Abstract

Objective: To evaluate the effects of gender-affirming surgery (GAS) on quality of life and gender dysphoria (GD) among individuals in the United States.

Data Sources: A literature search was conducted using PubMed, Web of Science, APA PsycINFO, APA, CINAHL Combined, and LGBTQ+ Source from February 2017 to February 2023. Randomized controlled trials and case reports/case series that described GD, quality of life, and gender surgery in the context of the United States were included.

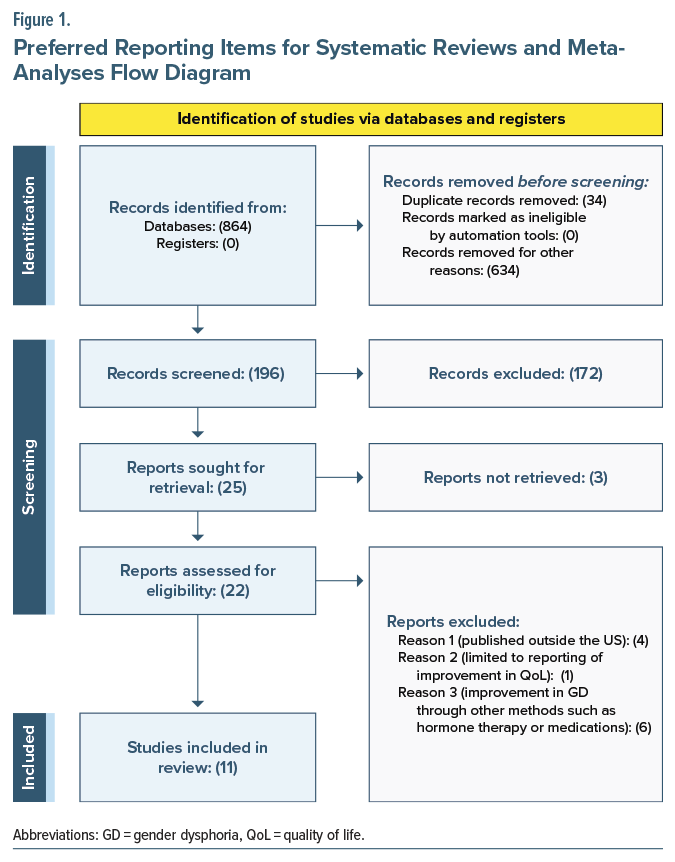

Study Selection: Five independent reviewers analyzed the studies; conducted screening of titles, abstracts, and full texts; resolved any disagreements through multiple rounds of review; and manually eliminated duplicate references. Reasons for exclusion were documented. The comprehensive search yielded 864 potentially relevant studies, of which 11 were included in the final analysis.

Data Extraction: For data analysis, the authors recorded information including mean age, gender assigned at birth, race, sample size, type of GAS, and measures/ questionnaires used to assess GD before and after surgery, concurrent therapies, history of mental health illnesses, and postoperative complications.

Results: The results showed that after the participants received combined procedures on the face, chest, or genitalia, there was a significant improvement in self-worth, social and psychological well-being, and sexual and physical appearance satisfaction, improving overall quality of life and GD.

Conclusions: Gender identity is a complex subject, and although the research is gaining momentum, much is yet to unfold. Despite the recent increase in access to gender assignment surgeries, there is a paucity of research to assess the quality of life and GD among these individuals after surgical interventions and among individuals who have accepted themselves.

Prim Care Companion CNS Disord 2025;27(6):23r03677

Author affiliations are listed at the end of this article.

Gender identity is one’s internal sense of self and gender, whether that is man, woman, or both. Most people identify as “male” or “female” (“binary” identities).1 Gender dysphoria (GD), previously known as gender identity disorder, refers to an intense discomfort or distress that results when a person’s assigned birth gender is not the same as the one with which they identify.1 GD can strongly impact a person’s quality of life, resulting from poor peer and family relations, depression and anxiety, substance use disorders, and poor self-esteem.1 According to the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fifth Edition, Text Revision (DSM-5-TR),2 GD prevalence accounts for 0.005%–0.014% of the population for biological males and 0.002%–0.003% for biological females. Several theories exist with regard to its etiology,1 which suggests that it is multifactorial and involves biological factors such as hormones and genetics and psychosocial factors such as severe childhood neglect, domestic violence, and physical and sexual abuse.3 Research shows areas of the brain that differ in transgender and nontransgender individuals, including the hippocampus and amygdala.3

Transgender people with GD are more likely to experience poor quality of life and mental health problems than the general population. Numerous studies have consistently shown higher rates of depression and anxiety, suicidal ideation, and substance use in the transgender population.4–6 However, these rates have consistently decreased following successful transition, with relief from GD being reported.7

In recent years, the number of transgender people seeking care has increased due to an increase in social acceptance and a decrease in stigmatization of GD. Gender-affirming care is an umbrella term that encompasses social, legal, and medical interventions to support transgender persons in their gender transition. This multidisciplinary approach to care is crucial for their overall health and well-being, improvement in psychological functioning, and decreased feelings of distress. Gender-affirming care and supported social transition have also been shown to correlate with reduced rates of depression, anxiety, and suicidal ideation.8,9

Hormone replacement therapy, psychotherapy, and gender-affirming surgery (GAS) are vital components in treating GD. Various surgical procedures are available to treat transgender people with GD.10 Genital surgery, or sex reassignment surgery, includes vulvoplasty, vaginoplasty, orchiectomy, facial feminization surgery in males, hysterectomy, vaginectomy, scrotoplasty, and mastectomy in females. GAS is being increasingly performed, and the results have been promising.11 It is becoming a vital component of health care in the United States, substantially improving the quality of life, satisfaction level, and long-term mental health among the transgender population experiencing GD.12–14

Although there is a recent increase in access to GAS, there is a lack of research to assess GD among transgender individuals after surgical interventions. To understand the impact of GAS on the GD of individuals, we aim to evaluate the effects of GAS on GD among individuals after surgery in the United States. We provide an overview of most surgeries done in all transgender populations with GD, their demographic factors, effects of GAS on other mental health disorders, quality-of-life improvement, and complications.

METHODS

We used 6 databases, including PubMed, Web of Science, APA PsycINFO, APA, CINAHL Combined, and LGBTQ+ Source databases, for our research. The literature search included English-language–only US studies published from February 2017 to February 2023. Search terms included a combination of relevant Medical Subject Heading terms such as “Gender Dysphoria OR Gender Identity Disorder OR Cisgender OR transgender OR transsexualism” AND “Gender Affirming Surgery OR Gender Reassignment Surgery OR Sex Reassignment Surgery OR Facial Reconstructive Surgery OR Chest Surgery OR Top Surgery OR Genital Surgery OR Bottom Surgery.”

For our inclusion criteria, GD was defined as a concept designated in the DSM-5-TR as clinically significant distress or impairment related to an ardent desire to be of another gender, which may include a desire to change primary and secondary sex characteristics. GAS was referred to as procedures that help people transition to their self-identified gender. Gender-affirming options may include facial surgery, top surgery, or bottom surgery. GAS gives transgender people a body that aligns with their gender. It may involve procedures on the face, chest, or genitalia. Original research, including randomized controlled trials, cohort studies, case-control studies, cross-sectional studies, case series, case reports, and qualitative studies, was evaluated in our study.

We included preprints and letters if they described original research that reported data on the outcomes of GAS on reducing GD. We excluded studies published outside of the United States and those limited to reporting improvement in quality of life only or reduction in GD through other methods of gender transformation such as hormone therapy or medical therapy. Duplicate references were removed manually. Five independent reviewers screened the titles, abstracts, and full texts of the articles. Any disagreement on including a title, abstract, or full-text article was retained for the next screening stage and reviewed multiple times by the reviewers (J.S.B., S.S., A.A., M.B.). Reasons for the exclusion of full texts were collected. This comprehensive search resulted in 864 potentially relevant studies, of which 11 studies were included for the final analysis (Figure 1).

For data analysis, we recorded the mean age, gender assigned at birth, race, sample size, GAS type, type of measures or questionnaires used for GD measurement before and after the surgery, concomitant therapies used before and/or after the surgery, history of any mental health illnesses, and postsurgery complications.

RESULTS

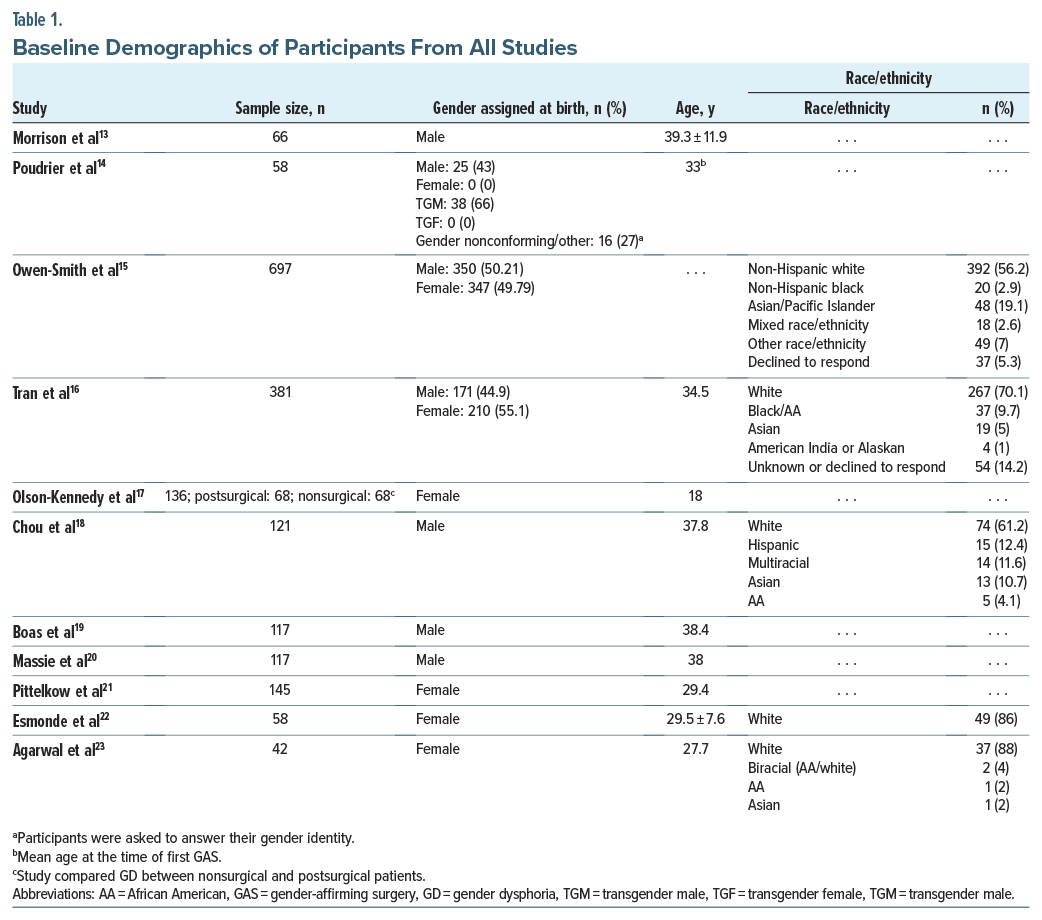

The mean sample size of participants in all studies was 182.1. The mean age of the participants was 34.7, while the mean age for males (gender assigned at birth) was 37.32 and for females (gender assigned at birth) was 30.27. Baseline demographics of the participants in all studies in our review included mean age, sample size, race/ethnicity, and gender distribution of all participants (Table 1).13–23 Tran et al16 noted that race was an independent predictor for complications for GAS.

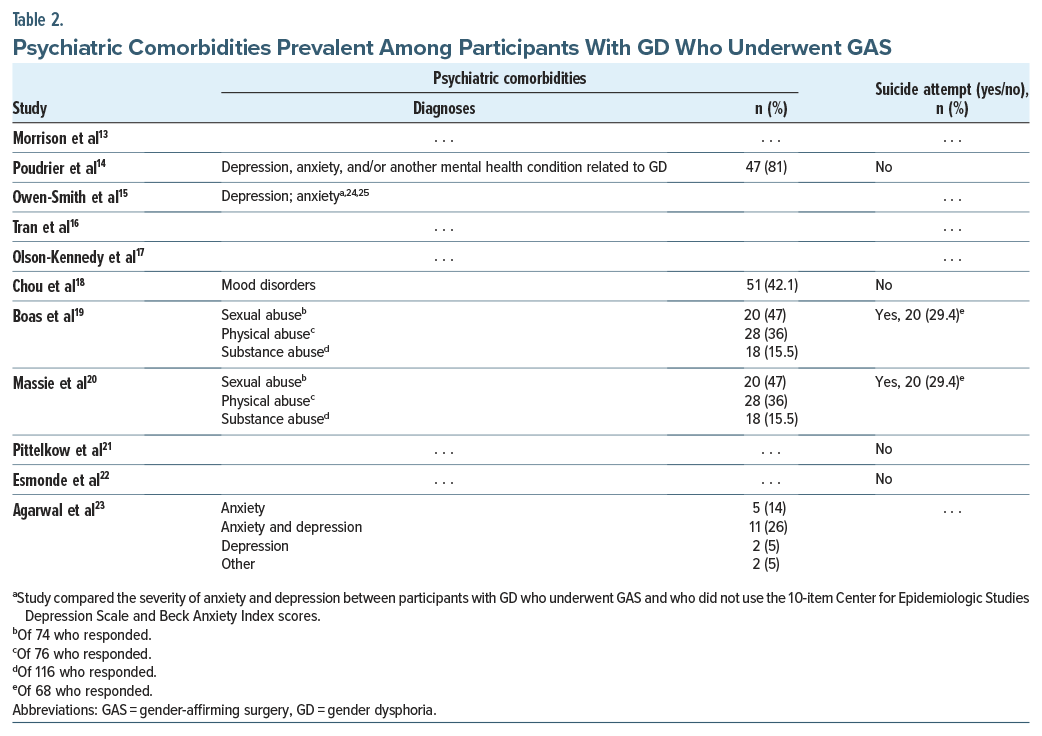

The most common psychiatric disorders among participants with GD who underwent GAS were mood disorders, substance abuse, depression, and anxiety.14,15,18,19,23 Owen-Smith et al15 studied the depression and anxiety severities using the 10-item Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression Scale24 and Beck Anxiety Index25 scores, respectively (Table 2).13–25

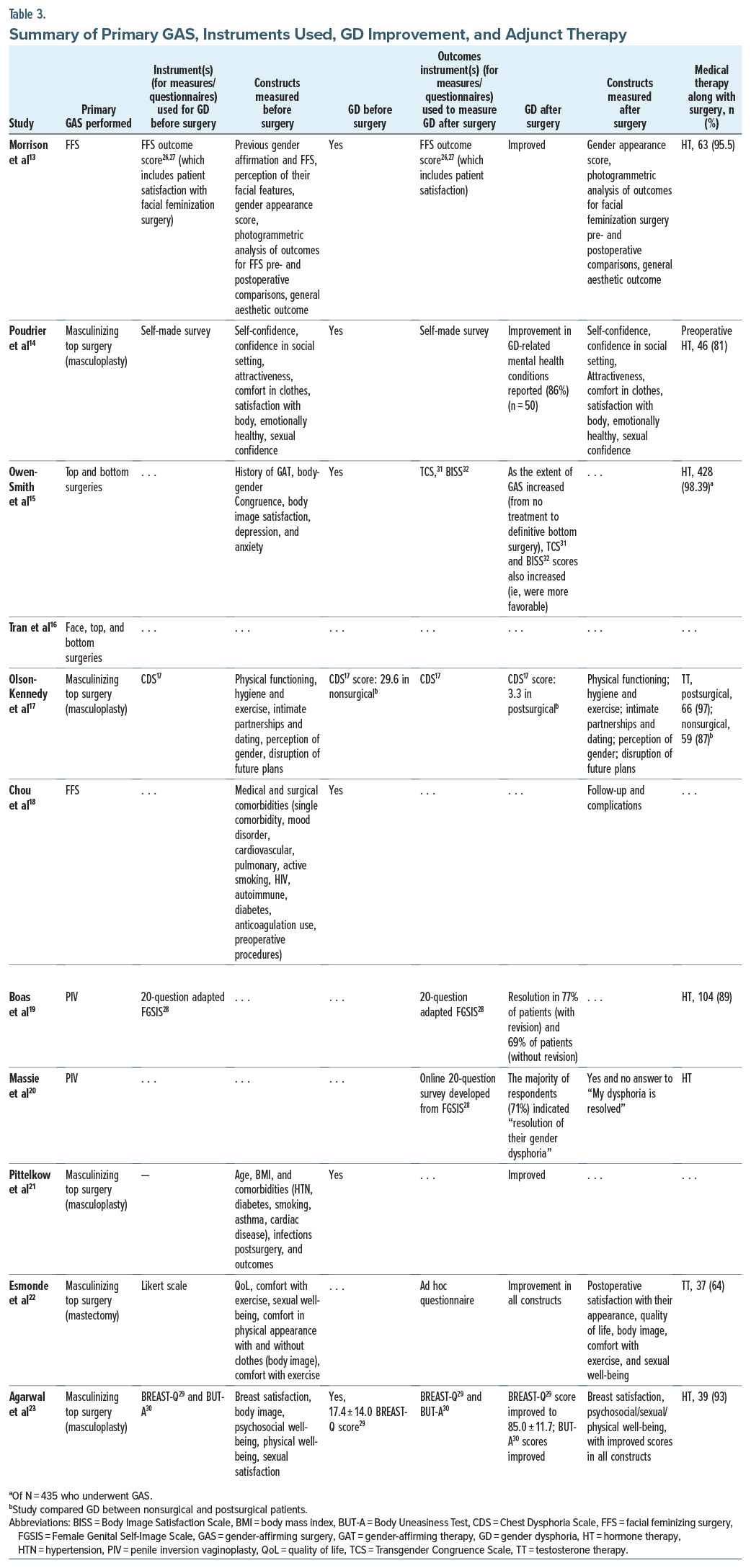

To evaluate GD among participants preoperatively and postoperatively, the studies used different questionnaires. One study13 used the Facial Feminizing Surgery (FFS) outcome score. This instrument was adapted from a tool validated in the general facial aesthetic surgery population to assess physical, emotional, and social domains of patient satisfaction with their face.26,27 It was then adapted for use in the transgender and gender-diverse population and underwent standard reliability validation and constitutes 9 questions scored on a 5-point Likert scale (ranging from 0 to 4, where 0 constitutes least satisfied, and 4 constitutes most satisfied).13

One study19 used the 20-question adapted Female Genital Self-Image Scale28 (FGSIS). Agarwal et al23 used the BREAST-Q29 and Body Uneasiness Test (BUT-A)30 and measured breast satisfaction and psychosocial/sexual/ physical well-being. Another study17 developed and utilized the Chest Dysphoria Scale (CDS) to analyze GD before surgery. The CDS measures physical functioning, hygiene and exercise, intimate partnerships and dating, perception of gender, and disruption of the future.17

A few measures that were used to assess GD postoperatively include the FFS outcome score26,27 (Likert score from 0 to 4, with a higher score being more satisfied), adapted FGSIS,28 Transgender Congruence Scale (TCS),31 and Body Image Satisfaction Scale (BISS)13,15,19,20,32 (Table 3).13–23,26–31

The common transgender surgery options included were (1) facial reconstructive surgery, (2) chest or “top” surgery, and (3) genital or “bottom” surgery. Facial reconstructive surgery aims to make facial features more masculine or feminine—chest or top surgery to remove breast tissue for a more masculine appearance or enhance breast size and shape for a more feminine appearance and genital or bottom surgery to transform and reconstruct the genitalia.

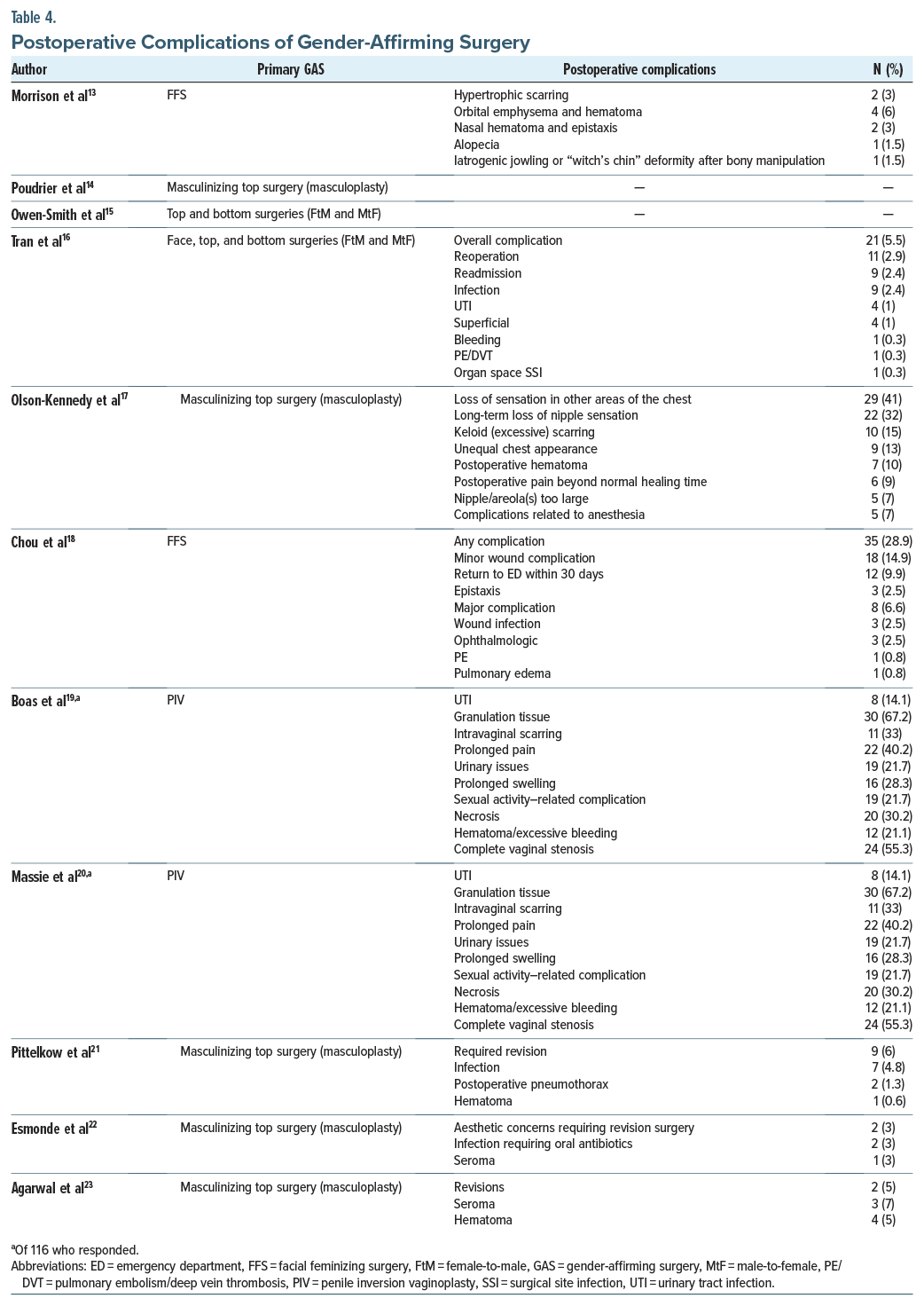

Three studies13,16,18 assessed the FFS of the participants. The FFS included scalp advancement, cranioplasty, brow lift/contouring, rhinoplasty, upper lip lift, mandibuloplasty, mandibular contouring, genioplasty, chondrolaryngoplasty, hairline lowering, hair transplantation, brow/frontal sinus setback, thyroid cartilage reduction, facelift, otoplasty, blepharoplasty, fat grafting, and various other procedures to help feminize the face.13,18 In the studies in which participants were male and female (gender assigned at birth),15,16 both top and bottom surgeries were done, which included top surgeries (eg, mastectomy or breast augmentation), partial bottom surgeries (eg, hysterectomy without vaginectomy or orchiectomy without vaginoplasty), and definitive bottom surgeries (eg, vaginectomy or vaginoplasty).15,16 The most common complications for surgery were major and minor wound complications, wound infection, hematoma, required revision, hypertrophic scarring, deformity, granulation tissue, scarring, vaginal stenosis, necrosis, prolonged pain, urinary tract infection (UTI), deep venous thrombosis, pulmonary embolism, and loss of nipple sensation13,16–21,23 (Table 4).13–23

DISCUSSION

The DSM-5-TR provides 2 criteria for defining GD described as a marked incongruence between one’s experienced/expressed gender and assigned gender of at least 6 months’ duration, along with association with clinically significant distress or impairment in social, occupational, or other key areas of functioning.2 Research suggests that individuals who undergo treatment for GD at a younger age have lower suicidal ideation than those who get GAS at a later age.33

GD treatment includes hormonal therapy, GAS, and psychological counseling. In this article, we specifically reviewed GAS as a part of treatment for GD. Literature that assesses the effect of GAS on GD is sparse. Many studies or literature have explored quality of life and patient satisfaction after surgery, showing improvement in GD after specific surgeries or surgeries in transgender males or females, not both.

Our review evaluated 11 studies that concluded that GD improved or resolved along with other mental health disorders, eg, alcohol use, tobacco smoking, and suicidal ideation or suicide attempt. Akhavan et al34 reported that quality of life improved after vaginoplasty. Patients also reported satisfaction with GAS and with their sexual health after GAS.34 Another review35 done in adolescents and adults reported that overall postsurgical body satisfaction was reported in 60% of transgender males (40% felt neutral) and 100% of transgender females. The authors35 reported a reduction in GD after GAS and that the number of GAS procedures directly corresponded with improvement in dysphoria. Depression, suicidality, and anxiety rates also showed improvement post-GAS.35 In a systematic review and meta-analysis of quality of life and psychosocial outcomes in transsexual people,36 researchers verified that sex reassignment with hormonal interventions was more likely to correct GD, psychological functioning and comorbidities, sexual function, and overall quality of life than sex reassignment without hormonal interventions. However, there is a low level of evidence for this.36 The most frequent type of surgery in our review was FFS, followed by chest-affirming and penile inversion vaginoplasty (PIV) surgeries.

Male-to-Female Surgeries

Face surgeries (facial feminization surgeries). We found that FFS significantly improved quality of life and GD, while another study34 reported that facial feminization significantly improved quality-of-life measures, but they did not measure presurgical and postsurgical GD.

Morrison et al13 used the FFS outcome score to determine satisfaction with their FFS. Another review36 reported the use of many validated instruments like the Short-Form Health Questionnaire, Body Image Scale,37 Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale,38 Sheehan Disability Scale (validated in the general population),39 and TCS (validated in the transgender population). Notably, 1 study in this review also used computed tomography and 3-dimensional photography to quantify postsurgical changes objectively.

Chou et al18 reported complications with FFS, and the most common were minor wound complications (14.9%) and epistaxis (2.5%), with a return to the emergency department rate of 9.9%. Morrison et al13 reported hypertrophic scarring, orbital emphysema, and hematoma in 4 of 20 patients. Another review40 reported serious but temporary complications like facial numbness in 6 studies, with a reoperation rate of 4.1%.

Top surgeries (chest-affirming surgeries). We found that male-to-female chest-affirming surgeries improved GD and depression rates after GAS. Akhavan et al34 also found a similar finding, with improvements in BREAST-Q and breast satisfaction and psychosocial and sexual well-being post-GAS.

One study15 used the TCS to measure body congruence, a validated scale to measure a transgender person’s level of comfort with gender identity, and the BISS to measure body image satisfaction, a subset of the previously validated revised physical self-perception profile.41 In the review by Oles et al,40 the only validated measure used to assess outcomes for chest feminization was the BREAST-Q (1 study). However, the BREAST-Q is not validated in the transgender population.40 Capsular contracture, implant extrusion, and major hematoma were some of the complications.40

Bottom surgeries. Current vaginoplasty techniques include PIV, intestinal segment, nongenital skin flaps and/ or grafts, and peritoneal flaps. While Akhavan et al34 suggest that patients report up to 80% satisfaction with PIV surgery and postoperative sexual function, an inverse association exists between the severity of complications and patient satisfaction. In 3 of 4 studies,15,16,19,20 the PIV surgery improved GD. Hadj-Moussa et al42 found that in selected patients, GAS alleviated GD. In a review of GAS in adolescent transgender females, of 5 articles reviewed, 3 found that females who underwent vaginoplasty reported alleviation of GD and improved psychological functioning.35

In our review, studies measured postoperative satisfaction with PIV using the online 20-question adapted FGSIS,28 TCS,31 and BISS.15,16,19,20,32 Oles et al43 found that 75 studies used an outcomes instrument to measure postoperative results. Forty studies used ad hoc instruments, while 35 used instruments validated only in the cisgender population. Some of the scales used were the Female Sexual Function Index,44 FGSIS,28 and BISS.32

Massie et al20 noted common complications such as granulation tissue, intravaginal scarring, complete vaginal stenosis, and other minor complications. Oles et al43 found that the intraoperative rectal injury rate was 2.4%, with injuries to the urethra, bladder, or vasculature only occasionally reported. The incidence of wound dehiscence was 12.0%, and the incidence of major infection was 2.1%.43

Female-to-Male Surgeries

Face surgeries (facial masculinizing surgeries). Patients with GD may desire masculine facial features that cannot be achieved with hormone therapy alone. Literature on facial masculinizing surgery is extremely sparse, and the outcome studies of such surgeries are even less common. Of 15 studies included in a 2019 review,45 only 2 reported outcomes of facial masculinizing surgery. Although the studies in the review did not use a quantifiable approach, the patients were satisfied overall with facial masculinizing surgeries.45

No studies in our review used instruments to measure GD pre-and postfacial masculinization surgeries. Another review45 of facial masculinization surgery also reported that no questionnaires were used to assess surgical benefits but overall reported positive patient outcomes and no complications.

Top surgeries (chest-affirming surgeries). Seven studies14–17,21–23 assessed female-to-male chest-affirming surgeries and showed improvement in GD in 6 studies.14,15,17,21–23 Akhavan et al34 showed that patient satisfaction and quality-of-life improvement are high, with significant improvement in BODY-Q scores46 postoperatively. In a review of adolescent transgender men with GD,35 GAS reduced GD significantly and improved psychological functioning in patients undergoing bilateral mastectomy or chest wall masculinizing procedures.

The studies in our review used various scales to assess GD postsurgically. Poudrier et al14 used a self-made survey, Owen-Smith et al15 used the TCS,31 Agarwal et al23 used the BREAST-Q29 and BUT-A30 scales, and Olson-Kennedy et al17 developed and used the CDS.17 In another review,40 10 validated instruments were used including the BODY-Q chest module,46 BREAST-Q, BUT-A, and ad hoc questionnaires (1 study).

Most complications were infection, hematoma, postoperative pneumothorax, seroma, surgical revisions, temporary/permanent loss of nipple sensation, loss of sensation in other areas of the chest, and unequal chest appearance.17,21 In the study by Oles et al,40 the rate of major hematoma of the breast per patient was 3.9%, with a rate of reoperation secondary to complications of 6.2%. A review34 of all GAS types reported that chest masculinizing surgeries reported the same risk profile as mastectomy in cisgender males and females with a reoperative rate of 3.2%. Hematoma as a complication is more commonly seen in minimal access techniques.34

Bottom surgeries. One study15 observed that bottom surgeries significantly improved GD among patients. Similarly, Akhavan et al34 found that patients who underwent phalloplasty reported up to 85% satisfaction. Three of five studies reviewed by Sayegh et al45 reported improvement in GD after some type of bottom surgery (phalloplasty, hysterectomy, and ovariectomy). Another review43 reported 89.6% patient satisfaction with phalloplasty, 91.3% reported satisfaction with metoidioplasty, and 2 of 23 studies reported overall satisfaction with zero regrets.

Owen-Smith et al15 used the TCS31 to measure GD postoperatively. In another review,43 13 instruments used in 15 studies either were not formally developed or were not validated in transgender individuals, including the Patient Observer Scar Assessment Scale47 and International Prostate Symptom Score48 for phalloplasty.

Infection, UTI, and pulmonary embolism/deep vein thrombosis are some of the complications noted by Tran et al.16 Akhavan et al34 found that with metoidioplasty, urological complications are common, while stricture and testicular complications were less common. Some dissatisfied patients converted to phalloplasty postoperatively. Risks of phalloplasty included urethral stricture, urethral fistula, and partial and total flap loss. Similarly, another review43 reported complications such as urethral issues and incontinence with phalloplasty. In addition, complications of metoidioplasty included urinary fistulas as well. Other complications of hysterectomy/oophorectomy/colpectomy were urinary retention, UTI, urinary frequency, and pain.

Genital confirmation surgery was more common in white transgender males than white transgender females.49 Most of the participants had used hormonal therapies before affirmation surgeries.49 The prevalence of GAS in transgender males was 42%–54%, while that in transgender females was around 28%.50

Among Asians, due to reluctance and conservative behaviors regarding sex, the population was rare to present to the health care site and had higher dropout rates than whites regarding GAS.51 Among Koreans in the United States, cost, negative experiences in health care settings, lack of specialized health care professionals and facilities, and social stigma against transgender people were some of the barriers preventing them from safe and accessible gender-affirming therapies.51

Other scales used to assess GD were the Utrecht Gender Dysphoria Scale52 (UGDS) and the Gender Identity/Gender Dysphoria Questionnaire for Adolescents and Adults53 (GIDYQ-AA). The UGDS assesses GD regarding gender identity and gender role, while the GIDYQ-AA includes subjective, somatic, social, and sociolegal aspects.54 Olson-Kennedy et al17 developed and used the CDS17 to assess GD before surgery. The CDS measured physical functioning, hygiene and exercise, intimate partnerships and dating, perception of gender, and disruption of the future. Another review55 used the CDS to assess GD and found that among transmasculine individuals who underwent chest-reforming surgeries, the satisfaction levels were as high as 97%, while the regret rate was <1%. Unger56 corroborated that hormonal therapy is integral to treating GD during transition. It showed a positive outcome in patients with GD.

The same was confirmed by Telang,57 who stated that forehead contouring and jaw reshaping remained the most requested among all procedures. In most of the studies, GAS had a positive outcome, except for 2 studies that did not mention the improvement in GD.16,18 The same was concluded by Telang,57 who found that all patients who underwent GAS reported satisfaction with the overall outcome, with an improvement in the feeling of congruence. Also, the mental health of people who received GAS improved (as measured by the Kessler Psychological Distress Scale58). GAS also improved binge alcohol use, tobacco smoking, and suicidal ideation or suicide attempt.59 A dissatisfaction rate of 7.7% among transgender females after GAS was observed in one study,60 mainly because of the large clitoris, recurrent fistulas, and no depth in the neovagina. Also, 26.92% of participants had undergone aesthetic touch-ups in rectovaginal fistulas and vaginal and urethral structures to repair complications.60 Among transgender females, labiaplasty followed by clitoroplasty was the most required cosmetic revision surgical procedure according to Unger.56 The quality-of-life measure 15 years post-GAS with the King’s Health Questionnaire61 found quality of life to be lower in the domains of general health, role limitation, physical limitation, and personal limitations.62

Bustos et al63 found that the most common complications were fistulas, stenosis/or strictures, tissue necrosis, and prolapse. The patient regret rate was around 2% among other studies.63 Sigurjonsson et al64 found that most major complications, such as deep infection, rectovaginal fistula, and pulmonary embolism, were rare. Minor complications affected approximately 25% of patients. The most common minor complications were bleeding and infection.64

Postoperative complications could be prevented by patient education. To avoid secondary procedures, surgeons could work with the patient ahead of time to avoid noncompliance.65 Preoperative planning is important to recognize the lack of available local genital tissue (genital hypoplasia caused by early puberty blockers and shortened penile skin tube after aggressive circumcision) and to have an informed discussion with the patient. Another study66 stated that race was an independent predictor of important short-term postoperative outcomes in GAS and found that black patients had more 30-day postoperative short-term complications than their white counterparts. A few measures that were used to assess GD postsurgery included the FGSIS,28 TCS,31 and BISS.15,19,20,32

Limitations

FFS has a smaller body of literature, though interest in FFS among academic plastic surgeons is rapidly increasing. We also did not include nonsurgical feminization with laser hair removal, fillers, and chemoparalytics in our considerations. However, FFS is not limited to feminization, and no literature on facial masculinization procedures was available at the time of this writing. Despite its popularity among transgender females, breast augmentation has the least data of all GAS procedures. In our review, most of the population was white. While a few studies show disparities between the races, the literature indicates that black patients suffer from higher rates of postoperative complications than their white counterparts, and the surgery rates of Asian individuals are lower than their white counterparts.

The studies in our review had a short (6 months to a maximum of 2 years) follow-up post-GAS, which may not be sufficient to examine long-term outcomes and patient satisfaction with GAS and the resolution of GD. Many of the studies lack randomization and control groups, making the evidence level weaker and the results susceptible to bias. Our study included individuals based only in the United States; hence, it is difficult to extrapolate this evidence to the transgender population in other countries.

Future Implications

Further investigations are required to explore the impact of race and ethnicity on GAS. Additionally, there is a need for more studies employing standardized assessments to evaluate the overall quality of life following GAS. Thus far, there is a lack of standardized and validated satisfaction questionnaires specifically designed for the transgender population. It is a common practice to administer World Health Organization quality-of-life surveys before and after reconstructive surgeries to alleviate GD in transgender patients. Surgeons conducting such operations should consider implementing this approach in the future. Ongoing studies are focused on developing a comprehensive patient-reported outcome measure for the transgender and gender-diverse community. A reliable metric is essential to accurately assess and replicate patient-reported outcomes for transgender and gender-diverse individuals after undergoing GAS.

To enhance patient response rates and capture a broader range of answers, future studies should consider integrating free-text responses alongside questionnaires. Furthermore, it is essential to conduct additional research to investigate the long-term outcomes of revision labiaplasty and clitoroplasty comprehensively. This can be achieved through prospective studies with large sample sizes and extended follow-up periods, enabling a thorough evaluation of these aspects before and after gender-confirming treatment.

A crucial aspect that requires assessment is the rate of regret or disappointment among transgender adolescents who undergo GAS, such as chest wall masculinization in transgender males or vaginoplasty in transgender females, before reaching the age of 18 years. A comparative analysis should be conducted between those who undergo these procedures at an earlier stage and those who opt for them later in life. Additionally, it is important to explore and evaluate alternative surgical techniques for transgender females who have undergone puberty suppression during early puberty and may have inadequate penile tissue for PIV. Finally, comparing surgical complication rates between transgender adolescents expressing a desire and meeting the eligibility criteria for GAS before the age of 18 years and those who undergo surgery in adulthood is of significant relevance.

CONCLUSION

People with GD feel trapped in the wrong body, their minds and bodies are uncoordinated, and they are always looking for liberation and rehabilitation. Our study shows that the effectiveness of gender reassignment surgery in treating GD has encouraging implications. Gender reassignment surgeries should be affordable and supported by insurance companies for children aged <18 years to reduce the development of not only GD but also depression, anxiety, and the risk of suicide. The postoperative complications could be reduced with better surgical techniques. Many of the studies included in our literature review primarily analyzed white demographics. This shows that GD has been understudied, underdiagnosed, and undertreated in the underrepresented minorities in the United States, potentially due to religious or cultural views. One of the primary limitations noted in most of the research on transgender issues and GD is the lack of inclusion of ethnic and racial minorities within samples; it is common for studies to report samples that are 80% or more white. Another key limitation identified in our study is the relatively short follow-up duration in the studies we reviewed, ranging from 6 months to a maximum of 2 years post-GAS. This limited follow-up period may not provide a comprehensive understanding of the long-term outcomes and patient satisfaction associated with GAS, as well as the resolution of GD. It is crucial to recognize that the effects of these surgeries may continue to evolve over time. Therefore, future research should prioritize extended follow-up periods to provide a more accurate assessment of the sustained benefits and potential challenges faced by individuals post-GAS.

Article Information

Published Online: November 11, 2025. https://doi.org/10.4088/PCC.23r03677

© 2025 Physicians Postgraduate Press, Inc.

Submitted: November 19, 2023; accepted February 8, 2024.

To Cite: Bhela JS, Saboor S, Ansari M, et al. Analysis of gender-affirming surgeries to improve gender dysphoria and quality of life in the United States. Prim Care Companion CNS Disord. 2025;27(6):23r03677.

Author Affiliations: Department of Psychiatry, Windsor University School of Medicine, Cayon, West Indies (Bhela); Department of Social and Behavioral Sciences, Harvard T.H. Chan School of Public Health, Boston, Massachusetts (Saboor); Department of Psychiatry, SUNY Upstate Medical University, Syracuse, New York (Ansari); Department of Psychiatry, Sri Guru Ram Das Institute of Medical Sciences & Research, Amritsar, India (Bhullar); Department of Psychiatry, Topiwala National Medical College, Mumbai, India (Agarwal); Department of Psychiatry, Jinnah Sindh Medical University, Karachi, Pakistan (Ashok); Department of Family Medicine, Lower Bucks Hospital, Bristol, Pennsylvania (Amin); Department of Physiology, Seth GS Medical College Mumbai, Parel, India (Subhedar); Department of Psychiatry, Dow University of Health and Sciences, Karachi, Pakistan (Javed); Department of Psychiatry, Department of Psychiatry, BronxCare Health System, New York, New York (Kainth); Department of Psychiatry, Texas Tech University Health Science Center at Permian Basin, Midland, Texas (Yadav, Jain); Department of Psychiatry, Wake Forest University, Winston-Salem, North Carolina (Shah); Department of Psychiatry, Boston Children’s Hospital/Harvard Medical School, Boston, Massachusetts (Mansuri).

Corresponding Author: Maliha Ansari, MBBS, SUNY Upstate Medical Univeristy, 750 E Adams St, Syracuse, NY 13210 ([email protected]).

Relevant Financial Relationships: None.

Funding/Support: None.

ORCID: Maliha Ansari: https://orcid.org/0000-0001-5410-5738

Clinical Points

- Individuals who undergo treatment for gender dysphoria (GD) at a younger age, including gender-affirming surgery (GAS), may experience lower rates of suicidal ideation compared to those who opt for surgery at a later age, underscoring the potential mental health benefits of timely interventions for GD.

- GAS, particularly facial feminization surgery, chest- affirming surgeries, and bottom surgeries, has been associated with significant improvements in GD, mental health, and overall quality of life, with patients reporting high levels of satisfaction and reduced rates of depression, anxiety, and suicidal ideation after surgery.

- It is essential to recognize the influence of race and ethnicity on access to and outcomes of gender-affirming therapies; barriers such as cultural views, health care disparities, and reluctance to seek care may disproportionately affect individuals from diverse backgrounds.

References (66)

- Fisher AD, Ristori J, Morelli G, et al. The molecular mechanisms of sexual orientation and gender identity. Mol Cell Endocrinol. 2018;467:3–13. PubMed CrossRef

- American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders. 5th ed, text rev. (DSM-5-TR). American Psychiatric Association;2022.

- Ristori J, Cocchetti C, Romani A, et al. Brain sex differences related to gender identity development: genes or hormones? Int J Mol Sci. 2020;21(6):2123. PubMed CrossRef

- Newcomb ME, Hill R, Buehler K, et al. High burden of mental health problems, substance use, violence, and related psychosocial factors in transgender, non-binary, and gender diverse youth and young adults. Arch Sex Behav. 2020;49(2):645–659. PubMed CrossRef

- Johns MM, Lowry R, Andrzejewski J, et al. Transgender identity and experiences of violence victimization, substance use, suicide risk, and sexual risk behaviors among high school students – 19 states and large urban school districts, 2017. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2019;68(3):67–71. PubMed CrossRef

- à Campo J, Nijman H, Merckelbach H, et al. Psychiatric comorbidity of gender identity disorders: a survey among Dutch psychiatrists. Am J Psychiatry. 2003;160(7):1332–1336. PubMed CrossRef

- Cohen-Kettenis PT, van Goozen SH. Sex reassignment of adolescent transsexuals: a follow-up study. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 1997;36(2):263–271. PubMed CrossRef

- Tordoff DM, Wanta JW, Collin A, et al. Mental health outcomes in transgender and nonbinary youths receiving gender-affirming care. JAMA Netw Open. 2022;5(2):e220978. PubMed CrossRef

- Nguyen HB, Chavez AM, Lipner E, et al. Gender-affirming hormone use in transgender individuals: impact on behavioral health and cognition. Curr Psychiatry Rep. 2018;20(12):110. PubMed CrossRef

- Claahsen-van der Grinten H, Verhaak C, Steensma T, et al. Gender incongruence and gender dysphoria in childhood and adolescence-current insights in diagnostics, management, and follow-up. Eur J Pediatr. 2021;180(5):1349–1357. PubMed CrossRef

- Plastic Surgery Statistics. American society of plastic surgeons; 2023. Accessed May 16, 2023. https://www.plasticsurgery.org/news/plastic-surgery-statistics

- El-Hadi H, Stone J, Temple-Oberle C, et al. Gender-affirming surgery for transgender individuals: perceived satisfaction and barriers to care. Plast Surg. 2018;26(4):263–268. PubMed CrossRef

- Morrison SD, Capitán-Cañadas F, Sánchez-García A, et al. Prospective quality-of-life outcomes after facial feminization surgery: an international multicenter study. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2020;145(6):1499–1509. PubMed CrossRef

- Poudrier G, Nolan IT, Cook TE, et al. Assessing quality of life and patient-reported satisfaction with masculinizing top surgery: a mixed-methods descriptive survey study. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2019;143(1):272–279. PubMed CrossRef

- Owen-Smith AA, Gerth J, Sineath RC, et al. Association between gender confirmation treatments and perceived gender congruence, body image satisfaction, and mental health in a cohort of transgender individuals. J Sex Med. 2018;15(4):591–600. PubMed CrossRef

- Tran BNN, Epstein S, Singhal D, et al. Gender affirmation surgery: a synopsis using American college of surgeons national surgery quality improvement program and national inpatient sample databases. Ann Plast Surg. 2018;80(4 suppl 4):S229–S235. PubMed CrossRef

- Olson-Kennedy J, Warus J, Okonta V, et al. Chest reconstruction and chest dysphoria in transmasculine minors and young adults: comparisons of nonsurgical and postsurgical cohorts. JAMA Pediatr. 2018;172(5):431–436. PubMed CrossRef

- Chou DW, Tejani N, Kleinberger A, et al. Initial facial feminization surgery experience in a multicenter integrated health care system. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2020;163(4):737–742. PubMed CrossRef

- Boas SR, Ascha M, Morrison SD, et al. Outcomes and predictors of revision labiaplasty and clitoroplasty after gender-affirming genital surgery. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2019;144(6):1451–1461. PubMed CrossRef

- Massie JP, Morrison SD, Van Maasdam J, et al. Predictors of patient satisfaction and postoperative complications in penile inversion vaginoplasty. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2018;141(6):911e–921e. PubMed CrossRef

- Pittelkow EM, Duquette SP, Rhamani F, et al. Female-to-male gender-confirming drainless mastectomy may be safe in obese males. Aesthet Surg J. 2020;40(3):NP85–NP93. PubMed CrossRef

- Esmonde N, Heston A, Jedrzejewski B, et al. What is nonbinary and what do I need to know? A primer for surgeons providing chest surgery for transgender patients. Aesthet Surg J. 2019;39(5):NP106–NP112. PubMed CrossRef

- Agarwal CA, Scheefer MF, Wright LN, et al. Quality of life improvement after chest wall masculinization in female-to-male transgender patients: a prospective study using the BREAST-Q and Body Uneasiness Test. J Plast Reconstr Aesthet Surg. 2018;71(5):651–657. PubMed CrossRef

- Manne S, Nereo N, DuHamel K, et al. Anxiety and depression in mothers of children undergoing bone marrow transplant: symptom prevalence and use of the Beck depression and Beck anxiety inventories as screening instruments. J Consult Clin Psychol. 2001;69(6):1037–1047. PubMed CrossRef

- Beck AT, Epstein N, Brown G, et al. An inventory for measuring clinical anxiety: psychometric properties. J Consult Clin Psychol. 1988;56(6):893–897. PubMed CrossRef

- Alsarraf R. Outcomes research in facial plastic surgery: a review and new directions. Aesthet Plast Surg. 2000;24(3):192–197. PubMed CrossRef

- Alsarraf R, Larrabee WF, Anderson S, et al. Measuring cosmetic facial plastic surgery outcomes: a pilot study. Arch Facial Plast Surg. 2001;3(3):198–201. PubMed CrossRef

- Herbenick D, Reece M. Development and validation of the female genital self-image scale. J Sex Med. 2010;7(5):1822–1830. PubMed CrossRef

- Pusic AL, Klassen AF, Scott AM, et al. Development of a new patient-reported outcome measure for breast surgery: the BREAST-Q. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2009;124(2):345–353. PubMed CrossRef

- Cuzzolaro M, Vetrone G, Marano G, et al. The Body Uneasiness Test (BUT): development and validation of a New Body Image Assessment Scale. Eat Weight Disord. 2006;11(1):1–13. PubMed CrossRef

- Kozee HB, Tylka TL, Andrew Bauerband L, et al. Measuring transgender individuals comfort with gender identity and appearance: development and validation of the Transgender Congruence Scale. Psychol Women Quart. 2012;36(2):179–196. CrossRef

- Lindwall M, Asci H, Hagger MS. Factorial validity and measurement invariance of the Revised Physical Self-Perception Profile (PSPP-R) in three countries. Psychol Health Med. 2011;16(1):115–128. PubMed CrossRef

- Wernick JA, Busa S, Matouk K, et al. A systematic review of the psychological benefits of gender-affirming surgery. Urol Clin North Am. 2019;46(4):475–486. PubMed CrossRef

- Akhavan AA, Sandhu S, Ndem I, et al. A review of gender affirmation surgery: what we know, and what we need to know. Surgery. 2021;170(1):336–340. PubMed CrossRef

- Mahfouda S, Moore JK, Siafarikas A, et al. Gender-affirming hormones and surgery in transgender children and adolescents. Lancet Diabetes Endocrinol. 2019;7(6):484–498. PubMed CrossRef

- Moisés da Silva GV, Lobato MIR, Silva DC, et al. Male-to-female gender-affirming surgery: 20-year review of technique and surgical results. Front Surg. 2021;8:639430. PubMed CrossRef

- Whoqol Group. Development of the WHOQOL: rationale and current status. Int J Ment Health. 1994;23(3):24–56.

- Snaith RP. The Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale. Health Qual Life Outcomes. 2003;1:29. PubMed CrossRef

- Sheehan Disability Scale (SDS). Sheehan Disability Scale (SDS). Harm Research Institute; 2016. Accessed June 2, 2023. https://harmresearch.org/about-us/david-v-sheehan-md-mba/sheehan-scales-and-structured-diagnostic-interviews/sheehan-disability-scale-sds/

- Oles N, Darrach H, Landford W, et al. Gender affirming surgery: a comprehensive, systematic review of all peer-reviewed literature and methods of assessing patient-centered outcomes (part 1: breast/chest, face, and voice). Ann Surg. 2022;275(1):e52–e66. PubMed CrossRef

- Fox K, Corbin C. The physical self-perception profile: devlopment and preliminary validation. J Sport Exerc Psychol. 1989;11:408–430. CrossRef

- Hadj-Moussa M, Ohl DA, Kuzon WM. Feminizing genital gender-confirmation surgery. Sex Med Rev. 2018;6(3):457–468.e2. PubMed CrossRef

- Oles N, Darrach H, Landford W, et al. Gender affirming surgery: a comprehensive, systematic review of all peer-reviewed literature and methods of assessing patient-centered outcomes (part 2: genital reconstruction). Ann Surg. 2022;275(1):e67–e74. PubMed CrossRef

- Rosen R, Brown C, Heiman J, et al. The Female Sexual Function Index (FSFI): a multidimensional self-report instrument for the assessment of female sexual function. J Sex Marital Ther. 2000;26(2):191–208. PubMed CrossRef

- Sayegh F, Ludwig DC, Ascha M, et al. Facial masculinization surgery and its role in the treatment of gender dysphoria. J Craniofac Surg. 2019;30(5):1339–1346. PubMed CrossRef

- Klassen AF, Kaur M, Poulsen L, et al. Development of the BODY-Q chest module evaluating outcomes following chest contouring surgery. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2018;142(6):1600–1608. PubMed CrossRef

- Lenzi L, Santos J, Raduan Neto J, et al. The patient and observer scar assessment scale: translation for Portuguese language, cultural adaptation, and validation. Int Wound J. 2019;16(6):1513–1520. PubMed CrossRef

- Barry MJ, Fowler FJ, O’Leary MP, et al. The American urological association symptom index for benign prostatic hyperplasia. The measurement committee of the American urological association. J Urol. 1992;148(5):1549–1557;discussion 1564. PubMed CrossRef

- James SE, Herman HL, Rankin S, et al. The Report of the 2015 U.S. Transgender Survey. National Center for Transgender Equality;2016.

- Kailas M, Lu HMS, Rothman EF, et al. Prevalence and types of gender-affirming surgery among A sample of transgender endocrinology patients prior to state expansion of insurance coverage. Endocr Pract. 2017;23(7):780–786. PubMed CrossRef

- Lee H, Park J, Choi B, et al. Experiences of and barriers to transition-related healthcare among Korean transgender adults: focus on gender identity disorder diagnosis, hormone therapy, and sex reassignment surgery. Epidemiol Health. 2018;40:e2018005. PubMed CrossRef

- McGuire JK, Berg D, Catalpa JM, et al. Utrecht Gender Dysphoria Scale – Gender Spectrum (UGDS-GS): construct validity among transgender, nonbinary, and LGBQ samples. Int J Transgend Health. 2020;21(2):194–208. PubMed CrossRef

- Deogracias JJ, Johnson LL, Meyer-Bahlburg HFL, et al. The Gender Identity/ Gender Dysphoria Questionnaire for Adolescents and Adults. J Sex Res. 2007;44(4):370–379. PubMed CrossRef

- Schneider C, Cerwenka S, Nieder TO, et al. Measuring gender dysphoria: a multicenter examination and comparison of the Utrecht Gender Dysphoria Scale and the Gender Identity/Gender Dysphoria Questionnaire for Adolescents and Adults. Arch Sex Behav. 2016;45(3):551–558. PubMed CrossRef

- Mañero I, Arno AI, Herrero R, et al. Cosmetic revision surgeries after transfeminine vaginoplasty. Aesthetic Plast Surg. 2023;47(1):430–441. PubMed CrossRef

- Unger CA. Hormone therapy for transgender patients. Transl Androl Urol. 2016;5(6):877–884. PubMed CrossRef

- Telang PS. Facial feminization surgery: a review of 220 consecutive patients. Indian J Plast Surg. 2020;53(2):244–253. PubMed CrossRef

- Kessler RC, Andrews G, Colpe LJ, et al. Short screening scales to monitor population prevalences and trends in non-specific psychological distress. Psychol Med. 2002;32(6):959–976. PubMed CrossRef

- Almazan AN, Keuroghlian AS. Association between gender-affirming surgeries and mental health outcomes. JAMA Surg. 2021;156(7):611–618. PubMed CrossRef

- Monteiro Petry Jardim LM, Cerentini TM, Lobato MIR, et al. Sexual function and quality of life in Brazilian transgender women following gender-affirming surgery: a cross-sectional study. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2022;19(23):15773. PubMed CrossRef

- Kelleher CJ, Cardozo LD, Khullar V, et al. A new questionnaire to assess the quality of life of urinary incontinent women. Br J Obstet Gynaecol. 1997;104(12):1374–1379. PubMed CrossRef

- Kuhn A, Bodmer C, Stadlmayr W, et al. Quality of life 15 years after sex reassignment surgery for transsexualism. Fertil Steril. 2009;92(5):1685–1689.e3. PubMed CrossRef

- Bustos SS, Bustos VP, Mascaro A, et al. Complications and patient-reported outcomes in transfemale vaginoplasty: an updated systematic review and meta-analysis. Plast Reconstr Surg Glob Open. 2021;9(3):e3510. PubMed CrossRef

- Sigurjonsson H, Rinder J, Möllermark C, et al. Male to female gender reassignment surgery: surgical outcomes of consecutive patients during 14 years. JPRAS Open. 2015;6:69–73. CrossRef

- Laungani A, Sapin-Leduc A, Belanger M, et al. Strategies to prevent and mitigate common complications in gender affirming penile inversion vaginoplasty. Plast Aesthetic Res. 2022;9(6):40. CrossRef

- Trilles J, Chaya BF, Brydges H, et al. Recognizing racial disparities in postoperative outcomes of gender affirming surgery. LGBT Health. 2022;9(5):333–339. PubMed CrossRef

Enjoy this premium PDF as part of your membership benefits!