Abstract

This article describes a preclinical training program for medical students conducted in a state psychiatric hospital for more than 3 decades. Small groups of students and instructors interviewed patients about their experience with mental illness and participated in follow-up discussions. The students’ post-training feedback demonstrates how empathy can evolve within the context of an emotionally powerful firsthand experience. This raises the question of whether direct contact with psychiatric inpatients with serious mental illness in the early years of medical school can reduce stigmatization and improve empathy. More research in this area is needed.

Prim Care Companion CNS Disord 2025;27(4):25m03923

Author affiliations are listed at the end of this article.

In clinical medicine, empathy is the ability of a physician to recognize and understand a patient’s perspective and feelings, as if the physician was experiencing those feelings.1 The physician conveys this understanding back to the patient. Empathy has affective and cognitive components. Affective empathy is the capacity to experience the feelings of another person. Cognitive empathy is the capacity to see things from the perspective of another person.2

Recent empathy literature has raised questions about the development of empathy in medical school and demonstrates conflicting trends.3 Does training decrease empathy4 or can empathy be maintained during medical education?5 As medical school progresses, does the hidden curriculum (influences such as poor role models and time pressure) produce a barrier to empathy?6 Do students distance themselves from empathic approaches to protect themselves emotionally?7

Certain educational interventions8 have been shown to improve empathy. These interventions include videos of patient encounters9 and interviews with simulated patients.10 However, these approaches do not involve direct patient contact. Howick et al6 caution about formulaic, “tick-box” approaches to fostering empathy. According to some studies,7 students express frustration with lack of hands-on contact, especially in the early years, and prefer direct patient contact. Seeing a multiplicity of patients is deemed by Seeberger et al5 to be a promoter of empathy.

We describe a preclinical training program that emphasizes direct patient contact. It is a long-running course that introduces preclinical medical students to hospitalized individuals with serious mental illness (SMI). We give examples of anonymous student feedback that elucidate this early experience of direct patient contact.

DESCRIPTION OF THE PROGRAM

For over 3 decades, Albert Einstein College of Medicine has run a preclinical course for medical students entitled, Introduction to Clinical Medicine (ICM). The course teaches clinical skills for patient encounters and is graded on a pass/fail basis. It is a first-year course that includes a visit to a psychiatric hospital near the end of the first year.

Numerous hospitals have hosted the ICM groups, with ∼12 students and 2 faculty per group. The ICM group leaders are attending physicians (across various specialties, including psychiatry) and other medical school faculty. Prior to their visit, students attend a preparatory ICM session. This session includes a 1-hour lecture on the mental status examination, followed by a 2½-hour small group session for skills practice. The students interview 2 simulated patients, with actors portraying the psychiatric patients. One patient has psychotic symptoms and the other severe depressive symptoms. The group discusses the nature of the inpatient milieu, the professional protocol on the units, locked units and their restrictions, and expected patient behaviors.

The objectives of the psychiatric ward visit are to demonstrate a structured interview of a patient with a psychiatric history, mental status examination, and exploration of social determinants of health; to identify the signs and symptoms of psychiatric illness; to address students’ fears and anxieties; and to write both a narrative reflection essay and a standard case write-up. These objectives are shared with and discussed among the students and ICM group leaders.

At our hospital, the training director chooses the participating wards and attending psychiatrists, who are faculty members with teaching expertise. Psychiatry residents participate with their attending. The attending psychiatrists choose patients who can participate in a 30-minute interview. Patients give their permission prior to the interview.

The ward visit typically runs for 2½ hours. There is a 15-minute tour, during which students are given an overview of the hospital and patient population. The ICM leaders prepare the group by describing the interview structure, and they answer questions and concerns. Two students volunteer to interview. The attending psychiatrist introduces the first patient to the group. The ICM group leaders supervise the student’s interview while the attending psychiatrist monitors the patient. The interview proceeds for a half hour, followed by a half-hour discussion. This same procedure is repeated with a second patient interview and discussion over the next hour. The psychiatric patients typically have schizophrenia or schizoaffective disorder, along with complex psychosocial histories. In the interviews, patients describe their break with reality, paranoia, fear, worsening estrangement, and/or social isolation.

Following the interview, the group and the attending psychiatrist discuss the experience of psychosis and long-term hospitalization. During these postinterview discussions, students are encouraged to share their personal reactions to the interview. The attending psychiatrists answer students’ questions about the patient. The ICM group leaders give feedback on the interview.

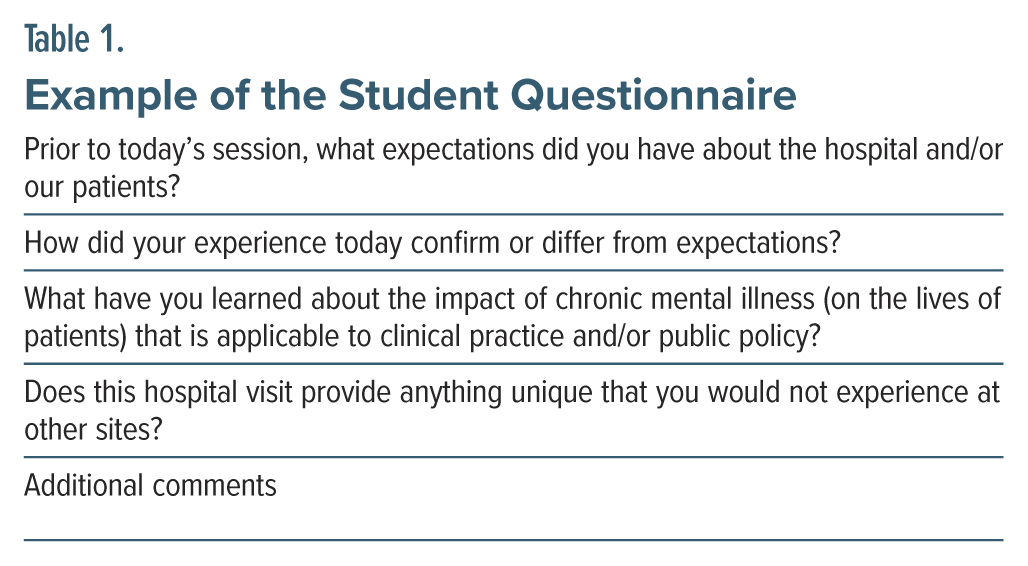

Before departure from our hospital, the students are given a questionnaire (Table 1) for anonymous written feedback regarding expectations and impressions of the visit. The responses discussed in this article are from 2009 to 2022. The feedback was used to improve the program. One of the students’ concerns was their inexperience interviewing people with psychotic illness. This was addressed by introducing simulated patient interviews prior to the visit.

After the visit, students are required to submit a patient write-up based on 1 patient interview and a reflective essay about their experience. The write-ups and essays are reviewed by their ICM group leaders, who provide written feedback. The experiences are not graded.

EXAMPLES OF STUDENT FEEDBACK

Previsit Expectations of the Patients and Wards

Students had expectations that the patients would be violent, aggressive, or dangerous.

“Expected unpredictable, possibly violent patients.”

“I expected very ill patients, with some violent and criminal pasts.”

Students expressed their personal concerns. Some felt frightened.

“I was scared. I was expecting violence, verbal threats.”

“I was nervous about interviewing patients, thinking we could trigger a mental event.”

Because students—and not their instructors—would be interviewing the patients, they expressed concern that the patients would be difficult to understand and hard to interview.

“I thought that patients with chronic mental illness would demonstrate a lack of awareness and an inability to effectively communicate ideas.”

“I was concerned that it would not be something I could handle.”

“Stereotypes of dangers, criminals, also incoherent conversations that impair interview.”

Regarding the hospital wards, the students expected the wards would be grim as well as rowdy, chaotic, and difficult to control.

“I expected a grim, frightening setting.”

“I thought they would be very disturbed and that the ward would be rowdy.”

“Expected the center to be more chaotic and the patients more aggressive.”

Possibly influenced by the media, which portrays older, more asylum-like institutions, students described expectations of a prison with high security.

“I just thought it would be a crazy house with high security and locked doors everywhere.”

“I thought the patients were going to be in straitjackets and locked in their rooms.”

Students directly referenced movies and television shows that molded their preconceptions.

“Something along the lines of One Flew Over the Cuckoo’s Nest.”

“I expected to walk into Arkham Asylum.”

“Shutter Island.”

Were Negative Expectations Confirmed?

It was not possible to determine what percentage of students had negative expectations confirmed by the visit. Some expressed dismay at the severity of illness and the extent of the delusions. For others, the stigma persisted: “Crazies need to be locked up.” Although it was early in training, they did not see psychiatry as a career choice: “Not for me, for sure.”

“I expected very sick, violent, delusional patients and the experience met all of my expectations.”

“I was startled at the level of mental illness of the patients.”

“The delusions that people have run very deeply, even when being treated.”

For some, their expectations were confirmed, but it was a learning experience.

“This was a valuable experience even if somewhat unnerving.”

“BPC is scary, sad, disturbing. It’s a hard experience but needed.”

For others, it was less extreme than expected.

“Patients were very well-behaved and mostly in control of themselves which I didn’t expect.”

“The atmosphere was more like a nursing home.”

“The patients were friendlier/more outgoing/more willing to talk than what I expected.”

Students Had Emotional Responses

After the visit, students expressed sadness for the patients they encountered, describing mental illness as “heartbreaking,” “devastating,” and “a tragedy.” Students empathized with how “depressing” and “painful” mental illness must be.

“Seeing how troubled and how entrapped they were in their delusions. I felt bad for our 2 patients.”

“It made me very sad to talk to such unfortunate people.”

“Chronic mental illness seems to be incredibly difficult and a constant worry. I can’t imagine the pain these people must be experiencing.”

“Chronic mental illness must feel frustrating, depressing, desperate to get better.”

Students expressed that mental illness must be frustrating due to a lack of freedom or control over one’s life, feeling “trapped,” “highly controlled,” “helpless,” and a “sense of powerlessness.”

“Must be frustrating, alienating. May be hard to do simple tasks that we take for granted.”

“Frustrating because there is feeling of lack of control.”

Amid the Emotional Responses, There was Learning (Cognitive Empathy)

From the visit, students learned about the “debilitating” nature of mental illness.

“Chronic mental illness derails a person’s entire life.”

“Chronic mental illness can really change a person completely and leave them very vulnerable to society.”

They learned about the ongoing isolation that patients face.

“Mental illness can be scary and can alienate you from the people you love.”

“Living with a mental illness seems like an incredibly lonely experience.”

Students learned that mental illness is not always apparent.

“Mental illness isn’t always glaringly obvious.”

“I learned that normal-appearing patients can still have severe mental disorders.”

Students learned that mental illness is difficult to treat and expressed discouragement that some will not recover.

“Many of the patients are stuck in a cycle of leaving and coming back in.”

“It is saddening and a little discouraging to see that for some people, nothing could be done.”

“Mental illness seems to be a huge burden, and in many cases can’t be cured. It’s fairly depressing.”

Was It Possible to Empathize?

Students were concerned about their ability to empathize because their backgrounds were so different.

“It was very interesting and hard because it was difficult to empathize. There are vast differences in life experience.”

“I have to be aware that personal issues and history can be different from mine, relating to issues I may not fully understand.”

“It is difficult for me to put myself in their shoes.”

Despite their differences, students came to realize the patients were not “bad people.” Patients were people like themselves.

“My experience made me realize that these individuals have some cognitive deficits, and they were not “bad” or crazy people like I thought.”

“It’s a very serious disease out of their control, and they need all of our support because it doesn’t have anything to do with them.”

Students were open to learning empathy from the patients themselves. The patients told them they wanted to be treated “as humans” and that “everyone is a person.” “You need to have love in your heart and be understanding.” Even the sickest patients need to be cared for with compassion.

One student wrote that it was important to “be open-minded and listen to mentally ill patients.” Others spoke of the training exercise as follows:

It “provides an opportunity to get into the minds of some patients and maybe understand why they’re here and empathize with them.”

It “allows us to get a better understanding of mental illness that I wouldn’t get elsewhere. Walking through the hallways, I felt like I had stepped in the shoes of a patient.”

“A single experience is not enough to get a feel for a chronic disease, but I certainly developed empathy.”

Empathy is negatively correlated with stigma or prejudice.11 Students identified stigma as “so powerful and strong” and “created largely by those who don’t deal closely with the mentally ill.” For some, stigmatizing attitudes decreased after the visit.

“Any preconceived notions or ideas you develop prior to visiting a patient should be discarded.”

“I learned to not stigmatize.”

“Every patient is very different, and you should never enter the room with any expectations.”

The Problem of Differentiating Fact From Delusion and the Development of Empathy

For the students, delusions made it difficult to take a history and to empathize in the process. They could not discern what was true and not true, what was real and not real. If a statement was false (not real), did the patient know it was false (“putting them on”) or not know (delusional)?

“Very difficult to take a thorough patient history and to figure out the credibility of the stories.”

“Chronic mental illness . . . provides obstacles for taking a history. What’s real?”

“I was very surprised to learn what parts of the interview were false/fabricated.”

Despite the difficulties, students empathized with the experience of an altered reality.

“It seems scary and very debilitating. There are worlds created in the patients’ heads that do not fit in our reality.”

“It must be very difficult to see the world one way when everyone else sees it another way.”

“It sounds absolutely frightening to have no control over your own mind and sense of reality.”

DISCUSSION

For over 3 decades, the Albert Einstein College of Medicine has introduced students to hospitalized psychiatric patients in their first preclinical year. Students meet individuals with severe and chronic mental illness, often for the first time. For many students, their only prior exposure to SMI was through the media, where damaging stereotypes are perpetuated12 and people with SMI are portrayed as dangerous and incompetent.13 Students described their influences: One Flew Over the Cuckoo’s Nest, a movie in which abusive staff give lobotomies as punishment; Batman: Arkham Asylum, a video game filled with criminally insane supervillains; and Shutter Island, a movie where psychiatrists experiment on criminally insane patients. These portrayals can evoke prejudices leading to stigmatization and make it difficult to empathize.

Other factors that lead to stigmatization include lack of understanding of mental illness,14 discomfort and fear during patient contact, and lack of knowledge as to how to behave with patients.15 The ICM program addresses each of these factors by providing information on psychosis prior to and during the small group discussions and instructing students on how to interact with patients.

In contrast to factors that lead to early prejudice, there are factors that decrease stigmatization in students entering medical school. For example, stigmatizing attitudes are reduced in students with family members or friends with mental illness.16,17 Having a personal experience humanizes mental illness. According to the contact theory, direct contact with people with mental illness can improve attitudes and increase acceptance.18 Early patient contact, such as occurs in the ICM program, can counteract prejudice engendered by the media and the culture at large.19

In the study by Seeberger et al,5 medical students identified education-associated promoters of empathy: seeing a variety of patients and encountering positive role models and educational activities that increased self-awareness. The preclinical ICM course introduces the students to a multiplicity of patients at different psychiatric hospitals. Our hospital enables them to meet patients with chronic psychotic disorders like schizophrenia and schizoaffective disorder. This is a powerful aspect of the program: the ability to speak with the individuals whom they expected to be “violent,” “disturbed,” or unable to “effectively communicate ideas.” Although some students felt their expectations were confirmed, others did not and found the patients “more willing to talk than what I expected.”

Patients shared insights about living in a hospital with a mental illness and instructed students on how to be more understanding: “Treat us as humans.” “Everyone is a person.” “You need to have love in your heart and be understanding.” ICM students used their interactions with the patients as “an opportunity to get into the minds of some patients . . . and empathize with them” and to “step in the shoes of a patient.” Students learned that patients were not “bad people” and that their mental illness was not their fault.

Students benefitted from positive role models, a promoter of empathy.5 The ICM group leaders are humanists with years of clinical and teaching experience. Many of the ward psychiatrists have dedicated their careers to treating people with chronic psychosis.

The program addresses inhibitors of empathy such as the complexity of patients’ socioeconomic situation and diseases and the over-emphasis on biomedical knowledge.6 The initial psychiatry visit emphasizes psychosocial knowledge, and despite the psychosocial complexity of the histories, the students learned. They learned how symptoms vary in different individuals and how the severity of mental illness may be difficult to discern by its presentation. They learned how mental illness can consume a person and derail the trajectory of their life. It is isolating and lonely to live in a hospital and be separated from family and friends.

The small groups provided a safe place where students could reflect upon and share their reactions and feelings: “I felt bad for our 2 patients.” “It made me very sad.” “It is saddening and a little discouraging.” “It’s fairly depressing.” The question remains as to whether students could modulate their emotions and settle into a form of cognitive empathy. For example, some students were frustrated by the patients’ delusions and lack of a truthful history. “What is real, what is not real? How can I even talk to this person?” Some used the small group discussions to move from this place of frustration and anxiety to an empathic conceptualization, such as “It must be very difficult (debilitating/frightening) to see the world one way when everyone else sees it another way.”

CONCLUSION

We describe a medical school program that provides direct contact with psychiatric inpatients in the first year of training. Reactions to the program are described in the students’ own words. Student responses indicate that early exposure to patients with SMI can reduce anxiety and stigmatizing attitudes, as well as increase empathy. However, it is not clear how pervasive this change was and whether it would continue into the clinical years.

The postinterview discussion groups are a necessary component of the program. They provide a supportive environment in which to share emotions elicited by a powerful firsthand experience. The groups can channel emotions into a cognitive awareness of the experience of severe mental illness.

In future programs, empathy can be better assessed using an empathy scale before and after each visit, such as the Jefferson Scale of Empathy (JSE).20 The JSE is a 20-item instrument that measures empathy in health care providers in patient care situations. It has been employed in multiple studies of medical student empathy.4,9

The ICM course will continue to address bias and stereotyping of people with mental illness, and there are plans to put an increased emphasis on empathy in the context of the simulated practice interviews and psychiatric ward visits. Recognizing, understanding, and utilizing empathy as a key component of clinical practice is a central theme of the ICM program.

Our culture stigmatizes people with SMI. New medical students bring these stereotypes and misconceptions into medical school. Early patient contact enables students to question these preconceptions and facilitates empathetic interactions. We encourage other medical schools to include such a preclinical program in their curricula if they have not already done so.

Article Information

Published Online: July 29, 2025. https://doi.org/10.4088/PCC.25m03923

© 2025 Physicians Postgraduate Press, Inc.

Submitted: January 7, 2025; accepted May 12, 2025.

To Cite: Woesner ME, Cheung AM. A preclinical medical student program: student reactions to interviewing psychiatric inpatients. Prim Care Companion CNS Disord 2025;27(4):25m03923.

Author Affiliations: Department of Psychiatry, Bronx Psychiatric Center, Bronx, New York (Woesner); Department of Psychiatry and Behavioral Sciences, Albert Einstein College of Medicine, Bronx, New York (Woesner); Albert Einstein College of Medicine, Bronx, New York (Cheung).

Corresponding Author: Mary E. Woesner, MD, Department of Psychiatry, 1st Floor Clinicians Ste, Adult Building, Bronx Psychiatric Center, 1500 Waters Place, Bronx, NY 10461 ([email protected]).

Relevant Financial Relationships: None.

Funding/Support: None.

Acknowledgment: The authors thank Daniel C. Myers, LCSW (Albert Einstein College of Medicine, Bronx, NY) for insights on the pre-clinical training program. Mr Myers has no relevant financial relationships to declare.

Clinical Points

- Preclinical medical students may have stigmatizing attitudes toward mental illness.

- Supervised group interviews with psychiatric inpatients can help decrease stigmatization and increase empathy.

- A similar preclinical experience can be integrated into medical school curricula.

References (20)

- Hersen M, Hasselt VB. Basic Interviewing: A Practical Guide for Counselors and Clinicians. Erlbaum; 1998.

- Mercer SW, Reynolds WJ. Empathy and quality of care. Br J Gen Pract. 2002;52(suppl):S9–S12. PubMed

- Ferreira-Valente A, Monteiro JS, Barbosa RM, et al. Clarifying changes in student empathy throughout medical school: a scoping review. Adv Health Sci Educ Theor Pract. 2017;22(5):1293–1313. PubMed CrossRef

- Hojat M, Mangione S, Nasca TJ, et al. An empirical study of decline in empathy in medical school. Med Educ. 2004;38(9):934–941. PubMed CrossRef

- Seeberger A, Lönn A, Hult H, et al. Can empathy be preserved in medical education?. Int J Med Educ. 2020;11:83–89. PubMed CrossRef

- Howick J, Dudko M, Feng SN, et al. Why might medical student empathy change throughout medical school? a systematic review and thematic synthesis of qualitative studies. BMC Med Educ. 2023;23(1):270. PubMed CrossRef

- Jeffrey D. A meta-ethnography of interview-based qualitative research studies on medical students’ views and experiences of empathy. Med Teach. 2016;38(12):1214–1220. PubMed CrossRef

- Batt-Rawden SA, Chisolm MS, Anton B, et al. Teaching empathy to medical students: an updated, systematic review. Acad Med. 2013;88(8):1171–1177. PubMed CrossRef

- Hojat M, Axelrod D, Spandorfer J, et al. Enhancing and sustaining empathy in medical students. Med Teach. 2013;35(12):996–1001. PubMed CrossRef

- Wündrich M, Schwartz C, Feige B, et al. Empathy training in medical students -a randomized controlled trial. Med Teach. 2017;39(10):1096–1098. PubMed

- McFarland S. Authoritarianism, social dominance, and other roots of generalized prejudice. Pol Psychol. 2010;31:453–477. CrossRef

- Wahl OF. Media madness: Public images of mental illness. Rutgers University Press; 1995.

- Stier A, Hinshaw SP. Explicit and implicit stigma against individuals with mental illness. Aust Psychol. 2007;42(2):106–117. CrossRef

- Thornicroft G, Rose D, Kassam A, et al. Stigma: ignorance, prejudice or discrimination?. Br J Psychiatry. 2007;190:192–193. PubMed CrossRef

- Phelan JC, Link BG. Fear of people with mental illnesses: the role of personal and impersonal contact and exposure to threat or harm. J Health Soc Behav. 2004;45(1):68–80. PubMed CrossRef

- Korszun A, Dinos S, Ahmed K, et al. Medical student attitudes about mental illness: does medical-school education reduce stigma? Acad Psychiatry. 2012;36(3):197–204. PubMed CrossRef

- Babicki M, Małecka M, Kowalski K, et al. Stigma levels toward psychiatric patients among medical students-A worldwide online survey across 65 countries. Front Psychiatry. 2021;12:798909. PubMed CrossRef

- Corrigan PW, Penn DL. Lessons from social psychology on discrediting psychiatric stigma. Am Psychol. 1999;54(9):765–776. PubMed CrossRef

- Corrigan PW, Morris SB, Michaels PJ, et al. Challenging the public stigma of mental illness: a meta-analysis of outcome studies. Psychiatr Serv. 2012;63(10):963–973. PubMed CrossRef

- Hojat M, DeSantis J, Shannon SC, et al. The Jefferson Scale of Empathy: a nationwide study of measurement properties, underlying components, latent variable structure, and national norms in medical students. Adv Health Sci Educ Theor Pract. 2018;23(5):899–920. PubMed CrossRef

This PDF is free for all visitors!