Lessons Learned at the Interface of Medicine and Psychiatry

The Psychiatric Consultation Service at Massachusetts General Hospital sees medical and surgical inpatients with comorbid psychiatric symptoms and conditions. During their twice-weekly rounds, Dr Stern and other members of the Consultation Service discuss diagnosis and management of hospitalized patients with complex medical or surgical problems who also demonstrate psychiatric symptoms or conditions. These discussions have given rise to rounds reports that will prove useful for clinicians practicing at the interface of medicine and psychiatry.

Prim Care Companion CNS Disord 2025;27(4):25f03913

Author affiliations are listed at the end of this article.

Have you ever treated or had to evaluate a patient who had made a life-threatening drug overdose (OD) or suicide attempt? Have you been uncertain about what factors would be involved in determining whether they needed a psychiatric hospitalization or care in some other rehabilitative or treatment setting? Have you been troubled by problematic interactions between staff and family members regarding disposition decisions? Have you wondered who would develop long-term sequelae after their suicide attempt? If you have, the following case vignette and discussion should prove useful.

CASE VIGNETTE

Ms A, a 26-year-old woman with severe and recurrent major depressive disorder (MDD) (taking escitalopram 10 mg/day), was brought to the hospital by emergency medical services after an acetaminophen and alcohol OD (in the context of a relationship breakup and losing her job due to her depression). Ms A left a note that conveyed a detailed plan and her intent to die.

In the emergency department (ED), she was confused, had signs of rhabdomyolysis (with a creatine kinase [CK] of 15,000 U/L), and markedly elevated liver enzymes (including an aspartate aminotransferase of 1,200 IU/L and an alanine aminotransferase of 1,100 U/L). Although the exact timing of her OD was unclear, she was treated with N-acetylcysteine to manage her acetaminophen toxicity. As she awoke, she became more coherent and said repeatedly that she wished she had died. She denied having a history of an alcohol or substance use disorder (SUD).

Ms A lives alone and has limited social support aside from her mother, with whom she has a strained but ongoing relationship. She has a history of intermittent engagement in psychiatric care but has struggled with treatment adherence, often discontinuing therapy and medications when her symptoms improved. Given her ongoing wish to die, the intensive care unit (ICU) team placed Ms A on suicide precautions (with a 1:1 observer). Her mother, who was sitting at her bedside, was visibly distressed. A psychiatry consult was called to assess Ms A’s ongoing risk of suicide, address her depression, and determine the level of psychiatric care she would need after becoming medically stable.

DISCUSSION

What Is a Serious Suicide Attempt?

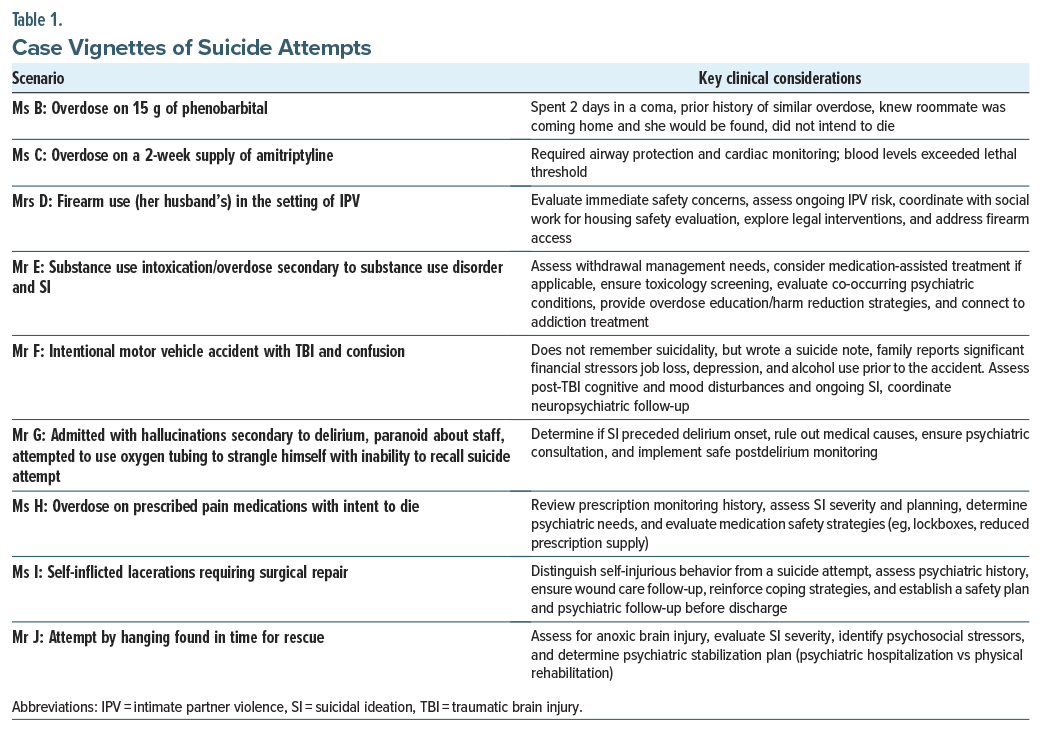

An attempt on one’s life can be considered as serious when there was the intent to die, the consequences of the attempt required medical/surgical care (eg, the attempt required a life-saving intervention), or the blood levels of an ingested agent exceed a certain threshold. Serious suicide attempts often necessitate intensive care, airway protection, cardiac monitoring, or antidotal treatment to counteract the toxic effects of medications (eg, acetaminophen). Methods involving asphyxiation, high-impact trauma, and self-inflicted injuries requiring surgical interventions are also classified as serious suicide attempts. Additional factors include premeditation, steps taken to avoid discovery, and the use of means with high potential for lethality (see Table 1 for additional case vignettes of suicide attempts). Identifying these characteristics is essential for risk stratification and guiding intervention strategies.

Who Is Most Likely to Attempt Suicide?

According to data provided by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention in 2021, suicide was the 11th leading cause of death in the United States and the second leading cause of death in those aged 10–14 and 25–34 years.1 Suicide (the act of intentionally ending one’s life) is a tragic event that leaves grieving loved ones with unanswered questions.

Roughly one-third of those who think about suicide go on to attempt suicide, with approximately 1 person dying by suicide for every 20 individuals who attempt suicide.2 Moreover, the risk of acting on suicidal thoughts tends to increase when thoughts of suicide and the desire to die become more frequent.3 Among 302 individuals who made medically significant suicide attempts, roughly one-third (37%) attempted suicide again during a 5-year follow-up period, and 6.7% died by suicide.4

Those at highest risk for suicide are those with a psychiatric illness (roughly 95%), while serious affective illnesses (MDD and bipolar disorder) account for 50% of individuals who take their own lives, alcohol and SUDs account for 25%, schizophrenia and other psychotic disorders account for 10%, and borderline personality disorder accounts for 5%.5

While individuals with psychiatric disorders are at the highest risk for suicide, severe or chronic medical conditions (eg, acquired immunodeficiency syndrome [AIDS], malignancy, head trauma, epilepsy, and dementia) also predispose to suicide, with those with AIDS having a 3-fold increase in the risk of suicide and those with malignancy having a suicide rate almost twice as great as those in the general population, with the highest rates found within the first 2 years following the diagnosis.5 Overall, medical disorders account for approximately 35%–40% of suicides, and as many as 70% of suicides occur in individuals above the age of 60 years.

While a specific genetic predisposition for suicide has not yet been established, suicide is more common in certain families. Even after controlling for a family’s psychiatric history, there is a 2-fold increase in the risk of suicide in those with a family history of suicide. Whether this risk is mediated by a shared genetic predisposition, psychiatric disorders, impulsive behavior, or shared family environment remains unclear.5

Rates of suicide differ by age, gender, and ethnicity. Individuals older than 65 years are roughly 1.5 times more likely to take their own life than are younger individuals, with white males over the age of 85 years having an even higher suicide rate. In general, 1 out of 4 suicide attempts in the elderly is fatal, attributed to more serious attempts and to less physiological reserve after a suicide attempt.5

While elderly individuals have the highest rates of suicide, suicide rates among young adults (between ages 15 and 24 years old) have roughly tripled over recent decades, with suicide being the second leading cause of death in those aged 15–24 year in the United States as of 2022.5 Native Americans and white people attempt, and die from, suicide more than those from other races, with African American and Hispanic individuals having approximately half the suicide rates of white people.5

Suicide is also more common among men (ie, because they use more lethal means), although women attempt suicide more often than do men. Those who have never married, who are unemployed, who are under financial stress, or who have terminal illness are at increased risk, as are those with a family history of suicide. Furthermore, half of those who take their own life have already made an unsuccessful attempt.5

Roughly half of the individuals who take their own life have had contact with their primary care provider (PCP) within the month before their death, and approximately three-fourths of people who died by suicide had seen their PCP during the year before their death. Given that a history of attempted suicide is one of the most potent risk factors for suicide, a thorough and systematic suicide risk assessment should be performed after someone has made a suicide attempt.

Which Factors Predispose or Protect Against Suicide?

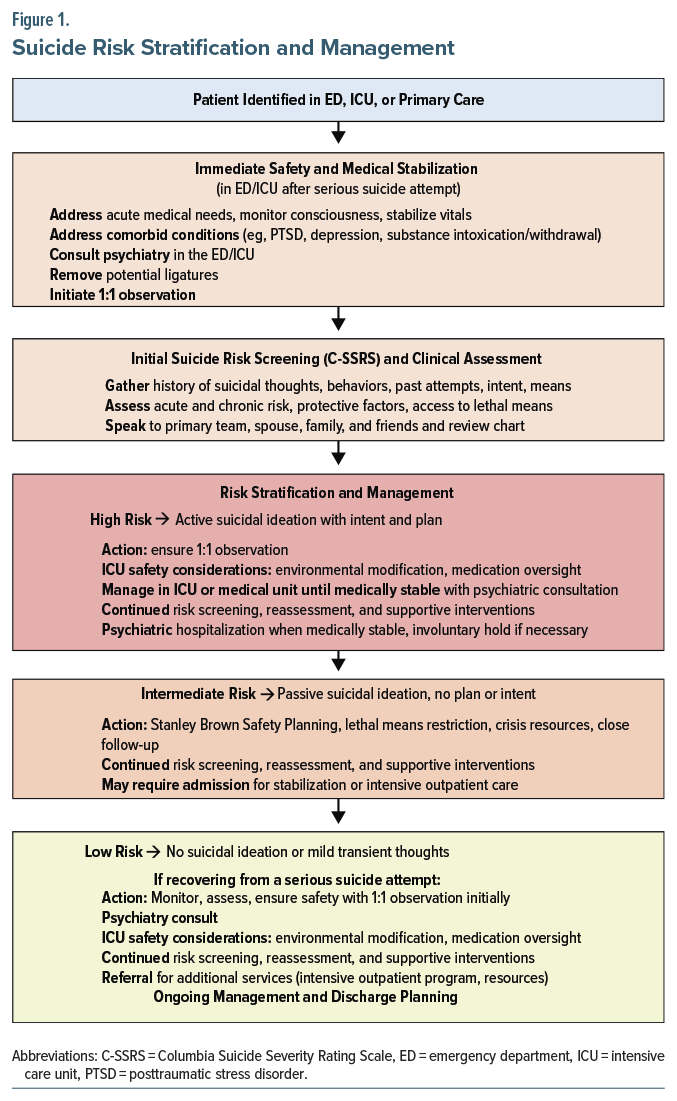

Suicide risk assessments evaluate an individual’s acute and chronic risk factors, protective factors, and precipitants to determine overall risk level (eg, low, moderate, and high) and guide targeted intervention strategies (see Figure 1 for a flowchart on suicide risk assessment).5 A comprehensive suicide risk assessment should go beyond identifying risk factors—it must clarify why an individual is experiencing suicidality now and how modifiable factors can be addressed to reduce imminent risk. While suicide screening tools are commonly used, they often focus on static risk factors rather than actionable areas for intervention.

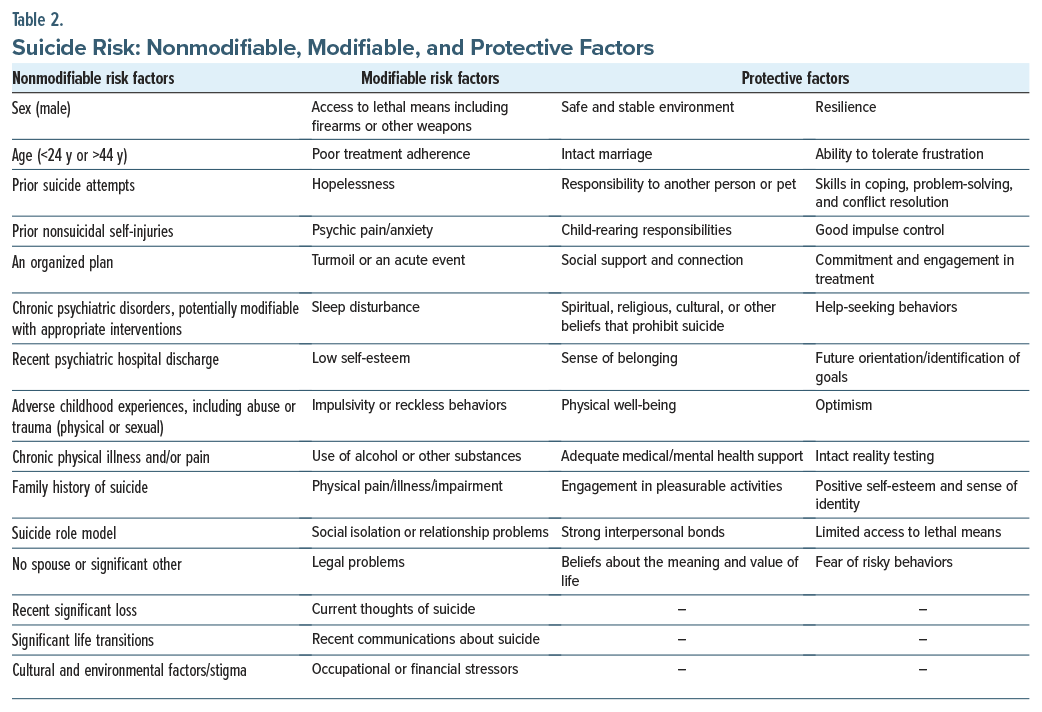

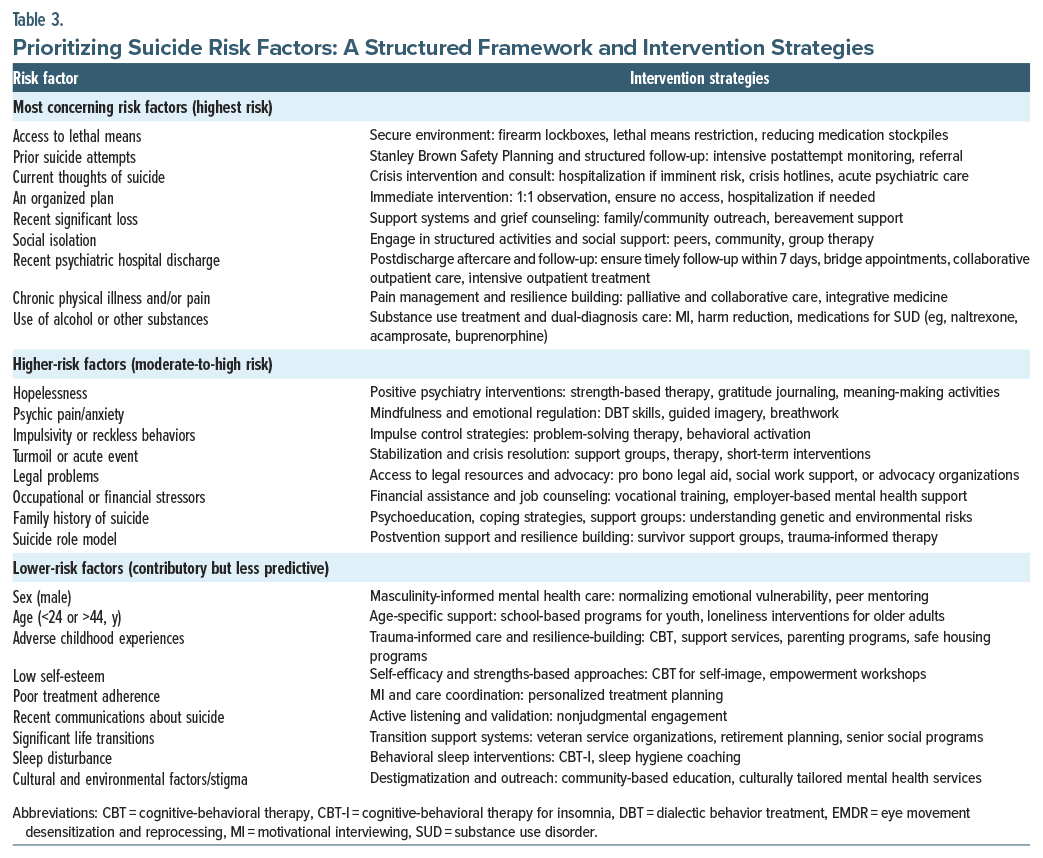

Suicide risk factors can be categorized as modifiable or nonmodifiable and acute or chronic (see Table 2 for suicide risk factors and protective factors). While nonmodifiable risk factors (eg, male sex, age, prior suicide attempts, family history) contribute to baseline vulnerability, modifiable factors, including access to lethal means, untreated psychiatric symptoms, hopelessness, sleep disturbance, substance use, and social isolation, drive imminent risk and require proactive intervention. To bridge the gap between assessment and action, Table 3 provides a structured, risk-stratified approach to suicide prevention. High-priority risks (eg, recent suicidal intent, access to lethal means) require immediate intervention, while moderate and lower-priority risks warrant tailored support services and long-term management (see Table 3).

Protective factors against suicide include effective coping skills, problem-solving abilities, cultural identity, and reason to live (see Table 2). Family support, social connectedness, and access to community resources further buffer risk, while societal factors (eg, moral/ religious objections to suicide, restricting of lethal means) remain essential.6 The goal of assessing protective factors is to reinforce resilience and connect individuals with appropriate mental health and community-based support.

Risk assessments must balance chronic and acute risk factors. An individual with prior suicide attempts but no current suicidal thoughts may have low imminent risk but moderate chronic risk. However, acute distress, such as loss of a partner or major life stressors, can rapidly escalate risk, underscoring the importance of clinical judgment in risk stratification and targeted intervention.7

How Are Individuals Who Have Made a Serious Suicide Attempt Managed in Critical Care Units and on General Medical and Surgical Floors?

Psychological treatments in medical-surgical settings are often limited, yet early psychotherapeutic interventions have been developed for those who survive a serious suicide attempt.8 The Suicide Attempt Multicomponent Intervention Treatment is an inpatient psychotherapy program designed for patients hospitalized in medical units following a medically serious suicide attempt. It consists of 8 individual psychotherapy sessions, combining dialectical behavioral, mentalization-based, and narrative therapies, with the goal of reducing the risk of suicide reattempts, enhancing coping strategies, and addressing psychological distress prior to discharge.8

In critical care settings, engagement in psychological interventions is often complicated by delirium, sedation, and communication barriers from intubation. Engaging in psychological interventions is often problematic. Nevertheless, assessment of emotional responses to surviving a suicide attempt can provide insight into ongoing suicidal intent and facilitate support interventions.9 Medical and surgical sequelae of serious attempts frequently exacerbate distress. Spiritual care consultations for patients who identify as religious or spiritual may help alleviate this distress.

A comprehensive social history helps identify suicide risk factors (eg, loneliness, intimate partner violence, housing instability, and lack of support). Collaboration with social workers and families can strengthen protective networks, while trauma-informed care should be used for individuals with a history of trauma. Firearm access and other lethal means must be assessed to reduce further risk (see Table 3 and Figure 1 for additional risk prioritization and intervention strategies). Law enforcement may be involved in emergency responses to suicide attempts that intersect with legal concerns, substance use, firearm-related incidents, or attempted murder-suicide, where medical teams must navigate complex ethical and legal dynamics while ensuring safe transport and appropriate management, including cases where the patient is under arrest.

Suicide assessments among critically ill individuals are often complicated by difficulties in communication (eg, associated with intubation that was required for airway protection and which prevents them from speaking). In addition, sedation often interferes with consciousness and attention, making clarity of thought problematic. Moreover, life-saving care typically disrupts sleep cycles and interferes with empathic interviews and assessments.10

Delirium, comprised of disordered affect, behavior, and cognition, also interferes with the ability to appreciate and manipulate information and make decisions. Further, memory impairments (affecting immediate, recent, and remote recall) can hinder the ability to obtain an accurate history.10,11

Medications, including psychotropics, replete with side effects can pose challenges in critically ill individuals (eg, promoting drug-drug interactions).10 In ICU settings, medication administration for actively suicidal patients requires close monitoring and precautions to ensure safety. There may be concerns about “cheeking” or hoarding pills in furtherance of a future suicide attempt. To mitigate these risks, oral medications should be administered under direct observation to ensure that they are swallowed. Alternatively, intravenous (IV) medications may be more appropriate when available and clinically appropriate, as they deliver medications reliably.

Those who regain consciousness in the ICU after a suicide attempt often experience despair (at the realization that they are still alive), shame (regarding their actions and the burdens they placed on loved ones), guilt (over the pain and anxiety they caused family and friends), fear (of judgments held by others), and dismay (at the possibility of long-term medical complications that they may face due to their actions).10 Some individuals are ambivalent about surviving their suicide attempt (eg, feeling relief, disappointment, and/or anger that their attempt failed knowing that their problems remain unresolved).10

Following a serious suicide attempt, patients in critical care settings may be unable to provide informed consent due to several factors (eg, intubation, sedation, or delirium). Emergency medical treatment should proceed without delay while awaiting a comprehensive evaluation by a psychiatrist. When available, advance directives or input from a health care proxy may guide urgent medical decisions. If further interventions are required and the patient is able, informed consent should be sought whenever possible. However, when there are concerns about impaired decision-making capacity due to delirium, depression, or persistent thoughts of suicide, an urgent capacity assessment by a consultation psychiatrist is essential.

The intensity and pervasiveness of emotions following a serious suicide attempt vary widely. Some individuals are withdrawn and remain unwilling to engage in interviews, while others readily convey their feelings and seek support from staff.10,12

Health care professionals should approach survivors of a serious suicide attempt with an empathic and respectful approach, listening closely to what the patient is communicating.10

What Do Suicide Precautions Entail in Settings Filled With Lines, Tubes, and Sharp Objects?

Suicide risk assessment begins even before a patient arrives at the ED and continues throughout their stay. Patients at risk must be protected until they are no longer at imminent risk. Common precautions include 1:1 observation, removal of potentially dangerous objects or medications, and restraints as a last resort, with ongoing reassessment and documentation.13

No-harm or safety contracts are no longer considered acceptable and do not prevent suicide or remove provider liability.13 Instead, structured interventions, such as Crisis Response Plans and Safety Planning Interventions, focus on concrete skills and strategies to reduce risk and can be implemented in both psychiatric and medical settings.13

Medical and surgical floors present unique challenges, as essential equipment (eg, IV tubing, oxygen lines, monitoring devices) cannot be removed. Unlike psychiatric units, which are designed to be ligature-resistant, critical care settings require a balance between medical care and risk mitigation. The American Psychiatric Association and the Joint Commission provide guidelines for suicide precautions in general hospitals, emphasizing the need for 1:1 monitoring, with trained staff or 360-degree video surveillance as alternatives.14–16 Efforts should focus on removing obvious hazards (eg, eating utensils, corded phones) while maintaining appropriate medical care. Monitoring should continue during sleep and restroom use, and visitors, incoming items, and personal belongings should be screened for potential risks.15

ICUs pose additional risks, as most essential medical equipment and supplies can serve as a means for self-harm.10 Maintaining suicide precautions in these settings requires interdisciplinary collaboration among nurses, physicians, and psychiatric consultants to monitor behavior, remove potential hazards, and interpret suicidal statements in context.10 While 1:1 nursing care is ideal, when staffing is limited, sitters or covering staff should be used, with restraints as a last resort.10,17 Ultimately, the goal of suicide precautions is to foster a safe and supportive environment that promotes recovery while ensuring essential medical care.

What If a Patient Does Not Remember Making a Suicide Attempt?

If a patient does not remember their suicide attempt, this warrants a careful evaluation by a psychiatrist. Potential contributing factors (eg, delirium, intoxication, traumatic brain injury [TBI], hypoxia, medication side effects) should be thoroughly assessed. A comprehensive psychiatric evaluation is crucial to identify ongoing risk factors. Collateral information from first responders, ED records, nursing and critical care staff, family, or loved ones can provide valuable context and help inform safety planning and treatment.

What Type of Treatment Is Indicated After a Serious Suicide Attempt?

Following a serious suicide attempt, the primary goal is medical stabilization, followed by assessing the reasons for the attempt and the risk of further harm. Given the strong association between suicidality, suicide attempts, and mental health conditions, evaluation includes diagnostic clarification and psychiatric treatment planning, with recommendations for the most appropriate level of care.18–21 The goal is to identify the least restrictive setting where a patient can be managed safely, minimizing coercion and undue restrictions on their freedom of movement and privacy. Repeat evaluations often refine treatment recommendations, as the psychiatric history is clarified over the course of the medical admission.

A locked inpatient psychiatric admission is generally indicated for those who remain suicidal, particularly if they endorse a plan, have persistent intent, have unmanageable urges to harm themselves, pose a threat to others, or demonstrate severely impaired judgment in the context of a mental illness that interferes with their ability to remain safe in the community. High lethality attempts, a low probability of rescue, premeditation, or disappointment at survival raise additional “red flags.”22 However, hospitalization may be counterproductive in chronically suicidal patients, lead to worse outcomes, and reinforce a pattern of self-injury, as seen in patients with borderline personality organization.23 In general, acute psychiatric hospitalization should be viewed as a time-limited intervention aimed at stabilizing the crisis, rather than as indefinite confinement.

Some patients without acute intent or plan may still benefit from voluntary inpatient psychiatric care, particularly if they have impairments that limit their ability to engage in self-care or follow through with outpatient treatment.22 Lack of social supports, primary care, transportation, or insurance can further complicate outpatient care access. If effective treatment is not feasible in a less restrictive setting, a psychiatric admission may be warranted. In studies of ED patients, hospitalization following a suicide was recommended in only 25%–50% of cases.24,25

In weighing the risks and benefits of various treatment settings, health care providers should consider patient preferences and the potential disruption of hospitalization, especially an involuntary admission. While involuntary admissions may lead to a comparable degree of improvement in social functioning and rates of treatment adherence (including follow-up care), other studies note they lead to lower treatment satisfaction and higher perceptions of coercion.26,27 Some argue that involuntary hospitalizations fail to protect against suicide and that any type of hospitalization is associated with trauma.26 A negative experience may preclude the formation of a therapeutic alliance and lead some patients to avoid seeking future psychiatric care. Further, an unexpected hospitalization can disrupt employment, education, and financial stability, exacerbating depression and hopelessness.

Patients may also have competing needs for psychiatric treatment and inpatient physical rehabilitation due to prolonged critical illness or extensive physical trauma. Some facilities integrate psychiatric care within rehabilitation settings, while others require separate treatment paths. Patients who engage with consultation-liaison (C-L) psychiatry during medical recovery on a medical or surgical unit often show improvement in psychiatric symptoms and may continue transition to outpatient care without requiring inpatient psychiatric admission. Patients who have pronounced psychiatric symptoms coupled with ongoing medical needs that cannot be met on a psychiatric unit may need to remain on the medical or surgical unit, with ongoing treatment by the psychiatric consultation team.

What Happens to Patients in the Aftermath of a Serious Suicide Attempt and After 1 Year?

The morbidity and mortality rates after a suicide attempt vary depending on the method used and the patient’s characteristics. According to a 2022 meta-analysis, suicide attempts involving a firearm were lethal 90% of the time, hanging and suffocation in 85%, jumping from height in 47%, drug ingestion in 8%, and cutting in 4%.28 However, these figures likely do not match the experience of critical care providers, as a significant proportion of individuals who attempt suicide die before they can be transported to the hospital. Once an individual has been transported and admitted to a hospital, their chances of surviving are substantially improved. For example, in a study of 11 consecutive cases of self-inflicted gunshot wounds to the head who were admitted to Harborview Medical Center, 10 were still alive at follow-up 11 months after their injury.29 The patient’s age, medical comorbidities, and, in some studies, gender also mediate the likelihood of dying.

Evaluating a patient’s prognosis after a serious suicide attempt must account for survival and the chances of a meaningful recovery. However, the interaction of the method employed and patient characteristics makes the outcome of any specific case difficult to predict. For instance, of the 10 individuals who survived in Kriet and colleagues’29 study, 3 recovered completely, 6 experienced modest chronic deficits (eg, expressive aphasia and anosmia), and 1 developed a moderate cognitive impairment. Understanding the mechanism of the injury offers the best opportunity to make an accurate prediction. Gunshot wounds cause a variety of injuries and TBIs; hanging can cause hypoxia and hypoperfusion of the central nervous system; jumping from a height can result in orthopedic and spine injuries and TBI; and drug ingestions may cause hypoxia, hypotension, arrhythmia, or other outcomes depending on the substance(s) consumed. Neuroprognostication involves significant uncertainty, and the recovery trajectory of TBIs often extends beyond 1 year.30

In addition to recovery from physical injuries, patient outcomes are also driven by their psychiatric sequelae and the risk of a repeat attempt. Many studies have found an increased risk of taking one’s own life among those who have attempted suicide, while those who have a history of medically serious or violent suicide attempts have an even higher risk of attempting suicide again. In a 10-month follow-up study of patients admitted to a critical care unit following a serious OD, Koh and colleagues noted that 5% died by suicide, and an additional 42% were readmitted after another nonfatal attempt.5 Studies in international settings across several decades have reported similarly elevated risks after a medically serious suicide attempt.4 Moreover, the overall mortality from other causes is also elevated after a serious suicide attempt, possibly associated with older age and chronic illness.31

Psychiatric diagnoses and SUDs also mediate suicide risk, with borderline personality disorder and alcohol use disorder both associated with higher rates of another attempt at suicide.31 Opioid use disorder is another significant factor, but the difficulty in determining the intent behind fatal ODs makes it more challenging to quantify. Finally, it is important to note that suicide attempts predict a more severe trajectory for patients with mood disorders. Individuals with MDD and a prior attempt have a longer duration of illness and a greater number of depressive episodes, as well as higher rates of comorbid anxiety.32

What Does Civil Commitment Entail?

Each state has its own process through which health care providers (eg, psychiatrists, psychologists, internists, nurse practitioners), or, as occurs in some states, judges or police officers can pursue civil commitment, the specifics of which are beyond the scope of this article.33,34 However, despite the differences between criteria for commitment among states, the civil commitment process in all states is based largely on the legal principles of parens patriae and police powers. Parens patriae refers to the government’s responsibility to intervene on behalf of citizens who cannot act in their own best interests, while police power refers to the state’s duty to protect the interests of its citizens.35 Although patients with psychiatric illnesses have been hospitalized since the 1400s, the modern basis for civil commitment emerged in the 1960s–1970s when the focus of interventions shifted from providing asylum toward addressing dangerousness.35

At present, to satisfy the requirements for civil commitment, an individual must have a psychiatric illness and pose an imminent threat to their own safety or to that of others or be so gravely disabled that they cannot provide the necessities for their survival. In those who have made a suicide attempt that requires hospital-level care, this requirement for imminent dangerousness is almost always reached.35 When a patient is civilly committed, they are not allowed to leave the hospital, and attempts to leave warrant involvement of hospital security or local law enforcement to maintain the patient’s safety.

How Can the Assessment of Suicide Risk Be Monitored Throughout a Hospitalization?

Assessment of suicide risk often begins with the use of screening tools, eg, the Columbia Suicide Severity Rating Scale (C-SSRS), which serves as a valuable starting point for those less comfortable with suicide risk assessment. The C-SSRS is designed to quantify the spectrum of suicidal ideation (SI) and behavior and distinguish between suicidality and nonsuicidal self-injurious behavior. Analyses have shown this tool to have a high sensitivity and specificity for suicidal behavior, with the 2 highest levels of severity, suicidal intent and suicidal intent with a plan, being correlated with higher risk for attempting suicide.36

During a hospitalization, especially a prolonged one, the use of evidence-based screening and assessment tools (eg, the C-SSRS and Safe-T) should be performed regularly, and a plan for suicide risk mitigation should be explicitly documented in the medical record.16 Most often, the risk mediation plan ultimately involves transfer to an inpatient psychiatry unit; however, this may not always be the most appropriate option given the severity of a patient’s medical needs.

Most individuals who have been admitted to a hospital following a suicide attempt are likely to be categorized as being at high risk for suicide based on these metrics.36 In the absence of medical needs, such an individual will be transferred to an inpatient psychiatric unit for acute and ongoing management, with the goal of treatment being to mitigate the risk of suicide. Most patients are offered a voluntary hospitalization; however, should they decline, they are appropriate for civil commitment (ie, involuntary hospitalization).

How Might Medical and Surgical Staff React to a Person Who Has Made a Serious Suicide Attempt?

Medical-surgical nurses who care for individuals following a serious suicide attempt may face internal conflicts as they confront their anxiety surrounding the possibility that their patient might die in the hospital.37 Other emotions (eg, pity, sympathy) may be experienced or they may feel annoyed or overwhelmed by having to care for someone who did not care enough about their own life.37 Reactions by staff are shaped by myriad factors (eg, their religious beliefs, personal experiences with suicide), as well as by a patient’s behaviors on the medical-surgical ward.

All patients benefit from feeling valued and empowered by their health care team. Negative responses (eg, anger, frustration, anxiety, or fear) can cause a patient to feel worthlessness, which might have contributed to their suicide attempt. C-L psychiatrists can support team members and provide opportunities for reflection when managing psychologically intense cases; this can help staff face insecurity, isolation, or demoralization generated while caring for these individuals.

How Might Family Members React to the News of a Serious Suicide Attempt?

Family members often take on multiple roles following a serious suicide attempt, including advocates, caregivers, and surrogate decision-makers when the patient lacks capacity. Their reactions vary based on their relationship to the patient, proximity to the event, and whether they directly witnessed the attempt. The trauma of finding a loved one seriously injured can compound feelings of shock, grief, guilt, and uncertainty.38

Financial stressors, job disruptions, marital strain, and withdrawal from usual sources of meaning and support further intensify emotional distress.39 Critical illness may trigger sadness, anger, and fear, and suicide attempts often raise questions about whether the event could have been predicted or prevented. In the aftermath, family members frequently report distress, anxiety, insomnia, depression, SI, and anger, and many express a strong need for information and reassurance from the medical team.40,41

Repeat suicide attempts, particularly those occurring soon after hospitalization, can heighten family distress and may be perceived as a rejection of care. While these situations often stem from persistent suicidality, untreated psychiatric illness, or lack of protective factors, families may react with frustration, fear, or even mistrust of the treatment process. Education on suicide risk trajectories, the likelihood for future attempts, and the potential for clustering within families is essential.42 Given the high emotional and practical burdens placed upon the family, treatment teams must prioritize family support, provide psychoeducation, and facilitate access to community resources.

How Might a Person React to Surviving a Serious Suicide Attempt?

A patient’s reaction to surviving a serious suicide attempt is typically influenced by the emotions and precipitants that led to the attempt. One method of assessing the intent and seriousness of an attempt is to embark upon a “psychological autopsy” that gathers information (from family members, therapists, psychiatrists, or suicide notes) and generates a timeline of events, psychological states, warning signs, and potential intervention points, which could have interrupted the self-destructive thought process. While this strategy can help to identify early indicators of suicidal thinking, it has limitations, as the reactions of family, friends, and caregivers (eg, guilt, self-blame) may skew the reliability of the information received. Similarly, when examining the psychological state of individuals who have survived a serious suicide attempt, the most distressing symptoms prior to the attempt often include depressed mood, hopelessness, desperation, and emptiness.43 Frequent themes in such cases include being alive by accident, losing the fear of death, regretting survival, and considering the impact of the suicide attempt on relationships with loved ones.

In addition, individuals who wished they had died from their suicide attempt often endorse higher levels of depression, hopelessness, and suicidal intent and are more likely to die by suicide later in life, compared to those who are glad to be alive or who are ambivalent about having survived.44 These reactions are crucial to unearth, as they can be assessed and modified through therapeutic interventions, thereby decreasing the risk of future suicide attempts and death.

Where Can Patients and Providers Obtain Specialty Consultation, Support, and Treatment?

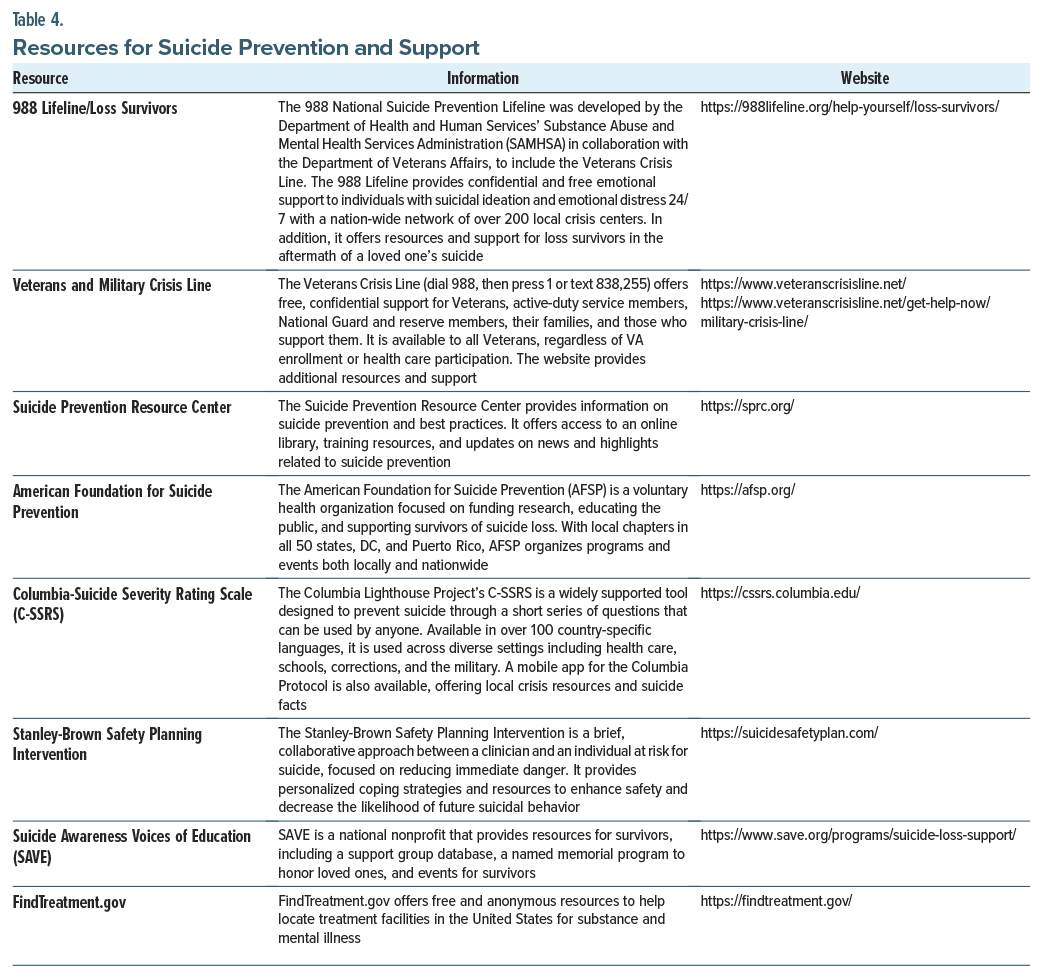

PCPs play a critical role in long-term suicide prevention by monitoring risk factors, ensuring treatment adherence, and coordinating psychiatric care following hospital discharge. Given that many individuals who die by suicide have had recent contact with their PCP, integrating structured risk assessments and follow-up care is essential. Providers can refer to Table 3 for risk stratification and intervention planning and Table 4 for additional resources on suicide prevention, support services, and treatment access. These resources provide support for patients, clinicians, and family members who encounter issues related to suicide.

What Happened to Ms A?

Over the course of several days, Ms A’s liver function and renal function gradually improved, and her CK and creatinine levels decreased. Although Ms A was transferred from the ICU to a regular medical unit, her psychological outlook remained concerning. She continued to express passive SI (ie, the wish to be dead), yet she acknowledged the need for further psychiatric care. Ms A was seen daily by a psychiatrist for supportive therapy, while family interventions were provided by a social worker. Ms A was placed on a Section 12 (legal hold) due to ongoing concerns about making another attempt; however, she agreed to be transferred to an inpatient psychiatric unit for additional treatment (including therapy and medication) until her depression and coping skills improved.

CONCLUSIONS

Serious suicide attempts are those in which there was the intent to die, the consequences of the attempt required live-saving medical/surgical care, or the blood levels of an ingested agent exceeded a certain threshold. While individuals with psychiatric disorders are at the highest risk for suicide, severe or chronic medical conditions also predispose to suicide.

Suicide assessments seek to identify risk factors, especially modifiable ones, which can be altered to reduce the risk of suicide. Modifiable risk factors can be acute or chronic and include access to lethal means, treatment adherence, hopelessness, psychic pain/anxiety, sleep disturbance, recent turmoil, low self-esteem, impulsive and reckless behavior, use of alcohol or other substances, physical pain/illness/impairment, social isolation or relationship problems, legal problems, current thoughts about suicide, and occupational or financial stressors. Assessment of the patient’s social history is key to identifying risk factors for suicide (eg, loneliness, intimate partner violence, housing instability, unemployment, and lack of social support). Suicide assessments among critically ill individuals are often complicated by difficulties in communication (eg, associated with intubation that was required for airway protection, and which prevents them from speaking). In addition, exogenous sedation often interferes with consciousness and attention, making clarity of thought problematic.

The evaluation of suicide risk (eg, gathering information about thoughts of suicide, plans for suicide, the intent to commit suicide, past attempts at suicide, the precipitants for suicide, a family history of suicide, premeditation or impulsivity linked with an attempt, the risks associated with an attempt, and the opportunities for being rescued) often begins even before a patient has arrived at the ED. However, even repeated suicide assessments often fail to identify why an individual is making, or has made, an attempt and why the individual is entertaining that action now as a solution to their problems.

Those who regain consciousness in the ICU after a suicide attempt often experience despair (at the realization that they are still alive), shame (regarding their actions and the burdens they placed on loved ones), guilt (over the pain and anxiety they caused family and friends), fear (of judgments held by others), and dismay (at the possibility of long-term medical complications that they may face due to their actions).

Article Information

Published Online: July 8, 2025. https://doi.org/10.4088/PCC.25f03913

© 2025 Physicians Postgraduate Press, Inc.

Submitted: December 31, 2024; accepted March 31, 2025.

To Cite: Matta SE, Dietrich E, Fedotova N, et al. Serious suicide attempts: assessment and management. Prim Care Companion CNS Disord 2025;27(4):25f03913.

Author Affiliations: Department of Psychiatry, Massachusetts General Hospital, Harvard Medical School, Boston, Massachusetts (Matta, Stern, Fedotova); Harvard University, Cambridge, Massachusetts (Dietrich); Brigham and Women’s Hospital, Boston, Massachusetts (Dietrich, Fedotova); Lewis Gale Medical Center in Salem, Salem, Virginia (Braford); Department of Psychiatry, University of Texas Southwestern Medical Center, Dallas, Texas (deVries); ChristianaCare, Wilmington, Delaware (DiAngelo); Psychiatry and Behavioral Health, Stanford Health Care, Stanford, California (Hoover).

Corresponding Author: Sofia E. Matta, MD, Department of Psychiatry, Massachusetts General Hospital, Harvard Medical School, 55 Fruit St, Boston, MA 02114 ([email protected]).

Relevant Financial Relationships: None.

Funding/Support: None.

Clinical Points

- Approximately half of the individuals who take their own life have had contact with their primary care provider within the month before their death.

- Assessments of suicide risk are based upon clinical judgment, ie, a distillation of the individual’s interpersonal, situational, clinical, and demographic factors that may increase or decrease one’s risk of suicide. Unfortunately, many health care facilities now rely solely on the answers to brief screening questions (eg, the Columbia Suicide Severity Rating Scale) to determine whether a person is safe.

- All patients considered at risk for suicide must be protected until the evaluating clinician determines that the patient is not at imminent risk of self-injury and suicide.

- The least restrictive method that provides for the safety of the patient should be employed, the method(s) chosen should be effective, and the rationale for their use should be documented in the medical record.

- Although states differ in their criteria for civil commitment, most states require that an individual must have a psychiatric illness and pose an imminent threat to their own safety or to that of others or be so gravely disabled that they cannot provide the necessities for their survival.

- Reactions by staff to those who have made a serious suicide attempt are shaped by myriad factors (eg, their religious beliefs and personal experiences with suicide) as well as by a patient’s behaviors on the medical-surgical ward.

References (44)

- Suicide. National Institute of Mental Health (NIMH). Accessed November 9, 2024. https://www.nimh.nih.gov/health/statistics/suicide#part_2561

- Nock MK, Borges G, Bromet EJ, et al. Cross-national prevalence and risk factors for suicidal ideation, plans and attempts. Br J Psychiatry. 2008;192(2):98–105. PubMed CrossRef

- Turecki G, Brent DA, Gunnell D, et al. Suicide and suicide risk. Nat Rev Dis Primers. 2019;5(1):74. PubMed CrossRef

- Beautrais AL. Further suicidal behavior among medically serious suicide attempters. Suicide Life Threat Behav. 2004;34(1):1–11. PubMed CrossRef

- Koh KA, Donovan AL, Bird SA, et al. Care of the patient with thoughts of suicide. In: Stern TA, Beach SR, Smith FA, et al, eds. Massachusetts General Hospital Handbook of General Hospital Psychiatry. 8th ed. Elsevier;2025:740–753.

- CDC. Risk and protective factors for suicide. Suicide Prevention. CDC; 2024. Accessed December 3, 2024. https://www.cdc.gov/suicide/risk-factors/index.html

- Fowler JC. Suicide risk assessment in clinical practice: pragmatic guidelines for imperfect assessments. Psychotherapy. 2012;49(1):81–90. PubMed CrossRef

- Beneria A, Motger-Albertí A, Quesada-Franco M, et al. A Suicide Attempt Multicomponent Intervention Treatment (SAMIT Program): study protocol for a multicentric randomised controlled trial. BMC Psychiatry. 2024;24(1):666. PubMed CrossRef

- Wolk-Wasserman D. The intensive care unit and the suicide attempt patient. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 1985;71(6):581–595. PubMed CrossRef

- Garcia RM. Psychiatric disorders and suicidality in the intensive care unit. Crit Care Clin. 2017;33(3):635–647. PubMed CrossRef

- Maldonado JR. Delirium pathophysiology: an updated hypothesis of the etiology of acute brain failure. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2018;33(11):1428–1457. PubMed CrossRef

- Darnell D, Pierson A, Whitney JD, et al. Acute and intensive care nurses’ perspectives on suicide prevention with medically hospitalized patients: exploring barriers, facilitators, interests, and training opportunities. J Adv Nurs. 2023;79(9):3351–3369. PubMed CrossRef

- Rozek DC, Tyler H, Fina BA, et al. Suicide intervention practices: what is being used by mental health clinicians and mental health allies? Arch Suicide Res. 2023;27(3):1034–1046. PubMed CrossRef

- Jacobs D, Baldessarini R, Conwell Y, et al. Practice guideline for the assessment and treatment of patients with suicidal behaviors. Psychiatry Online. 2003. Accessed December 16, 2024. https://psychiatryonline.org/pb/assets/raw/sitewide/practice_guidelines/guidelines/suicide-1410197760903.pdf

- Special report: suicide prevention in health care settings. The Official Newsl Jt Comm. 2017;37(11), 1–6. Accessed December 16, 2024. https://www.org/-/media/tjc/documents/resources/patient-safety-topics/suicide-prevention/november_perspectives_suicide_risk_reduction.pdf

- National Patient Safety Goal for Suicide Prevention. R3 Report (18). 2018. Accessed December 16, 2024. https://www.jointcommission.org/-/media/tjc/documents/standards/r3-reports/r3_18_suicide_prevention_hap_bhc_cah_11_4_19_final1.pdf

- Le A. Identification and mitigation of environmental hazards in psychiatric patient suicide prevention: a review. In: University of California San Francisco (Ed). DNP Qualifying Manuscripts; 2021. 31.

- Bachmann S. Epidemiology of suicide and the psychiatric perspective. Int J Environ Res Publ Health. 2018;15(7):1425. PubMed CrossRef

- Ferrari AJ, Norman RE, Freedman G, et al. The burden attributable to mental and substance use disorders as risk factors for suicide: findings from the Global Burden of Disease Study 2010. PLoS One. 2014;9(4):e91936. PubMed CrossRef

- Harris EC, Barraclough B. Suicide as an outcome for mental disorders: a meta-analysis. Br J Psychiatry. 1997;170(3):205–228. PubMed CrossRef

- Yeh H-H, Westphal J, Hu Y, et al. Diagnosed mental health conditions and risk of suicide mortality. Psychiatr Serv. 2019;70(9):750–757. PubMed CrossRef

- American Psychiatric Association. Practice Guideline for the Assessment and Treatment of Patients With Suicidal Behaviors. American Psychiatric Association; 2003.

- Goodman M, Roiff T, Oakes AH, et al. Suicidal risk and management in borderline personality disorder. Curr Psychiatry Rep. 2012;14(1):79–85. PubMed CrossRef

- Hepp U, Moergeli H, Trier SN, et al. Attempted suicide: factors leading to hospitalization. Can J Psychiatry. 2004;49(11):736–742. PubMed CrossRef

- Suominen K, Lönnqvist J. Determinants of psychiatric hospitalization after attempted suicide. Gen Hosp Psychiatry. 2006;28(5):424–430. PubMed CrossRef

- Corderoy A, Kisely S, Zirnsak T, et al. The benefits and harms of inpatient involuntary psychiatric treatment: a scoping review. Psychiatry Psychol L. 2024. doi:10.1080/13218719.2024.2346734 CrossRef

- Kallert TW, Glöckner M, Schützwohl M. Involuntary vs. voluntary hospital admission: a systematic literature review on outcome diversity. Eur Arch Psychiatry Clin Neurosci. 2008;258(4):195–209. PubMed CrossRef

- Cai Z, Junus A, Chang Q, et al. The lethality of suicide methods: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Affect Disord. 2022;300:121–129. PubMed CrossRef

- Kriet JD, Stanley RB, Grady MS. Self-inflicted submental and transoral gunshot wounds that produce nonfatal brain injuries: management and prognosis that produce nonfatal brain injuries: management and prognosis. J Neurosurg. 2005;102(6):1029–1032. PubMed CrossRef

- Fischer D, Edlow BL, Giacino JT, et al. Neuroprognostication: a conceptual framework. Nat Rev Neurol. 2022;18(7):419–427. PubMed CrossRef

- Hirot F, Ali A, Azouvi P, et al. Five-year mortality after hospitalisation for suicide attempt with a violent method. J Psychosom Res. 2022;159:110949. PubMed CrossRef

- Kim SW, Stewart R, Kim JM, et al. Relationship between a history of a suicide attempt and treatment outcomes in patients with depression. J Clin Psychopharmacol. 2011;31(4):449–456. PubMed CrossRef

- Brendel R, Schouten R, Nesbit A, et al. Legal and ethical issues. In: Levenson JL, ed. Textbook of Psychosomatic Medicine and Consultation-Liaison Psychiatry 2019. American Psychiatric Association Publishing; 2019. 42–42.

- Johnson JM, Stern TA. Involuntary hospitalization of primary care patients. Prim Care Companion CNS Disord. 2014;16(3):PCC.13f01613. PubMed

- Testa M, West SG. Civil commitment in the United States. Psychiatry. 2010;7(10):30–40. PubMed

- Posner K, Brown GK, Stanley B, et al. The Columbia-Suicide Severity Rating Scale: initial validity and internal consistency findings from three multisite studies with adolescents and adults. Am J Psychiatry. 2011;168(12):1266–1277. PubMed CrossRef

- Lyu XC, Chen C, Lee LH, et al. Dealing with a stressful extra duty: the intrapersonal conflict experiences of nurses caring for survivors of suicide attempts on medical-surgical wards. Int J Ment Health Nurs. 2024;33(6):2170–2179. PubMed CrossRef

- Varghese R, Patel K, Burke H, et al. Challenging a surrogate decision-maker: a case of an incapacitated patient following self-enucleation. Prim Care Companion CNS Disord. 2022;24(3):21f03102. PubMed CrossRef

- Ferrey AE, Hughes ND, Simkin S, et al. The impact of self-harm by young people on parents and families: a qualitative study. BMJ Open. 2016;6(1):e009631. PubMed CrossRef

- Buus N, Caspersen J, Hansen R, et al. Experiences of parents whose sons or daughters have (had) attempted suicide. J Adv Nurs. 2014;70(4):823–832. PubMed CrossRef

- Wagner BM, Aiken C, Mullaley PM, et al. Parents’ reactions to adolescents’ suicide attempts. JAACAP. 2000;39(4):429–436. PubMed CrossRef

- Jang J, Park SY, Kim YY, et al. Risks of suicide among family members of suicide victims: a nationwide sample of South Korea. Front Psychiatry. 2022;13:995834. PubMed CrossRef

- Tillman JG, Stevens JL, Lewis KC. States of mind preceding a near-lethal suicide attempt: a mixed methods study. Psychoanal Psychol. 2022;39(2):154–164. CrossRef

- Henriques G, Wenzel A, Brown GK, et al. Suicide attempters’ reaction to survival as a risk factor for eventual suicide. Am J Psychiatry. 2005;162(11):2180–2182. PubMed CrossRef

This PDF is free for all visitors!