Abstract

Objective: To assess proof-of-concept (PoC) for efficacy, tolerability, and safety of TRPC4/5 inhibitor BI 1358894 vs placebo in patients with major depressive disorder (MDD) with inadequate response to ongoing antidepressants.

Methods: In this phase 2, multicenter, randomized, double-blind, dose-finding trial (December 2020–February 2024), patients with MDD (per DSM-5) and current depressive episode of ≥8 weeks and ≤24 months were randomized (3.5:1:1:1:2:2) to receive placebo or BI 1358894 (5 mg, 25 mg, 75 mg, or 125 mg) or quetiapine 150–300 mg orally, once daily for 6 weeks. Primary end point was change from baseline in Montgomery-Åsberg Depression Rating Scale (MADRS) total score at Week 6. Secondary end points included ≥50% reduction from baseline in MADRS total score at Week 6, change from baseline in State-Trait Anxiety Inventory scores, Clinical Global Impression Severity Scale score, and Symptoms of Major Depressive Disorder Scale total score at Week 6.

Results: Of 940 enrolled patients, 389 were randomized, and 361 (93.0%) completed the trial. No differences were observed between BI 1358894 treatment groups and placebo for primary and secondary end points. Adverse events were slightly more frequent in the BI 1358894-total group (66.7%) vs placebo (53.9%). No worsening of Columbia-Suicide Severity Rating Scale was observed for most patients; serious adverse events of suicidal ideation were reported for 4.7% (placebo), 5.1% (BI 1358894 75 mg group), and 1.4% (quetiapine) of patients.

Conclusion: Although this was a negative trial in MDD with PoC not established, BI 1358894 was well tolerated with no increase in self-harm or suicidality.

Trial Registration: ClinicalTrials.gov identifier: NCT04521478.

J Clin Psychiatry 2025;86(3):25m15868

Author affiliations are listed at the end of this article.

Major depressive disorder (MDD) is a prevalent condition that is challenging to treat despite the availability of a wide variety of antidepressant treatments.1 Approximately 30% of patients with MDD do not reach remission even after 4 medication steps and continue to experience residual symptoms and poor quality of life.2,3 Additionally, patients with MDD exhibit a higher mortality rate relative to the general population,4–6 with an 8.62 times greater likelihood of dying by suicide.7

Most clinical guidelines recommend selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs), serotonin norepinephrine reuptake inhibitors (SNRIs), or bupropion (norepinephrine-dopamine reuptake inhibitor) as the first-line pharmacologic treatment for MDD.8–11 When monotherapy with first-line treatments is ineffective, common management strategies involve switching to a different antidepressant within the same or different class, combining antidepressants, or using adjuncts such as lithium or atypical antipsychotics in addition to first-line treatments.10,12,13 The commonly prescribed adjuncts are associated with an increased side-effect burden, which can restrict their applicability.10,14 Given the limitations of existing treatments and the high disease burden of MDD, there is a pressing need for new and effective treatments.

A potential pathophysiological mechanism underlying MDD involves an imbalance in the corticolimbic circuitry.15,16 Transient receptor potential canonical ion channels 4 and 5 (TRPC4/5) are involved in the regulation of neuronal excitability and are primarily expressed in brain areas associated with emotion and mood, including the corticolimbic system including the amygdala.17,18 BI 1358894 is a TRPC4/5 inhibitor in development for symptomatic treatment of MDD, which is theorized to address symptoms of depression through attenuation of amygdala hyperreactivity.19 As such, BI 1358894 may represent a potential new alternative to existing adjunctive treatments for MDD. In phase 1 trials of healthy volunteers, BI 1358894 reduced psychological and physiological responses to cholecystokinin-tetrapeptide (CCK-4) induced panic symptoms20 and was found to be well tolerated with a favorable pharmacokinetic profile.21,22 The present trial was conducted to provide proof-of-concept (PoC) for TRPC4/5 ion channel inhibition and dose-ranging data for BI 1358894 vs placebo in patients with MDD with inadequate response to ongoing antidepressants, in order to support dose selection for pivotal studies. Additionally, the safety and tolerability of BI 1358894 was assessed.

METHODS

Trial Design, Randomization, and Blinding

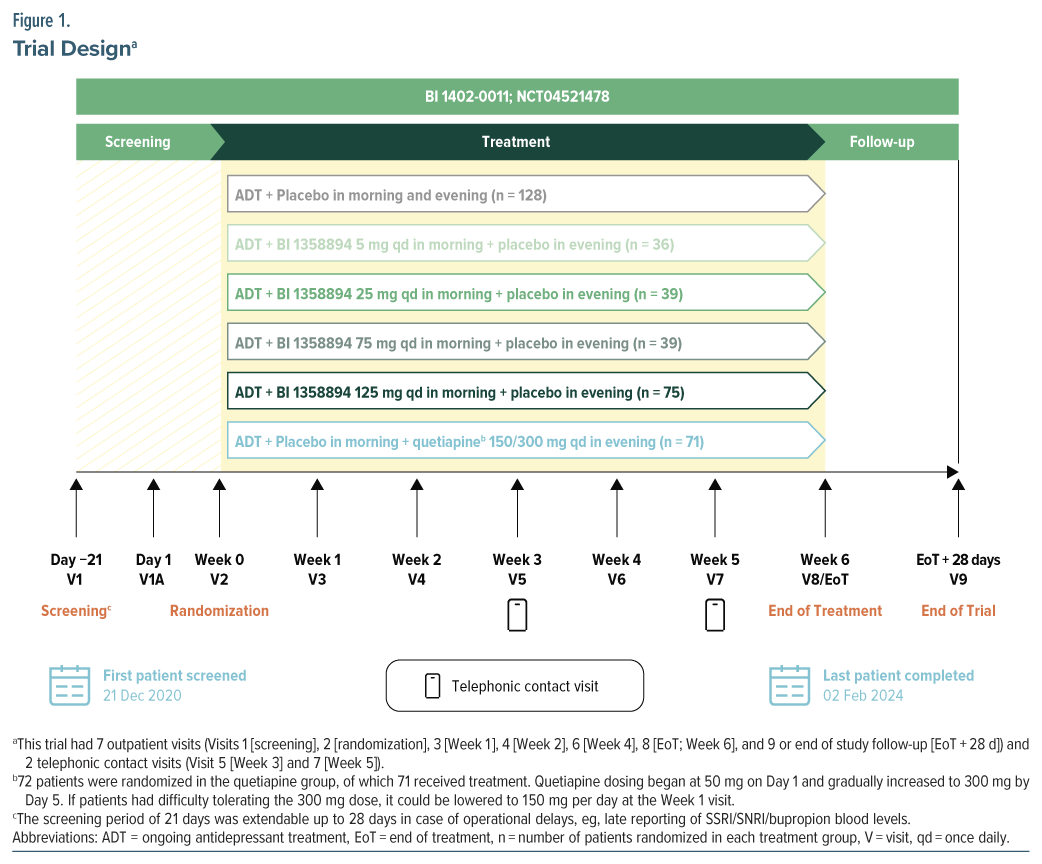

This was a phase 2, multicenter, randomized, double-blind, double-dummy, placebo-controlled, parallel group trial (ClinicalTrials.gov identifier: NCT04521478), with an additional quetiapine group, in patients with MDD with inadequate response to ongoing antidepressants (Figure 1). This trial was conducted in 120 sites in 14 countries between December 21, 2020, and February 2, 2024 (Supplementary Figure 1). Eligible patients with documented ongoing antidepressants (SSRI/SNRI/bupropion) were randomized to receive placebo or BI 1358894 (5 mg, 25 mg, 75 mg, or 125 mg) or quetiapine extended release 150–300 mg orally, once daily in a 3.5:1:1:1:2:2 ratio for 6 weeks. Randomization codes were computer-generated by a specialized randomization group within the sponsor company. Based on these codes, the allocation of patients to treatment was performed using an interactive response technology run by an external vendor. Access to the randomization code was controlled and documented. The clinical trial team remained blinded to the randomized treatment assignments until the final database lock, with one prespecified exception. To facilitate the exclusion of pharmacokinetic (PK) samples from placebo participants in the analyses, randomization codes were provided to the bioanalytics team prior to the last participant completing the trial. However, these randomization codes and the PK results remained undisclosed until the trial was officially unblinded.

Randomization into each treatment group was stratified by baseline severity of MDD (baseline Montgomery-Åsberg Depression Rating Scale [MADRS] score ≤19 vs >19). Randomization occurred up to 3 weeks after screening, and fluctuations in depressive symptoms could be expected; therefore, no MADRS cutoff was imposed at the randomization visit to avoid potential inflation of baseline severity.

Medication kits corresponding to assigned medication numbers were given to patients. Using this procedure, patients and trial staff were blinded to treatment group assignments. BI 1358894 tablets or matching placebos were administered orally every morning. The selection of BI 1358894 doses (5 mg, 25 mg, 75 mg, and 125 mg) was guided by preclinical findings and PK data from prior phase 1 studies.21,23 The half maximal effective concentration (EC50) from preclinical studies was used to select the target total plasma concentration in humans. Considering the limitations and uncertainties associated with preclinical animal tests in predicting antidepressive efficacy in humans, an adequate multiple above and below this target dose was explored in this clinical dose range finding study, leading to the dose range of 5 mg to 125 mg.

Quetiapine is a commonly recommended adjunctive agent in patients with inadequate response to antidepressant monotherapy.10,13 Therefore, a quetiapine treatment group was included in this trial for reference. Quetiapine or matching placebo was administered orally every evening. Adherence was measured using the traditional tablet-counting method, plus by video-monitoring using a smartphone application.

Using a multiple comparison procedure with modeling (MCPMod) approach, a total sample size of approximately 431 patients was needed to determine PoC with 81% average power across models, with 1-sided 10% α level, assuming a 30% dropout rate and 281 evaluable patients across the placebo and BI 1358894 treatment groups.

The trial was conducted in accordance with the principles of the Declaration of Helsinki, the International Council for Harmonisation of Good Clinical Practice guidelines, applicable regulatory requirements, and Boehringer Ingelheim standard operating procedures. The clinical trial protocol and informed consent form were approved by the Independent Ethics Committees and/or Institutional Review Boards of the participating centers.

Participants

The trial included patients aged 18–65 years, with an established diagnosis of MDD (per Structured Clinical Interview for Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fifth Edition) at screening who provided informed consent. In order to exclude chronic forms of depression and ensure a more homogeneous MDD sample, patients were required to be experiencing a current depressive episode of ≥8 weeks and ≤24 months. Eligibility criteria also included a MADRS total score ≥24 (confirmed by a trained site-based rater and computer-administered patient-reported MADRS) and a score ≥3 on the Reported Sadness Item, along with documented ongoing antidepressant monotherapy (protocol specified SSRI or SNRI, or bupropion) of ≥4 weeks at the screening visit as confirmed by detectable drug levels in urine or blood samples. Patients were excluded at screening if they had ever met diagnostic criteria for a psychotic disorder, had a diagnosis of any other psychiatric disorder as the primary focus of treatment within 6 months prior to screening, had a history of major neurological illness, or had a diagnosis of any personality disorder that could impact trial participation, or a substance abuse disorder, within 3 months prior to screening. Patients with suicidal behavior 12 months prior to screening or a Columbia-Suicide Severity Rating Scale (C-SSRS) score of 4 or 5 in the 3 months prior to screening or at screening or baseline visit were also excluded. Patients could have no more than two unsuccessful monotherapy treatments with an approved antidepressant (SSRI/SNRI/bupropion) at adequate dose and duration for the current ongoing major depressive episode. The full eligibility criteria and the protocol amendments for the inclusion criteria are presented in the Supplementary Materials.

End Points and Assessments

Primary end point. The primary end point was change from baseline in MADRS total score at Week 6. The MADRS includes 10 items that measure core symptoms of depression. Each item is scored from 0 (indicating no abnormality) to 6 (indicating severe symptoms), with total scores spanning from 0 (no symptoms) to 60 (high severity).24 Subgroup analyses of the primary end point were conducted for baseline disease severity, demographics (sex, age group, concomitant psychotherapy use, type of background medication, race [White/non-White, Asian/non-Asian], and region), and overall medication adherence.

Secondary end points. Secondary end points were treatment response (defined as ≥50% reduction from baseline in MADRS total score) at Week 6, change from baseline in the State-Trait Anxiety Inventory (STAI) State and Trait version total scores,25 Clinical Global Impression Severity Scale (CGI-S) score,26 and Symptoms of Major Depressive Disorder Scale (SMDDS)27 total score at Week 6.

Exploratory end points. The key exploratory end points included BI 1358894 plasma concentration, relative percent change from baseline in total MADRS score over time, remission defined as MADRS score ≤10 at Week 6, and change from baseline in STAI, CGI-S, and SMDDS scores over time. Other exploratory end points are summarized in the Supplementary Materials.

Safety and Tolerability

The percentages of patients with adverse events (AEs), serious AEs (SAEs), AEs of special interest (AESI) were recorded. The prespecified AESI was hepatic injury, which included an elevation of aminotransferase [aspartate transaminase {AST} and/ or alanine transaminase {ALT}] ≥3-fold upper limit of normal [ULN] combined with total bilirubin elevation ≥2-fold ULN measured in the same blood sample, or aminotransferase [ALT and/or AST] elevations ≥10- fold ULN), and extrapyramidal AEs were recorded. Suicidal risk was assessed by the C-SSRS. Any clinically significant abnormalities in physical examination, vital signs, 12-lead electrocardiogram (ECG), and laboratory tests were also reported.

Statistical Analysis

Primary analysis of the primary end point used a hypothetical estimand, which focused on the treatment effect assuming that the trial medication was taken as directed and excluding intercurrent events, including all data collected while on treatment from the first dose of trial medication to the last dose plus 7 days. Any data collected after a patient discontinued treatment, regardless of the reason, were not included in the primary analysis. MCPMod was used to evaluate several possible dose-response models to identify the best-fitting model based on BI 1358894 and placebo treatment groups (refer to the Supplementary Materials for details). If at least one dose-response model showed statistical significance, demonstrating a nonflat dose-response curve for change from baseline in MADRS total score at Week 6, indicating a benefit of at least one BI 1358894 dose over placebo, this would establish PoC.

As a basis for the MCPMod analysis and to assess quantitative treatment benefit, a mixed model for repeated measure (MMRM) analysis was used to generate covariate adjusted estimates of mean change from baseline to Week 6 in MADRS total score and associated covariance matrices. The MMRM included discrete fixed effects for baseline MADRS severity level, treatment at each visit, concomitant psychotherapy use, and the continuous effects of baseline. No formal hypothesis tests were performed to compare BI 1358894 and quetiapine or to compare quetiapine and placebo as the trial was not statistically powered for such comparisons. However, an exploratory post hoc MMRM analysis was conducted for the primary end point to assess potential trends in quetiapine treatment effects compared to placebo and all doses of BI 1358894. Descriptive summaries of quetiapine and placebo responses were used to assess the impact of placebo response.

For the secondary end point of treatment response (≥50% reduction in MADRS total score from baseline), the proportion of participants achieving response for each analysis visit up to Week 6 was summarized as the frequency and percentage of participants in each treatment arm. MADRS response up to Week 6 was analyzed using a logistic regression model, including fixed categorical effects of treatment and baseline MDD severity. For the other secondary end points, a similar MMRM approach was used to obtain the adjusted change from baseline at Week 6 for each of the BI treatment groups vs placebo. All end points were summarized descriptively.

Efficacy was assessed for the full analysis set; ie, all randomized patients who received ≥1 dose of trial medication during the trial had a baseline and ≥1 evaluable postbaseline measurement for the primary end point. Safety analyses were conducted on the treated set (TS), ie, all randomized patients who received ≥1 dose of the trial medication. BI 1358894 plasma concentration was assessed for all patients in the TS who had ≥1 evaluable PK plasma concentration measurement.

RESULTS

Patient Disposition and Demographics

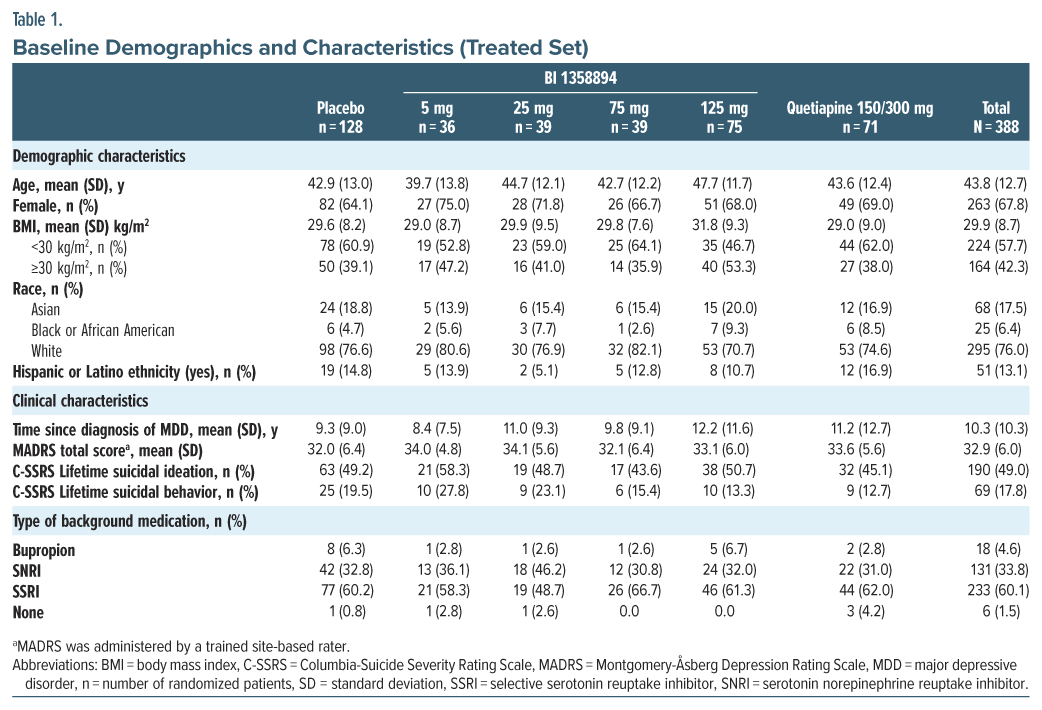

Of the 940 enrolled patients, 389 were randomized and 340 (87.6%) completed trial treatment. Of the 388 treated patients, 361 (93.0%) completed the trial, including 21 patients who remained in the trial following premature discontinuation of treatment. The patient disposition flowchart is presented in Supplementary Figure 2. Mean (standard deviation [SD]) age was 43.8 (12.7) years, mean (SD) body mass index was 29.9 (8.7) kg/m2, and 263 (67.8%) were female. Most patients were White (76.0%), had moderate-to-severe depression (mean [SD] MADRS total score was 32.9 [6.0]), and had a long disease history (mean [SD] time since diagnosis of MDD was 10.3 [10.3] years). Overall, 60.1% of patients were taking background SSRI, 33.8% were taking SNRI, and 4.6% were taking bupropion (Table 1). Use of SSRI/SNRI or bupropion was confirmed by serum testing in 382 (98.5%) patients at baseline and 315 (81.2%) patients at end of treatment. Medication adherence results are included in the Supplementary Materials.

Efficacy

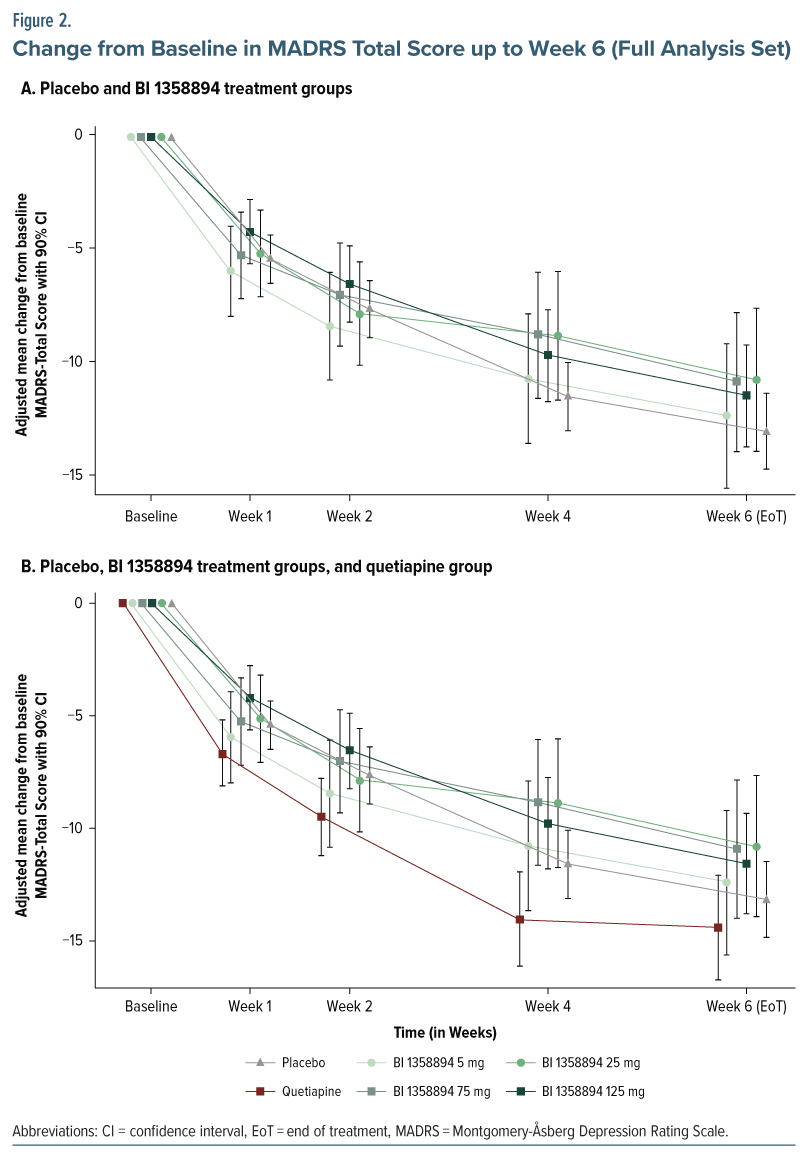

Primary end point. BI 1358894 failed to separate from placebo in the change from baseline in MADRS total score at any dose level or time point (Figure 2A; Supplementary Table 1). None of the models investigated in the MCPMod analysis indicated a nonflat dose-response for BI 1358894 (P values were nonsignificant, ie, exceeded 0.85 for all models); therefore, PoC could not be established (Supplementary Table 2). Further, the subgroup analyses did not reveal any differences between the BI 1358894 treatment groups and placebo. The change from baseline in MADRS total score in the quetiapine group showed a small numerical increase compared to placebo and BI 1358894 at all time points (Figure 2B; Supplementary Table 3).

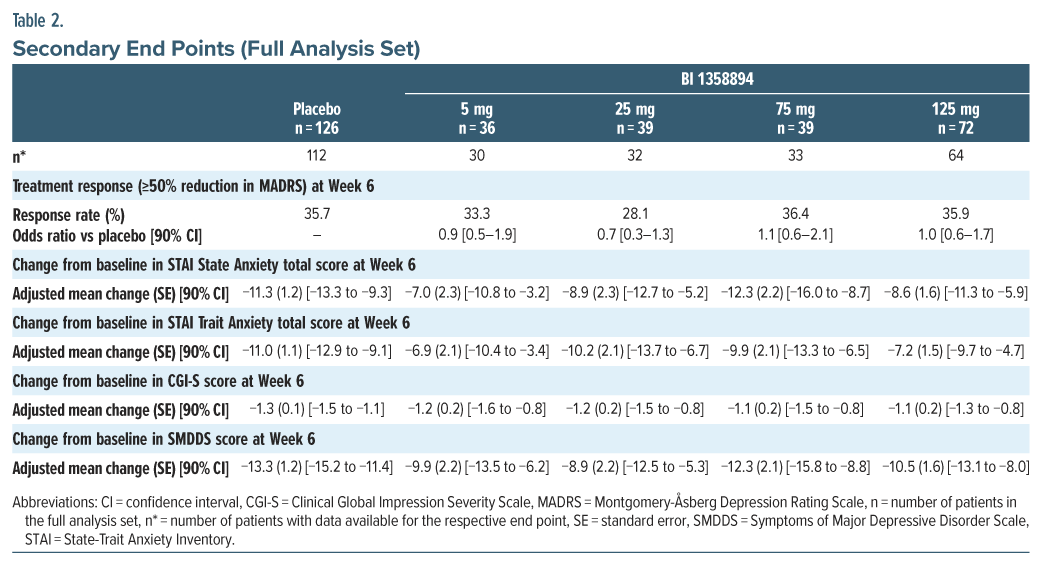

Secondary end points. The treatment response rate (≥50% reduction in MADRS) for patients did not differentiate from placebo in any of the BI 1358894 treatment groups. The mean reductions from baseline in STAI, CGI-S, and SMDDS scores were also similar between the BI 1358894 treatment groups and placebo over the duration of treatment, with no significant differences (Table 2). The descriptive results of change from baseline in STAI, CGI-S, and SMDDS scores at Week 6 were similar in the quetiapine and placebo groups (Supplementary Table 3).

Exploratory end points. BI 1358894 plasma concentrations increased with increasing dose. Steady state was reached after 2 weeks and was retained until the end of treatment at Week 6 in all BI 1358894 treatment groups (Supplementary 6 Figure 3). Additionally, there was no correlation between plasma concentration of BI 1358894 and change from baseline in MADRS total score at any dose level (Supplementary Figure 4).

There were no significant differences between the BI 1358894 treatment groups and placebo for any of the other exploratory end points (data not shown).

Safety

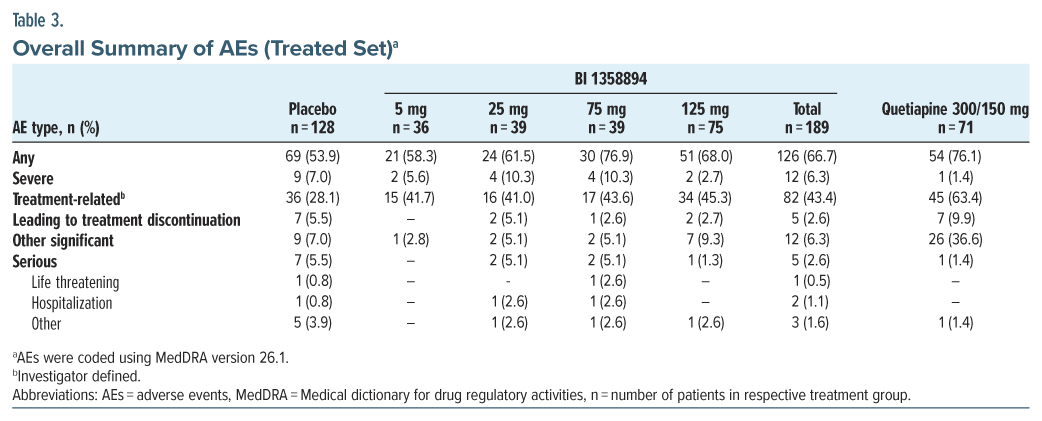

Overall, AEs were reported in all treatment groups, most frequently in the BI 1358894 75 mg group (76.9%), followed by the quetiapine (76.1%) and placebo (53.9%) groups (Table 3). AEs leading to trial medication discontinuation were most frequently reported in the quetiapine group (9.9%) followed by the placebo group (5.5%) while the frequency was lower in the BI 1358894-total group (2.6%; Supplementary Table 4).

The most frequently reported AEs (incidence of ≥5%) in the BI 1358894-total treated group vs placebo were headache (15.9% vs. 10.2%), dizziness (7.4% vs 2.3%), and somnolence (7.4% vs 3.1%). Extrapyramidal motor AEs were reported in 8 (4.2%) patients in the BI 1358894 total group, 4 (5.6%) patients in the quetiapine group, and 1 (0.8%) patient in the placebo group. The most common SAE, suicidal ideation, was reported in 6 (4.7%) patients in the placebo group, 2 (5.1%) patients in the BI 1358894 75 mg group, and 1 (1.4%) patient in the quetiapine group. No pattern of events was observed in the BI 1358894-treated groups, and no dose-dependent trend was seen in SAEs in BI 1358894-treated groups. There were no AESI and no deaths in any group. There were no clinically relevant changes from baseline for vital signs, 12-lead ECG, or any safety laboratory parameters during the trial. Overall, there was no worsening of C-SSRS scores over time for most patients, and suicidal ideation and behavior reported at any time on-treatment were infrequent. There were no completed suicides during the trial (Supplementary Table 5).

DISCUSSION

This phase 2 trial evaluated the efficacy and safety of 6 weeks of adjunctive BI 1358894 treatment vs placebo in patients with moderate-to-severe MDD receiving an ongoing antidepressant treatment. The trial failed to meet the primary and secondary end points as there were no significant differences between treatment groups and placebo, including the subgroup analyses. As PoC was not established, the dose-response modeling was not conducted. While this trial was not powered for statistical comparisons between the quetiapine and placebo or BI 1358894 treatment groups, the exploratory post hoc analysis of the primary end point, including the quetiapine arm, suggested a potential trend of antidepressant efficacy for quetiapine.

BI 1358894 was well tolerated, with the majority of events being nonserious and no pattern of serious events and drug discontinuations; therefore, the safety profile was consistent with the previous phase 1 trials in healthy volunteers.20–22 AEs leading to treatment discontinuation were less frequent in the BI 1358894- total treatment group (2.6%) than in the placebo (5.5%) or quetiapine treatment groups (9.9%). There were no completed suicides or increases in suicidal ideation or behavior while on treatment with BI 1358894, reflecting prior findings from a phase 2 decentralized clinical trial (DCT) in patients with MDD28 and a phase 2 trial in patients with borderline personality disorder.29

While BI 1358894 demonstrated reduced activation in corticolimbic regions including the amygdala in a previous functional magnetic resonance imaging phase 1b trial in patients with MDD,19 it did not demonstrate efficacy in the current phase 2 trial. This discrepancy between these trial results may be attributed to various factors. First, the neuroimaging biomarkers, such as reduced corticolimbic activation observed in the phase 1b trial, may not necessarily correlate with clinical outcomes or reliably predict clinical response. Second, the phase 1b trial included people with mild MDD (mean baseline MADRS total score of 17.7 in the BI 1358894 group) who were not receiving antidepressant treatment. In contrast, this PoC trial comprised patients with moderate-to-severe MDD (mean baseline MADRS total score ranged from 32.1 to 34.1 across BI 1358894 treatment groups). Third, the phase 1b trial had a small sample size of 73 participants (only 25 received BI 1358894), whereas in the present trial, 389 patients were randomized to receive treatment. The greater sample size and the large number of trial sites in 14 countries may have introduced heterogeneity. Lastly, the participants in the phase 1b trial received BI 1358894 monotherapy whereas in the present trial, patients were receiving BI 1358894 as an adjunctive treatment. These factors highlight the challenges of applying early-phase trial results to broader and more varied clinical populations.

The lack of positive efficacy results in the present trial is in alignment with a parallel phase 2 DCT with BI 1358894 in patients with MDD (terminated due to insufficient recruitment).28 However, there were notable differences between the patient population of the DCT and the present trial, ie, in terms of geographic recruitment (present trial, 14 countries; DCT, exclusively in US), sex (present trial, 67.8% females; DCT, 83.7% females), depression severity (mean baseline MADRS total score in present trial, 32.9; DCT, 26.6), and history of MDD (mean time since diagnosis of MDD in the present trial, 10.3 years; DCT, 15.5 years). Despite these differences, neither trial showed efficacy for BI 1358894 (5–125 mg) as an adjunctive treatment when administered daily over a 6-week period in the patient populations studied.

Despite the negative outcome, the trial had several strengths. This was a large, high-quality randomized controlled trial evaluating a novel treatment target and assessing 4 doses of BI 1358894 vs placebo plus an active control group for trial sensitivity. Notably, 93% of participants completed the trial, including those who discontinued treatment but remained in the study. A limitation of this study was its timing, as it commenced during the COVID-19 pandemic and may have impacted patient functionality and consequently their overall scores or participation in the trial.

In conclusion, this PoC trial evaluated the efficacy and safety of a 6-week treatment with BI 1358894 compared with placebo in patients with MDD with inadequate response to ongoing antidepressant pharmacotherapy. Although efficacy was not demonstrated in this trial, BI 1358894 was well tolerated and did not lead to an increase in self-harm or suicidality.

Article Information

Published Online: September 3, 2025. https://doi.org/10.4088/JCP.25m15868

© 2025 Physicians Postgraduate Press, Inc.

Submitted: March 6, 2025; accepted May 12, 2025.

To Cite: Shelton RC, Pizzagalli DA, Cohen EA, et al. Efficacy, tolerability, and safety of TRPC4/5 inhibitor BI 1358894 in patients with major depressive disorder and inadequate response to antidepressants: a phase 2 randomized, placebo-controlled, parallel group, dose-ranging trial. J Clin Psychiatry 2025;86(3):25m15868

Author Affiliations: Department of Psychiatry and Behavioral Neurobiology, University of Alabama at Birmingham, Birmingham, Alabama (Shelton); Center for Depression, Anxiety and Stress Research, McLean Hospital, Belmont, Massachusetts (Pizzagalli); Department of Psychiatry and Human Behavior and Department of Neurobiology and Behavior, University of California at Irvine, Irvine, California (Pizzagalli); CenExel Hassman Research Institute, Marlton, New Jersey (Cohen); Department of Psychiatry, Faculty of Medicine, Fukuoka University, Fukuoka, Japan (Hori); Biostatistics & Statistical Programming, Mainanalytics GmbH, Sulzbach/Taunus, Germany (Dickschat); Global Biostatistics & Data Sciences, Boehringer Ingelheim Pharmaceuticals, Inc, Ridgefield, Connecticut (Asafu-Adjei); Medical Safety, Boehringer Ingelheim Pharmaceuticals, Inc, Ridgefield, Connecticut (Feldbarg); Neuroscience & Mental Health, Boehringer Ingelheim Pharma GmbH & Co KG, Biberach an der Riss, Germany (Just); ClinOps Germany, Boehringer Ingelheim Pharma GmbH & Co KG, Biberach an der Riss, Germany (Roehrle); Global Regulatory Affairs, Boehringer Ingelheim International GmbH, Ingelheim am Rhein, Germany (Sommer); Therapeutic Area Mental Health, Boehringer Ingelheim International GmbH, Biberach an der Riss, Germany (Süssmuth).

Corresponding Author: Richard C. Shelton, MD, Department of Psychiatry and Behavioral Neurobiology, University of Alabama at Birmingham, 1720 2nd Ave South, Birmingham, AL 35294 ([email protected]).

Relevant Financial Relationships: Dr Shelton has received research support from NIH, Patient-Centered Outcomes Research Institute, Allergan, Plc, Alto Pharmaceuticals, Avanir Pharmaceuticals, Inc, Boehringer Ingelheim, Denovo Biopharma, Genomind, InMune Bio, Intra-cellular Therapies, Johnson & Johnson Innovative Medicines, LivaNova PLC, Navitor Pharmaceuticals, Neurocrine Biosciences, Nrx Pharmaceuticals, Novartis Pharmaceuticals, Otsuka Pharmaceutical Company, Sunovion Pharmaceuticals, Supernus Pharmaceuticals, Takeda Pharmaceuticals; he has served as a consultant for Acadia Pharmaceuticals, Boehringer Ingelheim, Cerecor, Inc, Denovo Biopharma, Johnson & Johnson Innovative Medicines, Nrx Pharmaceuticals, Novartis AG, Otsuka Pharmaceuticals, Seelos Therapeutics, Inc, Sunovion Pharmaceuticals, and Takeda Pharmaceuticals. Over the past 3 years, Dr. Pizzagalli has received consulting fees from Arrowhead. Pharmaceuticals, Boehringer Ingelheim, Compass Pathways, Engrail Therapeutics, Karla Therapeutics, Neumora Therapeutics (formerly BlackThorn Therapeutics), Neurocrine Biosciences, Neuroscience Software, Ono Pharmaceuticals, Sage Therapeutics, and Takeda; he has received honoraria from the American Psychological Association, Psychonomic Society and Springer (for editorial work) and Alkermes; he has received research funding from the Bird Foundation, Brain and Behavior Research Foundation, Dana Foundation, Millennium Pharmaceuticals, NIMH, and Wellcome Leap; he has received stock options from Ceretype Neuromedicine, Compass Pathways, Engrail Therapeutics, Neumora Therapeutics, and Neuroscience Software. Dr Pizzagalli served as a consultant to Boehringer Ingelheim for the randomized clinical trial presented in this manuscript. Dr Pizzagalli is publishing the current manuscript in a consulting capacity but did not receive compensation for the preparation of the current manuscript. Dr Pizzagalli is also a faculty member at Harvard Medical School and McLean Hospital. Dr Cohen is a Principal Investigator at CenExel Hassman Research Institute, an independent research site that conducts investigator-initiated and industry-sponsored pharmaceutical trials, including the study presented here. He has served as a consultant to Jazz Pharmaceuticals, Noven Pharmaceuticals, and Boehringer Ingelheim and has received grant/research support from Sunovion, Janssen, Cerevel, AbbVie, Alkermes, Allergan, Sage, Takeda, Otsuka, Neurocrine, Karuna, BioXcel, Xenon, IntraCellular, Lyndra, Boehringer Ingelheim, Pfizer/Viatris/Upjohn, Axsome, LB Pharmaceuticals, Minerva, Merck, Teva, and Denovo. Dr Hori has received speaker fees from Sumitomo Pharma, Otsuka, Meiji-Seika Pharma, MSD K.K., Pfizer, Janssen Pharmaceutical, Shionogi, and Takeda Pharmaceutical. Mrs Dickschat is a consultant with mainanalytics GmbH, Sulzbach/Taunus, Germany, which was contracted by Boehringer Ingelheim to assist with these analyses. Dr Just and Mr Roehrle are employees of Boehringer Ingelheim Pharma GmbH & Co KG. Drs Asafu-Adjei and Feldbarg are employees of Boehringer Ingelheim Pharmaceuticals, Inc. Drs Sommer and Süssmuth are employees of Boehringer Ingelheim International GmbH. Dr Süssmuth is also a member of the medical faculty of Ulm University, Germany, and declares no conflict of interest.

Funding/Support: This trial was funded by Boehringer Ingelheim International GmbH, Ingelheim am Rhein, Germany (BI trial number: 1402-0011; ClinicalTrials.gov identifier: NCT04521478).

Role of the Sponsor: Boehringer Ingelheim International GmbH contributed to the concept, study design, data collection, and analysis. The sponsor was given the opportunity to review the manuscript for medical and scientific accuracy as well as intellectual property considerations.

Acknowledgments: The authors thank the study patients for their participation in this study. Editorial support in the form of initial preparation of the outline based on input from all authors, and collation and incorporation of author feedback to develop subsequent drafts, assembling tables and figures, copyediting, and referencing was provided by Arshjyoti Singh, M. Pharm of Avalere Health Global Limited, and was funded by Boehringer Ingelheim International GmbH.

Data Availability Statement: To ensure independent interpretation of clinical study results and enable authors to fulfill their role and obligations under the ICMJE criteria, Boehringer Ingelheim grants all external authors access to clinical study data pertinent to the development of the publication. In adherence with the Boehringer Ingelheim Policy on Transparency and Publication of Clinical Study Data, scientific and medical researchers can request access to clinical study data when it becomes available on Vivli – Center for Global Clinical Research Data, and earliest after publication of the primary manuscript in a peer-reviewed journal, regulatory activities are complete, and other criteria are met. Please visit Medical & Clinical Trials | Clinical Research | MyStudyWindow for further information.

ORCID: Richard C. Shelton: https://orcid.org/0000-0002-3806-4208;

Diego A Pizzagalli: https://orcid.org/0000-0002-7772-1143;

Elan A. Cohen: https://orcid.org/0009-0009-6252-9130;

Ute Dickschat: https://orcid.org/0009-0006-9524-5888;

Josephine Asafu-Adjei: https://orcid.org/0009-0003-2846-6259;

Alla Feldbarg: https://orcid.org/0009-0006-7125-216X;

Stefan Just: https://orcid.org/0000-0001-9882-8110;

Michael Roehrle: https://orcid.org/0009-0002-4080-2078;

Stephanie Sommer: https://orcid.org/0009-0007-0057-2067;

Sigurd D. Süssmuth: https://orcid.org/0009-0008-9648-3831;

Hikaru Hori: https://orcid.org/0000-0001-8179-30540

Supplementary Material: Available at Psychiatrist.com.

Clinical Points

- Given the limitations of current treatments for major depressive disorder, there is an urgent need for new options. This study explores a new TRPC4/5 inhibitor, BI 1358894, as a potential alternative to existing add-on treatments.

- The trial did not demonstrate efficacy for BI 1358894, but the treatment was well tolerated with no observed increase in self-harm or suicidality.

References (29)

- Montano CB, Jackson WC, Vanacore D, et al. Considerations when selecting an antidepressant: a narrative review for primary care providers treating adults with depression. Postgrad Med J. 2023;135(5):449–465. PubMed CrossRef

- Rush AJ, Trivedi MH, Wisniewski SR, et al. Acute and longer-term outcomes in depressed outpatients requiring one or several treatment steps: a STAR*D report. Am J Psychiatry. 2006;163(11):1905–1917. PubMed CrossRef

- Ishak WW, Mirocha J, James D, et al. Quality of life in major depressive disorder before/after multiple steps of treatment and one-year follow-up. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 2015;131(1):51–60. PubMed CrossRef

- Bitter I, Szekeres G, Cai Q, et al. Mortality in patients with major depressive disorder: a nationwide population-based cohort study with 11-year follow-up. Eur Psychiatry. 2024;67(1):e63. PubMed CrossRef

- Chiu CC, Liu HC, Li WH, et al. Incidence, risk and protective factors for suicide mortality among patients with major depressive disorder. Asian J Psychiatr. 2023;80:103399. PubMed CrossRef

- Eriksson MD, Eriksson JG, Korhonen P, et al. Depressive symptoms and mortality-findings from Helsinki birth cohort study. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 2023;147(2):175–185. PubMed CrossRef

- Arnone D, Karmegam SR, Östlundh L, et al. Risk of suicidal behavior in patients with major depression and bipolar disorder – a systematic review and meta-analysis of registry-based studies. Neurosci Biobehav Rev. 2024;159:105594. PubMed CrossRef

- Buelt A, McQuaid JR. Comparing clinical guidelines for the management of major depressive disorder. Am Fam Physician. 2023;107(2):123–124. PubMed

- American Psychological Association. Clinical Practice Guideline for the Treatment of Depression Across Three Age Cohorts. American Psychological Association; 2019. Accessed November, 2024. https://www.apa.org/depression-guideline

- National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence (NICE) Guideline. Depression in Adults: Treatment and Management. National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence (NICE) guideline; 2022. Accessed November, 2024; https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/ng222

- Lam RW, Kennedy SH, Adams C, et al. Canadian Network for Mood and Anxiety Treatments (CANMAT) 2023 Update on Clinical Guidelines for Management of Major Depressive Disorder in Adults: réseau canadien pour les traitements de l’humeur et de l’anxiété (CANMAT) 2023 : mise à jour des lignes directrices cliniques pour la prise en charge du trouble dépressif majeur chez les adultes. Can J Psychiatry. 2024;69(9):641–687. PubMed CrossRef

- MacQueen G, Santaguida P, Keshavarz H, et al. Systematic review of clinical practice guidelines for failed antidepressant treatment response in major depressive disorder, dysthymia, and subthreshold depression in adults. Can J Psychiatry. 2017;62(1):11–23. PubMed CrossRef

- Kennedy SH, Lam RW, McIntyre RS, et al. Canadian Network for Mood and Anxiety Treatments (CANMAT) 2016 clinical guidelines for the management of adults with major depressive disorder: section 3. Pharmacological treatments. Can J Psychiatry. 2016;61(9):540–560. PubMed CrossRef

- Thase ME. Adverse effects of second-generation antipsychotics as adjuncts to antidepressants: are the risks worth the benefits? Psychiatr Clin N Am. 2016;39(3):477–486. PubMed CrossRef

- Wong JJ, Wong NML, Chang DHF, et al. Amygdala–pons connectivity is hyperactive and associated with symptom severity in depression. Commun Biol. 2022;5(1):574. PubMed CrossRef

- Li BJ, Friston K, Mody M, et al. A brain network model for depression: from symptom understanding to disease intervention. CNS Neurosci Ther. 2018;24(11):1004–1019. PubMed CrossRef

- Fowler MA, Sidiropoulou K, Ozkan ED, et al. Corticolimbic expression of TRPC4 and TRPC5 channels in the rodent brain. PLoS One. 2007;2(6):e573. PubMed CrossRef

- Riccio A, Medhurst AD, Mattei C, et al. mRNA distribution analysis of human TRPC family in CNS and peripheral tissues. Brain Res Mol Brain Res. 2002;109(1–2):95–104. PubMed CrossRef

- Grimm S, Keicher C, Paret C, et al. The effects of transient receptor potential cation channel inhibition by BI 1358894 on cortico-limbic brain reactivity to negative emotional stimuli in major depressive disorder. Eur Neuropsychopharmacol. 2022;65:44–51. PubMed CrossRef

- Goettel M, Fuertig R, Mack SR, et al. Effect of BI 1358894 on cholecystokinin-tetrapeptide (CCK-4)-induced anxiety, panic symptoms, and stress biomarkers: a phase I randomized trial in healthy males. CNS Drugs. 2023;37(12):1099–1109. PubMed CrossRef

- Fuertig R, Goettel M, Herich L, et al. Effects of single and multiple ascending doses of BI 1358894 in healthy male volunteers on safety, tolerability and pharmacokinetics: two phase I partially randomised studies. CNS Drugs. 2023;37(12):1081–1097. PubMed CrossRef

- Yoon J, Sharma V, Harada A. Safety, tolerability, and pharmacokinetics of oral BI 1358894 in healthy Japanese male volunteers. Clin Drug Investig. 2024;44(5):319–328. PubMed CrossRef

- Grimm S, Just S, Fuertig R, et al. TRPC4/5 inhibitors: phase I results and proof of concept studies. Eur Arch Psychiatry Clin Neurosci. 2024. doi:10.1007/s00406- 024-01890-0. CrossRef

- Montgomery SA, Asberg M. A new depression scale designed to be sensitive to change. Br J Psychiatry. 1979;134(4):382–389. PubMed CrossRef

- Spielberger CD, Gorsuch RL, Lushene R, et al. Manual for the State-Trait Anxiety Inventory. Consulting Psychologists Press; 1983.

- Guy W. ECDEU Assessment Manual for Psychopharmacology (Publication No. ADM 76–338): U.S. Department of Health, Education, and Welfare, Public Health Service, Alcohol, Drug Abuse, and Mental Health Administration. National Institute of Mental Health; 1976.

- Bushnell DM, McCarrier KP, Bush EN, et al. Symptoms of major depressive disorder Scale: performance of a novel patient-reported symptom measure. Value Health. 2019;22(8):906–915. PubMed CrossRef

- Reist C, Li P, Le Nguyen T, et al. Safety of BI 1358894 in patients with major depressive disorder: results and learnings from a phase II randomized decentralized clinical trial. Clin Transl Sci. 2024;17(12):e70102. PubMed CrossRef

- Dwyer J, Schmahl C, Makinodan M, et al. Efficacy and safety of BI 1358894 in patients with borderline personality disorder: results of a phase 2 randomized, placebo-controlled, parallel group dose-ranging trial. J Clin Psychiatry. 2025;86(1):24m15523. PubMed CrossRef

This PDF is free for all visitors!