Individuals at clinical high risk for psychosis (CHR-p) are a heterogeneous behavioral endophenotype that includes attenuated positive symptoms and decreased function that predicts higher rates of psychosis, among other disorders.1 Relatedly, early interventions for the CHR-p endophenotype with a narrow benefit to specific mechanisms of psychosis may not be appropriate.2 Instead, early interventions for CHR-p should focus on benefits for general symptoms.3 General symptoms are nonspecific neuropsychiatric symptoms that may result from CHR-p status, including sleep disturbance, dysphoric mood, motor disturbance, and stress tolerance.4–7 Exercise has broad benefits for general symptoms, including improving sleep quality, elevating mood, improving motor control, and increasing stress tolerance, broadening the benefits of intervention and suggesting potential transdiagnostic benefit.8–10 Despite this potential, exercise interventions have focused on the engagement of a particular mechanistic pathway to target the distinguishing symptoms of psychosis, including neuroprotective hippocampal, cognitive, and core symptoms pathways.11–14 It remains unknown if exercise benefits general symptoms or if general symptoms reduce as core symptoms abate.

Methods

The current analyses build on an exercise intervention (ClinicalTrials.gov identifier: NCT02155699; August 2018 to November 2021) that included high-impact treadmill interval training. This intervention consisted of participants beginning moderate progressing to intense aerobic exercise (twice weekly for 3 months) with sessions designed to elicit 80% VO2max for the majority of the time with 1-minute high-intensity intervals at 95% of VO2max every 10 minutes for 3 repetitions, for a total of 30 minutes.11 This study found that exercise improved hippocampal connectivity and working memory performance and attenuated positive symptoms of psychosis, and it added exploratory analyses of benefits for general symptoms.11 All neuroimaging and clinical staff were independent of the intervention and remained blinded. Inclusion criteria included the presence of an attenuated psychosis syndrome15 and a current sedentary lifestyle (<60-min exercise per week for 6 months). Exclusion criteria included current psychosis, antipsychotic prescription, or a substance use disorder. All participants were randomly assigned to intervention conditions with a balance for gender. They completed 2 assessments (before assignment and postintervention)11 for a full description of the protocol and subject demographics.14 The final sample included 17 exercise and 13 waitlist subjects. Analyses first examine changes within individuals before and after exercise; significant changes will be related to changes in core symptoms to investigate whether the change is proportional to core symptom change or relatively independent.

Results

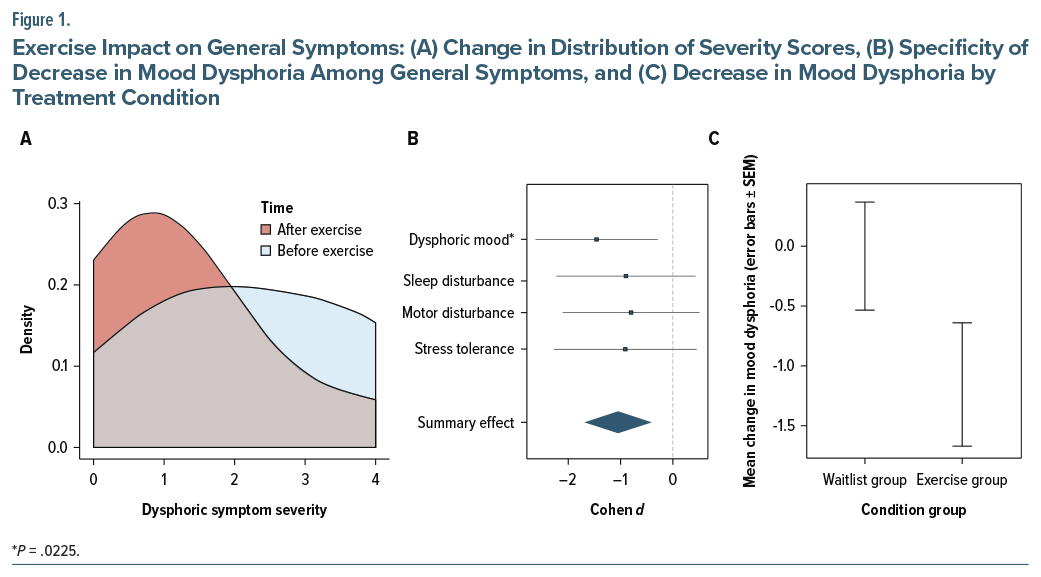

A mixed-effects model approach was used that accounted for individual effects as random effects, and the fixed effects of age, sex, and body mass index were nested within time (pretrial, posttrial) to predict each general symptom (sleep disturbance, dysphoric mood, motor disturbance, stress tolerance as measured by the Structured Interview for Psychosis Risk Syndromes) in separate models with Satterthwaite correction. Dysphoric mood was significantly reduced after the exercise intervention (t17=–2.43, b=−0.588 95% CI [−1.02, −0.156], P=.0225, d=−0.76 [−1.46, −0.06]) (Figure 1A). There were no other significant changes in other general symptoms (P >.5) (Figure 1B). Waitlist individuals did not show a change in mood dysphoria in the same period (P =.82) (Figure 1C). Follow-up analyses were conducted to examine a group-by-time interaction (t32=1.85, P=.07). Changes in mood dysphoria symptoms remained significant even when accounting for previously reported changes (positive symptoms, working memory, and hippocampal features) and were not significantly related to these variables (r’s<.02, P’s>.93).

Discussion

Although caution is needed when interpreting this specificity, mood dysphoria may reflect a distinct benefit of exercise that may occur along distinct mechanistic pathways, eg, decreased inflammation, increased endorphins,16 as there is no evidence of a relationship to change in core symptoms.

Limitations include that the current exercise protocol may not be optimized to elicit changes in sleep quality, motor disturbance, or stress tolerance. Additionally, general symptom ranges may be limited because they are being assessed clinically rather than objectively,17 and the sample was enriched for positive symptom severity rather than general symptom severity. Additionally, a small sample size may reduce power to detect a group-by-time interaction, warranting caution when generalizing these findings. Nevertheless, these findings encourage the consideration of early interventions that may benefit both core symptoms and general symptoms with the potential to also reduce alternative conversions, eg, depression.

Article Information

Published Online: January 7, 2026. https://doi.org/10.4088/JCP.25br16079

© 2026 Physicians Postgraduate Press, Inc.

J Clin Psychiatry 2026;87(1):25br16079

Submitted: September 8, 2025; accepted November 19, 2025.

To Cite: Damme KSF, Mittal VA. Exercise reduces dysphoria in clinical high risk for psychosis: a randomized controlled trial. J Clin Psychiatry 2026;87(1):25br16079.

Author Affiliations: Department of Psychology, School of Behavioral and Brain Sciences, University of Texas at Dallas, Richardson, Texas (Damme); Center for Vital Longevity, University of Texas at Dallas, Dallas, Texas (Damme); Center for Brain Health, University of Texas at Dallas, Dallas, Texas (Damme); Department of Psychology, Northwestern University, Evanston, Illinois (Mittal); Institute for Innovations in Developmental Sciences (DevSci), Northwestern University, Evanston and Chicago, Illinois (Mittal); Department of Psychiatry, Northwestern University, Chicago, Illinois (Mittal); Medical Social Sciences, Northwestern University, Chicago, Illinois (Mittal); Institute for Policy Research (IPR), Northwestern University, Chicago, Illinois (Mittal).

Corresponding Author: Katherine S. F. Damme, PhD, Department of Psychology, School of Brain and Behavioral Sciences, University of Texas at Dallas, 800 W Campbell Rd, Richardson, TX 75080 ([email protected]).

Relevant Financial Relationships: The authors have no conflicts to disclose.

Funding/Support: This work was supported by the National Institute of Mental Health (R21/R33MH103231 to Dr Mittal and R21MH136408 to Drs Damme and Mittal).

Role of the Sponsor: Feedback on planned protocol and analyses prior to data collection through the peer review process only.

References (17)

- Lee TY, Lee H, Lee J, et al. The characteristics and clinical outcomes of a pluripotent high-risk group with the potential to develop a diverse range of psychiatric disorders. J Psychiatr Res. 2024;174:237–244. PubMed CrossRef

- Damme KSF, Mittal VA. Managing clinical heterogeneity in psychopathology: perspectives from brain research. J Psychopathol Clin Sci. 2024;133(8):599–604. PubMed CrossRef

- Hitchcock PF. Of strong swords and fine scalpels: developing robust clinical principles to cut through heterogeneity. J Psychopathol Clin Sci. 2024;133(8):605–608. PubMed CrossRef

- Damme KSF, Vargas TG, Walther S, et al. Physical and mental health in adolescence: novel insights from a transdiagnostic examination of FitBit data in the ABCD study. Transl Psychiatry. 2024;14(1):75. PubMed CrossRef

- Banno M, Harada Y, Taniguchi M, et al. Exercise can improve sleep quality: a systematic review and meta-analysis. PeerJ. 2018;6:e5172. PubMed CrossRef

- Martínez-Díaz IC, Carrasco L. Neurophysiological stress response and mood changes induced by high-intensity interval training: a pilot study. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2021;18(14):7320. PubMed

- Wilke J, Mohr L. Chronic effects of high-intensity functional training on motor function: a systematic review with multilevel meta-analysis. Sci Rep. 2020;10(1):21680. PubMed CrossRef

- Firth J, Schuch F, Mittal VA. Using exercise to protect physical and mental health in youth at risk for psychosis. Res Psychother. 2020;23(1):433. PubMed CrossRef

- Acil AA, Dogan S, Dogan O. The effects of physical exercises to mental state and quality of life in patients with schizophrenia. J Psychiatr Ment Health Nurs. 2008;15(10):808–815. PubMed CrossRef

- Dauwan M, Begemann MJH, Heringa SM, et al. Exercise improves clinical symptoms, quality of life, global functioning, and depression in schizophrenia: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Schizophr Bull. 2016;42(3):588–599. PubMed CrossRef

- Damme KSF, Gupta T, Ristanovic I, et al. Exercise intervention in individuals at clinical high risk for psychosis: benefits to fitness, symptoms, hippocampal volumes, and functional connectivity. Schizophr Bull. 2022;48(6):1394–1405. PubMed CrossRef

- Firth J, Stubbs B, Vancampfort D, et al. Effect of aerobic exercise on hippocampal volume in humans: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Neuroimage. 2018;166:230–238. PubMed CrossRef

- Kimhy D, Vakhrusheva J, Bartels MN, et al. The impact of aerobic exercise on brain-derived neurotrophic factor and neurocognition in individuals with schizophrenia: a single-blind, randomized clinical trial. Schizophr Bull. 2015;41(4):859–868. PubMed CrossRef

- Firth J, Stubbs B, Rosenbaum S, et al. Aerobic exercise improves cognitive functioning in people with schizophrenia: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Schizophr Bull. 2017;43(3):546–556. PubMed CrossRef

- Miller TJ, McGlashan TH, Rosen JL, et al. Prodromal assessment with the structured interview for prodromal syndromes and the scale of prodromal symptoms: predictive validity, interrater reliability, and training to reliability. Schizophr Bull. 2003;29(4):703–715. PubMed CrossRef

- Mittal VA, Vargas T, Osborne KJ, et al. Exercise treatments for psychosis: a review. Curr Treat Options Psych. 2017;4(2):152–166. PubMed CrossRef

- Damme KSF, Sloan RP, Bartels MN, et al. Psychosis risk individuals show poor fitness and discrepancies with objective and subjective measures. Sci Rep. 2021;11(1):9851. PubMed CrossRef

This PDF is free for all visitors!