Abstract

Objective: To explore the effect of a patient’s suicide on mental health professionals (MHPs), the perceived psychological and professional impacts, the support MHPs require versus actually receive, and their views on training that is provided to cope with such incidents.

Methods: A mixed-methods approach was used. An online survey was conducted from September to October 2023. The validated semistructured questionnaire was open for 8 weeks and covered demographics, details of incidents, emotional and professional impacts, and support systems. Responses were analyzed using descriptive statistics and thematic analysis to derive insights from qualitative data.

Results: Among 96 responses, 51% had treated patients who died by suicide. These patients were mostly males, primarily diagnosed with psychotic or affective disorders. Of the MHP respondents, 76.6% experienced suicide of a patient after completing their training. Around one-third reported moderate-to-extreme emotional impact of the incident, with sadness, regret, and guilt being common responses. Support-seeking behaviors were common with 52.2% of respondents finding support from colleagues, family, or professional communities helpful, but formal training on managing patient suicide was found to be lacking.

Conclusion: Patient suicide can impact MHPs, affecting emotional well-being, professional identity, and personal life, emphasizing the importance of establishing a supportive environment, incorporating enhanced training into psychiatry programs, and encouraging open dialog.

Prim Care Companion CNS Disord 2025;27(6):25m03995

Author affiliations are listed at the end of this article.

Suicide is a prominent global health and social issue, with an estimated 800,000 people dying due to suicide annually. For every suicide, approximately 6–20 people (usually family members and acquaintances) are adversely affected.1,2

For mental health professionals (MHPs), the tragedy of a patient’s suicide is likely to be experienced at some point in their careers, evoking intense emotional distress comparable to that of a family member.3–5 MHPs have higher exposure to suicide than the general public, including the bereaved family members and friends, primarily due to the nature of their work, which often involves forming close therapeutic alliances with individuals who may be at high risk of suicide.6,7 Despite their pivotal role, the impact of patient suicide exposure on MHPs remains an underexplored area.

These incidents may trigger a range of emotional and behavioral responses such as sadness, shock, guilt, fear, persistent low mood, distress, and diminished self-confidence, often accompanied by feelings of professional inadequacy. Some clinicians report fear of litigation and consider leaving the profession. Personal lives may also be affected, with increased irritability and reduced ability to manage home responsibilities.8–10 Professionally, MHPs may question their identity, feel incompetent, fear treating suicidal patients, and worry about legal or public consequences.10–14 These experiences can lead to changes in practice—either positive, such as increased vigilance and collaboration, or negative, such as defensive approaches or avoidance of high-risk patients.11,12,14

Seemingly, there is limited emphasis on patient suicide–related training in psychiatry residency and mental health education. Research indicates that many MHPs feel inadequately prepared to handle emotional and professional repercussions of a patient’s suicide, leaving them feeling isolated and ill-equipped to navigate such distressing events.15

Recognizing and understanding the impact of such an event are necessary precursors to identifying how best to support health professionals who experience it. Hence, this study explores the impact of patient suicide on MHPs and assesses the availability and utilization of formal and informal social support systems by MHPs at the time of a patient’s suicide. It also aims to investigate the perception about training required for dealing with such incidents.

METHODS

Study Design

The study utilized a mixed-methods approach involving a survey administered to MHPs through various social media networks, including WhatsApp and email, using Google Forms. Institutional ethics committee approval was received. Along with a link to the Google form, information outlining the aims and objectives of the study was provided. Clicking the link and responding to the survey was considered as providing consent. The online questionnaire was live for 8 weeks (September to October 2023), and a reminder was sent to participants after 3 weeks. Once completed, a new or alternative questionnaire could not be sent by the same participant.

The study included doctors (comprising postgraduate students, senior residents, senior faculty, and private practitioners in psychiatry), psychologists, psychiatric social workers (encompassing trainees and faculty), and mental health nurses working or practicing in India. The minimum sample size was 100 (calculated by formula 4 pq/d2, where p=50%, q=50%, and d =20% of p). However, only 96 responses were received after the second reminder. The final analysis was conducted with the achieved sample. Purposive sampling was used.

A semistructured questionnaire was developed, based on existing literature, and validated by 2 experienced professionals (A.B., C.B.). The questionnaire comprised 6 sections: (1) demographic factors, (2) details of the incident, (3) the effect of the incident on the psychiatrist, (4) the support received, (5) the support required, and (6) the perception about training required to deal with such incidents. MHPs who had not experienced a patient suicide were instructed to skip directly to section 5 after completing section 1. The questions were presented in multiple-choice format, Likert scales, or as short open-ended responses. Anonymity was ensured at all levels. Only the study investigators had access to the data, and caution was taken to exclude any possible personal identifiers from the data and the results.

Statistical Analysis

The data were coded, tabulated, saved, and stored securely in Google Sheets. Descriptive tools such as frequency counts and percentages were used to summarize qualitative variables using Microsoft Excel software. Thematic analysis was employed to interpret the qualitative data derived from responses to 4 specific open-ended questions:

- “What type of emotions did you experience and to what extent? What made you feel that way?”

- “Looking back, do you think the suicide of your patient could have been prevented? What do you think could have been done?”

- “Was there anything that helped you cope with the situation and how?”

- “Was there anything that made your coping with the situation difficult and how?”

The analysis was conducted collaboratively by the authors using the thematic analysis framework by Braun and Clarke,16 ensuring a rigorous and unbiased examination of qualitative data. Independent review of all responses was completed to gain a thorough understanding of the data, and then data were coded and specific themes were identified from specific segments.16 These themes were refined and validated through discussions and revisiting the data to ensure comprehensiveness and accuracy. The thematic analysis resulted in integrating the themes into the overall study findings, with each theme detailed and supported by direct excerpts from respondents to illustrate and substantiate the analysis.

RESULTS

Demographic and Professional Details

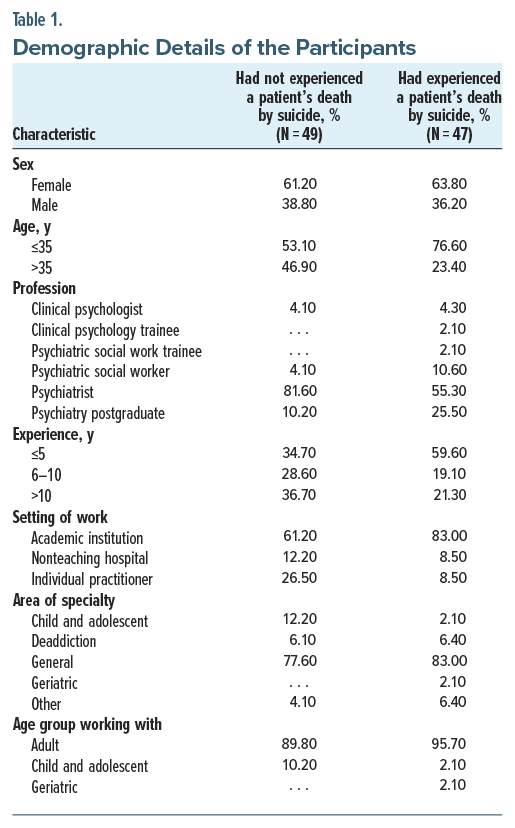

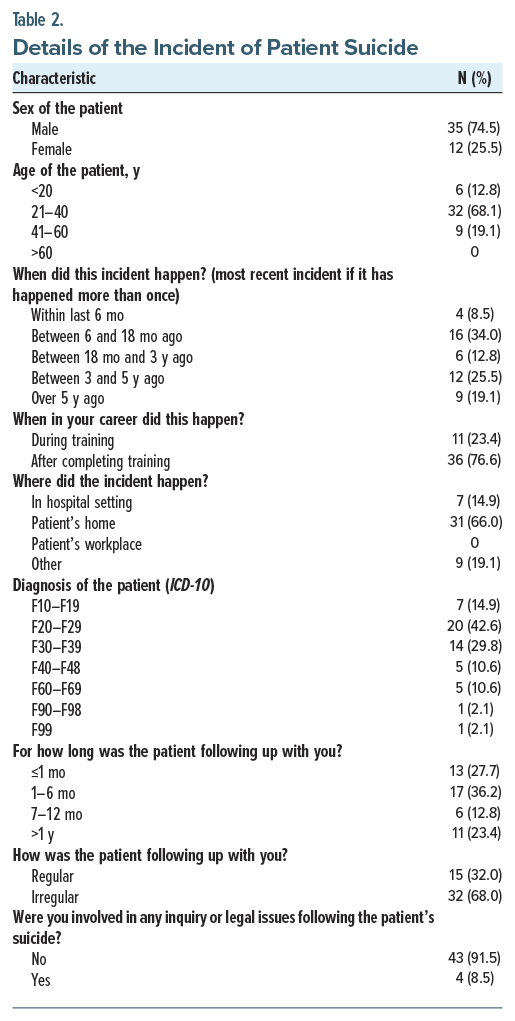

The demographic and professional details of the 96 respondents are provided in Table 1. The details of the incident were explored and are tabulated in Table 2.

Impact on Emotional Well-Being

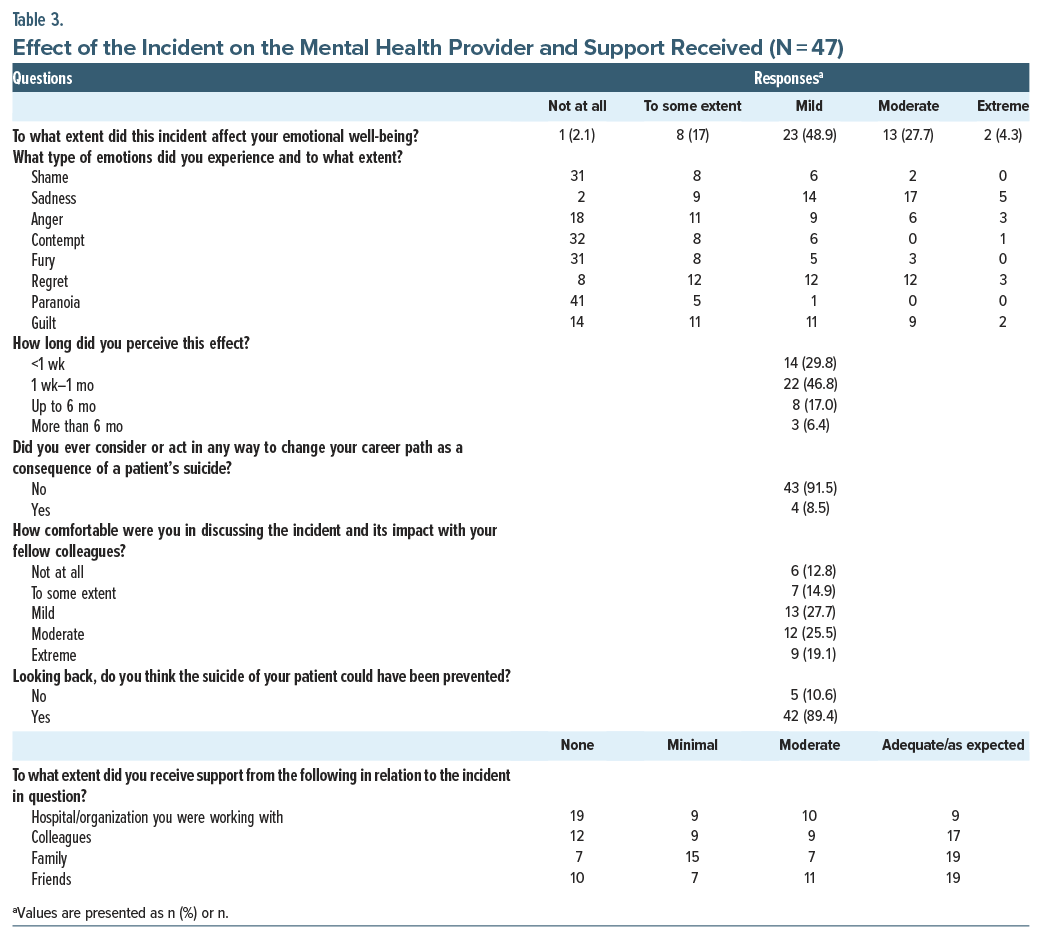

With regard to assessing the effect of the incident on emotional well-being, around one-third of the participants had a moderate-to-extreme effect. Sadness was the most common emotion felt, followed by regret and guilt. These effects were majorly perceived up to 1 month (46.8%). However, around one-fourth of respondents reported ongoing effects up to 6 months or longer, and 8.5% considered changing their career path as a consequence. Only 27.7% were mildly comfortable in discussing the incident and its impact with colleagues, and 89.4% believed that the incident could have been prevented. The majority of respondents reported that they received adequate support from family, friends, and colleagues. However, support from the hospital/organization they were working with was largely lacking (Table 3).

Thematic Analysis of the Open-Ended Questions

“What type of emotions did you experience and to what extent? What made you feel that way?”

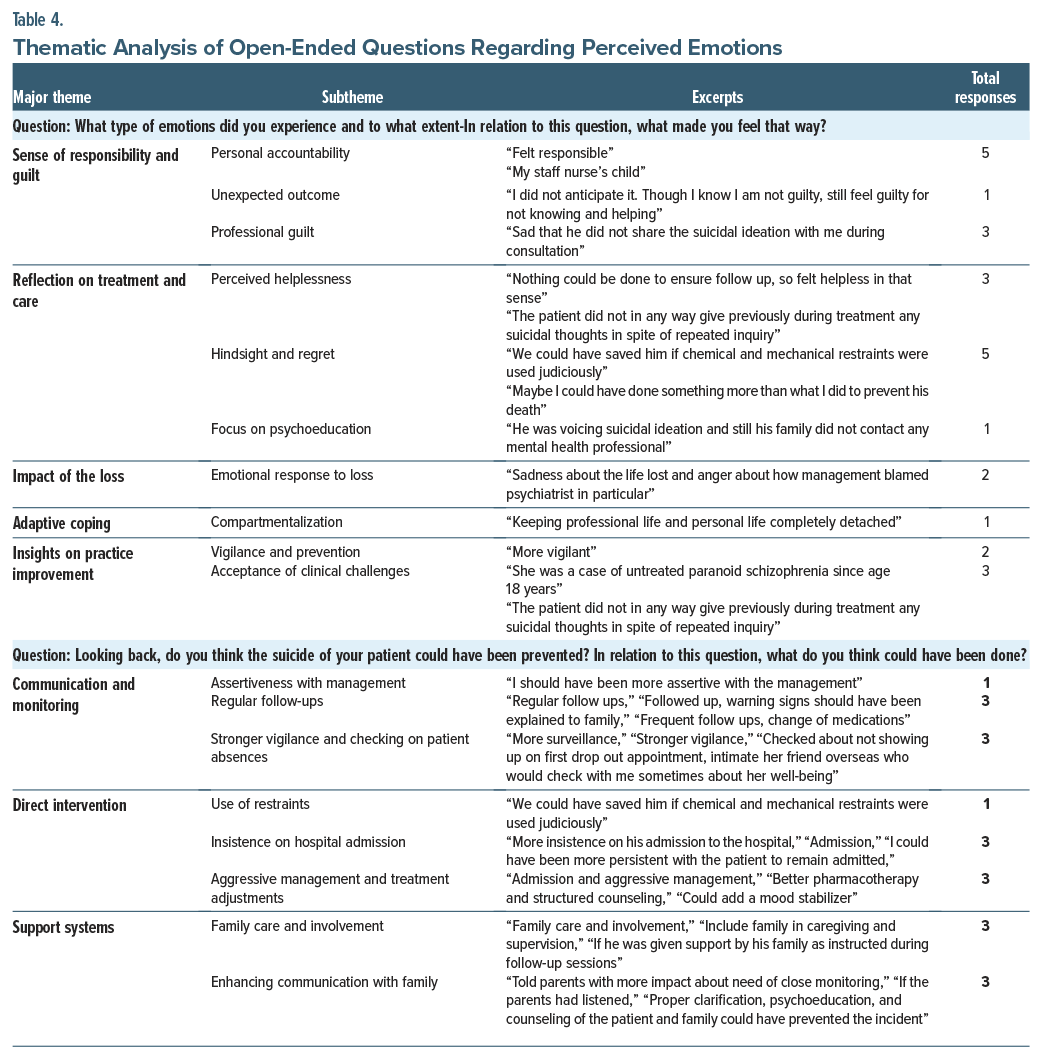

The responses showed that 34.6% of MHPs focused on the themes of sense of responsibility and guilt along with reflection on treatment and care. Subthemes of guilt involved personal accountability (“felt responsible”), unexpected outcome (“I did not anticipate it. Though I know I am not guilty, still feel guilty for not knowing and helping.”), and professional guilt (“Sad that he did not share the suicidal ideation with me during consultation.”). Additionally, 35% of participants felt improvement was needed in communication and monitoring and direct intervention, suggesting that stronger vigilance and proactive measures could have potentially changed the outcomes (Table 4).

“Looking back, do you think the suicide of your patient could have been prevented? What do you think could have been done?”

The participants provided insights on potential interventions. Communication and monitoring improvements were frequently mentioned, including the need for assertiveness with management (“I should have been more assertive with the management”) and ensuring regular follow-ups (“Regular follow-ups, warning signs should have been explained to family”). For direct intervention, suggestions ranged from the judicious use of restraints (“We could have saved him if chemical and mechanical restraints were used judiciously.”) to stronger insistence on hospital admission (“More insistence on his admission to the hospital”). The role of support systems was also underscored, with many emphasizing the need for greater family involvement and education (“Told parents with more impact about the need for close monitoring”), indicating that a comprehensive, multifaceted approach may be key in preventing such tragedies.

Coping With the Incident

“Was there anything that helped you cope with the situation and how?”

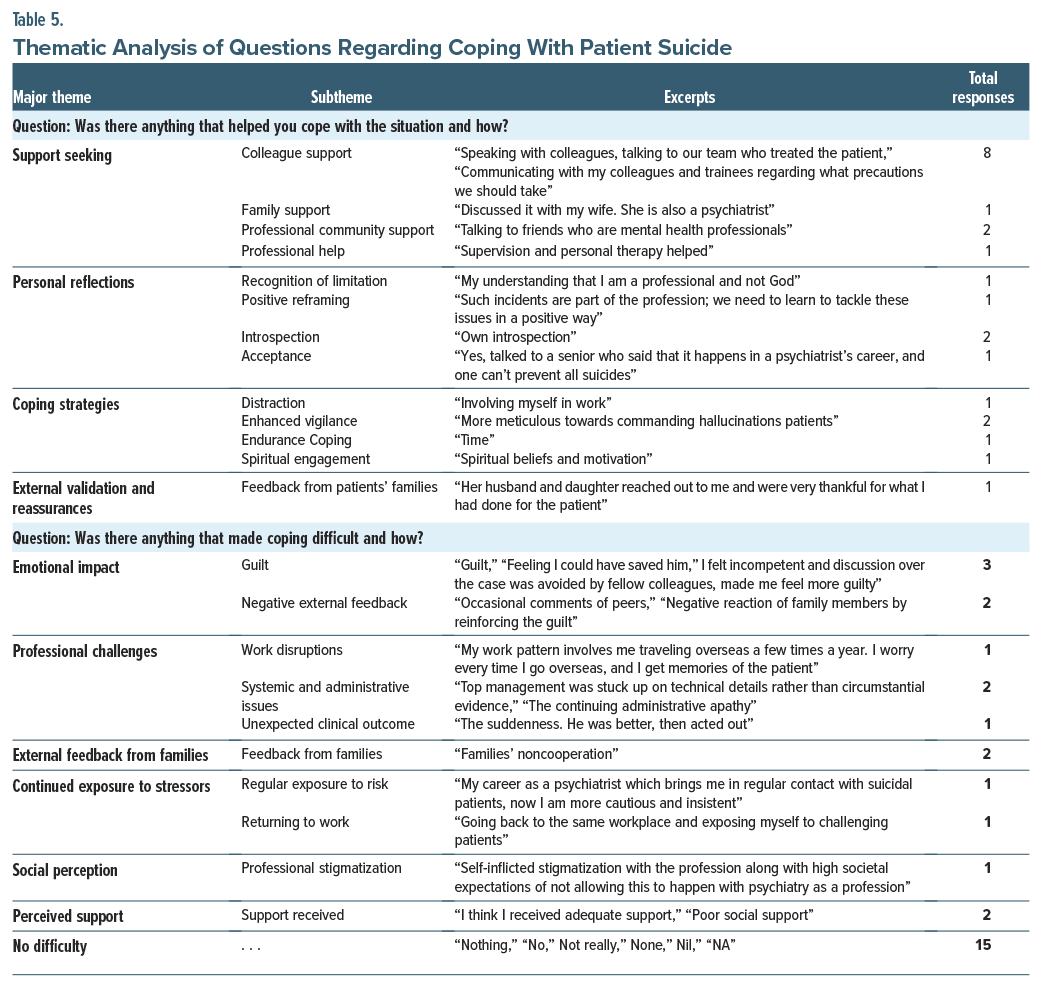

Of the respondents, 52.2% reported that support seeking helped them cope with the situation. Colleague support was emphasized in comments like “Speaking with colleagues, talking to our team who treated the patient” Family support also played a significant role, as one noted, “Discussed it with my wife. She is also a psychiatrist.” Additionally, professional community support (“Talking to friends who are mental health professionals”) and seeking professional help (“Supervision and personal therapy helped”) were valuable. In personal reflections, professionals acknowledged their limitations (“My understanding that I am a professional and not God”) and engaged in positive reframing (“Such incidents are part of the profession, we need to learn to tackle these issues in a positive way.”). Coping strategies varied from distraction (“Involving myself in work”) to spiritual engagement (“Spiritual beliefs and motivation”). External validation, such as feedback from patients’ families (“Her husband and daughter reached out to me and were very thankful for what I had done for the patients.”), also provided comfort (Table 5).

“Was there anything that made your coping with the situation difficult and how?”

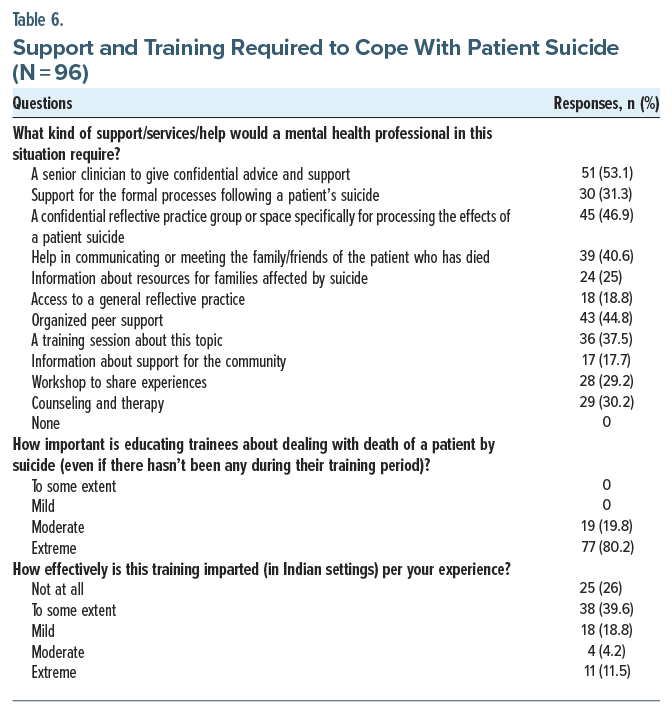

Almost half (48.4%) responded that nothing specific made coping difficult, while the other half felt that emotional impact and professional challenges made the coping difficult. Regarding the kind of support, services, and help that would be required by a MHP to deal with patient suicide, confidential advice from a senior clinician or a confidential reflective practice group were suggested by nearly half of the participants (53.1% and 46.9%, respectively) (Table 6).

“How should the training in relation to dealing with death of a patient by suicide be incorporated in psychiatry residency?”

Around 80% responded that this topic should be included in the curriculum for postgraduate training, workshops and seminars. Approximately 15% responded that trainees should be taught the coping methods neccesary in dealing with such circumstances.

DISCUSSION

The current study presents a comprehensive look into the impact of patient suicide on MHPs, especially psychiatrists and psychiatry trainees. The demographic profile showed a predominance of female respondents, and psychiatrists formed the largest professional group. The demographics closely align with those observed in the study by Gulfi et al,17 wherein 54.4% of participants were female and the majority were psychiatrists (74.8%).

Patient suicide was not an uncommon experience, as 51% of participants confirmed that they had a patient under their treatment who had died by suicide, consistent with findings from Ruskin et al18 and Chemtob et al,5 wherein around half of the MHPs had encountered such an incident. A larger study by Castelli et al19 found a slightly higher prevalence (58%) among institutional MHPs.

Regarding the details of the incident, the majority of the patients were male and aged between 20 and 40 years, with the predominant diagnosis being psychotic illnesses, followed by affective disorders. These findings were similar to those of Pieters et al,20 in which the majority of patients were male, younger than 40 years, and diagnosed with depressive psychotic disorder.

It was found that, 76.6% of respondents experienced the suicide of a patient after completing their training, which contrasts with another study20 in which the majority (78%) encountered such incidents during their training period. Ruskin et al18 reported that 31% of respondents had experienced the suicide of a patient while they were still in training. Though there is a dearth of literature for comparison, this difference might also reflect variations between institutional settings and private practice. In institutional settings, the support systems and supervision available during training could dilute the immediate impact of patient suicides, whereas in private practice where professionals practice with higher autonomy, the burden of such incidents may be more intensely felt after training is completed. Most of the time (66%), the incident occurred in the patient’s home, which contrasts with the findings of Pieters et al,20 in which 68% (n=54) were inpatients. This suggests that suicide occurring outside of controlled environments like hospitals might reflect challenges in post-discharge care and the need for stronger follow-up and community-based support systems; 21% of the patients were following up for 3 months or less and ∼68% had irregular follow ups. Gulfi et al17 reported more intense reactions observed among professionals who felt responsible for and close to the deceased patient. This may be related to the duration of the therapy and to the fact that MHPs were still in contact with the patient at the time of suicide and felt that their relationship was intense.17

Approximately one-third of participants reported a moderate-to-severe impact on their emotional well-being, with sadness being the most commonly reported emotion, followed by feelings of regret and guilt. These feelings persisted for a while, with 17% reporting that they experienced these effects for as long as 6 months, and some of them even considered changing their career path as a consequence of this incident. These results mirror findings from Ruskin et al,18 wherein 71% felt helpless, 55% experienced horror, and 44% experienced anxiety. Literature reviews by Lafayette and Stern21 and Foley and Kelly3 support the notion that MHP reactions to patient suicide can be profound and long-lasting, resembling grief responses and, in some cases, posttraumatic stress symptoms. These experiences may also lead to defensive clinical practices, including more conservative risk assessments and increased documentation.

Comfort with discussing the incident was limited, with only 27.7% feeling mildly comfortable sharing it with colleagues. This finding echoes that of Ruskin et al,18 where 27% of participants reported being unable to seek help, reflecting the stigma or discomfort around addressing such distressing professional events.

Qualitative data analysis revealed that 34.6% of responses centered on a sense of responsibility and guilt, along with reflections on the treatment and care provided. Guilt was categorized into subthemes such as personal accountability, unexpected outcomes, and professional guilt, emphasizing a belief that the suicide represented a failure on their part. This aligns with Ting et al,22 who noted that many MHPs view patient suicide as evidence of professional inadequacy. About 35% of participants felt that better communication, monitoring, and direct intervention could have prevented the suicide, including being more assertive about hospitalization, judicious use of restraints, and ensuring regular follow-up. Chemtob et al5 found that younger age and less training were associated with greater emotional impact, suggesting trainees may be more vulnerable.

Professionally, such incidents often lead to significant changes in clinical practice, including increased documentation, lower thresholds for hospitalization, and more defensive therapeutic decisions.8,9 Coping strategies were varied: 52.2% relied on support seeking through colleagues, family, or the professional community. Others employed personal reflections, distraction, enhanced vigilance, or spiritual beliefs. These findings are consistent with Pieters et al,20 who emphasized the role of supervisory and peer support. Some professionals felt isolated, underscoring the importance of accessible institutional support. Gulfi et al17 similarly found that those who had sufficient support experienced less distress and fewer professional disruptions. Ting et al22 also emphasized the protective role of professional support in such contexts.

All respondents in our study agreed on the importance of training in managing the impact of patient suicide, but only 11.5% felt that existing training in India was extremely effective. Pieters et al20 similarly reported that despite the frequency of such incidents, less than half of professionals had received formal training. Only a small percentage had been taught to cope with the psychological and professional consequences of a patient’s suicide. Globally, studies show that only 20%–25% of psychiatry trainees receive adequate education in this domain.3,23,24

Those who did receive post-suicide management training found it helpful, mirroring the positive reception of such programs in studies from other countries.5,9 Given the emotional and professional ramifications of patient suicide, these findings strongly advocate for integration of structured and mandatory training on the topic in postgraduate psychiatry curricula. Formal programs could offer not only preventive frameworks but also crucial support mechanisms for navigating the aftermath, ultimately safeguarding the well-being of MHPs and improving patient care.

CONCLUSION

The suicide of a patient has a profound impact on MHPs, affecting their emotional well-being, professional identity, and susceptibility to burnout, while also posing potential legal challenges. Creating supportive workplace environments and strong professional networks is crucial in addressing these challenges. Psychiatry training programs should incorporate education on coping mechanisms and burnout prevention, while fostering open discussions among peers. These initiatives can strengthen MHPs’ resilience and enhance the quality of mental health care. However, this study has certain limitations, including a small sample size, unequal representation of different MHP groups, and potential recall bias due to its retrospective design. Future research may explore the long-term psychological and professional impact of patient suicide on MHPs. Studies with larger, more representative samples can help identify group-specific needs and coping mechanisms. Prospective, longitudinal designs would provide deeper insight into recovery trajectories. Additionally, evaluating the effectiveness of structured support programs and resilience-building interventions can inform best practices. Exploring cultural, institutional, and systemic factors influencing MHP responses to patient suicide will also be crucial in developing tailored, evidence-based strategies to support their well-being and professional functioning.

Article Information

Published Online: November 20, 2025. https://doi.org/10.4088/PCC.25m03995

© 2025 Physicians Postgraduate Press, Inc.

Submitted: May 4, 2025; accepted July 25, 2025.

To Cite: Singh S, Raut NB, Bhardwaj A, et al. Impact of patient suicide on mental health professionals. Prim Care Companion CNS Disord 2025;27(6):25m03995.

Author Affiliations: Institute of Human Behaviour and Allied Sciences, Delhi, India (Singh); Lady Hardinge Medical College, Delhi, India (Raut); All India Institute of Medical Sciences, Delhi, India (Bhardwaj); Pt. B.D. Sharma UHS, Rohtak, India (Malik).

Corresponding Author: Yogender Malik, MD, DNB, Pt. B.D. Sharma UHS, Rohtak, India ([email protected]).

Relevant Financial Relationships: None.

Funding/Support: None.

Acknowledgement: The authors would like to acknowledge all the participants who shared their insights and experiences.

Clinical Points

- Patient suicide can cause lasting emotional and professional distress in mental health professionals (MHPs) due to their unique relationship with the patient.

- Confidential peer support and structured debriefing can ease guilt and reduce burnout in MHPs.

- Integrating structured modules in psychiatry training programs focusing on the emotional aftermath, legal implications, coping strategies, and support pathways after patient suicide through workshops or reflective spaces may help build preparedness and resilience.

References (24)

- World Health Organization. Suicide in the World: Global Health Estimates. 2019. https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/suicide-in-the-world. Accessed October 2024.

- Andriessen K, Krysinska K, Hill NT, et al. Effectiveness of interventions for people bereaved through suicide: a systematic review of controlled studies of grief, psychosocial and suicide-related outcomes. BMC psychiatry. 2019;19:49–55. PubMed CrossRef

- Foley SR, Kelly BD. When a patient dies by suicide: incidence, implications and coping strategies. Adv Psychiatric Treat. 2007;13(2):134–138. CrossRef

- Feigelman W, Cerel J, McIntosh JL, et al. Suicide exposures and bereavement among American adults: evidence from the 2016 general social survey. J Affect Disord. 2018;227:1–6. PubMed CrossRef

- Chemtob CM, Hamada RS, Bauer G, et al. Patients’ suicides: frequency and impact on psychiatrists. Am J Psychiatry. 1988;145(2):224–228. PubMed CrossRef

- Dutheil F, Aubert C, Pereira B, et al. Suicide among physicians and health-care workers: a systematic review and meta-analysis. PloS one. 2019;14(12):e0226361. PubMed CrossRef

- Stanley IH, Hom MA, Joiner TE. A systematic review of suicidal thoughts and behaviors among police officers, firefighters, EMTs, and paramedics. Clin Psychol Rev. 2016;44:25–44. PubMed CrossRef

- Alexander DA, Klein S, Gray NM, et al. Suicide by patients: questionnaire study of its effect on consultant psychiatrists. BMJ. 2000;320(7249):1571–1574. PubMed CrossRef

- Dewar I, Eagles J, Klein S, et al. Psychiatric trainees’ experiences of, and reactions to, patient suicide. Psychiatr Bull. 2000;24(1):20–23. CrossRef

- James DM. Surpassing the quota: multiple suicides in a psychotherapy practice. Women Ther. 2004;28(1):9–24. CrossRef

- Ellis TE, Patel AB. Client suicide: what now? Cognitive Behav Pract. 2012;19(2):277–287. CrossRef

- Campbell C, Fahy T. The role of the doctor when a patient commits suicide. Psychiatr Bull. 2002;26(2):44–49. CrossRef

- Collins JM. Impact of patient suicide on clinicians. J Am Psychiatric Nurses Assoc. 2003;9(5):159–162. CrossRef

- Farberow NL. The mental health professional as suicide survivor. Clin Neuropsychiatry. 2005;2(1):13–20.

- Lerner U, Brooks K, McNiel DE, et al. Coping with a patient’s suicide: a curriculum for psychiatry residency training programs. Acad Psychiatry. 2012 Jan;36(1):29–33. PubMed CrossRef

- Braun V, Clarke V. Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qual Res Psychol. 2006;3(2):77–101. CrossRef

- Gulfi A, Castelli Dransart DA, Heeb JL, et al. The impact of patient suicide on the professional practice of Swiss psychiatrists and psychologists. Acad Psychiatry. 2016;40(1):13–22. PubMed CrossRef

- Ruskin R, Sakinofsky I, Bagby RM, et al. Impact of patient suicide on psychiatrists and psychiatric trainees. Acad Psychiatry. 2004 Jun;28(2):104–110. PubMed CrossRef

- Castelli Dransart DA, Heeb JL, Gulfi A, et al. Stress reactions after a patient suicide and their relations to the profile of mental health professionals. BMC Psychiatry. 2015;15:1–9. PubMed CrossRef

- Pieters G, De Gucht V, Joos G, et al. Frequency and impact of patient suicide on psychiatric trainees. Eur Psychiatry. 2003;18(7):345–349. PubMed CrossRef

- Lafayette JM, Stern TA. The impact of a patient’s suicide on psychiatric trainees: a case study and review of the literature. Harv Rev Psychiatry. 2004;12(1):49–55. PubMed CrossRef

- Ting L, Jacobson JM, Sanders S. Available supports and coping behaviors of mental health social workers following fatal and nonfatal client suicidal behavior. Soc Work. 2008;53(3):211–221. PubMed CrossRef

- Whitmore CA, Cook J, Salg L. Supporting residents in the wake of patient suicide. Am J Psychiatry Residents’ J. 2017;12(1):5–7. CrossRef

- Prabhakar D, Balon R, Anzia JM, et al. Helping psychiatry residents cope with patient suicide. Acad Psychiatry. 2014;38(5):593–597. PubMed CrossRef

Enjoy this premium PDF as part of your membership benefits!