Lessons Learned at the Interface of Medicine and Psychiatry

The Psychiatric Consultation Service at Massachusetts General Hospital sees medical and surgical inpatients with comorbid psychiatric symptoms and conditions. During their twice-weekly rounds, Dr Stern and other members of the Consultation Service discuss diagnosis and management of hospitalized patients with complex medical or surgical problems who also demonstrate psychiatric symptoms or conditions. These discussions have given rise to rounds reports that will prove useful for clinicians practicing at the interface of medicine and psychiatry.

Prim Care Companion CNS Disord 2025;27(6):25f04010

Author affiliations are listed at the end of this article.

Have you ever wondered what triggers inflammatory bowel diseases (IBDs)? Have you been uncertain about how IBDs impact the lives of your patients? Have you puzzled over how your patients can manage their gastrointestinal (GI) symptoms and make use of psychotropic agents? If you have, the following case vignette and discussion should prove useful.

CASE VIGNETTE

Ms A, a 19-year-old college freshman, developed abdominal pain, cramping, and bloody stools and sought help from her primary care physician (PCP). Her medical history was notable for asthma, irritable bowel syndrome (IBS), and an episode of major depression treated with cognitive-behavioral therapy (CBT). Her medications included occasional use of an albuterol inhaler. At her most recent visit, her scores on the Generalized Anxiety Disorder-7 (GAD-7)1 and the Patient Health Questionnaire-9 (PHQ-9)2 were 16 and 6, respectively. She also reported a family history of hypothyroidism and multiple sclerosis.

Ms A recognized she was chronically anxious as a child, although her anxiety abated in adolescence. Overall, her transition to college had been smooth. She established a supportive social network and enjoyed her classes. However, over the past 6 months, she experienced more abdominal pain, diarrhea, and fatigue, which she assumed were symptoms of her IBS. She felt anxious and on edge, ruminating at nighttime about stressors she had never been troubled by before, including her class grades and relationships with friends. These thoughts kept her from being able to gain restful sleep. Her GI symptoms also worsened during her menses, which had become more irregular. Approximately 1 month after her GI symptoms began, she visited an urgent care center where infectious causes of her diarrhea were ruled out. However, over the past month, her bloody diarrhea persisted, and she lost 10 lb; this worsened her anxiety and she had difficulty eating and sleeping. Given the progressive nature of her symptoms and their impact on her mental health, her roommate suggested that she seek help.

DISCUSSION

What Are IBDs, and How Are They Diagnosed?

IBDs represent a group of chronic relapsing remitting autoimmune medical conditions in which inflammation of the digestive tract is the result of an abnormal immune response to gut flora.3–6 IBDs predominantly include Crohn’s disease (CD) and ulcerative colitis (UC), which are distinguished from one another by the pattern, depth, and location of inflammation. Inflammation in UC is continuous, localized to the large intestine (colon and rectum), and restricted to the innermost layer of the colon, or mucosa.3–6 However, inflammation in CD, known as a “skip lesion,” is interspersed with healthy sections of bowel.6 Moreover, inflammation in CD can occur anywhere in the gut from mouth to anus and extends through all layers of the colon (ie, it is transmural).6 When individuals have findings that are inconsistent with both CD and UC, the diagnostic term indeterminate colitis is used, demonstrating that while CD and UC have distinct features, they also have substantial overlap.6,7

Symptoms consistent with IBD include persistent diarrhea (associated with blood or mucus, urgency, abdominal pain, rectal bleeding), fever, weight loss, and fatigue. Afflicted individuals may also present with constipation when rectal inflammation is present. Nausea and vomiting are also quite common.7–9

The number of people living with IBDs in the United States is estimated at 1.6 million, with 785,000 individuals having CD and 910,000 having UC. In Europe, 2 million people have IBD.3 Approximately 70,000 new cases of IBD are diagnosed in the United States every year.6 While the prevalence of IBD is higher in Western countries, the incidence has been rising in South America, Asia, Africa, and Eastern Europe.3 Changes in the pattern of the incidence of IBD point to multifactorial contributions to the pathogenesis of the disease: genetic susceptibility plays a critical role, with genome-wide association studies demonstrating more than 160 loci that are associated with UC and CD. However, the risk contribution from these has been demonstrated to be less than 25%.8 Thus, environmental influences are important contributors to IBD’s pathophysiology.8 Particularly, the intestinal microbiome (which can be altered by diet, antibiotics, age, and mental health conditions) can cause IBD directly through immune dysregulation or alterations in mucosal barrier function, which results in inappropriate immune responses to intestinal organisms.3,8

The distribution of IBD is bimodal: although it is commonly diagnosed in individuals before the age of 35 years, a second peak occurs after the age of 60.9 While CD is slightly more common among females, UC is equally prevalent in both sexes.10 On physical examination, those with IBDs may experience tachycardia, anxiety, fever, and dehydration. Occult blood may be present on a digital rectal examination. Findings of fistulas, abscesses, strictures, or even rectal prolapse are associated with CD.7,9 The diagnosis of IBD is complex: patients may present atypically and have an overlap of symptoms with other disease processes, and there is no single test that definitively establishes the diagnosis of IBD or reliably differentiates CD and UC from one another.7 Thus, many patients experience a delay between the onset of their symptoms and their diagnosis,7 despite obtaining laboratory markers and conducting imaging studies and endoscopy.9 A complete blood cell count may reveal microcytic anemia, leukocytosis, or thrombocytosis.9 Markers such as erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR) and high-sensitivity C-reactive protein (hs-CRP) provide an assessment of systemic inflammation, while fecal calprotectin levels measure intestinal inflammation.9 Stool studies can rule out the presence of ova and parasitic organisms.9 Evaluation with endoscopy, through esophagogastroduodenoscopy and/or colonoscopy–provided biopsies, can confirm the diagnosis. Imaging studies such as computed tomography (CT) and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) are frequently used to assess complications of IBDs (eg, bowel perforation or obstruction and fistulas).9

What Triggers IBDs, and What Are Their Risk Factors?

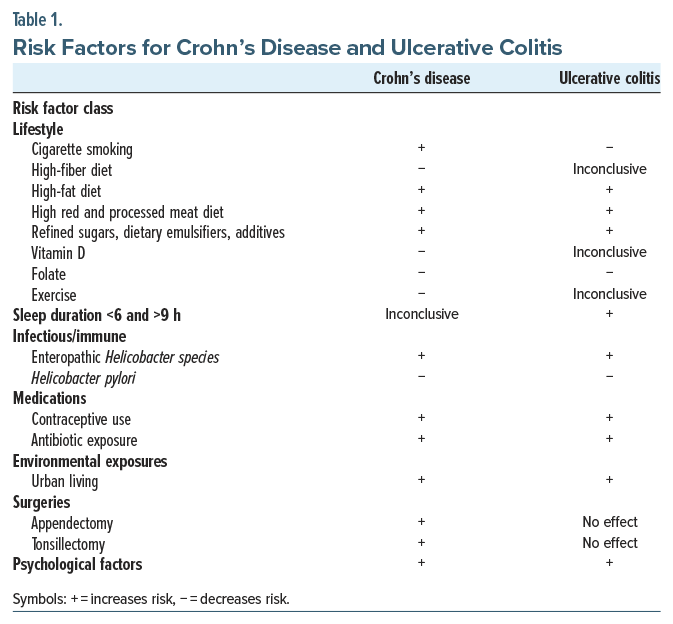

Several clinical risk factors have been associated with the development of IBDs and can be broadly organized into lifestyle, infectious/immune, medications, environmental exposures, surgeries, and psychological factors (Table 1).11 Importantly, CD and UC are affected differently by some of these risk factors.

A few of the most common lifestyle factors that impact the development of IBDs are cigarette smoking, physical activity, diet, and dysregulated sleep. Interestingly, current cigarette smoking is a risk factor for the development and exacerbation of CD; however, it appears to be somewhat protective against the development of UC.12,13 Consistent with this finding, smoking cessation increases UC disease activity and the risk for hospitalization14 but reduces the risk of developing CD.13 Physical activity similarly has discordant effects on CD and UC, such that it has been associated with a decrease in the risk of developing CD, but not UC.15 Epidemiologic studies also point to several dietary factors that may affect the risk of developing IBD. Dietary factors that reduce the risk of IBDs include eating a high-fiber diet (for CD), having high vitamin D levels (for CD), and having a high intake of folate (for CD and UC). Dietary factors that increase the risk of IBDs include consuming a high-fat diet (for CD and UC), eating red and processed meat (for CD and UC), and using refined sugars, dietary emulsifiers, or additives (which tend to be more common in “Western” diets) (for CD and UC).11,16,17 Finally, duration—less than 6 hours/night or greater than 9 hours/night—is associated with an increased risk of developing UC but not CD,18 although self-reported poor sleep quality has been associated with greater disease activity in those with UC and CD.19

Several additional identified risk factors fall within the categories of infectious/immune response, medications, environmental exposures, and surgeries. Of these, factors that increase IBD risk include certain infections (eg, with non-Helicobacter pylori–like enterohepatic Helicobacter species) (for both UC and CD), oral contraceptive use (for both UC and CD), antibiotic exposure (for both UC and CD), urban living (for both UC and CD), appendectomy (for CD), and tonsillectomy (for CD). Factors found to decrease IBD risk include infection with Helicobacter pylori (for both UC and CD).11

Finally, data regarding the relationships among psychological factors (eg, stress, depression, anxiety) and IBDs are mixed. Stress, for example, is often perceived by those with IBD as a trigger for their disease, yet associations among stress and IBD onset and disease course have not been consistently identified across studies, and further prospective research into their risk is needed. Regarding depression and anxiety, which are relatively common among individuals with IBD,20 emerging research suggests that there is a bidirectional relationship between these psychiatric comorbidities and IBD, such that risks for depression and anxiety are higher before and after IBD diagnosis.21

Although the pathophysiology of IBDs remains poorly understood, an examination of the risk factors for IBDs points to several underlying mechanisms that contribute to disease onset. The pathogenesis of IBDs is thought to arise primarily from a dysregulated response of the mucosal immune system to intestinal microbiota and microbial products in individuals with genetic susceptibility. A growing body of evidence suggests that there may be differences in epithelial barrier function as well as intestinal microbial composition; the latter, at least in part, is likely mediated by dietary and environmental risk factors.22,23 Collectively, these risk factors (ie, lifestyles, infections, medications, environmental, surgical, psychological) for IBD probably exert their effects by affecting intestinal inflammation and microbiota composition, which interact with individual genetic elements to produce a pathologic immune response.22,23 Notably, the IBDs are probably even more heterogeneous than just the 2 main subtypes (ie, CD versus UC), and our understanding of the underlying mechanisms of these 2 subtypes, as well as their divergent clinical presentations, remains limited.23

Which Conditions Look Like IBDs?

Not surprisingly, many conditions can present with the same nonspecific clinical symptoms of IBDs (eg, abdominal pain, diarrhea, rectal bleeding). Common mimics of IBDs include intestinal infections (eg, salmonella), ischemic colitis, radiation colitis, vasculitis, drug-induced enteritis, or colitis (eg, related to nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs), colorectal cancer, IBS, celiac disease, gluten sensitivity, and lactose intolerance. In the case of IBDs, there can also be nonspecific intestinal and systemic symptoms (eg, weight loss, fever, nausea/vomiting, and fatigue), as well as extraintestinal manifestations (EIMs) (eg, arthritis). The differential diagnosis for the most common presenting symptoms of IBDs (eg, abdominal pain) is broad, and it highlights the importance of a careful examination and diagnostic workup, with diagnosis based on a combination of clinical symptoms and results of serologic testing, imaging studies, endoscopy, and histopathology.24,25

What Is the Prognosis for IBDs?

IBDs are chronic illnesses without a cure, although several treatments effectively manage symptoms. Patients with both UC and CD typically experience intermittent exacerbations with alternating periods of symptomatic remission, with other factors impacting disease course and the risk of relapse. Unfortunately, even with appropriate treatment, nearly half of those with CD and nearly one-sixth of those with UC require surgical intervention or intestinal resection after 10 years, although treatment advances over the past several decades have decreased this risk significantly.26

IBDs are also associated with an increased risk of colorectal cancer development as compared to individuals without chronic colitis.3,5,6 The longer the duration with which the individual lives with IBD, the greater their risk of being diagnosed with colorectal cancer.6 Such cancer can also have aggressive histological characteristics and lower curative rates. Due to the elevated risk of colorectal cancer, increased surveillance is advised with more frequent colonoscopies than the general population (eg, every 1 to 2 years, 8 years after the diagnosis of an IBD).6

What Can Complicate IBDs, and How Can Their Course Be Monitored?

Patients suffering from IBDs can experience intestinal complications and EIMs. These can occur throughout the duration of disease course; therefore, the European Crohn’s and Colitis Organization (ECCO) recommends consistent monitoring (which often involves clinical evaluations, endoscopy or imaging, and biomarkers). In UC, active disease monitoring also includes laboratory markers (eg, CRP and fecal calprotectin); for those who respond to medical therapy, mucosal healing (MH) should be determined endoscopically or by fecal calprotectin 3–6 months after treatment initiation.27 All patients newly diagnosed with CD should undergo a small bowel assessment via intestinal ultrasound, magnetic resonance enterography, or capsule endoscopy. In those with active CD, a clinical and biochemical response to treatment should be established within 12 weeks and within 6 months after initiation of therapy. Endoscopic or cross-sectional reassessment should be considered in cases of relapse, persistent disease activity, new unexplained symptoms, and before switching therapies.27

Intestinal complications (eg, perianal fistulas, which occur in approximately 14%–38% of patients with CD) are common and portend a more complicated disease course and a more difficult surgical recovery.28 Fistulas can be simple or complex (ie, with abscesses, rectovaginal fistulas, or anorectal strictures). Perianal abscesses can be the first presentation of CD in healthy individuals, and a thorough baseline clinical examination of the perianal area should be performed in all newly diagnosed patients at the time of ileocolonoscopy.27

Strictures or stenoses (localized, persistent luminal narrowing’s that are complicated by functional issues, including bowel dilation or obstructive symptoms) occur in one-fourth of individuals with CD.28 An MRI scan or an intestinal ultrasound (IUS) is recommended for detection.27 Perforated bowel often develops due to other intestinal complications of IBDs. A spontaneous free perforation is infrequent in CD, arising in 1%–2% of those with CD. When a perforation is suspected, a CT scan is indicated in individuals with acute abdominal pain and an established IBD diagnosis.27

Toxic megacolon (TM), which can occur in either CD or UC, is defined as an acute dilatation of the transverse colon (greater than 6 cm in diameter) and a loss of haustration on radiologic examination in a case of severe colitis.29 Although the prevalence is low, but not precisely known, it increases with age. The incidence of TM is higher in patients with UC (8%–10%) than in those with CD (2.3%). Approximately half of those with TM develop this complication in the first 3 months of their IBD diagnosis.29 TM occurs in roughly 5% of individuals with a severe attack of UC, and outcomes from TM are poor, with an in-hospital mortality of 7.9%.29 The most common presenting symptom of TM is severe bloody diarrhea. In the setting of clinical decline, patients can also develop hypotension, tachycardia, fever, diffuse abdominal tenderness with distention, and sluggish bowel sounds. Baseline and serial abdominal x-rays are then performed to follow the progression of colonic dilatation, while in select cases, a CT scan could be used to screen for its complications.27,29

Clostridium difficile infection is common in individuals with IBD, and it is associated with worse outcomes, including increased colectomy rates and more postoperative complications. All patients with a suspected flare of IBD should be investigated for an infection, including exclusion of Clostridium difficile infection.27

Colitis-associated colorectal cancer is a chronic intestinal manifestation of IBD. Patients with IBD have approximately 20 times the risk for developing colon cancer compared with those in the general population.30 A screening colonoscopy should be offered 8 years after the onset of symptoms to all patients to reassess the extent of their disease and exclude dysplasia. For those with strictures or dysplasia that has been detected within the past 5 years, primary sclerosing cholangitis (PSC), or extensive colitis with severe active inflammation, surveillance colonoscopy should be completed annually.27

The frequency of EIM in IBD ranges from 6% to 50%, and it may be present in 10%–24% of patients at the time of their IBD diagnosis; in up to one-fourth of those with IBD, EIM can predate intestinal symptoms.28,31,32 Patients can be affected by more than 1 EIM at a time, with up to one-fourth of patients suffering from 2 or more manifestations. EIMs may be more frequent in early-onset IBD and in younger individuals.31

IBD is considered a minor to moderate independent risk factor for venous thrombotic events (VTEs), which are more than twice as common in individuals with IBD compared to those in the general population. Risk factors for VTE in patients with IBD include active disease state, hospitalization, and surgery. Post-hospitalization and post-operative IBD patients can be considered for thromboprophylaxis.32

Nearly half (46%) of patients with IBD suffer from musculoskeletal EIMs. Axial involvement or spondyloarthritis (SpA) can occur along with peripheral involvement. SpA often involves persistent inflammatory low back pain and can be diagnosed via an MRI scan.31,32 In the case of ankylosing spondylitis, bilateral sacroiliitis can develop, and up to half of patients with CD show asymptomatic sacroiliitis on imaging. It may take years from symptom onset to the development of radiographic signs of sacroiliitis. Patients with known IBD and back pain should be considered for an anteroposterior radiograph of the pelvis to evaluate for sacroiliitis, while an MRI scan is a more sensitive tool.31,32

Enthesitis (inflammation of the insertion of tendons, ligaments, and joint capsule into bone) is common and can occur in 7%–50% of adults with IBD. Enthesitis can occur both axially and peripherally; chronic enthesitis can lead to functional disability and structural changes such as osteopenia, bone cortex irregularities, erosions, soft tissue calcifications, and abnormal new bone formation. Enthesitis is often missed or overlooked by clinicians, although it can be detected at an earlier stage with ultrasound of the affected area.31

Peripheral joint involvement or peripheral SpA occurs in between 5% and 15% of patients with UC and in 10%–20% of those with CD. Diagnosis is clinical, often with oligoarticular asymmetric arthritis, which affects less than 5 joints and preferentially involves large joints (eg, ankles, knees, hips, wrists, elbows, and shoulders). A normal ESR does not preclude active disease, nor are rheumatologic diagnostic tests often positive.31

Anemia is one of the most common complications of IBD; it is often multifactorial due to combinations of nutritional deficiency and the sequelae of chronic diseases. Iron deficiency anemia and anemia of chronic disease are the leading causes of anemia in IBD, present in 30%–90% of patients with anemia and IBD.32,33 As per ECCO guidelines, screening should occur every 6–12 months when the disease is quiescent and every 3 months when the disease is active.32 The diagnosis is recommended based on differing ferritin levels that correspond to differing levels of inflammation; ferritin is an acute phase reactant. In the quiescent phase of the disease, levels <30 μg/L are consistent with iron deficiency anemia, while serum ferritin levels of 30–100 μg/L can indicate iron deficiency and anemia of chronic disease when the disease is active; transferrin <16% and serum ferritin >100 μg/L indicate anemia of chronic disease.32,33 Monitoring for activity-induced fatigue is a helpful indication that hemoglobin is low. Significantly low hemoglobin levels are below 12 g/dL in females and 13 g/dL in males.

Malnutrition occurs in up to 85% of patients with IBD both in active stages and during remission, with a lower rate of malnutrition in those with quiescent disease than in active disease states. It also occurs more often in cases of UC than in cases of CD.33 At time of diagnosis, the ECCO recommends investigating for malnutrition and malabsorption, which should be reassessed at regular intervals.27 Patients with IBD and malnutrition have poor outcomes (eg, prolonged hospitalizations, complicated perioperative courses, and higher mortality rates).33 Causes of poor oral intake (including anorexia, abdominal pain, nausea, impaired absorption, direct loss, or increased energy expenditure that is not coupled with increased intake) are numerous. The most common micronutrient deficiencies in IBD are vitamin B12, folate, iron, and vitamin D. Up to one-fourth (22%) of patients with CD suffer from vitamin B12 deficiency when the diagnosis is based on serum levels. Causes most commonly include ileal disease or resection, fistulas, small bowel bacterial overgrowth, reduced intake, increased physiologic requirements, protein-losing enteropathy, and hepatic dysfunction. ECCO guidelines recommend checking vitamin B12 levels at least annually or when macrocytosis is present, in the absence of thiopurine use.32,33 Up to 80% of patients with CD present with low serum folate levels. Risk factors for deficiency include active disease and sulfasalazine or methotrexate treatment.32,33

Erythema nodosum (EN) is characterized by painful erythematous–violaceous subcutaneous plaques or nodules that are usually 1–5 cm in diameter, often located symmetrically on extensor surfaces of the lower extremities but also on the thighs and forearms. EN is the most common skin disorder in IBD, with a prevalence of 5%–15% in CD and 2%–10% in UC. When it is present, the aim is to control the underlying intestinal disease activity.31,32

PSC is a chronic cholestatic liver disease characterized by inflammation and fibrosis of the bile ducts that confers a significant risk of end-stage liver disease, malignancy, and mortality. Its prevalence ranges from 2% to 8%, and patients with UC are at higher risk. Patients with a persistent elevation of cholestatic liver enzymes and symptoms of cholestasis (eg, pruritus or prominent perihilar lymphadenopathy) should undergo a magnetic resonance cholangiopancreatography.32

How Can IBDs Be Managed?

According to the official practice recommendations written by the American College of Gastroenterology, the management goal for UC is a “sustained and durable period of steroid-free remission, accompanied by appropriate psychosocial support, normal health-related quality of life, prevention of hospitalization and surgery, and prevention of cancer.”34(p.384) Once the diagnosis of UC has been established, the severity, extent, and prognosis can be determined so that health care providers can recommend treatment options and monitoring schedules.34 These recommendations are similar to those made for patients with CD; however, CD can extend beyond the colon and lead to complications (eg, fistulae, strictures, EIMs), thus disease location, phenotype, and disease-associated complications should be considered.35 The goals of treatment for UC and CD include treating the diseases early, achieving and maintaining remission, and facilitating mucosal healing, as this is a more reliable marker for improved long-term outcomes (eg, reduced hospitalizations, avoidance of bowel damage and colectomy).34–36 Treatment decisions for both UC and CD are based on patient and providers’ preferences and may involve stand-alone or combinations of medications or surgical interventions.34,35,37,38 Over-the-counter medications (eg, antidiarrheal medication or laxatives/stool softeners, nutritional therapies and supplements) and behavioral health supports may also be recommended.37

Pharmacologic treatments for IBD may be used in combination or alone depending on patients’ diagnoses, disease activity, treatment targets, side effects, comorbidities, and access to these medications.37 According to the Crohn’s Colitis Foundation, medications for IBDs generally fall within 5 categories: aminosalicylates, corticosteroids, immunomodulators, antibiotics, biologic therapies, and JAK inhibitors.37 Aminosalicylates contain 5-aminosalicylic acid and work by inhibiting pathways that produce proinflammatory substances; thus, they work on the lining of the GI tract to decrease inflammation. Corticosteroids affect the body’s ability to initiate and maintain the inflammatory process and to keep the immune system in check. These agents are effective for the short-term control of active disease; however, because of their side effects, they are not recommended for long-term use. Immunomodulators modify the body’s immune system to limit its ability to cause inflammation. Biologic therapies are bioengineered drugs that target specific molecules involved in the inflammatory process. These therapies are antibodies that target the action of other inflammation-inducing proteins. Antibiotics may also be prescribed to address infections that may arise and are also used to treat perianal CD and pouchitis (which is inflammation of the J-pouch). Finally, JAK inhibitors are orally administered agents that are absorbed into the blood stream and can quickly induce or maintain remission for individuals with UC.36,37

Although therapies and treatments for UC and CD are continuing to be developed, a subset of patients with IBD requires surgery. Recommendations for surgery differ between UC and CD patients in large part due to variability in the disease severity as well as the subsequent risks of disease recurrence and complications.38–42

For those with UC, the surgical removal of the colon is considered curative.38,42 Approximately 15%–20% of individuals with UC require surgery to remove their colon.42 Indications for surgical treatment of UC can be broadly classified as elective, urgent, or emergency surgery. Elective surgery may be offered when the disease is refractory to medical management or when there is dysplasia, invasive malignancy, or palliation of EIMs.40 Urgent or emergency surgery may be required when severe colitis is refractory to medication and the individual is increasingly unwell, develops TM, or develops a bowel perforation or a major hemorrhage.39 Depending on the indications for surgery, as well as the patients’ preferences, surgery for UC can be nonrestorative or restorative. The current gold-standard surgery for UC is panproctocolectomy (with an ileal pouch anal anastomosis [IPAA]), which is performed in 2 or 3 stages, depending on the patient’s condition.38,40,42 During the procedure, the entire colon is removed, and the ileum of the remaining small intestine is sewn into a J-shaped pouch that will store waste before defecation. At the same time, the small intestine is used to form a temporary ileostomy, which is used while the J-pouch heals. Eight to 12 weeks after the first stage, the patient returns, and the temporary ileostomy is taken down and the small intestine is reattached.42 In a third-stage procedure, the first stage involves the removal of the large intestine and creation of the temporary ostomy, the second surgery is done to create the J-pouch, and the final surgery involves taking down the ileostomy and creating a reattachment.42 Nonrestorative options involve removing part of or the entire colon, while creating a permanent ostomy.38

While surgery is considered “curative” for patients with UC (since the disease is limited to the colon), this is not the case for those with CD. Surgery for CD is primarily indicated for those who develop fistulae, strictures, or abscesses; the most common surgical approach for those with CD is intestinal resection,39 although a small percentage of those with CD (whose disease is limited to the colon) may undergo IPAA surgery.40,42 Roughly 90% of patients with CD who undergo surgery develop a recurrence within 1 year of surgery, and a repeated intestinal resection is required in one-fourth of patients within 5 years and in one-third of patients within 10 years.39

What Is the Impact of Psychotropics on IBDs?

As disturbances in the gut-brain axis have been identified as playing a role in chronic IBD, evidence supports treatments that target gut-brain pathways (eg, psychotropic medications) in the management of IBD.43 Symptoms of depression and anxiety are highly prevalent in IBD, affecting approximately one-fourth and one-third of patients with IBD, respectively.20 When depression and IBD coexist, quality of life suffers, and adverse outcomes (eg, IBD relapse, hospitalization, and surgery) arise.44 The benefits of antidepressants extend beyond the improvement of mental health and quality of life, to favorably impacting the course and outcome of IBD by altering disease activity. Psychotropics also facilitate the management of pain and fatigue, as well as disturbances of sleep and gut motility observed in those with IBD.45

Unfortunately, the precise mechanisms by which antidepressants improve outcomes for IBD remain unknown. Apart from their effects on monoamine neurotransmitters and the downregulation of receptors that can treat comorbid mental disorders, antidepressants have a neuromodulator role that mediates visceral sensitivity, gut motility and secretion and has immunoregulatory and anti-inflammatory effects, while shifting the composition of gut microbiota.45

Several classes of antidepressant medication are used for the treatment of IBD. Selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs) (eg, fluoxetine, sertraline, escitalopram, paroxetine, citalopram, and fluvoxamine) are first-line agents for the treatment of depressive disorders and anxiety, although data establishing their superiority in comorbid psychiatric disorders and IBD are limited. Overall, SSRIs are better tolerated than tricyclic antidepressants (TCAs). Common side effects include fatigue, nausea, headache, as well as alterations of sleep, appetite, and weight. The antidepressant, sertraline may more commonly induce bowel disturbance (eg, diarrhea). Antidepressants can be discontinued prematurely due to patient propensity for experiencing adverse effects in those with IBD46 or due to anxiety about developing side effects, indicating the value of scheduling more frequent primary care visits to alleviate such worries.47

Serotonin-norepinephrine reuptake inhibitors (SNRIs) (eg, duloxetine, venlafaxine) inhibit reuptake of both serotonin and norepinephrine and have been demonstrated to be helpful when pain is related to inhibition of norepinephrine reuptake. Their tolerability is comparable to SSRIs, with nausea and constipation as common GI side effects.

TCAs (eg, amitriptyline, imipramine, protriptyline) work through inhibition of serotonin and norepinephrine reuptake. Although TCAs are less commonly prescribed for the treatment of depression and anxiety than SSRIs (due to differences in tolerability), TCAs continue to be used in the management of painful neuropathies, migraine headaches, and IBS. Their broader histaminergic and cholinergic receptor actions are responsible for dry mouth, sedation, constipation, weight gain, and blurred vision. Tachycardia, hypotension, or rare seizures or cardiac arrhythmias are additional side effects.

Other antidepressants (eg, mirtazapine) work through reuptake inhibition of serotonin or norepinephrine. Mirtazapine reduces nausea, stimulates appetite, and promotes sleep, with little propensity for interfering with sexual functioning. Tianeptine, structurally classified as a TCA, but with some different pharmacologic properties, has some evidence backing use in IBD.48

Despite their potential benefits in IBD, the evidence base supporting the use of antidepressants is of poor quality. Of the few controlled trials that have examined antidepressant effects in those with IBDs, duloxetine, venlafaxine, and tianeptine have been beneficial for symptoms of anxiety, depression, and clinical disease activity in IBD.48–50 The only randomized controlled trial (N = 26) that examined fluoxetine in IBD failed to demonstrate a significant benefit in either of these domains but noted some effects on immune functions.51 The role of additional psychotropics in IBD remains limited to the treatment of comorbid psychiatric disorders.

How Can One Alter One’s Lifestyle to Mitigate Flares of IBD?

The American Gastroenterological Association’s clinical practice guidelines provide expert opinions on best practices regarding nutrition in IBD.52 The Mediterranean diet (which is rich in a variety of fresh fruits and vegetables, monounsaturated fats, complex carbohydrates, and lean proteins and is low in ultra-processed foods, added sugar, and salt) continues to be the most beneficial diet for overall health and general well-being in those with IBD. No diet has consistently been found to reduce the rate of IBD flares in adults. A diet low in red and processed meat may reduce UC flares, but it has not reduced relapse rates in those with CD.52 Research employing patient questionnaires has shown that a high intake of meat, especially red and processed meat, protein, alcoholic beverages, sulfur, and sulfate, increased the likelihood of a flare.53 In individuals with CD, a diet higher in total fat, saturated fat, and monounsaturated fatty acids and a higher ratio of omega-6 to omega-3 fatty acids were associated with disease relapses.54 A low fermentable oligosaccharides, disaccharides, monosaccharides, and polyols diet, while not contributing to IBD remission, may reduce functional GI symptoms in IBD with careful attention paid to nutritional adequacy.55

Overall, a high-fiber diet is beneficial for general health, and it contributes to diversity of the gut microbiome. Further, high-fiber diets may improve remission rates in CD.56 In addition, carefully chewing, cooking, and processing of fruits and vegetables to a soft, less fibrinous consistency may help individuals with IBD who have intestinal strictures tolerate a wider variety of plant-based foods and fiber.52

Although there is no clear association between caffeine intake and progression of IBD symptoms,57 data suggest that caffeine consumption may be associated with worsening of functional GI symptoms in those with IBD,58 and it may contribute to a perception of worse symptoms in those with IBD.59 Reduced alcohol60 and carbonated drink consumption and cigarette smoking, as well as maintenance of adequate levels of folate and vitamin D have also been recommended.11

Physical exercise should be encouraged in those with IBD who have functional GI symptoms.55 Structured exercise programs may also reduce disease-related activity, and improve fatigue, muscular function, body composition, cardiorespiratory fitness, bone mineral density, and psychological well-being.61

To manage GI accidents (eg, incontinence), individuals should be prepared by traveling with a GI emergency kit (which includes spare underwear, pants, baby wipes, and toilet paper).62 Many states also have a version of Restroom Access Act, which requires businesses to provide public access to restrooms with proof of an eligible illness.

Lifestyle changes (including physical exercise, implementation of the Mediterranean diet, and reducing cigarette smoking, alcohol use, and carbonated drink intake, while maintaining adequate nutritional status, vitamin D levels, and folate levels) as well as psychological assistance may improve the quality of life in those with IBD.

What Types of Psychological Assistance Can Help Those With IBDs?

Psychotherapy (including CBT, acceptance and commitment therapy, and mindfulness-based interventions) improves quality of life in individuals with IBD.63 CBT enhances the quality of life and decreases anxiety and depression in those with IBD.64 Acceptance and commitment therapy for IBD decreases anxiety and increases quality of life in those with IBD.65 Mindfulness-based interventions significantly improve short-term outcomes (eg, stress, mindfulness, CRP levels, and health-related quality of life) in those with IBD. Studies have shown that these benefits were maintained over the long term for stress and mindfulness.66 One clinical trial showed a reduction in the frequency of IBD flares with behavioral therapy (hypnotherapy for UC, CBT for CD) compared to placebo, indicating a possible benefit on disease-related activity.67 Some patients find peer support groups helpful; however, according to a recent meta-analysis, there was no significant evidence for the improvement of psychological well-being with these interventions, likely due to the heterogeneity of the experience.68

What Novel Treatments Are On the Horizon for Psychiatric Disorders Co-Occurring With IBDs?

Given the high prevalence of psychiatric comorbidities (eg, anxiety, depression, and trauma-spectrum disorders) with IBD, there is increasing recognition of treatments that might modulate inflammatory pathways of IBD as well as the psychiatric disorders that often exacerbate them. Existing treatments (eg, TCAs, SSRIs, and SNRIs) have limited evidence that supports modulation beyond mood and anxiety symptoms, and many patients remain refractory to the benefits of these medicines.

Psychedelics (compounds that produce profound disruptions of subjectivity and perceptual distortions) represent an intriguing area of potential promise given their actions that range from the molecular to the level of neural circuitries.69 Several psychedelic drugs (including psilocybin, lysergic acid diethylamide [LSD], and 3,4-methylenedioxymethamphetamine) are in late clinical trials for depression, anxiety, and posttraumatic stress disorder, respectively.70 Current clinical and research applications of psychedelics advocate for the use of these agents in the context of psychotherapy or psychological support (called psychedelic-assisted therapy [PAT]) before, during, and after the psychedelic-enhanced sessions that facilitate efficacy and minimize the risk of adverse experiences.70

PATs are intriguing as a potential application for IBD, not only due to a growing evidence base that supports their efficacy in treating the psychiatric conditions most often comorbid with IBD but also due to their mechanisms of action via areas of the brain associated with pain processing (eg, the anterior cingulate cortex, insula, and somatosensory cortex), as demonstrated in recent neuroimaging studies of LSD.71 In addition, some psychedelics also appear to possess direct, potent anti-inflammatory properties that may have implications for IBD-mediated inflammation.72,73 Finally, recent preclinical work has shown that psychedelics can modulate neuroimmune reactions in the amygdala, reversing stress-induced fear behavior and monocyte accumulation (via astrocytic and meningeal pathways), suggesting their potential to treat inflammation-linked psychiatric symptoms in chronic illnesses.74 While studies have not yet applied PATs to IBD, a clinical trial is currently underway that explores the effects of psilocybin-assisted therapy on the brain and the gut in individuals with IBS that may yield valuable data to guide future research pathways in psychedelic-related gastroenterology research.75 In addition, studies have found that PATs can reduce pain in other disorders, such as fibromyalgia.76

Several emerging treatments seek to target psychiatric and physical symptoms in IBD. Digital therapeutics (health technologies that range from interactive psychoeducation, gamified behavioral modification platforms, and telemedicine) are also emerging as promising adjuncts to traditional IBD care, with some trials showing promise.77 Although a systematic review showed that digital health interventions did not reduce overall disease activity or relapse rates, results demonstrated that health care utilization and health care costs were superior in comparisons of digital interventions and placebo.78 Vagus nerve stimulation, long used for depression, is also being explored as a treatment for both depression and gut inflammation, offering an integrated approach for individuals with IBD.79

What Happened to Ms A?

During her appointment with her PCP, Ms A received a physical exam and baseline laboratory assessment.

Ms A’s findings were notable for tachycardia and hypotension on vitals; abdominal tenderness on exam; and microcytic anemia (Hgb 10.8 g/dL), elevated CRP (18 mg/L), and increased calprotectin (>250 μg/g) on laboratory results. Ms A’s PCP referred her to a gastroenterologist, who repeated in-office screening with the GAD-7 (score of 21) and PHQ-9 (score of 12) and conducted a colonoscopy that showed an ulcerated mucosa extending from the rectum to the splenic flexure consistent with UC. Ms A’s gastroenterologist started her on oral mesalamine (4 g/day) along with rectal mesalamine enemas. Her gastroenterologist also referred her to a dietitian who provided counseling on consumption of iron-rich foods and adequate calcium and vitamin D intake and a behavioral health team, beginning with an assessment by psychology. Ms A’s evaluations prompted her to make the difficult decision to take a 1-month leave from college.

Over the course of treatment in behavioral health, Ms A engaged in CBT and mindfulness training to help her cope with distress related to UC flares. She also received an evaluation from psychiatry and began treatment with paroxetine (10 mg po QD) and trazodone (50 mg po QHS).

After 1 month, Ms A reported that her rectal bleeding had resolved, and she regained her appetite and 7 lb. Her GAD-7 score improved to 14 and PHQ-9 score to 8. She resumed classes. After 3 months, Ms A reported experiencing greater confidence about her UC diagnosis. Her GAD-7 score was now 8, and her PHQ-9 score was 3. She continued maintenance mesalamine and daily paroxetine, weaned and stopped trazodone, and attended monthly CBT sessions. Ms A’s health care team emphasized stress reduction practices and straightforward ways to maintain her diet during college. As Ms A considered her future after college, she expressed interest in establishing a support group at her college for individuals with IBDs, voicing a desire to help others to navigate the identity of having a chronic medical condition.

CONCLUSIONS

IBDs (eg, CD and UC) represent a group of chronic relapsing remitting autoimmune medical conditions in which inflammation of the digestive tract is the result of an abnormal immune response to gut flora; these disorders are distinguished from one another by the pattern, depth, and location of inflammation. Symptoms of IBDs include persistent diarrhea (associated with blood or mucus, urgency, abdominal pain, rectal bleeding), fever, weight loss, fatigue, and constipation when rectal inflammation is present. Markers (eg, ESR and hs-CRP) provide an assessment of systemic inflammation, while fecal calprotectin levels measure intestinal inflammation.

Patients with IBDs can experience intestinal (eg, perianal fistulas, strictures, TM, colitis-associated colorectal cancer) and extraintestinal complications (eg, VTEs, SpA, anemia, malnutrition, EN, sclerosing cholangitis). For those with UC, the surgical removal of the colon is considered curative, and roughly 15%–20% of individuals with UC require surgical resection of their colon. Although, a high-fiber diet is beneficial for general health, and it contributes to diversity of the gut microbiome, no diet has consistently been found to reduce the rate of IBD flares in adults.

Article Information

Published Online: November 6, 2025. https://doi.org/10.4088/PCC.25f04010

© 2025 Physicians Postgraduate Press, Inc.

Submitted: May 23, 2025; accepted July 21, 2025.

To Cite: Nadkarni A, Madva EN, Kohrman SI, et al. Talking to your patients about inflammatory bowel diseases: a guide for primary care providers. Prim Care Companion CNS Disord 2025;27(6):25f04010.

Author Affiliations: Brigham and Women’s Hospital/Harvard Medical School, Boston, Massachusetts (Nadkarni), Massachusetts General Hospital/Harvard Medical School, Boston, Massachusetts (Madva, Kohrman, Rajalakshmi, Fuss, King, Stern), Brigham and Women’s Hospital/Harvard Medical School Residency, Boston, Massachusetts (Jolivert). Nadkarni, Madva, Kohrman, Jolivert, Rajalakshmi, Fuss, and King are co-authors; Stern is senior author.

Corresponding Author: Ashwini Nadkarni, MD, Brigham and Women’s Hospital/ Harvard Medical School, Boston, Massachusetts ([email protected]).

Relevant Financial Relationships: Dr Stern has received royalties from Elsevier for editing textbooks on psychiatry. Drs Nadkarni, Madva, Kohrman, Jolivert, Rajalakshmi, Fuss, and King report no relevant financial relationships.

Funding/Support: None.

Clinical Points

- Risk factors for episodes of inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) can be broadly organized into lifestyle (eg, cigarette smoking, physical activity, diet [eg, consuming a high-fat diet], and dysregulated sleep), infection/immune response, medications, environmental exposures, surgeries, and psychological factors.

- The differential diagnosis for the most common presenting symptoms of IBDs (eg, abdominal pain) is broad, and it highlights the importance of a careful examination and diagnostic workup, with diagnosis ultimately based on a combination of clinical symptoms, and results of serologic testing, imaging studies, endoscopy, and histopathology.

- Pharmacologic treatments for IBD, used alone or in combination, generally fall within 5 categories: aminosalicylates, corticosteroids, immunomodulators, antibiotics, biologic therapies, and Janus kinase inhibitors.

- IBDs are chronic illnesses without a cure, although several effective treatments can manage symptoms.

- Psychotherapy (including cognitive-behavioral therapy, acceptance and commitment therapy, and mindfulness-based interventions) improves quality of life in individuals with IBD.

References (79)

- Spitzer RL, Kroenke K, Williams JB, et al. A brief measure for assessing generalized anxiety disorder: the GAD-7. Arch Intern Med. 2006;166(10):1092–1097. PubMed CrossRef

- Kocalevent RD, Hinz A, Brähler E. Standardization of the depression screener Patient Health Questionnaire (PHQ-9) in the general population. Gen Hosp Psychiatry. 2013;35(5):551–555. PubMed CrossRef

- Ramos GP, Papadakis KA. Mechanisms of disease: inflammatory bowel diseases. Mayo Clin Proc. 2019;94(1):155–165. PubMed CrossRef

- Guan Q. A comprehensive review and update on the pathogenesis of inflammatory bowel disease. J Immunol Res. 2019;2019(1):7247238. PubMed CrossRef

- Segal JP, LeBlanc JF, Hart AL. Ulcerative colitis: an update. Clin Med. 2021;21(2):135–139. PubMed CrossRef

- The facts about inflammatory bowel diseases. Crohnscolitisfoundation.org. [cited 2024 Mar 28]. https://www.crohnscolitisfoundation.org/sites/default/files/2019-02/Updated%20IBD%20Factbook.pdf

- Passarella A, Grewal P, Vrabie R. Diagnosis and monitoring in inflammatory bowel disease: who, when, where, and how. Inflamm Bowel Dis Pathogenesis, Diagnosis Management. 2021:25–59.

- O’Toole A, Korzenik J. Environmental triggers for IBD. Curr Gastroenterol Rep. 2014;16:1–6.

- Tontini GE, Vecchi M, Pastorelli L, et al. Differential diagnosis in inflammatory bowel disease colitis: state of the art and future perspectives. World J Gastroenterol. 2015;21(1):21–46. PubMed CrossRef

- Lungaro L, Costanzini A, Manza F, et al. Impact of female gender in inflammatory bowel diseases: a narrative review. J Pers Med. 2023;13(2):165. PubMed CrossRef

- Piovani D, Danese S, Peyrin-Biroulet L, et al. Environmental risk factors for inflammatory bowel diseases: an umbrella review of meta-analyses. Gastroenterology. 2019;157(3):647–659.e4. PubMed CrossRef

- Mahid SS, Minor KS, Soto RE, et al. Smoking and inflammatory bowel disease: a meta-analysis. Mayo Clin Proc. 2006;81(11):1462. PubMed CrossRef

- Higuchi LM, Khalili H, Chan AT, et al. A prospective study of cigarette smoking and the risk of inflammatory bowel disease in women. Am J Gastroenterol. 2012;107(9):1399–1406. PubMed CrossRef

- Beaugerie L, Massot N, Carbonnel F, et al. Impact of cessation of smoking on the course of ulcerative colitis. Am J Gastroenterol. 2001;96(7):2113–2116. PubMed CrossRef

- Khalili H, Ananthakrishnan AN, Konijeti GG, et al. Physical activity and risk of inflammatory bowel disease: prospective study from the Nurses’ Health Study cohorts. BMJ. 2013;347:f6633. PubMed CrossRef

- Sugihara K, Kamada N. Diet-microbiota interactions in inflammatory bowel disease. Nutrients. 2021;13(5):1533. PubMed CrossRef

- Christensen C, Knudsen A, Arnesen EK, et al. Diet, food, and nutritional exposures and inflammatory bowel disease or progression of disease: an umbrella review. Adv Nutr. 2024;15(5):100219. PubMed CrossRef

- Ananthakrishnan AN, Khalili H, Konijeti GG, et al. Sleep duration affects risk for ulcerative colitis: a prospective cohort study. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2014;12(11):1879–1886. PubMed CrossRef

- Ali T, Madhoun MF, Orr WC, et al. Assessment of the relationship between quality of sleep and disease activity in inflammatory bowel disease patients. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2013;19(11):2440–2443. PubMed CrossRef

- Barberio B, Zamani M, Black CJ, et al. Prevalence of symptoms of anxiety and depression in patients with inflammatory bowel disease: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2021;6(5):359–370. PubMed CrossRef

- Bisgaard TH, Allin KH, Keefer L, et al. Depression and anxiety in inflammatory bowel disease: epidemiology, mechanisms and treatment. Nat Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2022;19(11):717–726. PubMed CrossRef

- Guan Q. A comprehensive review and update on the pathogenesis of inflammatory bowel disease. J Immunol Res. 2019;2019:7247238. PubMed CrossRef

- Chang JT. Pathophysiology of inflammatory bowel diseases. NEJM. 2020;383(27):2652–2664. PubMed CrossRef

- Gecse KB, Vermeire S. Differential diagnosis of inflammatory bowel disease: imitations and complications. Lancet Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2018;3(9):644–653. PubMed CrossRef

- Chachu KA, Osterman MT. How to diagnose and treat IBD mimics in the refractory IBD patient who does not have IBD. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2016;22(5):1262–1274. PubMed CrossRef

- Frolkis AD, Dykeman J, Negrón ME, et al. Risk of surgery for inflammatory bowel diseases has decreased over time: a systematic review and meta-analysis of population-based studies. Gastroenterology. 2013;145(5):996–1006. PubMed CrossRef

- Maaser C, Sturm A, Vavricka SR, et al. ECCO-ESGAR Guideline for Diagnostic Assessment in IBD Part 1: initial diagnosis, monitoring of known IBD, detection of complications. J Crohns Colitis. 2019;13(2):144–164. PubMed CrossRef

- Rakowsky S, Papamichael K, Cheifetz AS. Choosing the right biologic for complications of inflammatory bowel disease. Expert Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2022;16(3):235–249. PubMed CrossRef

- Desai J, Elnaggar M, Hanfy AA, et al. Toxic megacolon: background, pathophysiology, management challenges and solutions. Clin Exp Gastroenterol. 2020;13:203–210. PubMed CrossRef

- Shah SC, Itzkowitz SH. Colorectal cancer in inflammatory bowel disease: mechanisms and management. Gastroenterology. 2022;162(3):715–730.e3. PubMed CrossRef

- Rogler G, Singh A, Kavanaugh A, et al. Extraintestinal manifestations of inflammatory bowel disease: current concepts, treatment, and implications for disease management. Gastroenterology. 2021;161(4):1118–1132. PubMed CrossRef

- Gordon H, Burisch J, Ellul P, et al. ECCO guidelines on extraintestinal manifestations in inflammatory bowel disease. J Crohns Colitis. 2024;18(1):1–37. PubMed CrossRef

- Weisshof R, Chermesh I. Micronutrient deficiencies in inflammatory bowel disease. Curr Opin Clin Nutr Metab Care. 2015;18(6):576–581. PubMed CrossRef

- Rubin DT, Ananthakrishnan AN, Siegel CA, et al. ACG Clinical guideline: ulcerative colitis in adults. Am J Gastroenterol. 2019;114(3):384–413. PubMed CrossRef

- Lichtenstein GR, Loftus EV, Isaacs KL, et al. ACG Clinical guideline: management of Crohn’s disease in adults. Am J Gastroenterol. 2018;113(4):481–517. PubMed CrossRef

- Rajapakse R. Inflammatory bowel disease: Pathogenesis, diagnosis, and management Humana. 1st ed; 2021.

- Crohn’s & Colitis Foundation. Understanding IBD Medications and Side Effects. Crohn’s & Colitis Foundation; 2021.

- Murphy B, Kavanagh DO, Winter DC. Modern surgery for ulcerative colitis. Updates Surg. 2020;72(2):325–333. PubMed CrossRef

- Carvello M, D’Hoore A, Maroli A, et al. Postoperative complications are associated with an early and increased rate of disease recurrence after surgery for Crohn’s disease. Dis Colon Rectum. 2023;66(5):691–699. PubMed CrossRef

- Barnes EL, Lightner AL, Regueiro M. Perioperative and postoperative management of patients with Crohn’s disease and ulcerative colitis. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2020;18(6):1356–1366. PubMed CrossRef

- Dibley L, Czuber-Dochan W, Wade T, et al. Patient decision-making about emergency and planned stoma surgery for IBD: a qualitative exploration of patient and clinician perspectives. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2018;24(2):235–246. PubMed CrossRef

- Clement E, Lin W, Shojaei D, et al. Modified 2-stage IPAA has similar postoperative complication rates and functional outcomes compared to 3-stage IPAA. Am J Surg. 2024;231:96–99. PubMed CrossRef

- Gracie DJ, Hamlin PJ, Ford AC. The influence of the brain-gut axis in inflammatory bowel disease and possible implications for treatment. Lancet Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2019;4(8):632–642. PubMed CrossRef

- Kochar B, Barnes EL, Long MD, et al. Depression is associated with more aggressive inflammatory bowel disease. Am J Gastroenterol. 2018;113(1):80–85. PubMed CrossRef

- Mikocka-Walus A, Ford AC, Drossman DA. Antidepressants in inflammatory bowel disease. Nat Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2020;17(3):184–192. PubMed CrossRef

- Jayasooriya N, Blackwell J, Saxena S, et al. Antidepressant medication use in inflammatory bowel disease: a nationally representative population-based study. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2022;55(10):1330–1341. PubMed CrossRef

- Thiwan S, Drossman D, Morris C, et al. Not all side effects associated with tricyclic antidepressant therapy are true side effects. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2009;7(4):446–451. PubMed CrossRef

- Chojnacki C, Walecka-Kapica E, Klupinska G, et al. Evaluation of the influence of tianeptine on the psychosomatic status of patients with ulcerative colitis in remission. Pol Merkur Lekarski. 2011;31(182):92–96. PubMed

- Daghaghzadeh H, Naji F, Afshar H, et al. Efficacy of duloxetine add on in treatment of inflammatory bowel disease patients: a double-blind controlled study. J Res Med Sci. 2015;20(6):595–601. PubMed CrossRef

- Liang C, Chen P, Tang Y, et al. Venlafaxine as an adjuvant therapy for inflammatory bowel disease patients with anxious and depressive symptoms: a randomized controlled trial. Front Psychiatry. 2022;13:880058. PubMed CrossRef

- Mikocka-Walus A, Hughes PA, Bampton P, et al. Fluoxetine for maintenance of remission and to improve quality of life in patients with Crohn’s disease: a pilot randomized placebo controlled trial. J Crohns Colitis. 2017;11(4):509–514. PubMed CrossRef

- Hashash JG, Elkins J, Lewis JD, et al. AGA clinical practice update on diet and nutritional therapies in patients with inflammatory bowel disease: expert review. Gastroenterology. 2024;166(3):521–532. PubMed CrossRef

- Jowett SL, Seal CJ, Pearce MS, et al. Influence of dietary factors on the clinical course of ulcerative colitis: a prospective cohort study. Gut. 2004;53(10):1479–1484. PubMed CrossRef

- Lewis JD, Abreu MT. Diet as a trigger or therapy for inflammatory bowel diseases. Gastroenterology. 2017;152(2):398–414.e6. PubMed CrossRef

- Colombel JF, Shin A, Gibson PR. AGA Clinical practice update on functional gastrointestinal symptoms in patients with inflammatory bowel disease: expert review. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2019;17(3):380–390.e1. PubMed CrossRef

- Serrano Fernandez V, Seldas Palomino M, Laredo-Aguilera JA, et al. High-fiber diet and Crohn’s disease: systematic review and meta-analysis. Nutrients. 2023;15(14):3114. PubMed CrossRef

- Saygili S, Hegde S, Shi XZ. Effects of coffee on gut microbiota and bowel functions in health and diseases: a literature review. Nutrients. 2024;16(18):3155. PubMed CrossRef

- Koochakpoor G, Salari-Moghaddam A, Keshteli AH, et al. Association of coffee and caffeine intake with irritable bowel syndrome in adults. Front Nutr. 2021;8:632469. PubMed CrossRef

- Barthel C, Wiegand S, Scharl S, et al. Patients’ perceptions on the impact of coffee consumption in inflammatory bowel disease: friend or foe?-a patient survey. Nutr J. 2015;14:78. PubMed CrossRef

- White BA, Ramos GP, Kane S. The impact of alcohol in inflammatory bowel diseases. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2022;28(3):466–473. PubMed CrossRef

- Jones K, Kimble R, Baker K, et al. Effects of structured exercise programmes on physiological and psychological outcomes in adults with inflammatory bowel disease (IBD): a systematic review and meta-analysis. PLoS One. 2022;17(12):e0278480. PubMed CrossRef

- Crohn’s and Colitis foundation. Restroom Access. Restroom Access Fact Sheet; 2024. https://www.crohnscolitisfoundation.org/sites/default/files/2019-02/UpdatedIBDFactbook.pdf.

- Paulides E, Boukema I, van der Woude CJ, et al. The effect of psychotherapy on quality of life in IBD patients: a systematic review. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2021;27(5):711–724. PubMed CrossRef

- Wang C, Sheng Y, Yu L, et al. Effects of cognitive behavioral therapy on mental health and quality of life in inflammatory bowel disease patients: a meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Behav Brain Res. 2023;454:114653. PubMed CrossRef

- Romano D, Chesterman S, Fuller-Tyszkiewicz M, et al. Feasibility, acceptability, and preliminary efficacy of acceptance commitment therapy for adults living with inflammatory bowel disease and distress. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2024;30(6):911–921. PubMed CrossRef

- Naude C, Skvarc D, Knowles S, et al. The effectiveness of mindfulness-based interventions in inflammatory bowel disease: a systematic review & meta-analysis. J Psychosom Res. 2023;169:111232. PubMed CrossRef

- Keefer L, Kiebles JL, Martinovich Z, et al. Behavioral interventions may prolong remission in patients with inflammatory bowel disease. Behav Res Ther. 2011;49(3):145–150. PubMed CrossRef

- Adriano A, Thompson DM, McMullan C, et al. Peer support for carers and patients with inflammatory bowel disease: a systematic review. Syst Rev. 2022;11(1):200. PubMed CrossRef

- King F IV, Hammond R. Psychedelics as reemerging treatments for anxiety disorders: possibilities and challenges in a nascent field. Focus. 2021;19(2):190–196. PubMed CrossRef

- King F, Nahlawi A, Stern TA. Talking to your patients about psychedelics: using an informed approach and understanding indications, risks, and benefits. Prim Care Companion CNS Disord. 2024;26(5):24f03783. PubMed CrossRef

- Maharjan D, Duan Y, Tang Y, et al. Neural correlates of pain modulation by LSD in healthy subjects: a functional MRI study. Front Neurosci. 2024;18:11334886.

- Robinson GI, Li D, Wang B, et al. Anti-inflammatory effects of serotonin receptor and transient receptor potential channel ligands in human small intestinal epithelial cells. Curr Issues Mol Biol. 2023;45(8):6743–6774. PubMed CrossRef

- Nau F Jr, Yu B, Martin D, et al. Serotonin 5-HT2A receptor activation blocks TNF-α mediated inflammation in vivo. PLoS One. 2013;8(10):e75426. PubMed CrossRef

- Chung EN, Lee J, Polonio CM, et al. Psychedelic control of neuroimmune interactions governing fear. Nature. 2025;641(8065):1276–1286. PubMed CrossRef

- Mauney E, King F IV, Burton-Murray H, et al. Psychedelic-assisted therapy as a promising treatment for irritable bowel syndrome. J Clin Gastroenterol. 2025;59(5):385–392. PubMed CrossRef

- Aday JS, McAfee J, Conroy DA, et al. Preliminary safety and effectiveness of psilocybin assisted therapy in adults with fibromyalgia: an open-label pilot clinical trial. Front Pain Res. 2025;6:1527783. PubMed CrossRef

- Oddsson SJ, Gunnarsdottir T, Johannsdottir LG, et al. A new digital health program for patients with inflammatory bowel disease: preliminary program evaluation. JMIR Form Res. 2023;7:e39331. PubMed CrossRef

- Nguyen NH, Martinez I, Atreja A, et al. Digital health technologies for remote monitoring and management of inflammatory bowel disease: a systematic review. Am J Gastroenterol. 2022;117(1):78–97. PubMed CrossRef

- Cirillo G, Negrete-Diaz F, Yucuma D, et al. Vagus nerve stimulation: a personalized therapeutic approach for Crohn’s and other inflammatory bowel diseases. Cells. 2022;11(24):4103. PubMed CrossRef

Enjoy this premium PDF as part of your membership benefits!