Abstract

Objective: To examine the prevalence and clinical correlates of suicidal mental imagery among individuals who have attempted suicide in India.

Methods: This cross-sectional study included 63 participants who recently attempted suicide. Assessments included the Mini-International Neuropsychiatric Interview, Version 6, suicidality subscale; Patient Health Questionnaire-9; Beck Suicide Intent Scale; Scale for Assessment of Lethality of Suicide Attempt; and a sociodemographic data questionnaire. Data were collected from June 2023 to April 2024.

Results: The majority of participants were unemployed, educated, unmarried, and from nuclear families and rural backgrounds. Common attempt methods were drug overdose and poisoning. Of the participants, 79.4% reported past mental illness. Suicidal mental imagery was present in 38.1% of participants. Associations were found with female sex, unemployment, past mental illness, and higher depression/suicidality scores.

Conclusions: The relationship between depression, suicidality, and mental imagery suggests that addressing imagery could be important for treatment and prevention.

Prim Care Companion CNS Disord 2026;28(1):25m04071

Author affiliations are listed at the end of this article.

Suicide is a major global public health crisis, claiming ∼700,000 lives annually.1 Defined as a deliberate act with a fatal outcome, its impact extends to families and communities.2 It arises from intersecting biological, psychological, social, and environmental factors.3 In India, suicide rates rose from 9.9 to 12.4 per 100,000 between 2017 and 20224; over 13,000 students died by suicide in 2022 (7.6% of all deaths), and Kerala reports persistently high rates.5 Globally, suicide is a leading cause of death among individuals aged 15–44 years; attempts occur 20–30 times more often than deaths, magnifying the burden of ideation and behavior.6

Beyond biological predispositions, psychosocial factors shape vulnerability,7 spanning despair, impaired problem-solving, and limited coping, alongside stigma, discrimination, and poor access to care.8 Risk concentrates among those with mental illness, prior attempts, chronic physical conditions, isolation, and trauma exposure.9

Mental imagery refers to internally generated sensory representations—akin to a mental movie—of sights, sounds, bodily sensations, actions, and other modalities in the absence of external stimuli.10 We focus on suicidal mental imagery as event-focused internal representations related to self-harm or the suicidal act, considering modality, vividness, controllability/intrusiveness, frequency, timing (chronic vs. proximal), and associated distress. Suicidal mental imagery is highly prevalent among people at risk: ∼75% of those who attempt suicide report such images,11 and the intensity of suicidal thinking correlates with imagery vividness and distress.12 The Interpersonal Psychological Theory and the Integrated Motivational-Volitional Model propose that vividly imagining suicide can amplify ideation and may facilitate progression from contemplation to action by fostering acquired capability.13 Suicidal mental imagery has been noted as a factor distinguishing ideators from attempters.14

Despite its apparent importance, research on suicidal mental imagery among people who attempt suicide in India is scarce; most studies are from Western settings.11,15 Accordingly, this cross-sectional study examines the prevalence and clinical correlates of suicidal mental imagery among individuals who have attempted suicide in India. By characterizing the frequency and clinical burden associated with suicidal mental imagery in this high-risk, under-studied population, we aim to inform risk assessment and guide targeted interventions suited to the Indian context.11,15

METHODS

This was a hospital-based cross-sectional study conducted at a teaching hospital in Kozhikode, India. Participants were recruited using a purposive sampling technique. Data were collected from June 2023 to April 2024.

Study Population and Eligibility Criteria

The study population comprised individuals attending the hospital for psychiatric treatment with a history of attempted suicide within the preceding 6 months, who were aged 12 years and above, and provided informed consent for participation. Exclusion criteria were active psychotic symptoms, significant intellectual disability, organic psychiatric disorders, significant cognitive impairment, or unwillingness to participate.

Sample Size

The sample size was calculated based on a previous study by Lawrence et al that involved 39 participants.11 Using the formula n = 4PQ/d2, where p (prevalence) = 74.36%, q = 100, p = 25.64%, and d (absolute precision) = 11, the calculated sample size was 63.

Study Variables

Sociodemographic variables included age, sex, religion, educational status, marital status, occupational status, family type, socioeconomic status, and domicile. Clinical variables included the presence or absence of suicidal mental imagery, other psychiatric illnesses (eg, psychoses, bipolar disorder, anxiety disorders, alcohol use disorders), history of current suicide attempt, history of suicide attempts, family history of suicide attempts, family history of psychiatric illness, intent of suicide, and lethality of suicide attempts.

Assessment Tools

Proforma for sociodemographic data. A semistructured questionnaire developed for the study was used to collect sociodemographic information.

Patient Health Questionnaire-9. The PHQ-9 is a 9-item self-administered questionnaire, scoring each of the 9 Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fourth Edition (DSM-IV), criteria for depression from 0 (not at all) to 3 (nearly every day).16 The Malayalam version was utilized.

Mini-International Neuropsychiatric Interview, Version 6. The MINI is a short, diagnostic structured interview based on DSM-IV criteria, known for its good sensitivity, specificity, interrater reliability, and test-retest reliability. The Malayalam version was utilized, specifically its suicidality subscale, which includes questions about mental imagery.17

Suicide Intent Scale. Developed by Beck et al,18 the SIS is a clinician-rated, 15-item scale assessing both circumstantial evidence and the individual’s subjective feeling of intent for a specific suicide attempt. Items are scored 0–2, with a total score range of 0–30. The SIS exhibits a high degree of interrater reliability and validity.18

Scale for Assessment of Lethality of Suicide Attempt. The SALSA comprises 2 components: 4 items indicating the gravity and anticipated consequences of the attempt and a general impression of lethality. All items are scored 1–5, with higher scores indicating increased lethality. Its validity has been established through comparisons with other scales like the Lethality of Suicide Attempt Rating Scale and the Risk Rescue Rating Scale.19

Operationalization of Suicidal Mental Imagery

Suicidal mental imagery was defined as internally generated, event-focused sensory representations related to self-harm or the suicidal act (eg, visual scenes of the attempt or its aftermath), encompassing modality, vividness, controllability/intrusiveness, frequency, timing, and associated distress. In this study, suicidal mental imagery was assessed using a pragmatic proxy derived from clinical questioning rather than a dedicated imagery instrument.

Sampling Procedure and Data Collection

Patients meeting the inclusion criteria were consecutively selected from those seeking psychiatric treatment at the hospital. Following the selection, they were assessed for suicidal thoughts, suicidal ideation, and mental imagery using the questionnaire and assessment tools. Data were collected after obtaining the necessary permissions from the research committee and the institutional ethics committee. The total duration of the study was 1 year.

Statistical Analysis

Data were analyzed in SPSS (version 20). Descriptive statistics summarized sociodemographic and clinical variables: categorical variables as counts and percentages, and continuous variables as means with SDs. Group comparisons used χ2 for categorical variables and independent-samples t-tests. Associations were further examined using multivariable logistic regression. Two-sided P < .05 was considered statistically significant.

RESULTS

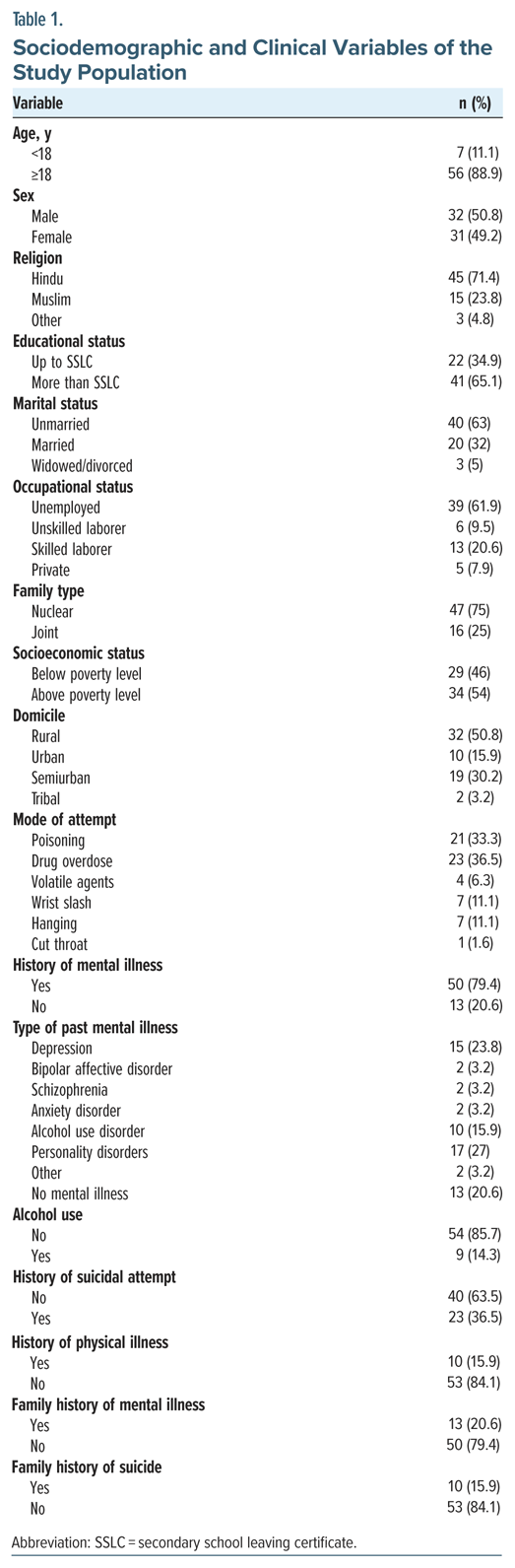

The study included 63 participants, of whom 88.9% were aged ≥18 years. The average age was calculated to be 27.3 years (SD=9.0), with a median of 26 years, and ages spanned from 15 to 54 years. The sample was nearly evenly divided by sex, with 49.2% identifying as female and 50.8% as male. A predominant majority identified as Hindu (71.4%), while 28.6% adhered to other faiths, including approximately 24% who were Muslims. In terms of educational attainment, 34.9% had completed their education up to the secondary school certificate, whereas 65.1% possessed qualifications beyond this level. A substantial proportion of participants were single (68.3%). Concerning financial status, 61.9% reported having no source of income. Most participants hailed from nuclear families (74.6%). According to socioeconomic classifications, 46.0% were categorized as below poverty line based on ration card assessments. A slightly greater number of participants resided in rural (54.0%) compared to urban settings. The methods employed for attempts included drug overdose (36.5%), poisoning (33.3%), hanging (11.1%), wrist slashing (11.1%), use of volatile agents (6.3%), and throat cutting (1.6%).

A history of mental illness was reported by 79.4%. Diagnoses among participants included depression (23.8%), bipolar affective disorder (3.2%), schizophrenia (3.2%), anxiety disorder (3.2%), alcohol use disorder (15.9%), personality disorders (27.0%), and other disorders (3.2%); 20.6% reported no mental illness. Most participants reported no alcohol use (85.7%). The number of prior suicide attempts varied: 65.1% had none, 12.7% had 1, 7.9% had 2, 7.9% had 4, 3.2% had 5, and 3.2% had 10 attempts. Among those with prior attempts, methods previously used included drug overdose (1.6%), wrist slashing (9.5%), throat cutting (1.6%), jumping into a well (1.6%), hanging (1.6%), and multiple methods (19.0%), while 65.1% had no past attempts. A history of physical illness was reported by 15.9%. Reported physical conditions included anemia (3.2%), diabetes (3.2%), thyroid disorder (3.2%), dementia (1.6%), and other illnesses (4.8%); 84.1% had no physical illness. A family history of mental illness was reported by 20.6%. A family history of suicide was present in 15.9%. The sociodemographic and clinical characteristics are summarized in Table 1.

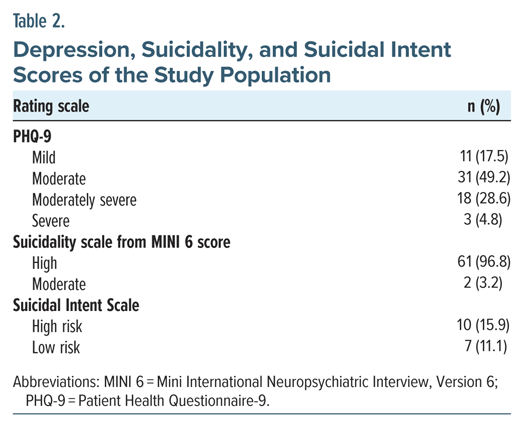

Among the participants, 15.9% were classified as high-risk, 73.0% as medium risk, and 11.1% as low risk. Depression severity was distributed as follows: 17.5% had mild depression, 49.2% moderate depression, 28.6% moderately severe depression, and 4.8% severe depression. Suicidality was predominantly high, with 96.8% showing a high suicidality score and 3.2% showing a moderate score. Scale scores were as follows: the Brief Symptom Inventory ranged from 7 to 23 (mean=15.6, SD=3.7), the SALSA ranged from 11 to 24 (mean=16.7, SD=3.1), and the PHQ-9 ranged from 5 to 20 (mean=13.2, SD=3.8). The details are summarized in Table 2.

Mental Imagery

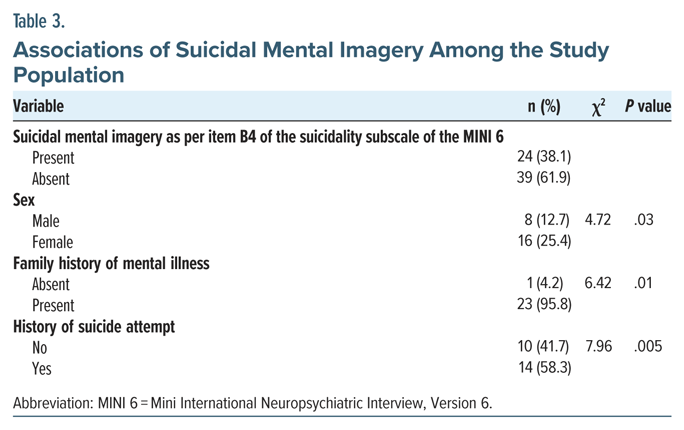

Mental imagery was present in 38.1% of participants. Among those with mental imagery, 25.4% were female and 12.7% were male, indicating a significant association between the presence of mental imagery and sex (χ2 = 4.72, P = .036). Occupational status also showed a significant association: among participants without mental imagery, 51.3% reported no income source, and 48.7% had an income source, whereas among those with mental imagery, 79.2% were without an income source, and 20.8% had an income source (χ2 = 4.89, P = .027). These results suggest that sex and occupational status are associated with the presence of mental imagery, while other demographic variables did not show significant associations in this sample. Past psychiatric history was also related to mental imagery: among participants without mental imagery, mental illness was present in 69.2% and absent in 30.8%, whereas among those with mental imagery, mental illness was present in 95.8% and absent in 4.2% (χ2 = 6.42, P = .01).

Continuous scale comparisons indicated higher symptom burden among participants with mental imagery. Mean PHQ-9 scores were 12.36 (SD=4.26) in the nonimagery group and 14.67 (SD=2.39) in the imagery group, a statistically significant difference (t = −2.426, P = .018; 95% CI of mean difference, −4.21 to −0.405). Mean suicidality MINI scores were 42.97 (SD = 13.95) without mental imagery and 50.42 (SD = 10.55) with mental imagery, also significantly higher in the imagery group (t = −2.245, P = .028; 95% CI, −14.07 to −0.814). In multivariable logistic regression including PHQ-9, suicidality, sex, and occupation, the model significantly distinguished participants with versus without mental imagery (model χ2 (4) = 14.774, P = .005) and explained approximately 20.9% to 28.4% of the variance in mental imagery. The details are summarized in Table 3.

DISCUSSION

This study examined the prevalence and correlates of mental imagery among individuals who have attempted suicide, offering insights into its role within this high-risk population. In the current study, mental imagery was reported by 38.1% of participants. This finding indicates a significant, albeit not universal, occurrence of mental imagery in individuals with a history of suicide attempts. The prevalence of suicidal mental imagery in our study is lower than in prior research. Holmes et al20 found that all 15 participants with depression and suicidal ideation experienced suicidal mental imagery. Crane et al21 reported that 78% of individuals with depression encountered suicidal imagery. Lawrence et al11 discovered that 75% of emerging adults with suicidal thoughts had suicidal mental imagery, with 56.41% expressing suicidal thoughts visually rather than verbally. The lower rate in our study may be due to differences in sample characteristics or assessment methods. Our study focused on individuals who attempted suicide, rather than those with suicidal ideation. Some suicide attempts may be impulsive or influenced by substance use, not consistently preceded by vivid mental imagery, affecting prevalence in the attempter cohort.

Despite variations in prevalence, our study found consistent associations between mental imagery and factors like depression severity and past suicide attempts, reinforcing its importance as a clinical marker of suicide risk.11,15,22 More vivid, realistic, and distressing images are linked to heightened severity of suicidal thoughts, highlighting the need to understand and assess mental imagery for risk evaluation and intervention strategies.12 Our study also identified a significant association between sex and mental imagery, with females more likely to report experiencing it than males, aligning with previous research on general gender differences in mental imagery.23 However, the specific relationship between sex and suicidal mental imagery requires further research for clarification.

The data showed no significant link between marital status and mental imagery.24 Previous studies linked marital status with suicide risk. Lee et al25 identified separation or widowhood as a risk factor for attempted suicide in older adults, and Joiner et al26 linked being unmarried with heightened suicidal ideation, but our findings suggest that marital status may not apply to mental imagery. This finding implies that different factors may influence mental imagery compared to overall suicide risk.

A significant association was observed between occupational status and mental imagery in this study. Unemployed participants reported more instances of mental imagery than their employed counterparts. This finding highlights a prevalence of mental imagery among the unemployed, an area not extensively documented in prior literature, despite the link between unemployment and increased suicide risk.27 This relationship may reflect the impacts of occupational stress, the lack of cognitive engagement, or the vulnerability of low-income groups, suggesting that socioeconomic factors may influence the frequency of suicidal mental imagery, warranting further inquiry.

This study found that individuals with a history of prior suicide attempts had a heightened propensity for mental imagery compared to those without such a history, aligning with earlier research on suicidal mental imagery. Theoretical frameworks suggest a potential role of mental imagery in perpetuating suicidal ideation and behavior.28 Individuals with a background of depression and suicidal ideation frequently reported encountering intrusive imagery pertaining to suicide.20 This study also found a correlation between a prior history of mental illness and the manifestation of mental imagery, aligning with literature associating mental health conditions with vivid and intrusive imagery. These results reinforce the understanding that mental disorders elevate the risk of suicidal ideation and behaviors, elucidating the role of mental imagery within this continuum.29

This study found a strong link between depression and mental imagery. High PHQ-9 scores were associated with increased mental imagery. Previous research shows a connection between depression severity and vivid negative imagery. Meta-analyses like that of Ribeiro et al30 also link depression to suicidal thoughts and behaviors. A study on individuals with depression and suicidal tendencies found that vivid mental imagery often accompanies their most desperate moments, including planning and attempting suicide.

This study found that high scores on the suicidality subscale were linked to increased mental imagery. This finding supports the idea that mental imagery worsens suicidal thoughts, as suggested by Holmes et al.20 It also agrees with past research showing that vivid and recurring suicidal imagery is tied to more severe suicidal thoughts.

Future Research Directions

Future studies should use longitudinal designs to clarify causality between suicidal mental imagery and outcomes and improve generalizability. Research should characterize imagery content and features with better measures and test targeted interventions in clinical trials. Neuroimaging and ecological momentary assessment can provide additional insights.

Limitations

This cross-sectional study offers a single snapshot and cannot infer causality. The small sample limits generalizability, and the absence of a nonsuicidal control group hampers conclusions about imagery specificity. Self-report measures may introduce recall bias, and unmeasured confounders could influence observed associations. We also acknowledge that the suicidal mental imagery measure is a proxy and may underestimate or misclassify imagery relative to validated instruments.

CONCLUSION

Mental imagery is common among individuals who have attempted suicide. Associations with sex, occupational status, mental illness history, and previous suicide attempts provide insights for prevention strategies. Females and those without consistent income may benefit from targeted interventions. Comprehensive mental health care and follow-up are crucial for those at elevated risk. The relationship between depression, suicidality, and mental imagery suggests that addressing imagery could be important for treatment and prevention.

Article Information

Published Online: February 12, 2026. https://doi.org/10.4088/PCC.25m04071

© 2026 Physicians Postgraduate Press, Inc.

Submitted: September 2, 2025; accepted November 11, 2025.

To Cite: Swavab P, Rahman AMAU, Uvais NA. Suicidal mental imagery in suicide attempters: a cross-sectional study. Prim Care Companion CNS Disord 2026;28(1):25m04071.

Author Affiliations: Department of Psychiatry, Government Medical College, Kozhikode, India (Swavab, Rahman); Department of Psychiatry, Iqraa International Hospital and Research Centre, Calicut, Kerala, India (Uvais).

Corresponding Author: N. A. Uvais, MBBS, DPM, Department of Psychiatry, Iqraa International Hospital and Research Centre, Calicut, Kerala, India ([email protected]).

Financial Disclosure: None.

Funding/Support: None.

Clinical Points

- Clinicians should routinely ask about suicidal mental imagery during postattempt assessments.

- A pragmatic, low-burden screening approach should be utilized, while acknowledging measurement limits.

- Imagery should be targeted directly in safety planning and early interventions.

References (30)

- Lovero KL, Dos Santos PF, Come AX, et al. Suicide in global mental health. Curr Psychiatry Rep. 2023;25(6):255–262. PubMed CrossRef

- Cerel J, Jordan JR, Duberstein PR. The impact of suicide on the family. Crisis. 2008;29(1):38–44. PubMed CrossRef

- Orsolini L, Latini R, Pompili M, et al. Understanding the complex of suicide in depression: from research to clinics. Psychiatry Investig. 2020;17(3):207–221. PubMed CrossRef

- Abhijita B, Gnanadhas J, Kar SK, et al. The NCRB suicide in India 2022 report: key time trends and implications. Indian J Psychol Med. 2024;46(6):606–607. PubMed CrossRef

- Vijayakumar L. Exam failure suicides and policy initiatives in India. Lancet Reg Health Southeast Asia. 2024;28:100443. PubMed CrossRef

- Radhakrishnan R, Andrade C. Suicide: an Indian perspective. Indian J Psychiatry. 2012;54(4):304–319. PubMed CrossRef

- Pandey GN. Biological basis of suicide and suicidal behavior. Bipolar Disord. 2013;15(5):524–541. PubMed CrossRef

- Harmer B, Lee S, Rizvi A, et al. Suicidal ideation. [Updated 2024 Apr 20]. In: StatPearls [Internet]. StatPearls Publishing; 2025. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK565877/

- Motillon-Toudic C, Walter M, Séguin M, et al. Social isolation and suicide risk: literature review and perspectives. Eur Psychiatry. 2022;65(1):e65. PubMed CrossRef

- Pearson DG, Deeprose C, Wallace-Hadrill SM, et al. Assessing mental imagery in clinical psychology: a review of imagery measures and a guiding framework. Clin Psychol Rev. 2013;33(1):1–23. PubMed CrossRef

- Lawrence HR, Nesi J, Schwartz-Mette RA. Suicidal mental imagery: investigating a novel marker of suicide risk. Emerg Adulthood. 2022;10(5):1216–1221. PubMed CrossRef

- De Rozario MR, Van Velzen LS, Davies P, et al. Mental images of suicide: theoretical framework and preliminary findings in depressed youth attending outpatient care. J Affect Disord Rep. 2021;4:100114. PubMed CrossRef

- Holman MS, Williams MN. Suicide risk and protective factors: a network approach. Arch Suicide Res. 2022;26(1):137–154. PubMed CrossRef

- De Beurs D, Fried EI, Wetherall K, et al. Exploring the psychology of suicidal ideation: a theory driven network analysis. Behav Res Ther. 2019;120:103419. PubMed CrossRef

- Lawrence HR, Balkind EG, Ji JL, et al. Mental imagery of suicide and non-suicidal self-injury: a meta-analysis and systematic review. Clin Psychol Rev. 2023;103:102302. PubMed CrossRef

- Indu PS, Anilkumar TV, Vijayakumar K, et al. Reliability and validity of PHQ-9 when administered by health workers for depression screening among women in primary care. Asian J Psychiatr. 2018;37:10–14. PubMed CrossRef

- Sheehan DV, Lecrubier Y, Sheehan KH, et al. The Mini-International Neuropsychiatric Interview (M.I.N.I.): the development and validation of a structured diagnostic psychiatric interview for DSM-IV and ICD-10. J Clin Psychiatry. 1998;59(suppl 20):22–33. quiz 34-57.

- Beck AT, Schuyler D, Herman I. Development of Suicidal Intent Scales. In: Beck AT, Resnik HLP, Lettieri DJ, eds. The Prediction of Suicide. Charles Press; 1974:45–56.

- Kar N, Arun M, Mohanty M, et al. Scale for assessment of lethality of suicide attempt. Indian J Psychiatry. 2014;56(4):337–343. PubMed CrossRef

- Holmes EA, Crane C, Fennell MJ, et al. Imagery about suicide in depression-“Flash-forwards”? J Behav Ther Exp Psychiatry. 2007;38(4):423–434. PubMed CrossRef

- Crane C, Shah D, Barnhofer T, et al. Suicidal imagery in a previously depressed community sample. Clin Psychol Psychother. 2012;19(1):57–69. PubMed CrossRef

- Lawrence HR, Nesi J, Burke TA, et al. Suicidal mental imagery in psychiatrically hospitalized adolescents. Res Child Adolesc Psychopathol. 2021;49(3):393–399. PubMed CrossRef

- Campos A, Pérez-Fabello MJ, Gómez-Juncal R. Gender and age differences in measured and self-perceived imaging capacity. Pers Individ Differ. 2004;37(7):1383–1389.

- Andrade J, May J, Deeprose C, et al. Assessing vividness of mental imagery: the plymouth sensory imagery questionnaire. Br J Psychol. 2014;105(4):547–563. PubMed CrossRef

- Lee H, Seol KH, Kim JW. Age and sex-related differences in risk factors for elderly suicide: differentiating between suicide ideation and attempts. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2018;33(2):e300–e306. PubMed CrossRef

- Joiner TE, Hom MA, Hagan CR, et al. Suicide as a derangement of the self-sacrificial aspect of eusociality. Psychol Rev. 2016;123(3):235–254. doi:10.1037/rev0000020. PubMed CrossRef

- Mathieu S, Treloar A, Hawgood J, et al. The role of unemployment, financial hardship, and economic recession on suicidal behaviors and interventions to mitigate their impact: a review. Front Public Health. 2022;10:907052. PubMed CrossRef

- O’Connor RC, Kirtley OJ. The integrated motivational-volitional model of suicidal behaviour. Philos Trans R Soc Lond B Biol Sci. 2018;373(1754):20170268. PubMed

- Hawton K, Casañas I, Comabella C, et al. Risk factors for suicide in individuals with depression: a systematic review. J Affect Disord. 2013;147(1–3):17–28. PubMed

- Ribeiro JD, Huang X, Fox KR, et al. Depression and hopelessness as risk factors for suicide ideation, attempts and death: meta-analysis of longitudinal studies. Br J Psychiatry. 2018;212(5):279–286. PubMed CrossRef

Enjoy this premium PDF as part of your membership benefits!