Misuse of nonpsychoactive medications—like corticosteroids, hormones, and appetite stimulants—for cosmetic purposes is frequently observed in clinical practice.1 Though lacking psychoactive properties, these agents are often repurposed to achieve culturally valued body ideals, especially where larger body size is associated with health and prosperity and thinness is stigmatized.2

A content analysis of 843 YouTube videos, identified using predefined keywords between February 20 and March 4, 2023, found nearly 70% promoted corticosteroid misuse, most frequently dexamethasone, with common procurement sources.3 In India, reports of corticosteroid and cyproheptadine misuse are emerging, with usage driven by peer influence and gym culture. Documented harms include dependence, withdrawal symptoms, and metabolic complications.4

Dexamethasone and cyproheptadine, both appetite stimulating, are widely marketed and often used without medical supervision for weight gain. Despite the risk of serious metabolic and endocrine complications, they continue to be misused for their cosmetic appeal.5,6

Despite rising concern, such misuse often escapes clinical attention due to the absence of intoxication or overt psychiatric symptoms. This report describes a case of unsupervised dexamethasone and cyproheptadine use spanning 2 decades without treatment. It highlights how normalization of “nonaddictive” medications and appearance-based ideals can delay recognition, creating a diagnostic blind spot.

Case Report

Mr A, a 38-year-old unmarried man with an easy temperament and family history of opioid dependence, was referred to our center after presenting to his physician with an axillary abscess, during which he was diagnosed with steroid-induced diabetes. His physician advised treatment for steroid misuse, and he was subsequently brought to our outpatient department by his brother, who was undergoing treatment for opioid dependence at our center. Mr A reported a 22-year history of dexamethasone and cyproheptadine use. He began using dexamethasone (0.5 mg) and cyproheptadine (4 mg) at age 16 years to gain weight and muscle mass after bullying by peers. The rapid gains, especially in arms, chest, and thighs, boosted self-esteem and reinforced use.

After cessation attempts, rapid weight loss and limb thinning prompted dose escalation to 20 tablets/d. He developed exogenous Cushing syndrome and type 2 diabetes, which was managed with metformin. Despite medical advice, Mr A could not maintain abstinence due to withdrawal symptoms (fatigue, dizziness, appetite loss, nausea). Neither Mr A nor his family, despite a sibling in addiction treatment, viewed this as addiction. No psychiatric comorbidity (body dysmorphic disorder, obsessive-compulsive traits, feeding or elimination disorders) was found, and use was driven by appearance and social reinforcement.

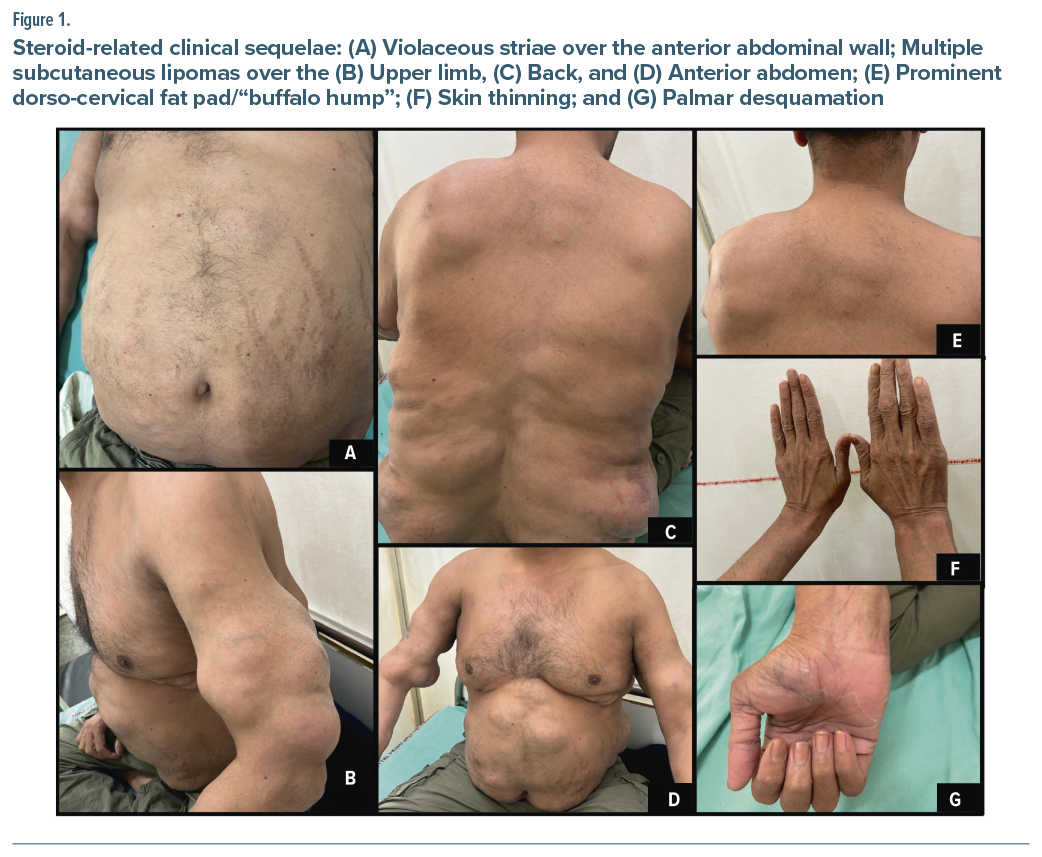

He was overweight (body mass index=28.6 kg/m2) with classical Cushingoid features, including truncal obesity, facial puffiness, proximal muscle wasting, and subcutaneous lipomas limiting limb movement. Additional findings included hyperpigmented striae, tissue paper–thin skin with ecchymoses, and widespread pruritic scaling. Neurologically, he had reduced proximal but preserved distal muscle strength (Figure 1).

He met International Classification of Diseases, Eleventh Revision criteria for harmful pattern of nonpsychoactive substance use. Laboaratory tests confirmed Cushing syndrome, high-risk adrenal insufficiency, and diabetes. Endocrinology, dermatology, and neurology consultations were taken.

Due to the risk of adrenal crisis, he was initiated on prednisolone 5 mg/d. After initial stabilization, this was transitioned to physiologic replacement with hydrocortisone (10 mg in the morning and 5 mg in the evening), with emergency hydrocortisone injections advised for stress or fever. This regimen was continued for 6 weeks. Following cessation, repeat testing confirmed hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal (HPA) axis recovery, and steroid replacement was discontinued. Glycemic control was maintained with metformin 1,000 mg/d; vitamin D and B12 supplements were added. Dermatological issues were treated with antifungals, antihistamines, and mouth paint. Steroid-induced myopathy was managed with strength training and nutritional support post HPA axis stabilization. Irritability and sleep issues were managed initially with benzodiazepines and later switched to mirtazapine. Psychoeducation focused on illness insight and recovery expectations.

After the inpatient stabilization for 21 days, he was discharged on hydrocortisone for 4 weeks with planned follow-up. At 6-week follow-up, HPA axis recovery was confirmed, and steroid replacement was terminated. Over 3 months, he maintained abstinence, resumed work, and reported improved health, with insight into irreversible physical changes.

Discussion

This case provides rare insight into the complications and delayed recognition associated with long-term, nonpsychoactive substance misuse, despite overt harm and a familial history of addiction treatment. Chronic corticosteroid misuse is associated with Cushing syndrome, diabetes, myopathy, and dermatological changes, as well as avascular necrosis, cardiovascular events, psychiatric symptoms, and infections, particularly with long-term high-dose exposure.7 Even nonoral routes can cause toxicity, including Cushingoid features and HPA axis suppression, as reported with intranasal dexamethasone.8

Similar patterns have been reported, including a case series linked to gym culture and over-the-counter access and another involving shorter use duration with milder outcomes.4,9 In contrast, our patient’s misuse spanned over 2 decades and culminated in severe multisystem complications that required prolonged inpatient care. Trends like Kinshasa “C4 phenomenon” highlight rising appearance-driven cyproheptadine misuse.10 Though reports are emerging from Asia and Africa, the cosmetic misuse of pharmacologic agents may represent a broader global issue that remains underrecognized.

This case underscores both the physiologic harms of long-term corticosteroid and antihistamine misuse and the psychosocial dynamics—such as appearance-based reinforcement and familial normalization—that sustain it. Clinicians should maintain a high index of suspicion in patients presenting with Cushingoid features not explained by endocrine or psychiatric conditions. Effective management requires interdepartmental coordination to address complex medical and behavioral needs.

This case highlights important regulatory and public health concerns. Dexamethasone and cyproheptadine were used unsupervised for decades despite visible complications and a family history of addiction. Their cosmetic appeal and perceived safety contributed to delayed recognition and care. In settings where weight gain is culturally valued, such misuse may go unnoticed. Stronger regulation of over-the-counter sales, targeted public awareness on appearance-driven misuse, and heightened clinical suspicion for nontraditional substance use are urgently needed.

Conclusion

Long-term misuse of nonpsychoactive medications like dexamethasone and cyproheptadine may go unrecognized due to their cosmetic appeal and perceived safety. This case highlights how sociocultural reinforcement and family normalization can delay treatment—even in addiction-aware households—underscoring the need for broader clinical suspicion and inclusive addiction frameworks.

Article Information

Published Online: September 25, 2025. https://doi.org/10.4088/PCC.25cr04008

© 2025 Physicians Postgraduate Press, Inc.

Prim Care Companion CNS Disord 2025;27(5):25cr04008

Submitted: May 21, 2025; accepted June 17, 2025.

To Cite: Kaur G, Patel V, Mandal P, et al. Long-term nonprescription use of dexamethasone and cyproheptadine with metabolic and endocrine sequelae. Prim Care Companion CNS Disord 2025;27(5): 25cr04008.

Author Affiliations: National Drug Dependence Treatment Centre, All India Institute of Medical Sciences, New Delhi, India (Kaur, Patel, Mandal, Agrawal, Dayal, Ambekar); Department of Psychiatry, All India Institute of Medical Sciences, Tatibandh, Raipur, India; All India Institute of Medical Sciences, New Delhi, India (Patel).

Corresponding Author: Vinit Patel, DM, Department of Psychiatry, All India Institute of Medical Sciences, 2nd Floor, New Administrative Block, GE Rd, Tatibandh, Raipur 492099, India ([email protected]).

Relevant Financial Relationships: None.

Funding/Support: None.

Patient Consent: Written informed consent was obtained from the patient to publish the case report and accompanying clinical images. Information has been de-identified to protect patient confidentiality.

ORCID: Vinit Patel: https://orcid.org/0000-0001-7171-3225

References (10)

- Cooper RJ. Over-the-counter medicine abuse – a review of the literature. J Subst Use. 2013;18(2):82–107. PubMed CrossRef

- Renzaho AMN. Fat, rich and beautiful: changing socio-cultural paradigms associated with obesity risk, nutritional status and refugee children from sub-Saharan Africa. Health Place. 2004;10(1):105–113. PubMed CrossRef

- Amghar H, El Hani M, Cherrah Y, et al. Incitement to misuse of corticosteroids by Arab YouTubers in a local context. Int J Risk Saf Med. 2024;35(3):233–245. PubMed CrossRef

- Mukherjee A, Das R, Kumar M, et al. Combined cyproheptadine and dexamethasone dependence: is it rare or underreported? A case series. Prim Care Companion CNS Disord. 2024;26(6):24cr03731. PubMed CrossRef

- Johnson DB, Lopez MJ, Kelley B. Dexamethasone. In: StatPearls [Internet]. StatPearls Publishing; 2025. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK482130/

- Lavenstein AF, Dacaney EP, Lasagna L, et al. Effect of cyproheptadine on asthmatic children: study of appetite, weight gain, and linear growth. JAMA. 1962;180(11):912–916. PubMed CrossRef

- Koshi EJ, Young K, Mostales JC, et al. Complications of corticosteroid therapy: a comprehensive literature review. J Pharm Technol. 2022;38(6):360–367. PubMed CrossRef

- Sastre J, Díez JJ, Guzmán AL, et al. Self-induced Cushing’s syndrome due to dexamethasone abuse in nasal spray: clinical and biochemical study. PubMed. 1994;11(4):181–184.

- Karia S, Dave N, Sousa AD, et al. Cyproheptadine and dexamethasone abuse. Natl J Med Res. 2013;3(1):88–89.

- Lulebo AM, Bavuidibo CD, Mafuta EM, et al. The misuse of cyproheptadine: a non-communicable disease risk behaviour in Kinshasa population, Democratic Republic of Congo. Subst Abuse Treat Prev Pol. 2016;11:7. PubMed CrossRef

Enjoy this premium PDF as part of your membership benefits!