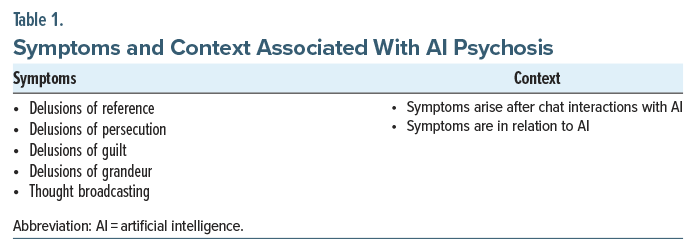

Artificial intelligence (AI) psychosis, first described in 2023, is a theoretical presentation of psychosis with potential symptoms (Table 1) that arise after interactions with, and relate significantly to, AI.1,2 While research into how AI tools may be harnessed within psychiatry has grown rapidly,3–6 literature examining how AI may exacerbate psychosis is sparse. We present the case of a patient with symptoms of psychosis related to frequent occupational use of AI.

Case Report

Mr A is a 41-year-old man with a relevant history of substance-induced psychosis (anabolic steroids, cannabis) and anxiety who presented to the emergency department (ED) after calling the police due to feeling “spooked.” On initial assessment, Mr A appeared disorganized and tangential when discussing events precipitating his presentation, reporting being at a hotel after a disagreement with his parents. His father reported that the patient was agitated, yelling about AI and his freelance work with it. He stated that the patient had been sleeping minimally due to working increasingly long hours with AI. While at the hotel, the patient felt that “unseen forces were at play,” targeting him due to his work with AI. Fearing for his safety, he contacted the police and was brought to the ED.

The patient reported writing works focused on AI “quantum research,” with topics including “ritual thermodynamics, memes being weaponized, and ransomware and symbols used in a dangerous way.” He relied on the usage of AI modalities for the purposes of asking questions, compiling data on topics of interest, and “generating symbols,” believing one such symbol to be reminiscent of a symbol from his childhood.

Mr A’s father reported that the patient utilized cannabis, as well as human growth hormone and testosterone. This was confirmed via urine drug screen and low follicle-stimulating hormone/luteinizing hormone, suggestive of anabolic steroid usage. When offered inpatient psychiatric admission for his symptoms, the patient declined. Given the significant contribution of psychoactive substances in his presentation and lack of imminent threat to self/others, he did not qualify for involuntary admission based on state statutes. The following day, the patient declined further psychiatric intervention and was discharged from the ED.

Discussion

While our patient’s presentation appeared to be related to substance use, his delusions and paranoia were focused solely on AI. Use of AI likely exacerbated his symptoms, as he felt that he needed to work increasingly long hours with AI at the cost of his sleep. This may have caused a positive feedback loop, progressively worsening his symptoms. Recent work on AI psychosis hypothesized that individuals experiencing this phenomenon could be subject to delusions of persecution, reference, grandeur, guilt, and thought broadcasting related to AI.1 Although Mr A lacked symptoms of thought broadcasting and delusions of guilt, he presented with delusions of persecution (targeted for discoveries made using AI), reference (image generated referencing a childhood symbol), and grandeur (being a pioneer in the field of quantum research). Additionally, it is unclear if he experienced frank auditory disturbances that made him fearful while alone.

With AI psychosis being a more recently described phenomenon, much of the work around AI psychosis has focused on defining it. There is neither a current standard for diagnosis or recognition of this phenomenon, nor an accepted treatment approach. Thus far, there have been no reports, to our knowledge, of AI psychosis occurring in the context of substance-induced psychosis or co-occurring with other mental health conditions. This represents a literature gap that will be critical to explore further in the future.

Conclusion

As AI tools develop further and become more commonplace,7–9 their use will likely become more widespread. As a result, more individuals suffering from psychotic or delusional disorders may adopt AI themes into paranoid and delusional schemas. Delusions are often reflective of broader societal themes; as AI continues to dominate the broader zeitgeist, further characterization is warranted of typical/atypical traits of AI psychosis, its relation to other diagnoses, and potential treatments to ameliorate symptoms.

Article Information

Published Online: December 30, 2025. https://doi.org/10.4088/PCC.25cr04059

© 2025 Physicians Postgraduate Press, Inc.

Prim Care Companion CNS Disord 2025;27(6):25cr04059

Submitted: August 15, 2025; accepted September 25, 2025.

To Cite: Caldwell MR, Ho PA. Machine madness: a case of artificial intelligence psychosis co-occurring with substance-induced psychosis. Prim Care Companion CNS Disord 2025;27(6):25cr04059.

Author Affiliations: Department of Psychiatry, Dartmouth-Hitchcock Medical Center, Lebanon, New Hampshire (Caldwell, Ho).

Corresponding Author: Patrick A. Ho, MD, MPH, Department of Psychiatry, Dartmouth Hitchcock Medical Center, One Medical Center Drive, Lebanon, NH 03756 ([email protected]).

Relevant Financial Relationships: None.

Funding/Support: None.

Additional Information: Information has been de-identified to protect patient anonymity.

References (9)

- Østergaard SD. Will generative artificial intelligence chatbots generate delusions in individuals prone to psychosis?. Schizophr Bull. 2023;49(6):1418–1419. PubMed

- Morrin H, Nicholls L, Levin M, et al. Delusions by design? How everyday AIs might be fuelling psychosis (and what can be done about it). Published online July 11, 2025. doi:10.31234/osf.io/cmy7n_v5 CrossRef

- Cao Z, Setoyama D, Natsumi Daudelin M, et al. Leveraging machine learning to uncover the hidden links between trusting behavior and biological markers. Dialogues Clin Neurosci. 2025;27(1):201–215. PubMed CrossRef

- Heinz MV, Mackin DM, Trudeau BM, et al. Randomized trial of a generative AI chatbot for mental health treatment. NEJM AI. Published online March 27, 2025. doi:10.1056/AIoa2400802 CrossRef

- van de Mortel LA, Bruin WB, Alonso P, et al. Development and validation of a machine learning model to predict cognitive behavioral therapy outcome in obsessive-compulsive disorder using clinical and neuroimaging data. J Affect Disord. 2025;389:119729. PubMed CrossRef

- Nagata Y, Satake Y, Yamazaki R, et al. A conversational robot for cognitively impaired older people who live alone: an exploratory feasibility study. Psychogeriatrics. 2025;25(5):e70076. PubMed CrossRef

- Pendell R. AI use at work has nearly doubled in two years. Gallup. 2025. Accessed August 12, 2025. https://www.gallup.com/workplace/691643/work-nearly-doubled-two-years.aspx

- McClain C, Kennedy B, Gottfried J, et al. How the U.S. Public and AI Experts View Artificial Intelligence. Pew Research Center; 2025. https://www.pewresearch.org/wp-content/uploads/sites/20/2025/04/pi_2025.04.03_us-public-and-ai-experts_report.pdf

- Singla A, Sukharevsky A, Yee L, et al. The state of AI: global survey. McKinsey. 2025. Accessed August 12, 2025. https://www.mckinsey.com/capabilities/quantumblack/our-insights/the-state-of-ai

Enjoy this premium PDF as part of your membership benefits!