Abstract

Background: To examine the possible impact of daylight duration on the efficacy of repetitive transcranial magnetic stimulation (rTMS) in patients with treatment-resistant depression (TRD).

Methods: A retrospective cohort study of 151 patients with TRD undergoing rTMS was conducted. The patient data were collected over multiple years from August 2018 to August 2025. Depression severity was assessed using the Patient Health Questionnaire-9 (PHQ-9) and Hamilton Depression Rating Scale (HDRS) before and after treatment. Patients were categorized into 3 groups: responders, remitters, and nonresponders. Responders were defined by a decrease in PHQ-9 or HDRS score by 50% or more. Remitters were defined by achieving a PHQ-9 score <5 or HDRS score <7. Nonresponders were defined by a change in these scores <50%. Average daylight duration for each individual patient was calculated throughout treatment and compared between groups.

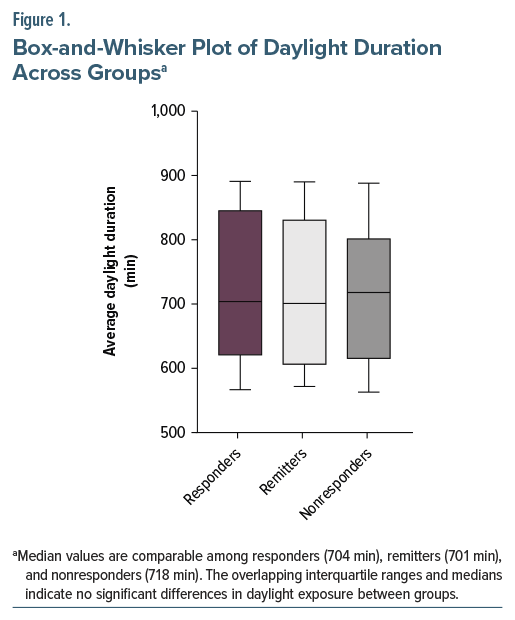

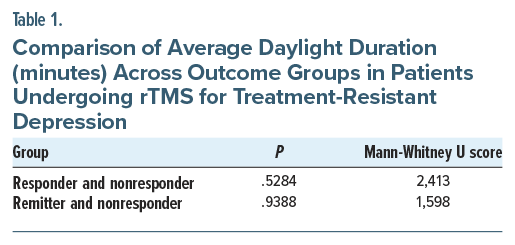

Results: The median average duration of daylight in the responder group (n=99) was 704 minutes. The median average duration of daylight in the remitter group (n=62) was 701 minutes, whereas the median average duration of daylight in nonresponders (n=52) was 718 minutes. The Mann-Whitney U test showed no statistical difference in the average daylight duration between the responder and nonresponder groups. Similarly, there was no statistical difference in the average daylight duration between the remitter and nonresponder groups.

Conclusion: Based on these findings, daylight duration does not seem to affect rTMS outcomes (response or remission) in patients with TRD. This is reassuring, and if confirmed by future studies, it would mean that rTMS can be delivered at any time of the year without affecting efficacy.

Prim Care Companion CNS Disord 2026;28(1):25m04079

Author affiliations are listed at the end of this article.

Major depressive disorder (MDD) is a severe, disabling, and in most cases recurrent condition, with a prevalence rate of 7.1%.1 Symptoms of MDD vary between individuals, and the combinations of symptoms are vast. This variability contributes to a broad spectrum of pharmacologic and nonpharmacologic treatments. Standard treatment with pharmacotherapy or psychotherapy is often ineffective and not tolerated in a considerable portion of patients.2

Treatment-resistant depression (TRD) refers to MDD patients who do not respond to multiple courses of different antidepressants.3 This further complicates the treatment of MDD. Better treatments are in great demand, and the need to optimize and build on the treatments already available is apparent. Noninvasive brain stimulation (NIBS) offers an alternative in the treatment of TRD. NIBS refers to stimulating neurons in the brain without surgical procedures or anesthesia. One of these methods is repetitive transcranial magnetic stimulation (rTMS), which delivers magnetic pulses that penetrate the brain painlessly, stimulate underlying tissue, and modulate neuronal activity in targeted cortical regions. rTMS is approved by the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) for the treatment of moderate to severe MDD in patients who have failed 1 or more medications and/or psychotherapy.4–8

In evidence-based guidelines on the therapeutic use of rTMS, the effectiveness of this modality in depression was judged to be at a level A.9 In naturalistic settings, the response and remission rates can be up to 58% and 37%, respectively.10 However, there is a lot of room for improvement by optimizing the treatment itself. One option is to assess the influence of brain-state dependence on rTMS outcomes.11 It is asserted that the state of the targeted cortical region during the application of stimulation dramatically influences the effects. In other words, the NIBS effects depend not only on the parameters of external stimulation but also on the underlying state of the stimulated region or network. For instance, the TMS-triggered response is very different during the state of wakefulness versus sleep, anesthesia, and vegetative state.12 Provocation procedure in the treatment of obsessive-compulsive disorder is one clinically useful example of how preactivation of the circuit involved in the disorder leads to improved outcomes with treatment.13

Based on this information, clinicians may combine rTMS with other treatment modalities such as psychotherapy for depression,14 exposure therapy for posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD)15 and acrophobia,16 and cognitive processing therapy for PTSD,17 as well as positive and negative cognitive reactivation,18 aerobic exercise,19 music,20 and bright light therapy (BLT).21,22 The influence of natural daylight exposure on rTMS outcomes in TRD has not been studied. Yet, it cannot be underestimated, as this could be one of those parameters that can influence the underlying brain state. This study investigates if the duration of daylight modulates rTMS outcomes in TRD.

METHODS

A sample of 151 patients with TRD who completed rTMS at a single medical center was included in the study. The patient data were collected over multiple years from August 2018 to August 2025. All patients in the study had TRD with the failure of 4 or more antidepressant medications of at least 2 different classes and unsuccessful psychotherapy.

rTMS was delivered using H1-coil (BrainsWay Deep TMS) to the left dorsolateral prefrontal cortex according to the FDA-approved protocol.5 18-Hz stimulation was delivered in 2-second trains, with 20 seconds between trains, for a total of 55 trains (1,980 pulses) delivered over 20 minutes. The maximum intensity of the stimulation was 120% of the motor threshold. The initial treatment was delivered daily for 6 weeks, and the taper was started at week 7. Three sessions were delivered at week 7, 2 sessions at week 8, and 1 session at week 9. rTMS was discontinued after week 9.

Depression severity and response were assessed using the Patient Health Questionnaire-9 (PHQ-9) and the Hamilton Depression Rating Scale (HDRS). The PHQ-9 is a 9-item self-report instrument aligned with Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fifth Edition, criteria, while the HDRS is a 17-item clinician-administered scale.23,24 Baseline PHQ-9 and HDRS scores were collected before rTMS initiation and repeated at the end of treatment. The total patient population was categorized into 3 groups: responder group, remitter group, and nonresponder group, based on response to rTMS.

We defined response as a decrease in PHQ-9 or HDRS score by 50% or more and remission as achieving a PHQ-9 score <5 or HDRS score <7 within the treatment duration. Patients who had a score change of <50% were defined as nonresponders, as is consensus on the use of these scales.25,26

All patients had completed a full course of rTMS treatment. As long as rTMS was safe to administer, no exclusion criteria were used in terms of medical or psychiatric comorbidities. The clinic that provided data followed the most recent consensus recommendations with regard to screening for safety and treatment delivery when selecting patients.7

The average duration of daylight during each patient’s treatment period was calculated using open-access data from the US Naval Observatory, which provides daylight and darkness duration for specified dates of any year and for a specified location. The location used for this study was that of the rTMS treatment facility in Chambersburg, Pennsylvania. The average duration of daylight was calculated for each group. The data were then tested for normality using the Shapiro-Wilk test and compared using the Mann-Whitney U test with GraphPad Prism version 10.

RESULTS

The median average duration of daylight was similar across outcome groups: responders (n= 99) had 704 minutes, remitters (n=62) had 701 minutes, and nonresponders (n=52) had 718 minutes. The Shapiro-Wilk test for normality indicates a non-Gaussian distribution in all groups. The Mann-Whitney U test showed no statistical difference in average daylight duration between responder and nonresponder groups. Similarly, there was no statistical difference in the average daylight duration between remitter and nonresponder groups (Figure 1 and Table 1).

DISCUSSION

Use of light for depression dates back to the beginning of civilization. It has long been understood that there is an interplay between seasonal variations in light exposure and depression since the first description of the syndrome of seasonal affective disorder (SAD) and light therapy in the seminal paper by Rosenthal et al.27 Since then, BLT has become a widely used treatment method for SAD as well as nonseasonal depressive disorder like MDD, with or without medications.28 If daylight exposure has effects on brain-state dependency, it can influence response to rTMS.

In neuroscience research, exposure to daylight is understood to mitigate depressive symptoms through multiple biological mechanisms. The human retina contains photoreceptor rods and cones that transform light into electrical signals. They project to retinal ganglion cells (RGCs), which output these signals to the brain. About 45% of these cells contain photopigment melanopsin, which are called intrinsically photosensitive RGCs (ipRGCs). The discovery of projections of ipRGCs to brain mood centers has redefined the understanding of light-mediated mood regulation. Involvement of sleep and circadian rhythms in the etiology of mood disorders involves direct and indirect pathways originating from ipRGCs. Indirect pathways have long been studied and are well defined. Signals from the retinal ipRGCs travel along the retinohypothalamic tract to the suprachiasmatic nucleus (SCN) of the anterior hypothalamus. In addition to downstream targets like the pineal gland, which regulates circadian rhythm, SCN drives rhythms in the locus ceruleus, amygdala, lateral habenula, and ventral tegmental area (VTA). Together, these structures constitute part of neural circuits implicated in depression. The direct pathway has been defined more recently, and it involves ipRGC projections directly to the medial amygdala and lateral habenula, which are implicated in mood regulation. The amygdala in turn projects to the VTA and hippocampus, 2 brain regions known to have a role in depression. The lateral habenula projects to the VTA and the raphe nucleus and forms a node of connection between the limbic nuclei, hypothalamic brain regions, and brain stem monoamine neurons.21,29

Given the biological interplay between light exposure and neurohormonal alterations, we can postulate that the duration of daylight in a particular course of rTMS may change outcomes and is therefore worth studying. The current study specifically examined whether the hours of daylight during the course of treatment of an individual had any effect on their ability to achieve response or remission.

Analyses revealed no statistical difference in the average duration of daylight between groups. Based on these findings, daylight duration does not seem to affect rTMS outcomes (response or remission) in patients with TRD. This is reassuring, and if confirmed by future studies, it would mean that rTMS can be delivered at any time of the year without affecting efficacy.

Limitations

This was a single-site study with 1 protocol. Possible variables that could affect the responsiveness of rTMS, such as severity of depression, concomitant medications, stress levels, or other environmental factors that might also vary seasonally, were not accounted for. Finally, average minutes of daylight might not fully capture its impact. The time of exposure (morning vs evening) and intensity (direct vs indirect sunlight) could be more relevant than just total minutes. The main goal of the study was to compare well-defined groups of responders, remitters, and nonresponders, and dropouts were excluded from analysis because they could not be categorized into any of the 3 groups, as they did not finish the full course of treatment.

CONCLUSION

This is the first study, to the best of our knowledge, examining the possible effects of daylight duration on rTMS outcomes for depression. The findings showed no statistically significant difference in average daylight duration between individuals who achieved remission, who showed response, and who did not respond to treatment. More research is needed before firm conclusions can be drawn.

We hope our study sparks interest in further research, as it addresses a relevant clinical question. We hope future studies will prospectively examine the relationship between daylight duration and rTMS outcomes under controlled treatment conditions and account for variables.

Article Information

Published Online: February 3, 2026. https://doi.org/10.4088/PCC.25m04079

© 2026 Physicians Postgraduate Press, Inc.

Submitted: September 10, 2025; accepted November 25, 2025.

To Cite: Mania I, Kapoor A, Alavidze M, et al. Effect of daylight duration on outcomes of repetitive transcranial magnetic stimulation in treatment-resistant depression. Prim Care Companion CNS Disord 2026;28(1):25m04079.

Author Affiliations: Tbilisi State Medical University, Tbilisi, Georgia (Alavidze, Kapoor); Keystone Health, Chambersburg, Pennsylvania (Faruqui, Mania); Drexel University College of Medicine, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania (Faruqui).

Corresponding Author: Zeeshan Faruqui, MD, DFAPA, Keystone Health, Chambersburg, Pennsylvania ([email protected]).

Financial Disclosure: None.

Funding/Support: None.

Acknowledgment: The authors would like to acknowledge the contribution of Emily Landis, LPN, in data collection and patient care. Ms Landis has no financial relationships to disclose.

ORCID: Mariam Alavidze: https://orcid.org/0009-0001-3841-495X; Aaryan Kapoor: https://orcid.org/0009-0006-2850-6590; Irakli Mania: https://orcid.org/0009-0003-3777-013X; Zeeshan Faruqui: https://orcid.org/0000-0002-4070-1042

Clinical Points

- Daylight duration does not seem to affect repetitive transcranial magnetic stimulation (rTMS) outcomes (response or remission) in patients with treatment-resistant depression, suggesting that rTMS can be delivered at any time of the year without affecting efficacy.

- Future studies should prospectively examine the relationship between daylight and rTMS outcome under controlled treatment conditions and account for variables.

References (29)

- NIMH. Prevalence of Major Depressive Episode Among Adults. Online; 2017. https://www.nimh.nih.gov/health/statistics/major-depression.shtml

- Rush AJ, Trivedi MH, Wisniewski SR, et al. Acute and longer-term outcomes in depressed outpatients requiring one or several treatment steps: a STAR*D report. Am J Psychiatry. 2006;163(11):1905–1917. PubMed CrossRef

- Fava M. Diagnosis and definition of treatment-resistant depression. Biol Psychiatry. 2003;53(8):649–659. PubMed CrossRef

- O’Reardon JP, Solvason HB, Janicak PG, et al. Efficacy and safety of transcranial magnetic stimulation in the acute treatment of major depression: a multisite randomized controlled trial. Biol Psychiatry. 2007;62(11):1208–1216. PubMed CrossRef

- Levkovitz Y, Isserles M, Padberg F, et al. Efficacy and safety of deep transcranial magnetic stimulation for major depression: a prospective multicenter randomized controlled trial. World Psychiatry. 2015;14(1):64–73. PubMed CrossRef

- Blumberger DM, Vila-Rodriguez F, Thorpe KE, et al. Effectiveness of theta burst versus high-frequency repetitive transcranial magnetic stimulation in patients with depression (THREE-D): a randomised non-inferiority trial. Lancet. 2018;391(10131):1683–1692. PubMed CrossRef

- McClintock SM, Reti IM, Carpenter LL, et al. Consensus recommendations for the clinical application of repetitive transcranial magnetic stimulation (rTMS) in the treatment of depression. J Clin Psychiatry. 2018;79(1):16cs10905. PubMed CrossRef

- Tendler A, Goerigk S, Zibman S, et al. Deep TMS H1 Coil treatment for depression: results from a large post marketing data analysis. Psychiatry Res. 2023;324:115179. PubMed CrossRef

- Lefaucheur JP, Aleman A, Baeken C, et al. Evidence-based guidelines on the therapeutic use of repetitive transcranial magnetic stimulation (rTMS): an update (2014-2018). Clin Neurophysiol. 2020;131(2):474–528. PubMed CrossRef

- Carpenter LL, Janicak PG, Aaronson ST, et al. Transcranial magnetic stimulation (TMS) for major depression: a multisite, naturalistic, observational study of acute treatment outcomes in clinical practice. Depress Anxiety. 2012;29(7):587–596. PubMed CrossRef

- Sack AT, Paneva J, Küthe T, et al. Target engagement and brain state dependence of transcranial magnetic stimulation: implications for clinical practice. Biol Psychiatry. 2024;95(6):536–544. PubMed CrossRef

- Sarasso S, Rosanova M, Casali AG, et al. Quantifying cortical EEG responses to TMS in (un)consciousness. Clin EEG Neurosci. 2014;45(1):40–49. PubMed CrossRef

- Carmi L, Alyagon U, Barnea-Ygael N, et al. Clinical and electrophysiological outcomes of deep TMS over the medial prefrontal and anterior cingulate cortices in OCD patients. Brain Stimul. 2018;11(1):158–165. PubMed CrossRef

- Donse L, Padberg F, Sack AT, et al. Simultaneous rTMS and psychotherapy in major depressive disorder: clinical outcomes and predictors from a large naturalistic study. Brain Stimul. 2018;11(2):337–345. PubMed CrossRef

- Fryml LD, Pelic CG, Acierno R, et al. Exposure therapy and simultaneous repetitive transcranial magnetic stimulation: a controlled pilot trial for the treatment of posttraumatic stress disorder. J Ect. 2019;35(1):53–60. PubMed CrossRef

- Herrmann MJ, Katzorke A, Busch Y, et al. Medial prefrontal cortex stimulation accelerates therapy response of exposure therapy in acrophobia. Brain Stimul. 2017;10(2):291–297. PubMed CrossRef

- Kozel FA, Motes MA, Didehbani N, et al. Repetitive TMS to augment cognitive processing therapy in combat veterans of recent conflicts with PTSD: a randomized clinical trial. J Affect Disord. 2018;229:506–514. PubMed CrossRef

- Isserles M, Rosenberg O, Dannon P, et al. Cognitive-emotional reactivation during deep transcranial magnetic stimulation over the prefrontal cortex of depressive patients affects antidepressant outcome. J Affect Disord. 2011;128(3):235–242. PubMed CrossRef

- Ross RE, VanDerwerker CJ, Newton JH, et al. Simultaneous aerobic exercise and rTMS: feasibility of combining therapeutic modalities to treat depression. Brain Stimul. 2018;11(1):245–246. PubMed CrossRef

- Mania I, Kaur J. Music combined with transcranial magnetic stimulation for the treatment of depression. IAMM: Music and Medicine 2020:253–257. CrossRef

- Mania I, Kaur J. Bright light therapy and rTMS; novel combination approach for the treatment of depression. Brain Stimul. 2019;12(5):1338–1339. PubMed CrossRef

- Barbini B, Attanasio F, Manfredi E, et al. Bright light therapy accelerates the antidepressant effect of repetitive transcranial magnetic stimulation in treatment resistant depression: a pilot study. Int J Psychiatry Clin Pract. 2021;25(4):375–377. PubMed CrossRef

- Kroenke K, Spitzer RL, Williams JB. The PHQ-9: validity of a brief depression severity measure. J Gen Intern Med. 2001;16(9):606–613. PubMed CrossRef

- Hamilton M. A rating scale for depression. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 1960;23(1):56–62. PubMed CrossRef

- Coley RY, Boggs JM, Beck A, et al. Defining success in measurement-based care for depression: a comparison of common metrics. Psychiatr Serv. 2020;71(4):312–318. PubMed CrossRef

- Frank E, Prien RF, Jarrett RB, et al. Conceptualization and rationale for consensus definitions of terms in major depressive disorder. Remission, recovery, relapse, and recurrence. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1991;48(9):851–855. PubMed CrossRef

- Rosenthal NE, Sack DA, Gillin JC, et al. Seasonal affective disorder. A description of the syndrome and preliminary findings with light therapy. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1984;41(1):72–80. PubMed CrossRef

- Golden RN, Gaynes BN, Ekstrom RD, et al. The efficacy of light therapy in the treatment of mood disorders: a review and meta-analysis of the evidence. Am J Psychiatry. 2005;162(4):656–662. PubMed CrossRef

- LeGates TA, Fernandez DC, Hattar S. Light as a central modulator of circadian rhythms, sleep and affect. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2014;15(7):443–454. PubMed CrossRef

Enjoy this premium PDF as part of your membership benefits!