Cerebrotendinous xanthomatosis (CTX), a rare autosomal recessive disorder from CYP27A1 (cytochrome P450 family 27 subfamily A member 1) mutations,1 causes deficient sterol 27-hydroxylase, impairing bile acid synthesis and leading to abnormal cholestanol/cholesterol accumulation in the brain, tendons, and eyes.2 Variable clinical presentation includes early bilateral cataracts (childhood/adolescence) and tendon xanthomas (Achilles). Progressive neurological dysfunction (cerebellar ataxia, spasticity) is a hallmark. Psychiatric manifestations can delay diagnosis. Psychiatric symptoms3 may appear later. The insidious onset often causes diagnostic delays, hindering early chenodeoxycholic acid (CDCA) treatment benefits.2,3 This case highlights diagnostic challenges in patients with prominent psychiatric and cognitive symptoms leading to a CTX diagnosis in their 50s.

Case Report

A 51-year-old woman with a past medical history of neonatal jaundice requiring neonatal intensive care unit admission, frequent childhood diarrhea, hypertension, and bilateral glaucoma presented to the outpatient psychiatry department. At age 19 years, she had undergone surgery for bilateral cataracts. Her presenting complaints spanned 8 months and included forgetfulness, diminished attention, frequent anger outbursts, irritability, disturbed sleep, and discomfort in her left lower limb upon walking. These symptoms had notably worsened in the 2 weeks prior to presentation. Initial cognitive assessments were as follows:

- Attention (Digit Span): 5 forward digits, 3 backward digits

- Mini-Mental State Examination (MMSE)4: 26/30

- Montreal Cognitive Assessment (MoCA)5: 23/30, indicating visuospatial deficits

- Frontal Assessment Battery (FAB)6: 14/18

- Neuropsychiatric Inventory7: revealed agitation and irritability (severity 1, distress 3).

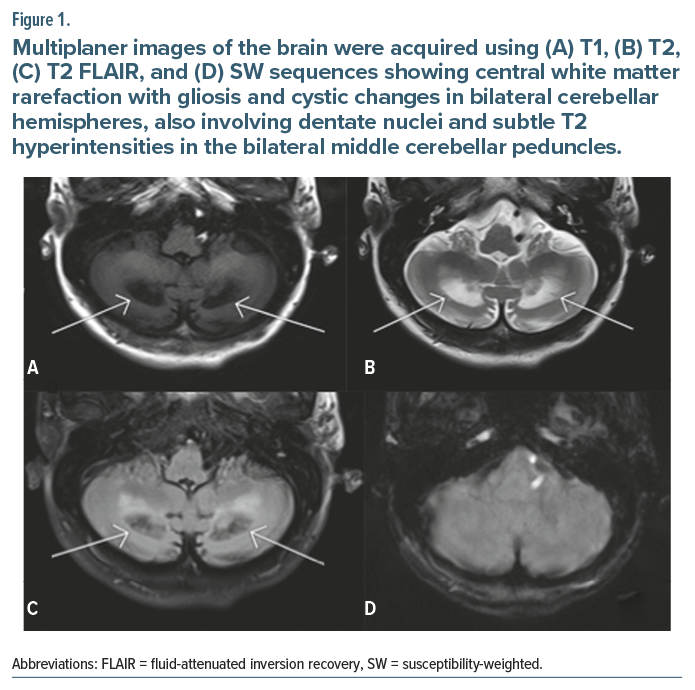

The findings led to a mild neurocognitive disorder diagnosis. The central nervous system examination showed impaired Romberg’s sign, tandem walking difficulty, and hyperreflexia. Two days prior, she had been hospitalized with fever/vomiting. Magnetic resonance imaging findings revealed central white matter rarefaction with gliosis and cystic changes in bilateral cerebellar hemispheres (Figure 1), raising suspicion for CTX. CTX was confirmed by CYP27A1 mutation on next-generation sequencing and elevated plasma cholestanol (70.8 μmol/L), with slightly elevated total cholesterol (330 mg/dL). CDCA (250 mg 3 times/d) was started, and the medication regimen for behavioral and cognitive symptoms was adjusted to olanzapine 2.5 mg at night, donepezil 5 mg in the morning, and memantine 5 mg at night.

On subsequent follow-ups, the patient demonstrated overall improvement in irritability, anger outbursts, forgetfulness, and concentration on household activities. Her plasma cholestanol level decreased to 57.2 μmol/L. She also reported significant improvement in walking discomfort. Repeat cognitive testing demonstrated improved scores across attention (Digit Span: 6 forward, 4 backward), MMSE (28/30), MoCA (26/30), and FAB (16/18).

Discussion

This case highlights a middle-aged woman whose initial presentation of psychiatric and cognitive difficulties led to a mild neurocognitive disorder diagnosis. However, her history of neonatal jaundice, childhood diarrhea, and juvenile cataracts and classic early CTX signs3 should have raised earlier suspicion. The diagnostic delay until age 51 is common, with many CTX patients diagnosed in adulthood after significant neurological or psychiatric symptoms develop. Psychiatric manifestations often complicate diagnosis. The observed cognitive decline, fitting mild neurocognitive disorder criteria, is a known CTX neurological complication due to cholestanol accumulation.

Neuroimaging revealed white matter and cerebellar changes consistent with CTX. Genetic analysis confirmed a CYP27A1 mutation, the gold standard, alongside elevated cholestanol. CDCA therapy, the primary treatment,1 reduced cholestanol and improved her psychiatric symptoms, cognition, and gait.1 This aligns with evidence for early CDCA benefits. However, late-diagnosed patients may still deteriorate.3,8 Symptomatic medications also likely contributed to her improvement. Mustafa et al9 reveal a critical issue in India: Scarce CDCA access often leads to CTX patients receiving ineffective ursodeoxycholic acid.

Regarding the potential for newborn screening, CTX is not routinely included in standard panels due to its rarity and the lack of cost-effective, high-throughput screening methods. However, targeted screening for CYP27A1 mutations or elevated cholestanol levels in neonates with a family history or suggestive symptoms (eg, neonatal jaundice) could be feasible, as early CDCA treatment significantly improves outcomes.2,8

This case emphasizes the need for greater CTX awareness. Early clues like unexplained juvenile cataracts and chronic diarrhea should prompt consideration of CTX and appropriate testing. Early diagnosis and treatment are crucial to limit irreversible neurological damage and improve outcomes.

Article Information

Published Online: October 30, 2025. https://doi.org/10.4088/PCC.25cr04001

© 2025 Physicians Postgraduate Press, Inc.

Prim Care Companion CNS Disord 2025;27(5):25cr04001

Submitted: February 11, 2025; accepted July 17, 2025.

To Cite: Anand A, Garg S, Dhyani M, et al. Cerebrotendinous xanthomatosis: unraveling prominent neuropsychiatric symptoms and mild cognitive impairment with subsequent clinical improvement. Prim Care Companion CNS Disord 2025;27(5):25cr04001.

Author Affiliations: Department of Psychiatry, Shri Guru Ram Rai Institute of Medical and Health Sciences, Dehradun, India (Anand, Garg, Dhyani); Department of Psychiatry, Hi-Tech Medical College, Bhubaneswar, India (Pattojoshi).

Corresponding Author: Shobit Garg, MD, DPM, Department of Psychiatry, Shri Guru Ram Rai Institute of Medical and Health Sciences, Shri Guru Ram Rai University, Dehradun, Uttarakhand 248001 India ([email protected]).

Relevant Financial Relationships: None.

Funding/Support: None.

Patient Consent: Informed consent was obtained from the patient to publish the case report, and information has been de-identified to protect patient anonymity.

References (9)

- Federico A, Dotti MT, Galli G. Cerebrotendinous xanthomatosis. Neurology. 1999;53(10):2180–2182.

- Minderhoud JM, van den Bogaert GH, Barth PG, et al. Cerebrotendinous xanthomatosis: diagnosis and management. Eur Neurol. 1992;32(3):129–140.

- Nóbrega C, Brasil S, Mendes R, et al. Cerebrotendinous xanthomatosis: a challenging diagnosis in adult psychiatry. BMC Psychiatry. 2022;22(1):1–6. PubMed

- Folstein MF, Folstein SE, McHugh PR. “Mini-mental state”: a practical method for grading the cognitive state of patients for the clinician. J Psychiatr Res. 1975;12(3):189–198. PubMed CrossRef

- Nasreddine ZS, Phillips NA, Bédirian V, et al. The Montreal Cognitive Assessment, MoCA: a brief screening tool for mild cognitive impairment. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2005;53(4):695–699. PubMed CrossRef

- Dubois B, Slachevsky A, Litvan I, et al. The FAB: a frontal assessment Battery at bedside. Neurology. 2000;55(11):1621–1626. PubMed CrossRef

- Cummings JL, Mega M, Gray K, et al. The Neuropsychiatric Inventory: comprehensive assessment of psychopathology in dementia. Neurology. 1994;44(12):2308–2314. PubMed CrossRef

- Duell PB, Salen G, Eichler FS, et al. Diagnosis, treatment, and clinical outcomes in 43 cases with cerebrotendinous xanthomatosis. J Clin Lipidol. 2018;12(5):1169–1178. PubMed CrossRef

- Mustafa F, Km T, Agarwal A, et al. A case series of nine patients with cerebrotendinous xanthomatosis from India and a systematized review of Indian literature. Parkinsonism Relat Disord. 2025;133:107331. PubMed CrossRef

Enjoy this premium PDF as part of your membership benefits!