Multiple system atrophy (MSA) is a progressive, adult-onset neurodegenerative disorder that typically presents with parkinsonism, cerebellar, and autonomic dysfunction. Its prevalence is 1.9–4.9 cases per 100,000 people.1 Around 20% of patients will manifest with psychiatric symptoms, including delusions and hallucinations.2 It has 2 types: MSA-P (parkinsonian type), resembling Parkinson disease with stiffness, tremors, and balance issues, and MSA-C (cerebellar type), causing ataxia, speech difficulties, and eye movement abnormalities. We discuss the case of a patient presenting with altered mental status, hallucinations, and hyperalgesia of the bilateral lower legs, eventually diagnosed with MSA-C. We demonstrate the need for psychiatrists to be aware of this disorder and explore the role of neuroimaging when assessing atypical psychiatric symptoms.

Case Report

Ms S, a 67-year-old black woman with a history of type 2 diabetes, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, obstructive sleep apnea, and major depressive disorder, presented with suicidal ideation and lower extremity weakness. Her laboratory tests, including computed tomography of the head, were unremarkable except for being positive for COVID-19. Her examination revealed no acute neurologic deficit, but she was noted to demonstrate inattention, disorientation, and fluctuating mental status consistent with delirium. However, electroencephalogram showed no abnormalities. She did not have significant parkinsonian features, nor autonomic dysregulation, and coordination evaluation was limited given inability to follow commands.

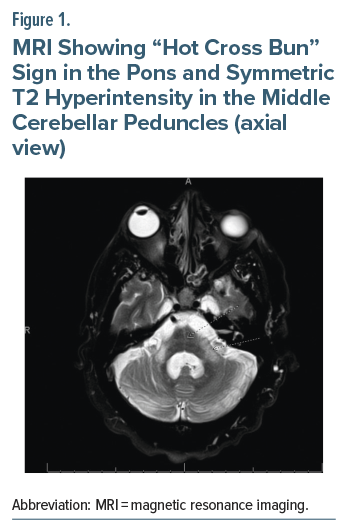

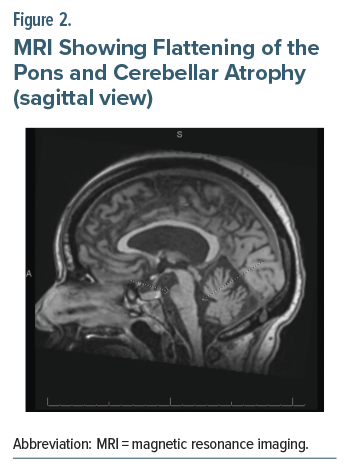

She began experiencing delusions and inattention on day 3. Then, she developed constant auditory and visual hallucinations of a woman named “Carly” in her room on the fifth day of her admission. She had never experienced psychotic symptoms before. Haloperidol was initiated at this time and titrated to 3 mg daily. After not responding, she was switched the next day to risperidone 2 mg instead, with no response for these psychotic symptoms or improvement in her mental status after 2 days of therapy. A week after admission, she was noted to have hyperalgesia of her lower extremities and absent lower extremity reflexes. A broad workup was pursued including lumbar puncture, which was unremarkable, and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI). The MRI showed a “hot cross bun” sign in the pons and symmetric T2 hyperintensity in the middle cerebellar peduncles (axial view, Figure 1) and flattening of the pons and cerebellar atrophy (sagittal view, Figure 2), consistent with MSA-C.

Discussion

The cerebellum is important in regulation of affect, and lesions affecting it can cause a variety of psychiatric symptoms, from emotional dysregulation to psychosis.3 Our patient’s symptoms of depression, suicidal ideation, and hallucinations could be due to cerebellar dysfunction caused by her then undiagnosed MSA-C. Neurotransmitter dysfunction, oxidative stress, and neurotrophic factors are considered common denominators between MSA and depression pathology.4 Hallucinations because of brain stem damage can result in so-called “peduncular hallucinosis,” characterized by complex vivid auditory and visual hallucinations, often of intimate family members in the context of new-onset lesions to the midbrain, pons, or thalamus,5 consistent with Ms S’s symptoms.

Our case expands on a limited number of reports with psychosis as the presenting symptom of MSA-C.6 Typically, patients with MSA-C present with parkinsonism, ataxia, autonomic dysfunction, tremors, dysphonia, abnormal posturing, and rapid eye movement sleep behavior disorder.1 Thus, psychiatrists should be familiar with MSA-C as a potential cause of altered mental status and psychosis. Timely diagnosis, and thus more effective management, leads to better quality of life for patients.1 It is especially important given that patients with MSA-C who develop psychiatric symptoms have a poorer prognosis.2 Our patient had several other hospitalizations within the next 3 months for delirium due to urinary tract infections and other electrolyte derangements. Review of outpatient neurology notes showed that Ms S has been taking citalopram, started around 4 months after discharge, which she has been tolerating well with no reported mood or psychotic symptoms. Our case is also consistent with other reports in which antipsychotic treatment was not effective in psychiatric symptom control in MSA-C, and it is generally avoided as it can worsen parkinsonism,7 though the latter did not occur.

Most patients with MSA-C will have imaging signs within 2 years of symptom onset,8 with an average age of onset at 56 years,1 so it is essential that imaging be pursued even if recent studies have been unremarkable. The preferred imaging modality for MSA-C is MRI.9 Ms S had a normal MRI about a month prior, and a normal head computed tomography scan on arrival, highlighting the rapidly progressive nature of her illness.

Conclusion

Psychiatrists should be familiar with MSA-C as a potential cause of patients presenting acutely with psychiatric symptoms. Antipsychotic treatment is generally avoided in these patients due to lack of efficacy and side effects. In cases of altered mental status in older patients with acute-onset psychiatric symptoms and neurological signs not responding to antipsychotics, a head MRI is warranted as part of a broad workup even with recent imaging, as secondary causes may be otherwise missed.

Article Information

Published Online: November 20, 2025. https://doi.org/10.4088/PCC.25cr04005

© 2025 Physicians Postgraduate Press, Inc.

Prim Care Companion CNS Disord 2025;27(6):25cr04005

Submitted: May 17, 2025; accepted August 5, 2025.

To Cite: Milanak S, Shah K, Bhatti J, et al. Multiple system atrophy presenting as late-onset psychosis. Prim Care Companion CNS Disord 2025;27(6):25cr04005.

Author Affiliations: Wake Forest University School of Medicine, Winston-Salem, North Carolina (all authors).

Corresponding Author: Spencer Milanak, BA, Wake Forest University School of Medicine, Winston-Salem, North Carolina ([email protected]).

Relevant Financial Relationships: None.

Funding/Support: None.

Patient Consent: Consent was received from the patient to publish the case report, and information has been de-identified to protect anonymity.

References (9)

- Goh YY, Saunders E, Pavey S, et al. Multiple system atrophy. Pract Neurol. 2023;23(3):208–221. PubMed CrossRef

- Palma JA, Martinez J, Norcliffe-Kaufmann L, et al. Psychosis in multiple system atrophy. Neurol Journals. 2018. 90(15)(suppl)

- Schmahmann JD, Weilburg JB, Sherman JC. The neuropsychiatry of the cerebellum -insights from the clinic. Cerebellum. 2007;6(3):254–267. PubMed CrossRef

- Lv Q, Pan Y, Chen X, et al. Depression in multiple system atrophy: views on pathological, clinical and imaging aspects. Front Psychiatry. 2022;13:980371. PubMed CrossRef

- Couse M, Wojtanowicz T, Comeau S, et al. Peduncular hallucinosis associated with a pontine cavernoma. Ment Illn. 2018;10(1):7586. PubMed CrossRef

- D’Souza GL, Nayak P. Rare presentation of hallucinations in cerebellar multisystem atrophy. Int J Res Med Sci. 2021;9(1):285–286.

- Yawata T, Takagi S, Tamura T, et al. Psychosis treatment in a patient with parkinsonian type multiple system atrophy using modified electroconvulsive therapy: a case report, Psychogeriatrics, 2023;23(2):364-367. PubMed CrossRef

- Watanabe H, Riku Y, Hara K, et al. Clinical and imaging features of multiple system atrophy: challenges for an early and clinically definitive diagnosis. J Mov Disord. 2018;11(3):107–120. PubMed CrossRef

- Kim HJ, Jeon B, Fung VSC. Role of magnetic resonance imaging in the diagnosis of multiple system atrophy. Mov Disord Clin Pract. 2017;4(1):12–20. PubMed CrossRef

Enjoy this premium PDF as part of your membership benefits!