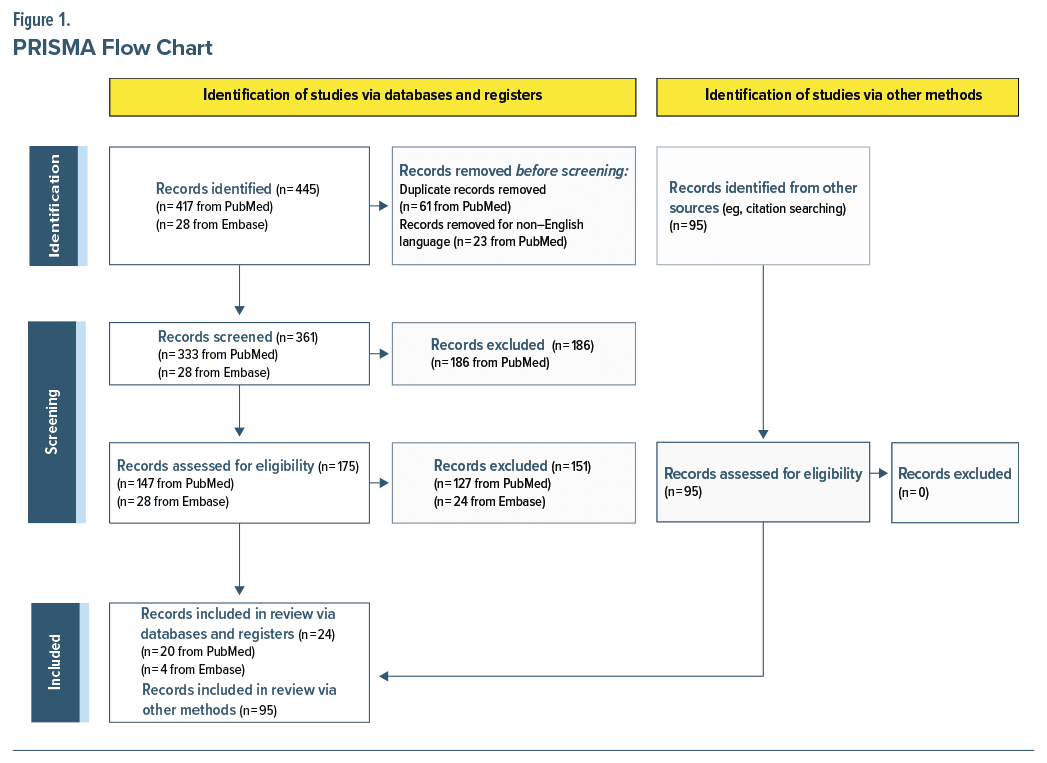

Data Sources: Terms including “idiopathic hypersomnia” and “psychiatric” were used to search PubMed and Embase for English-language publications of human studies from inception to July 2024.

Study Selection: Articles were manually screened for relevance to idiopathic hypersomnia pathophysiology, diagnosis, and treatment and EDS in psychiatric populations. Reference lists of identified articles were manually searched for additional relevant publications.

Data Extraction: Formal data charting was not performed.

Results: A total of 119 articles were included. Idiopathic hypersomnia is a central sleep disorder with the primary complaint of EDS, diagnosed prevalence of 0.037%, and estimated population prevalence up to 1.5%. Other prominent symptoms include sleep inertia, long sleep time, autonomic nervous system dysfunction, brain fog, and cognitive complaints. A high proportion of patients with idiopathic hypersomnia experience psychiatric comorbidities, including mood disorders and attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder. Assessing individuals with psychiatric disorders and complaints of hypersomnolence can pose diagnostic challenges. Diagnosis and treatment may be complicated by possible exacerbation of EDS by psychiatric medications and, conversely, exacerbation of psychiatric symptoms by idiopathic hypersomnia treatments.

Conclusions: Psychiatric clinicians are more likely to encounter patients with idiopathic hypersomnia than would be expected given its overall prevalence due to increased rate of psychiatric symptom comorbidity in this population. Recognizing and managing idiopathic hypersomnia for individuals with psychiatric conditions may lead to improvements in treatment outcome for patients.

J Clin Psychiatry 2025;86(3):24nr15718

Author affiliations are listed at the end of this article.

Idiopathic hypersomnia is a central disorder of hypersomnolence characterized by chronic, unexplained excessive daytime sleepiness (EDS) confirmed by objective sleep testing.1,2 Individuals with idiopathic hypersomnia experience substantial burdens, including impaired work productivity and daily activity and poor quality of life (QoL). In many cases, diagnosis is delayed considerably, due to the common and nonspecific symptom of sleepiness and lack of awareness of idiopathic hypersomnia.3,4 Timelier consideration of idiopathic hypersomnia and referral to a sleep specialist can lead to earlier diagnosis and treatment, which can reduce disease severity and improve QoL.2,5 Idiopathic hypersomnia often co-occurs with psychiatric symptoms. The prevalence of psychiatric comorbidities among individuals with idiopathic hypersomnia exceeded 50% in a clinical series, and an insurance claims–based analysis identified 3.7-fold increased odds of comorbid mental health diagnosis in individuals with an idiopathic hypersomnia claim compared with matched general-population controls.6,7 Greater awareness of idiopathic hypersomnia in psychiatric clinical practice could contribute to improving outcomes for patients with these conditions.

Idiopathic hypersomnia may be more prevalent in women, and onset typically occurs in adolescence or early adulthood.1,2 Its prevalence appears to be rising, although reported estimates vary owing to methodological differences between studies. The prevalence of probable idiopathic hypersomnia was 1.5% in a cohort of 792 adults who underwent objective sleep testing as part of the longitudinal Wisconsin Sleep Cohort (WSC) study.8 This finding is consistent with the 1.5% prevalence of hypersomnia disorder observed in an earlier population study of 15,929 adults, based on subjective symptoms obtained in interviews.9 In an administrative claims analysis, the estimated unweighted diagnosed prevalence of idiopathic hypersomnia increased from 32.1 (0.032%) to 37.0 (0.037%) per 100,000 persons from 2019–2021.10 In a retrospective cohort study that used medical encounter and prescription claims to estimate the prevalence of various sleep disorders, idiopathic hypersomnia prevalence increased by 32% from 2013–2016 (ie, 7.8–0.3 per 100,000 persons).11 A 2016 systematic review reported a general population prevalence of 0.002%–0.01%; prevalence among people referred for EDS evaluation was 10.3%–28.5%.12 Requirements of sleep laboratory testing for diagnosing idiopathic hypersomnia and the lack of board-certified sleep specialists may contribute to low diagnosis rates.8,13

According to the International Classification of Sleep Disorders criteria (Third Edition, Text Revision; ICSD-3-TR), idiopathic hypersomnia diagnosis requires objective sleep testing with overnight polysomnography (PSG) followed by a Multiple Sleep Latency Test (MSLT) to confirm EDS and rule out other sleep disorders such as narcolepsy and obstructive sleep apnea (OSA).1 Individuals with idiopathic hypersomnia may demonstrate long sleep duration (PSG-recorded total sleep time [TST] ≥660 minutes within a 24-hour period) not explained by another disorder and/or a high propensity for falling asleep (mean sleep latency [MSL] ≤8 minutes on MSLT).1 These symptoms are chronic (lasting ≥3 months), daily, and not the result of insufficient sleep, which can be ruled out by wrist actigraphy over ≥1 week. Beyond the core symptom of EDS, idiopathic hypersomnia is heterogeneous. Common features include high sleep efficiency, severe sleep inertia, long and unrefreshing naps, symptoms suggestive of autonomic nervous system dysfunction (eg, orthostatic disturbance and cold extremities), memory/attention deficits, and depression symptoms.1

Idiopathic hypersomnia differs from narcolepsy type 1 (NT1) by absence of cataplexy symptoms, and from both NT1 and narcolepsy type 2 (NT2) by involvement of < 1 sleep-onset rapid eye movement (REM) period (SOREMP) during combined PSG/MSLT. People with narcolepsy also more typically report symptoms of hypnagogic or hypnopompic hallucinations during wake–sleep or sleep–wake transitions (respectively), sleep paralysis, disrupted nighttime sleep (arousals, awakenings, fragmentation), and REM sleep behavior disorder. People with narcolepsy also typically do not have increased TST and describe naps as refreshing.1,14

An added challenge in recognizing idiopathic hypersomnia is that EDS is highly prevalent in the general population, particularly in people diagnosed with mood and anxiety disorders.15–19 The Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fifth Edition, Text Revision (DSM-5-TR) includes sleep disturbance involving hypersomnia as a possible diagnostic criterion for bipolar disorder involving major depressive episodes, major depressive disorder (MDD), and other depressive disorders.20 Ruling out other possible causes of EDS may also be challenging in psychiatric populations because of the high prevalence of OSA, a more common sleep disorder with high rates of psychiatric comorbidity.21 Additionally, the frequency of circadian rhythm disruption,22 and the widespread use of medications that can cause EDS (including antidepressants, antiseizure medications, antihistamines, antihypertensives, antipsychotics, hypnotics, and opioids) can also hamper diagnosis.12 Furthermore, sleepiness, defined as propensity to fall asleep, is often confused with fatigue, which is need for rest.23 Individuals who report excessive sleepiness may not show objective evidence of this symptom.

Among 290 surveyed individuals with idiopathic hypersomnia, 67% strongly (38%) or somewhat (29%) agreed “there were unreasonable delays in getting to my diagnosis.”4 Lack of sleep medicine education and limited access to sleep diagnostic services/providers are likely contributors to such delays. Among 305 surveyed physicians in the United States, 64% agreed there is insufficient understanding of idiopathic hypersomnia among physicians, and 92% agreed the negative impact of idiopathic hypersomnia is underestimated.24 Only 34% of participating psychiatrists reported being “extremely familiar” with idiopathic hypersomnia versus 60% of neurologists, 62% of pulmonologists, and 29% of primary care physicians.24 Because people with idiopathic hypersomnia experience psychiatric disorders at rates exceeding the general population,3,6,7 psychiatric clinicians may be more likely than other medical specialists to encounter patients with this condition in clinical practice and are well positioned to identify individuals benefitting from diagnostic sleep testing. This review describes the complex interrelationship between idiopathic hypersomnia and psychiatric disorders regarding comorbidity and pathophysiology, plus key considerations in recognizing and managing idiopathic hypersomnia in psychiatric clinical practice.

METHODS

In this literature review, PubMed was searched for English-language articles on human studies (no publication year constraints from inception to July 2024, when the search was conducted). Search terms included, but were not limited to, (“idiopathic hypersomnia” AND [“psychiatric” OR “depression” OR “anxiety” OR “ADHD” OR “schizophrenia” OR “bipolar” OR “mood disorder” OR “infection”]) and (“excessive daytime sleepiness” AND “psychiatric”). Reference lists of identified articles were manually searched for additional relevant publications (Figure 1). Embase was searched from inception to July 2024 for pertinent published conference abstracts using the following query: AB,TI(“idiopathic hypersomnia”) AND psychiatr* AND AB,TI(depression OR anxiety OR ADHD OR schizophrenia OR bipolar OR “mood disorder”). To supplement the search queries, additional targeted searches were conducted for relevant topics/ sections using variations and groupings of the terms listed previously and including the terms hypersomnia, cognitive, behavior, mood, sleepiness. A formal review protocol was not used.

PATHOPHYSIOLOGY OF IDIOPATHIC HYPERSOMNIA

The pathophysiology of idiopathic hypersomnia is not well understood; possible mechanisms include increased γ-aminobutyric acid (GABA)-ergic activity, altered noradrenergic and dopaminergic activity, circadian rhythm disruption, altered functional connectivity of the default mode network (DMN), and autonomic dysfunction. The link between idiopathic hypersomnia and increased GABA activity is supported by the finding that cerebrospinal fluid samples from a subset of people with idiopathic hypersomnia potentiated GABAA receptor activity in vitro.25 Symptoms of idiopathic hypersomnia are responsive to oxybate, which is thought to act primarily on GABAB receptors at dopaminergic, noradrenergic, and thalamocortical neurons and evokes a transient dopamine increase during washout.26–28

Individuals with idiopathic hypersomnia tend to have a late chronotype, consistent with delayed sleep phase syndrome (DSPS). Severe sleep inertia is also associated with idiopathic hypersomnia and DSPS.29–31 Samples of dermal fibroblasts from people with PSG/MSLT confirmed idiopathic hypersomnia demonstrated abnormal circadian gene expression.32 Functional neuroimaging findings suggest people with idiopathic hypersomnia have structural and functional connectivity abnormalities in the DMN, which has been implicated in sleep physiology.33–35

Autonomic dysfunction may share an underlying pathophysiology with idiopathic hypersomnia.36 Among 62 patients with objectively diagnosed idiopathic hypersomnia, 46% reported cold extremities, 32% feeling faint, 25% temperature dysregulation, and 23% palpitations; rates were significantly higher than those of a healthy control group (which reported rates of 20%, 9%, 2%, and 5%, respectively).37 Another cohort of 24 patients with PSG/MSLT-confirmed idiopathic hypersomnia had significantly higher Composite Autonomic Symptom Score–31 (COMPASS-31) scores (reflecting autonomic symptom severity) overall compared with the control group (n = 81). Orthostatic and vasomotor domain scores were also higher in the idiopathic hypersomnia cohort. The COMPASS-31 overall score was positively correlated with EDS severity and negatively correlated with QoL.36 An analysis of heart rate variability (HRV), a marker of autonomic dysfunction, demonstrated greater parasympathetic activity and elevated heart rate response to arousal in people with idiopathic hypersomnia with long sleep time (LST), suggesting increased vagal activity.38

That psychiatric disorders and idiopathic hypersomnia share pathophysiologic features suggests they may be mechanistically related. Altered neurotransmitter signaling is a hallmark of psychiatric disorders, and there is substantial overlap in the specific neurotransmitters implicated in psychiatric disorders and in idiopathic hypersomnia. For example, the GABAergic, norepinephrine, and dopamine systems have been implicated in MDD.39–41 Similarly, delayed sleep phase is associated with depression, bipolar disorder, and anxiety, and functional connectivity abnormalities involving the DMN have been described in MDD, bipolar disorder, schizophrenia, anxiety, and attention-deficit/ hyperactivity disorder (ADHD).42–44 Altered HRV has also been reported in people with psychiatric conditions, including depression, anxiety disorders, and schizophrenia; however, HRV measurement methods and control of possible confounders were highly variable across studies.45 A meta-analysis found predominantly decreased HRV associated with psychiatric disorders, while a study of HRV in people with idiopathic hypersomnia reported a more complex profile of increased high-frequency HRV and decreased low frequency/high-frequency HRV ratio.38,45,46 Twin studies indicate a genetic association between depressive symptoms, short or long sleep duration,47 and EDS.48

RELATIONSHIP BETWEEN IDIOPATHIC HYPERSOMNIA AND PSYCHIATRIC CONDITIONS

Studies of people with idiopathic hypersomnia have consistently demonstrated a high prevalence of psychiatric comorbidities, notably depression, anxiety, mood disorders, and ADHD.7,49–51 In a real-world administrative claims–based analysis of 11,412 people with medical claims for idiopathic hypersomnia and 57,058 matched controls, the idiopathic hypersomnia group experienced significantly higher odds of all comorbidities, including 3.7-fold increased odds of a mental health diagnosis (95% CI, 3.6–3.9), with 3.8-fold increased odds of mood disorders (95% CI, 3.7–4.0), 3.5- fold increased odds of depressive disorders (95% CI, 3.4–3.7), and 2.8-fold increased odds of anxiety disorders (95% CI, 2.7–2.9).7 A similar administrative claims analysis of people newly diagnosed with idiopathic hypersomnia (n = 4,980) found mood disorders, depressive disorders, and anxiety were among the most prevalent comorbidities overall, affecting 32.1%, 31.0%, and 30.7%, respectively, of patients in the idiopathic hypersomnia cohort compared with 7.8%, 7.0%, and 8.8% in the general-population cohort (n = 32,948,986).49 Among 75 adults with self-reported idiopathic hypersomnia who participated in an online survey, 44.0% reported having ≥1 psychiatric comorbidity (34.7% anxiety, 12.0% MDD, 8.0% bipolar or any psychotic disorder), 62.7% reported moderate to severe cognitive complaints, and 66.7% moderate to severe depressive symptoms.3

Although idiopathic hypersomnia was not necessarily diagnosed by objective sleep testing in the aforementioned studies, smaller studies in patients diagnosed by PSG/MSLT demonstrated similar trends. In a retrospective chart review of 145 patients with idiopathic hypersomnia and 53 patients with narcolepsy, 55.8% of those with idiopathic hypersomnia and 39.6% of those with narcolepsy had ≥1 psychiatric comorbidity.50 Mood disorders were most common, and ADHD and bipolar disorder were also increased in both groups.50 Among patients with central disorders of hypersomnolence diagnosed at a single sleep center, 53.8% (21/39) of participants with idiopathic hypersomnia reported psychiatric comorbidities compared with 38.1% (33/87) of participants with NT1 and 45.5% (10/22) of participants with NT2; in addition, Idiopathic Hypersomnia Severity Scale (IHSS) scores were positively correlated with Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale (HADS) anxiety and depression scores (P < .0001 and P = .0005, respectively).6 An observational study of 601 participants with central hypersomnia and MSLT-confirmed EDS included 68 participants with NT2 and 25 with idiopathic hypersomnia.52 Among participants evaluated using the Beck Depression Inventory, 20% with NT2 and 4% with idiopathic hypersomnia experienced moderate or severe depression.52 The presence of moderate or severe depression was associated with greater subjective EDS (higher scores on Epworth Sleepiness Scale [ESS]), worse sleep quality (higher Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index scores), and worse physical and mental health (lower 36- Item Short Form Health Survey scores).52 Conversely, in a series of 19 people with idiopathic hypersomnia who underwent psychiatric evaluation, 16 (84.2%) had no depressive symptoms, 2 had mild depressive symptoms, and 1 had atypical depression.53

ADHD symptomatology was identified in 21/ 40 patients with idiopathic hypersomnia in a cross sectional study.51 In an exploratory study of hyperactivity, 7 participants with NT2 and 5 with idiopathic hypersomnia reported more symptoms of inattention and hyperactivity on the Adult ADHD Self Report Scale than 12 controls, although actigraphic movement was similar between groups.54

No studies have evaluated idiopathic hypersomnia prevalence specifically in individuals with psychiatric disorders. People with psychiatric conditions have a high prevalence of hypersomnia based on subjectively reported EDS or sleep time; however, subjective EDS findings (ESS score ≥10) may be inconsistent with objective EDS (ie, MSLT <8 minutes).19 In a cross sectional case–control study, 40% of 81 individuals with bipolar disorder had ESS score >10 compared with 18% of 79 healthy controls.55 In a cohort of 2,259 adults ≥65 years old, ESS score >10 was associated with more severe depressive symptoms and lifetime history of manic/hypomanic episodes.56 In a retrospective analysis of 703 people with major depression, the prevalence of ESS score >10 was 50.8%, and individuals meeting this criterion had significantly shorter sleep latency, higher sleep efficiency, and higher apnea–hypopnea index but did not differ in TST or other PSG parameters.57 Adults with ADHD in a cross sectional study also reported high rates of EDS, with 47/100 participants having an ESS score >10, of whom 22 met DSM-5 criteria for hypersomnolence disorder.51

Several general-population studies support an association between depression and hypersomnolence or EDS.15–17 Of 2,167 adults in a population study, 33% had EDS (ESS score >10), and depression was an independent predictor of EDS.15,16 In a general-population sample of 1741 adults completing a survey and overnight PSG, moderate to severe EDS incidence was 8.2%, and EDS was significantly associated with depression and objective indicators of sleep fragmentation and sleep propensity.17 Remitted and severe MDD (but not mild to moderate depression) were associated with EDS risk in 105 adolescents recruited through a hospital sleep laboratory’s database, 34.3% of whom had an ESS score >10.58 In a clustering analysis of 75 people with hypersomnolence without an explanatory diagnosis (PSG/MSLT results inconsistent with narcolepsy, OSA, insufficient sleep syndrome, periodic limb movement disorder, or circadian rhythm disorder), depressive symptomatology clustered with more severe subjective sleep–wake symptoms, longer TST, and shorter wakefulness after sleep onset on PSG.59

Possible delays in diagnosis make assessing causality between sleep disorders and psychiatric disorders difficult. A longitudinal study of 1,200 young adults found those reporting hypersomnia in diagnostic interviews at study entry had increased odds of new-onset MDD, anxiety, and alcohol or drug abuse/dependence over a 3.5-year follow up period.60 A meta-analysis of sleep disturbances and first-onset major mental disorders, involving 25 datasets and >42,000 participants, found individuals with a history of sleep disturbance—self-reported, observer rated, or PSG-recorded insomnia, combination of insomnia and daytime fatigue, hypersomnia, or diagnosis of a sleep disorder—had increased odds of developing a mood or psychotic disorder.61 Self-reported or observer-rated hypersomnia was associated with onset of a major mental health disorder.61 In contrary, a retrospective analysis of 220 adults found subjective sleepiness was weakly positively correlated with HADS anxiety and depression scores, but there was no significant correlation between HADS scores and either MSL or an objective diagnosis of hypersomnia disorder (narcolepsy or idiopathic hypersomnia).62

Other studies also report discrepancies between subjective and objective sleepiness as they relate to depression, suggesting depression may leave people feeling sleepy without increasing sleep propensity.63,64 Among 1,287 adults in the WSC study, subjective sleepiness and self-reported LST (≥9 hours) were associated with increased odds of depression; paradoxically, MSL <8 minutes on MSLT was associated with decreased odds of depression.63 Additionally, in a WSC-based longitudinal study, increased subjective sleepiness was associated with increased odds of developing depression, and objective change in MSL from ≥8 minutes to <8 minutes was associated with reduced odds of developing depression.64 Reasons for these paradoxical findings are unknown but may be related to use of a self-reported depression rating scale in these studies instead of structured interviews.

RECOGNIZING IDIOPATHIC HYPERSOMNIA IN PATIENTS WITH PSYCHIATRIC CONDITIONS

Before objective sleep testing, the key feature for recognizing idiopathic hypersomnia is EDS persisting for ≥3 months that cannot be explained by insufficient sleep, another sleep disorder, a psychiatric or medical disorder, or medication/substance use or withdrawal.1 Prominent symptoms including severe sleep inertia (historically known as “sleep drunkenness”), autonomic dysfunction, and LST should raise suspicion of idiopathic hypersomnia after excluding other possible causes of hypersomnia. Severe sleep inertia, involving prolonged confusion, slowness, irritability, and tendency to return to sleep after awakening, has been reported in 36%–66% of people with idiopathic hypersomnia.1,37,65 Among 173 participants (30 with narcolepsy, 62 idiopathic hypersomnia, 33 OSA, and 48 other [mainly psychiatric] hypersomnia) who performed an auditory target detection stimulation task before and after napping and during 2 intra-nap forced awakenings, sleep inertia was the best predictor of nonpsychiatric hypersomnia.66 In some series, autonomic dysfunction symptoms affected ≥50% of patients with idiopathic hypersomnia.36,67 Chronic LST is also a major symptom for some; ≥30% of people with idiopathic hypersomnia have TST ≥10 hours.1 Clinicians should consider that people may use words, such as “fatigue” and “tired,” to describe symptoms and should clarify whether they are experiencing increased need for sleep as opposed to feelings of low energy or needing rest.

Screening questionnaires can help identify candidates for objective sleep testing. The ESS assesses subjective EDS and sleep propensity in adults; ESS score >10 marks the threshold for pathologic sleepiness.68 The ESS for Children and Adolescents has been validated in children and adolescents 7–16 years of age.69 The IHSS is a 14-item self-reported measure of hypersomnolence symptoms (prolonged and unrefreshing daytime and nighttime sleep, impaired daytime alertness, and sleep inertia) that respond to idiopathic hypersomnia treatment.70 In a validation study that excluded patients with psychiatric comorbidities, an IHSS score of 22 was the optimal cutoff value for distinguishing untreated people with idiopathic hypersomnia from a control population; the use of the IHSS in a psychiatric population has not been reported.70

Differential Diagnosis

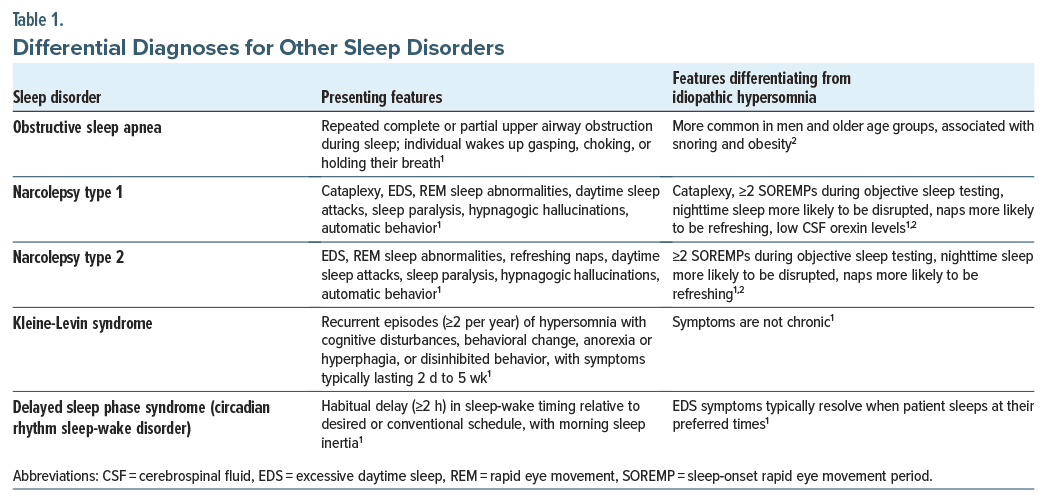

Other diagnoses that psychiatric clinicians should evaluate before referring people to a sleep specialist on suspicion of a sleep disorder include hypersomnia related to a psychiatric disorder, substance- or medication-induced sleep disorder, history of infection, and circadian rhythm sleep-wake disorders (Table 1).2,71 Individuals with idiopathic hypersomnia or other sleep disorders contributing to vegetative symptoms (eg, OSA) may appear to have “treatment-resistant” psychiatric conditions or hypersomnolence that persists despite improvement in other symptoms.4,21,72 The DSM-5-TR classification of hypersomnolence disorder (F51.11) has symptomatology very similar to that of idiopathic hypersomnia, with the critical difference that hypersomnolence disorder is diagnosed by subjective symptoms rather than objective sleep testing.20 When symptoms indicate hypersomnolence disorder, PSG/ MSLT is necessary to diagnose/rule out idiopathic hypersomnia and other sleep disorders.2 A common sleep disorder cause of hypersomnia in those with psychiatric disorders is OSA21; however, other sleep disorders including narcolepsy and DSPS are also associated with high rates of psychiatric comorbidities.73,74 DSM-5-TR guidelines recognize the challenge of differentiating hypersomnolence disorder from other psychiatric disorders that may involve hypersomnolence or fatigue and the possible bidirectional relationship between hypersomnolence and depressive symptoms.20 It is especially important to investigate what a person means by describing symptoms such as fatigue, tiredness, weakness, or sleepiness.

People with idiopathic hypersomnia and hypersomnolence related to psychiatric conditions may differ in objective sleep measures. Individuals with hypersomnia related to a psychiatric disorder (n = 23) had more sleep disturbance signs on nocturnal PSG (higher sleep latency, wakefulness after sleep onset, total wake time) and longer sleep latency during daytime naps than individuals with primary hypersomnia (based on DSM-IV criteria, superseded by hypersomnolence disorder in DSM-5-TR; n = 59).75 Individuals with MDD and comorbid hypersomnolence (n = 22) who underwent ad libitum PSG had longer sleep time and similar sleep efficiency versus healthy controls; a follow-up comparison of participants with both hypersomnolence and MDD (n = 22), hypersomnolence (n = 17) or MDD (n = 22) alone, or neither (control group; n = 22) found no difference in sleep macrostructure between people who had hypersomnolence with versus without MDD.76,77 However, these studies did not report MSLT results in people with MDD, so it is unknown how many met ICSD criteria for idiopathic hypersomnia.76,77 In a comparison of 15 people with idiopathic hypersomnia who denied having psychiatric symptoms and were not receiving treatment for a psychiatric disorder and 52 people with hypersomnia associated with psychiatric disorders validated by clinical interviews (including 11 people with current MDD and 34 people with MDD in remission), those diagnosed with idiopathic hypersomnia had significantly longer TST, greater sleep efficiency, and shorter MSL.78 Beck Depression Inventory–II scores were not significantly different between the 2 groups, further underscoring the unclear relationship between EDS and depression symptoms, whereas people in the idiopathic hypersomnia group reported more frequently relying on another person to help them wake up in the morning and had significantly higher rates of memory and concentration problems.

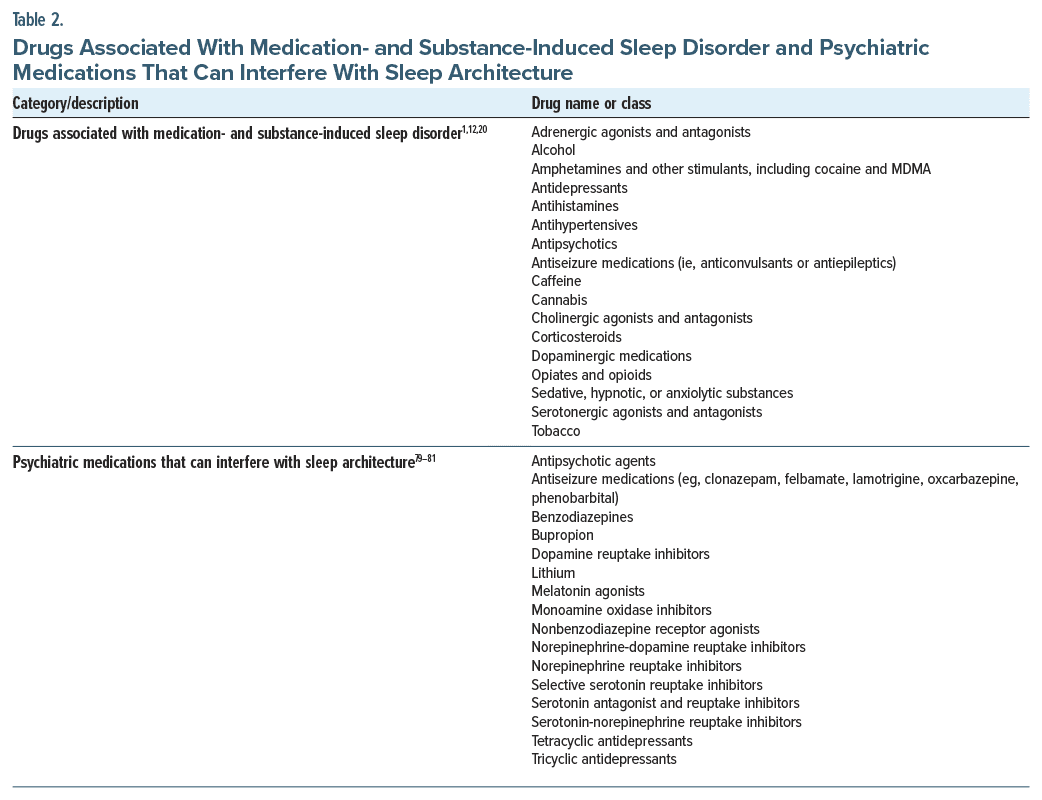

Substance- or medication-induced sleep disorder (DSM-5-TR) or hypersomnia caused by a drug or substance (ICSD-3-TR) is an important differential diagnosis to suspect when symptoms develop soon after exposure to/withdrawal from a medication/substance with known effects on sleep (Table 2).1,20 Conversely, medication/substance use changes may unmask idiopathic hypersomnia, as people with the condition may use substances to manage primary hypersomnia symptoms or secondary depression or anxiety symptoms surrounding the disease burden or incorrectly attribute their symptoms to ADHD based on the efficacy of stimulants in improving them.

Some infections and inflammatory diseases have hypersomnia or fatigue as an associated symptom—suggesting a possible mechanistic link with hypersomnia—and should be considered possible causes of EDS.82–84 COVID-19 infection has been associated with new-onset hypersomnolence, worsening of existing hypersomnolence, and increased prevalence of EDS and LST.85,86 EDS (along with depression and anxiety) is also a common symptom of fibromyalgia associated with greater pain, tenderness, and fatigue84 and can be the main presenting symptom of Epstein-Barr encephalitis.83 Brain fog is another common and persistent symptom of COVID-19 infection and immune/inflammatory disorders, in addition to idiopathic hypersomnia.87 Individuals with idiopathic hypersomnia also have been reported to have high rates of chronic fatigue syndrome (systemic exertional intolerance) and serologic markers of prior Epstein-Barr virus infection.88,89

Considerations for Objective Testing

A meta-analysis that used MSLT to assess reported hypersomnolence in people with psychiatric disorders found approximately 25% had MSLT <8 minutes.90 To facilitate referrals, psychiatric clinicians should consider developing a working relationship with a sleep center. In patients identified as potentially benefiting from objective sleep testing, a major consideration is the possible effect of psychiatric medications on PSG/ MSLT results. In a retrospective analysis of a sleep center population, people who tapered off REM sleep–suppressing antidepressants before MSLT (n = 121) were more likely to have ≥2 SOREMPs than people who continued taking (n = 53) or were not taking (n = 324) the drugs.91

The American Academy of Sleep Medicine (AASM) task force on MSLT and Maintenance of Wakefulness Test administration recommends people stop taking medications with alerting, sedating, or REM sleep–modulating properties ≥2 weeks before PSG/MSLT (Table 2).79 The task force suggests clinicians work with each patient to develop a medication management plan that will minimize disruptions to the patient’s life. If a patient is unable to discontinue medication that potentially affects sleep (eg, because of safety risks), all medications taken within 24 hours should be listed on the test report to aid in interpretation.79

MANAGEMENT OF IDIOPATHIC HYPERSOMNIA IN PATIENTS WITH PSYCHIATRIC CONDITIONS

Nonpharmacologic symptom management is often recommended for sleep disorders; however, evidence for the effectiveness of nonpharmacologic interventions for idiopathic hypersomnia is limited.92 People with self reported idiopathic hypersomnia (n = 129) or narcolepsy (n = 242) reported high utilization rates for nonpharmacologic interventions (eg, naps, exercise), but respondents with idiopathic hypersomnia generally reported lower effectiveness of these interventions.93 Planned naps may be ineffective for patients with idiopathic hypersomnia, particularly those with LST, owing to prominent sleep inertia on waking.94 Among surveyed individuals with idiopathic hypersomnia (n = 88), NT1 (n = 73), and NT2 (n = 58), the COVID-19 pandemic lockdown was associated with a significant decrease in ESS scores, and shifts to teleworking were associated with a significant decrease in ESS scores and increase in sleep time versus prelockdown measurements, suggesting that maintaining a more flexible sleep schedule could benefit patients with central disorders of hypersomnia.95 By discussing social and professional aspects of living with idiopathic hypersomnia with their patients, clinicians may identify additional support strategies, such as establishing accommodations with a patient’s school or employer, tailored to the individual’s specific needs.71,92

No randomized controlled trials of behavioral interventions have been reported for idiopathic hypersomnia or for central disorders of hypersomnolence in general.96 A novel telehealth-based cognitive behavioral therapy for hypersomnia improved depressive symptoms in 40% of participants (n = 23 adults with narcolepsy; n = 12 adults with idiopathic hypersomnia),96 and a study is currently assessing the effectiveness of a transdiagnostic sleep treatment—a combination of cognitive behavioral therapy for insomnia and chronotherapy—for people with hypersomnia, circadian rhythm disorders, or insomnia comorbid with bipolar disorder, MDD, or ADHD.97

People with idiopathic hypersomnia should be warned about driving while sleepy and advised to avoid driving during initiation of new treatments.71 Although consumer sleep technologies such as wearable sleep tracking devices cannot replace electroencephalography based measurements obtained during nocturnal PSG for the diagnosis of idiopathic hypersomnia, they may provide useful preliminary information about physical activity and time in bed.98

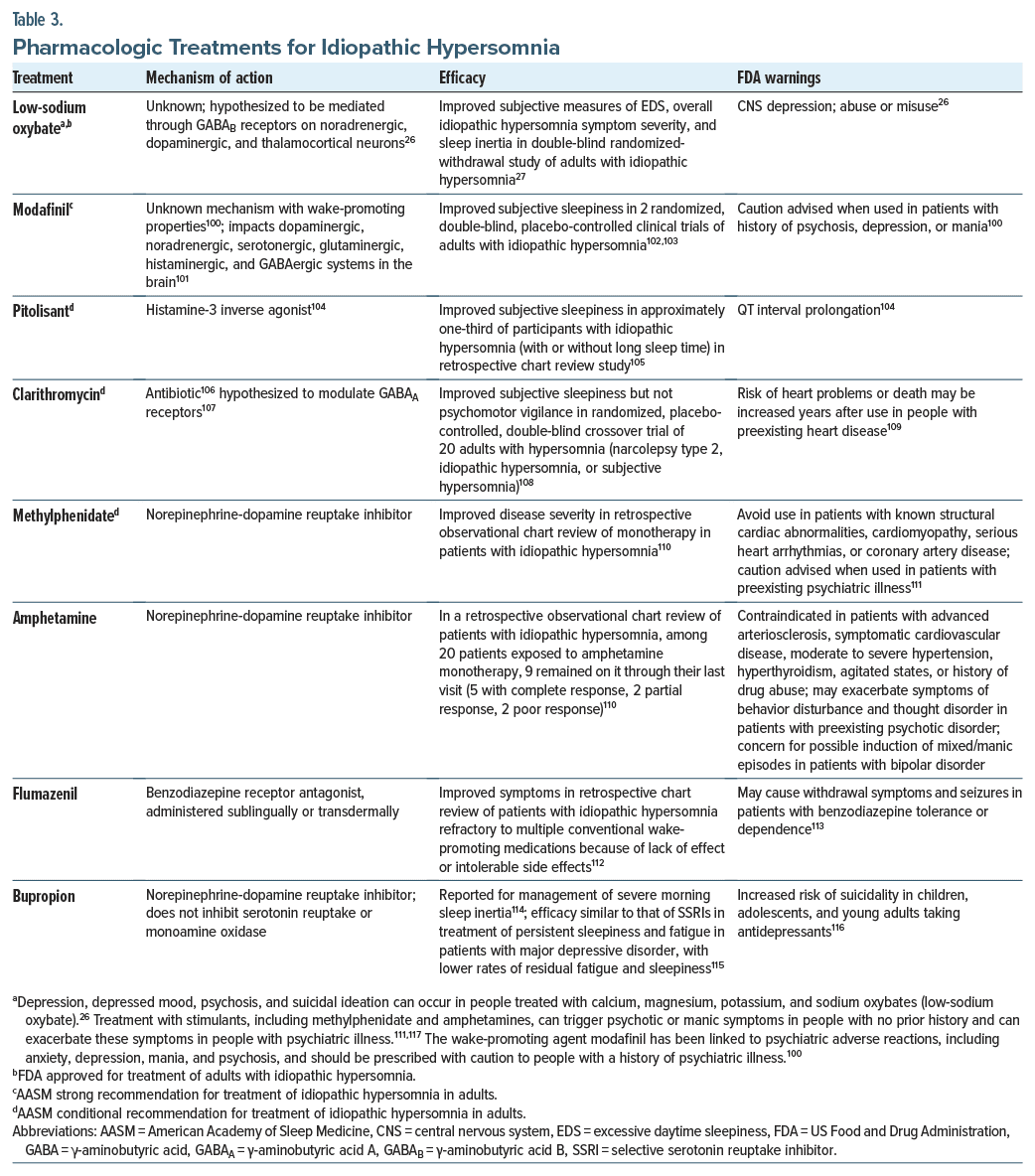

The 2021 AASM clinical practice guidelines recommend modafinil and, conditionally, clarithromycin, pitolisant, methylphenidate, and sodium oxybate for the treatment of adults with idiopathic hypersomnia, versus no treatment; however, as of August 2021, the only drug with US Food and Drug Administration approval for that indication is calcium, magnesium, potassium, and sodium oxybates (low-sodium oxybate).26,99 Given these medications are intended to act centrally via mechanisms similar to those affected in psychiatric conditions, potential effects on psychiatric symptoms should be considered. Notably, prescribing information for modafinil, methylphenidate, amphetamines, sodium oxybate, and low-sodium oxybate advises caution when treating people with a history of depression, psychosis, or mania because of possible emergence/exacerbation of psychiatric symptoms (Table 3).26,100,111,117,118 These treatments also carry a risk of abuse/misuse.26,100,111,117,118 The care of patients with psychiatric disorders and idiopathic hypersomnia is complex given the potential for sleep-related adverse effects of psychiatric medications and drug interactions. A caveat to consider in this review is that some of the data reported were derived from congress abstracts that may be limited in the information provided (ie, details on the patient population or study design). Multidisciplinary board meetings including clinicians from sleep medicine, psychiatry, neurology, psychology, and pharmacy have been proposed to foster collaborative sleep disorder management including idiopathic hypersomnia, particularly challenging cases such as those involving psychiatric comorbidities.119 Careful monitoring is required when initiating medications for idiopathic hypersomnia, as they may exacerbate psychiatric conditions. Participants with self-reported idiopathic hypersomnia (n = 75) who were using ≥1 commonly prescribed off-label prescription medication (eg, stimulants, wake-promoting agents, antidepressants) reported low treatment satisfaction and efficacy on the Treatment Satisfaction Questionnaire for Medication version II, and many experienced a high symptom burden despite use of off-label medications and other symptom management methods (eg, caffeine, planned naps, individual accommodations).120 Conversely, a randomized placebo-controlled study of low-sodium oxybate detected improvements in EDS, overall idiopathic hypersomnia symptom severity, and QoL.5,121 Whether medications that improve subjective/objective measures of EDS in people with idiopathic hypersomnia can positively impact comorbid depressive symptoms remains to be determined.

LONG-TERM OUTCOMES

Reported rates of spontaneous remission in individuals with objectively diagnosed idiopathic hypersomnia followed for ≥1 year range from 14%–33%.122–124 In a longitudinal analysis of 10 cases of probable idiopathic hypersomnia over a mean of 12.1 years (range, 3–17.8 years), 4 people experienced symptom remission, attributed in 1 person each to increased caffeine consumption, acetyl carnitine and melatonin supplementation, selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor treatment, and spontaneous remission with no identifiable cause.8 Clinicians should not assume people who stop attending follow-up appointments have experienced remission; dissatisfaction with treatment options should also be considered. In a survey of 290 people with physician diagnosed idiopathic hypersomnia, 40% of participants strongly or somewhat agreed with the statement “No treatments have improved my idiopathic hypersomnia symptoms at all.”4

Clinicians should consider a possible cumulative risk of comorbidities associated with idiopathic hypersomnia and a psychiatric diagnosis, as each is individually associated with increased risk of nonpsychiatric comorbidities, including cardiovascular, immune-related, and autoinflammatory disorders.7,125–129 Whether individuals with idiopathic hypersomnia plus ≥1 psychiatric disorders are at greater risk than those with any 1 diagnosis remains unclear. Psychiatric clinicians can advise people of the heightened risk of nonpsychiatric comorbidities and may consider referring them to other specialists or primary care providers if nonpsychiatric comorbidities are suspected.

Successful management of idiopathic hypersomnia can improve QoL.5,121 No studies have reported quantitatively on the benefit of sleep disorder management in populations with psychiatric conditions, but given the high psychosocial burden of idiopathic hypersomnia, it can be hypothesized that effective management of idiopathic hypersomnia (eg, improved functioning, daytime sleepiness, or sleep inertia) may positively impact psychiatric symptoms either directly or indirectly. In an inductive qualitative interview–based study of how 12 individuals with idiopathic hypersomnia experience and cope with their disease, most participants expressed the biggest consequence of the disease was lost time that could have been spent doing valued activities, which negatively affected their mood and life satisfaction.130 With treatment, people with idiopathic hypersomnia may have more time for relationships and healthy lifestyle choices, perform better at school/work, and even experience improved self-esteem.

CONCLUSION

The relationship between idiopathic hypersomnia and psychiatric disorders is complex and likely bidirectional. The prevalence of unrecognized and untreated idiopathic hypersomnia may be higher in psychiatric practice versus the overall population, raising the need for clinicians to remain aware of this rare condition.

Article Information

Published Online: June 2, 2025. https://doi.org/10.4088/JCP.24nr15718

© 2025 Physicians Postgraduate Press, Inc.

Submitted: December 5, 2024; accepted March 10, 2025.

To Cite: Chepke C, Benca RM, Cutler AJ, et al. Idiopathic hypersomnia: recognition and management in psychiatric practice. J Clin Psychiatry 2025;86(3):24nr15718.

Author Affiliations: Excel Psychiatric Associates, Huntersville, North Carolina (Chepke); Psychiatry and Behavioral Medicine, Wake Forest University School of Medicine, Winston-Salem, North Carolina (Benca); SUNY Upstate Medical University, Syracuse, New York (Cutler); Psychiatry and Behavioral Science, University of California San Francisco, San Francisco, California (Krystal); Department of Neurology, University of Washington School of Medicine, Seattle, Washington (Watson).

Corresponding Author: Craig Chepke, MD, DFAPA, Excel Psychiatric Associates, 10225 Hickorywood Hill Ave, Suite B, Huntersville, NC 28078 ([email protected]).

Author Contributions: All authors participated in collection and assembly of data, data analysis, data interpretation, manuscript preparation, manuscript review and revisions, and final approval of manuscript.

Relevant Financial Relationships: Dr Chepke: Advisory board: AbbVie, Acadia, Alkermes, Axsome, Biogen, Bristol Myers Squibb, Corium, Idorsia, Intra-Cellular, Johnson & Johnson, Lundbeck, Moderna, Neurocrine, Noven, Otsuka, Sage, Sumitomo, Teva; advisory board (spouse): Bristol Myers Squibb, Otsuka; consultant: AbbVie, Acadia, Alkermes, Axsome, Biogen, Boehringer Ingelheim, Bristol Myers Squibb, Corium, Intra-Cellular, Johnson & Johnson, Lundbeck, MedinCell, Moderna, Neurocrine, Noven, Otsuka, Sage, Sumitomo, Supernus, Teva; research/grant support: Acadia, Axsome, Harmony, Neurocrine, Teva; speakers bureau: AbbVie, Acadia, Alkermes, Axsome, Bristol Myers Squibb, Corium, Intra-Cellular, Johnson & Johnson, Lundbeck, Merck, Neurocrine, Noven, Otsuka, Sumitomo, Teva; Stocks/Ownership Interest: none. Dr Benca: Consultant: Alkermes, Eisai, Idorsia, Haleon, Jazz, Merck, Sage; research/grant support: Eisai. Dr Cutler: Consultant and advisory board: AbbVie, Acadia, Alfasigma, Alkermes, Anavex Life Sciences, Axsome, Biogen, BioXcel, Boehringer Ingelheim, Brii Biosciences, Bristol Myers Squibb, Cerevel, Chase Therapeutics, Cognitive Research, Corium, Delpor, Evolution Research Group, 4M Therapeutics, Intra-Cellular Therapies, Ironshore Pharmaceuticals, Janssen/J&J, Jazz Pharmaceuticals, Karuna, LivoNova, Lundbeck, Luye Pharma, Maplight Therapeutics, MedAvante-ProPhase, Mentavi, Neumora, Neurocrine, Neuroscience Education Institute, NeuroSigma, Noven, Otsuka, PureTech Health, Relmada, Reviva, Sage, Sumitomo Pharma America, Sunovion, Supernus, Teva, Thynk, Tris Pharma, Vanda Pharmaceuticals, VistaGen, VivoSense; speakers bureau: AbbVie, Acadia, Alfasigma, Alkermes, Axsome, BioXcel, Corium, Intra-Cellular Therapies, Ironshore Pharmaceuticals, Janssen, Lundbeck, Neurocrine, Noven, Otsuka, Sunovion, Supernus, Teva, Tris Pharma, Vanda Pharmaceuticals; stock options: 4M Therapeutics, Relmada; data safety monitoring board: Alar Pharma, COMPASS Pathways, Freedom Biosciences, Pain Therapeutics. Dr Krystal: Research grants: Janssen Pharmaceuticals, Axsome Pharmaceutics, Attune, Harmony, Neurocrine Biosciences, Reveal Biosensors, The Ray and Dagmar Dolby Family Fund, National Institutes of Health; consulting: Axsome Therapeutics, Big Health, Eisai, Evecxia, Harmony Biosciences, Idorsia, Janssen Pharmaceuticals, Jazz Pharmaceuticals, Merck, Neurocrine Biosciences, Neurawell, Otsuka Pharmaceuticals, Sage, Takeda; stock options: Neurawell, Big-Health. Dr Watson: Consultant: Idorsia, Jazz Pharmaceuticals, Harmony Biosciences, Takeda.

Funding/Support: This review was sponsored by Jazz Pharmaceuticals (Philadelphia, PA, US).

Role of the Sponsor: Although Jazz Pharmaceuticals was involved in the review of the manuscript, the content of this manuscript, the ultimate interpretation, and the decision to submit it for publication were made by the authors independently.

Acknowledgments: Under the direction of the authors, Peloton Advantage, LLC (an OPEN Health company), employees Emilie Croisier, PhD, and Stephanie Phan, PharmD, provided medical writing support and Christopher Jaworski, BA, provided editorial support, which were funded by Jazz Pharmaceuticals.

ORCID: Craig Chepke: https://orcid.org/0000-0002-4873-4770; Andrew Cutler: https://orcid.org/0000-0001-5800-0378

Clinical Points

- Given the increased incidence of psychiatric comorbidities among people with idiopathic hypersomnia compared with the general population, psychiatric clinicians can have a positive impact on the lives of these individuals by having greater knowledge of the diagnosis and appropriate management of idiopathic hypersomnia.

- Patients with idiopathic hypersomnia present with symptoms of excessive daytime sleepiness and sleep inertia that may be assessed via validated questionnaires. The differential diagnosis may include hypersomnia stemming from other causes, such as psychiatric conditions, substance- or medication-induced sleep disorders, and other sleep disorders. Referral to a sleep specialist may be appropriate, and multidisciplinary collaboration can help improve patient care.

- Given the potential impact of medications used in the management of idiopathic hypersomnia on psychiatric symptoms and vice versa, patients receiving treatment for these disorders should be carefully monitored for changes in symptoms.

References (130)

- American Academy of Sleep Medicine. International Classification of Sleep Disorders – Third Edition, Text Revision. American Academy of Sleep Medicine; 2023.

- Dauvilliers Y, Bogan RK, Arnulf I, et al. . Clinical considerations for the diagnosis of idiopathic hypersomnia Recognition and Management in Psychiatric Practice. Sleep Med Rev. 2022;66:101709. PubMed CrossRef

- Stevens J, Schneider LD, Husain A, et al. . Impairment in functioning and quality of life in patients with idiopathic hypersomnia: the Real World Idiopathic Hypersomnia Outcomes Study (ARISE) Recognition and Management in Psychiatric Practice. Nat Sci Sleep. 2023;15:593–606. PubMed CrossRef

- Whalen M, Roy B, Steininger T, et al. . Patient perspective on idiopathic hypersomnia: impact on quality of life and satisfaction with the diagnostic process and management [poster 157] Recognition and Management in Psychiatric Practice. Presented at: Annual Meeting of the Associated Professional Sleep Societies; June 4–8, 2022; Charlotte, NC.

- Dauvilliers Y, Arnulf I, Foldvary-Schaefer N, et al. . Safety and efficacy of lower-sodium oxybate in adults with idiopathic hypersomnia: a phase 3, placebo-controlled, double-blind, randomised withdrawal study Recognition and Management in Psychiatric Practice. Lancet Neurol. 2022;21(1):53–65. PubMed CrossRef

- Nevsimalova S, Skibova J, Galuskova K, et al. . Central disorders of hypersomnolence: association with fatigue, depression and sleep inertia prevailing in women Recognition and Management in Psychiatric Practice. Brain Sci. 2022;12(11):1491. PubMed CrossRef

- Lillaney P, Saad R, Profant D, et al. . Real-World Idiopathic Hypersomnia Total Health Model (RHYTHM): clinical burden of patients with idiopathic hypersomnia [poster 250] Recognition and Management in Psychiatric Practice. Presented at: Annual Meeting of the Associated Professional Sleep Societies; June 3–7; Indianapolis, IN.

- Plante DT, Hagen EW, Barnet JH, et al. . Prevalence and course of idiopathic hypersomnia in the Wisconsin Sleep Cohort study Recognition and Management in Psychiatric Practice. Neurology. 2024;102(2):e207994. PubMed CrossRef

- Ohayon MM, Dauvilliers Y, and Reynolds CF. Operational definitions and algorithms for excessive sleepiness in the general population: implications for DSM-5 nosology Recognition and Management in Psychiatric Practice. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2012;69(1):71–79. PubMed CrossRef

- Saad R, Black J, Bogan RK, et al. . Diagnosed prevalence of idiopathic hypersomnia among adults in the United States [poster] Recognition and Management in Psychiatric Practice. Presented at: Annual Meeting of the Academy of Managed Care Pharmacy Nexus; October 16–19; Orlando, FL.

- Acquavella J, Mehra R, Bron M, et al. . Prevalence of narcolepsy, other sleep disorders, and diagnostic tests from 2013–2016: insured patients actively seeking care Recognition and Management in Psychiatric Practice. J Clin Sleep Med. 2020;16(8):1255–1263. PubMed CrossRef

- Sowa NA. Idiopathic hypersomnia and hypersomnolence disorder: a systematic review of the literature Recognition and Management in Psychiatric Practice. Psychosomatics. 2016;57(2):152–164. PubMed CrossRef

- Plante DT, Epstein LJ, Fields BG, et al. . Competency-based sleep medicine fellowships: addressing workforce needs and enhancing educational quality Recognition and Management in Psychiatric Practice. J Clin Sleep Med. 2020;16(1):137–141. PubMed CrossRef

- Roth T, Dauvilliers Y, Mignot E, et al. . Disrupted nighttime sleep in narcolepsy Recognition and Management in Psychiatric Practice. J Clin Sleep Med. 2013;9(9):955–965. PubMed CrossRef

- Jaussent I, Morin CM, Ivers H, et al. . Natural history of excessive daytime sleepiness: a population-based 5-year longitudinal study Recognition and Management in Psychiatric Practice. Sleep. 2020;43(3):zsz249. PubMed CrossRef

- Jaussent I, Morin CM, Ivers H, et al. . Incidence, worsening and risk factors of daytime sleepiness in a population-based 5-year longitudinal study Recognition and Management in Psychiatric Practice. Sci Rep. 2017;7(1):1372. PubMed CrossRef

- Fernandez-Mendoza J, Vgontzas AN, Kritikou I, et al. . Natural history of excessive daytime sleepiness: role of obesity, weight loss, depression, and sleep propensity Recognition and Management in Psychiatric Practice. Sleep. 2015;38(3):351–360. PubMed CrossRef

- Kaplan KA, and Harvey AG. Hypersomnia across mood disorders: a review and synthesis Recognition and Management in Psychiatric Practice. Sleep Med Rev. 2009;13(4):275–285. PubMed CrossRef

- Plante DT. Hypersomnia in mood disorders: a rapidly changing landscape Recognition and Management in Psychiatric Practice. Curr Sleep Med Rep. 2015;1(2):122–130. PubMed CrossRef

- American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fifth Edition, Text Revision. American Psychiatric Association; 2022.

- Benca RM, Krystal A, Chepke C, et al. . Recognition and management of obstructive sleep apnea in psychiatric practice Recognition and Management in Psychiatric Practice. J Clin Psychiatry. 2023;84(2):22r14521. PubMed CrossRef

- Walker WH, Walton JC, DeVries AC, et al. . Circadian rhythm disruption and mental health Recognition and Management in Psychiatric Practice. Transl Psychiatry. 2020;10(1):28. PubMed CrossRef

- Mairesse O, Damen V, Newell J, et al. . The Brugmann Fatigue Scale: an analogue to the Epworth Sleepiness Scale to measure behavioral rest propensity Recognition and Management in Psychiatric Practice. Behav Sleep Med. 2019;17(4):437–458. PubMed CrossRef

- Whalen M, Roy B, Steininger T, et al. . Physician perspective on idiopathic hypersomnia: awareness, diagnosis, and impact on patients [poster 156] Recognition and Management in Psychiatric Practice. Presented at: Annual Meeting of the Associated Professional Sleep Societies; June 4–8, 2022; Charlotte, NC.

- Rye DB, Bliwise DL, Parker K, et al. . Modulation of vigilance in the primary hypersomnias by endogenous enhancement of GABAA receptors Recognition and Management in Psychiatric Practice. Sci Transl Med. 2012;4(161):161ra151. PubMed CrossRef

- Xywav® (Calcium, Magnesium, Potassium, and Sodium Oxybates) Oral Solution, CIII [Prescribing Information]. Jazz Pharmaceuticals, Inc.; 2023.

- Thorpy MJ, Arnulf I, Foldvary-Schaefer N, et al. . Efficacy and safety of lower-sodium oxybate in an open-label titration period of a phase 3 clinical study in adults with idiopathic hypersomnia Recognition and Management in Psychiatric Practice. Nat Sci Sleep. 2022;14:1901–1917. PubMed CrossRef

- Pardi D, and Black J. gamma-Hydroxybutyrate/sodium oxybate: neurobiology, and impact on sleep and wakefulness Recognition and Management in Psychiatric Practice. CNS drugs. 2006;20(12):993–1018. PubMed CrossRef

- Vernet C, and Arnulf I. Idiopathic hypersomnia with and without long sleep time: a controlled series of 75 patients Recognition and Management in Psychiatric Practice. Sleep. 2009;32(6):753–759. PubMed CrossRef

- Landzberg D, and Trotti LM. Is idiopathic hypersomnia a circadian rhythm disorder? Recognition and Management in Psychiatric Practice Curr Sleep Med Rep. 2019;5(4):201–206. PubMed CrossRef

- Scheer FA, Shea TJ, Hilton MF, et al. . An endogenous circadian rhythm in sleep inertia results in greatest cognitive impairment upon awakening during the biological night Recognition and Management in Psychiatric Practice. J Biol Rhythms. 2008;23(4):353–361. PubMed CrossRef

- Lippert J, Halfter H, Heidbreder A, et al. . Altered dynamics in the circadian oscillation of clock genes in dermal fibroblasts of patients suffering from idiopathic hypersomnia Recognition and Management in Psychiatric Practice. PloS one. 2014;9(1):e85255. PubMed CrossRef

- Horovitz SG, Braun AR, Carr WS, et al. . Decoupling of the brain’s default mode network during deep sleep Recognition and Management in Psychiatric Practice. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2009;106(27):11376–11381. PubMed CrossRef

- Boucetta S, Montplaisir J, Zadra A, et al. . Altered regional cerebral blood flow in idiopathic hypersomnia Recognition and Management in Psychiatric Practice. Sleep. 2017;40(10).

- Pomares FB, Boucetta S, Lachapelle F, et al. . Beyond sleepy: structural and functional changes of the default-mode network in idiopathic hypersomnia Recognition and Management in Psychiatric Practice. Sleep. 2019;42(11):zsz156. PubMed CrossRef

- Miglis MG, Schneider L, Kim P, et al. . Frequency and severity of autonomic symptoms in idiopathic hypersomnia Recognition and Management in Psychiatric Practice. J Clin Sleep Med. 2020;16(5):749–756. PubMed CrossRef

- Vernet C, Leu-Semenescu S, Buzare MA, et al. . Subjective symptoms in idiopathic hypersomnia: beyond excessive sleepiness Recognition and Management in Psychiatric Practice. J Sleep Res. 2010;19(4):525–534. PubMed CrossRef

- Sforza E, Roche F, Barthélémy JC, et al. . Diurnal and nocturnal cardiovascular variability and heart rate arousal response in idiopathic hypersomnia Recognition and Management in Psychiatric Practice. Sleep Med. 2016;24:131–136. PubMed CrossRef

- Fogaça MV, and Duman RS. Cortical GABAergic dysfunction in stress and depression: new insights for therapeutic interventions Recognition and Management in Psychiatric Practice. Front Cell Neurosci. 2019;13:87.

- Belujon P, and Grace AA. Dopamine system dysregulation in major depressive disorders Recognition and Management in Psychiatric Practice. Int J Neuropsychopharmacol. 2017;20(12):1036–1046. PubMed CrossRef

- Moret C, and Briley M. The importance of norepinephrine in depression Recognition and Management in Psychiatric Practice. Neuropsychiatr Dis Treat. 2011;7(suppl 1):9–13. PubMed CrossRef

- Kivelä L, Papadopoulos MR, and Antypa N. Chronotype and psychiatric disorders Recognition and Management in Psychiatric Practice. Curr Sleep Med Rep. 2018;4(2):94–103. PubMed

- Briley PM, Webster L, Boutry C, et al. . Resting-state functional connectivity correlates of anxiety co-morbidity in major depressive disorder Recognition and Management in Psychiatric Practice. Neurosci Biobehav Rev. 2022;138:104701. PubMed CrossRef

- Mohan A, Roberto AJ, Mohan A, et al. . The significance of the default mode network (DMN) in neurological and neuropsychiatric disorders: a review Recognition and Management in Psychiatric Practice. Yale J Biol Med. 2016;89(1):49–57. PubMed

- Ramesh A, Nayak T, Beestrum M, et al. . Heart rate variability in psychiatric disorders: a systematic review Recognition and Management in Psychiatric Practice. Neuropsychiatr Dis Treat. 2023;19:2217–2239. PubMed CrossRef

- Alvares GA, Quintana DS, Hickie IB, et al. . Autonomic nervous system dysfunction in psychiatric disorders and the impact of psychotropic medications: a systematic review and meta-analysis Recognition and Management in Psychiatric Practice. J Psychiatry Neurosci. 2016;41(2):89–104. PubMed CrossRef

- Watson NF, Harden KP, Buchwald D, et al. . Sleep duration and depressive symptoms: a gene-environment interaction Recognition and Management in Psychiatric Practice. Sleep. 2014;37(2):351–358. PubMed CrossRef

- Lessov-Schlaggar CN, Bliwise DL, Krasnow RE, et al. . Genetic association of daytime sleepiness and depressive symptoms in elderly men Recognition and Management in Psychiatric Practice. Sleep. 2008;31(8):1111–1117. PubMed

- Saad R, Prince P, Taylor B, et al. . Characteristics of adults newly diagnosed with idiopathic hypersomnia in the United States Recognition and Management in Psychiatric Practice. Sleep Epidemiol. 2023;3:100059. CrossRef

- Bollu P, Mekala H, Sivaraman M, et al. . Increased prevalence of psychiatric comorbidities in idiopathic hypersomnia compared with narcolepsy [abstract 0684] Recognition and Management in Psychiatric Practice. Sleep. 2016;39(suppl 1):A244.

- Lopez R, Micoulaud-Franchi JA, Camodeca L, et al. . Association of inattention, hyperactivity, and hypersomnolence in two clinic-based adult cohorts Recognition and Management in Psychiatric Practice. J Atten Disord. 2020;24(4):555–564. PubMed CrossRef

- Dauvilliers Y, Paquereau J, Bastuji H, et al. . Psychological health in central hypersomnias: the French Harmony study Recognition and Management in Psychiatric Practice. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2009;80(6):636–641. PubMed CrossRef

- Heidbreder A, Bellingrath S, Broer S, et al. . Atypical depression and idiopathic hypersomnia distinct disorders? [abstract P580] Recognition and Management in Psychiatric Practice. J Sleep Res. 2016;25(suppl 1):273–274.

- Dodson C, Spruyt K, Considine C, et al. . Hyperactivity in patients with narcolepsy and idiopathic hypersomnia: an exploratory study Recognition and Management in Psychiatric Practice. Sleep Sci Pract. 2023;7:6. PubMed CrossRef

- Walz JC, Magalhães PV, Reckziegel R, et al. . Daytime sleepiness, sleep disturbance and functioning impairment in bipolar disorder Recognition and Management in Psychiatric Practice. Acta Neuropsychiatr. 2013;25(2):101–104. PubMed CrossRef

- Tsuno N, Jaussent I, Dauvilliers Y, et al. . Determinants of excessive daytime sleepiness in a French community-dwelling elderly population Recognition and Management in Psychiatric Practice. J Sleep Res. 2007;16(4):364–371. PubMed CrossRef

- Hein M, Lanquart JP, Loas G, et al. . Prevalence and risk factors of excessive daytime sleepiness in major depression: a study with 703 individuals referred for polysomnography Recognition and Management in Psychiatric Practice. J Affect Disord. 2019;243:23–32. PubMed CrossRef

- Boz S, Lanquart JP, Mungo A, et al. . Risk of excessive daytime sleepiness associated to major depression in adolescents Recognition and Management in Psychiatric Practice. Psychiatr Q. 2021;92(4):1473–1488. PubMed CrossRef

- Cook JD, Rumble ME, and Plante DT. Identifying subtypes of hypersomnolence disorder: a clustering analysis Recognition and Management in Psychiatric Practice. Sleep Med. 2019;64:71–76. PubMed CrossRef

- Breslau N, Roth T, Rosenthal L, et al. . Sleep disturbance and psychiatric disorders: a longitudinal epidemiological study of young adults Recognition and Management in Psychiatric Practice. Biol Psychiatry. 1996;39(6):411–418. PubMed CrossRef

- Scott J, Kallestad H, Vedaa O, et al. . Sleep disturbances and first onset of major mental disorders in adolescence and early adulthood: a systematic review and meta-analysis Recognition and Management in Psychiatric Practice. Sleep Med Rev. 2021;57:101429. PubMed CrossRef

- Denton EJ, Barnes M, Churchward T, et al. . Mood disorders are highly prevalent in patients investigated with a multiple sleep latency test Recognition and Management in Psychiatric Practice. Sleep Breath. 2018;22(2):305–309. PubMed CrossRef

- Plante DT, Finn LA, Hagen EW, et al. . Subjective and objective measures of hypersomnolence demonstrate divergent associations with depression among participants in the Wisconsin Sleep Cohort Study Recognition and Management in Psychiatric Practice. J Clin Sleep Med. 2016;12(4):571–578. PubMed CrossRef

- Plante DT, Finn LA, Hagen EW, et al. . Longitudinal associations of hypersomnolence and depression in the Wisconsin Sleep Cohort Study Recognition and Management in Psychiatric Practice. J Affect Disord. 2017;207:197–202. PubMed CrossRef

- Trotti LM. Waking up is the hardest thing I do all day: sleep inertia and sleep drunkenness Recognition and Management in Psychiatric Practice. Sleep Med Rev. 2017;35:76–84. PubMed CrossRef

- Peter-Derex L, Perrin F, Petitjean T, et al. . Discriminating neurological from psychiatric hypersomnia using the forced awakening test Recognition and Management in Psychiatric Practice. Neurophysiol Clin. 2013;43(3):171–179. PubMed CrossRef

- Bassetti C, and Aldrich MS. Idiopathic hypersomnia. A series of 42 patients Recognition and Management in Psychiatric Practice. Brain. 1997;120(pt 8):1423–1435. PubMed

- Johns MW. A new method for measuring daytime sleepiness: the Epworth Sleepiness Scale Recognition and Management in Psychiatric Practice. Sleep. 1991;14(6):540–545. PubMed CrossRef

- Wang YG, Menno D, Chen A, et al. . Validation of the Epworth Sleepiness Scale for Children and Adolescents (ESS-CHAD) questionnaire in pediatric patients with narcolepsy with cataplexy aged 7–16 years Recognition and Management in Psychiatric Practice. Sleep Med. 2022;89:78–84. PubMed CrossRef

- Dauvilliers Y, Evangelista E, Barateau L, et al. . Measurement of symptoms in idiopathic hypersomnia: the idiopathic hypersomnia severity scale Recognition and Management in Psychiatric Practice. Neurology. 2019;92(15):e1754–e1762. PubMed CrossRef

- Leu-Semenescu S, Quera-Salva MA, and Dauvilliers Y. French consensus. Idiopathic hypersomnia: investigations and follow-up Recognition and Management in Psychiatric Practice. Rev Neurol (Paris). 2017;173(1–2):32–37. PubMed CrossRef

- McIntyre RS, Alsuwaidan M, Baune BT, et al. . Treatment-resistant depression: definition, prevalence, detection, management, and investigational interventions Recognition and Management in Psychiatric Practice. World Psychiatry. 2023;22(3):394–412. PubMed CrossRef

- Black J, Reaven NL, Funk SE, et al. . Medical comorbidity in narcolepsy: findings from the Burden of Narcolepsy Disease (BOND) study Recognition and Management in Psychiatric Practice. Sleep Med. 2017;33:13–18. PubMed CrossRef

- Futenma K, Takaesu Y, Komada Y, et al. . Delayed sleep-wake phase disorder and its related sleep behaviors in the young generation Recognition and Management in Psychiatric Practice. Front Psychiatry. 2023;14:1174719. PubMed CrossRef

- Vgontzas AN, Bixler EO, Kales A, et al. . Differences in nocturnal and daytime sleep between primary and psychiatric hypersomnia: diagnostic and treatment implications Recognition and Management in Psychiatric Practice. Psychosom Med. 2000;62(2):220–226. PubMed CrossRef

- Plante DT, Cook JD, and Goldstein MR. Objective measures of sleep duration and continuity in major depressive disorder with comorbid hypersomnolence: a primary investigation with contiguous systematic review and meta-analysis Recognition and Management in Psychiatric Practice. J Sleep Res. 2017;26(3):255–265. PubMed CrossRef

- Plante DT, Cook JD, Barbosa LS, et al. . Establishing the objective sleep phenotype in hypersomnolence disorder with and without comorbid major depression Recognition and Management in Psychiatric Practice. Sleep. 2019;42(6):zsz060. PubMed CrossRef

- Bušková J, Novák T, Miletínová E, et al. . Self-reported symptoms and objective measures in idiopathic hypersomnia and hypersomnia associated with psychiatric disorders: a prospective cross-sectional study Recognition and Management in Psychiatric Practice. J Clin Sleep Med. 2022;18(3):713–720.

- Krahn LE, Arand DL, Avidan AY, et al. . Recommended protocols for the Multiple Sleep Latency Test and Maintenance of Wakefulness Test in adults: guidance from the American Academy of Sleep Medicine Recognition and Management in Psychiatric Practice. J Clin Sleep Med. 2021;17(12):2489–2498. PubMed CrossRef

- Hutka P, Krivosova M, Muchova Z, et al. . Association of sleep architecture and physiology with depressive disorder and antidepressants treatment Recognition and Management in Psychiatric Practice. Int J Mol Sci. 2021;22(3):1333. PubMed CrossRef

- Liguori C, Toledo M, and Kothare S. Effects of anti-seizure medications on sleep architecture and daytime sleepiness in patients with epilepsy: a literature review Recognition and Management in Psychiatric Practice. Sleep Med Rev. 2021;60:101559. PubMed CrossRef

- Khosla S, Cheung J, Gurubhagavatula I, et al. . Sleep assessment in long COVID clinics: a necessary tool for effective management Recognition and Management in Psychiatric Practice. Neurol Clin Pract. 2023;13(1):e200079. PubMed CrossRef

- Zhao H, Zhang X, Yang H, et al. . Epstein-Barr virus encephalitis with excessive daytime sleepiness as the main manifestation: two case reports Recognition and Management in Psychiatric Practice. Medicine (Baltimore). 2022;101(34):e30327. PubMed CrossRef

- Sarzi-Puttini P, Rizzi M, Andreoli A, et al. . Hypersomnolence in fibromyalgia syndrome Recognition and Management in Psychiatric Practice. Clin Exp Rheumatol. 2002;20(1):69–72. PubMed

- Dvořáková T, Měrková R, and Bušková J. Sleep disorders after COVID-19 in Czech population: post-lockdown national online survey Recognition and Management in Psychiatric Practice. Sleep Med X. 2023;6:100087.

- Sarkanen T, Partinen M, Bjorvatn B, et al. . Association between hypersomnolence and the COVID-19 pandemic: the international COVID-19 Sleep Study (ICOSS) Recognition and Management in Psychiatric Practice. Sleep Med. 2023;107:108–115. PubMed CrossRef

- Rosenberg R, Thorpy MJ, Doghramji K, et al. . Brain fog in central disorders of hypersomnolence: a review Recognition and Management in Psychiatric Practice. J Clin Sleep Med. 2024;20(4):643–651. PubMed CrossRef

- Sforza E, Hupin D, and Roche F. Mononucleosis: a possible cause of idiopathic hypersomnia Recognition and Management in Psychiatric Practice. Front Neurol. 2018;9:922. PubMed CrossRef

- Maness C, Saini P, Bliwise DL, et al. . Systemic exertion intolerance disease/chronic fatigue syndrome is common in sleep centre patients with hypersomnolence: a retrospective pilot study Recognition and Management in Psychiatric Practice. J Sleep Res. 2019;28(3):e12689. PubMed CrossRef

- Plante DT. Sleep propensity in psychiatric hypersomnolence: a systematic review and meta-analysis of multiple sleep latency test findings Recognition and Management in Psychiatric Practice. Sleep Med Rev. 2017;31:48–57. PubMed CrossRef

- Kolla BP, Jahani Kondori M, Silber MH, et al. . Advance taper of antidepressants prior to multiple sleep latency testing increases the number of sleep-onset rapid eye movement periods and reduces mean sleep latency Recognition and Management in Psychiatric Practice. J Clin Sleep Med. 2020;16(11):1921–1927. PubMed CrossRef

- Schinkelshoek MS, Fronczek R, and Lammers GJ. Update on the treatment of idiopathic hypersomnia Recognition and Management in Psychiatric Practice. Curr Sleep Med Rep. 2019;5(4):207–214. CrossRef

- Neikrug AB, Crawford MR, and Ong JC. Behavioral sleep medicine services for hypersomnia disorders: a survey study Recognition and Management in Psychiatric Practice. Behav Sleep Med. 2017;15(2):158–171. PubMed CrossRef

- Arnulf I, Thomas R, Roy A, et al. . Update on the treatment of idiopathic hypersomnia: progress, challenges, and expert opinion Recognition and Management in Psychiatric Practice. Sleep Med Rev. 2023;69:101766. PubMed CrossRef

- Nigam M, Hippolyte A, Dodet P, et al. . Sleeping through a pandemic: impact of COVID-19-related restrictions on narcolepsy and idiopathic hypersomnia Recognition and Management in Psychiatric Practice. J Clin Sleep Med. 2022;18(1):255–263. PubMed CrossRef

- Ong JC, Dawson SC, Mundt JM, et al. . Developing a cognitive behavioral therapy for hypersomnia using telehealth: a feasibility study Recognition and Management in Psychiatric Practice. J Clin Sleep Med. 2020;16(12):2047–2062. PubMed CrossRef

- Kragh M, Dyrberg H, Speed M, et al. . The efficacy of a transdiagnostic sleep intervention for outpatients with sleep problems and depression, bipolar disorder, or attention deficit disorder: study protocol for a randomized controlled trial Recognition and Management in Psychiatric Practice. Trials. 2024;25(1):57. PubMed CrossRef

- Cook JD, Eftekari SC, Dallmann E, et al. . Ability of the Fitbit Alta HR to quantify and classify sleep in patients with suspected central disorders of hypersomnolence: a comparison against polysomnography Recognition and Management in Psychiatric Practice. J Sleep Res. 2019;28(4):e12789. PubMed CrossRef

- Maski K, Trotti LM, Kotagal S, et al. . Treatment of central disorders of hypersomnolence: an American Academy of Sleep Medicine clinical practice guideline Recognition and Management in Psychiatric Practice. J Clin Sleep Med. 2021;17(9):1881–1893. PubMed CrossRef

- Provigil [Package Insert]. Teva Pharmaceuticals; 2018.

- Minzenberg MJ, and Carter CS. Modafinil: a review of neurochemical actions and effects on cognition Recognition and Management in Psychiatric Practice. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2008;33(7):1477–1502. PubMed CrossRef

- Mayer G, Benes H, Young P, et al. . Modafinil in the treatment of idiopathic hypersomnia without long sleep time—a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled study Recognition and Management in Psychiatric Practice. J Sleep Res. 2015;24(1):74–81. PubMed CrossRef

- Inoue Y, Tabata T, and Tsukimori N. Efficacy and safety of modafinil in patients with idiopathic hypersomnia without long sleep time: a multicenter, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled, parallel-group comparison study Recognition and Management in Psychiatric Practice. Sleep Med. 2021;80:315–321. PubMed CrossRef

- Wakix [Package Insert]. Harmony Biosciences; 2022.

- Leu-Semenescu S, Nittur N, Golmard JL, et al. . Effects of pitolisant, a histamine H3 inverse agonist, in drug-resistant idiopathic and symptomatic hypersomnia: a chart review Recognition and Management in Psychiatric Practice. Sleep Med. 2014;15(6):681–687. PubMed CrossRef

- Clarithromycin [Package Insert]. Aurobindo Pharma Limited; 2023.

- Trotti LM, Saini P, Freeman AA, et al. . Improvement in daytime sleepiness with clarithromycin in patients with GABA-related hypersomnia: clinical experience Recognition and Management in Psychiatric Practice. J Psychopharmacol. 2014;28(7):697–702. PubMed CrossRef

- Trotti LM, Saini P, Bliwise DL, et al. . Clarithromycin in γ-aminobutyric acid-related hypersomnolence: a randomized, crossover trial Recognition and Management in Psychiatric Practice. Ann Neurol. 2015;78(3):454–465. PubMed CrossRef

- US Food and Drug Administration. FDA drug safety communication: FDA review finds additional data supports the potential for increased long-term risks with antibiotic clarithromycin (Biaxin) in patients with heart disease Recognition and Management in Psychiatric Practice. 2018. Accessed February 16, 2023. https://www.fda.gov/drugs/drug-safety-and-availability/fda-drug-safety-communication-fda-review-finds-additional-data-supports-potential-increased-long

- Ali M, Auger RR, Slocumb NL, et al. . Idiopathic hypersomnia: clinical features and response to treatment Recognition and Management in Psychiatric Practice. J Clin Sleep Med. 2009;5(6):562–568. PubMed

- Ritalin [Package Insert]. Novartis Pharmaceuticals Corporation; 2019.

- Trotti LM, Saini P, Koola C, et al. . Flumazenil for the treatment of refractory hypersomnolence: clinical experience with 153 patients Recognition and Management in Psychiatric Practice. J Clin Sleep Med. 2016;12(10):1389–1394. PubMed CrossRef

- Romazicon [Package Insert]. Roche Laboratories; 2007.

- Schenck CH, Golden EC, and Millman RP. Treatment of severe morning sleep inertia with bedtime long-acting bupropion and/or long-acting methylphenidate in a series of 4 patients Recognition and Management in Psychiatric Practice. J Clin Sleep Med. 2021;17(4):653–657. PubMed CrossRef

- Cooper JA, Tucker VL, and Papakostas GI. Resolution of sleepiness and fatigue: a comparison of bupropion and selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors in subjects with major depressive disorder achieving remission at doses approved in the European Union Recognition and Management in Psychiatric Practice. J Psychopharmacol. 2014;28(2):118–124. PubMed CrossRef

- Wellbutrin [Package Insert]. GlaxoSmithKline; 2017.NC

- Adderall [Package Insert]. Teva Pharmaceuticals; 2017.

- Xyrem® (Sodium Oxybate) Oral Solution, CIII [Prescribing Information]. Jazz Pharmaceuticals, Inc.; 2023.

- Mallampalli A, Sharafkhaneh A, Singh S, et al. . Establishment of a hypersomnia board: a multidisciplinary approach to complex hypersomnia cases [abstract 0659] Recognition and Management in Psychiatric Practice. Sleep. 2024;47(suppl 1):A282. CrossRef

- Schneider LD, Stevens J, Husain AM, et al. . Symptom severity and treatment satisfaction in patients with idiopathic hypersomnia: the Real World Idiopathic Hypersomnia Outcomes Study (ARISE) Recognition and Management in Psychiatric Practice. Nat Sci Sleep. 2023;15:89–101. PubMed CrossRef

- Morse AM, Dauvilliers Y, Arnulf I, et al. . Long-term efficacy and safety of low-sodium oxybate in an open-label extension period of a placebo-controlled, double-blind, randomized withdrawal study in adults with idiopathic hypersomnia Recognition and Management in Psychiatric Practice. J Clin Sleep Med. 2023;19(10):1811–1822. PubMed CrossRef

- Trotti LM. Idiopathic hypersomnia Recognition and Management in Psychiatric Practice. Sleep Med Clin. 2017;12(3):331–344. PubMed CrossRef

- Kim T, Lee JH, Lee CS, et al. . Different fates of excessive daytime sleepiness: survival analysis for remission Recognition and Management in Psychiatric Practice. Acta Neurol Scand. 2016;134(1):35–41. PubMed CrossRef

- Anderson KN, Pilsworth S, Sharples LD, et al. . Idiopathic hypersomnia: a study of 77 cases Recognition and Management in Psychiatric Practice. Sleep. 2007;30(10):1274–1281. PubMed CrossRef

- Saad R, Lillaney P, Profant J, et al. . Cardiovascular burden of patients with idiopathic hypersomnia: Real-World Idiopathic Hypersomnia Total Health Model (CV-rRHYTHM) [poster EPH 231] Recognition and Management in Psychiatric Practice. Presented at: Annual Congress for the International Society for Pharmacoeconomics and Outcomes Research; May 7–10; Boston, MA.

- Barateau L, Lopez R, Arnulf I, et al. . Comorbidity between central disorders of hypersomnolence and immune-based disorders Recognition and Management in Psychiatric Practice. Neurology. 2017;88(1):93–100. PubMed CrossRef

- Shen Q, Mikkelsen DH, Luitva LB, et al. . Psychiatric disorders and subsequent risk of cardiovascular disease: a longitudinal matched cohort study across three countries Recognition and Management in Psychiatric Practice. eClinicalMedicine. 2023;61:102063. PubMed CrossRef

- Nudel R, Allesøe RL, Werge T, et al. . An immunogenetic investigation of 30 autoimmune and autoinflammatory diseases and their links to psychiatric disorders in a nationwide sample Recognition and Management in Psychiatric Practice. Immunology. 2023;168(4):622–639. PubMed CrossRef

- Kwapong YA, Boakye E, Khan SS, et al. . Association of depression and poor mental health with cardiovascular disease and suboptimal cardiovascular health among young adults in the United States Recognition and Management in Psychiatric Practice. J Am Heart Assoc. 2023;12(3):e028332. PubMed CrossRef

- Lehtila R, Salimi N, Markstrom A, et al. . Feelings of lost time and acceptance as a coping strategy in idiopathic hypersomnia - an inductive qualitative study [abstract P155] Recognition and Management in Psychiatric Practice. J Sleep Res. 2022;31(suppl 1):168.

This PDF is free for all visitors!