Abstract

Pregabalin is a gabapentinoid. It does not act on GABA receptors; rather, it inhibits calcium influx into neurons by acting on the α2δ-1 subunit of voltage-gated calcium channels. This reduces release of excitatory neurotransmitters, thereby, perhaps, explaining the sedative, anxiolytic, anticonvulsant, and other properties of the drug. Pregabalin has been approved for neuropathic pain, fibromyalgia, partial-onset seizures, and generalized anxiety disorder, and is used, off-label, for pain in many other contexts and for alcohol use disorder, pruritus, restless legs syndrome, and sleep disorders. It may also be abused. About 0.04%–0.14% of women may use pregabalin during pregnancy. This article examines outcomes of pregnancies that were exposed to pregabalin. A meta-analysis of 7 cohort studies found that, even in unadjusted analysis, pregabalin was not associated with an increased risk of major congenital malformations. This finding was confirmed in later studies; or, if the unadjusted risk was significantly elevated, it was no longer so in adjusted analysis. Many studies found that anytime gestational exposure to pregabalin was not associated with a significantly elevated risk of other important birth outcomes such as stillbirth, low birth weight, preterm birth, small for gestational age, low Apgar score, and microcephaly; or the risks were elevated before but not after adjustment for covariates and confounds; or the risks were not significant relative to disease controls. Similarly, studies found that anytime gestational exposure to pregabalin was associated with no increase in risk, or with a significantly increased risk of attention-deficit/ hyperactivity disorder and related disorders, autism spectrum disorder and related disorders, and intellectual disability before but not after adjustment for covariates and confounds. As a limitation, pregabalin-exposed pregnancy sample sizes were small in all studies. On the positive side, safety impressions were obtained despite negligible adjustment for genetic, illness behavior, and environmental confounds.

J Clin Psychiatry 2026;87(1):25f16279

Author affiliations are listed at the end of this article.

Gabapentin was synthesized in the mid-1970s, when GABAergic mechanisms were being explored for the treatment of neurological disorders. Gabapentin was discovered to have anticonvulsant properties. A limitation of gabapentin, however, was that its absorption was slow (Tmax, 3–4 h); another limitation was that as the dose increased, the proportion of drug absorbed decreased. This led to the search for similar but better drugs, and pregabalin was the result.1–3

Pregabalin is a gabapentinoid; that is, it resembles gabapentin in its mechanism of action. Neither gabapentin nor pregabalin acts on GABA receptors. Rather, both act on the α2δ-1 subunit of voltage-gated calcium channels, with pregabalin showing higher affinity for binding than gabapentin. Through this action, these drugs inhibit influx of calcium into neurons and the subsequent release of excitatory neurotransmitters.2,3 Simplistically, such dampening of excitatory neurotransmission may explain the sedative, anxiolytic, anticonvulsant, and other properties of the drugs.

Pregabalin is more rapidly absorbed than gabapentin (Tmax, 1 h) and, unlike gabapentin, its absorption is proportionate to the dose administered (bioavailability, >90%). Pregabalin is negligibly bound to plasma proteins, undergoes negligible hepatic metabolism, does not induce or inhibit CYP enzymes, and is almost completely renally excreted in the unchanged form with a half-life of 5–7 h.1–3

Pregabalin has been approved for neuropathic pain, fibromyalgia, partial-onset seizures, and generalized anxiety disorder in different parts of the world. It may be used, off-label, for pain in a variety of other contexts and for alcohol use disorder, pruritus, restless legs syndrome, and sleep disorders.4–6 It may also be abused.7

Prevalence of Use of Pregabalin in Pregnancy

Women receiving pregabalin for an approved or off-label indication, and those abusing the drug, may choose to become pregnant or may inadvertently become pregnant while on the drug. In this context, a study in the US reported that, during 2000–2010, 477 (0.04%) out of 1,323,432 pregnancies with a live birth had been exposed to pregabalin during the first trimester.8 This figure, for pregnancies ending in live births or stillbirths, was 0.09% in Denmark, Finland, Norway, and Sweden during 2005–2016.9 A French study that examined data in a mother-child register found that, during 2013–2021, 12,534 (0.14%) out of 8,669,502 pregnancies had been exposed to pregabalin; time trends showed an increasing rate of exposure.10

As percentages, these numbers are small. However, the absolute numbers indicate that meaningful numbers of pregnant women in different countries are exposed to pregabalin, and the numbers are increasing.10 It is therefore necessary to understand what the risks associated with gestational exposure may be. The present article updates an earlier article in this column.11 Most of the new information available is on major congenital malformations (MCMs), some information is on neurodevelopmental disorders (NDDs), and some information on other pregnancy outcomes.

Pregabalin and Major Congenital Malformations: Meta-Analysis

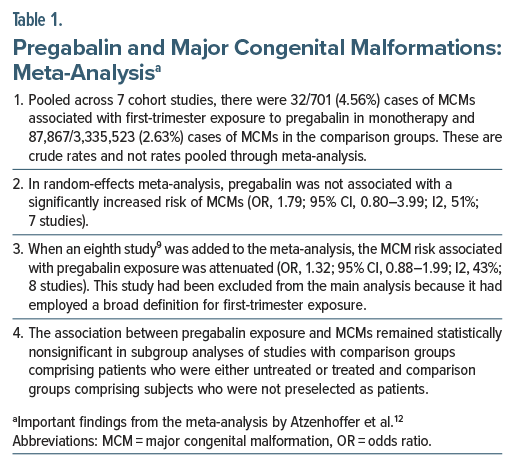

Atzenhoffer et al12 described a systematic review and meta-analysis of MCMs associated with first-trimester exposure to pregabalin in monotherapy. These authors identified 7 cohort studies, published between 2013 and 2024, that spanned data collection periods between 1996 and 2022. Four of the studies were prospective and 3 were retrospective. The studies drew information from about 50 countries, with Europe and North America contributing the most data. Comparison groups for 6 studies comprised unexposed subjects; in the seventh study, subjects were patients exposed to other medications. The comparison groups were disorder-free in 1 study, disorder-positive in 3 studies, and from the general population in 3 studies. Only 1 study presented adjusted analyses.

The exposed sample size ranged from 1 to 471, and the unexposed sample size, from 176 to 1,750,259. The total exposed sample was 701, and the total unexposed sample was 3,335,523. Important findings from the meta-analysis are presented in Table 1. In summary, despite the pooled estimate being dominated by studies that presented unadjusted analyses, first trimester exposure to pregabalin in monotherapy was not associated with a significantly increased risk of MCMs in offspring. This conclusion was consistent in both main and additional analyses.

An interesting observation is that the only study8 that presented an adjusted analysis (exposed n=471; unexposed n=1,750,259) obtained an odds ratio (OR) that was close to null (OR, 0.99; 95% confidence interval [CI], 0.66–1.47).

An important limitation of this meta-analysis12 is that, although it pooled data from 7 cohort studies, the total number of exposed pregnancies was just 701, and there were only 32 MCM events among these pregnancies. As an additional limitation, the meta-analysis team did not appear to have examined the possibility of overlap of data across the 7 studies. A limitation that was out of the control of the meta-analysis team is that, in 6 of the 7 studies, the source data comprised unadjusted analyses.

Pregabalin and Major Congenital Malformations: The Nordic Study

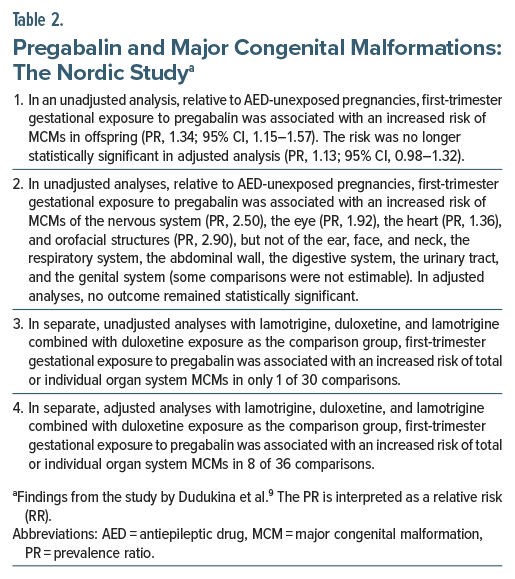

In a retrospective cohort study, Dudukina et al9 extracted data on 3,118,680 livebirths and stillbirths from population-based registers in Denmark, Finland, Norway, and Sweden for the years 2005–2016. Data were available for 2,332 pregnancies that had been exposed to pregabalin. Important findings from the study are presented in Table 2. In summary, first-trimester gestational exposure to pregabalin was associated with an increased risk of any malformation in crude but not in adjusted analyses; whereas scattered statistical significances were found in individual organ system analyses, these were very few and could well have been type 1 (false positive) statistical errors arising from the large number of statistical tests performed. Other limitations were that first-trimester was defined as a window of 90 days before to 97 days after the last menstrual period (so, women who stopped medication before conception would have been misclassified as exposed, potentially lowering the estimate of risk) and that many analyses were based on few MCM events and may therefore have been unreliable.

Pregabalin and Major Congenital Malformations: Other Recent Studies

A Turkish multicenter retrospective case-control study with data from 2013 to 2022 found a nonsignificantly increased crude risk of MCMs in (mostly) first-trimester, pregabalin-exposed pregnancies (11.1% vs 4.5%; odds ratio [OR], 2.63; 95% CI, 0.55–12.54).13 The sample in this study was small, comprising only 27 pregnancies exposed to pregabalin and 88 unexposed pregnancies.

In a study of data extracted from the North American Antiepileptic Drug Pregnancy Registry for the period 1997–2023, Hernandez-Diaz et al14 reported 2 (3.2%) MCMs in 62 pregnancies with first-trimester exposure to pregabalin monotherapy. The unadjusted risk was not significantly elevated relative to lamotrigine exposure (relative risk [RR], 1.53; 95% CI, 0.38–6.13). The unadjusted RR was 2.82 (95% CI, 0.66–12.06) relative to unexposed controls; this, again, was not statistically significant.

Pregabalin and Other Birth Outcomes

In a Swedish study15 for the years 1996–2013, there was no significant difference between pregabalin and lamotrigine for gestation duration, birth weight, and head circumference. Part of the data in this study is likely to have overlapped with the data from the Nordic study by Dudukina et al.9

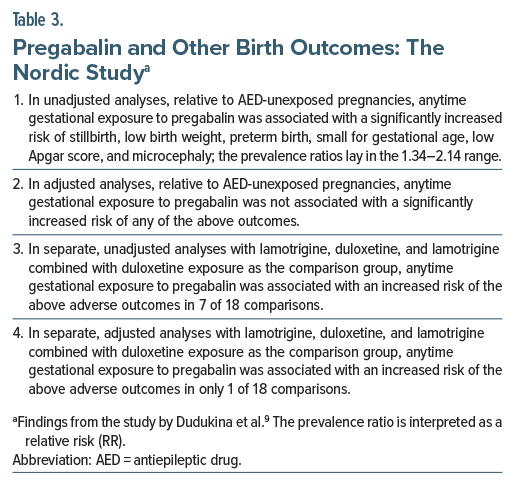

The previously described Nordic cohort study by Dudukina et al9 reported on many birth outcomes. Important findings are presented in Table 3. In summary, anytime gestational exposure to pregabalin was associated with a significantly increased risk of stillbirth, low birth weight, preterm birth, small for gestational age, low Apgar score, and microcephaly before but not after adjustment for covariates and confounds.

The small Turkish study13 referred to in an earlier section found that, relative to unexposed pregnancies, gestational exposure to pregabalin was associated with a significantly increased risk of low birth weight (22.2% vs 6.2%; OR 4.34; 95% CI, 1.21–15.64), a near-significantly increased risk of preterm delivery (18.5% vs 5.7%; OR, 3.73; 95% CI, 0.99–14.04), and a nonsignificantly increased risk of spontaneous abortion (6.5% vs 4.3%; OR, 1.53; 95% CI, 0.27–8.82). The ORs and 95% CIs presented here and in the earlier section on MCMs are all crude (unadjusted) values and were computed from information presented in the paper.

In a population-based retrospective cohort study, Christensen et al16 examined fetal growth outcomes in liveborn singleton children in Denmark, Finland, Iceland, Norway, and Sweden for the years 1996–2017. In adjusted analyses, they found that, relative to pregnancies unexposed to antiepileptic drugs (AEDs), gestational exposure to pregabalin in monotherapy was associated with an increased risk of being born small for gestational age (OR, 1.16; 95% CI, 1.02–1.31) and an increased risk of low birth weight (OR, 1.23; 95% CI, 1.03–1.47). However, neither outcome was statistically significant when the comparison group comprised disease controls, that is, women with epilepsy who were unexposed to AEDs (OR, 1.01; 95% CI, 0.58–1.77 and OR, 0.92; 95% CI, 0.44–1.92, respectively).

Pregabalin and Neurodevelopmental Disorders

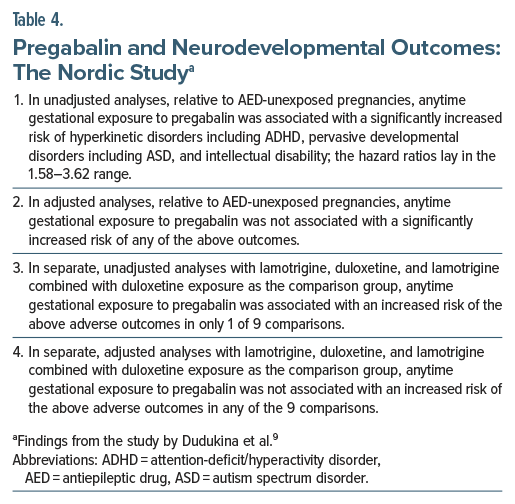

The previously described Nordic cohort study by Dudukina et al9 reported neurodevelopmental outcomes in offspring who were followed for 1 to up to 12 years. Important findings are presented in Table 4. In summary, anytime gestational exposure to pregabalin was associated with a significantly increased risk of attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) and related disorders, autism spectrum disorder (ASD) and related disorders, and intellectual disability (ID) before but not after adjustment for covariates and confounds.

A nationwide, population-based, retrospective French cohort study17 with data extracted from national healthcare databases for the years 2011–2014 found no increase in the risk of mental and behavioral disorders in general, pervasive developmental disorders and mental retardation in particular, and visits to speech therapists in 1,627 children who had had prenatal exposure to pregabalin. Another nationwide, population-based, retrospective French cohort study,18 probably a superset of the previous study, reporting data for 2011–2016, found a borderline increase in the risk of mental and behavioral disorders in general (hazard ratio, 1.5; 95% CI, 1.0–2.1) but no increase in the risk of pervasive developmental disorders, mental retardation, disorders of psychological development, and disorders of childhood and adolescence. These analyses were based on 1,627 children who had been prenatally exposed to pregabalin relative to 1,710,441 unexposed children.

A Nordic study19 with data from Denmark, Finland, Iceland, Norway, and Sweden for the years 1996–2017 found no association between prenatal exposure to pregabalin and either ASD or ID. The data from this study probably overlapped much with the data from Dudukina et al.9

Summary

In different studies and in unadjusted analyses, gestational exposure to pregabalin was associated with no increase in risk or with a significantly increased risk of MCMs, stillbirth, low birth weight, preterm birth, small for gestational age, low Apgar score, microcephaly, ADHD, ASD, and ID. In adjusted analyses, or in analyses with disease control comparisons, in almost all studies, almost all findings were no longer statistically significant.

Given that genetic risk factors, maternal illness–related risk factors, and family environmental risk factors are mostly unknown, unmeasured, or inadequately measured and adjusted for, residual confounding could well explain statistical significance, where still present in adjusted analyses. This does not negate the possibility of a true effect for pregabalin; however, if pregabalin does, indeed, have a true effect in increasing the risk of any of these adverse outcomes, the increase in risk is likely to be small. This is a nuanced conclusion because we do not as yet have reliable information on risks based on dose and duration of exposure.

These considerations should be discussed with pregnant women who may be using pregabalin, and a shared decision should be made and documented on a case-by-case basis.

Parting Note

The studies available to date convey the general impression that pregabalin may or may not be associated with an increased risk of different pregnancy outcomes and that these risks are not statistically significant in analyses that adjust for covariates and confounds. This impression must be tempered by the recognition that pregabalin exposure during pregnancy is uncommon, and that pregabalin-exposed sample sizes were consequently small in all studies, including in the meta-analysis discussed in this article. On the positive side, the impressions of safety were obtained despite minimal adjustment for confounding in the available studies, and despite the unavailability of pre-pregnancy exposure analysis, paternal exposure analysis, discordant sibling pair analysis, and similar research designs that indirectly address confounding by genetic, illness-related, and environmental risk factors.

Article Information

Published Online: January 7, 2026. https://doi.org/10.4088/JCP.25f16279

© 2026 Physicians Postgraduate Press, Inc.

To Cite: Andrade C. Pregabalin in pregnancy: major congenital malformations, other birth outcomes, and neurodevelopmental outcomes. J Clin Psychiatry. 2026;87(1):25f16279.

Author Affiliations: Department of Clinical Psychopharmacology and Neurotoxicology, National Institute of Mental Health and Neurosciences, Bangalore, India; Department of Psychiatry, Kasturba Medical College, Manipal Academy of Higher Education, Manipal, India.

Corresponding Author: Chittaranjan Andrade, MD, Department of Clinical Psychopharmacology and Neurotoxicology, National Institute of Mental Health and Neurosciences, Bangalore 560029, India ([email protected]).

Relevant Financial Relationships: None.

Funding/Support: None.

Each month in his online column, Dr Andrade considers theoretical and practical ideas in clinical psychopharmacology with a view to update the knowledge and skills of medical practitioners who treat patients with psychiatric conditions.

Each month in his online column, Dr Andrade considers theoretical and practical ideas in clinical psychopharmacology with a view to update the knowledge and skills of medical practitioners who treat patients with psychiatric conditions.

Department of Clinical Psychopharmacology and Neurotoxicology, National Institute of Mental Health and Neurosciences, Bangalore, India. Please contact Chittaranjan Andrade, MD, at Psychiatrist.com/contact/andrade.

References (19)

- Sills GJ. The mechanisms of action of gabapentin and pregabalin. Curr Opin Pharmacol. 2006;6(1):108–113. PubMed CrossRef

- Bockbrader HN, Wesche D, Miller R, et al. A comparison of the pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics of pregabalin and Gabapentin. Clin Pharmacokinet. 2010;49(10):661–669. PubMed CrossRef

- Chincholkar M. Gabapentinoids: pharmacokinetics, pharmacodynamics and considerations for clinical practice. Br J Pain. 2020;14(2):104–114. PubMed CrossRef

- Sancar F. Textured breast implant recall. JAMA. 2019;322(11):1036. PubMed CrossRef

- de Ternay J, Meley C, Guerin P, et al. National impact of a constraining regulatory framework on pregabalin dispensations in France, 2020-2022. Int J Drug Pol. 2025;135:104660. PubMed CrossRef

- Athavale A, Murnion B. Gabapentinoids: a therapeutic review. Aust Prescr. 2023;46(4):80–85. PubMed CrossRef

- Goins A, Patel K, Alles SRA. The gabapentinoid drugs and their abuse potential. Pharmacol Ther. 2021;227:107926. PubMed CrossRef

- Patorno E, Bateman BT, Huybrechts KF, et al. Pregabalin use early in pregnancy and the risk of major congenital malformations. Neurology. 2017;88(21):2020–2025. PubMed CrossRef

- Dudukina E, Szépligeti SK, Karlsson P, et al. Prenatal exposure to pregabalin, birth outcomes and neurodevelopment - a population-based cohort study in four Nordic countries. Drug Saf. 2023;46(7):661–675. PubMed CrossRef

- Shahriari P, Drouin J, Miranda S, et al. Trends in prenatal exposure to antiseizure medications over the past decade: a nationwide study. Neurology. 2025;105(4):e213933. PubMed CrossRef

- Andrade C. Safety of pregabalin in pregnancy. J Clin Psychiatry. 2018;79(5):18f12568. PubMed CrossRef

- Atzenhoffer M, Peron A, Picot C, et al. The use of pregabalin in early pregnancy and major congenital malformations: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Reprod Toxicol. 2025;136:108958. PubMed CrossRef

- Kaskal M, Kuru B, Erkoseoglu I, et al. Evaluation of the teratogenic effects of pregabalin usage during pregnancy: a multicenter case-control study. North Clin Istanb. 2024;11(5):460–465. PubMed CrossRef

- Hernandez-Diaz S, Quinn M, Conant S, et al. Use of antiseizure medications early in pregnancy and the risk of major malformations in the newborn. Neurology. 2025;105(3):e213786. PubMed CrossRef

- Margulis AV, Hernandez-Diaz S, McElrath T, et al. Relation of in-utero exposure to antiepileptic drugs to pregnancy duration and size at birth. PLoS One. 2019;14(8):e0214180. PubMed CrossRef

- Christensen J, Zoega H, Leinonen MK, et al. Prenatal exposure to antiseizure medications and fetal growth: a population-based cohort study from the Nordic countries. Lancet Reg Health Eur. 2024;38:100849. PubMed CrossRef

- Blotière PO, Miranda S, Weill A, et al. Risk of early neurodevelopmental outcomes associated with prenatal exposure to the antiepileptic drugs most commonly used during pregnancy: a French nationwide population-based cohort study. BMJ Open. 2020;10(6):e034829. PubMed

- Coste J, Blotiere PO, Miranda S, et al. Risk of early neurodevelopmental disorders associated with in utero exposure to valproate and other antiepileptic drugs: a nationwide cohort study in France. Sci Rep. 2020;10(1):17362. PubMed CrossRef

- Bjørk MH, Zoega H, Leinonen MK, et al. Association of prenatal exposure to antiseizure medication with risk of autism and intellectual disability. JAMA Neurol. 2022;79(7):672–681. PubMed

This PDF is free for all visitors!