Lessons Learned at the Interface of Medicine and Psychiatry

The Psychiatric Consultation Service at Massachusetts General Hospital sees medical and surgical inpatients with comorbid psychiatric symptoms and conditions. During their twice-weekly rounds, Dr Stern and other members of the Consultation Service discuss diagnosis and management of hospitalized patients with complex medical or surgical problems who also demonstrate psychiatric symptoms or conditions. These discussions have given rise to rounds reports that will prove useful for clinicians practicing at the interface of medicine and psychiatry.

Prim Care Companion CNS Disord 2025;27(6):25f03994

Author affiliations are listed at the end of this article.

Have you ever wondered why, and whether, you should attempt to be promoted? Have you been uncertain about what it takes or felt that you lacked the skill set necessary to achieve academic promotions? Have you wondered how, given your clinical workload, you could find the time to prepare written scholarship? If you have, the following case vignette and discussion should prove useful.

CASE VIGNETTE

Dr A, a 32-year-old primary care physician, had been practicing full-time in an academic-affiliated community clinic for 5 years. After completing residency, he remained within the same health system due to the supportive environment and proximity to family. Although his primary role was clinical, he had always enjoyed teaching residents and medical students who rotated through the clinic.

One afternoon, during a casual conversation with a colleague, Dr A learned that several of his peers had recently been promoted to assistant professor. He was surprised, as he had not even realized they were on a promotion track, and he began to wonder: “Am I missing out on opportunities? Would pursuing academic advancement open more doors for me?”

Initially, his interest in promotion was driven by curiosity and a desire for recognition. He also saw potential benefits (eg, invitations to speak, chances to engage in leadership on a regional level, and a more competitive curriculum vitae [CV] that could enhance his long-term job stability). However, as he reflected more deeply, Dr A realized that he was motivated by a sincere desire to make a broader impact, especially in medical education and possibly in advancing health equity.

He decided to reach out to his division chief, who encouraged him to attend a faculty development seminar hosted by the institution’s office of faculty affairs. There, Dr A learned about the criteria for academic promotion (involving clinical excellence, contributions to teaching, scholarship, and service to the profession). The session highlighted the importance of creating a comprehensive promotion portfolio with documentation of lectures, mentorship, publications, and committee work.

Dr A was energized but soon encountered several barriers. His clinic schedule was packed and carving out time for scholarly writing or attending conferences seemed nearly impossible. In addition, the promotion guidelines seemed vague, and he was not sure what “counts” or how much was “enough.” At times, he doubted whether he was suited for academic advancement, and he struggled with feelings that he was an imposter.

DISCUSSION

Why Might a Practicing Clinician Seek Academic Advancement?

Practicing clinicians seek academic advancement for a range of personal, professional, and institutional reasons that extend well beyond ego gratification or financial incentives. A career in academic medicine offers the opportunity to foster intellectual curiosity and pursue meaningful contributions to the field, which often leads to long-term career satisfaction. Academic advancement also provides a strong sense of connection, community, and teamwork, helping clinicians feel more engaged and valued within their institutions.1

Promotion is widely considered a key metric of academic success. For many medical faculty members, promotion is not only an expected career milestone but also a requirement. Advancing in academic rank is often accompanied by substantial benefits, including increased financial compensation, access to leadership and grant funding opportunities, and enhanced recognition within and outside of the institution. The enhanced reputation associated with academic promotion frequently translates into increased social capital, opening the door to leadership positions in national organizations and allowing for greater contributions to the field at large.2

Academic promotions also carry symbolic weight. Promotions reflect an individual’s scholarly accomplishments and their “value” to the discipline. Academic advancement may also be valuable in industries outside of hospital settings, such as in the media or start-ups, as many medical consultants often have extensive academic credentials. Conversely, failure to attain promotion within anticipated timeframes can be perceived as a lack of productivity or impact.3 In some academic settings, promotion conveys job security, which allows for greater academic freedom and the ability to undertake long-term projects that might not be feasible in other roles.

From a practical standpoint, academic advancement often comes with increased flexibility and protected time for teaching and research. This balance can improve work satisfaction and sustainability by reducing the burden of clinical duties and providing space for creative and scholarly pursuits. Promotion can also expand the impact of a clinician’s research through increased visibility and opportunities for dissemination of information, potentially benefiting more patients and influencing clinical practice. Moreover, having a higher academic rank often comes with more opportunities to mentor and train the next generation of physicians.

Beyond individual benefits, academic advancement contributes to a culture of excellence within departments and institutions. Promotions typically enhance one’s institutional prestige, attract competitive applicants, and build patient trust in the care provided by academically distinguished clinicians.4 In this way, pursuing academic promotion supports the clinician’s career and the overall mission and reputation of the academic medical center.

What Are Some Commonly Perceived Barriers for Clinicians Seeking Academic Promotion?

Clinicians often perceive barriers that can discourage them from pursuing academic promotion, even though they are highly qualified. These barriers often stem from the demands of clinical work and the complexities of the academic system. One of the most frequently cited challenges is a lack of time. Clinicians often have heavy clinical loads, administrative responsibilities, and personal commitments, which can make it difficult to carve out time for scholarly activities (eg, research, writing, teaching, or attending development programs that are key components of academic advancement).5–7 Other significant challenges include having limited access to mentorship and guidance. Effective mentorship plays a vital role in achieving academic success, yet many clinicians report that their mentorship is inadequate, in part due to difficulty finding mentors who can provide targeted scientific guidance and sustained, long-term support.7 Without experienced mentors to help navigate the promotion process, clinicians often feel uncertain about what is required, which activities carry the most academic value, or how to document their accomplishments. Moreover, mentorship may not necessarily lead to sponsorship, eg, being nominated for awards, invited to collaborate on papers/projects, or being suggested for committees or leadership positions. Lack of mentorship, or mentorship without sponsorship, can lead to missed opportunities for advancement or to delays in preparing promotion materials.

In addition, some clinicians become puzzled by promotion criteria. Academic promotion requirements often vary widely among institutions and departments, and the expectations for candidates may not always be clearly communicated, leaving clinicians feeling unsure about what is expected or how their work will be evaluated.8,9 For example, while some institutions prioritize research output and publications for promotion, others place more emphasis on teaching excellence, clinical innovation, or leadership in administrative roles. Such ambiguity in promotion guidelines leads to frustration, particularly for those in nontraditional academic tracks (eg, clinician-educator or clinician-administrator), where scholarly contributions may look different than traditional research output.

Experiencing the “imposter syndrome” and a lack of confidence also serve as barriers. For many clinicians, particularly those early in their academic careers, imposter syndrome can foster the false belief that they are unqualified for promotion, even when their accomplishments meet or exceed the criteria set by their institution. They may feel as if they have not done “enough” to be promoted, despite having a solid history of clinical excellence, teaching, or research contributions. This is especially common among women and underrepresented groups in academic medicine.10

Moreover, institutional culture or a lack of support may further discourage promotion efforts. If the environment does not actively encourage or reward academic achievement, clinicians may not feel motivated or empowered to pursue promotion. Without institutional recognition, protected time, or incentives, the path to academic advancement can feel especially challenging and burdensome. In addition, discrimination and unequal distribution of care duties may disproportionately affect minoritized groups.11,12

Finally, burnout has increasingly become a challenge, which has not only diminished interest in academic medicine but also contributed to people leaving the field of academic medicine.13 As academic advancement involves many competing needs and interests, this could potentially elicit an emotional depletion, which may further diminish motivation.

How Do Personal Identity and Background Influence a Clinician’s Expectations for, and Decisions About, Academic Promotion?

Academic promotion is a multifaceted process aimed at demonstrating academic competence, and it is shaped not only by institutional expectations but also by the personal identity and background of the clinician. Professional identity represents an intersection of personal values and the values of the profession,14 and this interplay can significantly influence how clinicians approach and experience the promotion process.

A clinician’s social identity, which includes factors such as gender, race, ethnicity, and socioeconomic background, can shape their sense of belonging within an academic institution. This, in turn, may affect how they perceive the fairness, accessibility, and relevance of the promotion process, as well as their motivation to pursue advancement.

For faculty from groups underrepresented in medicine, navigating the promotion process can be particularly challenging due to limited access to mentorship, especially from mentors who share aspects of their identity.15 The lack of identity-concordant mentorship can make it harder to receive tailored guidance and advocacy. Moreover, research has shown that women have historically experienced slower promotion trajectories,16 which can contribute to lower expectations for advancement and increased discouragement.

Personal values related to self-promotion, collaboration, and hierarchy also play a critical role. For example, some clinicians are less comfortable with self-promotion and may instead prioritize collaborative achievements. These clinicians may be hesitant to nominate themselves for recognition but may be much more comfortable working on projects as part of a team. In some cultural contexts, collective success is emphasized over individual recognition,17 potentially influencing how a clinician presents their accomplishments and engages with the promotion process. Not everyone needs to receive accolades, titles, and promotions to bolster their sense of self, or to increase their salary, or to receive a larger office. However, many such clinicians will proceed along with the promotion gauntlet for the benefit of others to show that promotions are possible and can facilitate the growth and development of others.

A clinician’s background and experiences also affect their comfort with engaging promotion committees, whether in advocating for themselves, interpreting feedback, or navigating institutional hierarchies. While some individuals feel confident in articulating their accomplishments, others are hesitant due to their experiences or internalized expectations.

Ultimately, one’s academic identity is a personal narrative shaped over time by experience, values, and beliefs. Understanding how identity influences this narrative is essential for institutions seeking to foster fair, supportive, and representative pathways to academic promotion.

What Does It Take to Be Promoted at Academic Institutions?

The expectations for practitioners of primary care and family medicine differ from those of psychiatry. Most primary care and family medicine providers are hired to provide care to large panels of patients, not to innovate or publish scholarly works. Therefore, in many medical centers, the currency of the realm is providing high-volume clinical care (and associated referrals and revenue) rather than research findings or publications (which is a contributor to high rates of turnover of health care providers). Promotion, in many of the centers, rewards clinical care and is automatic after a certain number of years pass. Ongoing opportunities for continuing education are frequently not supported financially by clinical departments, which minimizes the incentives to attend postgraduate educational conferences where faculty can be stimulated by the thinking of others from across the country.

Information sessions about appointments, reappointments, promotions, and academic titles frequently get short shrift (and frequently go unattended) in departments that value clinical care. Nevertheless, it is wise for junior faculty to know what is expected of them now and in the future and to realize that the criteria differ from one hospital to another. Academic medical systems generally recognize scholarly activities (eg, the creation and dissemination of new knowledge) in the areas of (1) patient care, (2) teaching, (3) investigation, and (4) engagement.18,19

Patient Care

The clinician-scholar benefits from bringing both clinical excellence and an academic mindset to patient care. Academic physicians stay abreast of advances in the literature related to their patients (eg, deriving knowledge from articles identified in PubMed and in textbooks) and practice evidence-based and patient-centered clinical care. They attend to the fundamentals of current medical practices and stay mindful of research concepts, employ excellent judgment, demonstrate humility, and remain open-minded when teaching and learning from colleagues and their patients. Recognition from their peers and patients as excellent clinicians and consultants, demonstration of written scholarship, practicing evidence-based medicine, providing high-quality clinical care, and contributing to the profession and their home institution help to cement the identity of clinician-educators. Academic clinicians often develop and maintain programs that enhance patient outcomes and access to care.

Evidence of one’s impact as a clinician-scholar can be gleaned from a variety of activities such as leading, organizing, or participating as a faculty member in local, regional, or national venues that spread high-quality medical knowledge (eg, departmental grand rounds, local or state medical society meetings, or continuing medical education courses). Leadership roles in local or regional clinical affairs (eg, serving as a section chief, clerkship director, departmental vice chair, departmental chair, center director, or service line director) and active and ongoing participation in committees, programs, and governing boards also demonstrate one’s influence as a clinician-scholar. Fellowship in specialty academies also reflects one’s stature in the field, bestowed by peers related to one’s abilities, talents, and contributions to the profession.

Teaching and Research

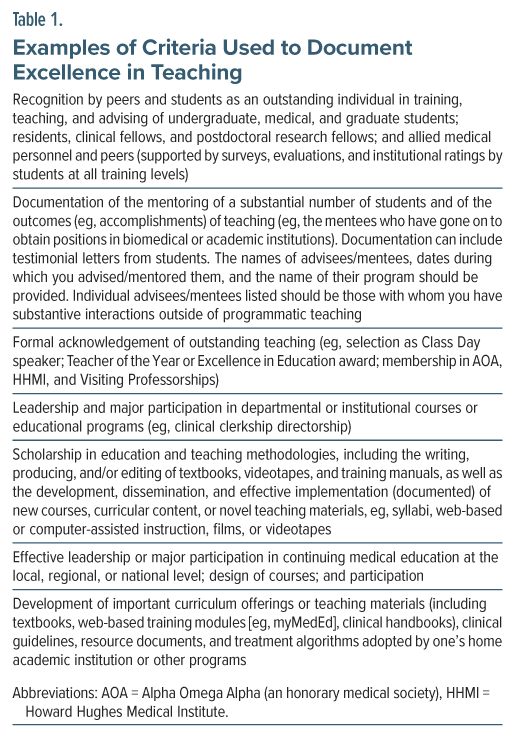

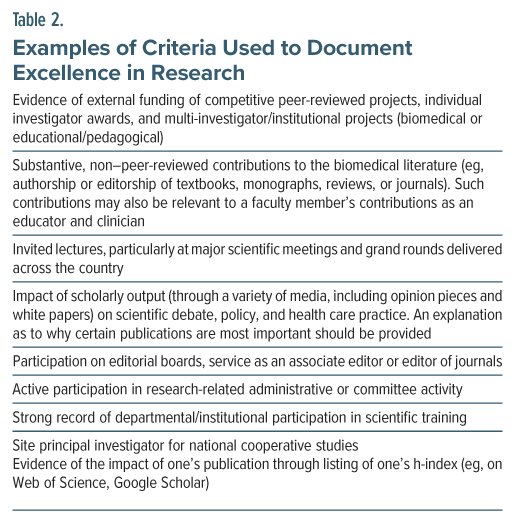

The goal of scholarship is to educate trainees and lifelong learners inside and outside of one’s academic home. A clinician-scholar’s contribution to teaching and its impact on learners can be documented by demonstrating participation in didactic courses and training of trainees (eg, mentees and through service on educational committees). Table 1 provides a list of examples of criteria often used to document excellence in teaching. Table 2 provides examples of criteria for excellence in research.

Engagement

Engagement is one of the key goals of scholarship: It extends academic efforts beyond one’s clinical, research, or didactic responsibilities to have a broader impact on the biomedical community (within the home institution and upon the greater society). Although committee membership is recognized as a valuable contribution to the academic community and is considered in the evaluation for appointment or promotion, engagement goes beyond service.

Engagement can include the following: (1) appointment or election to membership/leadership roles and active participation in major societies, committees/ programs, national professional organizations, and governing boards and organizations for major professional meetings and (2) membership or leadership on editorial boards, study sections, and advisory groups. Clinician-scholars who say “yes” frequently to collaborations and participation in projects are rewarded for their involvement and for their community-building professional engagement (eg, inviting copresenters from multiple academic sites for presentations and papers, specialty interest group leadership, and participation).

What Should the Personal Statement of a Clinician-Educator Applying for Academic Promotion Include?

The personal statement of a clinician-educator who seeks to be promoted should include documentation of clinical excellence and expertise, as well as demonstration of the impact of their educational activities and the peer recognition associated with those activities. This task is somewhat easier for investigators because they can list large grants and peer-reviewed papers as evidence of recognition; however, for clinicians, demonstration of their impact may require more creativity. Writing a personal statement or narrative is an art, not a science. Everyone’s path is different; therefore, the goal is to create your own story. It is often valuable to confer with others in your subspecialty (as some specialties are clinical and ideographic, eg, consultation-liaison psychiatry) about how they approached this task and then see how you can learn from what they have described. It is best to avoid the use of acronyms or jargon. The personal statement is about how you brought your unique brand to the role of clinician-scholar. Remember, you are telling a story—“this is who I am,” “this is what I care about,” and “this is how I have made an enduring impact.”

The personal statement should also focus on one’s regional and national impact, rather than on just “what you do.” This statement can help to explain the details of your CV, but it should also detail what you have accomplished. For example, a narrated presentation on “catatonia” featured online that teaches trainees about the neuropsychiatry and standardized examination and treatment of catatonia should mention what happened because of, or what will happen because of, a specific project (eg, adoption by other academic institutions, number of downloads or page views). It is often helpful to pretend that you are nominating someone for an award, and your goal is to make a case for how that person made a difference.

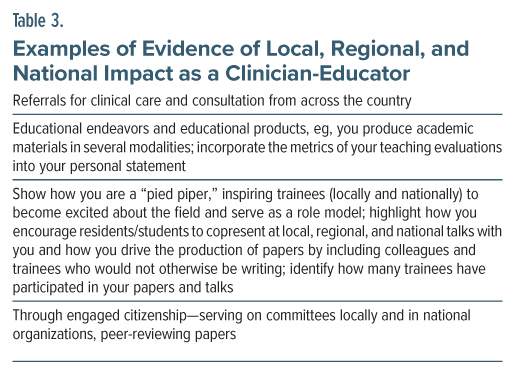

It also helps to focus on what an applicant for promotion is passionate about, for example, (1) patient care, (2) direct clinical teaching and local mentoring, (3) indirect clinical teaching through the development of educational materials and national recognition for teaching, (4) engagement of students and trainees in thinking and developing academically, and (5) expertise in a specific topic and national recognition for teaching about that topic. Table 3 provides examples of local, regional, and national impact as a clinician-educator.

How Can One Learn the Skills Required for Academic Success/Promotion?

At many academic institutions, promotions often proceed along several paths, areas of excellence, or tracks (eg, investigation, clinical expertise and innovation, and teaching and educational leadership).20 However, few practicing clinicians devote enough time for research projects (eg, learning how to write grants, obtaining funding, and publishing results of original research) to clear the bar for promotion with an area of excellence of investigation. Instead, many clinicians invest a significant portion of their time in teaching (eg, supervising in a clinic or at the bedside, delivering didactics on their area of expertise), administering training programs, and mentoring the next generation of clinician-teachers.21 Achieving excellence in teaching requires knowledge about content (eg, pathophysiology, epidemiology, laboratory test results, and treatment alternatives for symptoms and conditions) and process (eg, understanding and applying principles of adult learning theory, appreciating how learners learn best, and facilitating change) while being engaging, empathic, supportive, and respectful.

Given the disparate learning styles of trainees (eg, hearing talks or podcasts, viewing interactions or videos, performing procedures), clinician-teachers need to be flexible in their approach. Skill building can be facilitated by enrollment in courses on interviewing, conducting a physical examination, refining teaching techniques, presenting effective PowerPoint lectures, delivering feedback, and integrating artificial intelligence into clinical documentation, just to name a few options. Although all clinicians devote countless hours to documentation in the medical record, few physicians learn how to translate what they see and do into scholarly publications.22 As with other activities associated with clinical work, scholarly writing is a skill that must be honed; unfortunately, writing seminars for clinicians are rarely offered.23 When such seminars are conducted, they can guide attendees to identify the patient problems and encounters that provide the opportunity to teach others, often addressing who, what, where, why, and how questions for the appropriate target audience (ie, making it relevant to the reader and learner). Writing groups can refine the questions asked, facilitate the organization of the manuscript, provide the deadlines and structure for the response to the queries, and guide the editing process. Moreover, they can help to identify which journal would provide the best home for the article, how to prepare the manuscript to match the criteria for each type of article (eg, case report, case series, review article, case conference), and how to communicate with the journal’s editorial staff (for submissions and for requested revisions). In addition, clinician-teachers can refine their skills for public speaking to enhance effective communication. Guidance can be offered on the volume, pace, eye contact, and interactivity of the speaker as well as how to format and discuss material on slides to facilitate readability, clarity of thought, and engagement with the material and the speaker.

Every hospital with academic aspirations should offer seminars, coaches, and mentors regarding the skills necessary for academic success (eg, scholarly writing/ publications, public speaking/lecturing, teaching/ mentorship). One of the most effective ways of developing these skills is to pair a junior person with a more senior mentor who can “ride shotgun” and guide the project or activity with real-time feedback that shapes the performance step by step, making each phase manageable (ie, with short time spans [such as less than 10 hours of work] and tasks [such as less than 3 double-spaced pages of text] and willing collaborators, as this makes editing easier and less onerous). Furthermore, novel solutions that can help clinicians alleviate the administrative burden associated with advancement could be highly valuable resources.24

Where Can a Clinician Find Mentors to Facilitate Their Academic Success?

Even with an understanding of the elements that might be necessary for promotion, it still may be difficult to document a portfolio worthy of promotion. Further, the process may be difficult to navigate. Having mentors who have navigated this process and are also willing to act as enthusiastic sponsors can help physicians embark on an academic career and approach the promotion gauntlet.

Beyond its utility in seeking promotion, mentorship has other benefits25 (eg, enhancing research productivity, being prepared for faculty roles,26 and enjoying increased career satisfaction).27 However, it is often difficult for physicians to know how to access and establish mentor-mentee relationships. For physicians who work in academic teaching hospitals, mentorship can be accessed through one’s university or medical school. For instance, many universities have an office that assists with professional development and that can facilitate the identification of, and contact with, willing mentors. A teaching hospital’s clinical department or residency training program can also connect mentors to mentees, especially with a mentor who shares similar clinical and academic interests.

For those who do not work in academic teaching hospitals, or for those who prefer to connect with mentors from different institutions, national organizations (eg, the American Psychiatric Association) or subspecialty organizations (eg, the Academy of Consultation-Liaison Psychiatry) often offer mentorship resources. Physicians can also connect with mentorship that is tailored toward affinity groups (eg, underrepresented in medicine25 or women in medicine28).

How Can One Find the Time Required to Produce Written Scholarship and Oversee the Submission/Publication Process?

A lack of written scholarship represents a common barrier for those seeking academic promotion.29 While it is important for academic medical centers to reinforce their dedication to the academic mission by strengthening support, resources, and structures which enhance a culture of generativity, it is still incumbent upon those seeking academic promotion to participate in scholarship. Often cited as the cause for a lack of scholarship is a lack of time or bandwidth for such activities.30 Academic physicians often have challenging jobs that involve balancing many duties (eg, patient care, trainee teaching, or administrative duties) that leave little time for academic productivity. As such, physicians seeking promotion must employ strategic solutions that fit academic projects into their busy schedules.

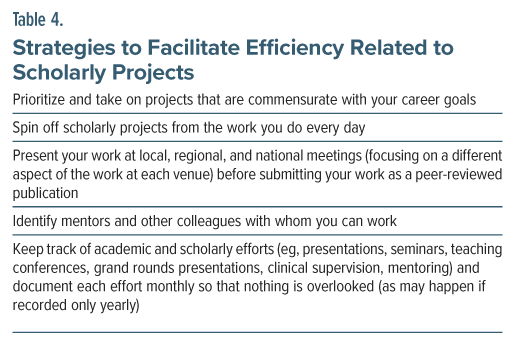

Although the details of time management may be beyond the scope of this paper, it is important to set aside time for scholarly projects (Table 4). Being efficient helps to make the most out of the time allotted to projects. With time and bandwidth in short supply for academic physicians, projects should be selected wisely. When one’s career goals are aligned with scholarly projects (declining projects that are misaligned), productivity will be enhanced, maximizing the use of precious time and bandwidth.31

As academic physicians frequently fill multiple roles, educational and scholarly opportunities can be triggered by work that is already being accomplished each day30–32 (eg, elaborating on interesting clinical cases or quality improvement initiatives). Schrager and Sadowski proposed making “every effort count twice or thrice” as another strategy,31 with academic projects involving a presentation at a local or regional meeting, then at a national meeting (if allowable by the meeting guidelines), and then transformed into a peer-reviewed publication. Deriving multiple presentations or papers from a single project (each geared toward a different clinical audience with a different focus) can be a time-efficient way to generate written scholarship. Finally, working with mentors and colleagues who employ a “divide and conquer” work philosophy increases efficiency, reduces the workload, and provides mutual support.30

Learning strategies to turn clinical experience into scholarly publications can help clinicians become more efficient, more productive, and more widely recognized for their clinical expertise. One strategy to supplement this approach is to collaborate with trusted colleagues and to use a “divide and conquer approach” that relies on teamwork and shared goals.

What Happened to Dr A?

Dr A sought mentorship through his residency program alumni network and found a mentor who had recently been promoted. She helped him map out a realistic timeline and introduced him to writing workshops and speaking seminars. She also encouraged him to strategically pursue and accept the opportunities that aligned with his interests, such as giving virtual talks on preventive care in marginalized communities and co-authoring a short commentary on culturally competent care.

He also realized the importance of visibility and reputation—not just within his clinic but regionally and nationally. He joined a working group within a national primary care organization and began reviewing abstracts for their annual conference. Slowly, he built a scholarly footprint.

For Dr A, the journey was shaped not just by ambition but by mentorship, identity, and community. As a first-generation physician and a person of color, he found navigating academic norms challenging—particularly around self-promotion, which felt at odds with his upbringing. But with support, he redefined academic success on his own terms: contributing to his field while staying grounded in the values that brought him into medicine in the first place.

When the time came, his division chief and department chair submitted his name for promotion. His file was reviewed by the faculty promotion committee and forwarded to the dean’s office for final approval. A few months later, Dr A was promoted to the rank of assistant professor.

CONCLUSION

Academic advancement relies on different criteria at hospitals and medical schools across the nation. Unearthing the process and the criteria for promotion as a clinical expert and innovator is crucial to engaging in their process, as longevity in a system is not always sufficient to qualify for promotion. Frequently, promotion revolves around building a local, regional, or national reputation (earned by speaking engagements, academic writing, involvement in professional societies, and more).

Clinicians often perceive barriers (eg, lack of time due to heavy clinical loads, administrative responsibilities, and personal commitments) that can discourage them from pursuing academic promotion, even though they are highly qualified and that can make it difficult for them to become involved in scholarly activities (eg, research, writing, teaching, or attending development programs) that are key components of academic advancement. Further, inadequate mentorship can contribute to missed opportunities for advancement or to delays in preparing promotion materials. Without institutional support (eg, protected time, incentives), the path to academic advancement can feel daunting.

Scholarly writing is a skill that must be honed; unfortunately, writing seminars for clinicians are rarely offered. However, such seminars can guide clinicians to identify the patient problems and encounters that provide them with the opportunity to teach others, often addressing who, what, where, why, and how questions that are relevant for the target audience. When one’s career goals are aligned with scholarly projects, productivity will be enhanced, maximizing use of precious time and bandwidth.

Article Information

Published Online: December 16, 2025. https://doi.org/10.4088/PCC.25f03994

© 2025 Physicians Postgraduate Press, Inc.

Submitted: May 2, 2025; accepted August 13, 2025.

To Cite: Rustad JK, Ho PA, Herrera Santos LJ, et al. Facilitating academic success for practicing clinicians. Prim Care Companion CNS Disord 2025;27(6):25f03994.

Author Affiliations: Geisel School of Medicine at Dartmouth, Lebanon, New Hampshire (Rustad, Ho); Larner College of Medicine at University of Vermont, Burlington, Vermont (Rustad); White River Junction VA Medical Center, White River Junction, Vermont (Rustad); Burlington Lakeside Community Based Outpatient Clinic, Burlington, Vermont (Rustad); Dartmouth-Hitchcock Medical Center, Lebanon, New Hampshire (Ho); Brigham and Women’s Faulkner Hospital/Harvard Medical School, Boston, Massachusetts (Lee); Massachusetts General Hospital/Harvard Medical School, Boston, Massachusetts (Stern, Herrera Santos).

Corresponding Author: James K. Rustad, MD, Department of Psychiatry, Geisel School of Medicine at Dartmouth, Dartmouth-Hitchcock Medical Center, One Medical Center Dr, Lebanon, NH 03756 ([email protected]).

Rustad, Ho, Herrera Santos, and Lee are co-first authors; Stern is the senior author.

Relevant Financial Relationships: Dr Rustad is employed by the US Department of Veterans Affairs, but the opinions expressed in this article do not reflect those of the Department of Veterans Affairs. Dr Stern has received royalties from Elsevier for editing textbooks on psychiatry.

Funding/Support: None.

Acknowledgements: Dr Rustad would like to thank Will Torrey, MD; Paula Schnurr, PhD; and Brian Shiner, MD/MPH for their invaluable guidance throughout the promotional process.

Additional Information: This article is largely directed at junior faculty (instructors and assistant professors). The authors hope to guide them through the process and criteria for academic advancement.

Clinical Points

- Many clinicians, particularly those early in their careers, experience the “imposter syndrome” that can foster the false belief that they are unqualified for promotion, even when their accomplishments meet or exceed the criteria set by their institution.

- Evidence of one’s impact as a clinician-scholar can be gleaned from a myriad of educational activities (eg, leading, organizing, or participating as a faculty member in local, regional, or national venues that spread high-quality medical knowledge), leadership roles (eg, serving as a section chief, clerkship director, center director), and active and ongoing participation in committees.

- The personal statement of a clinician-educator should demonstrate the impact of their educational activities and the peer recognition associated with those activities.

- Every hospital with academic aspirations should offer seminars, coaches, and mentors regarding the skills necessary for academic success (eg, scholarly writing/ publications, public speaking/lecturing, and teaching/ mentorship).

- Working with mentors and colleagues who employ a “divide and conquer” work philosophy increases efficiency, reduces the workload, and provides mutual support.

References (32)

- Howard-Anderson JR, Gewin L, Rockey DC, et al. Strategies for developing a successful career in academic medicine. Am J Med Sci. 2024;367(4):215–227. PubMed CrossRef

- Chapman T, Maxfield CM, Iyer RS. Promotion in academic radiology: context and considerations. Pediatr Radiol. 2023;53(1):8–11. PubMed CrossRef

- Todisco A, Souza RF, Gores GJ. Trains, tracks, and promotion in an academic medical center. Gastroenterology. 2011;141(5):1545–1548. PubMed CrossRef

- Alam H. Promotion. Clin Colon Rectal Surg. 2013;26(4):232–238. PubMed CrossRef

- Zmijewski P, Obiarinze R, Gillis A, et al. Determinants and barriers to junior faculty well-being at a large quaternary academic medical center: a qualitative survey. Surgery. 2022;172(6):1744–1747. PubMed CrossRef

- Yoon S, Koh WP, Ong MEH, et al. Factors influencing career progress for early stage clinician-scientists in emerging Asian academic medical centres:a qualitative study in Singapore. BMJ Open. 2018;8(3):e020398. PubMed CrossRef

- Lin CY, Greco C, Radhakrishnan H, et al. Experiences of the clinical academic pathway: a qualitative study in Greater Manchester to improve the opportunities of minoritised clinical academics. BMJ Open. 2024;14(3):e079759. PubMed CrossRef

- Schimanski LA, Alperin JP. The evaluation of scholarship in academic promotion and tenure processes: past, present, and future. F1000Res. 2018;7:1605. PubMed CrossRef

- Chang A, Karani R, Dhaliwal G. Mission critical: reimagining promotion for clinician-educators. J Gen Intern Med. 2023;38(3):789–792. PubMed CrossRef

- Vaa Stelling BE, Andersen CA, Suarez DA, et al. Fitting in while standing out: professional identity formation, imposter syndrome, and burnout in early-career faculty physicians. Acad Med. 2023;98(4):514–520. PubMed CrossRef

- Vassie C, Smith S, Leedham-Green K. Factors impacting on retention, success and equitable participation in clinical academic careers: a scoping review and meta-thematic synthesis. BMJ Open. 2020;10(3):e033480. PubMed CrossRef

- Bateman LB, Heider L, Vickers SM, et al. Barriers to advancement in academic medicine: the perception gap between majority men and other faculty. J Gen Intern Med. 2021;36(7):1937–1943. PubMed CrossRef

- Bannerjee G, Mitchell JD, Brzezinski M, et al. Burnout in academic physicians. Perm J. 2023;27(2):142–149. PubMed

- Chow CJ, Byington CL, Olson LM, et al. A conceptual model for understanding academic physicians’ performances of identity: findings from the University of Utah. Acad Med. 2018;93(10):1539–1549. PubMed CrossRef

- Espino MM, Zambrana RE. “How do you advance here? How do you survive?” An exploration of under-represented minority faculty perceptions of mentoring modalities. Rev Higher Education. 2019;42(2):457–484. CrossRef

- Marcotte LM, Arora VM, Ganguli I. Toward gender equity in academic promotions. JAMA Intern Med. 2021;181(9):1155–1156. PubMed CrossRef

- Gelfand MJ, Erez M, Aycan Z. Cross-cultural organizational behavior. Annu Rev Psychol. 2007;58(1):479–514. PubMed CrossRef

- Academic Appointments. Promotions and Titles at Geisel School of Medicine at Dartmouth. Accessed April 17, 2025. https://geiselmed.dartmouth.edu/faculty/pdf/Promotions%20Guide%20Tenure.Tenure-track%20Line%20Faculty.pdf

- Appendix 5. Guidelines for Faculty Promotion Procedures: Tenure-track/Tenure, Non-tenure, and AMS Faculty Lines. Accessed April 17, 2025. https://geiselmed.dartmouth.edu/ofa/document/appointments-promotions-titles/appendix-5-guidelines-for-faculty-promotion-procedures/

- Gerken AT, Beckmann DL, Stern TA. Fostering careers in medical education. Psychiatr Clin North Am. 2021;44(2):283–294. PubMed CrossRef

- Amonoo HL, Barreto EA, Stern TA, et al. Residents’ experiences with mentorship in academic medicine. Acad Psychiatry. 2019;43(1):71–75. PubMed CrossRef

- Cromwell JC, Daunis DJ, Stern TA. Turning oral presentations at the Academy of Consultation-Liaison Psychiatry/s annual meeting into published articles: a review and analysis. Psychosomatics. 2020;61(1):19–23. PubMed CrossRef

- Stern TA, Beach SR, Smith FA, et al. Preface. In: Stern TA, Beach SR, Smith FA, et al, eds. Massachusetts General Hospital Handbook of General Hospital Psychiatry. 8th ed. Elsevier; 2025. xxv-xxxii.

- Nadkarni A, Bhattacharyya S, Becker M, et al. A pilot of academic coordination improves faculty burnout and enhances support for the academic mission. Acad Psychiatry. 2025;49(2):202–203. PubMed CrossRef

- Bonifacino E, Ufomata EO, Farkas AH, et al. Mentorship of underrepresented physicians and trainees in academic medicine: a systematic review. J Gen Intern Med. 2021;36(4):1023–1034. PubMed CrossRef

- Palepu A, Friedman RH, Barnett RC, et al. Junior faculty members’ mentoring relationships and their professional development in U.S. medical schools. Acad Med. 1998;73(3):318–323. PubMed CrossRef

- DeCastro R, Griffith KA, Ubel PA, et al. Mentoring and the career satisfaction of male and female academic medical faculty. Acad Med. 2014;89(2):301–311. PubMed CrossRef

- Farkas AH, Bonifacino E, Turner R, et al. Mentorship of women in academic medicine: a systematic review. J Gen Intern Med. 2019;34(7):1322–1329. PubMed CrossRef

- Sumarsono A, Keshvani N, Saleh SN, et al. Scholarly productivity and rank in academic hospital medicine. J Hosp Med. 2021. PubMed CrossRef

- Jha P, Bhandari S, Slawski B. Strategies to promote scholarship among academic hospitalists. Br J Hosp Med. 2024;85(7):1–3. PubMed CrossRef

- Schrager S, Sadowski E. Getting more done: strategies to increase scholarly productivity. J Grad Med Educ. 2016;8(1):10–13. PubMed CrossRef

- Lin D. Leadership and professional development: cultivating a path for hospitalist educators to achieve scholarly success. J Hosp Med. 2024;19(2):126–127. PubMed CrossRef

Enjoy this premium PDF as part of your membership benefits!