New research out of Pitt represents the latest salvo in the never-ending nature vs. nurture debate. A team of researchers have just published a paper that argues that the way an infant’s brain is wired at just three months old could help predict how he (or she) will handle emotions later on in life. This discovery could offer up some early insight into looming mental health challenges.

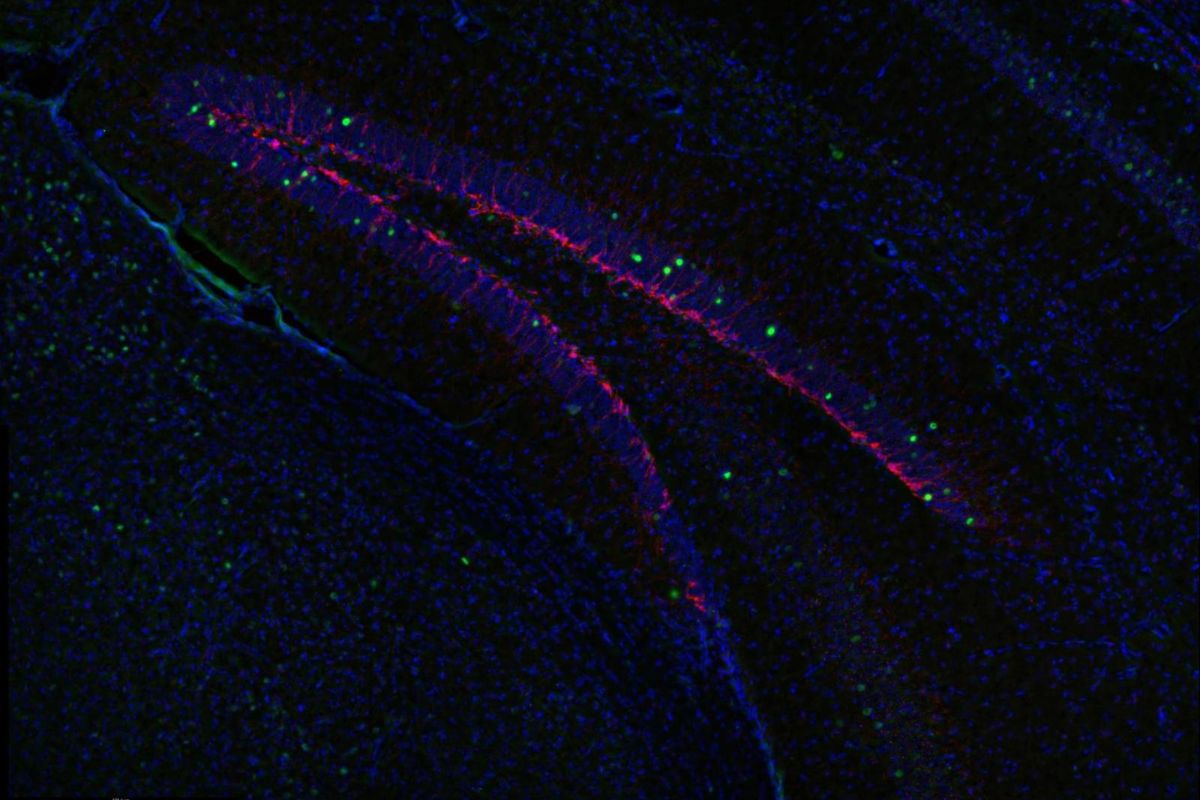

The members of the multi-institutional team took a closer look at the brain structure of infants using Neurite Orientation Dispersion and Density Imaging (NODDI). This allowed the team to learn how emotional traits – such as negative emotionality (NE), positive emotionality (PE), and soothability – evolve early on. Specifically, they turned their attention to key white matter (WM) tracts in the brain, which link the regions responsible for emotional processing and regulation.

“What we’re seeing is that the brain’s structural organization in early infancy sets the stage for emotional development,” the researchers wrote.

Methodology

The team studied the brains of 95 infants at three months old, tracking how brain microstructure related to shifts in temperament for six months. The researchers then looked at a separate test group of 44 infants to replicate the findings.

The researchers focused on several major WM tracts:

- The forceps minor (FM), which ties prefrontal brain regions across hemispheres.

- The cingulum bundle (CB), which links areas involved in attention and emotion regulation.

- And the uncinate fasciculus (UF), which connects the temporal lobe and frontal brain regions.

Our Emotions Are Wired Early

The study’s authors found that infants with higher neurite dispersion — a sign of more complex or less pruned neural wiring — in the FM at three months showed a notable jump in negative emotionality by nine months. This, they suggest, might indicate greater integration among brain networks responsible for internal processing and emotional salience. As a result, they argue that this could potentially overload young cognitive systems that aren’t ready yet to regulate strong feelings.

On the other hand, infants with higher neurite density and dispersion in the left CB at three months appeared to develop more positive emotionality and better soothability over time. This bundle connects areas of the brain that support executive function, which hints at stronger early connectivity in these regions that could help infants manage and respond more productively to environmental changes.

“Understanding these early neural markers could transform how we approach infant mental health, allowing for targeted interventions during critical developmental windows,” one of the study’s lead authors Mary Phillips, MD, added.

Phillips is the Pittsburgh Foundation-Emmerling Endowed Chair in Psychotic Disorders and distinguished professor of psychiatry, bioengineering, and clinical and translational science at Pitt’s school of medicine.

Identifying – and Understanding – the Warning Signs

What these researchers uncovered is critical because of the established connection between early emotional traits and later mental health outcomes. For example, earlier studies have already revealed a link between high negative emotionality and an elevated risk of mood and behavioral disorders later in life.

Conversely, researchers have tied low positive emotionality and poor soothability to disorders such as anxiety and depression – in addition to other social challenges.

Until now, most of the published research on infant emotional development has been the product (almost exclusively) of simple behavioral observations. But this new study integrates behavioral data with high-resolution brain imaging. Consequently, it paints a much clearer picture of the neural mechanisms at work. It also could offer earlier identification of at-risk kids.

The researchers point out that while NODDI provides a more detailed glimpse of the brain’s microstructure than traditional imaging methods, they also validated their findings using conventional diffusion tensor imaging.

Nevertheless, the authors suggest a look into how the brain structure in specific subregions might change over time and how that could influence emotional development.

Ultimately, the research highlights the potential of using early brain scans to help figure out which babies might need extra support as they age. It could pave the way for earlier and more productive mental health interventions.

Further Reading

Nature vs. Nurture? Parenting Scores a Win

The Kids Aren’t All Right. Study Says They Need to Get Outside.