Abstract

Objective: Patients with psychotic disorders have higher rates of medical comorbidities and premature mortality compared to the general population but have been shown to access primary care at low rates. Young adults are at risk of disengaging from primary care services during the transition to adulthood. This descriptive qualitative research study sought to explore barriers and facilitators to engaging with primary care among young adults with first-episode psychosis (FEP).

Methods: Ten patients aged 18–30 years receiving care in a coordinated specialty care clinic for FEP were recruited from October 2021 to December 2022. Participants were interviewed using a semistructured interview guide. Interviews were recorded and transcribed. A codebook was created inductively using data from the transcripts, and themes were generated from group consensus.

Results: Two themes relating to access to primary care were identified: (1) barriers, which included scheduling conflicts and missed appointments, active mental illness symptoms, and difficulties in rapport with the primary care physician (PCP) and (2) facilitators, which included proximity to home, absence of financial barriers, availability of urgent appointments, and caring, nonjudgmental attitudes of the PCP.

Conclusion: Improving engagement in primary care is critical for young adults with FEP to establish beneficial patterns of health care use and timely access to preventative care. This study identifies factors that may help facilitate care with PCPs, which could increase timely utilization of medical care and reduce premature mortality within this vulnerable population.

Prim Care Companion CNS Disord 2025;27(5):25m03974

Author affiliations are listed at the end of this article.

Patients with serious mental illness (SMI), including those with psychotic disorders such as schizophrenia and schizoaffective disorder, have higher rates of medical comorbidities compared to the general population.1,2 Largely due to the excess burden of cardiometabolic disease, patients with SMI die as much as 25 years earlier than those without SMI.3–5 The heightened risk of cardiometabolic disease has been linked to underlying inflammation, antipsychotic adverse effects, and lifestyle factors.6,7 Despite the higher rates of medical illness, patients with chronic psychotic illness receive fewer preventative services and less comprehensive care for chronic medical conditions.8,9 In addition, patients with SMI under-utilize primary care, while relying more heavily on emergency and inpatient services,10 and are less likely to have a primary care physician (PCP).1

The disproportionate burden of medical comorbidities starts early in the course of psychotic illness: patients with first-episode psychosis (FEP) are vulnerable to rapid weight gain and development of cardiometabolic disease, especially when initiated on antipsychotic medication.11,12 Guidelines recommend that psychiatrists monitor patients for weight gain, hypertension, glucose intolerance, and dyslipidemia,13,14 but challenges arise in getting patients to engage with primary care if abnormalities are detected. At the time of transition to adulthood, young adults are at risk of disengaging from primary care services.15 With the typical onset of psychosis in late adolescence or early adulthood, this developmental stage may represent a critical time to influence patients’ perspectives of and engagement with primary care. Establishing longitudinal medical care with a PCP is crucial to help with preventative screening for medical conditions and to initiate timely treatment for cardiometabolic diseases that are likely to occur earlier and with greater severity in this population.16,17

Previous qualitative studies on barriers to engagement with primary care for patients with SMI included patients with nonpsychotic mental illness or focused on older populations with chronic mental illness.6,18–20 Most studies were conducted in the Veterans Affairs hospital system8,18,20 or in countries with universal, government-funded health care,19,21 which may limit generalizability to community health care settings in the United States. To the authors’ knowledge, no prior studies have focused on the unique population of young adults with FEP, who are distinct in their developmental stage, phase of illness, and heightened vulnerability to rapid development of medical comorbidities. This study aimed to explore barriers to engaging with primary care among patients with FEP and to better understand patients’ preferences for accessing primary health care.

METHODS

A descriptive qualitative research method was utilized, due to the exploratory nature of the study and the ability to obtain detailed information from the perspectives of patients. The semistructured interview guide was created based on a review of available literature. The interview guide consisted of open-ended questions exploring barriers to primary care that participants experienced or perceived, as well as preferences and suggestions for making access to primary care easier (Supplementary Material). Semistructured interviews were used given the likelihood of individual differences in specific barriers and access issues, the possibility of disclosing sensitive information, and the potential for impairments in attention or memory related to psychotic illness.

Participants were recruited from the CAPSTONE FEP clinic at Pennsylvania Psychiatric Institute (PPI), a community academic outpatient psychiatric clinic in Harrisburg, Pennsylvania. The CAPSTONE clinic is a coordinated specialty care clinic for patients who have experienced new onset of psychotic illness within the previous 2 years. The clinic does not have medical or primary care services on site. Eligible participants were patients currently enrolled in the CAPSTONE FEP clinic at PPI or previously enrolled in the CAPSTONE FEP clinic since 2017, aged 18–30 years old, and able to read and write in English. Participants were recruited from October 2021 to December 2022. The CAPSTONE FEP clinic physician provided initial screening and identification of eligible patients. Potential research participants were provided information about the study and asked if they agreed to be contacted by the research coordinator. Participants were advised of the risks of participation, and they provided informed consent to participate.

One-on-one interviews were conducted by a research project coordinator (who had no clinical relationship with the patient) using the interview guide and asking follow-up questions based on individuals’ responses. The interviews were conducted using the Zoom conferencing platform and lasted approximately 30 minutes. Interviews were audio-recorded and transcribed using 3Play Media.

The research group created a codebook inductively using data from the transcripts. Two investigators independently read the interview transcripts, and a portion (20%) of the data was then coded by 2 coders (M.L. and R.D.) to reach intercoder agreement of at least 0.70. Once agreement was reached, all data were coded using MAXQDA. After the completion of coding, the research group met to discuss patterns in the data and to begin constructing themes. After reviewing the 5 preliminary themes, the team consolidated the themes to include 2 primary themes with subthemes. Themes with representative quotes are presented below. Participants who completed the semistructured interviews were provided with a $25 gift card to compensate them for their time. The study protocol was reviewed and approved by the Institutional Review Board at the Penn State College of Medicine (study ID: 17621).

RESULTS

Demographic Characteristics

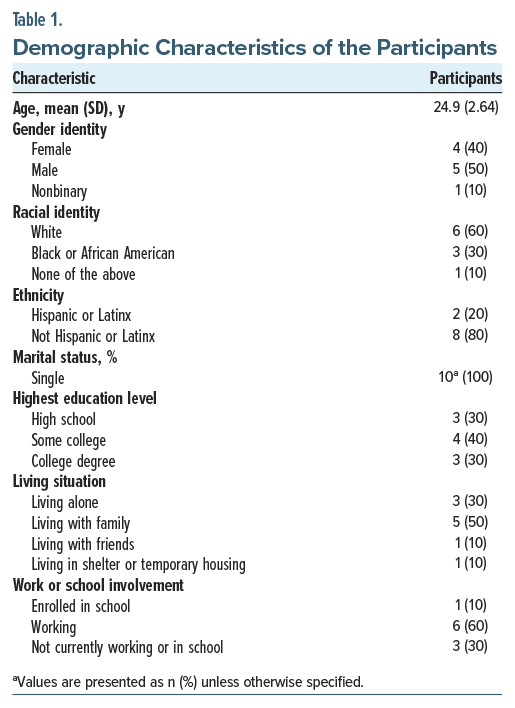

Of the 10 participants, 4 identified as female, 5 as male, and 1 as nonbinary (Table 1). The mean age was 24.9 years (SD=2.64) (range, 20–28 years). Six participants identified as white, 3 as black or African American, and 1 as none of the listed racial identities. All participants identified as single; 6 lived with family or friends, 3 lived alone, and 1 lived in temporary housing. More than half (n =6) were working, 1 was in school, and 3 were not working or in school, but none were receiving social security disability. All participants had completed high school; 4 had attended some college, and 3 had a college degree.

Thematic Analysis

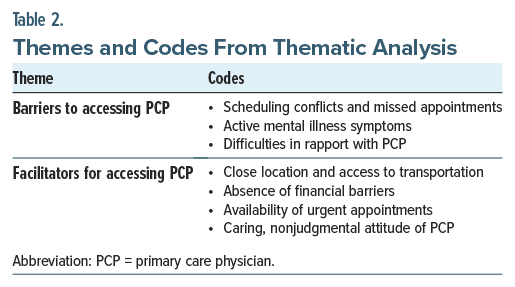

Based on the research question, “What are the barriers to access and utilization of primary care for patients with first-episode psychosis,” the research team identified 2 themes (Table 2): (1) barriers, which included scheduling conflicts and missed appointments, active mental illness symptoms, and difficulties in rapport with the PCP and (2) facilitators, which included proximity to home, absence of financial barriers, availability of urgent appointments, and caring, nonjudgmental attitudes of the PCP.

Theme 1: Barriers to Accessing PCPs. Barriers to accessing care refer to factors or obstacles that prevent individuals from entering or utilizing health care. Participants in the study expressed 3 primary barriers to accessing primary care, which are organized into the following subthemes.

Scheduling conflicts and missed appointments. Participants identified challenges fitting in appointments with their PCP’s office due to inflexible work schedules or childcare. They pointed to problems with medical appointments conflicting with work hours: “difficulty, like, fitting them into your work schedule” or “my job taking up most of the time” (that medical clinics are generally open). Participants mentioned the negative trade-off of lost wages from missing work while attending medical appointments as a deterrent to seeking care or having work that was “not really flexible” in allowing time off for appointments. Several described difficulties finding “work-life balance,” particularly trying to juggle employment, meal preparation, exercise, and childcare.

Even when primary care appointments were booked, most participants identified difficulties with forgetting and missing appointments frequently: “Something that’ll probably come in the way of me getting to my appointment would just be simple memory loss.” Others described having “a really difficult time with dates and remembering things.” They got “sidetracked” with other activities or “caught up at work” and lost track of time. Most referenced having problems with their memory for appointment dates and relying on text reminders for upcoming appointments or on loved ones to help recall appointment times.

In addition, multiple participants stated that sleeping through early morning appointments was a difficulty: “If it was during the morning, I could possibly sleep through it.” One individual explained that medication caused sedation in the mornings, and another referenced working the night shift: “A lot of the times, I just won’t wake up in time, you know, like, if it’s in the mornings or whatever and I work that night.”

Active mental illness symptoms, especially depression and anxiety. Participants in the study described how symptoms of excess anxiety could prevent them from attending medical appointments: “If I’m anxious, I might avoid going at certain times or certain dates or if I’m struggling in some way.” Others described their “mental health can be a big barrier” to taking care of their health and that feeling depressed made it “harder to get out to appointments.” They reflected that it required a “little effort” to reach out to medical professionals and that making this effort was more difficult with low motivation or low energy, resulting in missed appointments because “I just don’t feel like going.” No individuals mentioned active symptoms of psychosis as a barrier to accessing primary care.

Difficulties in rapport with PCPs. Participants described problems interacting with PCPs, feeling that their provider did not listen to them or made negative assumptions due to the diagnosis of mental illness. One participant provided an example of feeling that their PCP was “not listening to me as much as just making their own assumptions” and suggested the need for medical doctors to “change their attitudes towards people who have mental health issues . . . cause I really felt like he (my PCP) judged me.” A sense of “shame for my mental health things” was identified as an obstacle to seeking medical care. One woman identified racial discrimination as a deterrent to accessing care for physical health problems: “I would probably take into consideration, um, racial discrimination just because of my background—me being an African American woman.”

Theme 2: Facilitators to or Preferences for Accessing PCPs. Facilitators to accessing care are factors that assist people in receiving the appropriate amount or quality of care. Participants identified the following 4 subthemes as facilitators to accessing primary care or preferences for how participants would like to access primary care.

Close location to home and access to transportation. Participants wanted to have a primary care office that was conveniently close in proximity to their home (within 5–15 minutes travel time) to allow them quick access: “It’s not that far. It’s just, like, about 15 minutes away from me.” In general, they valued having a PCP that is “very close . . . right down the street from me.” Several individuals stated that personal access to a car (“the freedom of having a car”) or having family members (“I always have people that are available to me”) who could provide rides were facilitators to making it to appointments with PCPs: “My mother is my caregiver, so she takes me. We set appointments . . . when she’s off [work].”

Absence of financial barriers. Participants expressed the importance of not having financial barriers to primary care because they had adequate insurance coverage and no out-of-pocket costs for medical care. They did not have to worry about whether they could afford care “because my insurance takes care of that; I never really think about it.” With active insurance, there were no copays: “I don’t really pay for anything.” Another participant referenced having consistent access to health care because their parent provided health insurance as well as logistical and financial support.

Availability of urgent appointments. Many participants expressed the importance of being able to get an appointment for a new or urgent problem quickly at their primary care offices, preferably within 1–2 days. They appreciated that their PCP “prioritizes availability” for them and that office staff will facilitate their being seen “sooner rather than later” when there is a “more concerning issue at hand.” Conversely, for those participants whose primary care offices could not accommodate them for an urgent appointment, they would seek care at urgent care or the emergency department.

Caring, nonjudgmental attitude of provider. Participants highlighted the importance of their PCP treating them with kindness and consideration: “He’s very understanding and caring for all my problems.” Especially considering their diagnosis of mental illness, they highlighted their desire to have a provider that “wasn’t judgmental about anything” and who could “understand where you’re coming from.” They valued a provider with a positive, friendly attitude who was “easy to talk to,” made them feel “comfortable,” and “helps me feel hopeful about my future.” Participants stressed the importance of providers taking “time to talk to me” and listening intently: “I feel like they are actually wanting to listen to me and hear my voice.” They appreciated when their PCP was “straightforward” and willing to acknowledge when they did not have the answer.

DISCUSSION

This is the first study, to the authors’ knowledge, to report on barriers and facilitators to accessing primary care services for young adults with FEP. Barriers included scheduling conflicts with work or other obligations, forgetting appointments, difficulty awakening for morning appointments, and active symptoms of mental illness, particularly depression or anxiety. The identified themes for facilitators were convenient location to home, adequate insurance coverage, availability of urgent appointments, and caring, nonjudgmental attitude of the provider.

Previous publications on barriers to accessing care in patients with SMI organized them into 3 categories: (1) patient-related, (2) interpersonal, and (3) systems-related.2,3 Among the identified barriers in this study, most were patient-related (missing appointments, difficulty waking early, and active symptoms). Forgetting appointments may be attributable to significant but often under-recognized cognitive impairments in memory, attention, and executive functioning in patients with FEP.22 These deficits could interfere with recalling appointments, organizing the steps required to schedule and attend an appointment, and navigating the health care system.1 Disruptions in sleep cycle or excessive sedation from medications could make waking for appointments difficult.23 Depressive symptoms, which are frequently present in FEP,24 and negative symptoms of psychosis, including avolition and apathy, may interfere with appointment attendance. In a study of veterans with SMI, more severe psychiatric symptoms were associated with more perceived barriers to care, suggesting that psychiatric illness itself may be one of the most significant barriers to care.20

In terms of interpersonal barriers, participants in this study identified the attitude of their PCP and the provider-patient relationship as important determinants of (dis)engaging in primary care services, especially if they felt judged because of mental illness. Problems in alliance and therapeutic rapport with PCPs have been recognized as barriers to medical care for those with SMI.6,20 Patients with psychotic disorders may encounter stigma or judgment from health professionals in nonpsychiatric care settings who have less specialized training and less comfort in communicating with individuals with SMI.2,3 PCPs and their office staff may also have limited awareness of cognitive and negative symptoms of psychotic disorders that impede follow through with appointments and recommendations. Our study did not differentiate between types of PCPs; the continuity of seeing an established and trusted pediatrician or family physician into early adulthood (in contrast to switching to an adult internist) could impact engagement in primary care. The absence of family support or involvement has been identified as a predictor of disengagement from FEP services.25 In this sample, many participants referenced financial, logistical, and emotional support from parents or family to help them access primary care, highlighting the critical role of family involvement.

This sample of young adults with FEP identified systems-related facilitators including minimal cost, ease of transportation to or proximity of the PCP’s clinic, and flexibility in urgent appointments as facilitators for engaging in primary care, which is consistent with existing literature about accessing medical care in patients with chronic SMI.19,26 Fragmentation and lack of integration between behavioral health care and primary care services are reported barriers to medical care in other studies, but our participants did not perceive this as problematic.6,9,19 Those studies had older patient populations (mean ages: 43–54 years); by contrast, younger adults in the FEP population may have fewer diagnosed medical conditions and may not yet have encountered with fragmented care systems. Models that integrate medical and behavioral health care, such as reverse integration of primary care into a mental health clinic, may facilitate coordinated medical care of individuals with SMI.27

Strengths of this study include the use of a qualitative approach in understanding barriers and facilitators to accessing primary care in young adults receiving treatment for FEP. To the authors’ knowledge, this is the first study examining this unique population, which is at heightened risk for premature mortality. Although the sample size was small, data saturation was attained. Individuals with FEP who had more severe psychotic symptoms, negative symptoms, or cognitive impairments or who faced greater challenges in accessing health care may have been less likely to participate. Because these individuals are more likely to face greater obstacles to accessing medical care, the results may underestimate challenges faced by young adults with FEP in engaging with primary care. Our sample was drawn from patients actively engaged in care in an FEP clinic, so results may not be representative of the broader population of individuals with early psychosis. Those who disengage from FEP services are likely to have risk factors (such as substance use, lack of family support) that also increase the likelihood of facing barriers to accessing primary care.25 The study was conducted in Harrisburg, Pennsylvania, which may limit generalizability to other geographic areas, as many systems-level factors specific to a region impact availability of primary care.

CONCLUSION

Cardiometabolic diseases are significant but treatable contributors to early mortality in individuals with chronic psychotic illness, and PCPs have a crucial role to play in the longitudinal care of such patients.17,28 Young adulthood is a critical time for the establishment of health risk behaviors and patterns of health care use,15 and early engagement in primary care could allow timely identification of preventable diseases. This exploratory study identifies barriers and facilitators to accessing primary care in young adults with FEP, which could inform strategies for prompt treatment of emerging medical conditions in a vulnerable population.

Article Information

Published Online: October 2, 2025. https://doi.org/10.4088/PCC.25m03974

© 2025 Physicians Postgraduate Press, Inc.

Submitted: March 27, 2025; accepted June 24, 2025.

To Cite: Swigart AR, Van Scoy LJ, Dhingra R, et al. Barriers and facilitators to accessing primary care in patients with first-episode psychosis. Prim Care Companion CNS Disord 2025;27(5):25m03974.

Author Affiliations: Department of Psychiatry and Behavioral Health, The Penn State College of Medicine, Hershey, Pennsylvania (Swigart); Departments of Medicine, Humanities, and Public Health Sciences, The Penn State College of Medicine, Hershey, Pennsylvania (Van Scoy, Stuckey-Peyrot); Department of Population Health Sciences, Duke University School of Medicine, Durham, North Carolina (Dhingra); Department of Medicine, The Penn State College of Medicine, Hershey, Pennsylvania (Bordner, Costigan).

Corresponding Author: Alison Swigart, MD, Pennsylvania Psychiatric Institute, 401 Division St, Harrisburg, PA 17110 ([email protected]).

Relevant Financial Relationships: None.

Funding/Support: The research was funded by grants received from the Junior Faculty Development Program at The Penn State College of Medicine, the Department of Psychiatry and Behavioral Health at The Penn State College of Medicine, and the Joyce D. Kales, M.D. Community Psychiatry Endowment Award at The Penn State College of Medicine, Hershey, Pennsylvania.

Role of the Sponsors: The sponsors had no role in the design, analysis, interpretation, or publication of this study.

Previous Presentation: Poster presented at the American Psychiatric Association Annual Meeting; May 6, 2024; New York, New York.

Acknowledgments: The authors thank Morgan Loeffler, MA (The Penn State College of Medicine, Hershey, Pennsylvania) for assistance with data coding. Ms Loeffler has no relevant financial relationships to declare.

ORCID: Alison R. Swigart: https://orcid.org/0000-0003-0127-396X; Lauren J. Van Scoy: https://orcid.org/0000-0003-0984-1474; Radha Dhingra: https://orcid.org/0000-0003-1921-9136; Heather J. Costigan: https://orcid.org/0000-0002-2009-277X; Heather Stuckey-Peyrot: https://orcid.org/0000-0002-3200-3543

Supplementary Material: Available at Psychiatrist.com.

Clinical Points

- Young adults with first-episode psychosis (FEP) are at heightened risk for the development of cardiometabolic disease and for not engaging with primary care.

- Active symptoms of mental illness, difficulty keeping appointments, and problems in patient-provider rapport can interfere with accessing primary care in patients with FEP.

- Factors that facilitate engagement with primary care in this group are proximity to site of care, absence of financial obstacles, flexibility of appointments, and nonjudgmental attitude of the primary care provider.

References (28)

- Bradford DW, Kim MM, Braxton LE, et al. Access to medical care among persons with psychotic and major affective disorders. Psychiatr Serv. 2008;59(8):847–852. PubMed CrossRef

- Lawrence D, Kisely S. Inequalities in healthcare provision for people with severe mental illness. J Psychopharmacol. 2010;24(4 suppl):61–68. PubMed CrossRef

- Druss BG. Improving medical care for persons with serious mental illness: challenges and solutions. J Clin Psychiatry. 2007;68(suppl 4):40–44. PubMed

- McDonell MG, Kaufman EA, Srebnik DS, et al. Barriers to metabolic care for adults with serious mental illness: provider perspectives. Int J Psychiatry Med. 2011;41(4):379–387. PubMed CrossRef

- Druss BG, von Esenwein SA, Compton MT, et al. A randomized trial of medical care management for community mental health settings: the Primary Care Access, Referral, and Evaluation (PCARE) study. Am J Psychiatry. 2010;167(2):151–159. PubMed CrossRef

- Blixen CE, Kanuch S, Perzynski AT, et al. Barriers to self-management of serious mental illness and diabetes. Am J Health Behav. 2016;40(2):194–204. PubMed CrossRef

- Muir-Cochrane E. Medical co-morbidity risk factors and barriers to care for people with schizophrenia. J Psychiatr Ment Health Nurs. 2006;13(4):447–452. PubMed CrossRef

- Kilbourne AM, McCarthy JF, Post EP, et al. Access to and satisfaction with care comparing patients with and without serious mental illness. Int J Psychiatry Med. 2006;36(4):383–399. PubMed CrossRef

- Levinson Miller C, Druss BG, Dombrowski EA, et al. Barriers to primary medical care among patients at a community mental health center. Psychiatr Serv. 2003;54(8):1158–1160. PubMed CrossRef

- Hensel JM, Flint AJ. Addressing the access problem for patients with serious mental illness who require tertiary medical care. J Health Care Poor Underserved. 2015;26(1):35–48. PubMed CrossRef

- Correll CU, Robinson DG, Schooler NR, et al. Cardiometabolic risk in patients with first-episode schizophrenia spectrum disorders: baseline results from the RAISE-ETP study. JAMA Psychiatry. 2014;71(12):1350–1363. PubMed CrossRef

- Jensen KG, Correll CU, Rudå D, et al. Pretreatment cardiometabolic status in youth with early-onset psychosis: baseline results from the TEA trial. J Clin Psychiatry. 2017;78(8):e1035–e1046. PubMed CrossRef

- American Diabetes Association; American Psychiatric Association; American Association of Clinical Endocrinologists; et al. Consensus development conference on antipsychotic drugs and obesity and diabetes. J Clin Psychiatry. 2004;65(2):267–272. PubMed CrossRef

- De Hert M, Detraux J, van Winkel R, et al. Metabolic and cardiovascular adverse effects associated with antipsychotic drugs. Nat Rev Endocrinol. 2011;8(2):114–126. PubMed CrossRef

- Marshall EG. Do young adults have unmet healthcare needs?. J Adolesc Health. 2011;49(5):490–497. PubMed CrossRef

- Nielsen RE, Banner J, Jensen SE. Cardiovascular disease in patients with severe mental illness. Nat Rev Cardiol. 2021;18(2):136–145. PubMed CrossRef

- Viron M, Baggett T, Hill M, et al. Schizophrenia for primary care providers: how to contribute to the care of a vulnerable patient population. Am J Med. 2012;125(3):223–230. PubMed CrossRef

- Bauer MS, Williford WO, McBride L, et al. Perceived barriers to health care access in a treated population. Int J Psychiatry Med. 2005;35(1):13–26. PubMed CrossRef

- Björk Brämberg E, Torgerson J, Norman Kjellström A, et al. Access to primary and specialized somatic health care for persons with severe mental illness: a qualitative study of perceived barriers and facilitators in Swedish health care. BMC Fam Pract. 2018;19(1):12. PubMed CrossRef

- Drapalski AL, Milford J, Goldberg RW, et al. Perceived barriers to medical care and mental health care among veterans with serious mental illness. Psychiatr Serv. 2008;59(8):921–924.PubMed CrossRef

- McCabe MP, Leas L. A qualitative study of primary health care access, barriers and satisfaction among people with mental illness. Psychol Health Med. 2008;13(3):303–312. PubMed CrossRef

- Sheffield JM, Karcher NR, Barch DM. Cognitive deficits in psychotic disorders: a lifespan perspective. Neuropsychol Rev. 2018;28(4):509–533. PubMed CrossRef

- Davies G, Haddock G, Yung AR, et al. A systematic review of the nature and correlates of sleep disturbance in early psychosis. Sleep Med Rev. 2017;31:25–38. PubMed CrossRef

- Coentre R, Talina MC, Góis C, et al. Depressive symptoms and suicidal behavior after first-episode psychosis: a comprehensive systematic review. Psychiatry Res. 2017;253:240–248. PubMed CrossRef

- Doyle R, Turner N, Fanning F, et al. First-episode psychosis and disengagement from treatment: a systematic review. Psychiatr Serv. 2014;65(5):603–611. PubMed CrossRef

- Chadwick A, Street C, McAndrew S, et al. Minding our own bodies: reviewing the literature regarding the perceptions of service users diagnosed with serious mental illness on barriers to accessing physical health care. Int J Ment Health Nurs. 2012;21(3):211–219. PubMed CrossRef

- Ward MC, Druss BG. Reverse integration initiatives for individuals with serious mental illness. Focus (Am Psychiatr Publ). 2017;15(3):271–278. PubMed CrossRef

- Šimunović Filipčić I, Filipčić I. Schizophrenia and physical comorbidity. Psychiatr Danub. 2018;30(suppl 4):152–157. PubMed

Enjoy this premium PDF as part of your membership benefits!