Abstract

Context: Antipsychotic medications are associated with significant metabolic risks including weight gain, lipid abnormalities, and glucose intolerance. Incretin therapies could have massive potential to benefit patients affected by antipsychotic-induced weight gain. However, patients with psychiatric disorders were often excluded from clinical trials, leaving safety and efficacy in this population largely unexplored.

Evidence Acquisition: A narrative review was conducted to evaluate the data surrounding use of incretin therapies to mitigate metabolic consequences of antipsychotics and to review general safety and efficacy data relevant to prescribing of these agents to be distilled for the psychiatric provider. Package inserts, relevant clinical guidelines, and cardiometabolic outcomes trials were reviewed in developing the prescribing guide.

Results: Limited data suggest that incretin therapies may be effectively utilized in patients with psychiatric conditions. A prescribing guide and algorithm were developed and include information on selecting an agent based on comorbidities, dosing and prescribing, contraindications, and clinical pearls that may be of use to providers who wish to utilize incretin therapies in patients with psychiatric comorbidities.

Conclusion: Incretin therapies are highly effective medications for diabetes and weight management in the general population. While additional monitoring may be warranted in patients with psychiatric conditions, these agents are potentially effective and safe for use in treating obesity or overweight and diabetes in this population.

Prim Care Companion CNS Disord 2025;27(5):25nr03924

Author affiliations are listed at the end of this article.

Antipsychotic medications are commonly used in psychotic disorders (schizophrenia spectrum disorders) and mood disorders (bipolar disorder, depression). Second-generation antipsychotics are associated with significant metabolic side effects including weight gain, dyslipidemia, and impaired glucose tolerance.1 These consequences may lead to serious comorbidities—ie, rates of type 2 diabetes mellitus (T2DM) are heightened in patients with psychiatric disorders, due in part to metabolic consequences from antipsychotic medication.2–4 In particular, olanzapine and clozapine have major established metabolic effects, which are believed to be, in part, due to increased appetite and decreased satiety signaling.5,6 Weight gain is associated with both physical and psychological consequences.7,8 Patients with mood and psychotic disorders also independently have a heightened risk of death from cardiovascular (CV) causes, the risk of which is significantly influenced by the presence of T2DM and metabolic syndrome.8 In part due to these risks, the life expectancy of patients with schizophrenia or bipolar disorder is approximately 10–20 years less than those without these conditions.9 Therefore, management of metabolic conditions is necessary to mitigate risk of CV disease (CVD) and ensure high quality of life for patients with mood and psychotic disorders.

Traditionally, agents utilized in the management of antipsychotic-induced metabolic syndrome were limited due to small sample size and shorter duration of clinical trials. Most of the evidence surrounds metformin, which is associated with a weight decrease of 3–4 kg.10 Topiramate and glucagon-like peptide 1 receptor agonists (GLP-1 RAs) are additional options briefly discussed in the 2020 American Psychiatric Association Practice Guideline for the Treatment of Patients With Schizophrenia, however, are not established as a guideline-recommended option.11 Incretin therapies are an increasingly popular medication class with a growing list of indications. Incretin therapies used for weight management include GLP-1 RAs (ie, dulaglutide, liraglutide, semaglutide) and dual agonists of GLP-1 and glucose-dependent insulinotropic polypeptide (GIP) receptors (ie, tirzepatide). These agents could have massive potential to benefit patients affected by antipsychotic-induced weight gain, as they are more potent than older agents used for weight loss, and many have additional cardiometabolic and renal benefits.12–17 In some clinical trials of incretin therapies for obesity (ie, liraglutide and semaglutide), patients were determined to have active or unstable major depressive disorder (MDD) or other severe psychiatric disorders, defined as schizophrenia, bipolar disorder, or other serious mood or anxiety disorders within the last 2 years; however, these criteria were heterogeneous across trials.12–18 For instance, in the Small Changes and Lasting Effects (liraglutide) trial and SURMOUNT-1 (tirzepatide) trials, patients were excluded if they were taking medications that may contribute to weight gain including tricyclic antidepressants, mirtazapine, paroxetine, and several antidepressants and mood stabilizers.12 Initial obesity-focused trials of tirzepatide tended to be more inclusive, only excluding patients with a history of known drug abuse, alcohol abuse, or psychiatric disorder that may preclude the patient from following and completing the protocol.13,14,19 The initial exclusions related to mental health conditions may have resulted in limited comfort in using these agents in patients with psychiatric disorders.

Despite this, several studies exist suggesting that incretin therapies can be safely used to treat metabolic consequences of antipsychotics including antipsychotic-induced weight gain without heightened psychiatric adverse effects, and evidence is present suggesting their use as a potential treatment option in this population.20–24 This article provides a review of the available data concerning use of incretin therapies in the management of antipsychotic-induced weight gain as well as an algorithm for use in selecting among incretin therapies for the treatment of T2DM or obesity in patients with psychiatric comorbidities.

METHODS

A narrative review was conducted utilizing the PubMed database of literature published in English through November 15, 2024. Search terms included GLP-1 receptor agonist, exenatide, semaglutide, liraglutide, tirzepatide, dulaglutide, retatrutide, bipolar disorder, schizophrenia, schizoaffective disorder, psychotic disorders, suicidality, suicide ideation, antipsychotic-induced weight gain, antipsychotic-induced metabolic syndrome, and diabetes mellitus. Studies were included if they provided relevant results on efficacy outcomes related to weight management or diabetes, or if they provided relevant safety outcomes related to psychiatric events such as worsening of psychiatric conditions or suicidality. Additional resources including relevant clinical practice guidelines, package inserts, and cardiovascular and other metabolic outcomes trials for each medication were also reviewed for the purpose of developing the prescribing guide. Review of package inserts was necessary to evaluate potential drug interactions, contraindications, and adverse effects. Review of clinical trials and the American Diabetes Association Standards of Care were necessary to develop guidance related to cardiometabolic comorbidities relevant to the selection of incretin therapies. Clinicaltrials.gov was reviewed to determine ongoing trials related to incretin therapies and antipsychotic-induced weight gain.

RESULTS

Efficacy in Psychiatric Populations

Studies evaluating the efficacy of incretin therapy in psychiatric disorders vary, with much of the data coming from studies in which patients were treated with an antipsychotic. Two systematic reviews and 1 meta-analysis are available summarizing the efficacy of incretin therapies in improving metabolic parameters including glucose tolerance, low-density lipoprotein, body weight, waist circumference, and body mass index (BMI) in patients with psychiatric conditions.21,22,24

In reviewing the individual studies included in these meta-analyses and systematic reviews, additional insight can be gained into how to apply these data to the psychiatric population. In a small trial of clozapine-treated patients with obesity and with or without T2DM, those who received exenatide compared to usual care experienced more weight loss (4.16 kg more than placebo), as well as greater reductions in BMI, fasting plasma glucose, and hemoglobin A1c (HbA1c) at 24 weeks. After cessation of exenatide, these benefits were not sustained.23 This finding suggests the need for long-term use of incretin therapies to maintain weight loss and metabolic benefits. This is in line with the recently adopted practice of treating obesity as a chronic disease, rather than a temporary condition. Patients with antipsychotic-induced weight gain may warrant similar long-term treatment.

In a case series of patients treated with antipsychotics who experienced inadequate weight loss on metformin, treatment with a mean semaglutide dose of 0.71 mg/week resulted in mean weight loss of 4.56 kg, 5.16 kg, and 8.67 kg at follow-up periods of 3, 6, and 12 months, respectively.25 Participants in the case series had a variety of diagnoses including seasonal affective disorder, bipolar disorder, borderline personality disorder, and MDD.25 They were treated with various antipsychotics including brexpiprazole, aripiprazole, clozapine, olanzapine, and lurasidone.25 While the authors state that numerical, nonstatistically significant reductions were observed in other metabolic parameters including HbA1c, cholesterol, and measures of insulin resistance, these values were not reported.25 Treatment with semaglutide appeared to be safe and effective, with gastrointestinal disturbances the most commonly reported adverse drug event (ADE).25 This study demonstrates that semaglutide may be a useful agent in patients who would benefit from additional weight loss after inadequate weight loss with the current standard of care. Given that this study featured only a few patients, future larger, adequately powered controlled studies evaluating the impact of semaglutide on various cardiometabolic parameters are warranted.

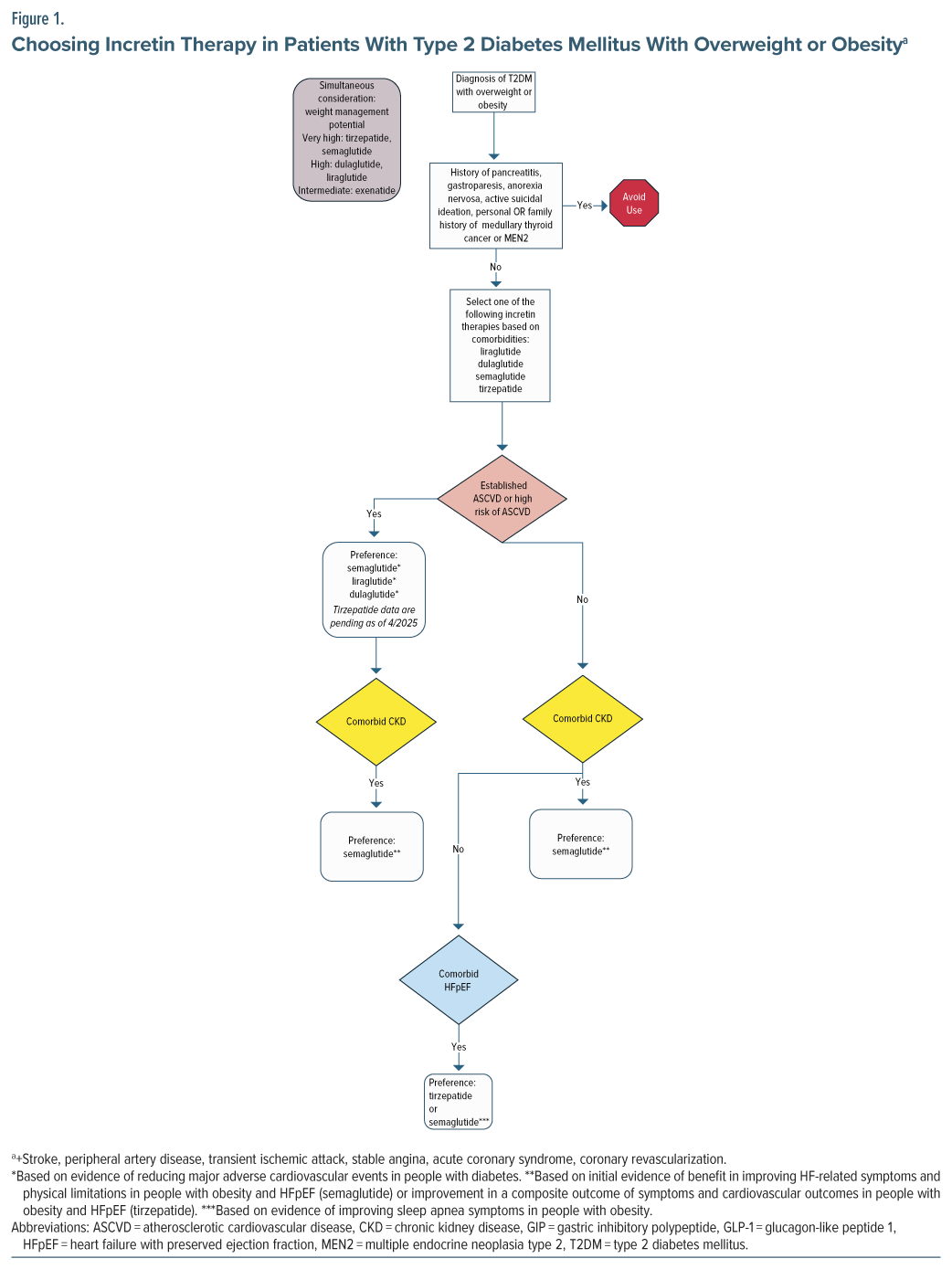

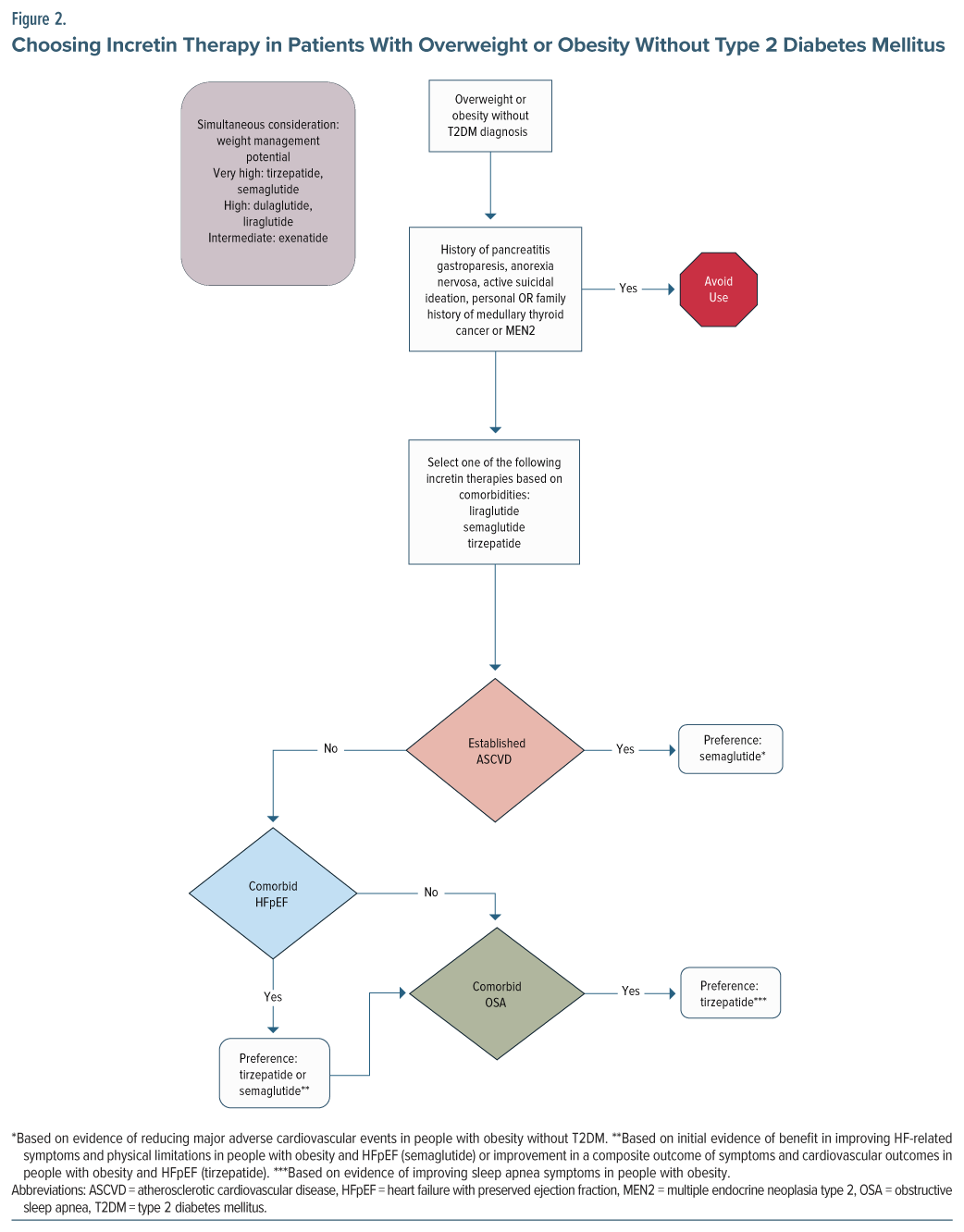

In another single case, a patient with schizophrenia was initially treated with dulaglutide for diabetes.26 She was switched to treatment with semaglutide 0.5 mg once weekly, counseled on significant lifestyle interventions, and provided with cognitive-behavioral therapy focusing on lifestyle modifications for weight.26 This intervention resulted in a weight loss >10 kg over 6 months.26 The authors report that the intervention also resulted in her HbA1c becoming “well controlled” from a previous value above 10.0%.26 As this case suggests, there are differences in potency and efficacy of the various incretin therapies. Semaglutide tends to result in greater weight loss than dulaglutide. Therefore, the choice of incretin therapy should be individualized by patient comorbidities and the amount of weight loss desired (Figure 1 and Figure 2).

An ongoing clinical trial (SemaPsychiatry) seeks to evaluate the use of semaglutide in patients with schizophrenia and diabetes or prediabetes treated with clozapine or olanzapine over 26 weeks.27 The primary outcome is change in baseline HbA1c.27 Additional metabolic endpoints include markers of metabolic syndrome including body weight and waist and hip circumference. This randomized controlled trial should further elucidate the safety and efficacy of semaglutide in patients on antipsychotics associated with significant weight gain.27

No trials were found evaluating use of tirzepatide—a dual agonist of GLP-1 RA and GIP—in patients with psychiatric conditions. Given the impressive efficacy of tirzepatide in treating obesity and overweight and treating and even preventing diabetes, its use may still be considered despite a lack of evidence in this specific population.13,14,28

Psychiatric Adverse Effects

The potential benefits associated with utilizing incretin therapy to manage metabolic syndrome in patients with psychiatric disorders must also be met with vigilant consideration of potential psychiatric-related ADEs. This is especially important in this patient population, as rates of death by suicide are higher than in the general population.29

Suicidality reporting has been assessed in 2 evaluations of US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) Adverse Event Reporting System (FAERS) databases. One review investigated reports of suicide ideation, “depression/suicidal,” suicidal behavior, and suicide attempt between 2005 and 2023.20 Incretin therapy adverse event reporting was compared to 2 separate controls, metformin and insulin.20 Semaglutide and liraglutide had significantly higher reporting odds ratios (RORs) compared to metformin or insulin for suicide ideation, depression/suicidal, suicide attempt, and completed suicide.20 Dulaglutide, exenatide, lixisenatide, and tirzepatide did not demonstrate a significantly higher ROR.20 It is possible that heterogeneity exists among these agents. However, the lack of consistent data calls into question whether the uptick in adverse events noted is merely reporting bias. Ultimately, causality is unable to be determined by these reports, as postmarketing data have very little ability to mitigate confounders and prevent different types of bias.

A second FAERS review evaluated incretin therapies from 2004 to 2023 and captured reports of psychiatric adverse events.30 Between 2004 and 2023, out of the total ADEs reported to FAERS for exenatide, liraglutide, lixisenatide, dulaglutide, semaglutide, and tirzepatide, 4.55% were related to psychiatric symptoms (out of a total of 181,238 total ADEs reported).30 Of these psychiatric reported ADEs, 3,948 were associated with exenatide, 1,152 (13.98%) with liraglutide, 12 (0.15%) with lixisenatide, 1,833 (22.25%) with dulaglutide, 1,033 (12.54%) with semaglutide, and 262 (3.18%) with tirzepatide.30 Unfortunately, the total number of adverse events was not reported individually for each agent in this study. Therefore, comparisons to the general frequency of other adverse events cannot be made for each drug. These possible psychiatric-related ADEs were compared to all medications in the FAERS database, and of these, nervousness, self-induced vomiting, binge eating, fear of eating, and fear of injection were shown to have significantly higher odds of occurrence with incretin therapy.30 Significantly higher odds of sleep disorder (insomnia type) and eating disorder were also demonstrated.30 Analysis from the FAERS database indicated that the median time of onset for these possible adverse events presenting was 31 days.30 These reports were compared to all other pharmacotherapy reported in FAERS, and no significant difference was found.30 At this time, the data surrounding increased risks of psychiatric conditions remain conflicting, and thus, incretin therapy initiation in this population will likely warrant some monitoring to ensure continued stability, particularly in the first month of initiation. To optimize safety, we recommend avoiding initiating incretin therapy in patients with active suicidal ideation.

Psychiatric Drug Interactions

In general, there are few drug interactions with incretin therapies. However, a single case report described worsening of paranoid delusions in a patient with diabetes and schizophrenia treated with ziprasidone who was initiated on semaglutide 1 mg for weight loss.31 The delusions improved when ziprasidone was increased to the typical maximum dose (160 mg) though only given nightly (instead of twice daily).31 Interestingly, it seems that the standard starting dose of semaglutide 0.25 mg was not utilized. Two weeks after dose increase to semaglutide 2 mg, symptoms worsened again, resulting in a decrease back to 1 mg.31 While the exact mechanism is unknown, it was suggested that this may have occurred due to delayed gastric emptying, which may affect ziprasidone absorption.31,32 Changes in gastric motility typically normalize with time after initiation of incretin therapy. It is unknown how the effect of semaglutide may have changed over time, as the 2-mg dose was decreased immediately upon symptom presentation.31 It may be prudent to only consider initiation of incretin therapies in patients whose psychiatric symptoms are stable and to closely monitor for worsening of symptoms in patients taking antipsychotics whose absorption is affected by food (ie, ziprasidone, lurasidone).33,34

Eating Disorders

An additional consideration is that eating disorders are not uncommon in patients with serious psychiatric conditions.35,36 In patients with comorbid eating disorders, safety of use varies based on the etiology of the disorder. For instance, there is growing evidence that incretin therapies are not just safe but also may provide a benefit in binge-eating disorder, as they may target different reward pathways that facilitate binge-eating behaviors.37–39 However, in patients with anorexia nervosa, the use of these agents may be part of the psychiatric disorder that perpetuates the maladaptive behaviors and processes. Further, while patients with bulimia nervosa may present with higher BMIs, there may be a potential that the misuse of incretin therapy may facilitate the purging maladaptive behaviors. Careful consideration and clinical judgment are necessary when screening for eating disorders in patients with obesity and in choosing whether to prescribe incretin therapy in patients with an eating disorder diagnosis.

Chronic Disease State Considerations

Several incretin therapies have demonstrated beneficial effects on a variety of comorbid conditions in both patients with diabetes and obesity. However, these benefits are not necessarily consistent across each agent. Therefore, FDA indications for these agents are heterogeneous. When selecting incretin therapy, providers must consider a patient’s comorbid chronic conditions including T2DM, obesity, chronic kidney disease (CKD), atherosclerotic CVD (ASCVD), obstructive sleep apnea, and heart failure (HF). Figure 1 attempts to apply the data surrounding these comorbidities to optimize the selection of incretin therapy.

Providers should consider which agents have proven benefits in each disease state when selecting an agent. For patients with T2DM, several agents have shown cardioprotective and renoprotective potential in CV outcomes trials (CVOTs) and should be preferenced in patients with ASCVD, high ASCVD risk, or renal disease, as outlined in the American Diabetes Association Standards of Care.40 These include semaglutide, liraglutide, and dulaglutide. Of note, since publication of the 2025 American Diabetes Association Standards of Care, a new trial with oral semaglutide has demonstrated positive outcomes in reducing major adverse cardiac events in patients with diabetes at high risk of CV events (existing ASCVD and/or CKD).41 Tirzepatide’s CVOT is ongoing. In terms of renal protection, semaglutide has the strongest data, with a dedicated renal outcomes trial.42 In patients with obesity and without T2DM, injectable semaglutide is thus far the only incretin therapy with proven benefit in reducing the risk of ASCVD events; thus, it should be considered in patients with a history of ASCVD.43 With regard to HF with preserved ejection fraction (HFpEF), initial data suggest a benefit of tirzepatide and semaglutide in patients with obesity. A single trial evaluated tirzepatide for HFpEF, which included patients with and without T2DM, and showed improvement in a composite outcome of death from CV causes or worsening HF symptoms of HFpEF when compared to placebo.44 With semaglutide, 2 trials have been conducted: 1 in patients with T2DM and 1 without.45,46 Both showed improvement in HFpEF symptoms with semaglutide compared to placebo.45,46 While additional trials in patients with HFpEF are warranted before definitive statements can be made regarding the benefits of various incretin therapies in HFpEF, providers may wish to consider the positive results for semaglutide and tirzepatide when choosing among incretin therapies. However, we have chosen to include these preliminary data for consideration in our algorithms and to preference these agents when clinically appropriate.

Incretin therapies also differ in their weight loss potency. Agents with the highest efficacy for weight loss include tirzepatide and injectable semaglutide, followed by dulaglutide and liraglutide.47 Tirzepatide appears to be the most effective agent thus far in terms of weight loss, with participants losing up to nearly 25% of their body weight across 72 weeks.14 In clinical trials of tirzepatide, treatment is associated with major weight reductions, as high as over 25% across various studies.13,14,18,19 Liraglutide and dulaglutide are not as powerful in terms of weight management potential but tend to produce more weight loss than exenatide. While these agents have impressive results in the general population, they appear similarly effective in the management of antipsychotic-induced weight management.21,25 Retatrutide, a triple hormone-receptor agonist (GLP1, GIP, and glucagon receptors), has demonstrated high potential for weight loss in phase 2 studies of patients with obesity (up to 24% body weight loss at 48 weeks).17 This agent is still under investigation in larger phase 3 trials.48,49

Patients with psychiatric conditions are encouraged to engage in lifestyle modifications to prevent weight gain associated with antipsychotic medications.11 Physical activity and associated structured interventions are effective in this population.50 However, people with psychiatric conditions may face additional challenges in implementing these changes. Challenges may include limited resources (ie, financial barriers, transportation issues), impaired cognition, and avolition. Providers should offer continued coaching and encouragement for healthy lifestyle habits including ≥150 minutes per week of moderate physical activity and a balanced diet.51 These lifestyle interventions overall align with recommendations for patients with antipsychotic-related weight gain. While these medications are most effective when combined with lifestyle interventions, inability to successfully engage in these interventions should not necessarily be a reason to withhold therapy given the significant consequences of obesity.52

There are no data at this time regarding optimal duration of therapy in antipsychotic-induced weight gain. After cessation of incretin therapy, significant weight regain is common.18,53 Therefore, patients may require long-term utilization of these agents to sustain weight loss. Patients and providers should be educated that obesity and overweight is a chronic disease state that may warrant lifelong management.54 If switching an antipsychotic to a more metabolically neutral agent (for instance olanzapine to aripiprazole), it may be worth reevaluating incretin therapy use if the patient has significant metabolic improvements on a new therapy.

Prescribing Considerations

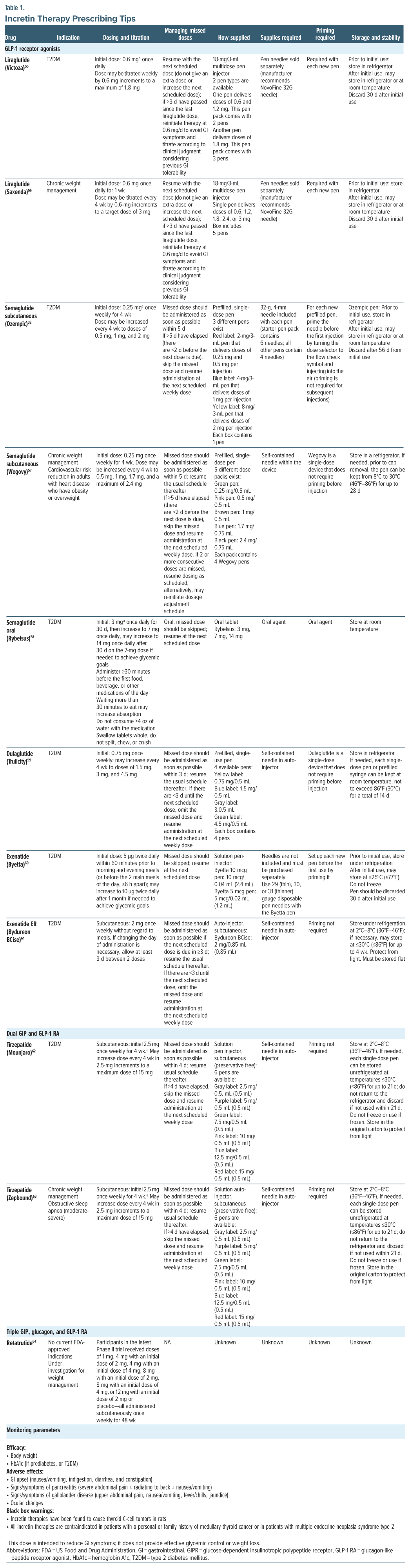

Providers who wish to prescribe incretin therapies should be aware of the differences in dosing, frequency of administration, uptitration schemes, management of missed doses, pen devices, necessary supplies (ie, needles), and administration. In reviewing package inserts, these items are summarized for ease in Table 1.55–63

CONCLUSION

Despite limited data, available studies suggest that incretin therapies may be safely utilized in patients with psychiatric comorbidities. Specific psychiatric considerations include the possibility of worsening active suicidal ideation as well as impacting certain eating disorder symptomology. Incretin therapies are highly effective medications for management of obesity and overweight. While patients with known psychiatric disorders were often excluded from clinical trials, retrospective data and pilot studies suggest that these agents are effective and largely safe in this patient population.

Article Information

Published Online: September 4, 2025. https://doi.org/10.4088/PCC.25nr03924

© 2025 Physicians Postgraduate Press, Inc.

Submitted: January 21, 2025; accepted May 5, 2025.

To Cite: Elmaoued AA, White RT. Incretin therapies: a new tool to combat metabolic consequences of antipsychotic use. Prim Care Companion CNS Disord 2025;27(5):25nr03924.

Author Affiliations: University of New Mexico College of Pharmacy, Albuquerque, New Mexico (Elmaoued); Taneja College of Pharmacy, University of South Florida, Tampa, Florida (White).

Corresponding Author: Raechel T. White, PharmD, PhC, BCACP, Department of Pharmacotherapeutics and Clinical Research, Taneja College of Pharmacy, University of South Florida, 560 Channelside Dr, Tampa, FL 33602 ([email protected]).

Relevant Financial Relationships: None.

Funding/Support: None.

Clinical Points

- There is a critical need to address cardiometabolic comorbidities in people with psychiatric conditions.

- Incretin therapies have emerged as a promising treatment option with potential benefits for mitigating the cardiometabolic side effects associated with antipsychotic medications; however, clinical trials have frequently excluded psychiatric populations from their studies.

- While preliminary data suggest efficacy of these agents in psychiatric populations, more research is needed to fully assess safety and efficacy.

References (64)

- Pillinger T, McCutcheon RA, Vano L, et al. Comparative effects of 18 antipsychotics on metabolic function in patients with schizophrenia, predictors of metabolic dysregulation, and association with psychopathology: a systematic review and network meta-analysis. Lancet Psychiatry. 2020;7(1):64–77. PubMed CrossRef

- Chwastiak LA, Rosenheck RA, Kazis LE. Association of psychiatric illness and obesity, physical inactivity, and smoking among a national sample of veterans. Psychosomatics. 2011;52(3):230–236. PubMed CrossRef

- Holt RIG, Mitchell AJ. Diabetes mellitus and severe mental illness: mechanisms and clinical implications. Nat Rev Endocrinol. 2015;11(2):79–89. PubMed CrossRef

- Lee MK, Lee SY, Sohn SY, et al. Type 2 diabetes and its association with psychiatric disorders in young adults in South Korea. JAMA Netw Open. 2023;6(6):e2319132. PubMed CrossRef

- Garriga M, Mallorquí A, Bernad S, et al. Antipsychotic-associated weight gain and clinical improvement under clozapine treatment. J Clin Psychopharmacol. 2022;42(1):75–80. PubMed

- Larsen JR, Vedtofte L, Jakobsen MSL, et al. Effect of liraglutide treatment on prediabetes and overweight or obesity in clozapine- or olanzapine-treated patients with schizophrenia spectrum disorder: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA Psychiatry. 2017;74(7):719–728. PubMed CrossRef

- Waite F, Langman A, Mulhall S, et al. The psychological journey of weight gain in psychosis. Psychol Psychother. 2022;95(2):525–540. PubMed CrossRef

- Shen Q, Mikkelsen DH, Luitva LB, et al. Psychiatric disorders and subsequent risk of cardiovascular disease: a longitudinal matched cohort study across three countries. eClinicalMedicine. 2023;61:102063. PubMed CrossRef

- Nielsen RE, Banner J, Jensen SE. Cardiovascular disease in patients with severe mental illness. Nat Rev Cardiol. 2021;18(2):136–145. PubMed CrossRef

- de Silva VA, Suraweera C, Ratnatunga SS, et al. Metformin in prevention and treatment of antipsychotic induced weight gain: a systematic review and meta-analysis. BMC Psychiatry. 2016;16(1):341. PubMed CrossRef

- The American Psychiatric Association. Practice Guideline for the Treatment of Patients With Schizophrenia. Third Edition. American Psychiatric Association; 2020. Accessed April 6, 2023. https://psychiatryonline.org/doi/book/10.1176/books.9780890424841

- Davies MJ, Bergenstal R, Bode B, et al. Efficacy of liraglutide for weight loss among patients with type 2 diabetes: the SCALE diabetes randomized clinical trial. JAMA. 2015;314(7):687–699. PubMed CrossRef

- Garvey WT, Frias JP, Jastreboff AM, et al. Tirzepatide once weekly for the treatment of obesity in people with type 2 diabetes (SURMOUNT-2): a double-blind, randomised, multicentre, placebo-controlled, phase 3 trial. Lancet. 2023;402(10402):613–626. PubMed CrossRef

- Wadden TA, Chao AM, Machineni S, et al. Tirzepatide after intensive lifestyle intervention in adults with overweight or obesity: the SURMOUNT-3 phase 3 trial. Nat Med. 2023;29(11):2909–2918. PubMed CrossRef

- Davies M, Færch L, Jeppesen OK, et al. Semaglutide 24·mg once a week in adults with overweight or obesity, and type 2 diabetes (STEP 2): a randomised, double-blind, double-dummy, placebo-controlled, phase 3 trial. Lancet. 2021;397(10278):971–984. PubMed CrossRef

- Wilding JPH, Batterham RL, Calanna S, et al. Once-weekly semaglutide in adults with overweight or obesity. N Engl J Med. 2021;384(11):989–1002. PubMed CrossRef

- Jastreboff AM, Kaplan LM, Frías JP, et al. Triple–hormone-receptor agonist retatrutide for obesity — a phase 2 trial. N Engl J Med. 2023;389(6):514–526. PubMed CrossRef

- Aronne LJ, Sattar N, Horn DB, et al. Continued treatment with tirzepatide for maintenance of weight reduction in adults with obesity: the SURMOUNT-4 randomized clinical trial. JAMA. 2024;331(1):38–48. PubMed CrossRef

- Jastreboff AM, Aronne LJ, Ahmad NN, et al. Tirzepatide once weekly for the treatment of obesity. N Engl J Med. 2022;387(3):205–216. PubMed CrossRef

- McIntyre RS, Mansur RB, Rosenblat JD, et al. The association between glucagon-like peptide-1 receptor agonists (GLP-1 RAs) and suicidality: reports to the Food and Drug Administration Adverse Event Reporting System (FAERS). Expert Opin Drug Saf. 2024;23(1):47–55. PubMed CrossRef

- Vasiliu O. Therapeutic management of atypical antipsychotic-related metabolic dysfunctions using GLP-1 receptor agonists: a systematic review. Exp Ther Med. 2023;26(1):355. PubMed CrossRef

- Bak M, Campforts B, Domen P, et al. Glucagon-like peptide agonists for weight management in antipsychotic-induced weight gain: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 2024;150(6):516–529. PubMed CrossRef

- Siskind D, Russell A, Gamble C, et al. Metabolic measures 12 months after a randomised controlled trial of treatment of clozapine associated obesity and diabetes with exenatide (CODEX). J Psychiatr Res. 2020;124:9–12. PubMed CrossRef

- Khaity A, Mostafa Al-Dardery N, Albakri K, et al. Glucagon-like peptide-1 receptor-agonists treatment for cardio-metabolic parameters in schizophrenia patients: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Front Psychiatry. 2023;14:1153648. PubMed

- Prasad F, De R, Korann V, et al. Semaglutide for the treatment of antipsychotic-associated weight gain in patients not responding to metformin - a case series. Ther Adv Psychopharmacol. 2023;13:20451253231165169. PubMed CrossRef

- Noda K, Kato T, Nomura N, et al. Semaglutide is effective in type 2 diabetes and obesity with schizophrenia. Diabetol Int. 2022;13(4):693–697. PubMed CrossRef

- Sass MR, Danielsen AA, Köhler-Forsberg O, et al. Effect of the GLP-1 receptor agonist semaglutide on metabolic disturbances in clozapine-treated or olanzapine-treated patients with a schizophrenia spectrum disorder: study protocol of a placebo-controlled, randomised clinical trial (SemaPsychiatry). BMJ Open. 2023;13(1):e068652. PubMed

- Jastreboff AM, le Roux CW, Stefanski A, et al. Tirzepatide for obesity treatment and diabetes prevention. N Engl J Med. 2025;392(10):958–971. PubMed CrossRef

- Sutar R, Kumar A, Yadav V. Suicide and prevalence of mental disorders: a systematic review and meta-analysis of world data on case-control psychological autopsy studies. Psychiatry Res. 2023;329:115492. PubMed CrossRef

- Chen W, Cai P, Zou W, et al. Psychiatric adverse events associated with GLP-1 receptor agonists: a real-world pharmacovigilance study based on the FDA Adverse Event Reporting System database. Front Endocrinol. 2024;15:1330936. PubMed CrossRef

- Hejdak D, Razzak AN, Sun L, et al. Interaction of semaglutide and ziprasidone in a patient with schizophrenia: a case report. Cureus. 2024;16(4):e59319. PubMed CrossRef

- Novo Nordisk. Ozempic (Semaglutide) Injection. Plainsboro; 2017. Accessed April 29, 2025. https://www.accessdata.fda.gov/drugsatfda_docs/label/2017/209637lbl.pdf

- Pfizer Inc. Ziprasidone Hydrochloride Capsules. Pfizer Inc.; 2015. Accessed April 29, 2025. https://www.accessdata.fda.gov/drugsatfda_docs/label/2015/020825s054,020919s041,021483s014lbl.pdf

- Sunovion Pharmaceuticals Inc. Latuda (Lurasidone Hydrochloride) Tablets. Sunovion Pharmaceuticals Inc; 2013. Accessed April 29, 2025. https://www.accessdata.fda.gov/drugsatfda_docs/label/2013/200603lbls10s11.pdf

- Kouidrat Y, Amad A, Lalau JD, et al. Eating disorders in schizophrenia: implications for research and management. Schizophr Res Treat. 2014;2014:791573. PubMed CrossRef

- Fornaro M, Daray FM, Hunter F, et al. The prevalence, odds and predictors of lifespan comorbid eating disorder among people with a primary diagnosis of bipolar disorders, and vice-versa: systematic review and meta-analysis. J Affect Disord. 2021;280(Pt A):409–431. PubMed CrossRef

- Ronveaux CC, Tomé D, Raybould HE. Glucagon-like peptide 1 interacts with ghrelin and leptin to regulate glucose metabolism and food intake through vagal afferent neuron signaling. J Nutr. 2015;145(4):672–680. PubMed CrossRef

- Balantekin KN, Kretz MJ, Mietlicki-Baase EG. The emerging role of glucagon-like peptide-1 in binge eating. J Endocrinol. 2024;262(1):e230405. PubMed CrossRef

- Innocent B, Elmaoued AA, Cowart K, et al. Dulaglutide use to improve binge eating behaviors in a person with type 2 diabetes and obesity. Am J Health Syst Pharm. 2025;12:zxaf088.

- American Diabetes Association Professional Practice Committee. 9. Pharmacologic approaches to glycemic treatment: standards of care in diabetes- 2025. Diabetes Care. 2025;48(Suppl 1):S181–S206. PubMed CrossRef

- McGuire DK, Marx N, Mulvagh SL, et al. Oral semaglutide and cardiovascular outcomes in high-risk type 2 diabetes. N Engl J Med. 2025;392(20):2001–2012. PubMed CrossRef

- Perkovic V, Tuttle KR, Rossing P, et al. Effects of semaglutide on chronic kidney disease in patients with type 2 diabetes. N Engl J Med. 2024;391(2):109–121. PubMed CrossRef

- Lincoff AM, Brown-Frandsen K, Colhoun HM, et al. Semaglutide and cardiovascular outcomes in obesity without diabetes. N Engl J Med. 2023;389(24):2221–2232. PubMed CrossRef

- Packer M, Zile MR, Kramer CM, et al. Tirzepatide for heart failure with preserved ejection fraction and obesity. N Engl J Med. 2025;392(5):427–437. PubMed CrossRef

- Kosiborod MN, Abildstrøm SZ, Borlaug BA, et al. Semaglutide in patients with heart failure with preserved ejection fraction and obesity. N Engl J Med. 2023;389(12):1069–1084. PubMed CrossRef

- Kosiborod MN, Petrie MC, Borlaug BA, et al. Semaglutide in patients with obesity-related heart failure and type 2 diabetes. N Engl J Med. 2024;390(15):1394–1407. PubMed CrossRef

- American Diabetes Association. 9. Pharmacologic approaches to glycemic treatment: standards of medical care in diabetes—2021. Diabetes Care. 2021;44(Suppl 1):S111–S124. Accessed November 18, 2021. https://care.org/content/44/Supplement_1/S111

- Eli Lilly and Company. A randomized, double-blind, phase 3 study to investigate the efficacy and safety of LY3437943 once weekly compared to placebo in participants with severe obesity and established cardiovascular disease. ClinicalTrials.gov. 2024. Accessed April 29, 2025. https://clinicaltrials.gov/study/NCT05882045

- Eli Lilly and Company. A study of retatrutide (LY3437943) in participants who have obesity or overweight with weight-related comorbidities (TRIUMPH-3). ClinicalTrials.gov. 2024. Accessed April 29, 2025. https://clinicaltrials.gov/study/NCT05929079

- Bradley T, Campbell E, Dray J, et al. Systematic review of lifestyle interventions to improve weight, physical activity and diet among people with a mental health condition. Syst Rev. 2022;11(1):198. PubMed CrossRef

- American Diabetes Association Professional Practice Committee. 5. Facilitating positive health behaviors and well-being to improve health outcomes: standards of care in diabetes-2025. Diabetes Care. 2025;48(Suppl 1):S86–S127. PubMed CrossRef

- Jensen SBK, Blond MB, Sandsdal RM, et al. Healthy weight loss maintenance with exercise, GLP-1 receptor agonist, or both combined followed by one year without treatment: a post-treatment analysis of a randomised placebo-controlled trial. eClinical Medicine. 2024;69:102475. PubMed CrossRef

- Wilding JPH, Batterham RL, Davies M, et al. Weight regain and cardiometabolic effects after withdrawal of semaglutide: the STEP 1 trial extension. Diabetes Obes Metab. 2022;24(8):1553–1564. PubMed CrossRef

- Bray GA, Kim KK, Wilding JPH, et al. Obesity: a chronic relapsing progressive disease process. A position statement of the World Obesity Federation. Obes Rev. 2017;18(7):715–723. PubMed CrossRef

- Novo Nordisk. Victoza (Liraglutide) Injection. U.S. Food and Drug Administration; 2015. Accessed April 29, 2025. https://www.accessdata.fda.gov/drugsatfda_docs/label/2015/022341s020lbl.pdf

- Novo Nordisk. Saxenda (Liraglutide) Injection. U.S. Food and Drug Administration; 2015. Accessed April 29, 2025. https://www.accessdata.fda.gov/drugsatfda_docs/label/2015/206321lbl.pdf

- Novo Nordisk. Wegovy (Semaglutide) Injection. U.S. Food and Drug Administration; 2023. Accessed April 29, 2025. https://www.accessdata.fda.gov/drugsatfda_docs/label/2023/215256s007lbl.pdf

- Novo Nordisk. Rybelsus (Semaglutide) Tablets. U.S. Food and Drug Administration; 2024. Accessed April 29, 2025. https://www.accessdata.fda.gov/drugsatfda_docs/label/2024/213051s018lbl.pdf

- Eli Lilly and Company. Trulicity (Dulaglutide) Injection. Eli Lilly and Company; 2020. Accessed April 29, 2025. https://www.accessdata.fda.gov/drugsatfda_docs/label/2020/125469s036lbl.pdf

- Eli Lilly and Company. Byetta (Exenatide) Injection. Eli Lilly and Company; 2020. Accessed April 29, 2025. https://www.accessdata.fda.gov/drugsatfda_docs/label/2020/021773s043lbl.pdf

- Amylin Pharmaceuticals. Bydureon (Exenatide Extended Release) Injection. Amylin Pharmaceuticals; 2021. Accessed April 29, 2025. https://www.accessdata.gov/drugsatfda_docs/label/2021/021973s017lbl.pdf

- Eli Lilly and Company. Mounjaro (Tirzepatide) Injection. Eli Lilly and Company; 2022. Accessed April 29, 2025. https://www.accessdata.fda.gov/drugsatfda_docs/label/2022/215866s000lbl.pd

- Eli Lilly and Company. Zepbound (Tirzepatide) Injection. Eli Lilly and Company; 2024. Accessed April 29, 2025. https://www.accessdata.fda.gov/drugsatfda_docs/label/2024/217806s013lbl.pdf

- Jastreboff AM, Kaplan LM, Frías JP, et al. Triple–hormone-receptor agonist retatrutide for obesity - a phase 2 trial. N Engl J Med. 2023;389(6):514–526. PubMed CrossRef

Enjoy this premium PDF as part of your membership benefits!