Toe walking, or equinus gait, is a gait abnormality most observed in children and typically considered idiopathic. It may also be associated with neuropsychiatric conditions, developmental delays, or muscle tightness.1 In adults, however, toe walking is more often secondary to underlying pathology, often serving as a compensatory mechanism in the context of upper motor neuron (UMN) injuries characterized by increased muscle tone, spasticity, and an overactive stretch reflex that leads to stiff muscles and a plantar flexed foot.2 In the gait cycle, the stance (60% of the cycle) and swing (40% of the cycle) phases rely on multifaceted kinetic dynamics that can be easily disrupted by injury or pathology, often doubling energy expenditure.3 Toe walking, associated with prolonged ankle plantar flexor nerve activity, requires more neuromuscular effort.4 However, toe walking has the advantage of lower peak plantar flexor forces, becoming useful for relieving neuropathic pain.4

The clinical presentation of motor neuron lesions can be a useful diagnostic tool. Lower motor neuron (LMN) lesions typically manifest with muscular atrophy, decreased or absent deep tendon reflexes, flaccid paralysis, fasciculations, and cavus foot deformities.5 In contrast, UMN lesions present with spastic paralysis, hyperreflexia, muscular hypertrophy, and a positive Babinski sign.6

While the literature surrounding toe walking often focuses on UMN etiologies, such as poststroke spasticity, LMN causes remain underrecognized. This report aims to broaden the differential diagnosis of adult toe walking by presenting a unique case in which toe walking, typically associated with UMN pathology, appears instead to be a compensatory response to LMN dysfunction. This introduces a novel perspective to the existing literature, as its occurrence in the context of LMN pathology remains underrecognized.

Case Report

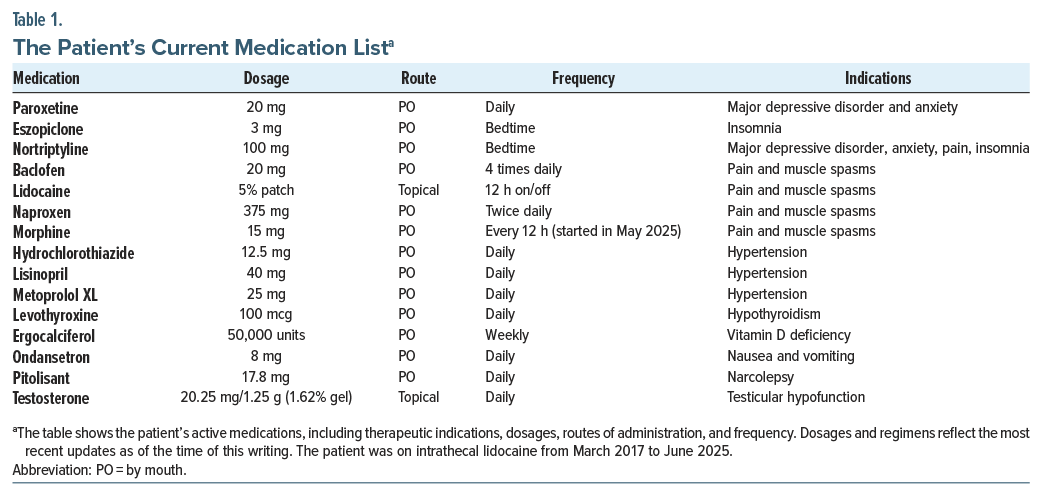

A 60-year-old black man with a history of an incidental left basal ganglia infarct noted on magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) in January 2022 presented to the Pain Management and Rehabilitation Clinic for evaluation of chronic left-sided posterior leg pain. The pain was described as radiating up the left leg from the foot and was specifically worsened by left heel strike. There was no associated sciatica or lumbar spine discomfort. To manage this pain, the patient reported adopting a toe-walking gait to avoid heel contact and reduce symptoms. His medical history is significant for Arnold-Chiari type I malformation, obesity (body mass index: 37 kg/m2), hypertension, testicular hypofunction, hypothyroidism, degenerative disc disease, recurrent major depressive disorder (MDD) with anxiety, polyneuropathy, fibromyalgia, and narcolepsy. He developed central pain syndrome approximately 1 year after his incidental stroke finding on MRI and prolonged grief disorder stemming from the death of his wife in 2023. The patient had opioid use disorder and was taking morphine that was prescribed by his nurse practitioner beginning in May 2025. Current daily medications include those listed in Table 1.

On physical examination, the patient exhibited a resting tremor in the right hand. Reflexes revealed hyperreflexia (3+) in the right triceps without clonus, while all other reflexes were symmetric. Babinski sign was negative bilaterally. Muscle strength testing showed full strength (5/5) in the right upper and lower extremities but notable weakness (3/5) on the left side.

Spasticity was observed in the lower right back. Sensory examination showed preserved light touch in all extremities, except for increased sensitivity over the distribution of the right deep peroneal nerve. Cranial nerves II through XII were intact, and coordination was preserved.

Musculoskeletal findings included left foot supination, extension of the second toe, hypertrophy of the left-sided flexor muscles, and myofascial tenderness in the cervical and thoracic paraspinal regions. The patient’s gait was unsteady and demonstrated a left-sided equinus pattern.

Routine laboratory studies were obtained and showed several important findings. Creatinine was elevated at 1.46 mg/dL (normal range, 0.6–1.2 mg/dL). Estimated glomerular filtration rate was reduced at 55 mL/ min/1.73 m2 (>60 mL/min/1.73 m2). This was consistent with chronic kidney disease stage 3a. Complete blood count showed mild anemia. Hemoglobin was low at 10.6 g/dL (range, 13.5–17.5 g/dL). Mean corpuscular hemoglobin and mean corpuscular hemoglobin concentration were low at 25 and 29 (27–33 pg and 32–36 g/dL), respectively. Red cell distribution width was high at 15.9% (11.5%–14.5%). These findings suggested possible iron deficiency. Vitamin B12 was elevated above 2,000 pg/mL (200–900 pg/mL). This may also have reflected supplementation. Normal laboratory values include testosterone, vitamin D, electrolytes, liver enzymes, glucose, prostate-specific antigen, prolactin, and insulin-like growth factor 1.

A computed tomography (CT) scan of the spine revealed multilevel bulging of the lumbar annulus and a left lateral L4–L5 disc herniation with moderate left foraminal narrowing. These findings may correspond to L5 nerve compression and explain the observed left-sided ankle dorsiflexion weakness. An electromyography (EMG) performed 1 month after the initial visit showed findings consistent with sensorimotor polyneuropathy, although interpretation was limited by patient-reported pain. Sensory responses were unobtainable, and the left tibial motor response was absent. There was no evidence of myopathy. A plain radiograph of the calcaneus was ordered to assess for underlying osseous pathology. A left aircast walking boot was provided to the patient, which resulted in immediate pain relief during ambulation. An order was placed for a custom ankle-foot orthosis to support gait stability and further reduce pain. A diagnostic left tibial nerve block was recommended to evaluate for possible tarsal tunnel syndrome. Depending on the results of the nerve block, cryoneurolysis was proposed as a potential next step in pain management.

Discussion

This case highlights the diagnostic complexity involved in evaluating gait abnormalities and motor weakness, particularly when multiple neurologic conditions coexist. The patient initially presented with toe walking and lower limb weakness, which, in the context of a prior left basal ganglia stroke, prompted concern for a UMN etiology such as poststroke spasticity. This interpretation was reinforced by imaging findings and a history of tremors and weakness, consistent with prior central nervous system insult.

However, a closer clinical examination revealed a right-sided weakness with no signs of spasticity. Specifically, the patient scored 0/5 on the Modified Ashworth Scale, ruling out clinically significant spasticity in the bilateral gastrocnemius or soleus muscles.17 As a result, botulinum toxin injections for treatment of spasticity were no longer indicated. Additionally, the side of the patient’s weakness did not correspond with the location of the stroke. Left basal ganglia strokes typically result in contralateral (right-sided) motor deficits. Coupled with the absence of spasticity, the assumption that these symptoms were caused by UMN lesions was challenged.

The left lateral disc herniation at the level of L4-5 could potentially explain the patient’s toe walking as a compensatory mechanism for L5 nerve root compression. L5 nerve root compression commonly results in foot drop, as the tibialis anterior acts to dorsiflex the foot. This patient may have unintentionally compensated for a left-sided foot drop by toe walking on the left side, ultimately causing a left-sided restriction in ankle pronation. However, the patient also reported radicular symptoms lateralized to the left leg, which may suggest a left lumbar radiculopathy. Further imaging, such as a lumbar MRI or repeat lumbar CT, may be indicated to reassess the disc herniation and further investigate nerve compression, disc degeneration, vertebral alignment, and other potential causes of LMN lesions.

Furthermore, the patient utilized a Lofstrand crutch on his right side, despite having left-sided weakness, adding another layer of complexity. This inconsistency may point toward compensatory mechanisms for balance, pain, or behavioral adaptation, but it does not fit well into the expected neuroanatomical patterns.

Given the discrepancy between imaging, clinical findings, and functional limitations, we reconsidered the etiology of toe walking. A key finding was the patient’s report of a shooting pain up the leg when attempting heel strike, which he avoided by walking on his toes. This pattern is inconsistent with spasticity-driven toe walking and instead suggests a LMN source, such as peripheral neuropathy (potentially diabetic) or a lumbar radiculopathy. An aircast was used for immediate relief,7 with a custom ankle-foot orthosis ordered for long-term gait stability and decreased pain.8 An EMG did not yield in-depth answers, but we are currently pursuing a diagnostic left tibial nerve block to further evaluate for possible tarsal tunnel syndrome.9 Cryoneurolysis may be the next treatment option, depending on the results.10

It is important to consider specific limitations to the assessment of this case. The patient’s stroke was an incidental finding on brain CT, which makes the timeline and presentation of the patient’s symptoms unclear. Additionally, the patient sees various physicians across different networks, which makes collaboration more difficult. The assessment and plan are limited to the currently available imaging, and specifically, a detailed EMG and MRI of the left foot are required to have a more accurate interpretation of this case. Additionally, the patient was taking paroxetine and may have benefited more from duloxetine due to his existing neuropathic pain and coexisting depression.

The patient was referred to outpatient physical therapy for a gait abnormality, with a planned frequency of 1–3 sessions per week over 6–12 weeks. These have intermittently given relief to the patient, but the patient continues to feel large amounts of pain and continues the compensatory toe walking. To the best of our knowledge, there are no articles documenting toe walking as a compensatory strategy for LMN dysfunction or peripheral neuropathy in adults. In a study of 174 children with toe walking, 17% (18/108) of those with a neurologic diagnosis had peripheral neuropathy.5 However, while that study shows coexistence, it does not necessarily show that toe walking was adopted as compensation for deficits from neuropathy.5 Our patient would likely benefit from the galantamine-memantine combination to treat his unique constellation of medical problems. Galantamine boosts cholinergic signaling and modulates nicotinic receptors, and memantine modulates NMDA/glutamatergic excitotoxicity.11 The galantamine-memantine combination can treat MDD,11 insomnia12,13 anxiety,14 and opioid use disorder.15 This patient is likely to have cognitive impairments (albeit, not measured) from stroke, MDD, and hypertension. The galantamine-memantine combination can treat cognitive impairments as well.11–14

Article Information

Published Online: January 22, 2026. https://doi.org/10.4088/PCC.25cr04111

© 2026 Physicians Postgraduate Press, Inc.

Prim Care Companion CNS Disord 2026;28(1):25cr04111

Submitted: October 15, 2025; accepted November 16, 2025.

To Cite: Riestra DB, Mitchell J, Riestra JM, et al. Unusual equinus gait in the absence of spasticity: a case of basal ganglia stroke with lower motor neuron features. Prim Care Companion CNS Disord 2026;28(1):25cr04111.

Author Affiliations: Rowan-Virtua School of Osteopathic Medicine, New Jersey (DB Riestra, Mitchell, Clements); Rutgers New Jersey Medical School, Newark, New Jersey (JM Riestra, Amonu); Cooper Medical School of Rowan University, Camden, New Jersey (Giunta); Department of Psychiatry and Behavioral Sciences, George Washington University School of Medicine and Health Sciences, Washington, DC (Koola).

Corresponding Author: Diana B. Riestra, BS, Rowan-Virtua School of Osteopathic Medicine, Sewell, NJ ([email protected]).

Financial Disclosure: None.

Funding/Support: None.

Acknowledgements: Tyler Pigott, DO (Department of Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation, Albert Einstein College of Medicine of Yeshiva University, Bronx, New York) was the attending pain management physician for this patient’s case. Ian Maitin, MD (Department of Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation, JFK Medical Center [HMH JFK University Medical Center], Edison, New Jersey) conducted the EMG nerve conduction study. Diana B. Riestra, BS, and Jessica Mitchell, MS, were the medical students assisting with the case. Kate Kerpen, MD (neurologist, Department of Neurology, Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai, New York, New York) provided valuable comments.

Patient Consent: Consent was received from the patient to publish the case report, and information, including dates, has been de-identified to protect patient anonymity.

References (16)

- Ruzbarsky JJ, Scher D, Dodwell E. Toe walking: causes, epidemiology, assessment, and treatment. Curr Opin Pediatr. 2016;28(1):40–46. PubMed CrossRef

- Kerrigan DC, Riley PO, Rogan S, et al. Compensatory advantages of toe walking. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2000;81(1):38–44. PubMed CrossRef

- Kuo AD, Donelan JM. Dynamic principles of gait and their clinical implications. Phys Ther. 2010;90(2):157–174. PubMed CrossRef

- Neptune RR, Burnfield JM, Mulroy SJ. The neuromuscular demands of toe walking: a forward dynamics simulation analysis. J Biomech. 2007;40(6): 1293–1300. PubMed CrossRef

- Haynes K, Wimberly R, VanPelt J, et al. Toe walking: a neurological perspective after referral from pediatric orthopaedic surgeons. J Pediatr Orthop. 2018;38(3): 152–156. PubMed CrossRef

- Mary P, Servais L, Vialle R. Neuromuscular diseases: diagnosis and management. Orthop Traumatol Surg Res. 2018;104(1S):S89–S95. PubMed CrossRef

- Günay S, Karaduman A, Oztürk BB. Effects of Aircast brace and elastic bandage on physical performance of athletes after ankle injuries. Acta Orthop Traumatol Turc. 2014;48(1):10–16. PubMed

- Gross MT, Mercer VS, Lin FC. Effects of foot orthoses on balance in older adults. J Orthop Sports Phys Ther. 2012;42(7):649–657. PubMed CrossRef

- Iborra Á, Villanueva M, Barrett SL, et al. The role of ultrasound-guided perineural injection of the tibial nerve with a sub-anesthetic dosage of lidocaine for the diagnosis of tarsal tunnel syndrome. Front Neurol. 2023;14:1135379. PubMed CrossRef

- Barker AR, Rosson GD, Dellon AL. Outcome of neurolysis for failed tarsal tunnel surgery. J Reconstr Microsurg. 2008;24(2):111–118. PubMed CrossRef

- Koola MM. Galantamine-Memantine combination for cognitive impairments due to electroconvulsive therapy, traumatic brain injury, and neurologic and psychiatric disorders: kynurenic acid and mismatch negativity target engagement. Prim Care Companion CNS Disord. 2018;20(2):17nr02235. PubMed CrossRef

- Naharci MI, Ozturk A, Yasar H, et al. Galantamine improves sleep quality in patients with dementia. Acta Neurol Belg. 2015;115(4):563–568. PubMed CrossRef

- Ishikawa I, Shinno H, Ando N, et al. The effect of memantine on sleep architecture and psychiatric symptoms in patients with Alzheimer’s disease. Acta Neuropsychiatr. 2016;28(3):157–164. PubMed CrossRef

- Bai MY, Lovejoy DB, Guillemin GJ, et al. Galantamine-Memantine combination and kynurenine pathway enzyme inhibitors in the treatment of neuropsychiatric disorders. Complex Psychiatry. 2021;7(1-2):19–33. PubMed CrossRef

- Elias AM, Pepin MJ, Brown JN. Adjunctive memantine for opioid use disorder treatment: a systematic review. J Subst Abuse Treat. 2019;107:38–43. PubMed CrossRef

- Harb A, Margetis K, Kishner S. Modified Ashworth Scale. StatPearls. StatPearls Publishing; 2025.

Enjoy this premium PDF as part of your membership benefits!