Doctors, nurses and med students know all too well that “tired but wired” feeling that comes after a long, sleepless night of studying or caring for patients. Now new research reveals something unexpected – pulling an all-nighter may actually help alleviate depression.

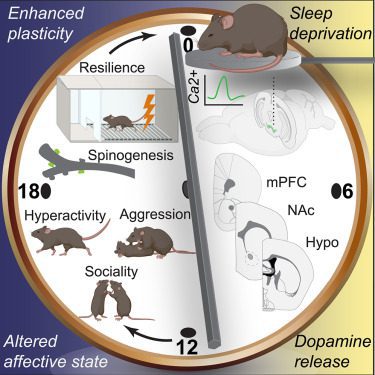

The study, published in the journal Neuron, involved inducing acute sleeplessness in mice and observing subsequent changes in their behavior and brain function. The findings suggest that short-term sleep loss could trigger significant alterations in the brain’s reward system, particularly through the increase of dopamine release, a neurotransmitter associated with pleasure and motivation.

Pimavanserin 34 mg at Bedtime for the Treatment of Insomnia in PTSD

Study Illuminates the Dark Side of Light Overexposure

Lemborexant and Daridorexant for the Treatment of Insomnia

Of Mice and Mood

The novel experimental setup subjected mice that did not have a genetic predisposition to psychological disorders to mild sleep deprivation. Researchers kept the mice awake just long enough to make them uncomfortable, but not so long they were completely stressed out. Basically, a scenario analogous to a human all-nighter.

Post-deprivation, the mice exhibited behaviors akin to a state of mania: increased aggression, hyperactivity, and hypersexuality. These behaviors were in stark contrast to those of the control group, which had been allowed to slumber peacefully.

Using advanced optical and genetic tools, the team was able to trace an increase in dopamine activity back to specific brain regions during the sleep deficit period. Notably, they identified the medial prefrontal cortex as a critical area for the observed antidepressant effects. Silencing dopamine activity in this region halted the antidepressant effect, underscoring its potential as a target for therapeutic interventions.

The study also examined synaptic plasticity; that is, the ability of the connections between neurons to dial their strength up or down in response to neural activity. Following the period of limited sleep, mice brains showed a propensity for forming new neural connections as evidenced by an increase in dendritic spines in the prefrontal cortex. This indicates that the brain rewires itself to maintain an elevated mood. However, when the researchers disrupted these newly formed synapses, once again, the antidepressant effects were reversed.

“Chronic sleep loss is well studied, and its uniformly detrimental effects are widely documented,” Northwestern University’s Yevgenia Kozorovitskiy, the lead author of the study said. “But brief sleep loss — like the equivalent of a student pulling an all-nighter before an exam — is less understood.”

Balancing the Sleep Ledger

The study’s surprising results don’t suggest that insufficient sleep is always a joyride. Scores of studies provide evidence to the contrary. One such study published recently in the Journal of Affective Disorders found that those who slept fewer than seven hours a night on average had an 86 percent greater chance of developing depression. (And to be fair, those who lingered in bed too long also experienced higher rates of mental distress.)

That said, the idea of occasionally burning the midnight oil to boost mood does have some scientific weight behind it. For example, a 2022 PNAS study with human subjects found that one night of sleep deprivation induced a rapid and effective psychological improvement in a subset of patients with depressive disorder. The so-called “wake therapy” appeared to enhance connectivity between the amygdala and the anterior cingulate cortex of the brain. Both of these regions play a role in emotional regulation.

Contrary study results could simply mean that most studies look at sleep patterns over time versus a single night. In general, sleep experts recommend 7-8 hours of shuteye on average for optimal mental and physical health. Occasionally staying up until sunrise probably doesn’t have much of a long term effect one way or the other.

Kozorovitskiy herself cautioned against pulling all-nighters to lift the spirits.

“The antidepressant effect is transient, and we know the importance of a good night’s sleep,” she said. “I would say you are better off hitting the gym or going for a nice walk. This new knowledge is more important when it comes to matching a person with the right antidepressant.”