Abstract

Aripiprazole is a second-generation partial dopamine D₂ receptor agonist antipsychotic approved for the treatment of schizophrenia and maintenance treatment of bipolar I disorder. As the only partial dopamine D₂ receptor agonist available in both oral and long-acting injectable (LAI) formulations, it provides flexibility for tailoring treatment across different phases of the illness. Two LAI formulations of aripiprazole monohydrate are available: aripiprazole once-monthly 400 mg and aripiprazole 2-month ready-to-use 960 mg, offering options to accommodate patient needs and preferences and support adherence. The aripiprazole monohydrate LAIs are well-supported options for early intervention and maintenance treatment, with evidence demonstrating clinical effectiveness in reducing relapse and hospitalizations while supporting enhanced adherence. LAI antipsychotics, including aripiprazole monohydrate, offer practical benefits for patients with schizophrenia, particularly those at risk for nonadherence or recurrent episodes. However, these formulations are often underutilized due to lingering stigma and misperceptions, leading many clinicians to defer use of these agents until later in the treatment course. To support earlier and more informed use of aripiprazole monohydrate LAIs, a panel of psychiatric experts convened to review the latest evidence and share clinical strategies for integrating this agent into a comprehensive treatment plan. This Academic Highlights section presents the main points of their consensus recommendations, offering practical guidance for prescribers seeking to optimize outcomes in patients with schizophrenia.

J Clin Psychiatry 2025;86(3):plunlai2424ah2

Published Online: August 13, 2025.

To Cite: Correll CU, Achtyes ED, Sajatovic M, et al. Clinical application of aripiprazole monohydrate long-acting injectables for the treatment of schizophrenia: a consensus panel report. J Clin Psychiatry. 2025;86(3):plunlai2424ah2.

To Share: https://doi.org/10.4088/JCP.plunlai2424ah2

© 2025 Physicians Postgraduate Press, Inc.

See more Academic Highlights in this series: Part 1 | Part 3

This Academic Highlights section of The Journal of Clinical Psychiatry presents the highlights of the virtual consensus panel meeting “Clinical Application of Aripiprazole Monohydrate Long-Acting Injectables for the Treatment of Schizophrenia: A Consensus Panel Report,” which was held September 9, 2024.

The meeting was chaired by Joseph F. Goldberg, MD, Department of Psychiatry, Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai, New York, New York. The faculty were Eric D. Achtyes, MD, MS, Department of Psychiatry, Western Michigan University Homer Stryker M.D. School of Medicine, Kalamazoo, Michigan; Christoph U. Correll, MD, Department of Psychiatry, Zucker Hillside Hospital, Glen Oaks, New York; Department of Psychiatry and Molecular Medicine, Donald and Barbara Zucker School of Medicine at Hofstra/ Northwell, Hempstead, New York; Department of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry, Charité Universitätsmedizin, Berlin, Germany; German Center for Mental Health (DZPG), partner site Berlin, Berlin, Germany; Martha Sajatovic, MD, Department of Psychiatry and Department of Neurology, Case Western Reserve University School of Medicine, Cleveland, Ohio; and Stephen R. Saklad, PharmD, BCPP, Division of Pharmacotherapy, College of Pharmacy, The University of Texas at Austin, San Antonio, Texas.

Financial disclosures appear at the end of the article.

This evidence-based peer-reviewed Academic Highlights was prepared by Healthcare Global Village, Inc. The panel meeting for the development of this article was funded by Otsuka Pharmaceutical Europe Ltd and H. Lundbeck A/S. Both companies also funded article processing charges, medical writing, editorial, and other assistance. Editorial support was provided by Therese Castrogiovanni, PharmD, BCACP, CDCES, Banner Medical LLC, and Healthcare Global Village with funding by Otsuka Pharmaceuticals Europe Ltd & H. Lundbeck A/S. The sponsors performed a courtesy review for medical accuracy. The opinions expressed herein are those of the faculty and do not necessarily reflect the views of Healthcare Global Village, Inc., the publisher, or the commercial supporters. This article is distributed by Otsuka Pharmaceutical Europe Ltd and H. Lundbeck A/S for educational purposes only.

Schizophrenia is a severe neuroprogressive mental disorder characterized by high relapse rates, with most patients experiencing multiple relapses after recovering from a first psychotic episode.1,2 These relapse episodes hold potentially serious consequences, including loss of autonomy, diminished employment and educational opportunities, the risk of harm to oneself or others, disruption of personal relationships, and increased stigmatization.3,4 In addition to these psychosocial consequences, there is compelling evidence of biological harm, as some previously responsive patients may develop treatment resistance following each subsequent relapse episode, a phenomenon referred to as neurotoxicity or “neuroprogression.”5 Despite the availability of numerous pharmacological options for schizophrenia, poor adherence to prescribed antipsychotic medication is a major contributor to relapse, as impaired insight and cognitive dysfunction can interfere with a patient’s ability to maintain consistent medication use.6 Indeed, treatment nonadherence has been consistently identified as the strongest predictor of relapse and poor illness outcomes,7 with studies showing that patients who discontinue medication are 2 to 5 times more likely to relapse compared to those who maintain adherence with their medication regimen.3,5,8

Due to the vast array of potential presenting symptoms, treatment of schizophrenia is complex and requires a comprehensive care plan integrating psychosocial interventions with effective pharmacological treatment.9,10 Long-acting injectable (LAI) formulations of second-generation antipsychotics, such as aripiprazole, olanzapine, paliperidone, and risperidone, offer a promising strategy to mitigate nonadherence by reducing the frequency of dosing and ensuring consistent drug delivery over an extended period.11,12 As a result, LAIs have been associated with lower relapse rates and improved clinical outcomes in patients diagnosed with schizophrenia, underscoring their clinical utility in preventing exacerbations and maintaining long-term stability.13 Although LAI antipsychotic medications have generally been viewed as options to be tried only after failure of multiple oral medications, they have demonstrated favorable tolerability and consistent efficacy both in treating both acute episodes and in the maintenance phase of schizophrenia,13,14 warranting consideration of their use earlier in the schizophrenia treatment algorithm.15–20 Compared with oral medications, LAIs are associated with increased medication adherence, prolonged time to first hospitalization, improved patient functionality, and reduced mortality and may be more beneficial when given earlier rather than later in the course of the disease.21–28 LAIs are also associated with improved disease insight, which can be beneficial for many patients with schizophrenia as lack of insight is a driver of medication nonadherence.29,30

Aripiprazole is a second-generation partial dopamine D₂ receptor agonist antipsychotic, which is available as an LAI in 2 different molecular versions, aripiprazole monohydrate and aripiprazole lauroxil, a prodrug of aripiprazole that we will not cover in this review, as it has been reviewed comprehensively very recently.31 Aripiprazole monohydrate is available in 2 different LAI formulations, aripiprazole once-monthly 400 mg (AOM 400), which is an extended-release LAI formulation of aripiprazole monohydrate for administration every 28 days via deltoid or gluteal intramuscular injection, and aripiprazole 2-month ready-to-use 960 mg (Ari 2MRTU 960), which is the newest LAI formulation approved containing 960 mg of aripiprazole monohydrate that is administered by gluteal injection once every 2 months. Both formulations are approved in the US, Europe, and Canada for the treatment of schizophrenia in adults.32–36 In the US and Canada, the aripiprazole monohydrate LAIs are also indicated for maintenance monotherapy treatment of bipolar I disorder in adults.32–36 Among available LAI antipsychotics, aripiprazole is differentiated by its dopamine partial agonism.37 Aripiprazole exhibits a high affinity for both dopamine and serotonin receptors, acting as a partial D2, D3, and 5-HT1A agonist, as well as a 5-HT2A antagonist.38

In a recent consensus panel meeting, a group of psychiatric experts was convened to evaluate the clinical utility of LAI antipsychotics, with a focus on aripiprazole monohydrate, as a viable treatment option for patients diagnosed with schizophrenia that can be administered early in the course of the disease. The panel reviewed the pharmacological advantages associated with partial dopamine agonists, the potential benefits of initiating LAI treatment early in the disease course, and the common misperceptions that contribute to underutilization of these formulations. Additional discussions addressed the role of non-prescribing healthcare professionals, the importance of patient-centered care, systemic barriers to access, and the need to prioritize holistic and functional recovery. This Academic Highlights article provides a summary of the panel’s discussion and presents their key conclusions.

Methods

In October 2024, a panel of experts in psychopharmacology, the clinical treatment of schizophrenia, and antipsychotic prescribing convened to develop clinical recommendations on the use of aripiprazole monohydrate LAIs for adults diagnosed with schizophrenia. The panel was chaired by Joseph F. Goldberg, MD, and included panelists Eric D. Achtyes, MD, Christoph U. Correll, MD, Martha Sajatovic, MD, and Stephen R. Saklad, PharmD. The consensus panel meeting was held virtually with facilitated discussion. The panel analyzed publicly available clinical trial data and shared their perspectives to reach a consensus on utilization of aripiprazole monohydrate LAIs in treatment considerations for schizophrenia. This article presents the consensus findings from the panel discussion.

Aripiprazole Monohydrate Long-Acting Injectable: Myths and Misperceptions

Antipsychotics remain the cornerstone of schizophrenia treatment, with first-generation antipsychotics (FGAs), such as haloperidol and chlorpromazine, historically serving as the primary therapeutic agents.39 These antipsychotics exert their effects through potent dopamine D2 receptor antagonism, effectively reducing positive symptoms, such as hallucinations and delusions.40 However, FGAs are associated with a high incidence of extrapyramidal symptoms (EPS), including drug-induced parkinsonism (DIP), dystonia, akathisia, and tardive dyskinesia, as well as limited efficacy in treating negative and cognitive symptoms.41 These limitations led to the development of second-generation antipsychotics (SGAs), which retain D2 receptor antagonism but incorporate additional serotonergic activity, particularly 5-HT2A antagonism. This broader pharmacologic profile is believed to reduce EPS and provide greater efficacy across multiple symptom domains.41,42 Despite these therapeutic advances, SGAs introduced new safety concerns, most notably increased risks of cardiometabolic side effects such as weight gain, insulin resistance, and dyslipidemia, which can negatively affect long-term health and treatment adherence.14,41,43–45 Consequently, the use of SGAs requires individualized risk-benefit assessment and ongoing monitoring.46,47

To further address the persistent challenge of nonadherence, long-acting injectable (LAI) formulations of antipsychotics were introduced over 50 years ago to extend dosing intervals and reduce the need for daily oral medication. Although FGA LAIs offered the potential for improved adherence and clinical outcomes, their initial reception was mixed. Both clinicians and patients expressed concerns about increased adverse effects, questionable efficacy, and a perception that LAIs compromised patient autonomy by enforcing treatment.41,42,48 Moreover, FGA LAIs were typically formulated in oil-based vehicles, which were associated with a higher incidence of injection site adverse events. The development of SGA LAIs aimed to overcome many of these challenges by offering improved tolerability, reduced EPS, and greater efficacy. Importantly, SGA LAIs use aqueous or polymer-based vehicles,49 which are associated with fewer injection site reactions, further enhancing their acceptability and potential to support sustained treatment adherence.14,42,50

There are currently 10 LAI antipsychotics approved in the US for the treatment of schizophrenia, offering clinicians multiple options for tailoring therapy to patient needs.51 Notably, aripiprazole is the only partial dopamine agonist available in LAI formulation, combining dopaminergic and serotonergic modulation with the adherence benefits of extended-release delivery.52,53

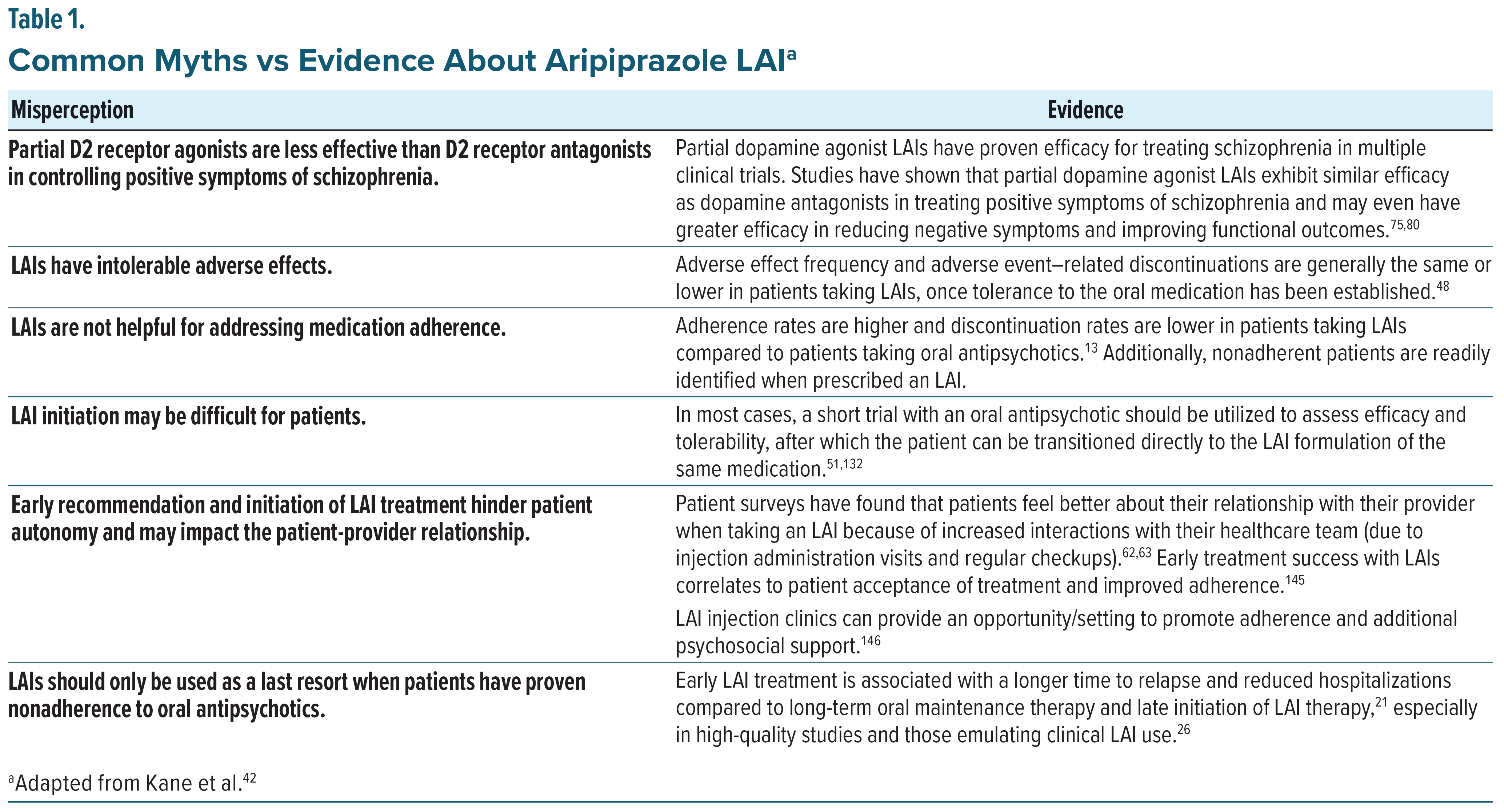

Despite their advantages over oral therapies, LAI antipsychotics are underutilized; fewer than 20% of patients diagnosed with schizophrenia have been prescribed LAIs worldwide.54,55 Patient and clinician perceptions, including a lack of familiarity, perceived additional workload, and stigma, contribute to the relegation of LAIs as nonpreferred treatment options.56 One survey, which included mental health nurses and physicians, found that three-fourths of physicians did not utilize LAIs as an early treatment option, even if they were aware of the clinical benefits of LAI antipsychotics. The most commonly cited reason by physicians for delaying LAI use was concerns about patient perception of LAIs.42,57 Common patient concerns about LAI antipsychotic use include having to go to the clinic frequently for injections, lack of autonomy in medication administration, and stigma related to the perception that injectable antipsychotics are for patients with severe mental disorders.42,56 Beyond barriers to LAI use, misunderstandings regarding partial agonist pharmacology and aripiprazole’s mechanism of action may also contribute to underuse of the LAI formulations of aripiprazole (Table 1). Expanding clinician understanding of the aripiprazole monohydrate LAI mechanism of action, efficacy, and safety profile will allow prescribers to better facilitate conversations with patients and their caregivers about its early use as an effective and well-tolerated treatment for schizophrenia.

Overcoming Barriers to LAI Treatment

Because LAI antipsychotic medications require administration by a healthcare professional, access to care may be limited in some areas. Transportation to a healthcare site may be a barrier due to a lack of personal or public transportation or a lack of a facility near the patient’s home. Leveraging non-physician healthcare providers, such as nurses and pharmacists, to administer these injections creates more opportunities to access care and helps reduce or eliminate this barrier. Currently, almost all states in the US allow pharmacists to administer LAI antipsychotic medications, expanding LAI treatment access and convenience.58 As a result, studies have shown that when pharmacists administer LAI antipsychotic medications it positively improves medication adherence and patient satisfaction.59

Stigma is an additional barrier that can play a role in LAI antipsychotic underutilization. A survey of 350 psychiatrists found that less than 36% of the providers’ patients had been offered an LAI antipsychotic due to physician concerns about efficacy, adverse events, and medication cost.19 Additional surveys have found that patients may be hesitant about loss of autonomy with LAI antipsychotic use as well as injection site pain, both of which are concerns that can be improved through a patient-centered discussion with a healthcare provider.60 Of note, the recently published INTEGRATE international guidelines for the algorithmic treatment of schizophrenia61 state that “the initial choice of antipsychotic should be made collaboratively with the patient and based on the side effect and efficacy profile. Dose scheduling, convenience, and the availability of a long-acting formulation of medication might also be factors to consider.” Consistent with these guidelines, data indicated that when patients are fully informed about LAI therapy, it often becomes the patient’s preference. A survey of French patients who had taken multiple dosage forms of antipsychotics found that LAIs were the patients’ preferred dosage form, with interviewees reporting that they felt LAIs were more effective than other forms of medication and that they felt more supported in their illness through increased contact with their comprehensive care team. In the same survey, 49% of patients reported that LAI therapy could positively impact their future plans, particularly in finding a stable job.62 Additional studies have shown that when presented with information about multiple hypothetical antipsychotic medication formulations, both patients and providers generally demonstrated a preference for LAIs over oral treatment.63 The use of LAI drug formulation is not unique to psychiatry; similar formulations are employed in other areas of medicine, such as HIV treatment, low-density lipoprotein cholesterol treatment, diabetes management, and hormonal contraception, and have been demonstrated to improve adherence and clinical outcomes. These examples may help normalize the use of LAIs in mental health by framing them as part of a broader movement toward patient-centered, long-acting pharmacotherapy. Because the majority of patients in study samples will try LAI antipsychotic therapy when the option is fully explained and offered early in disease progression, there is a need to address stigma through provider and patient education and shared decision-making.64,65

Panel Consensus Statement #1

Reducing Stigma and Barriers: “Addressing stigma associated with LAIs is crucial. Leveraging the entire healthcare team surrounding the patient is likewise imperative for optimal results. The panel advocates for reframing LAIs as a viable first-line option rather than a punitive, last-resort measure, thus encouraging patient and clinician consideration and choice.”

Aripiprazole Monohydrate: Mechanism and Medication Profile

The multiple symptom domains of schizophrenia present a significant challenge in adequately treating schizophrenia. First-generation antipsychotics primarily target positive symptoms, while negative and cognitive symptoms have remained elusive to control and may even worsen with FGAs. Even low levels of negative symptoms are correlated with difficulties in aspects of everyday functioning and are closely linked with functional decline in patients living with schizophrenia.66,67 Dopamine receptor partial agonists, such as aripiprazole, have proven to be effective in controlling multiple symptom domains in schizophrenia, including both positive and negative symptoms,68–70 offering patients and providers the potential for better symptom control with a single medication.71

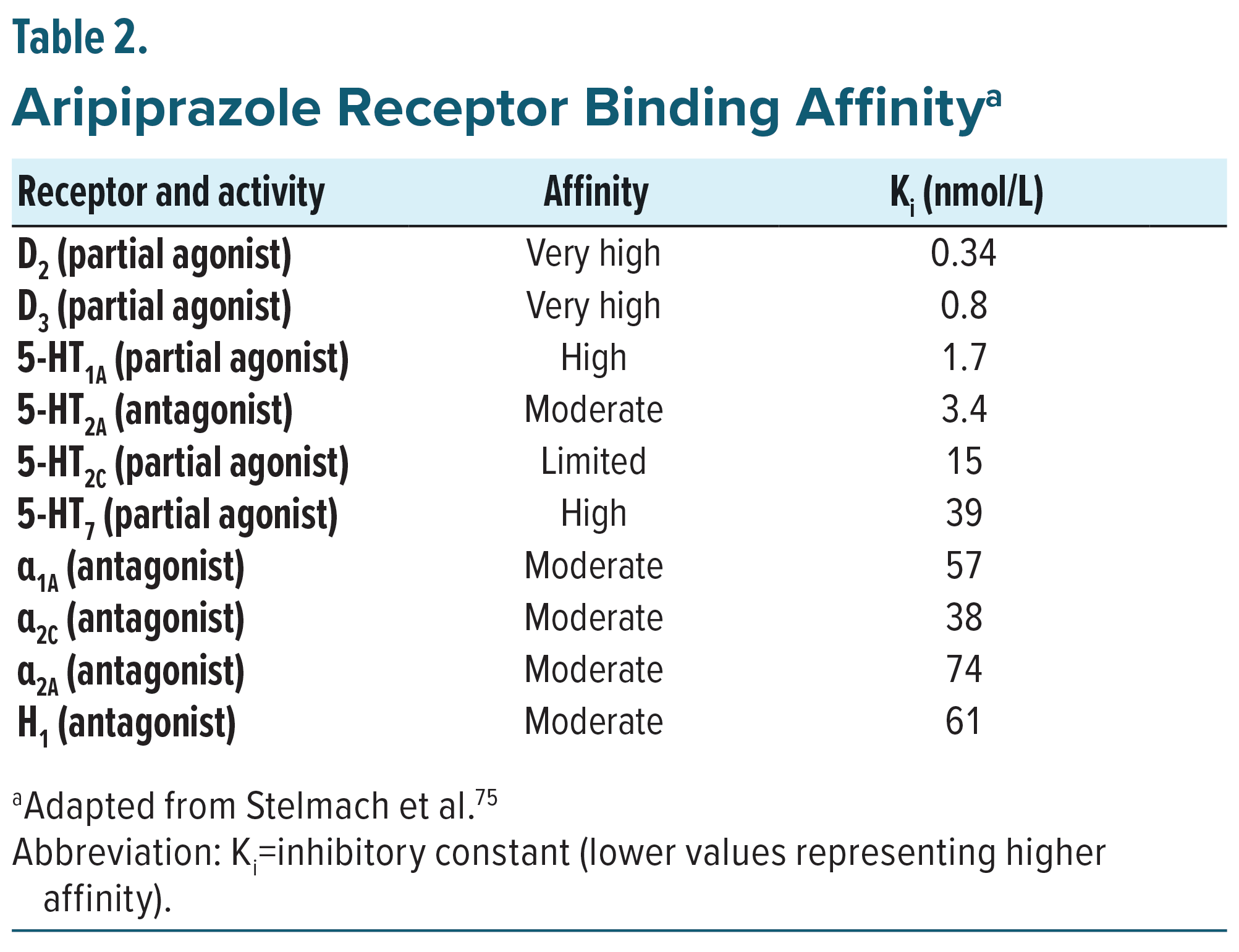

Aripiprazole has a multifaceted pharmacological mechanism, most notably via partial agonist activity at dopaminergic D2 and D3 and serotonergic 5-HT1A receptors and antagonist activity at serotonergic 5-HT2A receptors. Aripiprazole exhibits a higher affinity for the D2 and D3 receptors than for the serotonin receptors, so its proposed mechanism of action is predominantly a dopamine-system stabilizer (Table 2).52,72 Aripiprazole’s partial agonist activity allows it to bind to D2 and D3 receptors with a higher affinity than endogenous dopamine, therefore blocking dopamine from activating the receptors and modulating dopamine neurotransmission in the mesolimbic, striatal, and mesocortical pathways. It is hypothesized that positive symptoms of schizophrenia are related to hyperdopaminergic transmission in the striatal brain regions,73,74 while cognitive and negative symptoms stem from impairment of dopamine transmission in the mesocortical and mesolimbic pathway, so modulating dopamine transmission in these areas may help mitigate positive, as well as negative, and cognitive symptoms of schizophrenia.75,45,71

Aripiprazole’s special pharmacological profile allows it to be an effective treatment for schizophrenia with a lower risk of concerning adverse effects when compared with many other antipsychotics. First-generation D2 dopamine receptor antagonism results in a dose-dependent blockade of most to all dopamine mediated neurotransmission, which is associated with significant adverse effects, such as extrapyramidal symptoms (EPS), including akathisia and tardive dyskinesia.41,76,77 Strong dopamine D2 receptor antagonism may also cause dose-related elevations in prolactin levels, which are associated with infertility, osteoporosis, decreased libido, dysmenorrhea, galactorrhea, gynecomastia, and erectile dysfunction.68,78 Aripiprazole’s partial agonism at dopamine receptors regulates dopamine receptor-mediated neurotransmission, resulting in a lower risk of EPS and hyperprolactinemia than with most other antipsychotics. Additionally, due to aripiprazole’s low affinity for histamine and muscarinic receptors, aripiprazole carries a lower risk of cardiometabolic adverse effects than most other second-generation antipsychotics.43–45,68,78

Efficacy of Aripiprazole Monohydrate LAIs for Schizophrenia

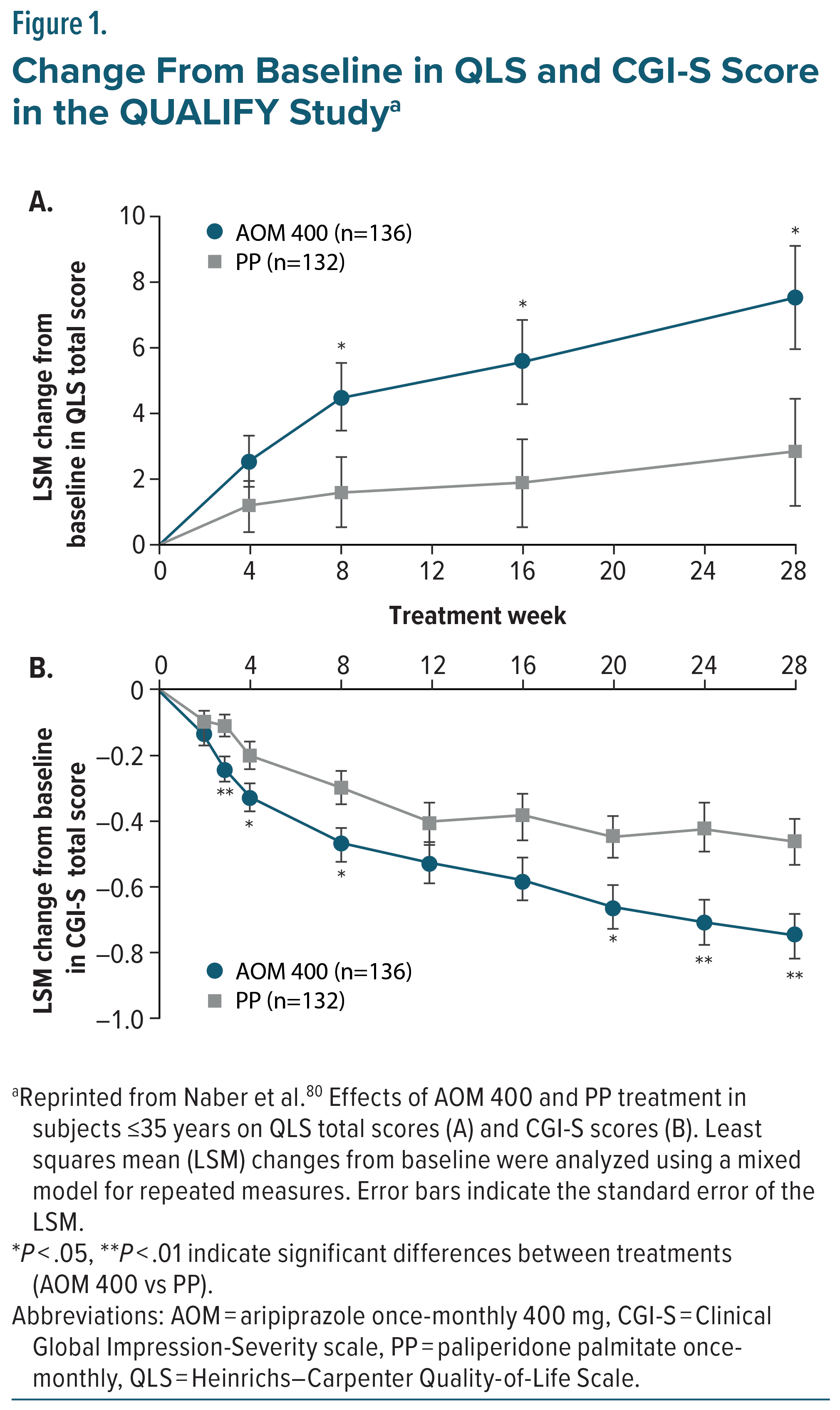

Aripiprazole monohydrate LAIs have been rigorously studied for the treatment of schizophrenia. Efficacy was initially established for AOM 400 in a double-blind, placebo-controlled, 52-week trial, which evaluated the safety and efficacy of AOM 400 compared to placebo in patients with schizophrenia. The study found that treatment with AOM 400 significantly delayed the time to relapse in both the interim and final analyses (P < .0001) and demonstrated overall lower relapse rates than placebo (10.0% compared to 36.9%, respectively).79 Due to the demonstrated efficacy of AOM 400 at interim analysis, the trial was terminated early, and its results supported the FDA approval of AOM 400 as a treatment for schizophrenia.79 A subsequent 38-week double-blind, active controlled, study compared AOM 400 to oral aripiprazole (10 – 30 mg) over 38 weeks in patients with schizophrenia. AOM 400 was demonstrated to be non-inferior to oral aripiprazole in the Kaplan-Meier estimated impending relapse rates at week 26 (7.12% for AOM 400 and 7.76% for oral aripiprazole), the study’s predefined primary efficacy endpoint. Adverse events were similar between the two groups, and no new safety findings were reported.53 AOM 400 was also found to be non-inferior to oral aripiprazole in the secondary efficacy measure, time to all-cause discontinuation.53 The QUAlity of Life with AbiliFY Maintena (QUALIFY) study compared AOM 400 to paliperidone palmitate once-monthly (PP1M) in patients diagnosed with schizophrenia, utilizing improvement in the Heinrichs-Carpenter Quality of Life Scale (QLS) as a primary endpoint. Participants in a pre-defined subgroup ≤35 years old taking AOM 400 revealed significant improvement in QLS total score compared to those taking PP1M, with improvement becoming significant at 8 weeks of treatment and continuing through follow-up at week 28 (Figure 1A). Additionally, Clinical Global Impression-Severity (CGI-S) scores were assessed as a secondary endpoint, with the AOM 400 treatment group demonstrating significantly reduced scores compared to the PP1M treatment group, with the difference becoming significant at week 3 with continued divergence from PP1M through to the end of the study (Figure 1B).80

In a naturalistic, open-label, mirror-image study conducted in North America, patients diagnosed with schizophrenia who were taking oral antipsychotics were switched to AOM 400 and followed prospectively for 6 months. Hospitalization data from the 6 months prior to screening were collected retrospectively and compared with hospitalization rates during the prospective period. The primary analysis compared psychiatric hospitalization rates in the 3 months before switching to the 3 months after. Hospitalization was significantly reduced, with only 2.7% of patients hospitalized during the 3 months on AOM 400 compared to 27.1% in the 3 months prior while on oral antipsychotics (P < .0001). A secondary analysis comparing the full 6-month periods before and after the switch also showed a substantial reduction in hospitalizations (8.8% vs. 38.1%,P.< .0001).81

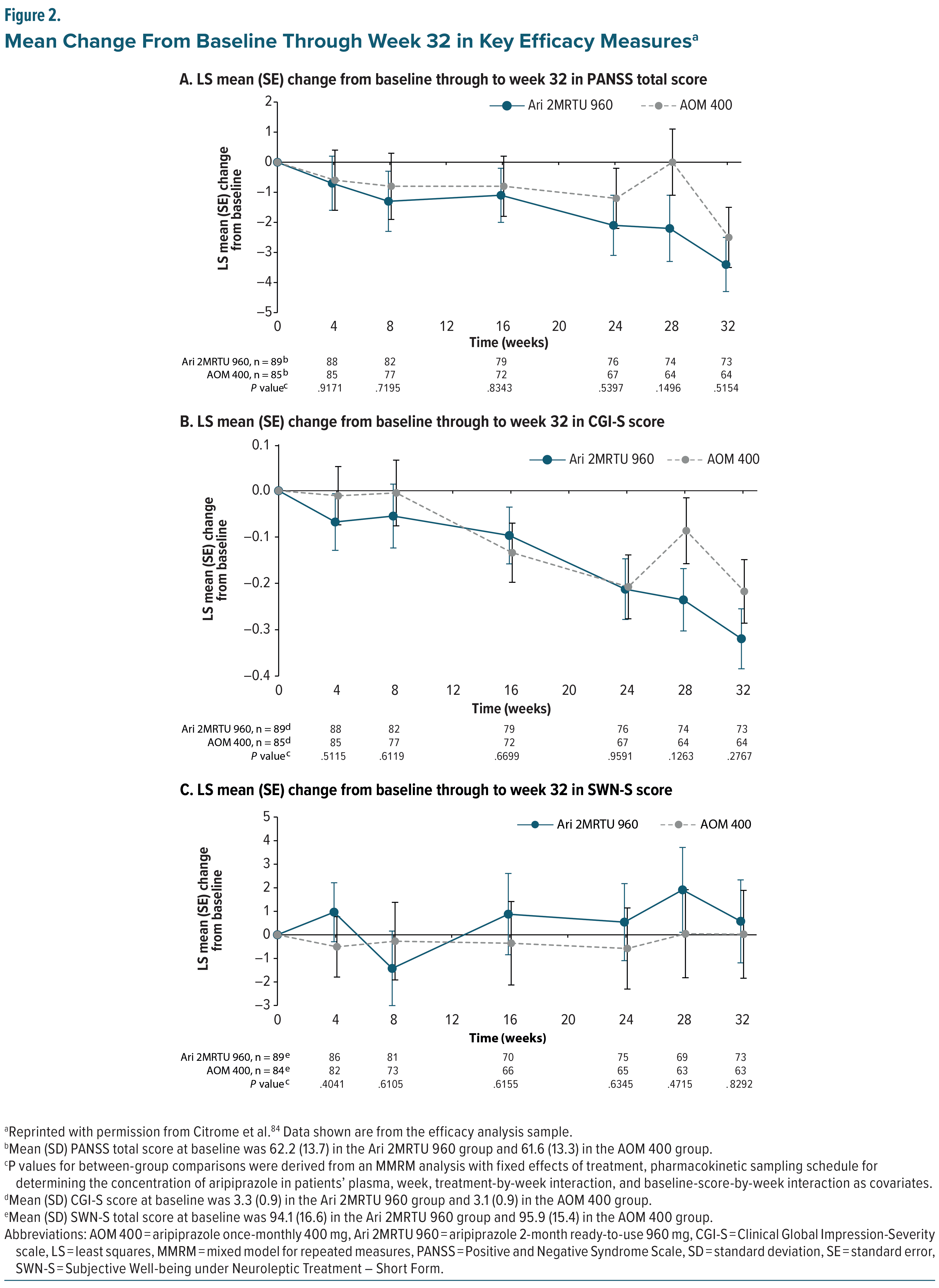

The most recently developed aripiprazole monohydrate LAI, Ari 2MRTU 960, was approved based on a 32-week, open-label, bridging noninferiority study, which primarily evaluated its pharmacokinetics, safety, and tolerability and secondarily assessed its additional pharmacokinetic parameters and clinical efficacy compared with AOM 400 in clinically stable patients diagnosed with schizophrenia or bipolar I disorder. Ari 2MRTU 960 was designed to ensure that plasma concentrations remained similar and comparable to AOM 400 plasma concentrations after multiple doses.82 It was shown that following 4 administrations, Ari 2MRTU 960 delivered mean aripiprazole plasma concentrations that remained above the minimum therapeutic concentration of aripiprazole over the full 2-month dosing interval.36,83 In a secondary analysis that included only patients diagnosed with schizophrenia, the Positive and Negative Syndrome Scale (PANSS) score, CGI-S score, and Subjective Well-being under Neuroleptic Treatment–Short Form (SWN-S) score were monitored and found to be similar between the two treatment groups, with subjects remaining clinically stable throughout the course of the study (Figure 2).84

Safety of Aripiprazole Monohydrate LAIs

While antipsychotic medication efficacy is vital to treatment success, adverse events from antipsychotic medication are also significant factors in patient quality of life and medication adherence.85 One study found that most adverse events associated with antipsychotic medications, including EPS, cognitive adverse events, prolactin or endocrine-related effects, and cardiometabolic effects, significantly reduced the likelihood of adherence.86 Therefore, prescribing a medication with a favorable tolerability profile is critical to allow patients the best chance to stay on antipsychotic treatment long-term. Aripiprazole monohydrate LAIs provide an effective treatment option with relatively minimal potential adverse events.

The safety profile of aripiprazole monohydrate LAIs has been established in numerous controlled trials against placebo, oral aripiprazole, and other LAI antipsychotics. In a large placebo-controlled trial, AOM demonstrated low levels of EPS symptoms, metabolic disturbances, and weight gain.79 When compared to oral aripiprazole, patients taking AOM experienced similar rates of metabolic changes, weight gain, and EPS symptoms.53 In the previously described QUALIFY study, patients receiving AOM were less likely to report increased weight, psychotic disorder, and insomnia than patients assigned to take PP1M, with a low incidence of EPS symptoms observed in both groups. Further, clinically significant weight gain, defined as an increase ≥7% from baseline were similar, but numerically lower for AOM 400 than PP1M, reported in 11.1% and 14.6% of trial participants, respectively.80 Further, in an open-label, multiple-dose, randomized, parallel-arm, multicenter trial comparing AOM 400 with Ari 2MRTU 960 in patients diagnosed with schizophrenia, the incidence of treatment-related and serious adverse events was similar between AOM 400 and Ari 2MRTU 960, with increased weight, mild and transient injection site pain, akathisia, and insomnia as the most frequently reported adverse events for both dosage forms. All adverse events were consistent with the previously reported safety profile, and there were no discontinuations due to adverse events.84 The majority of adverse events in either treatment group were mild to moderate in nature and occurred following the first injection, with a lower incidence of adverse events reported with subsequent injections of either AOM 400 or Ari 2MRTU 960.

Clinical Application of Aripiprazole Monohydrate LAIs for Schizophrenia Treatment

A vital component of schizophrenia treatment is medication adherence, as it is critical for symptom stability and relapse prevention. Rates of nonadherence in serious mental illnesses, including schizophrenia, can be as high as 40%-50%.87,88 The consequences of nonadherence are severe; medication nonadherence may result in hospitalization following treatment gaps as short as 1–10 days due to breakthrough symptoms, which can lead to relapse, requiring acute medical care.89 Medication nonadherence has also been associated with emergency services usage, poor social and occupational functioning, violence, arrests, increased suicide risk, lower quality of life, and treatment resistance.29,90 Additionally, gaps in treatment due to medication nonadherence have been reported to be associated with longer durations of relapse, which are associated with a significant decrease in total brain, frontal lobe, and white matter volumes.91

A systematic review by Velligan and colleagues identified 11 categories for medication nonadherence in serious mental illnesses. These included poor disease insight, negative attitude toward taking prescribed medications, distressing medication adverse effects, poor therapeutic alliance, stigma, substance abuse, cognitive impairment, depression, lack of family/social support, limited access to mental health care, and poor social functioning. Intentional nonadherence due to reduced disease insight was a significant factor in medication nonadherence in 55.6% of the studies analyzed.29 A separate meta-analysis and systematic review confirmed these findings, reporting that patient lack of insight into their disease was a common factor associated with medication nonadherence in multiple studies.87

Early intervention with LAIs can improve medication adherence and patient insight, thereby preventing relapses and possibly reducing neuroprogression associated with multiple episodes of psychosis.92–95 A study evaluating patients taking LAI risperidone for 50 weeks found that 26.4% of patients experienced a significant improvement in PANSS insight scores from “impaired” at baseline to “normal” or “near normal” by the end of the trial period. Patients who experienced improvement in insight scores also demonstrated improvement in negative symptoms, anxiety/depression, and overall quality of life.16 Patients experiencing their first episode of psychosis are most likely to stop medications,15 generally due to a lack of disease insight, which again highlights the utility of early intervention with an effective treatment regimen. The increased adherence associated with LAIs is likely the driver of improvements in patient insight and can be a useful strategy to keep patients engaged with their prescribing practitioner and healthcare team.15

In a retrospective study evaluating strategies for initiating LAI antipsychotics, patients who received an LAI proactively, before demonstrating nonadherence to oral medications or requiring emergency department (ED) visits or hospitalization due to relapse, experienced more favorable outcomes.96 These included reduced rates of hospital admissions, shorter lengths of stay, and fewer ED visits. In contrast, patients who were initiated on an LAI only after signs of nonadherence, or following an ED visit or hospitalization, demonstrated poorer outcomes across these same measures. The poorest outcomes were observed in patients who received an LAI only after experiencing multiple episodes of psychosis. These findings support the clinical value of early intervention with LAI treatment as a preferred strategy in the management of schizophrenia.96 Further, functional recovery, by early use of LAIs, is an important treatment goal in first episode and early phase patients.97 A 2019 meta-analysis found that SGA LAIs were significantly better at improving psychosocial function, in short or long-term trials, compared to placebo or oral antipsychotics.98 Early intervention has also been shown to increase employment and independent living and decrease disability and hospital admissions when compared with patients taking oral antipsychotic therapy.11,99 Additionally, in a nationwide Swedish database study, the risk of work disability was lower during use versus nonuse of any antipsychotic, but the lowest risk was observed for LAI antipsychotics, followed by oral aripiprazole and oral olanzapine. Adjusted hazard ratios were similar for early illness periods of <2 years, 2–5 years, and later illness periods of >5 years since diagnosis.100 Due to these benefits and the real-world challenges related to oral antipsychotic treatment, especially in terms of adherence, LAI antipsychotic medications may be a more prudent choice than oral therapies. This benefit of LAIs is greatest when offered proactively prior to evidence of nonadherence and the downstream complications that occur with relapse.96,101

In addition to improved patient outcomes, there is a significant economic impact associated with LAI use, including potential cost savings from reduced hospitalizations and lower healthcare utilization. LAI treatment can provide functional stability and reduce the need for frequent physician visits while facilitating more comprehensive care. In particular, LAI use in conjunction with psychosocial support may translate to cost savings by preventing severe relapses and preserving patient independence and productivity.20,102

Based on this evidence, the expert panel recommended a tiered approach to treating schizophrenia, favoring early use of LAIs. The panel recommended psychosocial treatments without pharmacotherapy in the prodromal phase of the disorder due to nonspecific symptoms and low conversion rates to psychosis.103,104 When considering patients for whom pharmacotherapy is indicated, the panel recommended LAIs to be considered after the first episode of psychosis in conjunction with psychosocial treatments over starting an LAI after multiple relapses have occurred due to improved medication adherence, evidence of increased patient insight, reduced relapse recurrence, improved functional outcomes, and reduced mortality risk in patients treated with LAIs.21,25,96,105–107

Current practice guidelines from the American Psychiatric Association (APA)108 and other international organizations109 on the treatment of patients diagnosed with schizophrenia recommend that medication selection should be guided by shared decision-making and involve a discussion about targeted symptoms, potential medication adverse effects, and patient-specific risk factors.110,111 Discussions should also include caregivers, such as family members, partners, or other significant individuals, when possible.112,113 A recent qualitative interview study showed that treatment selection of a specific LAI should acknowledge individual patient and caregiver preferences regarding formulation and frequency, to ensure that targeted disease management goals are met.114 The same study showed that patients, caregivers, and prescribers expressed overall positive views and general acceptance of an LAI administered once every 2 months for the treatment of schizophrenia given the perceived advantages of greater freedom and less treatment burden.114 The 2020 APA guideline update highlights that LAI antipsychotics should be utilized when preferred by the patient and when clinically appropriate based on available evidence.109, 115 One way to apply the LAI treatment paradigm in usual care settings is the GAIN approach, which consists of four steps (Goal setting, Action planning, Initiating treatment, and Nurturing motivation) to provide a structured conversation regarding LAI antipsychotic treatments, which can be utilized to gauge interest in eligible candidates for LAI antipsychotic therapy.116 These recommendations underscore the importance of discussing LAI antipsychotics with patients and utilization of LAIs early in the disease progression.117,118

Despite the incorporation of LAIs into these guidelines, the expert panel highlighted the need for clearer, evidence-based guidelines that prioritize LAIs in the schizophrenia treatment algorithm. The panel highlighted potential gaps in evidence related to the sequencing of antipsychotic therapies, particularly for patients who fail initial antipsychotic treatment. The expert panel discussed a recent meta-analysis that reviewed 11 randomized controlled trials assessing LAI efficacy for preventing hospitalization and relapse in patients with first-episode or early-phase schizophrenia. While the meta-analysis concluded that LAIs were not more effective than oral antipsychotics in preventing relapse or hospitalization, the expert panel noted that in 9 subgroup analyses that had a more pragmatic design or use of LAIs or had high-quality ratings, LAI treatment showed superior efficacy compared to oral antipsychotic therapy in patients with first-episode or early-phase schizophrenia.26 As these designs are more applicable in the real-world setting, the expert panel concluded that the breakdown of these sub-analyses offers credence for LAI efficacy over oral medications even early in the illness phase in clinical practice where LAIs are still used too sparsely. The panel also reviewed the open-label European Long-Acting Antipsychotics in Schizophrenia Trial (EULAST), evaluating the effects of paliperidone LAI, aripiprazole monohydrate LAI, oral paliperidone, and oral aripiprazole on medication adherence in patients with early-phase schizophrenia.119 Although the study found no difference in medication adherence between LAI and oral antipsychotics, the expert panel noted that the study results were affected by adherence bias because patients are more likely to take their oral medication when adherence is being actively monitored in a controlled clinical trial.120 Even more importantly, the study randomized patients from the start to the oral or LAI formulation of aripiprazole or paliperidone, instead of randomizing patients who had been on the oral medication first to either stay on the oral formulation or continue on the LAI version. Not employing the usual sequence of treatment initiation for LAIs biased the results toward all-cause treatment failure, the primary outcome of the study.120 Considering the real-world adherence advantage of LAIs over oral antipsychotics, the panel recommended early use of LAIs for schizophrenia.

Panel Consensus Statement #2

Importance of Early LAI Intervention: “The panel recommends that initiating LAI treatment early, especially directly after the first episode of schizophrenia, if possible, but at least in the first few years of the illness, can prevent relapses, enhance adherence, and improve symptomatic as well as functional outcomes. Functional recovery, by early use of LAIs, is an important treatment goal in patients with first-episode and early phase schizophrenia.97 Early LAI use is recommended before considering clozapine, in part to assure the absence of pseudo–treatment resistance in the setting of poor adherence to oral medications,121 which should be reserved for patients with true treatment resistance.61,122,123”

Candidates for Treatment with Aripiprazole Monohydrate LAIs

It is important to consider all patient characteristics when evaluating if AOM 400 or Ari 2MRTU 960 is an appropriate treatment option for an individual diagnosed with schizophrenia. In many practices, LAI prescriptions are utilized for patients who are identified as nonadherent to medications. However, studies have shown that physicians often overestimate their patients’ medication adherence rates.124,125 The ideal patient profile for LAI therapy is someone with recent-onset schizophrenia and risk factors for nonadherence, including history of nonadherence to other medications, more severe psychotic symptoms, comorbid substance use, cognitive impairment, poor disease insight, and ambivalence or a negative attitude to diagnosis and medications. Patients on multiple medications are also an ideal target population, as LAI antipsychotic treatment has been shown to reduce overall chlorpromazine equivalent dose, which is a standardized method for comparing antipsychotics. LAI use has also been shown to reduce the overall number of mental health–related medications patients are prescribed.126–129 Other specific patient populations who may benefit from an LAI include patients with a history of multiple hospitalizations or relapses, violent behavior, suicide attempts, or substance abuse; patients with cognitive impairment; or younger patients between the ages of 18 and 35.20,130

Aripiprazole monohydrate LAIs can be an optimal treatment for many patients diagnosed with schizophrenia due to aripiprazole’s mechanism of action, efficacy, and tolerable adverse effect profile. As a dopamine partial agonist, aripiprazole monohydrate is the only LAI option for patients that does not come with a high risk of EPS, hyperprolactinemia, or cardiometabolic adverse effects.78 It has evidence of improved efficacy compared to other LAI medications such as PP1M.80 Additionally, Ari 2MRTU 960 may be administered using a 2-month dosing interval, allowing patients to go to a clinic for injections less frequently, only 6 times a year compared with 12 injections if prescribed for monthly administration. This addresses two common patient concerns and barriers to LAI use: stigma and frequent visits to a healthcare facility for LAI administration.56

Shared decision-making should be utilized for patients who are clinically stable on oral antipsychotics but wish to switch to an LAI formulation. Clinicians and patients should discuss disease stability versus functional recovery and the potential risks and benefits of transitioning to an LAI. Some patients may be clinically stable but have tolerability issues or have residual problematic symptoms that can be expected to improve. These residual issues may prevent achieving components of functional recovery that facilitate autonomy, such as engaging in social relationships or independently completing activities of daily living. Moreover, nonadherence is likely to increase over time within even stable patients, and a meta-analysis found that while stopping antipsychotics posed the highest risk for relapse, followed by lowering the previously effective antipsychotic dose, switching and continuing antipsychotics had similarly protective value in the maintenance treatment of schizophrenia.131 The expert panel recommended that LAIs may be considered as part of a shared-decision making process for patients who are clinically stable on oral antipsychotics, if potential benefits outweigh potential risks. The panel advised that if changes are made, they should be made slowly and carefully to ensure clinical stability is not interrupted.132–134

Starting Aripiprazole Monohydrate LAIs

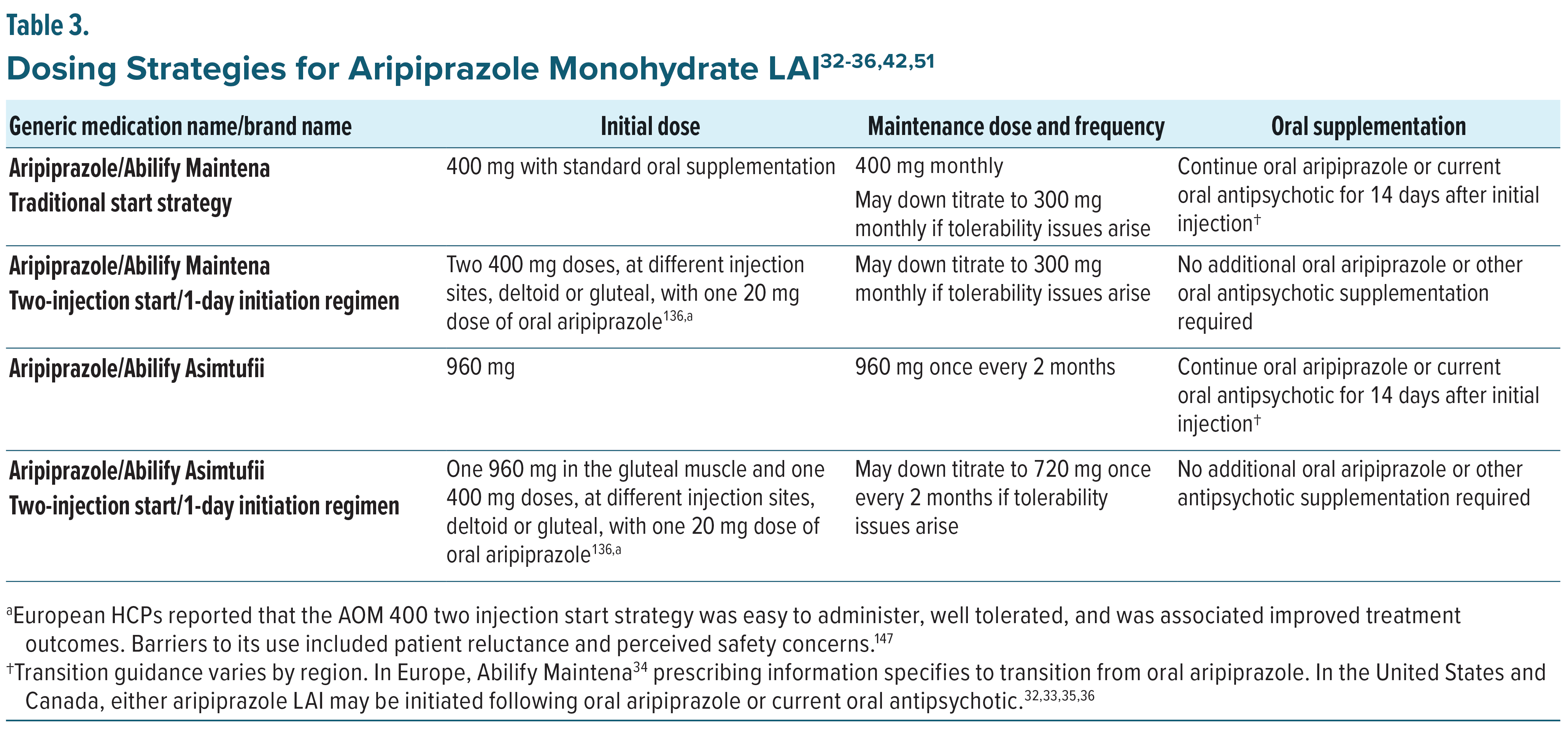

There are multiple strategies for initiating or switching to either of the aripiprazole monohydrate LAI formulations, which have been well characterized in the literature.51,135 The choice of initiation strategy depends on the clinical context and the needs of both the patient and the prescribing clinician. According to the prescribing information in the United States,32,33 Europe,34 and Canada,35,36 in patients naïve to aripiprazole, tolerability should be first established with oral aripiprazole and may take up to 14 days to fully assess prior to initiating either LAI formulation. Once tolerability has been assessed, two recommended start strategies are available, as summarized in Table 3. For AOM 400, the standard initiation approach includes a 14-day oral overlap to maintain therapeutic plasma concentrations while the LAI reaches steady state. In comparison, Ari 2MRTU 960 allows for transition from AOM 400 or from oral aripiprazole after establishing tolerability through various oral dosing regimens.

An alternative to the oral overlap is the two-injection start strategy, which is available for either aripiprazole monohydrate LAI formulation(s). For AOM 400, two injections of AOM 400 mg are administered at separate anatomical sites, deltoid or gluteal, along with a single 20 mg dose of oral aripiprazole.136 For Ari 2MRTU 960, one injection of Ari 2MRTU 960 in the gluteal muscle and one injection of AOM 400 are administered at separate anatomical sites, deltoid or gluteal, along with a single oral dose of aripiprazole 20 mg. Each of these approaches achieves therapeutic plasma concentrations more rapidly and may be particularly useful in settings where immediate and sustained drug exposure is desired, such as acute care or when adherence to oral supplementation is uncertain. Regardless of the approach, both formulations aim to maintain sustained therapeutic drug levels while offering flexibility in treatment planning and the potential to improve adherence through less frequent dosing.136–138

Multidisciplinary and Multimodal Approach to Care

Utilizing aripiprazole monohydrate LAIs as a treatment for schizophrenia symptoms and an aid for functional recovery requires team-based care and appropriate education to support the patient in managing injection administration, missed doses, and potential adverse events.139 The 2020 APA guidelines indicate that psychosocial interventions, such as psychoeducation, cognitive behavioral therapy, social skills training, and lifestyle interventions, are an integral part of clinical care for patients with schizophrenia.108 Utilizing LAIs to minimize symptoms and facilitate medication adherence, in combination with psychosocial interventions to provide the necessary skills for social integration and autonomous daily living, allows patients to manage their condition more fully.140–142 One survey found that patients taking LAIs were able to use psychosocial interventions to work toward functional goals, such as improving relationships, their ability to work, and socialization skills.143 This effect may be due to increased disease insight as a result of assured adherence in patients taking LAIs or reduced medication administration burden. These findings highlight the utility of LAIs as part of a multidisciplinary care plan emphasizing functional recovery.143

Utilizing the care team to its fullest capabilities also improves the clinician-patient relationship and optimizes time spent with the patient to work on additional tools of functional recovery. As time constraints in patient visits and perceived workload increases may prevent prescribers from discussing LAIs as a potential treatment option, empowering non-prescriber care team members to aid in these conversations can be crucial.42,56 Non-prescribers, such as social workers, therapists, nurses, and pharmacists, can play a crucial role in supporting patients treated with LAIs by providing medication education, communicating with patients and prescribers, helping coordinate the treatment plan, and administering LAI doses. Patients often have deep trust in their therapists, which makes them well-suited to discuss treatment satisfaction, review potential medication changes, and advocate for LAIs as a method of self-care. Using a multidisciplinary care approach that integrates LAI antipsychotics allows prescribers to focus on optimizing the patient’s overall medication regimen and the patient’s treatment plan during their visits.144

Panel Consensus Statement #3

Holistic Recovery Approach: “LAIs are seen as enablers of broader recovery goals beyond symptom control. Combining LAI treatment with psychosocial interventions fosters functional recovery,100 allowing patients to achieve better quality of life through improved relationships, employment, and social integration.”

Conclusion

The expert panel concluded that aripiprazole monohydrate LAIs offer a well-established efficacy and tolerability profile for patients with schizophrenia and that aripiprazole is distinguished as the only LAI formulation with a partial dopamine agonist mechanism of action. Its special mechanism of action supports its utility as a frontline option rather than a treatment of last resort. Early introduction of LAIs, paired with clinician and patient education, can shift longstanding misconceptions and reduce stigma surrounding LAI use. A pragmatic approach to treatment suggests the need for ongoing, collaborative efforts with non-physician healthcare providers to introduce aripiprazole monohydrate LAIs as a viable treatment option and provide comprehensive care focused on functional recovery. Integrating aripiprazole monohydrate LAIs earlier in the treatment continuum, through shared decision-making, may facilitate broader adoption and promote sustained symptom control, improved adherence, and functional recovery.

Financial Disclosures

All authors received an honorarium for attendance of the meeting.

Dr Goldberg has received consulting fees from Alvogen Pharmaceuticals and Genomind; has received honoraria for speaking/teaching from Abbvie, Alkermes, Axsome, Bristol-Myers Squibb, and Intracellular Therapies; has received advisory board fees from Luye Pharmaceuticals, Merck, Neurelis, Neuroma, Otsuka, Sunovion, and Supernus; and has received royalties from American Psychiatric Publishing, and Cambridge University Press. Dr Achtyes has received consulting fees from Clinical Care Options, Boehringer-Ingelheim, VML Health, CMEology, CME Outfitters, Otsuka/Lundbeck, and TotalCME; has received grant/research support from Teva, InnateVR, Boehringer-Ingelheim, Neurocrine Biosciences, Karuna/Bristol Myers Squibb, Janssen, Alkermes, Takeda; and has received advisory board fees from Indivior and Alkermes. Dr Correll has stock options in Cardio Diagnostics, Kuleon Biosciences, LB Pharma, Medlink, Mindpax, Quantic, and Terran; has received consulting fees from AbbVie, Acadia, Adock Ingram, Alkermes, Allergan, Angelini, Aristo, Biogen, Boehringer-Ingelheim, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Cardio Diagnostics, Cerevel, CNX Therapeutics, Compass Pathways, Darnitsa, Delpor, Denovo, Eli Lilly, Gedeon Richter, Hikma, Holmusk, IntraCellular Therapies, Jamjoom Pharma, Janssen/J&J, Karuna, LB Pharma, Lundbeck, MedInCell, MedLink, Merck, Mindpax, Mitsubishi Tanabe Pharma, Maplight, Mylan, Neumora Therapeutics, Neurocrine, Neurelis, Newron, Noven, Novo Nordisk, Otsuka, PPD Biotech, Recordati, Relmada, Reviva, Rovi, Sage, Saladax, Sanofi, Seqirus, SK Life Science, Sumitomo Pharma America, Sunovion, Sun Pharma, Supernus, Tabuk, Takeda, Teva, Terran, Tolmar, Vertex, Viatris and Xenon; has received grant/research support from Boehringer-Ingelheim, Janssen, and Takeda; has received honoraria for speaking/teaching from AbbVie, Angelini, Aristo, Boehriger-Ingelheim, Cerevel, Damitsa, Gedeon Richter, Hikma, IntraCellular Therapies, Janssen/J&J, Karuna, Lundbeck, Mitsubishi Tanabe Pharma, Mylan, Otsuka, Recordati, Seqirus, Sunovion, Tabuk, Takeda, and Viatris; has received advisory board fees from AbbVie, Allergan, Angelini, Boehringer Ingelheim, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Cerevel, Compass, Gedeon Richter, Janssen/J&J, Karuna, LB Pharma, Lundbeck, MedInCell, Merck, Neurelis, Neurocrine, Newron, Novo Nordisk, Otsuka, Recordati, Rovi, Sage, Seqirus, Life Science, Sunovion, Supernus, Teva, Vertex, and Viatris; and has received royalties from UpToDate. Dr Sajatovic has received consulting fees from Alkermes, Otsuka, Lundbeck, Janssen, and Teva; has received grant/research support from Neurelis, Intra-Cellular, Merck, Otsuka, Alkermes, International Society for Bipolar Disorders (ISBD), National Institutes of Health (NIH), Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), and Patient-Centered Outcomes Research Institute (PCORI); has received honoraria for speaking/teaching from American Physician’s Institute (CMEtoGo), Psychopharmacology Institute, American Epilepsy Society, and Clinical Care Options; and has received royalties from Springer Press, Johns Hopkins University Press, Oxford Press, and UpToDate. Dr Saklad has received consulting fees from Alkermes, Genomind, Janssen, Karuna, Lundbeck, and Otsuka and has received honoraria for speaking/teaching from Otsuka PsychU, Neurocrine, Teva, and Texas Society of Health System Pharmacists.

References (147)

- GBD 2021 Diseases and Injuries Collaborators. Global incidence, prevalence, years lived with disability (YLDs), disability-adjusted life-years (DALYs), and healthy life expectancy (HALE) for 371 diseases and injuries in 204 countries and territories and 811 subnational locations, 1990–2021: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2021. Lancet. May 18 2024;403(10440):2133–2161. doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(24)00757-8

- American Psychiatric Association. Schizophrenia spectrum and other psychotic disorders.Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders. 2022.

- Kane JM. Treatment strategies to prevent relapse and encourage remission.J Clin Psychiatry. 2007;68 Suppl 14:27–30.

- Novick D, Montgomery W, Treuer T, et al. Relationship of insight with medication adherence and the impact on outcomes in patients with schizophrenia and bipolar disorder: results from a 1-year European outpatient observational study.BMC Psychiatry. Aug 5 2015;15:189. doi.org/10.1186/s12888-015-0560-4

- Emsley R, Chiliza B, Asmal L, et al. The nature of relapse in schizophrenia.BMC Psychiatry. Feb 8 2013;13:50. doi.org/10.1186/1471-244X-13-50

- Kane JM, Kishimoto T, Correll CU. Non-adherence to medication in patients with psychotic disorders: epidemiology, contributing factors and management strategies. World Psychiatry. Oct 2013;12(3):216–26. doi.org/10.1002/wps.20060

- Carbon M, Correll CU. Clinical predictors of therapeutic response to antipsychotics in schizophrenia.Dialogues Clin Neurosci. Dec 2014;16(4):505–24. doi.org/10.31887/DCNS.2014.16.4/mcarbon

- Robinson D, Woerner MG, Alvir JM, et al. Predictors of relapse following response from a first episode of schizophrenia or schizoaffective disorder.Arch Gen Psychiatry. Mar 1999;56(3):241–7. doi.org/10.1001/archpsyc.56.3.241

- Barlati S, Nibbio G, Vita A. Evidence-based psychosocial interventions in schizophrenia: a critical review. Curr Opin Psychiatry. May 1 2024;37(3):131–139. doi.org/10.1097/YCO.0000000000000925

- Correll CU. Using patient-centered assessment in schizophrenia care: defining recovery and discussing concerns and preferences.J Clin Psychiatry. Apr 14 2020;81(3)doi:10.4088/JCP.MS19053BR2C

- Correll CU, Citrome L, Haddad PM, et al. The use of long-acting injectable antipsychotics in schizophrenia: evaluating the evidence.J Clin Psychiatry. 2016;77(suppl 3):1–24. doi.org/10.4088/JCP.15032su1

- Haddad PM, Correll CU. Long-acting antipsychotics in the treatment of schizophrenia: opportunities and challenges. Expert Opin Pharmacother. Mar 2023;24(4):473–493. doi.org/10.1080/14656566.2023.2181073

- Kishimoto T, Hagi K, Kurokawa S, et al. Long-acting injectable versus oral antipsychotics for the maintenance treatment of schizophrenia: a systematic review and comparative meta-analysis of randomised, cohort, and pre-post studies.Lancet Psychiatry. May 2021;8(5):387–404. doi.org/10.1016/s2215-0366(21)00039-0

- Vita G, Pollini D, Canozzi A, et al. Efficacy and acceptability of long-acting antipsychotics in acutely ill individuals with schizophrenia-spectrum disorders: A systematic review and network meta-analysis.Psychiatry Research. 2024/10/01/ 2024;340:116124. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psychres.2024.116124

- Rubio JM, Taipale H, Tanskanen A, Correll CU, Kane JM, Tiihonen J. Long-term continuity of antipsychotic treatment for schizophrenia: a nationwide study. Schizophr Bull. Oct 21 2021;47(6):1611–1620. doi.org/10.1093/schbul/sbab063

- Gharabawi GM, Lasser RA, Bossie CA, et al. Insight and its relationship to clinical outcomes in patients with schizophrenia or schizoaffective disorder receiving long-acting risperidone.International Clinical Psychopharmacology. 2006;21(4):233–240.

- Yen CF, Chen CS, Ko CH, et al. Relationships between insight and medication adherence in outpatients with schizophrenia and bipolar disorder: prospective study.Psychiatry Clin Neurosci. Aug 2005;59(4):403–9. doi.org/10.1111/j.1440-1819.2005.01392.x

- Cipolla S, Catapano P, D’Amico D, et al. Combination of two long-acting antipsychotics in schizophrenia spectrum disorders: a systematic review.Brain Sci. Apr 26 2024;14(5)doi:10.3390/brainsci14050433

- Heres S, Hamann J, Kissling W, Leucht S. Attitudes of psychiatrists toward antipsychotic depot medication. J Clin Psychiatry. Dec 2006;67(12):1948–53. doi.org/10.4088/jcp.v67n1216

- Kane JM, Rubio JM. The place of long-acting injectable antipsychotics in the treatment of schizophrenia. Ther Adv Psychopharmacol. 2023;13:20451253231157219. doi.org/10.1177/20451253231157219

- Kane JM, Schooler NR, Marcy P, et al. Effect of long-acting injectable antipsychotics vs usual care on time to first hospitalization in early-phase schizophrenia: a randomized clinical trial.JAMA Psychiatry. Dec 1 2020;77(12):1217–1224. doi.org/10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2020.2076

- Correll CU, Solmi M, Croatto G, et al. Mortality in people with schizophrenia: a systematic review and meta-analysis of relative risk and aggravating or attenuating factors.World Psychiatry. Jun 2022;21(2):248–271. doi.org/10.1002/wps.20994

- Alphs L, Brown B, Turkoz I, et al. The Disease Recovery Evaluation and Modification (DREaM) study: Effectiveness of paliperidone palmitate versus oral antipsychotics in patients with recent-onset schizophrenia or schizophreniform disorder.Schizophr Res. May 2022;243:86–97. doi.org/10.1016/j.schres.2022.02.019

- Aymerich C, Salazar de Pablo G, Pacho M, et al. All-cause mortality risk in long-acting injectable versus oral antipsychotics in schizophrenia: a systematic review and meta-analysis.Mol Psychiatry. Jan 2025;30(1):263–271. doi.org/10.1038/s41380-024-02694-3

- Alphs L, Baker P, Brown B, Fu DJ, et al. Evaluation of major treatment failure in patients with recent-onset schizophrenia or schizophreniform disorder: A post hoc analysis from the Disease Recovery Evaluation and Modification (DREaM) study.Schizophr Res. Oct 2022;248:58–63. doi.org/10.1016/j.schres.2022.07.015

- Vita G, Tavella A, Ostuzzi G, et al. Efficacy and safety of long-acting injectable versus oral antipsychotics in the treatment of patients with early-phase schizophrenia-spectrum disorders: a systematic review and meta-analysis.Ther Adv Psychopharmacol. 2024;14:20451253241257062. doi.org/10.1177/20451253241257062

- Wei Y, Yan VKC, Kang W, et al. Association of long-acting injectable antipsychotics and oral antipsychotics with disease relapse, health care use, and adverse events among people with schizophrenia.JAMA Netw Open. Jul 1 2022;5(7):e2224163. doi.org/10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2022.24163

- Arango C, Fagiolini A, Gorwood P, et al. Delphi panel to obtain clinical consensus about using long-acting injectable antipsychotics to treat first-episode and early-phase schizophrenia: treatment goals and approaches to functional recovery.BMC Psychiatry. Jun 21 2023;23(1):453. doi.org/10.1186/s12888-023-04928-0

- Velligan DI, Sajatovic M, Hatch A, et al. Why do psychiatric patients stop antipsychotic medication? A systematic review of reasons for nonadherence to medication in patients with serious mental illness.Patient Prefer Adherence. 2017;11:449–468. doi.org/10.2147/ppa.S124658

- Guo J, Lv X, Liu Y, Kong L, et al. Influencing factors of medication adherence in schizophrenic patients: a meta-analysis.Schizophrenia (Heidelb). May 15 2023;9(1):31. doi.org/10.1038/s41537-023-00356-x

- Citrome L, Correll CU, Cutler AJ, et al. Aripiprazole lauroxil: development and evidence-based review of a long-acting injectable atypical antipsychotic for the treatment of schizophrenia.Neuropsychiatr Dis Treat. 2025;21:575–596. doi.org/10.2147/NDT.S499367

- ABILIFY MAINTENA (aripiprazole) for extended-release injectable suspension, for intramuscular use [package insert]. Otsuka America Pharmaceutical, Inc.2025.

- ABILIFY ASIMTUFII (aripiprazole) extended-release injectable suspension, for intramuscular use [package insert]. Otsuka America Pharmaceutical, Inc.2025.

- European Medicines Agency. Abilify Maintena. European Medicines Agency. Updated April 7, 2024. Accessed March 28, 2025. https://www.ema.europa.eu/en/medicines/human/EPAR/abilify-maintena

- ABILIFY MAINTENA (aripiprazole) for extended-release injectable suspension 300 and 400 mg per vial, intramuscular use [product monograph]. Otsuka Canada Pharmaceutical, Inc; 2025.

- ABILIFY ASIMTUFII (aripiprazole) prolonged release injectable suspension 720 mg/2.4 mL and 960 mg/3.2 mL, intramuscular injection [product monograph]. Otsuka Canada Pharmaceutical, Inc; 2025.

- Mailman RB, Murthy V. Third generation antipsychotic drugs: partial agonism or receptor functional selectivity? Curr Pharm Des. 2010;16(5):488–501. doi.org/10.2174/138161210790361461

- de Bartolomeis A, Tomasetti C, Iasevoli F. Update on the mechanism of action of aripiprazole: translational insights into antipsychotic strategies beyond dopamine receptor antagonism.CNS Drugs. Sep 2015;29(9):773–99. doi.org/10.1007/s40263-015-0278-3

- Kane JM, Correll CU. Past and present progress in the pharmacologic treatment of schizophrenia. J Clin Psychiatry. Sep 2010;71(9):1115–24. doi.org/10.4088/JCP.10r06264yel

- Solmi M, Seitidis G, Mavridis D, et al. Incidence, prevalence, and global burden of schizophrenia - data, with critical appraisal, from the Global Burden of Disease (GBD) 2019.Mol Psychiatry. Dec 2023;28(12):5319–5327. doi.org/10.1038/s41380-023-02138-4

- Solmi M, Murru A, Pacchiarotti I, et al. Safety, tolerability, and risks associated with first- and second-generation antipsychotics: a state-of-the-art clinical review.Ther Clin Risk Manag. 2017;13:757–777. doi.org/10.2147/TCRM.S117321

- Kane JM, McEvoy JP, Correll CU, et al. Controversies surrounding the use of long-acting injectable antipsychotic medications for the treatment of patients with schizophrenia.CNS Drugs. 2021;35(11):1189–1205. doi.org/10.1007/s40263-021-00861-6

- Burschinski A, Schneider-Thoma J, Chiocchia V, et al. Metabolic side effects in persons with schizophrenia during mid- to long-term treatment with antipsychotics: a network meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials.World Psychiatry. Feb 2023;22(1):116–128. doi.org/10.1002/wps.21036

- Pillinger T, McCutcheon RA, Vano L, et al. Comparative effects of 18 antipsychotics on metabolic function in patients with schizophrenia, predictors of metabolic dysregulation, and association with psychopathology: a systematic review and network meta-analysis.Lancet Psychiatry. Jan 2020;7(1):64–77. doi.org/10.1016/S2215-0366(19)30416-X

- Yonezawa K, Kanegae S, Ozawa H. Antipsychotics/neuroleptics: pharmacology and biochemistry. 2021:1–10.

- Pillinger T, Howes OD, Correll CU, et al. Antidepressant and antipsychotic side-effects and personalised prescribing: a systematic review and digital tool development.Lancet Psychiatry. Nov 2023;10(11):860–876. doi.org/10.1016/S2215-0366(23)00262-6

- Firth J, Siddiqi N, Koyanagi A, et al. The Lancet Psychiatry Commission: a blueprint for protecting physical health in people with mental illness.Lancet Psychiatry. Aug 2019;6(8):675–712. doi.org/10.1016/S2215-0366(19)30132-4

- Misawa F, Kishimoto T, Hagi K, et al. Safety and tolerability of long-acting injectable versus oral antipsychotics: A meta-analysis of randomized controlled studies comparing the same antipsychotics.Schizophr Res. Oct 2016;176(2–3):220–230. doi.org/10.1016/j.schres.2016.07.018

- Correll CU, Kim E, Sliwa JK, et al. Pharmacokinetic characteristics of long-acting injectable antipsychotics for schizophrenia: an overview.CNS Drugs. 2021;35(1):39–59. doi.org/10.1007/s40263-020-00779-5

- Bloch Y, Mendlovic S, Strupinsky S, et al. Injections of depot antipsychotic medications in patients suffering from schizophrenia: do they hurt? J Clin Psychiatry. Nov 2001;62(11):855–9. doi.org/10.4088/jcp.v62n1104

- Højlund M, Correll CU. Switching to long-acting injectable antipsychotics: pharmacological considerations and practical approaches. Expert Opinion on Pharmacotherapy. 2023;24(13):1463–1489. doi.org/10.1080/14656566.2023.2228686

- Shapiro DA, Renock S, Arrington E, et al. Aripiprazole, a novel atypical antipsychotic drug with a unique and robust pharmacology.Neuropsychopharmacology. Aug 2003;28(8):1400–11. doi.org/10.1038/sj.npp.1300203

- Fleischhacker WW, Sanchez R, Perry PP, et al. Aripiprazole once-monthly for treatment of schizophrenia: double-blind, randomised, non-inferiority study.Br J Psychiatry. Aug 2014;205(2):135–44. doi.org/10.1192/bjp.bp.113.134213

- Nasrallah HA. The case for long-acting antipsychotic agents in the post-CATIE era. Acta Psychiatr Scand. Apr 2007;115(4):260–7. doi.org/10.1111/j.1600-0447.2006.00982.x

- Arango C, Baeza I, Bernardo M, et al. Long-acting injectable antipsychotics for the treatment of schizophrenia in Spain.Rev Psiquiatr Salud Ment (Engl Ed). Apr-Jun 2019;12(2):92–105. Antipsicoticos inyectables de liberacion prolongada para el tratamiento de la esquizofrenia en Espana. doi.org/10.1016/j.rpsm.2018.03.006

- Parellada E, Bioque M. Barriers to the Use of Long-Acting Injectable Antipsychotics in the Management of Schizophrenia.CNS Drugs. Aug 2016;30(8):689–701. doi.org/10.1007/s40263-016-0350-7

- Cahling L, Berntsson A, Bröms G, et al. Perceptions and knowledge of antipsychotics among mental health professionals and patients.BJPsych Bull. Oct 2017;41(5):254–259. doi.org/10.1192/pb.bp.116.055483

- National Alliance of State Pharmacy Associations. Pharmacist Administration of Long-Acting Injectable Antipsychotics. Updated June 3, 2024. Accessed January 14, 2025, https://naspa.us/blog/resource/med-admin-resources/

- Murphy AL, Suh S, Gillis L, et al. Pharmacist administration of long-acting injectable antipsychotics to community-dwelling patients: a scoping review.Pharmacy (Basel). Feb 27 2023;11(2)doi:10.3390/pharmacy11020045

- Jaeger M, Rossler W. Attitudes towards long-acting depot antipsychotics: a survey of patients, relatives and psychiatrists.Psychiatry Res. Jan 30 2010;175(1-2):58–62. doi.org/10.1016/j.psychres.2008.11.003

- McCutcheon RA, Pillinger T, Varvari I, et al. INTEGRATE: international guidelines for the algorithmic treatment of schizophrenia.Lancet Psychiatry. Mar 31 2025;doi:10.1016/S2215-0366(25)00031-8

- Caroli F, Raymondet P, Izard I, et al. Opinions of French patients with schizophrenia regarding injectable medication.Patient Prefer Adherence. Mar 21 2011;5:165–71. doi.org/10.2147/ppa.S15337

- Katz EG, Hauber B, Gopal S, et al. Physician and patient benefit-risk preferences from two randomized long-acting injectable antipsychotic trials.Patient Prefer Adherence. 2016;10:2127–2139. doi.org/10.2147/ppa.S114172

- Kane JM, Schooler NR, Marcy P, et al. Patients with early-phase schizophrenia will accept treatment with sustained-release medication (long-acting injectable antipsychotics): results from the recruitment phase of the PRELAPSE Trial.J Clin Psychiatry. Apr 23 2019;80(3)doi:10.4088/JCP.18m12546

- Correll CU, Rubio JM, Citrome L, et al. Introducing S.C.O.P.E. (Schizophrenia Clinical Outcome Scenarios and Patient-Provider Engagement), an interactive digital platform to educate healthcare professionals on schizophrenia care.Neuropsychiatr Dis Treat. 2024;20:1995–2010. doi.org/10.2147/NDT.S477674

- Strassnig M, Bowie C, Pinkham AE, et al. Which levels of cognitive impairments and negative symptoms are related to functional deficits in schizophrenia? J Psychiatr Res. Sep 2018;104:124–129. doi.org/10.1016/j.jpsychires.2018.06.018

- Correll CU, Schooler NR. Negative symptoms in schizophrenia: a review and clinical guide for recognition, assessment, and treatment. Neuropsychiatr Dis Treat. 2020;16:519–534. doi.org/10.2147/NDT.S225643

- Huhn M, Nikolakopoulou A, Schneider-Thoma J, et al. Comparative efficacy and tolerability of 32 oral antipsychotics for the acute treatment of adults with multi-episode schizophrenia: a systematic review and network meta-analysis.Lancet. Sep 14 2019;394(10202):939–951. doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(19)31135-3

- Ostuzzi G, Bertolini F, Tedeschi F, et al. Oral and long-acting antipsychotics for relapse prevention in schizophrenia-spectrum disorders: a network meta-analysis of 92 randomized trials including 22,645 participants.World Psychiatry. Jun 2022;21(2):295–307. doi.org/10.1002/wps.20972

- Ostuzzi G, Bertolini F, Del Giovane C, et al. Maintenance treatment with long-acting injectable antipsychotics for people with nonaffective psychoses: a network meta-analysis.Am J Psychiatry. May 1 2021;178(5):424–436. doi.org/10.1176/appi.ajp.2020.20071120

- Kantrowitz JT. How do we address treating the negative symptoms of schizophrenia pharmacologically?Expert Opin Pharmacother. Oct 2021;22(14):1811–1813. doi.org/10.1080/14656566.2021.1939677

- Tamminga CA. Partial dopamine agonists in the treatment of psychosis.J Neural Transm (Vienna). Mar 2002;109(3):411–20. doi.org/10.1007/s007020200033

- Correll CU, Abi-Dargham A, Howes O. Emerging treatments in schizophrenia.J Clin Psychiatry. Feb 15 2022;83(1)doi:10.4088/JCP.SU21024IP1

- McCutcheon R, Beck K, Jauhar S, Howes OD. Defining the locus of dopaminergic dysfunction in schizophrenia: a meta-analysis and test of the mesolimbic hypothesis.Schizophr Bull. Oct 17 2018;44(6):1301–1311. doi.org/10.1093/schbul/sbx180

- Stelmach A, Guzek K, Rożnowska A, et al. Antipsychotic drug—aripiprazole against schizophrenia, its therapeutic and metabolic effects associated with gene polymorphisms.Pharmacological Reports. 2023/02/01 2023;75(1):19–31. doi.org/10.1007/s43440-022-00440-6

- Carbon M, Hsieh CH, Kane JM, et al. Tardive dyskinesia prevalence in the period of second-generation antipsychotic use: a meta-analysis.J Clin Psychiatry. Mar 2017;78(3):e264-e278. doi.org/10.4088/JCP.16r10832

- Carbon M, Kane JM, Leucht S, et al. Tardive dyskinesia risk with first- and second-generation antipsychotics in comparative randomized controlled trials: a meta-analysis.World Psychiatry. Oct 2018;17(3):330–340. doi.org/10.1002/wps.20579

- Di Sciascio G, Riva MA. Aripiprazole: from pharmacological profile to clinical use. Neuropsychiatr Dis Treat. 2015;11:2635–47. doi.org/10.2147/ndt.S88117

- Kane JM, Sanchez R, Perry PP, et al. Aripiprazole intramuscular depot as maintenance treatment in patients with schizophrenia: a 52-week, multicenter, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled study.J Clin Psychiatry. May 2012;73(5):617–24. doi.org/10.4088/JCP.11m07530

- Naber D, Hansen K, Forray C, et al. Qualify: a randomized head-to-head study of aripiprazole once-monthly and paliperidone palmitate in the treatment of schizophrenia.Schizophr Res. Oct 2015;168(1–2):498–504. doi.org/10.1016/j.schres.2015.07.007

- Kane JM, Zhao C, Johnson BR, et al. Hospitalization rates in patients switched from oral anti-psychotics to aripiprazole once-monthly: final efficacy analysis.J Med Econ. Feb 2015;18(2):145–54. doi.org/10.3111/13696998.2014.979936

- Harlin M, Yildirim M, Such P, et al. A randomized, open-label, multiple-dose, parallel-arm, pivotal study to evaluate the safety, tolerability, and pharmacokinetics of aripiprazole 2-month long-acting injectable in adults with schizophrenia or bipolar i disorder.CNS Drugs. Apr 2023;37(4):337–350. doi.org/10.1007/s40263-023-00996-8

- Harlin M, Chepke C, Larsen F, et al. Aripiprazole plasma concentrations delivered from two 2-month long-acting injectable formulations: an indirect comparison.Neuropsychiatr Dis Treat. 2023;19:1409–1416. doi.org/10.2147/NDT.S412357

- Citrome L, Such P, Yildirim M, et al. Safety and efficacy of aripiprazole 2-month ready-to-use 960 mg: secondary analysis of outcomes in adult patients with schizophrenia in a randomized, open-label, parallel-arm, pivotal study.J Clin Psychiatry. Sep 4 2023;84(5)doi:10.4088/JCP.23m14873

- Tandon R, Lenderking WR, Weiss C, et al. The impact on functioning of second-generation antipsychotic medication side effects for patients with schizophrenia: a worldwide, cross-sectional, web-based survey.Ann Gen Psychiatry. 2020;19:42. doi.org/10.1186/s12991-020-00292-5

Dibonaventura M, Gabriel S, Dupclay L, et al. A patient perspective of the impact of medication side effects on adherence: results of a cross-sectional nationwide survey of patients with schizophrenia.BMC Psychiatry. Mar 20 2012;12:20. doi.org/10.1186/1471-244x-12-20

Semahegn A, Torpey K, Manu A, et al. Psychotropic medication non-adherence and its associated factors among patients with major psychiatric disorders: a systematic review and meta-analysis.Systematic Reviews. 2020/01/16 2020;9(1):17. doi.org/10.1186/s13643-020-1274-3

- World Health Organization. Adherence to long-term therapies : evidence for action. Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization; 2003.

Weiden PJ, Kozma C, Grogg A, et al. Partial compliance and risk of rehospitalization among California Medicaid patients with schizophrenia.Psychiatr Serv. Aug 2004;55(8):886–91. doi.org/10.1176/appi.ps.55.8.886

Takeuchi H, Siu C, Remington G, et al. Does relapse contribute to treatment resistance? Antipsychotic response in first- vs. second-episode schizophrenia.Neuropsychopharmacology. May 2019;44(6):1036–1042. doi.org/10.1038/s41386-018-0278-3

Andreasen NC, Liu D, Ziebell S, et al. Relapse duration, treatment intensity, and brain tissue loss in schizophrenia: a prospective longitudinal MRI study.American Journal of Psychiatry. 2013;170(6):609–615. doi.org/10.1176/appi.ajp.2013.12050674

Tishler TA, Ellingson BM, Salvadore G, et al. Effect of treatment with paliperidone palmitate versus oral antipsychotics on frontal lobe intracortical myelin volume in participants with recent-onset schizophrenia: Magnetic resonance imaging results from the DREaM study.Schizophr Res. May 2023;255:195–202. doi.org/10.1016/j.schres.2023.03.023

Basu A, Patel C, Fu AZ, et al. Real-world calibration and transportability of the Disease Recovery Evaluation and Modification (DREaM) randomized clinical trial in adult Medicaid beneficiaries with recent-onset schizophrenia.J Manag Care Spec Pharm. Mar 2023;29(3):293–302. doi.org/10.18553/jmcp.2023.22191

- Williamson DJ, Nuechterlein KH, Tishler T, et al. Dispersion of cognitive performance test scores on the MATRICS Consensus Cognitive Battery: A different perspective.Schizophr Res Cogn. Dec 2022;30:100270. doi.org/10.1016/j.scog.2022.100270

- Bartzokis G, Lu PH, Stewart SB, et al. In vivo evidence of differential impact of typical and atypical antipsychotics on intracortical myelin in adults with schizophrenia.Schizophr Res. Sep 2009;113(2-3):322–31. doi.org/10.1016/j.schres.2009.06.014

Correll CU, Benson C, Emond B, et al. Comparison of clinical outcomes in patients with schizophrenia following different long-acting injectable event-driven initiation strategies.Schizophrenia (Heidelb). Feb 11 2023;9(1):9. doi.org/10.1038/s41537-023-00334-3

- Gorwood P, Yildirim M, Madera-McDonough J, et al. Assessment of functional recovery in patients with schizophrenia, with a focus on early-phase disease: results from a Delphi consensus and narrative review.BMC Psychiatry. Apr 17 2025;25(1):398. doi.org/10.1186/s12888-025-06725-3

Olagunju AT, Clark SR, Baune BT. Long-acting atypical antipsychotics in schizophrenia: A systematic review and meta-analyses of effects on functional outcome.Aust N Z J Psychiatry. Jun 2019;53(6):509–527. doi.org/10.1177/0004867419837358

Correll CU, Galling B, Pawar A, et al. Comparison of early intervention services vs treatment as usual for early-phase psychosis: a systematic review, meta-analysis, and meta-regression.JAMA Psychiatry. Jun 1 2018;75(6):555–565. doi.org/10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2018.0623

- Solmi M, Taipale H, Holm M, et al. effectiveness of antipsychotic use for reducing risk of work disability: results from a within-subject analysis of a Swedish national cohort of 21,551 patients with first-episode nonaffective psychosis.Am J Psychiatry. Dec 1 2022;179(12):938–946. doi.org/10.1176/appi.ajp.21121189

- Takács P, Czobor P, Fehér L, et al. Comparative effectiveness of second generation long-acting injectable antipsychotics based on nationwide database research in Hungary.PLoS One. 2019;14(6):e0218071. doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0218071

- Basu A, Benson C, Turkoz I, et al. Health care resource utilization and costs in patients receiving long-acting injectable vs oral antipsychotics: A comparative analysis from the Disease Recovery Evaluation and Modification (DREaM) study.J Manag Care Spec Pharm. Oct 2022;28(10):1086–1095. doi.org/10.18553/jmcp.2022.28.10.1086

- Fusar-Poli P, Salazar de Pablo G, Correll CU, et al. Prevention of psychosis: advances in detection, prognosis, and intervention.JAMA Psychiatry. Jul 1 2020;77(7):755–765. doi.org/10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2019.4779

- Salazar de Pablo G, Besana F, Arienti V, et al. Longitudinal outcome of attenuated positive symptoms, negative symptoms, functioning and remission in people at clinical high risk for psychosis: a meta-analysis.EClinicalMedicine. Jun 2021;36:100909. doi.org/10.1016/j.eclinm.2021.100909

- Kane JM, Robinson DG, Schooler NR, et al. comprehensive versus usual community care for first-episode psychosis: 2-year outcomes from the NIMH RAISE early treatment program.Am J Psychiatry. Apr 1 2016;173(4):362–72. doi.org/10.1176/appi.ajp.2015.15050632

- Lopena OJ, Alphs LD, Sajatovic M, et al. Earlier use of long-acting injectable paliperidone palmitate versus oral antipsychotics in patients with schizophrenia: an integrated patient-level post hoc analysis.J Clin Psychiatry. Sep 25 2023;84(6)doi:10.4088/JCP.23m14788

- Subotnik KL, Casaus LR, Ventura J, et al. Long-acting injectable risperidone for relapse prevention and control of breakthrough symptoms after a recent first episode of schizophrenia: a randomized clinical trial.JAMA Psychiatry. 2015;72(8):822–829. doi.org/10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2015.0270

- Keepers GA, Fochtmann LJ, Anzia JM, et al. The American Psychiatric Association Practice Guideline for the Treatment of Patients With Schizophrenia.Am J Psychiatry. Sep 1 2020;177(9):868–872. doi.org/10.1176/appi.ajp.2020.177901

- Correll CU, Martin A, Patel C, et al. Systematic literature review of schizophrenia clinical practice guidelines on acute and maintenance management with antipsychotics.Schizophrenia (Heidelb). Feb 24 2022;8(1):5. doi.org/10.1038/s41537-021-00192-x