Lessons Learned at the Interface of Medicine and Psychiatry

The Psychiatric Consultation Service at Massachusetts General Hospital sees medical and surgical inpatients with comorbid psychiatric symptoms and conditions. During their twice-weekly rounds, Dr Stern and other members of the Consultation Service discuss diagnosis and management of hospitalized patients with complex medical or surgical problems who also demonstrate psychiatric symptoms or conditions. These discussions have given rise to rounds reports that will prove useful for clinicians practicing at the interface of medicine and psychiatry.

Prim Care Companion CNS Disord 2026;28(1):25f04061

Author affiliations are listed at the end of this article.

Have you wondered whether your stress levels are rising and felt concerned that you were burning out? Have you been uncertain if you have major depression and whether you should be evaluated and treated by a mental health professional? Have you thought about what you might do to reduce your stress and whether your health care system could, or should, do something so that you enjoy your medical practice again? If you have, the following case vignette and discussion should prove useful.

Physician burnout is now a widespread concern.1 Yet, the distinction between depression and burnout remains poorly understood, which can lead to a misunderstanding of emotions or missed opportunities for systemic solutions. Here, we clarify misconceptions about burnout and depression and identify best practices and approaches for burnout at the individual and institutional levels.

CASE VIGNETTE

Dr A, a primary care physician who has worked in the same academic hospital–affiliated group practice for the past 16 years (since she graduated from residency), has a panel of 2,500 patients, the majority of whom have multiple complex medical problems. During the COVID-19 pandemic, more than 30 of her patients died. She felt grief about losing so many of her long-term patients.

However, over the past year, Dr A’s sadness turned into anger and irritability. Initially, her emotions were related to shortcomings in the medical system, but slowly, they extended toward her leaders, colleagues, and patients. Dr A felt distressed when she realized she was being less empathic with patients. She had a tough time sleeping at night and felt exhausted during the daytime. She experienced less enjoyment from her work and dreaded going to her office. Dr A also noticed afternoon headaches, which interfered with her ability to focus on her patients’ problems. Among family and friends, Dr A was irritable and edgy. She often thought about leaving her role in the group practice and medicine altogether but was not sure how she could support her family financially. She felt trapped, hopeless, and lost.

DISCUSSION

Is Burnout Synonymous With Depression?

When the stress of practicing medicine exceeds a clinician’s capacity for resilience (ie, the adaptive capacity to respond to stress and withstand adversity), burnout can arise. Burnout is characterized by emotional exhaustion (loss of enthusiasm), depersonalization (lack of empathy for, or negative attitudes toward, patients), and reduced personal accomplishment leading to maladaptive behaviors (including cynicism, hostility, and detachment). Burnout decreases professionalism and access to and the quality of care delivered, increases the risk of medical errors and the cost of care, and contributes to early retirement.1 Due to job-related demands and stressors, clinicians (in all specialties and practice settings) are experiencing disproportionately higher levels of burnout.2–4 Recent data show that approximately 45%–60% of physicians experience at least 1 symptom of burnout.1,4 Rates are similarly elevated among nurses as well as those practicing in other clinical disciplines.1,4

Despite overlapping symptoms of burnout and depression, burnout is not synonymous with depression (or with major depressive disorder), although low mood can herald burnout. Distinguishing between the two is crucial, since these conditions require different treatment approaches. Key differences include that burnout is not a clinical syndrome.5 Instead, it is an “occupational phenomenon” linked to chronic work stress.6 On the other hand, depression is a mental health disorder with a different cluster of core somatic and psychological symptoms that form the basis of its diagnostic criteria. Depression requires at least 2 weeks of pervasive low mood or anhedonia and 4 or more of the following: disruption of sleep, disturbed appetite, a decrease in energy, impaired concentration ability, increased or decreased psychomotor activity, or hopelessness/ suicidal thoughts with significant impairment across all of life domains. Depression is also driven by more than occupational causes.7

Symptoms of both burnout and depression include emotional distress, as well as changes in mood, energy, focus, concentration, and motivation; these manifestations lead to functional impairment. However, burnout’s primary characteristics (eg, emotional exhaustion, depersonalization, and a reduced personal sense of accomplishment at work) do not typically include pervasive mood changes.8

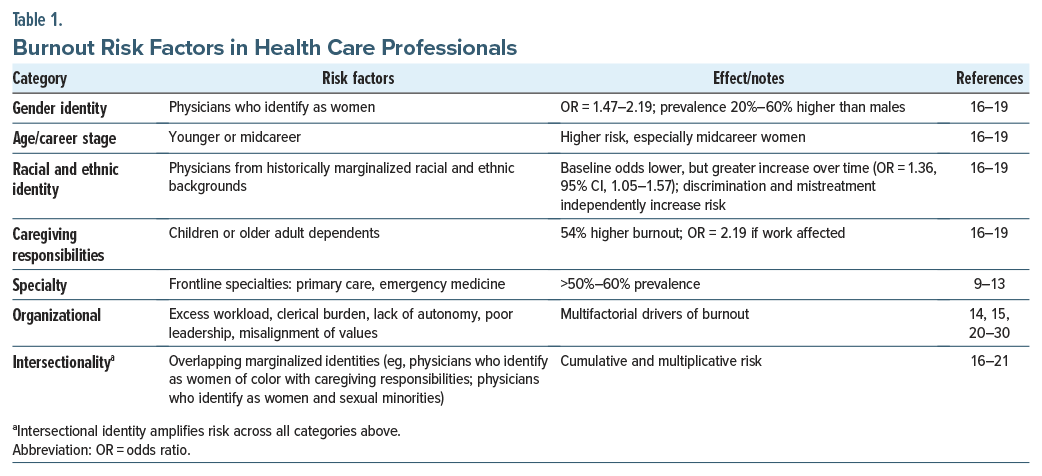

Which Physicians Are at Risk for Burnout (and How Common Is It)?

Even before the COVID-19 pandemic, burnout among attending physicians in the United States was already at concerning levels. Nationally representative surveys using the Maslach Burnout Inventory (MBI) found that the prevalence of at least 1 symptom of burnout among US physicians was 45.5% in 2011, 54.4% in 2014, and 43.9% in 2017.9 These rates were consistently higher than those observed in the general US working population, with physicians reporting a 1.4-fold increased risk for burnout compared to other workers in 2020.10 Burnout rates varied substantially by specialty, with the highest rates found in frontline specialties. For instance, practitioners in emergency medicine, primary care (family medicine, general internal medicine), and neurology reported the highest rates, often exceeding 50%–60%. In contrast, those in dermatology, pathology, and ophthalmology reported lower rates, typically below 40%.

The COVID-19 pandemic changed the physician well-being landscape to raise levels of burnout. Rates of burnout peaked at 62.8% in late 2021—the highest level ever recorded in national surveys.11 This major increase in burnout rates occurred across nearly all specialties but was most prominent in primary care, emergency medicine, and critical care, where rates often exceeded 60%.12

At the end of the US public health emergency (2023–2024), there was a partial but incomplete recovery of burnout among physicians. The most recent national survey found that 45.2% of US physicians reported at least 1 symptom of burnout in 2023, a significant improvement from the 62.8% peak in 2021 (P < .001), but like those of prepandemic levels in 2011 and 2017.11 Despite this recovery, physicians continue to have a higher risk of burnout than other US workers, with an odds ratio (OR) of 1.82 (95% CI, 1.63–2.05) in 2023.11 Internationally, one meta-analysis of 45 studies found a pooled burnout prevalence of 54.6% among physicians during the pandemic, with the highest rates in the Middle East and North Africa (66.6%), followed by Europe (48.8%) and South America (42%).13

Drivers of physician burnout are multifactorial (eg, excessive workload and time pressure, lack of control and autonomy, administrative and clerical burden, work-home conflict and poor work-life integration, and negative organizational culture and leadership).14,15 Structural and demographic factors (including identifying as a woman, younger age, midcareer stage, caregiving responsibilities, and membership in historically marginalized racial or ethnic groups) further influence vulnerability to burnout.16–19 For example, female physicians are at significantly higher risk, with ORs ranging from 1.47 (95% CI, 1.02–2.12) to 2.19 (95% CI, 1.51–3.17) compared to men, and prevalence estimates 20%–60% higher than that of men. The gender gap is notably pronounced among midcareer physicians and those with caregiving responsibilities. Physicians from historically marginalized racial and ethnic backgrounds have generally reported lower odds of burnout at baseline, but their increase in burnout over time has been more pronounced (OR = 1.36; 95% CI, 1.05–1.57). Experiences of discrimination and mistreatment are independently associated with higher burnout risk, especially among physicians who identify as women or as having a disability or who are underrepresented in medicine. Caregiving responsibilities, particularly for children or older adult family members, increase burnout risk by 54%, and clinicians whose caregiving responsibilities impact their work have more than double the odds of reporting burnout (OR = 2.19; 95% CI, 1.54–3.11).16–19

Intersectional factors, such as identifying as a woman of color in a high-intensity specialty with significant caregiving responsibilities, confer the highest cumulative risk for burnout.19–21 Burnout among female physicians from historically marginalized racial and ethnic backgrounds increased from 37.2% in 2018 to 45.8% in 2022.20 Moreover, female medical students who identify as sexual minorities had an 8-fold higher predicted probability of burnout compared with those identifying as heterosexual.21

Why Does Burnout Develop?

The Stanford Model of Occupational Well-Being offers a framework for the factors that lead to physician burnout (eg, workplace efficiency [referring to structures, systems, processes, practices, and policies that optimize efficiency and efficacy related to the delivery of high-quality clinical care and relationships among patients and physicians], work culture, and individual factors).22 Components of workplace efficiency that contribute to burnout in health care settings include inefficient communication among teams, inadequate staffing for clinical care, absence of physicians’ voices when redesigning roles and workflows that improve processes or facilitate task-shifting, excessive requirements for electronic health record (EHR) documentation, ever-expanding management of inboxes and administrative tasks, and inadequate coverage for time off from work.15,22,23

Inadequate advocacy for physicians’ needs and for realistic work schedules, absence of role-modeling for self-compassion, and a lack of control and flexibility each exacerbate burnout.24–26 Organizational cultures that are permeated by an inadequate appreciation for physicians’ time and skills also contribute to burnout.27 This effect is intensified by a lack of transparency, fairness, and protection from mistreatment by patients or colleagues.28 Individual factors (eg, stigma toward mental health care, a lack of accessible resources and support) drive burnout.22–24 Night call and sleep deprivation also provide fertile ground for the development of burnout in medical trainees and faculty.15,22,23

Misalignment of values (between physicians and health care organizations) also precipitates burnout.29,30 For instance, physicians may experience role reduction (eg, being thought of as “employees,” rather than as respected professionals) in systems that prioritize the “bottom line” over compassionate clinical care.30 In some academic medical centers, the pressure to publish and be promoted also competes with an individual’s clinical mission.31 Physicians may perceive that their academic institution values research productivity over clinical care, which invalidates and diminishes the meaning of one’s work.30,31 The stressors associated with the practice of medicine (including delayed gratification, caregiver burden, patient dissatisfaction, and malpractice litigation) can be unbearable if they intersect with values misalignment—overwhelming the physician’s physical and emotional capacity to meet their professional oath.29

Finally, with sweeping changes in the sociopolitical landscape, political uncertainty, public mistrust of science, and inequities have profoundly impacted both patients and practitioners. These factors can amplify moral distress and contribute to burnout among physicians.31,32

Table 1 provides burnout risk factors for health professionals.

How Can Health Care Organizations Identify and Prevent Burnout?

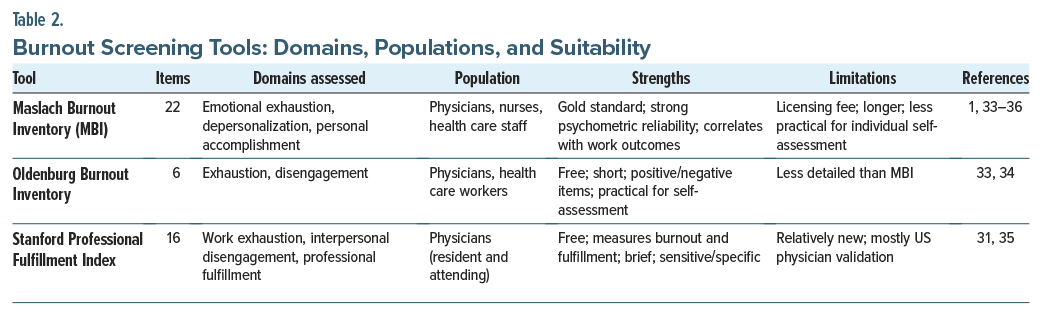

Health care organizations can help their at-risk staff by using empirically supported screening tools to help diagnose burnout and distinguish it from depression. These tools may focus on screening for manifestations of burnout or on searching for areas of professional fulfillment. For instance, the MBI, considered the “gold standard” for assessment of burnout, is a 22-item survey that covers emotional exhaustion, depersonalization, and low sense of personal accomplishment.33 Extensive data validate results of the MBI and health care–related outcomes (eg, medical errors, malpractice claims, and physician turnover), as well as personal outcomes (eg, alcohol use, thoughts of suicide, and motor vehicle accidents).33,34

Another tool, the Oldenburg Burnout Inventory, is a 6-item survey that covers exhaustion (physical, cognitive, and affective aspects) and disengagement from work (negative attitudes toward work objects, work content, or work in general). The Oldenburg Burnout Inventory assesses both positively and negatively framed items, and it was developed in response to the MBI’s lacking the latter.33 Additionally, the Stanford Professional Fulfillment Index (PFI) is a 16-item survey that covers burnout (work exhaustion and interpersonal disengagement) and professional fulfillment. The PFI was specifically developed to assess physician burnout, and compared to the MBI, it has a sensitivity and specificity of 72% and 84%, respectively.31,34 Data indicate that each of these tools has consistent psychometric performance across demographic groups, including gender and age.33–36 Given that most items focus on work-related experiences, there is limited evidence that education level or socioeconomic background significantly affects measurement validity.36

Each of these instruments offers specific advantages. For instance, the MBI, with strong psychometric reliability and correlation with work-related outcomes, is suited for organizational assessments or research. However, with a licensing fee, the MBI is less practical for individual clinicians seeking rapid self-assessment.33,34 The Oldenburg Burnout Inventory is free and shorter and offers both positively and negatively worded items, making it manageable for busy physicians seeking self-assessment.33 The PFI is brief, free, and accessible, offering value both for self-assessment and to health care organizations or departments monitoring clinician well-being over time.35

Screening, whether self-initiated or by an organization, is only a first step in the assessment of burnout. Structured follow-up and access to resources should follow positive screening.6–8,33 For instance, a positive screen for burnout does not exclude depression. Instead, it should prompt further screening for co-occurring depression through a validated tool such as the Patient Health Questionnaire-9.6–8,37 When depression has been excluded, individuals with burnout should be offered targeted interventions (such as coaching, mindfulness, or organizational support) and monitored over time. For physicians who have persistent depressive symptoms, suicidal ideation, or significant functional impairment, referral to mental health treatment should be arranged. By distinguishing burnout from depression and identifying next steps, organizations can provide timely support to promote well-being.6–8,15,33–36

In addition, cultivating self-awareness and leadership awareness on burnout is critical to identify and prevent burnout. For instance, warning signs of burnout may be related to an individual’s appearance (eg, is the physician fatigued?), performance (eg, is the physician’s work effort declining?), tension (eg, is the physician bored or overwhelmed?), affect (eg, is the physician emotionally dysregulated?), and relationships (eg, is the physician increasingly isolated?).36 Reluctance to identify such signs can delay access to care.38

Table 2 provides an overview of burnout screening tools.

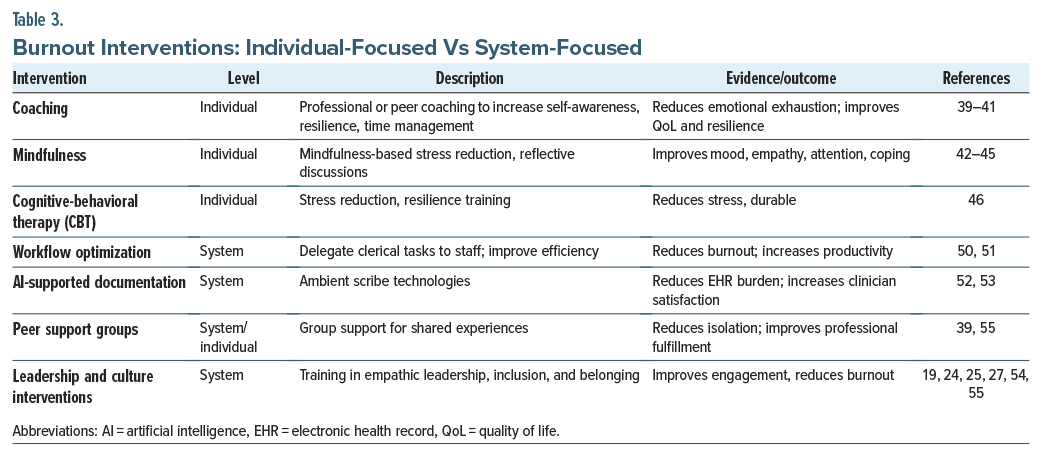

What Are Individual Approaches to Burnout and How Can They Promote Resilience?

Personalized coaching offers a proactive approach to burnout so that physicians can focus on self-developed, goal-oriented changes.39 Coaching, offered by trained peers or professional coaches, cultivates greater self-awareness and emotional intelligence and facilitates the development of strategies that foster resilience to stress. Through coaching, physicians receive support and validation of their achievements; identify, seek, and continue to engage in professional activities that bring joy (while anticipating and preventing problems); practice time management; and learn to set boundaries on work. Coaching may also incorporate motivational interviewing to sustain behavioral change. Through coaching, physicians can enhance their agency over the structural and cultural drivers of burnout.39–41

Data from randomized controlled trials and meta-analyses demonstrate that coaching improves emotional exhaustion and quality of life for physicians. Follow-up assessment on burnout and goal progress can help reinforce adaptive strategies.39–41

Another strategy, mindfulness, describes the practice of noticing one’s internal condition and surroundings with curiosity, openness, and acceptance42; its use supports psychological health and builds resilience. In the workplace, the incorporation of mindfulness improves attention, assists with complex decision-making, and helps employees enhance their coping skills43 to help offset elevated levels of burnout and job dissatisfaction among physicians. Fortunately, the affordability and adaptability of mindfulness-based interventions make them suitable for a diverse range of health care settings (including hospitals, rehabilitation centers, and outpatient clinics). Mindfulness in these settings can be introduced via longitudinal curricula and training sessions, reflective discussions that instill a culture of wellness, self-improvement, and open communication.42,43

Proponents of mindfulness have incorporated a variety of methods to address the growing problem of burnout in primary care. Upon completion of one program, primary care providers answered several questionnaires including the 2-Factor Mindfulness Scale, the MBI, and the Profile of Mood States; results showed measurable improvements in mood, empathy, and interpersonal relatedness.44

Other evidence-based interventions like the Mindfulness-Based Stress Reduction program have improved emotional awareness, mitigated stress, and fostered resilience.42 Some workplaces have incorporated “mindful moments” into the workday to provide integrated opportunities to improve employee mental health and well-being. Through regular use of mindfulness practices, physicians can become more comfortable with clinical uncertainty and enhance their collaborations with other physicians.45

In addition to mindfulness, meta-analyses demonstrate outcomes of reduced stress through at least 1 study on the use of eye-movement desensitization therapy. Additionally, cognitive-behavioral therapy approaches to reduce stress in physicians with burnout have demonstrated efficacy and durability. These strategies can be tailored to individual work-related stressors and personal preferences.46

What Can Health Care Systems Do to Reduce Burnout?

Rather than placing the burden of change on individual physicians, responsibility for mitigating burnout should be shifted to health care systems. With more than three-quarters of physicians now working in systems, health care organizations have a moral and financial imperative to address burnout. Physicians with burnout are apt to leave clinical practice (which leads to increased costs associated with turnover/replacement of staff who have left), generate less revenue (because of decreased productivity), and withdraw from organizational tasks and are prone to have worse patient outcomes and satisfaction.47,48

Health care systems are uniquely positioned to make impactful change on burnout by implementing policies that maximize workplace efficiency and promote a culture of well-being.49 Administrative tasks (eg, billing, documentation, and interfacing with health care insurance companies) consume nearly twice as much time as the time spent with patients.50 Therefore, health care systems should prioritize the redelegation of nonphysician tasks to support staff (eg, scribes, medical assistants, and administrative assistants).50,51 Implementation strategies to achieve this include workflow audits to identify tasks that can be redelegated, training for support staff on documentation or communications tasks, and design of clear protocols and responsibilities to ensure role clarity. However, barriers to implementation include the costs of hiring and training staff.50,51

Investing in artificial intelligence (AI)–supported ambient and automated documentation technologies also mitigates burnout because of reduced time spent in the EHR.52,53 Here, implementation strategies include the use of pilot programs in high-volume clinics with assessment of outcomes such as documentation time, clinician satisfaction, and error rates. Cost, workflow disruption, and compliance with privacy, security, and regulation can be critical barriers that systems must overcome to deploy AI effectively. 52,53

Since a culture of well-being mitigates burnout, health care leaders should be trained to advocate for physicians’ needs, to model respectful and empathic work relationships, and to foster an inclusive workplace culture.54 Making decisions transparent, distributing workloads fairly, providing timely responses to complaints of mistreatment and discrimination, and conveying appreciation for physicians’ contributions promote clinician engagement and professional fulfillment.55 Organizations must permeate the language, values, and behaviors that reinforce physicians’ sense of agency, humanism, community, inclusion, and belonging.22–25 Creating a vibrant community (replete with psychological safety so that physicians can offer feedback without fearing retribution) is also critical.26

Mitigating burnout also requires that health care systems support and promote physician work-life integration, while ensuring that organizational and individual values are aligned. This begins with destigmatizing burnout, including providing care for those who are burning out by instituting intentional screening, followed by opt-in identification.33–36 Early identification allows for timely interventions (including accessible mental health, coaching services, and participation in peer support groups) to enhance resilience.56 Improved work-life integration also requires that health care systems support physician responsibilities outside of the workplace. Concrete solutions include offering robust leave policies, subsidies for family planning, flexible scheduling, and emergency on-site care for their dependents. Transparent communication that values physicians’ perspectives in decision-making and aligns organizational and individual values is critical to create meaning and agency for providers and mitigate burnout.23,24 Academic institutions must also recognize that clinical teaching is as valuable as research productivity, particularly regarding promotions.57

Table 3 provides an overview of burnout interventions.

What Happened to Dr A?

After a particularly difficult week, Dr A had a lengthy conversation with her husband. She discussed how upset she was about herself and her work. Given that Dr A’s husband had noticed Dr A’s recent lack of enjoyment at work, he shared his own concerns. Their conversation helped Dr A to identify her burnout. She now understood that burnout was not just affecting her clinical practice but also affecting her life outside of work.

Dr A decided her next step should be to schedule a meeting with her clinic’s leadership team. Dr A found that her team was supportive; they identified ways to address her burnout and made an investment in ambient documentation to lessen everyone’s documentation burden. In addition, the leadership team agreed that the nurse working with Dr A should take on additional tasks (including triaging all patient messages and calls, assisting with preparation of prior authorization requests, and making sure that all clinical documents, including discharge summaries and consultation notes, were available in the medical record the day before appointments). In addition, Dr A decided to reduce her workload by decreasing her clinical schedule from 5 days a week to 4 days a week. This gave her more time to focus on her well-being. Dr A also decided to prioritize her physical health; she joined a gym and began to exercise 3 days a week. She joined a peer support group with other physicians who were experiencing burnout. Understanding that she was not alone and problem-solving with people who shared her experiences was extremely helpful.

Over the next few months, Dr A’s stress level decreased. She began sleeping better at night and felt less exhausted during the day. Her headaches became less frequent and intense and then disappeared. She found herself enjoying interactions with her patients, and these encounters became more fulfilling once again. Dr A’s irritability outside of work resolved, and her family and friends remarked that she seemed like “her old self” again. Dr A agreed.

CONCLUSION

Although some of the symptoms of burnout and depression can overlap, burnout has specific causes, features, and treatment approaches. The etiologies for physician burnout are multifactorial and specifically related to work (eg, excessive workload and time pressure, lack of control and autonomy, administrative and clerical burden, work-home conflict and poor work-life integration, and negative organizational culture and leadership). Additionally, structural (workplace policies and norms, acess to support, resources or flexibility, pay structure, job security, and secheduling practices) and demographic factors (identifying as a woman, younger age, midcareer stage, caregiving responsibilities, and membership in historically marginalized racial or ethnic groups) further influence vulnerability to burnout.

Health care systems can improve burnout by implementing structures (policies, programs, processes) to delegate clerical tasks, optimize workflows, provide coaching or peer support, and support flexible scheduling that aligns organizational and individual values. For clinicians like Dr A, these measures can enhance professional fulfillment. Addressing burnout at the institutional level not only supports clinician well-being but also enhances workforce retention, reduces health care costs, and improves patient outcomes, quality, and access to care.

Article Information

Published Online: February 10, 2026. https://doi.org/10.4088/PCC.25f04061

© 2026 Physicians Postgraduate Press, Inc.

Submitted: August 17, 2025; accepted October 30, 2025.

To Cite: Nadkarni A, Donovan AL, Gonzalez C, et al. Facilitating physician well-being: assessment and interventions for burnout. Prim Care Companion CNS Disord 2026;28(1):25f04061.

Author Affiliations: Harvard Medical School, Boston, Massachusetts (Nadkarni, Donovan, Gonzalez, Mehta, Stern); Department of Psychiatry, Mass General Brigham, Boston, Massachusetts (Nadkarni, Donovan, Gonzalez, Mehta, Stern); Department of Medicine, Mass General Brigham, Boston, Massachusetts (Mehta); Brigham and Women’s Hospital/Harvard Medical School Psychiatry Residency, Boston, Massachusetts (Mastrangelo, Shen).

Nadkarni, Donovan, Gonzalez, Mehta, Mastrangelo, and Shen are co-first authors; Stern is senior author.

Corresponding Author: Ashwini Nadkarni, MD, Mass General Brigham/Harvard Medical School, Boston, Massachusetts ([email protected]).

Financial Disclosure: Dr Stern has received royalties from Elsevier for editing textbooks on psychiatry. Drs Nadkarni, Donovan, Gonzalez, Mehta, Mastrangelo, and Shen report no financial relationships.

Funding/Support: None.

Clinical Points

- When the stress of practicing medicine exceeds a clinician’s capacity for resilience (ie, the adaptive capacity to respond to stress and withstand adversity), burnout can arise.

- Physicians (even after the COVID-19 pandemic) continue to have a higher risk of burnout than other US workers.

- Health care organizations can help their at-risk staff by using empirically supported screening tools (eg, the Maslach Burnout Inventory, the Oldenburg Burnout Inventory, and the Stanford Professional Fulfillment Index) to help diagnose burnout and distinguish burnout from depression. Empirically supported approaches should be implemented at the individual and system levels.

References (57)

- Shanafelt TD, Boone S, Tan L, et al. Burnout and satisfaction with work-life balance among US physicians relative to the general US population. Arch Intern Med. 2012;172(18):1377–1385. PubMed CrossRef

- Jain FA, Madarasmi S. Mindfulness and Resilience. In: Stern TA, Wilens TE, Fava M, eds. Massachusetts General Hospital Comprehensive Clinical Psychiatry. 3rd ed. Elsevier; 2025:1005–1013.

- Donovan AI, Sheets J, Stern TA. Coping with the Rigors of Psychiatric Practice. In: Stern TA, Wilens TE, Fava M, eds. Massachusetts General Hospital Comprehensive Clinical Psychiatry. 3rd ed. Elsevier; 2025:997–1004. CrossRef

- Rotenstein LS, Torre M, Ramos MA, et al. Prevalence of burnout among physicians: a systematic review. JAMA. 2018;320(11):1131–1150. PubMed CrossRef

- American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders. 5th ed, Text Rev. APA; 2022.

- Koutsimani P, Montgomery A, Georganta K. The relationship between burnout, depression, and anxiety: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Front Psychol. 2019;10:284. PubMed CrossRef

- Parker G, Tavella G. Distinguishing burnout from clinical depression: a theoretical differentiation template. J Affect Disord. 2021;281:168–173. PubMed CrossRef

- Tavella G, Hadzi-Pavlovic D, Bayes A, et al. Burnout and depression: points of convergence and divergence. J Affect Disord. 2023;339:561–570. PubMed CrossRef

- Shanafelt TD, West CP, Sinsky C, et al. Changes in burnout and satisfaction with work-life integration in physicians and the general US working population between 2011 and 2017. Mayo Clin Proc. 2019;94(9):1681–1694. PubMed CrossRef

- Shanafelt TD, West CP, Sinsky C, et al. Changes in burnout and satisfaction with work-life integration in physicians and the general US working population between 2011 and 2020. Mayo Clin Proc. 2022;97(3):491–506. PubMed CrossRef

- Shanafelt TD, West CP, Sinsky C, et al. Changes in burnout and satisfaction with work-life integration in physicians and the general US working population between 2011 and 2023. Mayo Clin Proc. 2025;100(7):1142–1158. PubMed CrossRef

- Linzer M, Jin JO, Shah P, et al. Trends in clinician burnout with associated mitigating and aggravating factors during the COVID-19 pandemic. JAMA Health Forum. 2022;3(11):e224163. PubMed CrossRef

- Macaron MM, Segun-Omosehin OA, Matar RH, et al. A systematic review and meta-analysis on burnout in physicians during the COVID-19 pandemic: a hidden healthcare crisis. Front Psychiatry. 2023;13:1071397. PubMed CrossRef

- Belkić K. Toward better prevention of physician burnout: insights from individual participant data using the MD-specific Occupational Stressor Index and organizational interventions. Front Public Health. 2025;13:1514706. PubMed CrossRef

- West CP, Dyrbye LN, Shanafelt TD. Physician burnout: contributors, consequences, and solutions. J Intern Med. 2018;283(6):516–529. PubMed CrossRef

- Dillon EC, Stults CD, Deng S, et al. Women, younger clinicians, and caregivers’ experiences of burnout and well-being during COVID-19 in a US healthcare system. J Gen Intern Med. 2022;37(1):145–153. PubMed CrossRef

- Martinez KA, Sullivan AB, Linfield DT, et al. Change in physician burnout between 2013 and 2020 in a major health system. South Med J. 2022;115(8):645–650. PubMed CrossRef

- Paradis KC, Kerr EA, Griffith KA, et al. Burnout among mid-career academic medical faculty. JAMA Netw Open. 2024;7(6):e2415593. PubMed CrossRef

- Nadkarni A, Shen M, Temkin S, et al. Reducing burnout in women physicians: an organizational roadmap from the Harvard Radcliffe Institute exploratory seminar. J Womens Health (Larchmt). 2025;34(10):1183–1191. doi:10.1089/jwh.2025.0001. PubMed CrossRef

- 2023 Women Physicians of Color Study. A Prescription for Change: Addressing Retention Among Women Physicians of Color in California. Physicians for a Healthy California. https://www.phcdocs.org/Portals/0/assets/docs/wpoc/WPOC%20Final%20Report%202024%20-%20final.pdf. Accessed October 13, 2025.

- Samuels EA, Boatright DH, Wong AH, et al. Association between sexual orientation, mistreatment, and burnout among US medical students. JAMA Netw Open. 2021;4(2):e210214.

- The Stanford Model of Occupational Wellbeing. https://wellmd.stanford.edu/about/model-external.html. Accessed June 17, 2025.

- National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine, Committee on Systems Approaches to Improve Patient Care by Supporting Clinician Well-Being. Taking Action Against Clinician Burnout: A Systems Approach to Professional Well-Being. National Academies Press; 2019. CrossRef

- Shanafelt T, Trockel M, Rodriguez A, et al. Wellness-centered leadership: equipping health care leaders to cultivate physician well-being and professional fulfillment. Acad Med. 2021;96(5):641–651. PubMed CrossRef

- Nadkarni A, Kroll DS, Silbersweig DA. After patient suicide: fostering a culture of patient safety and clinician well-being to improve quality of care. Harv Rev Psychiatry. 2025;33(4):239–241. PubMed CrossRef

- Shanafelt TD, West CP, Dyrbye LN, et al. Changes in burnout and satisfaction with work-life integration in physicians during the first 2 years of the COVID-19 pandemic. Mayo Clin Proc. 2022;97(12):2248–2258. PubMed CrossRef

- Nadkarni A, Harry E, Rozenblum R, et al. Understanding perceived appreciation to create a culture of wellness. Acad Psychiatry. 2022;46(2):228–232. PubMed CrossRef

- Dyrbye LN, West CP, Sinsky CA, et al. Physicians’ experiences with mistreatment and discrimination by patients, families, and visitors and association with burnout. JAMA Netw Open. 2022;5(5):e2213080. PubMed CrossRef

- Nadkarni A, Behbahani K, Fromson J. When compromised professional fulfillment compromises professionalism. JAMA. 2023;329(14):1147–1148. PubMed CrossRef

- Shanafelt TD, Wang H, Leonard M, et al. Assessment of the association of leadership behaviors of supervising physicians with personal-organizational values alignment among staff physicians. JAMA Netw Open. 2021;4(2):e2035622. PubMed CrossRef

- Nadkarni A, Bhattacharyya S, Becker M, et al. A pilot of academic coordination improves faculty burnout and enhances support for the academic mission. Acad Psychiatry. 2024;48:1–2. PubMed

- Sinsky CA, Brown RL, Stillman MJ, et al. Politicization of medical care, burnout, and professionally conflicting emotions among physicians in the United States. Mayo Clin Proc. 2023;98(11):1752–1764.

- National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine. Valid and reliable survey instruments to measure burnout, well-being, and other work-related dimensions. https://nam.edu/product/valid-and-reliable-survey-instruments-to-measure-burnout-well-being-and-other-work-related-dimensions/. Accessed August 13, 2025.

- Ong J, Lim WY, Doshi K, et al. An evaluation of the performance of five burnout screening tools: a multicentre study in anaesthesiology, intensive care, and ancillary staff. J Clin Med. 2021;10(21):4836. PubMed CrossRef

- Trockel M, Bohman B, Lesure E, et al. A brief instrument to assess both burnout and professional fulfillment in physicians: reliability and validity, including correlation with self-reported medical errors, in a sample of resident and practicing physicians. Acad Psychiatry. 2018;42(1):11–24. PubMed CrossRef

- Brady KJ, Sheldrick RC, Ni P, et al. Examining the measurement equivalence of the Maslach Burnout Inventory across age, gender, and specialty groups in US physicians. J Patient Rep Outcomes. 2021;5(1):43. PubMed CrossRef

- Kroenke K, Spitzer RL, Williams JB. The PHQ-9: validity of a brief depression severity measure. J Gen Intern Med. 2001;16(9):606–613. PubMed CrossRef

- Hellwig T, Rook C, Floren-Treacy E, et al. An early warning system for your team’s stress level. Harv Bus Rev. https://hbr.org/2017/04/an-early-warning-system-for-your-teams-stress-level. Accessed August 13, 2025.

- Kiser SB, Sterns JD, Lai PY, et al. Physician coaching by professionally trained peers for burnout and well-being: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA Netw Open. 2024;7(4):e245645. PubMed CrossRef

- Boet S, Etherington C, Dion PM, et al. Impact of coaching on physician wellness: a systematic review. PLoS One. 2023;18(2):e0281406. PubMed CrossRef

- Kiser SB, Sterns JD, Lai PY, et al. Physician coaching by professionally trained peers for burnout and well-being: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA Netw Open. 2024;7(4):e245645. PubMed CrossRef

- Kabat-Zinn J. Mindfulness-based interventions in context: past, present, and future. Clin Psychol Sci Pract. 2003;10:144–156. CrossRef

- Fazia T, Bubbico F, Berzuini G, et al. Mindfulness meditation training in an occupational setting: effects of a 12-week mindfulness-based intervention on wellbeing. Work. 2021;70(4):1089–1099. PubMed CrossRef

- Krasner MS, Epstein RM, Beckman H, et al. Association of an educational program in mindful communication with burnout, empathy, and attitudes among primary care physicians. JAMA. 2009;302(12):1284–1293. PubMed CrossRef

- Lamothe M, Rondeau É, Malboeuf-Hurtubise C, et al. Outcomes of MBSR or MBSR-based interventions in health care providers: a systematic review with a focus on empathy and emotional competencies. Complement Ther Med. 2016;24:19–28. PubMed CrossRef

- Catapano P, Cipolla S, Sampogna G, et al. Organizational and individual interventions for managing work-related stress in healthcare professionals: a systematic review. Med Kaunas. 2023;59(10):1866. PubMed CrossRef

- Salvado M, Marques DL, Pires IM, et al. Mindfulness-based interventions to reduce burnout in primary healthcare professionals: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Healthc (Basel). 2021;9(10):1342. PubMed CrossRef

- Shanafelt TD, Hasan O, Dyrbye LN, et al. Changes in burnout and satisfaction with work-life integration in US physicians between 2011 and 2014. Mayo Clin Proc. 2015;90(12):1600–1613. PubMed CrossRef

- Panagioti M, Geraghty K, Johnson J, et al. Association between physician burnout and patient safety, professionalism, and patient satisfaction: a systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA Intern Med. 2018;178(11):1317–1330. PubMed CrossRef

- Rao SK, Kimball AB, Lehrhoff SR, et al. The impact of administrative burden on academic physicians: results of a hospital-wide physician survey. Acad Med. 2017;92(2):237–243. PubMed CrossRef

- Sinsky C, Colligan L, Li L, et al. Allocation of physician time in ambulatory practice: a time and motion study in 4 specialties. Ann Intern Med. 2016;165(11):753–760. PubMed CrossRef

- Cheng T, Shanafelt TD, Nasca TJ. Ambient artificial intelligence scribes to alleviate the burden of documentation. N Engl J Med Catalyst. 2024;5(3). doi:10.1056/CAT.23.0404. CrossRef

- O’Donnell HC, Fung C, Vargas H, et al. Clinician experiences with ambient scribe technology to assist patient care. JAMA Netw Open. 2025;8(2):e2830383.

- Burns KE, Pattani R, Lorens E, et al. The impact of organizational culture on professional fulfillment and burnout in an academic department of medicine. PLoS One. 2021;16(6):e0252778. PubMed CrossRef

- Tawfik DS, Profit J, Webber S, et al. Organizational factors affecting physician well-being. Curr Treat Options Pediatr. 2019;5(1):11–25. PubMed CrossRef

- Petrie K, Stanton K, Gill A, et al. Effectiveness of a multi-modal hospital-wide doctor mental health and wellness intervention. BMC Psychiatry. 2022;22(1):244. PubMed CrossRef

- Boamah SL, Laschinger HK. The influence of values congruence on burnout and job satisfaction in nurses. J Nurs Manag. 2016;24(4):514–525.

Enjoy this premium PDF as part of your membership benefits!