Unilateral abdominal or truncal seizures are uncommon and have only been documented in a handful of reports in the published literature. The previously reported patients did not exhibit clear electroencephalographic (EEG) correlations, with the exception of a few cases of epilepsia partialis continua.1

Contrary to the face, hand, and limbs, the abdominal wall and trunk have a smaller cortical representation; this was first shown in electrostimulation research by Penfield and Rasmussen.2 A new intraoperative investigation provides more evidence that the homunculus’s abdomen portion is smaller than its other sections, and the relatively small size of the homunculus’s abdominal region has been suggested as the cause of this rare kind of seizure.3

Due to the restricted cerebral representation, individuals who experience seizures characterized by unilateral abdominal clonic jerks frequently do not exhibit epileptiform abnormalities on ictal or interictal EEG, which further complicates diagnosis. We describe a case from our institution of focal aware motor seizures associated with abdominal clonic/myoclonic jerks, which was first thought to be a manifestation of underlying anxiety.

Case Report

A 14-year-old developmentally normal boy, with no significant past medical or psychiatric illness, was referred for psychiatry evaluation for chief complaints of sporadic, brief episodes of involuntary, painless abdominal movements on the left side of the abdomen for the past month. The frequency of such episodes was 1–2 per week, lasting less than 2 minutes. The patient’s awareness was intact prior to, during, and after the episodes as determined by the clinical history, and he had no visceral, autonomic, visual, or sensory symptoms. On review of the video taken by his parents, there was unilateral clonic jerking of the left side of the anterior abdominal wall seen between the left costal margin and iliac crest that did not spread to involve any other body part. He could not control these movements and could converse normally during the episode with intact awareness. There was no aura or postictal headache aphasia or drowsiness. Suggestibility could not be established. The semiology was the same in all the episodes.

Postictal anxiety and restlessness followed these episodes, which usually persisted for around an hour. These episodes were not documented during sleep and did not change in response to positional changes, tactile stimuli, speech, or distraction. There were no aggravating or relieving factors. The only notable family history was the mother’s generalized anxiety for which she was undergoing treatment. The neurological evaluation of the patient was unremarkable.

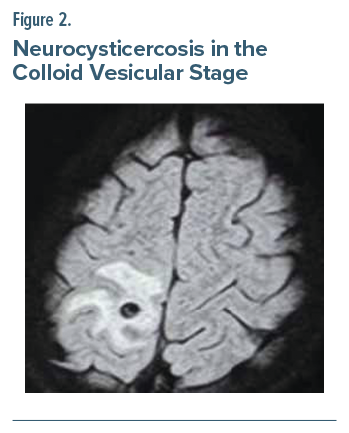

His brain magnetic resonance imaging demonstrated a well-defined cystic area, spanning around 6.5×6.4 mm, showing a T2 hypointense rim with an eccentric scolex in the right perirolandic region, along with mild perilesional edema, likely granulomatous in nature, suggesting neurocysticercosis (NCC) in the colloid vesicular stage (Figures 1 and 2). Interictal EEG was unremarkable. A video EEG (VEEG) could not be done, as the frequency of seizures was too short to be captured over a brief admission period.

The seizures responded to oxcarbazepine 300 mg twice a day and have completely ceased as reported by the patient and his guardians over regular follow-ups in the subsequent month. The patient received oral steroids for 2 weeks and antiparasitic therapy with albendazole (15 mg/kg for 2 weeks) starting 3 days after steroids after ruling out ocular NCC. Over subsequent follow-ups, the antiepileptic will be titrated to an adequate dose according to body weight. At his most recent follow-up visit at the 13th week, the patient reported occasional headaches in the right parietal region but no further seizure episodes, and oxcarbazepine was titrated to 450 mg/day. The patient is scheduled to be reimaged after 6 months of treatment.

Discussion

Focal motor seizures involving predominantly the abdominal musculature are uncommon. Unilateral abdominal clonic/ myoclonic movements as a form of epileptic event are even rarer. There have been previous reports of unilateral abdominal myoclonic jerks secondary to contralateral structural lesion,4 while 1 report was due to inflammatory granuloma secondary to NCC in the contralateral precentral gyrus.5

Due to the rather small representation of abdomen in the motor homunculus (precentral gyrus of the frontal lobe), clonic/myoclonic movements of the abdominal wall are an uncommon manifestation of epilepsy. The role of primary motor cortex in ictal transmission may be a probable explanation for this unusual presentation. In abdominal motor seizures, scalp EEG recordings are not as helpful to accurately localize the epileptogenic and symptomatic zones predominantly because of their deep foci, and VEEG could not be obtained in this patient, which we recognize as a possible limitation.

The differentials must include diaphragmatic myoclonus, truncal dyskinesia, propriospinal myoclonus, spinal segmental myoclonus, and functional or psychiatric disorders.6 Therefore, to aid medical practitioners in making an early diagnosis and providing appropriate treatment, reporting is essential. Novel electrophysiological and molecular imaging approaches along with ictal VEEG may help to elucidate the relevant epileptic circuits.7

Article Information

Published Online: August 5, 2025. https://doi.org/10.4088/PCC.25cr03926

© 2025 Physicians Postgraduate Press, Inc.

Prim Care Companion CNS Disord 2025;27(4):25cr03926

Submitted: January 27, 2025; accepted April 18, 2025.

To Cite: Chowdhry S, Pandey A, Garg S, et al. Beyond the brain: unilateral abdominal seizures as a manifestation of neurocysticercosis. Prim Care Companion CNS Disord 2025;27(4):25cr03926.

Author Affiliations: Department of Psychiatry, Shri Guru Ram Rai Institute of Medical and Health Sciences, Uttarakhand, India (Chowdhry, Garg, Bhatia); Department of Pediatric Neurology, Army Hospital, Research and Referral, New Delhi, India (Pandey).

Corresponding Author: Simran Chowdhry, MD, Department of Psychiatry, Shri Guru Ram Rai Institute of Medical and Health Sciences, Uttarakhand 248001, India ([email protected]).

Relevant Financial Relationships: None.

Funding/Support: None.

Patient Consent: Consent was obtained from the patient’s guardians to publish the case report, and information has been de-identified to protect patient anonymity.

References (7)

- Aljaafari D, Nascimento FA, Abraham A, et al. Unilateral abdominal clonic seizures of parietal lobe origin: EEG findings. Epileptic Disord. 2018;20(2):158–163.

- Penfield W, Rasmussen T. The cerebral cortex of man: a clinical study of localization of function. Macmillan. 1950.

- Patterson A, Woodroffe S, Sadler RM. Unilateral abdominal clonic jerking as an epileptic phenomenon. Epilepsy Behav Rep. 202;16:100480.

- Tatum KB, Schuele SU, Templer JW, et al. True abdominal epilepsy is clonic jerking of the abdominal musculature. Epileptic Disord. 2020;22(5):582–591.

- Asranna A, Sureshbabu S, Mittal G, et al. Abdominal epilepsia partialis continua in neurocysticercosis. Epileptic Disord Int Epilepsy J Videotape. 2019;21(3):302–306.

- Rissardo JP, Vora NM, Tariq I, et al. Unraveling belly dancer’s dyskinesia and other puzzling diagnostic contortions: a narrative literature review. Brain Circ. 2024;10(2):106–118.

- Lizarraga KJ, Serrano EA, Tornes L, et al. Isolated abdominal motor seizures of mesial parietal origin: epileptic belly dancing? Movement Disord Clin Pract. 2019;6(5):396.

Enjoy this premium PDF as part of your membership benefits!