Cerebral amyloid angiopathy (CAA) is classified as a neurological illness; psychiatric symptoms such as cognitive impairment, personality change, behavioral problems, and depression are plausible clinical manifestations of CAA and may even dominate the clinical picture.1

Case Report

A 75-year-old woman from a rural area who was on regular treatment for hypertension for the past 10 years, with no past or family history of psychiatric illness or substance use, developed occasional third-person auditory hallucination with intact functionality for 10 months. Subsequently, she started having scenic visual hallucinations involving her deceased husband and son. She would describe them as seeing her husband riding a horse, approaching her, and interacting with her about different topics. She also started having second-person commenting auditory hallucinations and delusions of persecution. These symptoms gradually increased over the next 2 months and led to significant dysfunction. She consulted a psychiatrist and was prescribed aripiprazole 2 mg. After 5 days, risperidone 0.5 mg was added, as there was no improvement.

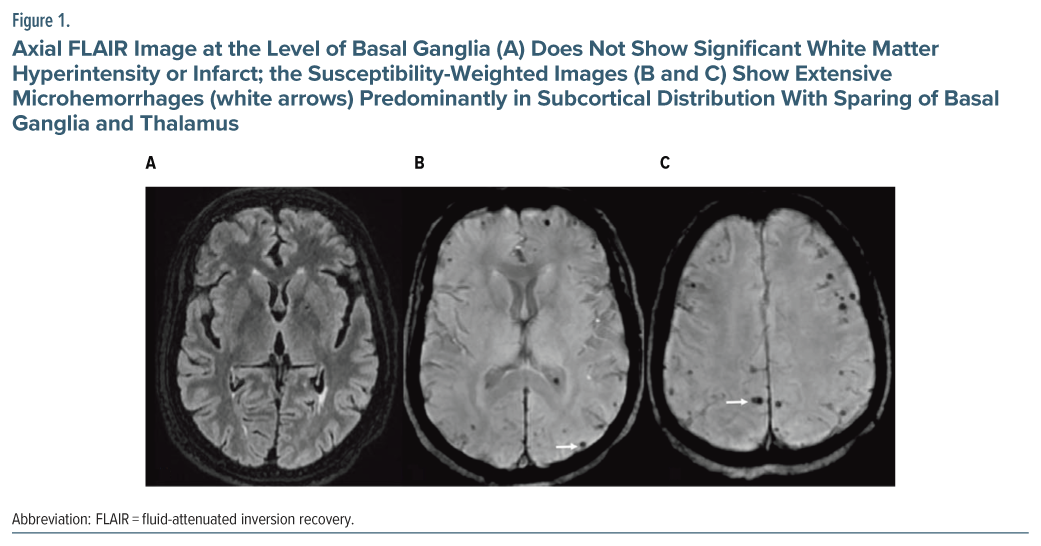

Non-contrast computed tomography of the head was done, which showed bilateral basal ganglia lacunar infarct. After 2 weeks, given no improvement, she was brought to our institute and was admitted. Her cognitive screening with the Montreal Cognitive Assessment was within normal limits.2 Neurological examination and hematological and biochemical investigations were normal. Magnetic resonance imaging of the brain (Figure 1) showed features suggestive of CAA with multiple innumerable foci of blooming on susceptibility-weighted imaging suggestive of microhemorrhages involving bilateral cerebral hemispheres in the subcortical location with sparing of the capsule-ganglionic region, thalamus, brain stem, and cerebellum. Mild diffuse cerebral atrophy was also noted. A few T2/fluid-attenuated inversion recovery hyperintensities were noted in bilateral periventricular regions suggestive of early small vessel ischemic changes, which fulfills the Boston criteria of probable CAA.3

She was diagnosed with psychotic syndrome secondary to CAA and stage 2 hypertension. Risperidone was continued and increased to 3 mg. However, as her serum prolactin level was found to be elevated (prolactin: 3,379 mIU/L), risperidone was tapered off, and aripiprazole was started and titrated to 20 mg. Her prolactin level normalized within 1 week. As there was no improvement in symptoms after 2 weeks, aripiprazole was cross-tapered with trifluoperazine 5 mg and increased to 15 mg over 1 week. Consultation liaison with the neurology department was done, aspirin 75 mg and atorvastatin 20 mg were added, and antihypertensive medications (telmisartan 40 mg, amlodipine 5 mg, and metoprolol 50 mg) were continued. With the above medications, the patient’s symptoms improved within 14 days of starting trifluoperazine. During the ward stay, the patient reported no visual hallucinations, and there was a reduction in the intensity of auditory hallucinations. She was discharged after 26 days of hospitalization. Within 2 months after discharge, her symptoms resolved entirely.

Discussion

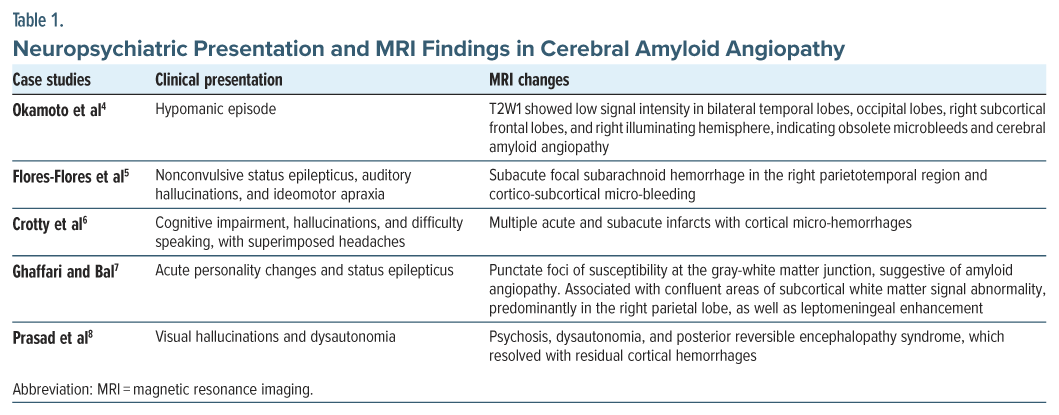

The index case differs from the earlier reported psychiatric manifestations with no other cognitive and neurological symptoms. Earlier reported cases include neuropsychiatric symptoms like confusion associated with auditory and visual hallucinations (possibly delirium), spontaneous resolution with supportive inpatient care, hypomania with cognitive impairment, and nonconvulsive status epilepticus, auditory hallucinations, and ideomotor apraxia.4,5 CAA can also present with headache, cognitive impairment, aphasia, acute personality changes, and dysautonomia (Table 1).6–8 Although psychotic illnesses are not commonly reported in CAA, there is some evidence for the association of advanced CAA with psychosis in Alzheimer’s disease.9

Psychosis can be an initial symptom of CAA in the absence of any cognitive impairment or neurological sequelae (infarct, seizure, etc). Thus, new-onset psychotic symptoms in geriatric patients should warrant evaluation for determining underlying CAA, especially in patients with a history of hypertension and visual hallucinations. Early identification may provide an avenue for the prevention of further neuropsychiatric sequelae.

Article Information

Published Online: August 14, 2025. https://doi.org/10.4088/PCC.25cr03964

© 2025 Physicians Postgraduate Press, Inc.

Prim Care Companion CNS Disord 2025;27(4):25cr03964

Submitted: March 12, 2025; accepted June 3, 2025.

To Cite: Raj AB, Rajpurohit SS, Tiwari S, et al. Cerebral amyloid angiopathy presenting as a psychotic disorder. Prim Care Companion CNS Disord 2025;27(4):25cr03964.

Affiliations: Department of Psychiatry, All India Institute of Medical Sciences, Jodhpur, Rajasthan, India (Raj, Rajpurohit, Swami); Department of Diagnostic and Interventional Radiology, All India Institute of Medical Sciences, Jodhpur, India (Tiwari).

Corresponding Author: Akshaya B. Raj, MBBS, MD, Department of Psychiatry, All India Institute of Medical Sciences, Basni Industrial Area Phase-2, Jodhpur, India ([email protected]).

Relevant Financial Relationships: None.

Funding/Support: None.

ORCID: Akshaya B. Raj: https://orcid.org/0009-0008-5770-7361

References (9)

- Gahr M, Nowak DA, Connemann BJ, et al. Cerebral amyloidal angiopathy-a disease with implications for neurology and psychiatry. Brain Res. 2013;1519:19–30. PubMed CrossRef

- Nasreddine ZS, Phillips NA, Bédirian V, et al. The Montreal Cognitive Assessment, MoCA: a brief screening tool for mild cognitive impairment. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2005;53(4):695–699. PubMed CrossRef

- Greenberg SM, Charidimou A. Diagnosis of cerebral amyloid angiopathy: evolution of the Boston criteria. Stroke. 2018;49(2):491–497. PubMed CrossRef

- Okamoto N, Ikenouchi A, Seki I, et al. Cerebral amyloid angiopathy with a hypomanic episode treated with valproic acid. Cureus. 2021;13(7):e16411. PubMed CrossRef

- Flores-Flores A, Sueiras-Gil M, Toledo M, et al. Estado de mal epiléptico no convulsivo secundario a hemorragia subaracnoidea como forma de presentación de una angiopatía amiloide cerebral [Non-convulsive status epilepticus secondary to subarachnoid haemorrhage as the presenting symptom of a cerebral amyloid angiopathy]. Rev Neurol. 2010;50(5):279–282. PubMed

- Crotty GF, McKee K, Saadi A, et al. Clinical pathologic case report: a 70-year-old man with inflammatory cerebral amyloid angiopathy causing headache, cognitive impairment, and aphasia. J Clin Neurosci. 2018;49:71–75. PubMed CrossRef

- Ghaffari L, Bal T. An unusual presentation of acute psychosis in an elderly patient with inflammatory cerebral amyloid angiopathy (1197). Neurology. 2020;94(suppl 15):1197. CrossRef

- Prasad A, Sharma S, Schmidt E, et al. Cerebral amyloid angiopathy presenting as new onset refractory status epilepticus (NORSE), complicated by psychosis, dysautonomia and posterior reversible encephalopathy syndrome (PRES). Neurology. 2016;86(suppl 16):P6–P219.

- Vik-Mo AO, Bencze J, Ballard C, et al. Advanced cerebral amyloid angiopathy and small vessel disease are associated with psychosis in Alzheimer’s disease. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2019;90(6):728–730. PubMed CrossRef

Enjoy this premium PDF as part of your membership benefits!