Cognitive-behavioral therapy (CBT) remains one of the most effective tools against major depressive disorder (MDD). But beyond reducing symptoms, can this approach to therapy change the brain’s structure?

A new study published in Translational Psychiatry says yes. The paper’s authors found that 20 sessions of CBT can boost gray matter volume in critical brain regions tied to emotion regulation.

Past imaging studies have repeatedly shown structural shrinkage in limbic areas such as the hippocampus and amygdala. And somatic treatments, such as antidepressants and electroconvulsive therapy (ECT), have also shown shifts in brain volume.

But psychotherapy’s impact on brain structure has remained largely uncharted territory. The late Nobel laureate Eric Kandel argued that lasting psychotherapy must, by definition, leave physical footprints in the brain. This study appears to have uncovered the trail.

“Cognitive behavioural therapy was already known to work. Now, for the first time, we have a reliable biomarker for the effect of psychotherapy on brain structure. Put simply, psychotherapy changes the brain,” corresponding author and University of Halle professor Ronny Redlich explained.

Methodology

Halle researchers – along with their University of Münster colleagues – recruited 30 adults diagnosed with MDD and 30 healthy controls. The team treated each patient with CBT in line with Germany’s national health guidelines, typically over a span of about 40 weeks. Licensed therapists or supervised trainees delivered the sessions.

Participants then underwent MRI scans before therapy began and again after wrapping up 20 sessions. At each point, participants also completed depression assessments – the Hamilton Depression Rating Scale and Beck Depression Inventory – as well as the Toronto Alexithymia Scale.

Clear Results

By the end of the treatment, patients showed a remarkable drop in depression scores. Nearly two-thirds of them moved from acute episodes into partial or full remission. But, perhaps most importantly, patients also reported improvement in their ability to identify and acknowledge their own emotions.

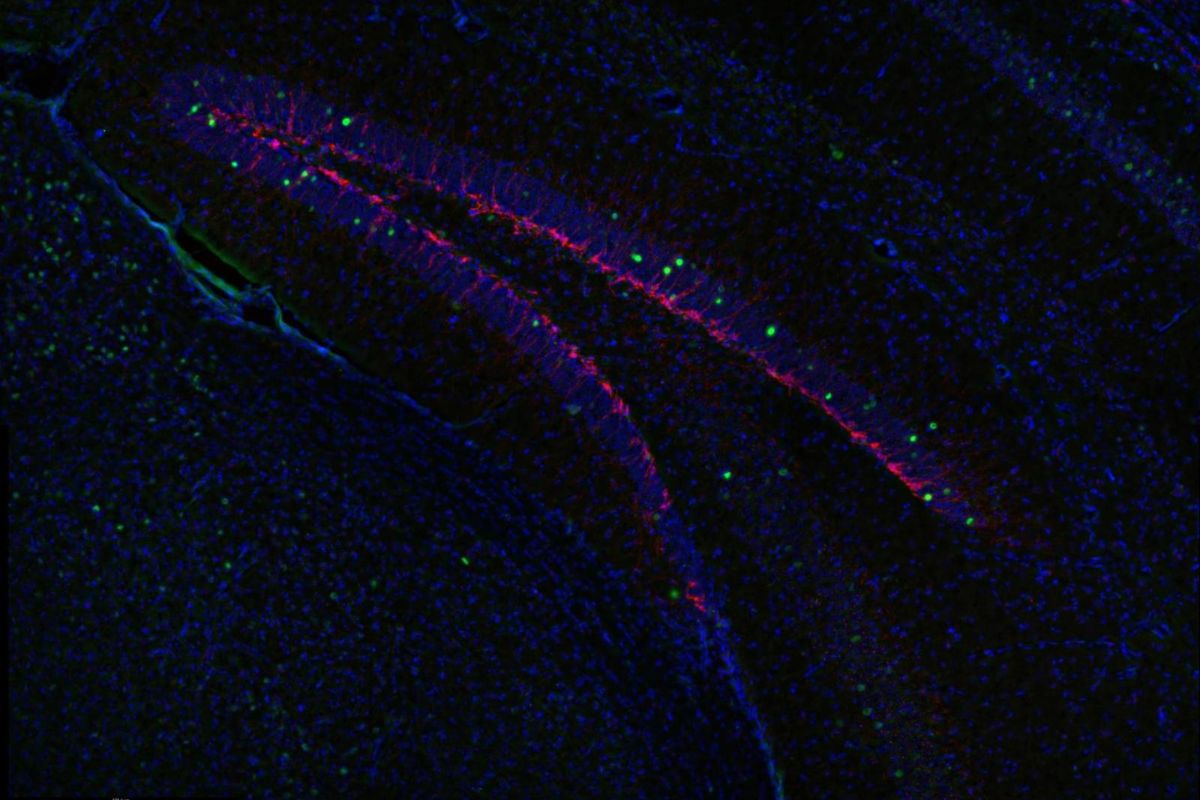

The MRI results backed up those assessments. The images exposed dramatic shifts in gray matter volume (GMV). Compared against the participants’ baseline scans, patients showed increases in the bilateral amygdala and the right anterior hippocampus. At the same time, the researchers noticed a drop in the right posterior hippocampus.

Healthy control group participants didn’t show these structural changes over the same timeframe. This, they posit, hints that the therapy itself – and not time – drove these changes.

But maybe the most compelling discovery seems to be the connection between brain growth and emotional awareness. Patients who showed the greatest increase in volume in the right amygdala also reported the most dramatic improvement in identifying their feelings.

On the other hand, the researchers failed to unearth a direct connection between brain changes and overall depression scores. This mismatch suggests that CBT’s effects on the brain might be a little more nuanced, and they target specific emotional skills instead of offering overall symptom relief.

Why It Matters

The results add to a growing body of literature that psychotherapy isn’t just “talk.” It’s neurobiological intervention.

But there’s more to it than that. Some studies have reported enlarged amygdalae in acute depression patients, leading to debate over whether “bigger” equals “better.” The authors point out that – in their patients – amygdala growth appeared to reflect healthier emotional processing. This, they add, suggests that volume increases could reflect adaptive remodeling.

The team’s focus on alexithymia proved insightful. Difficulty identifying emotions is common in depression but the standard diagnostic checklists typically overlook them. Yet reducing this impairment might be a critical moment in recovery.

The study supports earlier research that illustrates that as patients learn to name and work with their feelings, their symptoms and brain structure seem to change together..

Despite caveats, the findings suggest a compelling possibility: measurable brain changes as a biomarker for psychotherapy’s impact. If future research manages to replicate this study, such markers could help personalize treatment.

For now, the takeaway is clear. CBT doesn’t just help patients think and feel differently. It reshapes the brain regions that govern those processes. That makes therapy not just a conversation, but a form of brain change – plasticity harnessed for healing.

Further Reading

Therapist-Guided Versus Self-Guided Cognitive-Behavioral Therapy