Abstract

Functional recovery has emerged as a critical treatment goal in schizophrenia, extending beyond symptom reduction to encompass independent living, vocational and educational attainment, social integration, and overall quality of life. Despite advances in pharmacotherapy, many people with schizophrenia continue to experience significant functional impairments driven by persistent symptoms, cognitive deficits, comorbidities, stigma, and adverse social determinants. Psychosocial interventions have been shown to be effective in improving functional outcomes but are not extensively utilized. To address these challenges, a consensus panel of experts in psychiatry and psychology reviewed the evidence base and developed practical recommendations for optimizing functional outcomes.

Panel discussions highlighted 4 domains of functional drivers in schizophrenia: intrinsic, behavioral, comorbid/consequential, and societal/contextual, and evaluated psychosocial interventions with demonstrated benefits relative to these domains. Amidst lingering questions about further refinement and optimal individualization, evidence clearly supports the use of cognitive behavioral therapy, cognitive remediation, social skills training, supported employment and housing, and family-focused interventions; likewise, evidence supports the use of psychoeducation, motivational interviewing, mindfulness- and acceptance-based therapies, and lifestyle interventions, such as structured exercise. Implementation remains limited due to workforce shortages, resource constraints, and a lack of integration into routine care.

The panel recommends a comprehensive, patient-centered approach that integrates pharmacological treatment with evidence-based psychosocial strategies, guided by measurement-based care and individualized treatment planning. Validated functional assessment tools and emerging digital therapeutics offer scalable methods to monitor and enhance outcomes. By addressing both intrinsic and extrinsic drivers of disability, clinicians can more effectively support people with schizophrenia in achieving functional recovery and an improved quality of life.

J Clin Psychiatry 2025;86(4):hfrecachi2505

Watch the three-part video series: Part 1 | Part 2 | Part 3

This Academic Highlights section of The Journal of Clinical Psychiatry presents the highlights of the virtual consensus panel meeting “Psychosocial Interventions and Functional Recovery in Schizophrenia—Realizing Opportunities Today,” which was held June 2, 2025.

The meeting was chaired by Rajiv Tandon, MBBS, MD, MS, Western Michigan University Homer Stryker MD School of Medicine, Kalamazoo, Michigan (correspondence: [email protected]; 211 Langley Road, Newton, MA 02459). The faculty were Deanna M. Barch, PhD, Washington University, Saint Louis, Missouri; Robert W. Buchanan, MD, University of Maryland School of Medicine, Baltimore, Maryland; Michael F. Green, PhD, University of California, Los Angeles, California; Matcheri S. Keshavan, MD, Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center, Boston, Massachusetts; Stephen R. Marder, MD, University of California, Los Angeles, California; Henry A. Nasrallah, MD, University of Cincinnati Neuroscience Institute, Cincinnati, Ohio; and Antonio Vita, MD, PhD, University of Brescia, Brescia, Italy.

Financial disclosures appear at the end of the article.

This evidence-based, peer-reviewed Academic Highlights article was prepared by Healthcare Global Village, Inc. The consensus panel meeting on which this manuscript is based was funded by Boehringer-Ingelheim Pharmaceuticals, Inc., Ridgefield, Connecticut. The sponsor had no role in the writing, review, or submission of this manuscript. The authors, with support from Healthcare Global Village, Inc., drafted and submitted the article for peer review. Article processing charges, medical writing, editorial, and other assistance were funded by Healthcare Global Village, Inc. Editorial support was provided by P. Benjamin Everett, PhD, Healthcare Global Village, Inc. The opinions expressed herein are those of the faculty and do not necessarily reflect the views of Healthcare Global Village, Inc., the publisher, or the commercial sponsor. This article is distributed by Healthcare Global Village, Inc. for educational purposes only.

Published Online: December 17, 2025.

To Cite: Tandon R, Barch DM, Buchanan RW, et al. Psychosocial interventions and functional recovery in schizophrenia—realizing opportunities today. J Clin Psychiatry. 2025;86(4):JCP.hfrecachi2505

To Share: https://doi.org/10.4088/JCP.hfrecachi2505

© 2025 Physicians Postgraduate Press, Inc.

Introduction

Schizophrenia is a lifelong condition and a leading cause of global disability, imposing substantial health, social, and financial burdens on individuals, caregivers, and systems of care.1–3 Schizophrenia presents with a spectrum of positive symptoms, negative symptoms, and cognitive impairments.4–10 The primary treatment goal in schizophrenia is to enable recovery, broadly defined as the ability of an individual with schizophrenia to lead a productive and personally meaningful life.11,12 The objective of treatment is to optimally facilitate the individual’s ability to do so in the face of living with schizophrenia. To accomplish this, we need to develop individualized, patient-centered care that adapts across the illness spectrum (first episode vs multi-episode).

Pharmacological treatment remains the foundation of management, but it is limited by incomplete symptom control, adverse effects, and nonadherence.7,10–14 Accordingly, evidence-based psychosocial and rehabilitation interventions are essential to comprehensive care.13,14 Yet, functional outcomes remain poor for myriad reasons, including modest effect sizes of currently available psychosocial tools; underutilization of psychosocial tools due to limited access, workforce shortages, training gaps, and systemic underinvestment; and clinical inertia fostered by low expectations and therapeutic nihilism.15–18 Closing this gap requires renewed emphasis on individualized, measurement-based care that addresses all symptom domains and the broader determinants of functional recovery.19,20

In June 2025, a multidisciplinary panel of 8 experts in psychiatry, psychology, and psychosocial research was convened to evaluate key drivers of functional impairment and to review psychosocial and psychotherapeutic interventions that promote functional recovery. Through structured discussions, the panel integrated evidence and clinical expertise to identify functional drivers, align interventions with targeted domains, and develop consensus-based recommendations for optimizing care delivery.

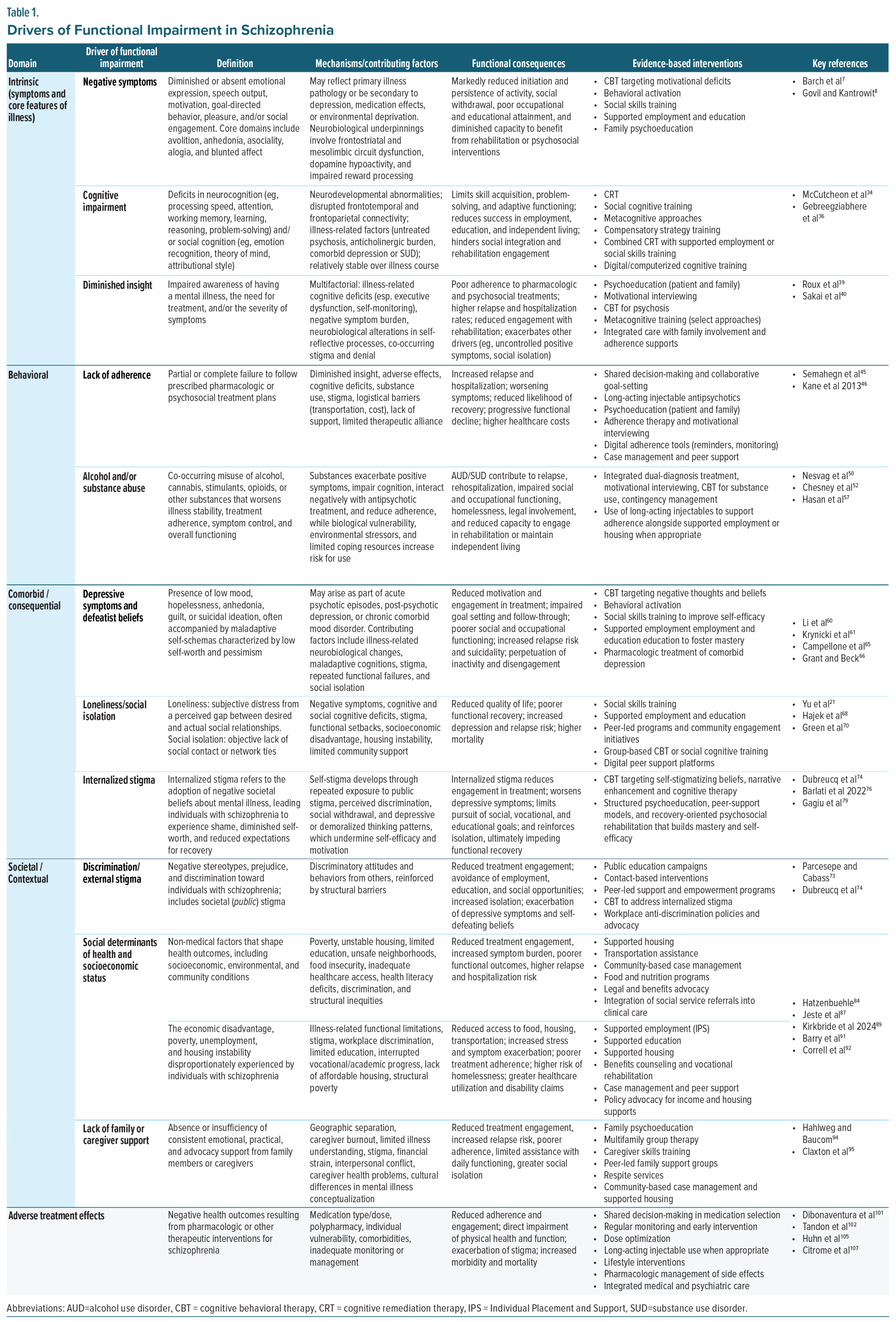

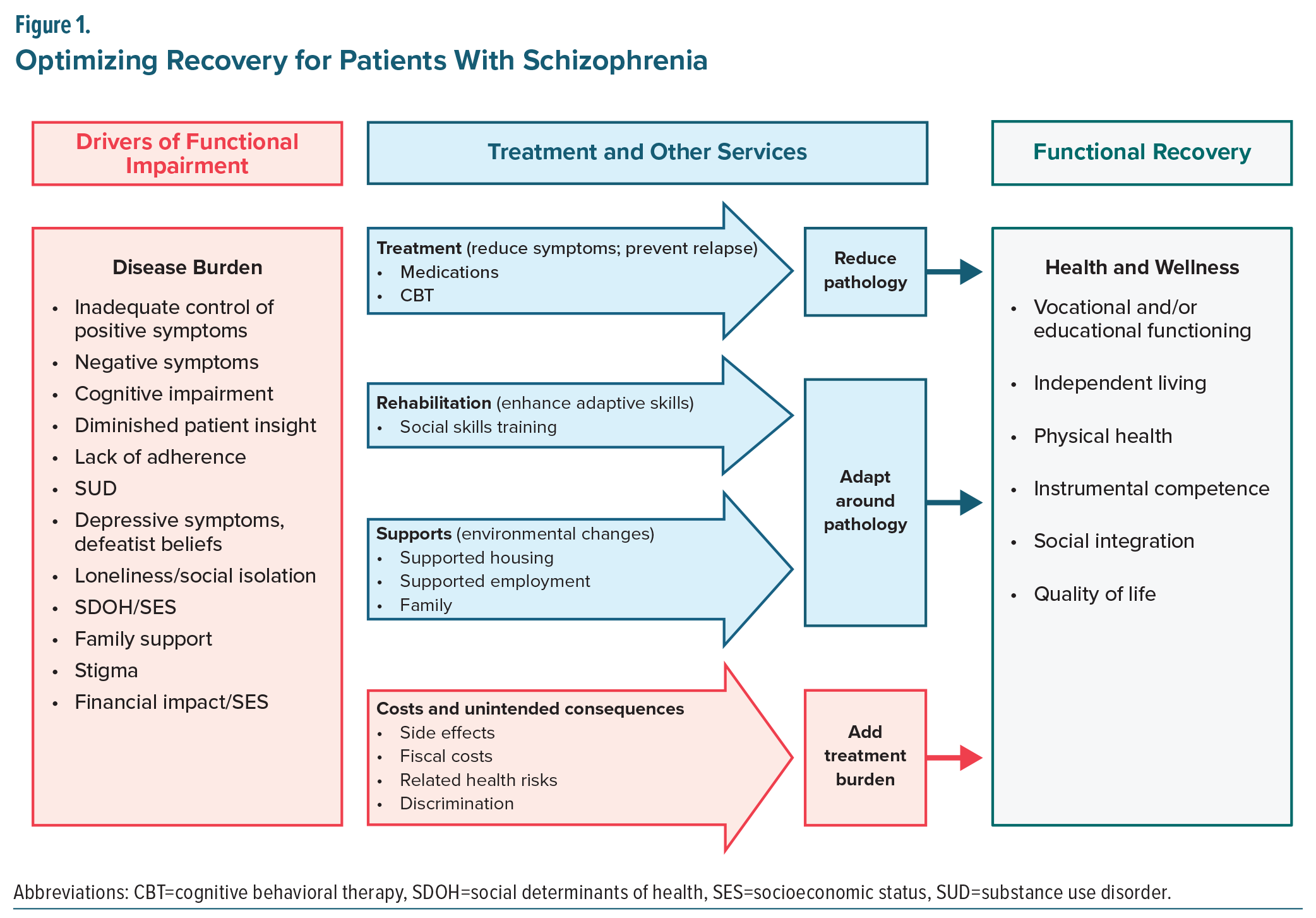

To guide this effort, the panel adopted a framework, which categorized drivers of impairment into 4 domains: intrinsic, behavioral, comorbid/consequential, and societal/contextual (Table 1). These domains served as the foundation for evaluating how different psychosocial interventions may target distinct contributors to functional disability. Figure 1 illustrates this functional framework, highlighting how pharmacological treatment, rehabilitation strategies, and supportive services may act independently, additively, or potentially synergistically, to reduce burden and enhance recovery. The figure also acknowledges that all interventions carry inherent costs or burdens that may offset gains. The sections that follow revisit this model in depth, elaborating on how it informs the selection and integration of psychosocial interventions across functional domains. Of note, systemic barriers were also discussed as drivers of disability and are discussed briefly; however, as these barriers are not directly related to the underlying disease pathology, they are discussed separately.

Methods

In June 2025, a multidisciplinary panel was convened to evaluate key drivers of functional impairment in persons with schizophrenia, encompassing psychopathological, individual, societal, and treatment-related factors. The panel was chaired by Rajiv Tandon, MD. Panelists included Deanna M. Barch, PhD; Robert W. Buchanan, MD; Michael F. Green, PhD; Matcheri S. Keshavan, MD; Stephen R. Marder, MD; Henry A. Nasrallah, MD; and Antonio Vita, MD, PhD.

The panel met virtually in a structured, facilitated discussion designed to balance review of the published evidence with expert interpretation and clinical experience. Panelists considered determinants of functional outcome across psychopathological, individual, societal, and treatment-related domains and discussed how these factors interact over the illness course. In addition to analyzing publicly available clinical trial and meta-analytic data, panelists shared their own perspectives on the utility, mechanisms of action, and implementation barriers of psychosocial and psychotherapeutic interventions.

The agenda included (1) identification and categorization of drivers of functional impairment; (2) review of psychosocial interventions; (3) evaluation of validated tools and measurement-based care strategies; and (4) consideration of emerging digital interventions and their potential to enhance scalability.

Consensus was reached through iterative discussion, with a focus on aligning evidence with real-world practice and on generating practical, patient-centered recommendations. This Academic Highlights presents the consensus findings of the panel and is based on review of published literature and clinical experience; it is not intended to represent a systematic review or meta-analysis.

Consensus Statement #1

“Functional outcomes in schizophrenia remain far below what is achievable due to systemic underutilization of evidence-based psychosocial interventions. Despite their demonstrated impact, these tools are often inaccessible, unsupported, or overlooked, reinforcing a culture of therapeutic nihilism.”

Drivers of Functional Impairment in Schizophrenia

Understanding the drivers of functional impairment in schizophrenia is essential for guiding pharmacological and psychosocial strategies. Based on faculty feedback and panel consensus, these drivers can be grouped into 4 core categories reflecting factors intrinsic to the disorder and its consequences: intrinsic, behavioral, comorbid/consequential, and societal/contextual. Treatment-related factors and systemic barriers, while important contributors to functional outcomes, were distinguished as separate because they do not arise from the underlying pathophysiology of schizophrenia itself (Table 1).

Intrinsic drivers arise from core illness features, such as positive and negative symptoms, cognitive deficits, and diminished insight; internalized- or self-stigma is included here as well. Behavioral drivers reflect behaviors that interfere with functioning, including nonadherence to medication or appointments and co-occurring substance or alcohol use disorders. Comorbid and consequential drivers include conditions that frequently co-occur with or result from schizophrenia, such as depressive symptoms and physical comorbidities, defeatist beliefs, and loneliness or social isolation. Societal and contextual drivers encompass environmental and systemic factors, including external stigma/discrimination, poverty, and other adverse social determinants of health. Finally, treatment-related drivers stem from the care process itself, such as medication adverse effects and the complexity or burden of treatment regimens. These domains often interact; for example, cognitive impairment (intrinsic) can hinder social participation, fostering isolation (comorbid/consequential), which in turn exacerbates symptoms and reduces functioning.21,22 Likewise, discrimination in employment (societal/contextual) can worsen financial instability, increasing stress and undermining illness self-management (intrinsic).23

The section that follows addresses each of these domains in turn, highlighting their contribution to functional impairment and opportunities for intervention. This section provides a framework for understanding these drivers, which will be linked in subsequent sections to evidence-based interventions and practical guidance for integrating them into individualized, measurement-based care plans.18,24

Intrinsic Drivers of Functional Impairment

Intrinsic drivers stem from the illness itself and include the hallmark symptom domains of schizophrenia: positive, negative, and cognitive symptoms, as well as diminished insight. These features directly impair motivation, learning, decision-making, and social functioning, and often persist even when psychosis is well controlled. Because they are core illness features, intrinsic drivers represent some of the most persistent barriers to functional recovery.

Symptoms. While positive symptoms can significantly impact the daily functioning of the person with schizophrenia and their caregivers,25 and have negative impact on employment,23 negative symptoms are considered the larger driver of impairment in schizophrenia.7,8 Negative symptoms comprise a heterogeneous set of conditions with diverse etiologies, often requiring distinct treatment strategies.26 Five core domains of negative symptoms are recognized: blunted affect (reduced emotional expression), alogia (limited speech), asociality (reduced social interaction), anhedonia (diminished capacity for pleasure), and avolition (reduced motivation or goal-directed behavior).27

Negative symptoms impose a substantial burden on individuals, caregivers, and society, contributing to poor functional outcomes, increased unemployment, greater illness severity, and often higher antipsychotic dosages.27 There are substantial correlations among these 5 domains, with factor-analytic studies grouping the 5 classic negative symptoms into 2 domains, the first consisting of diminished emotional expression and including blunted affect and alogia and the second consisting of reduced motivation and pleasure and including avolition, anhedonia, and asociality.7,8,28

Cognitive impairment. Cognitive impairment is a core feature of schizophrenia, affecting most individuals with the disorder and often emerging during the prodrome before the onset of psychosis.24,29 Cognitive impairments are seen in both non-social cognition (eg, processing speed, attention, learning and memory, problem-solving, working memory) and social cognition (eg, emotion processing, social perception, attributional bias, mentalizing).30 These deficits are among the strongest predictors of poor functional outcomes, adversely affecting occupational performance, social relationships, and independent living skills.30 Meta-analyses show that cognitive deficits in schizophrenia are moderate to large in magnitude compared with healthy controls and are an enduring feature across the across the lifespan of the disorder, even when positive symptoms remit.31–33

These impairments stem from a combination of neurodevelopmental and neurodegenerative processes and illness-related factors such as untreated psychosis, anticholinergic burden, and comorbidities, such as depression and substance use.34–37 Functionally, cognitive deficits limit the acquisition and application of new skills, impair social problem-solving, and reduce the ability to adapt to environmental demands, thereby restricting success in employment, education, independent living, and social integration and collectively limiting an individual’s functional recovery.35,36

Diminished insight. Diminished insight is a prevalent and clinically significant driver of functional impairment in schizophrenia.38 It encompasses an impaired awareness of having an illness, misunderstanding of the need for treatment, and/or underestimation of symptom severity. Estimates suggest that poor insight occurs in approximately 50%–98% of individuals with schizophrenia, dependent on the stage of the illness, and is relatively independent of positive symptom remission.39–41

The origins of diminished insight are multifactorial, involving illness-related cognitive deficits, particularly in executive function and self-monitoring, negative symptom burden, and possible neurobiological changes affecting self-reflective processes.41–43

Functionally, diminished insight is linked to poorer adherence to pharmacological and psychosocial interventions, higher rates of relapse and hospitalization, and reduced engagement with rehabilitation services.

Behavioral Drivers of Functional Impairment

Behavioral drivers reflect actions and habits of people with schizophrenia that undermine recovery, most prominently nonadherence to treatment and substance or alcohol misuse. These behaviors can destabilize symptom control, increase relapse risk, and compound functional impairments. Addressing behavioral drivers often requires tailored interventions to improve treatment engagement and reduce the impact of co-occurring substance use disorders.

Lack of adherence (to medication and appointments). Nonadherence to prescribed pharmacological or psychosocial treatments is a major treatment-related driver of functional impairment in schizophrenia, with rates estimated at 40%–60% in community samples.44–47 Adherence challenges can be partial or complete and often fluctuate over time. Contributing factors include diminished insight, adverse treatment effects, cognitive impairment, substance use, stigma, and logistical barriers, such as transportation, cost, and lack of family or caregiver support.45–47

The consequences of nonadherence are substantial and can lead to increased relapse risk, more frequent hospitalizations, worsening of positive and negative symptoms, higher healthcare costs, and reduced likelihood of functional recovery. Repeated relapses can lead to progressive functional decline, greater treatment resistance, and erosion of social and occupational skills.48,49

Alcohol and substance use disorder. Alcohol and substance use disorders (AUDs/SUDs) are highly prevalent in individuals with schizophrenia, with lifetime comorbidity estimates ranging from 40%–60%.50–54 Commonly misused substances include alcohol, cannabis, stimulants, and nicotine, with cannabis use disorder showing a particularly strong association with earlier illness onset, more severe positive symptoms, and increased risk of relapse.55–57 The relationship between schizophrenia and SUD is bidirectional: substance use can exacerbate psychotic symptoms and functional decline, while illness-related factors, such as social isolation, impaired coping skills, and diminished insight, can increase vulnerability to substance misuse. Neurobiological factors, including dysregulation of reward system, may also contribute to this comorbidity.54,58,59

Functionally, AUDs/SUDs compound the burden of schizophrenia by impairing treatment adherence, increasing risk for hospitalization and homelessness, worsening cognitive and negative symptoms, and contributing to legal, interpersonal, and occupational problems. Substance use may also diminish the effectiveness of psychosocial interventions and reduce the likelihood of recovery-oriented goal attainment.58,59

Comorbid/Consequential Drivers of Functional Impairment

Comorbid and consequential drivers include psychiatric and medical conditions that co-occur with schizophrenia or emerge as sequelae of illness. Common examples are depressive symptoms, defeatist beliefs, loneliness, and social isolation, which add an additional burden to already impaired functioning. These conditions frequently interact with intrinsic symptoms, amplifying disability and complicating recovery trajectories.

Depressive symptoms and defeatist beliefs. Depressive symptoms frequently accompany various phases of schizophrenia and may resemble the negative symptoms of the disorder, with prevalence estimates ranging from 25%–50% during the course of illness.60–62 They may emerge during acute psychotic episodes or in the post-psychotic recovery phase, or persist as part of a chronic affective comorbidity.63 These symptoms include low mood, hopelessness, anhedonia, guilt, and suicidal ideation and are often intertwined with defeatist beliefs, such as negative self-schemas characterized by low self-worth, perceived incompetence, and pessimism about the future. Such beliefs can be reinforced by the illness experience itself, societal stigma, and repeated functional setbacks.64–66

Functionally, depressive symptoms and defeatist beliefs can undermine motivation, goal setting, and engagement with both pharmacological and psychosocial interventions.65,66 They are associated with poorer social and occupational outcomes, increased relapse risk, and higher suicide rates. Moreover, they can interact with other drivers of impairment, such as cognitive deficits and stigma, creating a reinforcing cycle of loneliness and social isolation.

Consensus Statement #2

“Functional impairment in schizophrenia arises from a constellation of intrinsic and behavioral, comorbid/consequential, societal/contextual drivers, and adverse treatment effects. These include neurocognitive deficits, behavioral and motivational impairments, comorbidities, and social determinants of health. Interventions must be targeted to specific drivers.”

Loneliness/social isolation. Loneliness and social isolation are common and debilitating experiences in schizophrenia that are distinct yet interrelated phenomena. Loneliness refers to the subjective distress stemming from a perceived gap between desired and actual social relationships, whereas social isolation describes the objective lack of social contact or network connections.21 Both are highly prevalent in people with schizophrenia, often beginning early in the illness course, and can persist despite effective management of positive symptoms.67,68 Qualitative research in early psychosis supports these findings and indicates that loneliness is frequently experienced although clinicians do not tend to explicitly inquire about it.69

Contributors to loneliness and social isolation include negative symptoms, such as avolition and asociality (ie, reduced social motivation), cognitive and social cognitive deficits, internal stigma, and functional setbacks that limit opportunities for meaningful interaction.70,71 Social isolation can be reinforced by socioeconomic disadvantage, housing instability, and limited access to community-based supports. The resulting lack of social engagement not only diminishes quality of life but also predicts poorer functional outcomes, increased depressive symptoms, higher relapse risk, and elevated mortality.70,72

Internalized stigma. Stigma remains a pervasive driver of functional impairment in schizophrenia, influencing both how individuals view themselves or internalize negative societal views about their group, ie, all individuals with schizophrenia (internalized- or self-stigma) and how they are perceived and treated by others (public or external stigma will be discussed under “Discrimination/external stigma”).73–75 Self-stigma involves the internalization of negative societal stereotypes, leading to diminished self-esteem, reduced hope, and reluctance to pursue personal or professional goals.74–76 Internalized stigma has been consistently associated with poorer adherence to treatment, reduced self-efficacy and occupational competence, and lower subjective quality of life and social functioning. It can also exacerbate cognitive dysfunction and limit insight into the disorder.76–80

Societal/Contextual Drivers of Functional Impairment

Societal and contextual drivers encompass interpersonal and environmental influences that shape opportunities for recovery. These include the presence or absence of supportive family or caregiver relationships, as well as external pressures, such as stigma, discrimination, poverty, and other adverse social determinants of health. By constraining opportunities for social integration and reinforcing illness-related challenges, these drivers often magnify the impact of intrinsic, behavioral, and comorbid factors.

Discrimination/external stigma. As noted previously, stigma remains a pervasive driver of functional impairment in schizophrenia. Public or external stigma relates to how individuals with schizophrenia are perceived and treated by others or society.73–75 Public stigma encompasses discriminatory attitudes and behaviors from employers, healthcare providers, community members, and even family, which can limit opportunities for employment, housing, education, and social participation.73

The effects of stigma are compounded by structural barriers, such as policies and institutional practices that disadvantage individuals with serious mental illness.81,82 Together, these forces can create a self-reinforcing cycle in which stigma limits participation, reduced participation fuels isolation, and isolation further entrenches both self- and public stigma.83,84

Social determinants of health. Social determinants of health (SDOH), the non-medical conditions in which people are born, grow, live, work, and age, exert a profound influence on outcomes for individuals with schizophrenia. Adverse SDOH such as poverty, unstable housing, limited educational opportunities, unsafe neighborhoods, food insecurity, and inadequate access to health care interact with illness-related impairments to hinder recovery.83 These factors reduce opportunities for treatment engagement, increase symptom burden, and constrain functional capacity.84–89

The effects of SDOH are cumulative and often mutually reinforcing. Housing instability disrupts continuity of care and medication adherence; unreliable transportation limits access to appointments, employment, and community supports; and low health literacy impairs the ability to navigate complex healthcare systems. For many individuals, particularly those in marginalized or under-resourced communities, structural racism, discrimination, and lack of culturally responsive care further compound these disadvantages.84,89,90

Within this broader framework, socioeconomic status represents a central and cross-cutting determinant. The financial and socioeconomic consequences of schizophrenia are substantial and extend beyond the individual to families and communities.3 People with schizophrenia experience disproportionately high rates of unemployment, poverty, and housing instability, reflecting the combined impact of limited educational attainment, workplace discrimination, and the episodic or chronic nature of the illness on vocational and academic trajectories. Low income and lack of affordable housing contribute to markedly elevated rates of homelessness.3,89

Socioeconomic disadvantage both results from and exacerbates illness-related impairments. Individuals with schizophrenia are significantly more likely to live in poverty than those without psychotic disorders, a disparity associated with more severe positive, negative, and cognitive symptoms and greater risk for suicidal behavior. Poverty restricts access to nutritious food, safe and stable housing, and transportation, while financial stress contributes to worsening psychiatric symptoms and reduced treatment adherence. At the systems level, the socioeconomic burden is reflected in high healthcare utilization, reliance on disability benefits, and lost productivity.90–92

Lack of family or caregiver support. Family and caregiver support is a critical extrinsic factor influencing recovery in schizophrenia. When present, it can facilitate treatment adherence, provide emotional and practical assistance, and create an environment that supports rehabilitation. Conversely, the absence of such support, or the presence of strained, conflict-laden, or overinvolved relationships, can hinder engagement with services, increase relapse risk, and exacerbate functional impairments.93–95

Contributors to insufficient family or caregiver support include geographic separation, caregiver burnout, limited understanding of schizophrenia, stigma, financial strain, and breakdowns in family relationships.94,96 In some cases, caregivers may themselves face health or mental health challenges, limiting their capacity to provide consistent help.97,98 Cultural differences in conceptualizing mental illness and recovery can also affect the type and quality of support offered.93,97,99

Treatment-Related Burden

Treatment-related drivers arise from the therapeutic process itself. Adverse effects of medications, anticholinergic burden, and the complexity of treatment regimens can diminish quality of life and create new functional barriers. If not managed proactively, these drivers can erode adherence and counteract the benefits of symptom control, limiting progress toward recovery.

Adverse effects from antipsychotic and adjunctive medications are a significant treatment-related driver of functional impairment in schizophrenia.45,100–102 These can include extrapyramidal symptoms, tardive dyskinesia, akathisia, sedation, weight gain, metabolic syndrome, hyperprolactinemia, and anticholinergic burden.103–107 Even when clinically manageable, these effects may reduce treatment satisfaction and adherence, impacting long-term symptom control and functional outcomes.108,109

The burden of side effects is shaped by several factors, such as medication type and dose, polypharmacy, individual susceptibility, and comorbid health conditions.110 Adverse effects can directly impair physical health, limit participation in work or social activities, and exacerbate stigma, particularly when visible symptoms (eg, tremor, weight changes) occur.103,104 Some side effects, such as metabolic complications, also contribute to elevated cardiovascular and all-cause mortality in this population.103

Systemic Barriers

Systemic barriers operate at the level of health care structures and social policy, shaping the environment in which recovery occurs. Limited access to appropriate care, lack of vocational rehabilitation resources, and disincentives linked to disability payments can constrain opportunities for functional improvement. These challenges often interact with other drivers resulting in reduced treatment engagement, limiting community participation, and reinforcing functional disability.93

Access to care: Inadequate access to quality mental healthcare, particularly early intervention programs, can impede recovery and worsen disability.93

Vocational support: a lack of effective vocational training and employment support programs limits opportunities for people with schizophrenia to find and maintain competitive employment.111

Disability benefits: while disability benefits provide crucial support, the structure of some benefit systems may create disincentives to seeking employment due to the link between benefits and health insurance.112

Consensus Statement #3

“A range of psychosocial interventions, including cognitive behavioral therapy, cognitive remediation, social skills training, supported employment, and family-focused therapy, are effective in improving functional outcomes across multiple domains. However, their deployment remains inconsistent and often inadequate.”

Evidence-Based Psychosocial Interventions

While pharmacotherapy remains central to managing schizophrenia, it is insufficient on its own to achieve full functional recovery. Evidence-based psychosocial interventions provide complementary strategies that directly target the cognitive, behavioral, emotional, and social processes underlying disability in schizophrenia. These interventions employ structured, manualized approaches designed to reduce symptom burden, enhance adaptive skills, improve social and occupational functioning, and promote overall recovery.

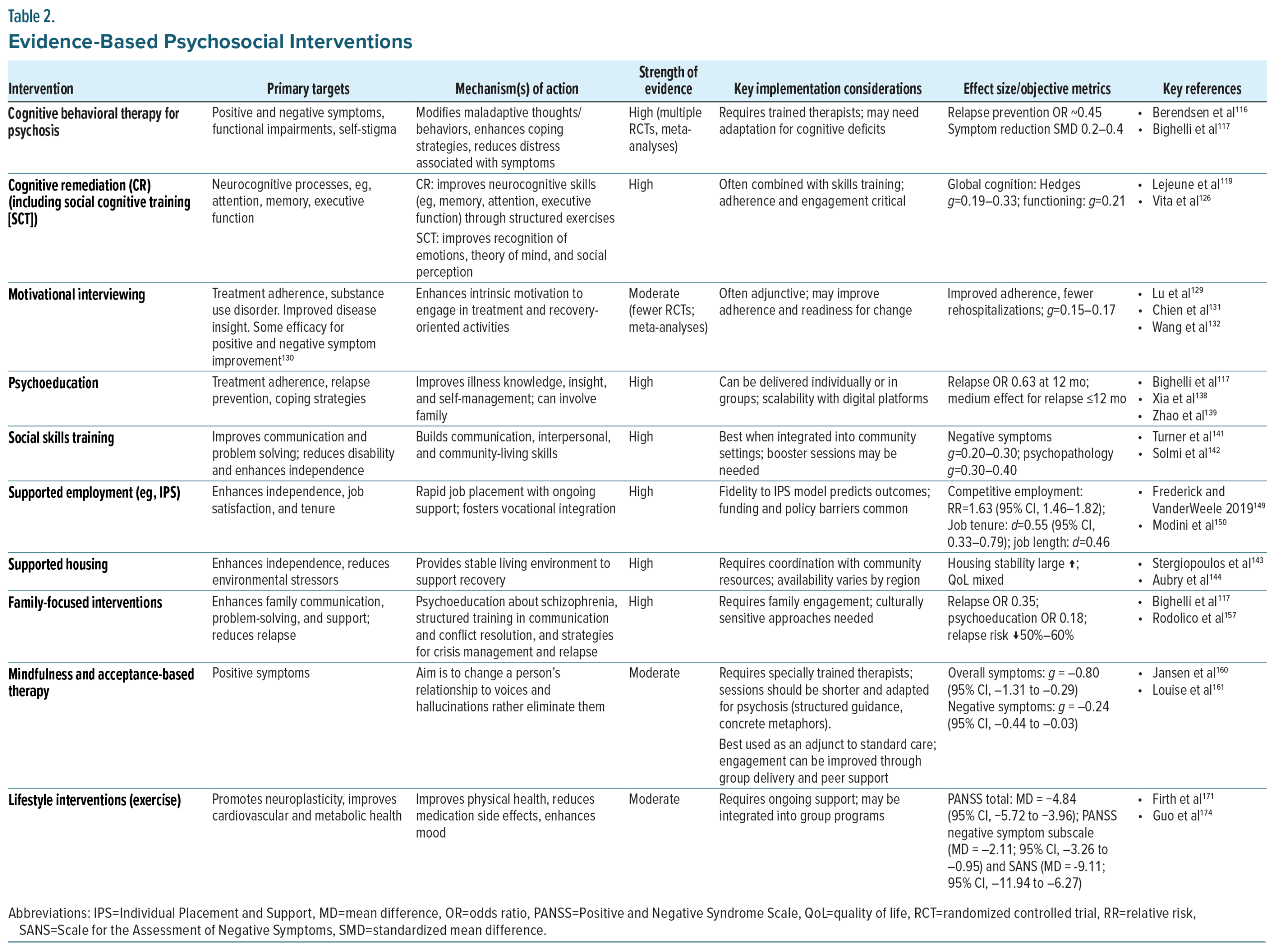

In the section that follows, we review the evidence for key psychosocial and psychotherapeutic interventions. Each subsection highlights the mechanisms of action and strength of evidence for the intervention reviewed as well as key references for additional reading. Because the clinical considerations for implementation are largely consistent across approaches, they are presented collectively in a separate section that follows, rather than repeated within each intervention.

Cognitive Behavioral Therapy

Therapeutic target. Cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT) is a structured, time-limited, and goal-directed intervention that seeks to reduce distress and disability by identifying and modifying maladaptive beliefs and behaviors. In schizophrenia, CBT for psychosis (CBTp) targets positive symptoms, such as hallucinations and delusions, negative symptoms, and functional impairments, by fostering adaptive coping strategies, reality testing, and problem-solving skills. CBT also works to enhance self-efficacy, reduce self-stigma, and improve engagement with treatment and daily activities.18

Evidence. CBT is among the most extensively studied psychosocial interventions for schizophrenia. The American Psychiatric Association (APA) Schizophrenia Guideline (2020), the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) guideline (UK), and the European Psychiatric Association (EPA) all recommend CBT as part of a comprehensive treatment plan, particularly for individuals with persistent positive symptoms despite antipsychotic therapy.13,113,114 Meta-analyses and large randomized controlled trials demonstrate that CBT produces modest but significant improvements in psychotic symptoms, depression, and functioning, particularly in people with schizophrenia with persistent symptoms despite antipsychotic treatment.115 An umbrella review of meta-analyses confirms small-to-medium effects on general and positive symptoms at end of treatment (Table 2).116 Additionally, CBTp has demonstrated evidence for relapse prevention as part of a broader treatment plan.117 Effects on functioning are generally smaller than for symptom reduction; however, the consistency of findings across trials supports CBT as a valuable adjunctive intervention.118

Cognitive Remediation (Including Social Cognitive Training)

Therapeutic target. Cognitive remediation (CR) is a structured, behavioral intervention designed to improve neurocognitive processes, such as attention, memory, and executive function, with downstream benefits for daily functioning.119 Training typically involves repeated, targeted practice of cognitive tasks that are adapted in their difficulty level, often supported by strategy coaching and real-world application. Social cognitive training is a related approach that targets social cognitive domains, such as emotion recognition, theory of mind, and attributional style, abilities that are strongly linked to social functioning in schizophrenia.119,120

Evidence. CR is one of the most extensively studied psychosocial interventions in schizophrenia, with more than 50 randomized controlled trials. The EPA explicitly recommends CR,114 particularly when combined with psychosocial rehabilitation, to improve functional outcomes. The APA Schizophrenia Guideline also acknowledges CR as a beneficial adjunctive intervention.121

A large body of randomized controlled trials and meta-analyses demonstrates that CR produces moderate improvements in global cognition, with downstream effects on psychosocial functioning and community outcomes.119,122,123 Gains are most robust when CR is combined with rehabilitation supports, such as vocational training or psychosocial rehabilitation.124 Social cognitive training also shows significant benefits, particularly in emotion recognition and theory of mind, which sometimes translate into improved social competence and interpersonal outcomes.120 More recent meta-analyses indicate that these improvements may extend beyond test performance to real-world functional domains, including employment, social relationships, and independent living.125

The most comprehensive and methodologically rigorous meta-analysis to date synthesized 130 randomized controlled trials including 8851 participants and confirmed small-to-moderate effects on both global cognition (d = 0.29) and functioning (d = 0.22). Importantly, the presence of an active therapist, structured development of cognitive strategies, and integration with psychosocial rehabilitation significantly enhanced outcomes. Patients with lower education, lower premorbid IQ, and greater baseline symptom severity derived particular benefit, underscoring the broad applicability of CR across illness stages.126

Optimal delivery involves repeated, structured practice (eg, 2–3 sessions per week for several months) with therapist support to promote generalization of skills into daily life.127 Combining CR with supported employment, social skills training, or other rehabilitation programs maximizes transfer to functional outcomes.124 For greatest impact, CR should be embedded within comprehensive treatment plans, tailored to individual cognitive profiles, and explicitly linked to functional rehabilitation goals.127

Motivational Interviewing

Therapeutic target. Motivational interviewing (MI) is a collaborative, person-centered counseling style that helps individuals resolve ambivalence about change and enhance intrinsic motivation. In schizophrenia, MI is most often applied to improve treatment adherence and address co-occurring substance use disorders. By emphasizing empathy, reflective listening, and empowerment, MI facilitates engagement, builds therapeutic alliance, and promotes goal-directed behavior change.128

Evidence. Systematic reviews and meta-analyses indicate that MI is effective in improving medication adherence and reducing substance abuse among individuals with schizophrenia and other serious mental illnesses. In medication adherence studies, MI has been associated with improved insight, stronger alliance with providers, and increased continuation of treatment.129–132 When combined with psychoeducation or cognitive-behavioral strategies, MI demonstrates additional benefits for improving negative symptoms.133 While effect sizes are modest, MI has shown consistent utility as an engagement- and adherence-enhancing intervention.130 To date, no major psychiatric or neurological professional society has formally endorsed MI specifically for improving functional outcomes, although MI is commonly referenced in behavioral health and implementation toolkits as an evidence-based method to support engagement, adherence, and readiness to change.

Psychoeducation

Therapeutic target. Psychoeducation seeks to improve illness understanding and self-management skills for people with schizophrenia and their families. By providing structured information on the nature of schizophrenia, treatment options, early warning signs of relapse, and coping strategies, psychoeducation empowers patients and caregivers to take an active role in care. This increases adherence, reduces stress and expressed emotion in families, and builds the foundation for more effective engagement in rehabilitation.134

Evidence. Psychoeducation is one of the most consistently supported psychosocial interventions in schizophrenia. The APA, the EPA, and the World Federation of Societies of Biological Psychiatry all recommend structured psychoeducation for patients and families as part of standard treatment.114,121,135 The NICE schizophrenia guideline (UK) similarly endorses family intervention incorporating psychoeducation.136

Beyond guideline endorsements, multiple meta-analyses show that psychoeducation reliably reduces relapse and rehospitalization rates with moderate effect while improving medication adherence and functional outcomes, including social and occupational functioning.137–139 These benefits are robust across delivery formats (individual, group, or family-based) and across cultural contexts, with medium effect sizes (Table 2).

Social Skills Training

Therapeutic target. Social skills training (SST) uses behavioral techniques such as modeling, role-play, feedback, and reinforcement to teach concrete interpersonal and daily living skills. The goal is to improve communication, assertiveness, problem-solving, and community functioning, thereby reducing disability and enhancing independence.140

Evidence. The APA and EPA both endorse SST as an evidence-based psychosocial intervention for schizophrenia, particularly for improving functional outcomes.114,121 Meta-analyses and systematic reviews consistently demonstrate that SST enhances social functioning, independent living skills, and vocational outcomes, with effect sizes in the small-to-moderate range.141,142 Evidence also supports combining SST with cognitive remediation or supported employment to maximize generalization to real-world outcomes.

Supported Employment, Education, and Housing

Therapeutic target. Supported housing provides individuals with schizophrenia access to safe, permanent housing with flexible support services. The Housing First model emphasizes immediate access to independent housing without preconditions, such as sobriety or treatment adherence, coupled with mobile clinical support. Stable housing reduces environmental stressors and enables consistent engagement in care, social relationships, and rehabilitation.143,144

Supported employment, most commonly delivered through the Individual Placement and Support (IPS) model, helps individuals with schizophrenia obtain and sustain competitive jobs in the open labor market and is endorsed by both the APA and EPA.114,121 IPS emphasizes rapid job search, matching work to individual preferences, integration with mental health care, and ongoing support without time limits. Employment itself is viewed as a therapeutic tool, fostering self-efficacy, social inclusion, and independence. Emerging evidence demonstrates that supported education, often delivered in parallel with or integrated into IPS, can meaningfully enhance functional recovery for individuals with schizophrenia, particularly younger adults pursuing vocational–academic pathways.145

Evidence. The NICE 2020 rehabilitation guideline146 recommends supported accommodation and housing interventions as key components of long-term recovery for complex psychosis. Large, randomized trials and systematic reviews consistently show that supported housing substantially improves housing stability compared with treatment as usual.144,147 While direct effects on symptoms are modest, functional and quality-of-life outcomes improve when stable housing is paired with clinical and psychosocial support.

Supported employment is one of the most consistently validated psychosocial interventions in schizophrenia. In addition to APA and EPA endorsement, multiple meta-analyses and large randomized controlled trials show that IPS more than doubles the likelihood of competitive employment compared with traditional vocational rehabilitation, with additional benefits in work tenure, income, and quality of life.148–150 Importantly, IPS has demonstrated effectiveness across stages of illness, including early psychosis, and across diverse cultural and health system contexts, underscoring its generalizability.

Supported education is likewise supported by systematic reviews which have demonstrated that supported education improves postsecondary enrollment, persistence, and academic achievement, with effect sizes comparable to early IPS interventions.145 Moreover, guidelines now recognize supported education as an important component of recovery-oriented care, particularly within coordinated specialty care models for early psychosis.13,114,146

Family-Focused Interventions

Therapeutic target. Family-focused interventions target the interpersonal environment, aiming to reduce relapse risk and support recovery by modifying patterns of communication, expressed emotion, and problem-solving within the family unit.151,152 Core components typically include psychoeducation about schizophrenia, structured training in communication and conflict resolution, and strategies for crisis management and relapse prevention.153,154 By equipping families with skills to manage stress and foster collaborative approaches to care, these interventions create a supportive context that promotes treatment adherence, functional gains, and long-term recovery.154–156

Evidence. A robust body of randomized controlled trials and meta-analyses demonstrates that family-focused interventions significantly reduce relapse and rehospitalization rates compared with standard treatment.117,155,157 A network meta-analysis of 90 trials (n >10,000) found that nearly all family intervention models significantly reduced relapse at 12 months, with family psychoeducation showing the strongest effect (Table 2). Other reviews estimate that family interventions can reduce relapse risk by 50%–60%.157 Benefits extend beyond symptom reduction, with improvements in medication adherence, functional outcomes, and quality of life and reductions in caregiver burden.117,155–157 Evidence suggests that structured, multi-session formats are most effective, particularly when initiated early in the illness course.155,158 Culturally adapted models have also demonstrated effectiveness in improving engagement and outcomes across diverse populations.156,159 Major guidelines and professional societies endorse family-focused interventions and psychoeducation.14,121,136

Mindfulness and Acceptance-Based Therapies

Mechanism of action. Mindfulness-based interventions (MBIs) and acceptance-based approaches (eg, acceptance and commitment therapy [ACT]) aim to change a person’s relationship to voices and intrusive thoughts rather than eliminate them. Core processes include present-focused attention, acceptance to reduce experiential avoidance, cognitive defusion/decentering from distressing internal events, and values-guided actions to enhance psychological flexibility. These mechanisms are linked to reductions in distress and improved functioning in psychosis.160-162 In a mediation analysis using inpatient ACT data, reduced believability of hallucinations (defusion) explained decreases in hallucination-related distress, supporting a mechanism of “changing the relation to symptoms.”163

Evidence. Meta-analyses and systematic reviews in schizophrenia-spectrum samples show small-to-moderate improvements in total and positive symptoms, mood, negative symptoms, and functioning and (in some analyses) reduced hospitalization when mindfulness/acceptance approaches are added to usual care.160-162,164 ACT-focused meta-analysis suggests small effects and emphasizes heterogeneity and risk-of-bias considerations, tempering earlier pooled estimates.165 Representative randomized trials include brief ACT adjuncts for inpatients showing lower rehospitalization at 4 months and short-term gains in affect and hallucination-related distress,166,167 group Person-Based Cognitive Therapy/mindfulness for distressing voices reducing voice-related distress,168 and an MBI-psychoeducation program improving symptoms, functioning, insight, and rehospitalization outcomes versus psychoeducation or treatment as usual at 6 months.169

Lifestyle Interventions (Physical Activity)

Therapeutic target. Physical exercise promotes neuroplasticity, improves cardiovascular and metabolic health, and reduces inflammation and oxidative stress, factors implicated in the pathophysiology of schizophrenia. Exercise also enhances the release of neurotrophic factors, such as brain-derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF), which supports synaptic plasticity and cognitive function.170,171 Structural brain benefits, such as increased hippocampal volume and white matter integrity, have also been observed.172 Beyond biological effects, exercise provides behavioral activation, structured daily activity, and opportunities for social engagement, all of which contribute to improved functioning.171,173

Evidence. Meta-analyses demonstrate that aerobic and resistance exercise significantly improve cardiorespiratory fitness, negative symptoms, depressive symptoms, cognition, and overall functioning in individuals with schizophrenia.171,173 One recent meta-analysis found that adjunctive aerobic exercise significantly reduces Positive and Negative Syndrome Scale (PANSS) total scores (MD = −4.84, 95% CI, −5.72 to −3.96), with notable reductions in negative symptoms when conducted for 2–3 months at 100–220 minutes per week.174 Another review comparing modalities found that aerobic exercise significantly decreased PANSS negative symptom scores, whereas resistance training alone had less impact, and combined training showed mixed results.175 Additionally, exercise interventions (particularly aerobic) yield small but meaningful improvements in working memory in schizophrenia spectrum disorders.176 In clinical trials, combining aerobic exercise with computerized cognitive remediation therapy produced stronger improvements in processing speed, cognitive flexibility, negative symptoms, and serum BDNF compared to exercise alone.177 Exercise alone also increases BDNF levels and shows preliminary cognitive gains, though cognitive benefits may lag behind neurotrophic changes.178,179

Consensus Statement #4

“Despite robust evidence of moderate benefit, real-world utilization of psychosocial interventions is limited by access, workforce shortages, inadequate training, and low provider expectations. Addressing these barriers is essential to translating evidence into outcomes. Additionally, each of these psychosocial interventions needs refinements to facilitate individualized application.”

Implementation Strategies, Future Directions, and Conclusions

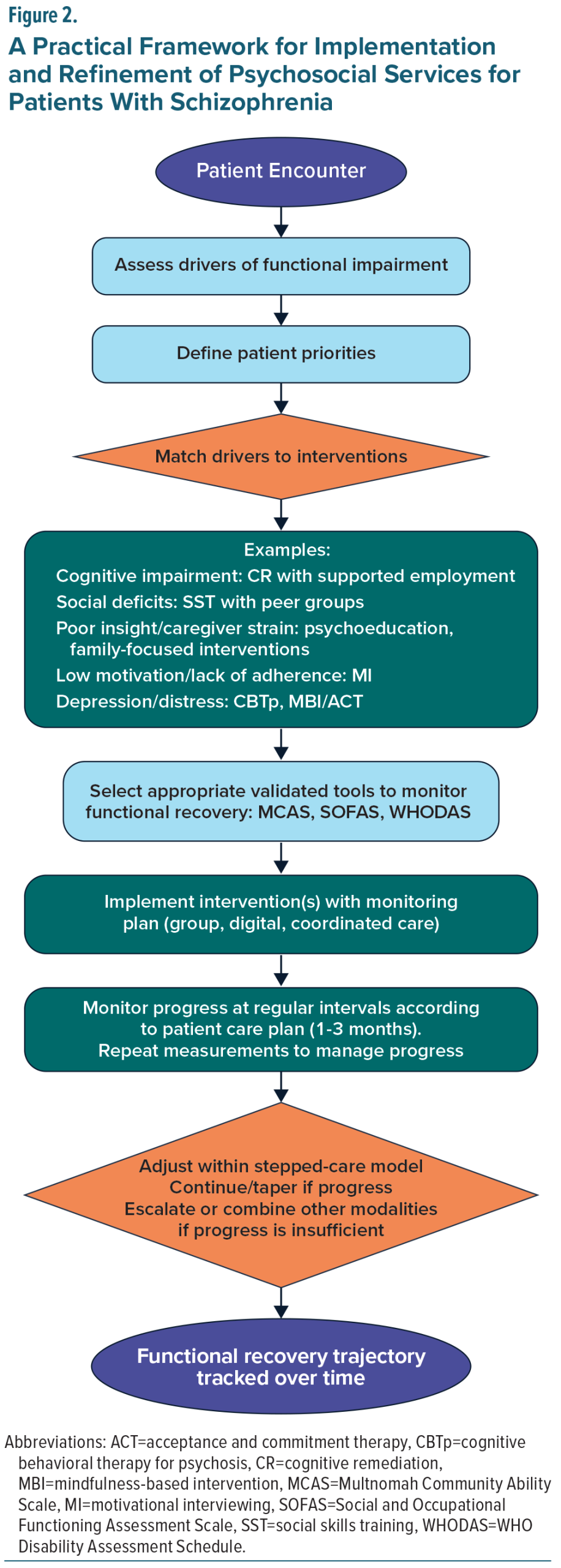

A practical framework for implementing psychosocial interventions in schizophrenia begins with a structured assessment of the key drivers of functional impairment for the individual patient. These may include negative symptoms, cognitive deficits, diminished insight, depressive symptoms, social disconnection, substance use, or social determinants of health.180,181 Organizing these domains, as outlined in Table 1, helps clinicians identify priority targets for intervention and clarify the mechanisms most likely to support improvement.

Interventions should then be selected and matched to the specific driver(s) identified, guided by the mechanisms of action summarized in Table 2. Additionally, efficiencies can often be achieved by combining complementary interventions, as certain approaches are particularly effective when delivered together. For example, cognitive remediation is most appropriate for patients with prominent cognitive deficits and is particularly effective when paired with supported employment, a combination shown to enhance generalization of cognitive gains and produce meaningful improvements in vocational functioning.182,183 Similarly, social skills training may be complemented by social cognition interventions to strengthen both the perceptual and behavioral components of social interaction.120,184 Psychoeducation may be reinforced through family-focused interventions, which extend skill-building to the caregiving environment and improve communication, engagement, and relapse prevention.137,185 Motivational interviewing can be integrated with adherence-focused interventions to improve engagement and reduce disengagement risk in schizophrenia186 and can also be used adjunctively with cognitive-behavioral therapies to strengthen motivation and treatment commitment.187 Even lifestyle interventions, including structured exercise, may be layered onto other psychosocial approaches to improve energy, reduce depressive symptoms, and support overall functional capacity.171 Incorporating these evidence-based combinations enhances efficiency, allows interventions to reinforce one another, and better addresses the multifaceted challenges that contribute to functional impairment.

Successful implementation also requires grounding treatment in each patient’s priorities, such as returning to work or school, maintaining independent living, or improving social connection.188 Shared decision-making ensures that selected interventions are feasible, personally meaningful, and more likely to be sustained. Anchoring interventions in patient-defined functional goals also creates a natural structure for measurement, review, and iterative refinement (Figure 2).

Routine, measurement-based assessment is central to this framework. Validated functional outcome measures, including the Multnomah Community Ability Scale, Social and Occupational Functioning Assessment Scale, Personal and Social Performance scale, and WHO Disability Assessment Schedule (WHODAS) 2.0, offer reliable ways to track change over time.189–192 Embedding these measures into electronic medical records or collecting them via patient-reported digital platforms facilitates integration into routine workflows, supports collaborative review, and strengthens communication across the treatment team. Regular reassessment allows clinicians to determine whether interventions, alone or in combination, are producing the intended functional gains and to identify early signs of stagnation, skill plateau, or new barriers.

The framework is designed to support a flexible, iterative approach within a stepped-care model. Patients may begin with lower-intensity or more scalable interventions (eg, group psychoeducation, brief CBTp), with escalation to more intensive or multimodal strategies if progress is limited.124,181 Measurement-based feedback guides the timing and selection of these adjustments, ensuring that treatment plans remain dynamic and responsive to the evolving needs, goals, and stage of illness of each patient. When progress is slow, combining interventions, rather than simply increasing intensity, may offer the greatest advantage by targeting complementary mechanisms and addressing multiple drivers simultaneously.

Pharmacotherapy remains essential in comprehensive care, yet no medications are approved for negative symptoms or cognitive impairment. At the same time, emerging digital therapeutics offer scalable, evidence-based strategies to augment psychosocial care. The recent CONVOKE trial (NCT05838625) in which the digital therapeutic CT-155 significantly improved experiential negative symptoms as measured by the Motivation and Pleasure subscale of the Clinical Assessment Interview for Negative Symptoms exemplifies the potential of these innovations.193 Importantly, such technologies should be understood as tools that extend reach and sustainability rather than as replacements for psychosocial care.

The consensus panel concludes that effective psychosocial interventions are well established but remain underutilized, not because of uncertain efficacy but due to systemic, financial, and cultural barriers. Randomized controlled trials and meta-analyses consistently show improvements in symptoms, cognition, functional capacity, and quality of life across multiple modalities, yet translation into practice is limited. A practical framework for progress begins with systematic assessment of the drivers of functional impairment and aligning interventions accordingly, supported by validated outcome measures and iterative, patient-centered treatment adjustments (Table 2, Figure 2).

Taken together, the evidence supports a clear mandate: to close the gap between research and practice, care must be grounded in patient priorities, informed by validated measurement, and delivered through recovery-oriented, multimodal, and digitally enabled strategies. By doing so, clinicians can help shift the field from a narrow focus on symptom control toward a paradigm of meaningful functional recovery.

FINANCIAL DISCLOSURES

All authors received an honorarium from Boehringer-Ingelheim Pharmaceuticals, Inc., for participation in the panel meeting.

Dr Tandon has received an unrestricted educational grant from Boehringer-Ingelheim. Dr Buchanan has received advisory board fees from Acadia, Karuna, Merck, and Neurocrine. Dr Keshavan has received consulting fees from Alkermes and Bristol-Myers Squibb. Dr Marder has received consulting fees from Boehringer-Ingelheim, Otsuka, Merck, Sunovion, Karuna, Neurocrine, and Newron and grant/research support from Boehringer-Ingelheim. Dr Nasrallah has received consulting fees from Boehringer-Ingelheim, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Janssen, Karuna, and Cerevel; honoraria for speaking/teaching from Abbvie, Alkermes, Acadia, Axsome, Intra-Cellular, Janssen, Neurocrine, Otsuka, Vanda, and Teva; and advisory board fees from Boehringer-Ingelheim. Drs Barch, Green, and Vita report no other relevant financial relationships.

References (193)

- GBD 2021 Diseases and Injuries Collaborators. Global incidence, prevalence, years lived with disability (YLDs), disability-adjusted life-years (DALYs), and healthy life expectancy (HALE) for 371 diseases and injuries in 204 countries and territories and 811 subnational locations, 1990–2021: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2021. Lancet. May 18 2024;403(10440):2133–2161. doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(24)00757-8

- Solmi M, Seitidis G, Mavridis D, et al. Incidence, prevalence, and global burden of schizophrenia—data, with critical appraisal, from the Global Burden of Disease (GBD) 2019. Mol Psychiatry. Dec 2023;28(12):5319–5327. doi.org/10.1038/s41380-023-02138-4

- Lin C, Zhang X, Jin H. The societal cost of schizophrenia: an updated systematic review of cost-of-illness studies. Pharmacoeconomics. Feb 2023;41(2):139–153. doi.org/10.1007/s40273-022-01217-8

- Tandon R, Gaebel W, Barch DM, et al. Definition and description of schizophrenia in the DSM-5. Schizophr Res. Oct 2013;150(1):3–10. doi.org/10.1016/j.schres.2013.05.028

- American Psychiatric Association. Schizophrenia spectrum and other psychotic disorders. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, 5th Edition, Text Revision (DSM-5-TR). American Psychiatric Publishing; 2022.

- Millan MJ, Agid Y, Brune M, et al. Cognitive dysfunction in psychiatric disorders: characteristics, causes and the quest for improved therapy. Nat Rev Drug Discov. Feb 1 2012;11(2):141–68. doi.org/10.1038/nrd3628

- Barch DM, Bustillo J, Gaebel W, et al. Logic and justification for dimensional assessment of symptoms and related clinical phenomena in psychosis: relevance to DSM-5. Schizophr Res. Oct 2013;150(1):15–20. doi.org/10.1016/j.schres.2013.04.027

- Govil P, Kantrowitz JT. Negative symptoms in schizophrenia: an update on research assessment and the current and upcoming treatment landscape. CNS Drugs. Mar 2025;39(3):243–262. doi.org/10.1007/s40263-024-01151-7

- Tandon R, Nasrallah H, Akbarian S, et al. The schizophrenia syndrome, circa 2024: what we know and how that informs its nature. Schizophr Res. Feb 2024;264:1–28. doi.org/10.1016/j.schres.2023.11.015

- Nasrallah H, Tandon R, Keshavan M. Beyond the facts in schizophrenia: closing the gaps in diagnosis, pathophysiology, and treatment. Epidemiol Psychiatr Sci. Dec 2011;20(4):317–27. doi.org/10.1017/s204579601100062x

- Silva MA, Restrepo D. Functional recovery in schizophrenia. Rev Colomb Psiquiatr (Engl Ed). Oct-Dec 2019;48(4):252–260. Recuperacion funcional en la esquizofrenia. doi.org/10.1016/j.rcp.2017.08.004

- Tandon R, Targum SD, Nasrallah HA, et al. Strategies for maximizing clinical effectiveness in the treatment of schizophrenia. J Psychiatr Pract. Nov 2006;12(6):348–63. doi.org/10.1097/00131746-200611000-00003

- Keepers GA, Fochtmann LJ, Anzia JM, et al. The American Psychiatric Association Practice Guideline for the Treatment of Patients With Schizophrenia. Am J Psychiatry. Sep 1 2020;177(9):868–872. doi.org/10.1176/appi.ajp.2020.177901

- Zhou W, Han H, Xiao X, et al. Assessing functional disability in schizophrenia patients receiving the Management and Treatment Services for Psychosis in China: implications for community mental health services. Asian J Psychiatr. Jan 2025;103:104319. doi.org/10.1016/j.ajp.2024.104319

- Harris A, Boyce P. Why do we not use psychosocial interventions in the treatment of schizophrenia? Aust N Z J Psychiatry. Jun 2013;47(6):501–4. doi.org/10.1177/0004867413489173

- Vita A, Barlati S. The implementation of evidence-based psychiatric rehabilitation: challenges and opportunities for mental health services. Front Psychiatry. 2019;10:147. doi.org/10.3389/fpsyt.2019.00147

- Gupta N, Gupta M, Esang M. Lost in translation: challenges in the diagnosis and treatment of early-onset schizophrenia. Cureus. May 2023;15(5):e39488. doi.org/10.7759/cureus.39488

- Barlati S, Nibbio G, Vita A. Evidence-based psychosocial interventions in schizophrenia: a critical review. Curr Opin Psychiatry. May 1 2024;37(3):131–139. doi.org/10.1097/YCO.0000000000000925

- Vita A, Barlati S. Recovery from schizophrenia: is it possible? Curr Opin Psychiatry. May 2018;31(3):246–255. doi.org/10.1097/YCO.0000000000000407

- Tandon R, Devellis RF, Han J, et al. Validation of the Investigator’s Assessment Questionnaire, a new clinical tool for relative assessment of response to antipsychotics in patients with schizophrenia and schizoaffective disorder. Psychiatry Res. Sep 15 2005;136(2–3):211–21. doi.org/10.1016/j.psychres.2005.05.006

- Yu B, Sun Z, Li S, et al. Social isolation and cognitive function in patients with schizophrenia: a two years follow-up study. Schizophr Res. May 2024;267:150–155. doi.org/10.1016/j.schres.2024.03.035

- Thomas EC, Snethen G, Salzer MS. Community participation factors and poor neurocognitive functioning among persons with schizophrenia. Am J Orthopsychiatry. 2020;90(1):90–97. doi.org/10.1037/ort0000399

- Marwaha S, Johnson S. Schizophrenia and employment—a review. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol. May 2004;39(5):337–49. doi.org/10.1007/s00127-004-0762-4

- Calzavara-Pinton I, Nibbio G, Barlati S, et al. Treatment of cognitive impairment associated with schizophrenia spectrum disorders: new evidence, challenges, and future perspectives. Brain Sci. Aug 6 2024;14(8):791.doi.org/10.3390/brainsci14080791

- Ruiz-Castaneda P, Santiago Molina E, Aguirre Loaiza H, et al. Positive symptoms of schizophrenia and their relationship with cognitive and emotional executive functions. Cogn Res Princ Implic. Aug 12 2022;7(1):78. doi.org/10.1186/s41235-022-00428-z

- Tandon R, DeQuardo JR, Taylor SF, et al. Phasic and enduring negative symptoms in schizophrenia: biological markers and relationship to outcome. Schizophr Res. Oct 27 2000;45(3):191–201. doi.org/10.1016/s0920-9964(99)00163-2

- Kirkpatrick B, Fenton WS, Carpenter WT, Jr., et al. The NIMH-MATRICS consensus statement on negative symptoms. Schizophr Bull. Apr 2006;32(2):214–9. doi.org/10.1093/schbul/sbj053

- Blanchard JJ, Cohen AS. The structure of negative symptoms within schizophrenia: implications for assessment. Schizophr Bull. Apr 2006;32(2):238–45. doi.org/10.1093/schbul/sbj013

- Howes OD, Fusar-Poli P, Bloomfield M, et al. From the prodrome to chronic schizophrenia: the neurobiology underlying psychotic symptoms and cognitive impairments. Curr Pharm Des. 2012;18(4):459–65. doi.org/10.2174/138161212799316217

- Green MF, Horan WP, Lee J. Nonsocial and social cognition in schizophrenia: current evidence and future directions. World Psychiatry. Jun 2019;18(2):146–161. doi.org/10.1002/wps.20624

- Allott K, Liu P, Proffitt TM, et al. Cognition at illness onset as a predictor of later functional outcome in early psychosis: systematic review and methodological critique. Schizophr Res. Feb 2011;125(2–3):221–35. doi.org/10.1016/j.schres.2010.11.001

- Giuliano AJ, Li H, Mesholam-Gately RI, et al. Neurocognition in the psychosis risk syndrome: a quantitative and qualitative review. Curr Pharm Des. 2012;18(4):399–415. doi.org/10.2174/138161212799316019

- Szoke A, Trandafir A, Dupont ME, et al. Longitudinal studies of cognition in schizophrenia: meta-analysis. Br J Psychiatry. Apr 2008;192(4):248–57. doi.org/10.1192/bjp.bp.106.029009

- McCutcheon RA, Keefe RSE, McGuire PK. Cognitive impairment in schizophrenia: aetiology, pathophysiology, and treatment. Mol Psychiatry. May 2023;28(5):1902–1918. doi.org/10.1038/s41380-023-01949-9

- Bowie CR, Harvey PD. Cognition in schizophrenia: impairments, determinants, and functional importance. Psychiatr Clin North Am. Sep 2005;28(3):613–33, 626. doi.org/10.1016/j.psc.2005.05.004

- Gebreegziabhere Y, Habatmu K, Mihretu A, et al. Cognitive impairment in people with schizophrenia: an umbrella review. Eur Arch Psychiatry Clin Neurosci. Oct 2022;272(7):1139–1155. doi.org/10.1007/s00406-022-01416-6

- Elvevag B, Goldberg TE. Cognitive impairment in schizophrenia is the core of the disorder. Crit Rev Neurobiol. 2000;14(1):21. doi.org/10.1615/CritRevNeurobiol.v14.i1.10

- Henriksen MG, Parnas J. Self-disorders and schizophrenia: a phenomenological reappraisal of poor insight and noncompliance. Schizophr Bull. May 2014;40(3):542–7. doi.org/10.1093/schbul/sbt087

- Roux P, Faivre N, Urbach M, et al. Relationships between neuropsychological performance, insight, medication adherence, and social metacognition in schizophrenia. Schizophr Res. Feb 2023;252:48–55. doi.org/10.1016/j.schres.2022.12.037

- Sakai Y, Ito S, Matsumoto J, et al. Longitudinal characteristics of insight and clinical factors in patients with schizophrenia. Neuropsychopharmacol Rep. Sep 2023;43(3):373–381. doi.org/10.1002/npr2.12356

- Keshavan MS, Rabinowitz J, DeSmedt G, et al. Correlates of insight in first episode psychosis. Schizophr Res. Oct 1 2004;70(2–3):187–94. doi.org/10.1016/j.schres.2003.11.007

- Osatuke K, Ciesla J, Kasckow JW, et al. Insight in schizophrenia: a review of etiological models and supporting research. Compr Psychiatry. Jan-Feb 2008;49(1):70–7. doi.org/10.1016/j.comppsych.2007.08.001

- Velligan DI, Sajatovic M, Hatch A, et al. Why do psychiatric patients stop antipsychotic medication? a systematic review of reasons for nonadherence to medication in patients with serious mental illness. Patient Prefer Adherence. 2017;11:449–468. doi.org/10.2147/ppa.S124658

- Ramu N, Kolliakou A, Sanyal J, et al. Recorded poor insight as a predictor of service use outcomes: cohort study of patients with first-episode psychosis in a large mental healthcare database. BMJ Open. Jun 12 2019;9(6):e028929. doi.org/10.1136/bmjopen-2019-028929

- Semahegn A, Torpey K, Manu A, et al. Psychotropic medication non-adherence and its associated factors among patients with major psychiatric disorders: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Systematic Reviews. 2020;9(1):17. doi.org/10.1186/s13643-020-1274-3

- Kane JM, Kishimoto T, Correll CU. Non-adherence to medication in patients with psychotic disorders: epidemiology, contributing factors and management strategies. World Psychiatry. Oct 2013;12(3):216–26. doi.org/10.1002/wps.20060

- Emsley R, Chiliza B, Asmal L, et al. The nature of relapse in schizophrenia. BMC Psychiatry. Feb 8 2013;13:50. doi.org/10.1186/1471-244X-13-50

- Harvey PD, Rosenthal JB. Cognitive and functional deficits in people with schizophrenia: evidence for accelerated or exaggerated aging? Schizophr Res. Jun 2018;196:14–21. doi.org/10.1016/j.schres.2017.05.009

- Strassnig MT, Harvey PD. Treatment resistance and other complicating factors in the management of schizophrenia. CNS Spectr. Dec 2014;19 Suppl 1:16–23; quiz 13–5, 24. doi.org/10.1017/S1092852914000571

- Nesvag R, Knudsen GP, Bakken IJ, et al. Substance use disorders in schizophrenia, bipolar disorder, and depressive illness: a registry-based study. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol. Aug 2015;50(8):1267–76. doi.org/10.1007/s00127-015-1025-2

- Archibald L, Brunette MF, Wallin DJ, et al. Alcohol use disorder and schizophrenia or schizoaffective disorder. Alcohol Res. 2019;40(1):arcr.v40.1.06.doi.org/10.35946/arcr.v40.1.06

- Chesney E, Lawn W, McGuire P. Assessing cannabis use in people with psychosis. Cannabis Cannabinoid Res. Feb 2024;9(1):49–58. doi.org/10.1089/can.2023.0032

- Hunt GE, Large MM, Cleary M, et al. Prevalence of comorbid substance use in schizophrenia spectrum disorders in community and clinical settings, 1990-2017: Systematic review and meta-analysis. Drug Alcohol Depend. Oct 1 2018;191:234–258. doi.org/10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2018.07.011

- Lambert M, Conus P, Lubman DI, et al. The impact of substance use disorders on clinical outcome in 643 patients with first-episode psychosis. Acta Psychiatr Scand. Aug 2005;112(2):141–8. doi.org/10.1111/j.1600-0447.2005.00554.x

- Lahteenvuo M, Luykx JJ, Taipale H, et al. Associations between antipsychotic use, substance use and relapse risk in patients with schizophrenia: real-world evidence from two national cohorts. Br J Psychiatry. Dec 2022;221(6):758–765. doi.org/10.1192/bjp.2022.117

- Brunette MF, Mueser KT, Babbin S, et al. Demographic and clinical correlates of substance use disorders in first episode psychosis. Schizophr Res. Apr 2018;194:4–12. doi.org/10.1016/j.schres.2017.06.039

- Hasan A, von Keller R, Friemel CM, et al. Cannabis use and psychosis: a review of reviews. Eur Arch Psychiatry Clin Neurosci. Jun 2020;270(4):403–412. doi.org/10.1007/s00406-019-01068-z

- Khokhar JY, Dwiel LL, Henricks AM, et al. The link between schizophrenia and substance use disorder: a unifying hypothesis. Schizophr Res. Apr 2018;194:78–85. doi.org/10.1016/j.schres.2017.04.016

- Masroor A, Khorochkov A, Prieto J, et al. Unraveling the association between schizophrenia and substance use disorder-predictors, mechanisms and treatment modifications: a systematic review. Cureus. Jul 2021;13(7):e16722. doi.org/10.7759/cureus.16722

- Li Z, Xue M, Zhao L, et al. Comorbid major depression in first-episode drug-naive patients with schizophrenia: analysis of the Depression in Schizophrenia in China (DISC) study. J Affect Disord. Nov 1 2021;294:33–38. doi.org/10.1016/j.jad.2021.06.075

- Krynicki CR, Upthegrove R, Deakin JFW, et al. The relationship between negative symptoms and depression in schizophrenia: a systematic review. Acta Psychiatr Scand. May 2018;137(5):380–390. doi.org/10.1111/acps.12873

- Goldman RS, Tandon R, Liberzon I, et al. Measurement of depression and negative symptoms in schizophrenia. Psychopathology. 1992;25(1):49–56. doi.org/10.1159/000284753

- Siris SG, Addington D, Azorin JM, et al. Depression in schizophrenia: recognition and management in the USA. Schizophr Res. Mar 1 2001;47(2–3):185–97. doi.org/10.1016/s0920-9964(00)00135-3

- van Rooijen G, Vermeulen JM, Ruhe HG, et al. Treating depressive episodes or symptoms in patients with schizophrenia. CNS Spectr. Apr 2019;24(2):239–248. doi.org/10.1017/S1092852917000554

- Campellone TR, Sanchez AH, Kring AM. Defeatist performance beliefs, negative symptoms, and functional outcome in schizophrenia: a meta-analytic review. Schizophr Bull. Nov 2016;42(6):1343–1352. doi.org/10.1093/schbul/sbw026

- Grant PM, Beck AT. Defeatist beliefs as a mediator of cognitive impairment, negative symptoms, and functioning in schizophrenia. Schizophr Bull. Jul 2009;35(4):798–806. doi.org/10.1093/schbul/sbn008

- Lim MH, Manera KE, Owen KB, et al. The prevalence of chronic and episodic loneliness and social isolation from a longitudinal survey. Sci Rep. Aug 1 2023;13(1):12453. doi.org/10.1038/s41598-023-39289-x

- Hajek A, Gyasi RM, Pengpid S, et al. Prevalence of loneliness and social isolation amongst individuals with severe mental disorders: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Epidemiol Psychiatr Sci. Apr 15 2025;34:e25. doi.org/10.1017/S2045796025000228

- Stefanidou T, Wang J, Morant N, et al. Loneliness in early psychosis: a qualitative study exploring the views of mental health practitioners in early intervention services. BMC Psychiatry. Mar 6 2021;21(1):134. doi.org/10.1186/s12888-021-03138-w

- Green MF, Horan WP, Lee J, et al. Social disconnection in schizophrenia and the general community. Schizophr Bull. Feb 15 2018;44(2):242–249. doi.org/10.1093/schbul/sbx082

- Abplanalp SJ, Green MF, Wynn JK, et al. Using machine learning to understand social isolation and loneliness in schizophrenia, bipolar disorder, and the community. Schizophrenia (Heidelb). Oct 5 2024;10(1):88. doi.org/10.1038/s41537-024-00511-y

- Michalska da Rocha B, Rhodes S, Vasilopoulou E, et al. Loneliness in psychosis: a meta-analytical review. Schizophr Bull. Jan 13 2018;44(1):114–125. doi.org/10.1093/schbul/sbx036

- Parcesepe AM, Cabassa LJ. Public stigma of mental illness in the United States: a systematic literature review. Adm Policy Ment Health. Sep 2013;40(5):384–99. doi.org/10.1007/s10488-012-0430-z

- Dubreucq J, Plasse J, Franck N. Self-stigma in serious mental illness: a systematic review of frequency, correlates, and consequences. Schizophr Bull. Aug 21 2021;47(5):1261–1287. doi.org/10.1093/schbul/sbaa181

- Fond G, Vidal M, Joseph M, et al. Self-stigma in schizophrenia: a systematic review and meta-analysis of 37 studies from 25 high- and low-to-middle income countries. Mol Psychiatry. May 2023;28(5):1920–1931. doi.org/10.1038/s41380-023-02003-4

- Barlati S, Morena D, Nibbio G, et al. Internalized stigma among people with schizophrenia: Relationship with socio-demographic, clinical and medication-related features. Schizophr Res. May 2022;243:364–371. doi.org/10.1016/j.schres.2021.06.007

- Assefa D, Shibre T, Asher L, et al. Internalized stigma among patients with schizophrenia in Ethiopia: a cross-sectional facility-based study. BMC Psychiatry. Dec 29 2012;12:239. doi.org/10.1186/1471-244X-12-239

- Bilgin Kocak M, Ozturk Atkaya N. The relationship between internalized stigma with self-reported cognitive dysfunction and insight in schizophrenia. Psychiatry Clin Psychopharmacol. Jun 2024;34(2):119–126. doi.org/10.5152/pcp.2024.23787

- Gagiu C, Dionisie V, Manea MC, et al. Internalised stigma, self-esteem and perceived social support as psychosocial predictors of quality of life in adult patients with schizophrenia. J Clin Med. Nov 19 2024;13(22):6959. doi.org/10.3390/jcm13226959

- Hofer A, Mizuno Y, Frajo-Apor B, et al. Resilience, internalized stigma, self-esteem, and hopelessness among people with schizophrenia: Cultural comparison in Austria and Japan. Schizophr Res. Mar 2016;171(1–3):86–91. doi.org/10.1016/j.schres.2016.01.027

- Lee S, Chiu MY, Tsang A, et al. Stigmatizing experience and structural discrimination associated with the treatment of schizophrenia in Hong Kong. Soc Sci Med. Apr 2006;62(7):1685–96. doi.org/10.1016/j.socscimed.2005.08.016

- Langlois S, Pauselli L, Anderson S, et al. Effects of perceived social status and discrimination on hope and empowerment among individuals with serious mental illnesses. Psychiatry Res. Apr 2020;286:112855. doi.org/10.1016/j.psychres.2020.112855

- Stuart H. Reducing the stigma of mental illness. Glob Ment Health (Camb). 2016;3:e17. doi.org/10.1017/gmh.2016.11

- Hatzenbuehler ML. Structural stigma: Research evidence and implications for psychological science. Am Psychol. Nov 2016;71(8):742–751. doi.org/10.1037/amp0000068

- Schneider M, Muller CP, Knies AK. Low income and schizophrenia risk: a narrative review. Behav Brain Res. Oct 28 2022;435:114047. doi.org/10.1016/j.bbr.2022.114047

- Alegria M, NeMoyer A, Falgas Bague I, et al. Social determinants of mental health: where we are and where we need to go. Curr Psychiatry Rep. Sep 17 2018;20(11):95. doi.org/10.1007/s11920-018-0969-9

- Jeste DJ, Thomas ML, Sturm ET, et al. Review of major social determinants of health in schizophrenia-spectrum psychotic disorders, I: clinical outcomes. Schizophr Bull. Jul 4 2023;49(4):837–850. doi.org/10.1093/schbul/sbad023

- Shim RS, Compton MT. The social determinants of mental health: psychiatrists’ roles in addressing discrimination and food insecurity. Focus (Am Psychiatr Publ). Jan 2020;18(1):25–30. doi.org/10.1176/appi.focus.20190035

- Kirkbride JB, Anglin DM, Colman I, et al. The social determinants of mental health and disorder: evidence, prevention and recommendations. World Psychiatry. Feb 2024;23(1):58–90. doi.org/10.1002/wps.21160

- Fond GB, Yon DK, Tran B, et al. Poverty and inequality in real-world schizophrenia: a national study. Front Public Health. 2023;11:1182441. doi.org/10.3389/fpubh.2023.1182441

- Barry R, Anderson J, Tran L, et al. Prevalence of mental health disorders among individuals experiencing homelessness: a systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA Psychiatry. Jul 1 2024;81(7):691–699. doi.org/10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2024.0426

- Correll CU, Xiang P, Sarikonda K, et al. The economic impact of cognitive impairment and negative symptoms in schizophrenia: a targeted literature review with a focus on outcomes relevant to health care decision-makers in the United States. J Clin Psychiatry. Aug 21 2024;85(3):24r15316. doi.org/10.4088/JCP.24r15316

- Tiller J, Maguire T, Newman-Taylor K. Early intervention in psychosis services: a systematic review and narrative synthesis of barriers and facilitators to seeking access. Eur Psychiatry. Nov 6 2023;66(1):e92. doi.org/10.1192/j.eurpsy.2023.2465

- Hahlweg K, Baucom DH. Family therapy for persons with schizophrenia: neglected yet important. Eur Arch Psychiatry Clin Neurosci. Jun 2023;273(4):819–824. doi.org/10.1007/s00406-022-01393-w

- Claxton M, Onwumere J, Fornells-Ambrojo M. Do family interventions improve outcomes in early psychosis? a systematic review and meta-analysis. Front Psychol. 2017;8:371. doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2017.00371

- Grover S, Sarkar S, Naskar C, et al. Caregiver burden as perceived by caregivers of patients with schizophrenia: a meta-analysis of Indian studies. Asian J Psychiatr. Apr 2025;106:104421. doi.org/10.1016/j.ajp.2025.104421

- Manesh AE, Dalvandi A, Zoladl M. The experience of stigma in family caregivers of people with schizophrenia spectrum disorders: a meta-synthesis study. Heliyon. Mar 2023;9(3):e14333. doi.org/10.1016/j.heliyon.2023.e14333

- Prasad F, Hahn MK, Chintoh AF, et al. Depression in caregivers of patients with schizophrenia: a scoping review. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol. Jan 2024;59(1):1–23. doi.org/10.1007/s00127-023-02504-1

- Chakrabarti S. Cultural aspects of caregiver burden in psychiatric disorders. World J Psychiatry [Internet]. 2013;3(4)

- Citrome L. Activating and sedating adverse effects of second-generation antipsychotics in the treatment of schizophrenia and major depressive disorder: absolute risk increase and number needed to harm. J Clin Psychopharmacol. Apr 2017;37(2):138–147. doi.org/10.1097/JCP.0000000000000665

- Dibonaventura M, Gabriel S, Dupclay L, et al. A patient perspective of the impact of medication side effects on adherence: results of a cross-sectional nationwide survey of patients with schizophrenia. BMC Psychiatry. Mar 20 2012;12:20. doi.org/10.1186/1471-244x-12-20