The term catatonia derives from the Greek words kata (down) and tonas (tension or tone), first described by Dr Karl Kahlbaum in 1874.1,2 Catatonia is recognized as a clinical syndrome characterized by psychomotor symptoms, including catalepsy, waxy flexibility, stupor, posturing, mutism, and agitation.2 Its prevalence among psychiatric patients is significant, ranging from 7% to 38%.3,4 In contrast, delirious mania, also known as “Bell’s mania,” presents with rapid onset of mania, delirium, psychosis, grandiosity, emotional lability, delusions, and insomnia often accompanied by hyperactivity, excitement, and emotional lability, lacking the motor symptoms seen in catatonia. Although electroconvulsive therapy (ECT) is effective in treating Bell’s mania, it remains absent from the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fifth Edition, and International Classification of Diseases, Tenth Revision.5,6

This case highlights the rare and complex presentation of stress- induced, acute-onset catatonia and Bell’s mania in a healthy male adolescent. It underscores the importance of thorough evaluation and diagnostic precision in managing these conditions, particularly in young patients without psychiatric family history.

Case Report

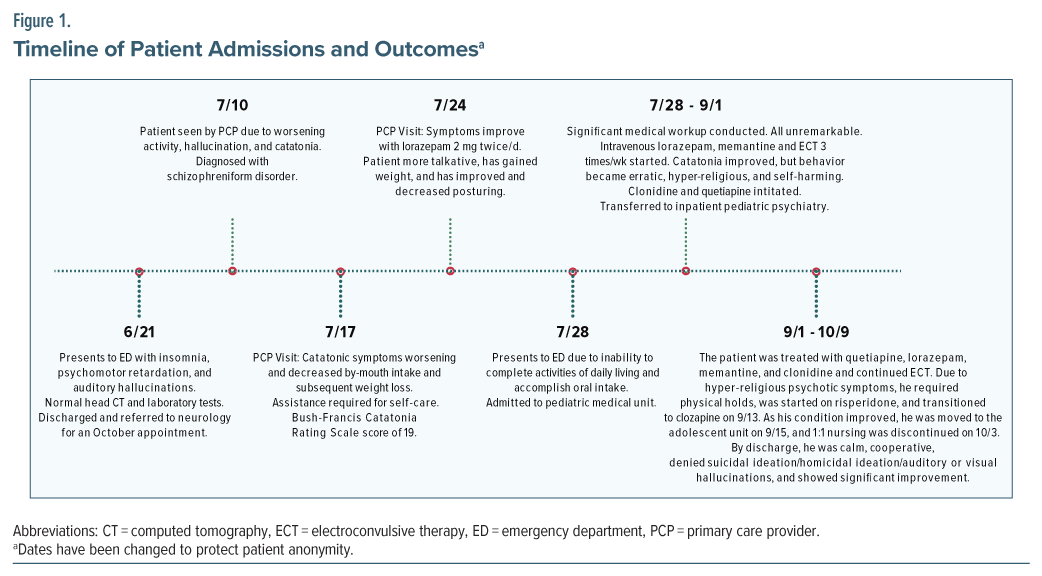

A 17-year-old boy with no significant medical or psychiatric history presented to the emergency department with worsening psychological symptoms, including insomnia and decreased activity after a stressful exam period. Neurological symptoms included head tilting, decreased arm mobility, dragging his right foot, and slowed speech. After unremarkable laboratory tests and scans, including brain magnetic resonance imaging and lumbar puncture, he was discharged with a referral for neurological consultation. Two weeks later, he was diagnosed with schizophreniform disorder by his primary care provider, who also noted slowed responses, flat affect, and stuttering and prescribed lorazepam 2 mg 3 times/day.

Over the next month, he visited his primary care provider 3 times as his symptoms worsened, showing severe catatonia (mute responses, immobility, staring, posturing). He lost 5 lb due to poor oral intake and scored 19 on the Bush-Francis Catatonia Rating Scale (BFCRS).5 His lorazepam dose was increased to 3 mg 3 times/day, but his condition rapidly deteriorated, and he began exhibiting symptoms of Bell’s mania, including acute psychosis, mania, and catatonia, leading to hospitalization.

In the hospital, the patient showed continued catatonia and acute psychosis, including bizarre behavior, hallucinations, paranoia, and hyper- religiosity. Clonidine 0.1 mg twice/day and seroquel 200 mg twice/day and 300 mg at bedtime were initiated, leading to improved mobility and consistent oral intake. He was transferred to an inpatient child/ adolescent psychiatry unit for ongoing treatment.

Treatment included intravenous lorazepam, which was later switched to amantadine, and the initiation of ECT for persistent catatonia and psychosis. Lorazepam was continued for 4 weeks and then transitioned to memantine (10 mg twice daily), which showed greater efficacy for catatonia, though psychosis persisted. Clozapine was introduced and titrated to 200 mg once/day, leading to significant improvement in speech latency, mood stability, and daily activities. The patient was discharged approximately 2 weeks later (Figure 1).

Discussion

This case highlights the complexity of managing severe catatonia in an adolescent with delirious mania, illustrating the diagnostic and therapeutic challenges posed by the overlapping symptoms. The patient required 24 ECT sessions and multiple pharmacologic interventions, with significant improvement only achieved after clozapine was introduced. The combination of delirious mania’s agitation and psychosis with catatonia’s motor abnormalities and unresponsiveness can obscure each condition, complicating diagnosis and treatment. A review of 2 similar cases in adolescents shows a diverse therapeutic approach, with both cases responding to lithium and only 2 sessions of ECT.7,8 These findings underscore gaps in understanding and treatment of severe catatonia associated with delirious mania in adolescents, emphasizing the need for a multidisciplinary approach and further research to optimize management strategies.

Pathogenesis. The pathogenesis of Bell’s mania and catatonia involves overlapping yet distinct neurobiological mechanisms. Bell’s mania is linked to hyperdopaminergic activity and neuroinflammation, with immune dysregulation playing a potential role, similar to autoimmune encephalitis.9 Its treatment response to antipsychotics and ECT supports this theory.10,11 In contrast, catatonia primarily involves dysfunction in GABAergic and glutamatergic signaling within the cortical-striatal- thalamocortical circuits.12,13 Neuroinflammation also contributes, as seen in conditions like anti–N-methyl-D- aspartate (NMDA) receptor encephalitis.13 While both disorders share features such as motor abnormalities and altered mental status, their underlying mechanisms differ.

Diagnostic Methods and Differentials. Bell’s mania is diagnosed by the sudden onset of manic symptoms like excitement, grandiosity, emotional lability, delusions, and insomnia, along with delirium characterized by disorientation and altered consciousness, following the Bond criteria.14 A thorough medical evaluation, including neuroimaging and lumbar puncture with neuronal antibody testing, is essential to rule out underlying causes, especially autoimmune encephalitis.14 Bell’s mania must be differentiated from conditions like catatonia, disorganized psychosis, and neuroleptic malignant syndrome.10 Catatonia is identified by at least 3 of 12 motor signs, such as stupor, waxy flexibility, and mutism, as assessed using the BFCRS.15 Like Bell’s mania, a comprehensive workup including laboratory tests, neuroimaging, and electroencephalogram is needed.15 While catatonia can present with delirium, it is primarily distinguished by motor abnormalities, whereas delirium includes a wider range of cognitive disturbances.14,15

Treatment and Management. While the treatment approaches for Bell’s mania and catatonia differ, there are some overlapping strategies in their management. For Bell’s mania, ECT is the most effective, with most patients responding within 3 to 6 sessions.10,16 High-dose benzodiazepines like lorazepam manage acute symptoms, while atypical antipsychotics and mood stabilizers are used less frequently due to slower onset.16 Typical antipsychotics and anticholinergics should be avoided.16 In catatonia, lorazepam is the first- line treatment, effective in 60%–80% of cases.15 ECT is effective for benzodiazepine-refractory cases, and NMDA receptor antagonists like amantadine are second-line options, while supportive care and cautious use of second-generation antipsychotics may also be necessary.15

Conclusion

This case highlights the need for heightened awareness of Bell’s mania in young adults with rapid-onset psychiatric symptoms, especially after stressors. It emphasizes the importance of individualized treatment plans and early intervention to improve outcomes. The case also underscores the need to consider family history and potential underlying disorders in treatment planning. Further research is essential to understand how stress can trigger severe psychiatric conditions in healthy individuals.

Article Information

Published Online: September 9, 2025. https://doi.org/10.4088/PCC.25cr03953

© 2025 Physicians Postgraduate Press, Inc.

Prim Care Companion CNS Disord 2025;27(5):25cr03953

Submitted: February 27, 2025; accepted May 15, 2025.

To Cite: Forster AA, McDuffee NS, Shah K, et al. Navigating Bell’s mania and catatonia: the role of electroconvulsive therapy in adolescent psychiatry. Prim Care Companion CNS Disord 2025;27(5):25cr03953.

Author Affiliations: Wake Forest School of Medicine, Winston-Salem, North Carolina (Forster, McDuffee); Department of Psychiatry, Atrium Wake Forest Baptist Health, Winston-Salem, North Carolina (Shah, Easterday).

Corresponding Author: Aren A. Forster, BA, Department of Psychiatry, Atrium Wake Forest Baptist Health, Wake Forest School of Medicine, 1 Medical Center Blvd, Winston-Salem, North Carolina 27157 ([email protected]).

Relevant Financial Relationships: None.

Funding/Support: None.

Patient Consent: Consent was received from the patient and his parents to publish the case report, and information, including dates, has been de-identified to protect patient confidentiality.

References (16)

- Bellak L. Dementia Praecox in Childhood. Grune and Stratton; 1947.

- Wilcox JA, Duffy PR. The syndrome of catatonia. Behav Sci (Basel). 2015;5:576–588. PubMed

- Chandra SR, Issac TG, Shivaram S. Catatonia in Children following Systemic Illness. Indian J Psychol Med. 2015;37(4):413–418. PubMed CrossRef

- Taylor MA, Fink M, Fink M. Catatonia in psychiatric classification: a home of its own. Am J Psychiatry. 2003;160(7):1233–1241. PubMed

- Bush G, Fink M, Petrides G, et al. Catatonia. I. Rating scale and standardized examination. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 1996;93(2):129–136. PubMed CrossRef

- American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders. American Psychiatric Publishing; 2013.

- Herken J, Prüss H. Delirious mania as a neuropsychiatric presentation in patients with anti–N- methyl-D-aspartate receptor encephalitis. JAMA Neurol. 2017;74(8):1000–1002. PubMed

- Danivas V, Behere RV, Varambally S, et al. Electroconvulsive therapy in the treatment of delirious mania: a report of 2 patients. J ECT. 2013;29(4):e59–e60. PubMed

- Hirjak D, Kubera KM, Wolf RC, et al. Going Back to Kahlbaum’s Psychomotor (And GABAergic) Origins: Is Catatonia More Than Just a Motor and Dopaminergic Syndrome? Schizophr Bull. 2020;46(2):272–285. PubMed CrossRef

- Fink M, Fink M. Delirious mania. Bipolar Disord. 1999;1(1):54–60. PubMed

- Restrepo-Martinez M, Ramirez-Bermudez J, Bayliss L, et al. Delirious mania as a frequent and recognizable neuropsychiatric syndrome in patients with anti- Nmdar encephalitis. Gen Hosp Psychiatry. 2020;64:50–55. PubMed CrossRef

- Beach SR, Luccarelli J, Praschan N, et al. Molecular and immunological origins of catatonia. Schizophr Res. 2024;263:169–177. PubMed CrossRef

- Levy E. Reinoso P, Shoaib H, et al. N-Methyl-D- Aspartate Receptor Encephalitis With Excited Catatonia: Literature Review and 2 Illustrative Cases, J Acad Consultation-Liaison Psychiatry. 2023;64(2):177-182. PubMed CrossRef

- Hansen MA, Bering R, Spanggård A, et al. Late-Onset Delirious Mania: Does It Ring a Bell? Bipolar Disord. 2024;26(4):331–334. PubMed CrossRef

- Heckers S, Walther S. Catatonia. N Engl J Med. 2023;389(19):1797–1802. PubMed CrossRef

- Karmacharya R, England ML, Ongür D, et al. Delirious mania: clinical features and treatment response. J Affect Disord. 2008;109(3):312–316. PubMed CrossRef

Enjoy this premium PDF as part of your membership benefits!