Find more articles on this and other psychiatry and CNS topics:

The Journal of Clinical Psychiatry

The Primary Care Companion for CNS Disorders

The Banner Alzheimer’s Institute Case Conference is a weekly event in which physicians and staff discuss challenging and/or teaching cases of patients seen at the Institute’s Memory Disorders Clinic. These conferences are attended by a multidisciplinary group that includes Banner Alzheimer’s Institute dementia specialists, community physicians (internal medicine, family medicine, and radiology), physician assistants, social workers, nurses, medical students, residents, and fellows.

About the Banner Alzheimer’s Institute

The Banner Alzheimer’s Institute located in Phoenix, Arizona, has an unusually ambitious mission: to end Alzheimer’s disease without losing a generation, set a new standard of care for patients and families, and forge a model of collaboration in biomedical research. The Institute provides high-level care and treatment for patients affected by Alzheimer’s disease, dementia, and related disorders. In addition, the Institute offers extensive support services for families and many unique and rewarding research opportunities.

Published online: April 28, 2011 (doi:10.4088/PCC.11alz01158).

Prim Care Companion CNS Disord 2011;13(2):e1-e7

© Copyright 2011 Physicians Postgraduate Press, Inc.

Authors

Roy Yaari, MD, MAS, a neurologist, is associate director of the Memory Disorders Clinic of Banner Alzheimer’s Institute and a clinical professor of neurology at the College of Medicine, University of Arizona, Tucson.

Adam S. Fleisher, MD, MAS, is associate director of Brain Imaging at the Banner Alzheimer’s Institute, a neurologist at the Institute’s Memory Disorders Clinic, and an associate professor in the Department of Neurosciences at the University of California, San Diego.

Anna Burke, MD, is a geriatric psychiatrist and dementia specialist at the Memory Disorders Clinic of Banner Alzheimer’s Institute.

Helle Brand, PA, is a physician assistant at the Memory Disorders Clinic of Banner Alzheimer’s Institute.

Jan Dougherty, RN, MS, is director of Family and Community Services at Banner Alzheimer’s Institute.

James Seward, PhD, ABPP, is a clinical neuropsychologist at Banner Alzheimer’s Institute.

Pierre N. Tariot, MD, a geriatric psychiatrist, is director of Banner Alzheimer’s Institute and a research professor of psychiatry at the College of Medicine, University of Arizona, Tucson.

Corresponding author: Roy Yaari, MD, MAS, 901 E. Willetta St, Phoenix, AZ 85006 ([email protected]).

Original material is selected for credit designation based on an assessment of the educational needs of CME participants, with the purpose of providing readers with a curriculum of CME activities on a variety of topics from volume to volume. This special series of case reports about dementia was deemed valuable for educational purposes by the Publisher, Editor in Chief, and CME Institute Staff. Activities are planned using a process that links identified needs with desired results.

To obtain credit, read the material and go to PSYCHIATRIST.COM to complete the Posttest and Evaluation online.

CME Objective

After studying this case, you should be able to:

- Use appropriate tests to diagnose early-onset dementia

Accreditation Statement

The CME Institute of Physicians Postgraduate Press, Inc., is accredited by the Accreditation Council for Continuing Medical Education to provide continuing medical education for physicians.

Credit Designation

The CME Institute of Physicians Postgraduate Press, Inc., designates this journal-based CME activity for a maximum of 1.0 AMA PRA Category 1 Creditâ„¢. Physicians should claim only the credit commensurate with the extent of their participation in the activity.

Date of Original Release/Review

This educational activity is eligible for AMA PRA Category 1 Credit through April 30, 2014. The latest review of this material was April 2011.

Financial Disclosure

All individuals in a position to influence the content of this activity were asked to complete a statement regarding all relevant personal financial relationships between themselves or their spouse/partner and any commercial interest. The CME Institute has resolved any conflicts of interest that were identified. In the past year, Larry Culpepper, MD, MPH, Editor in Chief, has been a consultant for AstraZeneca, Labopharm, Pfizer, and Trovis; has been a member of the speakers/advisory board for Merck; and has held stock in Labopharm. No member of the CME Institute staff reported any relevant personal financial relationships. Faculty financial disclosure appears at the end of the activity.

History of Presenting Illness

A 49-year-old stay-at-home mother was first noted to have cognitive changes approximately 2 years ago. At that time, she was found to be “absent minded” and was leaving lights on and misplacing items. Her activities of daily life were intact. Cognitive symptoms gradually worsened over the following year. In the last 6 months to 1 year, she began to have significant difficulties with finances and had difficulty writing checks. She stopped cooking, and there was a decline in personal care. She could not stay on track when doing tasks.

She was evaluated about 1 year ago by a local neurologist. Magnetic resonance imaging was performed at that time, which was unremarkable. Neuropsychological tests were also performed at that time with results stating, “Overall, her pattern and level of test performance revealed diffuse and severe cognitive impairment . . . far worse than could be expected in light of . . . her reported level of adaptive functioning. . . . Results are suspect for malingering and/or lack of effort and are therefore deemed invalid.” Based on these results, she was referred to a psychiatrist who found her to be significantly anxious, irritable, and agitated. Her psychiatrist considered frontotemporal dementia as a diagnosis and subsequently referred the patient to the Banner Alzheimer’s Institute for a second opinion.

At the Banner Alzheimer’s Institute, the patient’s husband reports that her anxiety levels are “through the roof.” She is increasingly repetitive with questions and stories. She is no longer able to track appointments and she misplaces items. She is having word finding difficulty. She is depressed and tearful with increasing anxiety, irritability, and agitation. She is a stay-at-home mother for their 8-year-old daughter who is in school most of the day, and when the patient is home during the day, “it is unclear what she is doing.” She has become reliant on her daughter when shopping. She has had some decline in grooming and personal care; she will shower twice a week. She continues to drive without any accidents, but she has gotten lost. She can be verbally aggressive at times but not physically aggressive. There is no psychosis.

PAST MEDICAL HISTORY

The patient has been generally healthy. She has no history of psychiatric illness.

ALLERGIES

No known drug allergies.

MEDICATIONS

The patient is not on any medications at this time. She takes a daily multivitamin.

SOCIAL HISTORY

The patient has 18 years of education with 2 master’s degrees. She worked at a high-level job until 8 years ago when her daughter was born and has been a stay-at-home mom since that time. There is no significant history of alcohol, tobacco, or illegal substance use.

FAMILY HISTORY

The patient’s maternal aunt had Alzheimer’s disease in her 70s. Her father is alive and has diabetes and dementia, possibly related to Parkinson’s disease. The patient’s mother died when the patient was 17 years old, in her mid-40s, from a bleeding ulcer.

Based on the information so far, do you think a dementia is present?

Your colleagues who attended the Banner Alzheimer’s Institute Case Conference answered as follows:

| A. Yes | 90% |

| B. No | 0% |

| C. Not enough information | 10% |

| D. Could be psychiatric | 0% |

Comments from those who chose C: In this age range, due to the history of concerns for malingering with reports of depressive features and irritability, we need more information to evaluate for psychiatric illness. Thus far in the workup, there is not enough information to distinguish between a psychiatric illness and a progressive neurodegenerative dementia.

Comments from those who chose A: The neuropsychological test results are suspect. Maybe they were looking for Alzheimer’s disease and, when they didn’ t see a typical Alzheimer’s disease pattern, called her a malingerer. According to the history, the changes have been gradual, which is more consistent with a progressive neurodegenerative dementia.

Based on the information so far, what would we expect to find on the neurologic examination?

Your colleagues who attended the Banner Alzheimer’s Institute Case Conference answered as follows:

| A. Normal | 22% |

| B. Objective neurologic findings (including frontal release signs) | 44% |

| C. Nonphysiologic findings (consistent with malingering) | 12% |

| D. Noncompliant | 0% |

| E. B and C | 22% |

The patient’s neurologic examination was unremarkable except for a positive snout reflex and broken smooth pursuits; thus, there were objective neurologic findings, albeit nonspecific. The patient was tearful during cognitive testing and intermittently during the remainder of the visit. She was mildly anxious, but answered questions appropriately, demonstrating good insight into the nature of her cognitive concerns. She was well groomed and socially appropriate.

Based on the information so far, what would you expect the MMSE score to be?

Your colleagues who attended the Banner Alzheimer’s Institute Case Conference answered as follows:

| A. 26–30 | 43% |

| B. 21–25 | 57% |

| C. 16–20 | 0% |

| D. 11–15 | 0% |

| E. Lower than 11 | 0% |

The MMSE score was 13 (Figure 1 and 2). The attendees at this case conference expected her to have a much higher score on the basis of the clinical history.

Based on the information so far, what would you expect the Montreal Cognitive Assessment score to be?

Your colleagues who attended the Banner Alzheimer’s Institute Case Conference answered as follows:

| A. 26–30 | 0% |

| B. 21–25 | 63% |

| C. 16–20 | 37% |

| D. 11–15 | 0% |

| E. Lower than 11 | 0% |

The Montreal Cognitive Assessment was not performed because of the low score on the MMSE.

Based on the information so far, what would you expect the Category Retrieval test score to be?

Your colleagues who attended the Banner Alzheimer’s Institute Case Conference answered as follows:

| A. Over 16 | 0% |

| B. 11–15 | 0% |

| C. 5–10 | 71% |

| D. 0–4 | 29% |

The patient listed 3 animals on Category Retrieval, and she had a poor clock drawing (Figure 3).

Based on the information so far, do you think this is dementia?

Your colleagues who attended the Banner Alzheimer’s Institute Case Conference answered as follows:

| A. Yes | 88% |

| B. No | 0% |

| C. Not enough information | 12% |

| D. Could be psychiatric | 0% |

Based on the information so far, what is the most likely diagnosis?

Your colleagues who attended the Banner Alzheimer’s Institute Case Conference answered as follows:

| A. Pseudodementia | 11% |

| B. Frontotemporal dementia syndrome | 56% |

| C. Alzheimer’s disease | 11% |

| D. Other (metabolic disorder, heavy metal toxicity, is the husband poisoning her?) | 0% |

| E. Dementia not otherwise specified | 22% |

Comments by those who chose B: Frontotemporal dementia is considered higher in the differential because of her young age and the confusion in the prior workup of malingering with frontotemporal dementia.

Neuroimaging is recommended for screening of dementia by the American Academy of Neurology (Knopman et al, 2001). A noncontrast head computed tomographic scan or magnetic resonance imaging scan of the brain is necessary to rule out other disorders such as vascular dementia and normal pressure hydrocephalus or other structural lesions. Current clinical dementia guidelines do not recommend routine fluorodeoxyglucose (FDG)-PET scans in dementia evaluations (Knopman et al, 2001). However, it is useful for distinguishing clinically ambiguous cases of Alzheimer’s disease versus frontotemporal dementia and is reimbursable under Medicare for this purpose. The European Federation of the Neurological Societies has recommended use of FDG-PET as part of the routine diagnostic workup of clinically questionable dementia cases (Hort et al, 2010).

Beta amyloid levels in the cerebrospinal fluid (CSF), in particular Aβ1-42 (Aβ42), have been studied as biomarkers for Alzheimer’s disease. CSF concentrations of Aβ42 are reduced by 40% to 50% in individuals with Alzheimer’s disease compared to normal controls (Thal et al, 2006). CSF tau has also been studied as a potential biomarker in Alzheimer’s disease (Hampel et al, 2004). Elevations of 2- to 3-fold of CSF total tau (t-tau) levels in patients with Alzheimer’s disease have been demonstrated in cross-sectional studies. A ratio between t-tau to Aβ42 levels in most studies results in higher sensitivity and specificity (89% and 90%, respectively) than for t-tau (81% and 91%) or Aβ42 (86% and 89%) alone (Thal et al, 2006).

Studies looking at subspecies of phosphorylated tau (p-tau) have demonstrated increased diagnostic performance compared to t-tau levels. In a study of the combination of CSF p-tau181 and Aβ42, the sensitivity was 86% at a specificity of 97% (Maddalena et al, 2003). In another study, the combination of CSF t-tau and p-tau396/404 resulted in a sensitivity of 96% at a specificity of 100% (Hu et al, 2003). CSF Aβ42 was found to be a sensitive biomarker for Alzheimer’s disease in an autopsy cohort with premorbid CSF samples, with receiver operating characteristic area under the curve of 0.913 and sensitivity for Alzheimer’s disease detection of 96.4% (Shaw et al, 2009). In an Alzheimer’s Disease NeuroImaging Initiative (ADNI) cohort, a logistic regression model for Aβ42, t-tau, and apolipoprotein E (APOE) ε4 allele count provided the best assessment delineation of mild Alzheimer’s disease. And, an Alzheimer’s disease–like baseline CSF profile for t-tau/Aβ42 was detected in 33 of 37 ADNI subjects with mild cognitive impairment who converted to probable Alzheimer’s disease during the first year of the study (Shaw et al, 2009). In addition, CSF Aβ42 levels correlate with brain atrophy in cognitively normal individuals (Fagan et al, 2009), and with accelerated rates of hippocampal atrophy in mild cognitive impairment and Alzheimer’s disease (Schuff et al, 2009).

With regard to genetic testing, APOE ε4 genotyping is not recommended for routine evaluations of suspected dementia. Autosomal dominant early-onset Alzheimer’s disease represents less than 1% of Alzheimer’s disease cases. However, it typically has an early (< 60 years) and predictable age of onset (Pastor and Goate, 2004). In any patient with a strong family history of Alzheimer’s disease and onset prior to age 60 years, genetic testing should be considered.

What test would you order next?

Your colleagues who attended the Banner Alzheimer’s Institute Case Conference answered as follows:

| A. Repeat neuropsychological testing (modified to evaluate for malingering) | 70% |

| B. PET | 20% |

| C. Lumbar puncture (for amyloid and tau) | 10% |

| D. Genotyping | 0% |

| E. Electroencephalogram | 0% |

| F. No need for further testing | 0% |

IMPRESSION

At the conclusion of this first visit, the clinician’s impression was as follows. The patient is a 49-year-old female who presents for a cognitive evaluation. The clinical history and cognitive findings are consistent with a dementia. The most likely etiology of this dementia is Alzheimer’s disease, but atypical given the patient’s relatively young age. Frontotemporal dementia is also likely given the strong emotional component with significant depressive features and anxiety. Further testing will be required for diagnosis.

PLAN

At the conclusion of this first visit, the clinician’s plan was as follows:

- Order a PET scan of the brain to help distinguish between Alzheimer’s disease and frontotemporal dementia.

- If the PET scan does not give conclusive results, consider a lumbar puncture or genotyping in the future.

- At this time, hold off on dementia-specific medications but readdress this issue once the diagnosis is made.

- At this time, initiate citalopram to help treat the depression and anxiety. Start at 10 mg/d and increase to 20 mg after 1 week. The potential side effects of citalopram were discussed with the patient.

- Encourage the patient and her husband to meet with our nurse specialist and social worker for family psychotherapy. Issues to discuss are how to bring up the diagnosis with their 8-year-old daughter. Also, given that the patient is relatively young, there may be other social issues as well as financial issues to consider.

- The patient was instructed to stop driving.

- The possibility of clinical trial participation was briefly discussed with the patient and will be discussed in the future once the diagnosis has been made.

- The patient will return for a follow-up visit in approximately 6 weeks.

All attendees at the case conference agreed that this was a reasonable plan. Of note, the treating physician did not consider malingering in the differential diagnosis.

What do you predict will be the results of the FDG-PET scan?

Your colleagues who attended the Banner Alzheimer’s Institute Case Conference answered as follows:

| A. Inconclusive | 0% |

| B. Alzheimer’s disease | 50% |

| C. Frontotemporal dementia | 50% |

Official radiology report

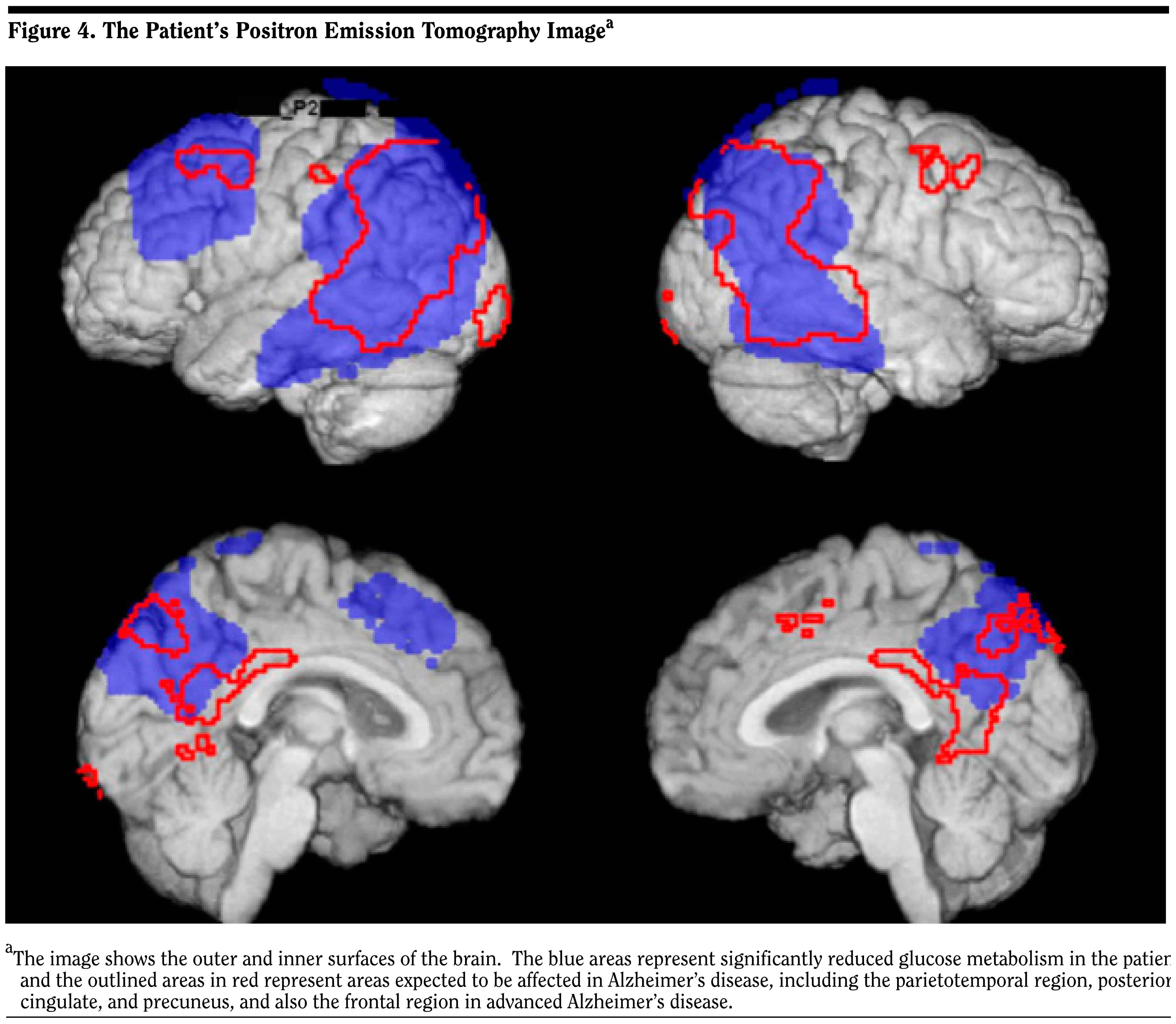

- Very extensive hypometabolism in both parietal and temporal lobes and in the left frontal lobe (Figure 4).

- The pattern favors Alzheimer’s type dementia, although clearly there is extensive involvement of the left frontal lobe.

Updates

A phone call was made to the patient’s husband to report the PET scan results and to give the diagnosis of Alzheimer’s disease. Although saddened by the diagnosis, he was relieved that a final diagnosis had been made. The patient and her husband have an appointment scheduled with Banner Alzheimer’s Institute’s Family and Community Services team. The patient’s husband reports that citalopram has significantly improved her overall mood; she is less tearful and anxious. At the next visit, the plan will be to initiate a cholinesterase inhibitor, and once stable, add memantine. We will also discuss the possibility of participation in clinical research.

Disclosure of Off-Label Usage

The authors have determined that, to the best of their knowledge, no investigational information about pharmaceutical agents that is outside US Food and Drug Administration–approved labeling has been presented in this article.

Financial Disclosure

Dr Yaari is a consultant for Amedisys Home Health. Dr Tariot is a consultant for Acadia, AC Immune, Allergan, Eisai, Epix, Forest, Genentech, MedAvante, Memory Pharmaceuticals, Myriad, Novartis, Sanofi-Aventis, Schering-Plough, and Worldwide Clinical Trials; has received consulting fees and grant/research support from Abbott, AstraZeneca, Avid, Baxter, Bristol-Myers Squibb, GlaxoSmithKline, Elan, Eli Lilly, Medivation, Merck, Pfizer, Toyama, and Wyeth; has received educational fees from Alzheimer’s Foundation of America; has received other research support only from Janssen and GE; has received other research support from National Institute on Aging, National Institute of Mental Health, Alzheimer’s Association, Arizona Department of Health Services, and Institute for Mental Health Research; is a stock shareholder in MedAvante and Adamas; and holds a patent for “Biomarkers of Alzheimer’s Disease.” Drs Fleisher, Burke, and Seward and Mss Brand and Dougherty have no personal affiliations or financial relationships withany commercial interest to disclose relative to the actvity.

Disclaimer

The opinions expressed are those of the authors, not of Banner Health or Physicians Postgraduate Press.

Clinical Points

- Early-onset Alzheimer’s disease can have atypical presentations, including having the appearance of psychiatric disturbance.

- FDG-PET scans are useful in distinguishing between Alzheimer’s disease and frontotemporal dementia.

- CSF studies for amyloid and tau proteins can also be useful tests for Alzheimer’s disease in clinically ambiguous cases.

- Patients with early-onset Alzheimer’s disease have different social and counseling needs than those with late-onset Alzheimer’s disease. For example, as seen in this case, they may need counseling on how to explain the disease to young children.

Find more articles on this and other psychiatry and CNS topics:

The Journal of Clinical Psychiatry

The Primary Care Companion for CNS Disorders

REFERENCES

American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fourth Edition, Text Revision (DSM-IV-TR). Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association; 2000.

Fagan AM, Head D, Shah AR, et al. Decreased cerebrospinal fluid Abeta(42) correlates with brain atrophy in cognitively normal elderly. Ann Neurol. 2009;65(2):176–183. PubMed doi:10.1002/ana.21559

Hampel H, Buerger K, Zinkowski R, et al. Measurement of phosphorylated tau epitopes in the differential diagnosis of Alzheimer disease: a comparative cerebrospinal fluid study. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2004;61(1):95–102. PubMed doi:10.1001/archpsyc.61.1.95

Hort J, O’ Brien JT, Gainotti G, et al; EFNS Scientist Panel on Dementia. EFNS guidelines for the diagnosis and management of Alzheimer’s disease. Eur J Neurol. 2010;17(10):1236–1248. PubMed doi:10.1111/j.1468-1331.2010.03040.x

Hu YY, He SS, Wang X, et al. Levels of nonphosphorylated and phosphorylated tau in cerebrospinal fluid of Alzheimer’s disease patients: an ultrasensitive bienzyme-substrate-recycle enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay. Am J Pathol. 2002;160(4):1269–1278. PubMed doi:10.1016/S0002-9440(10)62554-0

Knopman DS, DeKosky ST, Cummings JL, et al; Report of the Quality Standards Subcommittee of the American Academy of Neurology. Practice parameter: diagnosis of dementia (an evidence-based review). Neurology. 2001;56(9):1143–1153. PubMed

Links KA, Merims D, Binns MA, et al. Prevalence of primitive reflexes and parkinsonian signs in dementia. Can J Neurol Sci. 2010;37(5):601–607. PubMed

Maddalena A, Papassotiropoulos A, M×¼ller-Tillmanns B, et al. Biochemical diagnosis of Alzheimer disease by measuring the cerebrospinal fluid ratio of phosphorylated tau protein to beta-amyloid peptide42. Arch Neurol. 2003;60(9):1202–1206. PubMed doi:10.1001/archneur.60.9.1202

Mungas D. In-office mental status testing: a practical guide. Geriatrics. 1991;46(7):54–58, 63, 66. PubMed

Pastor P, Goate AM. Molecular genetics of Alzheimer’s disease. Curr Psychiatry Rep. 2004;6(2):125–133. PubMed doi:10.1007/s11920-004-0052-6

Schuff N, Woerner N, Boreta L, et al; Alzheimer’s Disease Neuroimaging Initiative. MRI of hippocampal volume loss in early Alzheimer’s disease in relation to ApoE genotype and biomarkers. Brain. 2009;132(4):1067–1077. PubMed doi:10.1093/brain/awp007

Shaw LM, Vanderstichele H, Knapik-Czajka M, et al; Alzheimer’s Disease Neuroimaging Initiative. Cerebrospinal fluid biomarker signature in Alzheimer’s disease neuroimaging initiative subjects. Ann Neurol. 2009;65(4):403–413. PubMed doi:10.1002/ana.21610

Thal LJ, Kantarci K, Reiman EM, et al. The role of biomarkers in clinical trials for Alzheimer disease. Alzheimer Dis Assoc Disord. 2006;20(1):6–15. PubMed doi:10.1097/01.wad.0000191420.61260.a8

Enjoy this premium PDF as part of your membership benefits!