Lessons Learned at the Interface of Medicine and Psychiatry

The Psychiatric Consultation Service at Massachusetts General Hospital sees medical and surgical inpatients with comorbid psychiatric symptoms and conditions. During their twice-weekly rounds, Dr Stern and other members of the Consultation Service discuss diagnosis and management of hospitalized patients with complex medical or surgical problems who also demonstrate psychiatric symptoms or conditions. These discussions have given rise to rounds reports that will prove useful for clinicians practicing at the interface of medicine and psychiatry.

Prim Care Companion CNS Disord 2025;27(5):25f03983

Author affiliations are listed at the end of this article.

Have you ever wondered which antipsychotic agent you should prescribe to your patient with psychosis? Have you struggled to balance the concepts of efficacy, tolerability, and cost? Have you been uncertain about how to switch from one agent to another without provoking a relapse or triggering intolerable side effects? If you have, the following case vignette and discussion should prove useful.

CASE VIGNETTE

Mr A, a 22-year-old man, developed his first psychotic episode (with auditory hallucinations, paranoia, thought broadcasting, and disorganized thinking), which interfered with his sophomore year of college and interpersonal relationships. He was diagnosed with schizophrenia and started on risperidone, which was gradually titrated to 3 mg twice daily. Over the next 6 months, his symptoms improved dramatically, which enabled him to resume regular activities and fulfill his academic responsibilities.

To improve his medication adherence and outcome, Mr A transitioned from oral risperidone to long-acting injectable (LAI) paliperidone palmitate (Invega Sustenna), starting with a loading dose of 234 mg on day 1 and then adding 156 mg on day 8, with subsequent by-monthly injections. After being stable for more than 4 months on Invega Sustenna, he was transitioned to Invega Trinza (546 mg every 3 months). Although his psychotic symptoms remained under control, he developed significant metabolic side effects, including a 50-lb weight gain (from 130 lb to 180 lb), with his body mass index (BMI) increasing from 18 to 25 kg/m2. Due to these metabolic changes, Mr A was prescribed metformin, which was gradually titrated to 1,000 mg twice daily. In addition, he complained of cognitive dulling as well as having difficulty initiating and following through with his activities. Mr A also developed elevated prolactin levels (95 ng/mL), which led to erectile dysfunction and gynecomastia that caused him significant distress. To address his hyperprolactinemia, aripiprazole (5 mg daily) was added, which initially reduced his prolactin level to 40 ng/mL and improved his sexual side effects slightly. After 1 month, the aripiprazole dose was increased to 10 mg daily, but at this increased dose, Mr A became anxious, restless, and started to pace (each suggesting akathisia). Due to his frustration and discomfort, Mr A abruptly discontinued his aripiprazole and declined to receive the next scheduled dose of Invega Trinza, which resulted in his relapsing and requiring hospitalization for acute stabilization.

DISCUSSION

Does Everyone With Psychotic Symptoms Have a Psychotic Illness?

Psychosis is an aberration in perceived experiences—at times involving visual and auditory hallucinations, impaired thought processes, delusions, and an inability to discern reality. Psychosis is not a diagnosis per se; instead, it is a descriptor. First-episode psychosis (due to any cause) occurs in approximately 50 of every 100,000 people annually. Its pathophysiology is variable and primarily determined by its etiology, with the common thread being an alteration in the blood-brain barrier that leads to an imbalance of neurotransmitter excitation (via glutamate and dopamine) and inhibition (via γ-aminobutyric acid) with resultant dopamine dysregulation. Only a minority of those who have experienced a first episode of psychosis develop a full-blown psychotic disorder.

When distinguishing between primary and secondary psychoses, the age of the patient, their medical history, as well as the timing of the onset and characteristics of the psychosis are crucial. Typically, primary psychoses (ie, due to psychiatric disorders) begin between the ages of 18 and 35 years and are accompanied by a subtle escalation of symptoms. Moreover, they are more likely to present with auditory hallucinations and to be seen in psychiatric settings.1

However, secondary psychoses (ie, due to medical or neurological causes) occur in 11% of individuals with psychosis. The most common causes of secondary psychosis are substance-induced psychoses and psychoses caused by infections or autoimmune conditions. Those with secondary psychoses tend to have symptoms arise acutely after the age of 40 years and develop noticeable changes in their level of functioning. Such conditions are likely to be evaluated in general hospital settings.1

When evaluating a patient with psychotic symptoms, their behavior should be observed before beginning the interview or entering the room (if feasible). The clinician should take note of self-dialoging, changes in affect, changes in stance when approached, intensity of eye contact, suspiciousness, psychomotor movements, vital sign abnormalities, and level of alertness when not being stimulated.

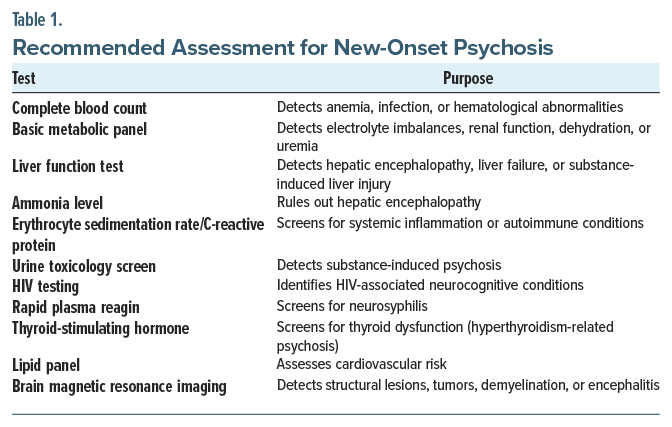

A comprehensive evaluation is crucial to reduce the chance that a secondary psychosis will be missed. Recommended assessments include laboratory and imaging tests aimed at detecting metabolic, infectious, inflammatory, endocrine, and toxic etiologies. Table 1 outlines each test and its clinical purpose.

What Types of Medical and Psychiatric Conditions Are Manifest by Psychosis?

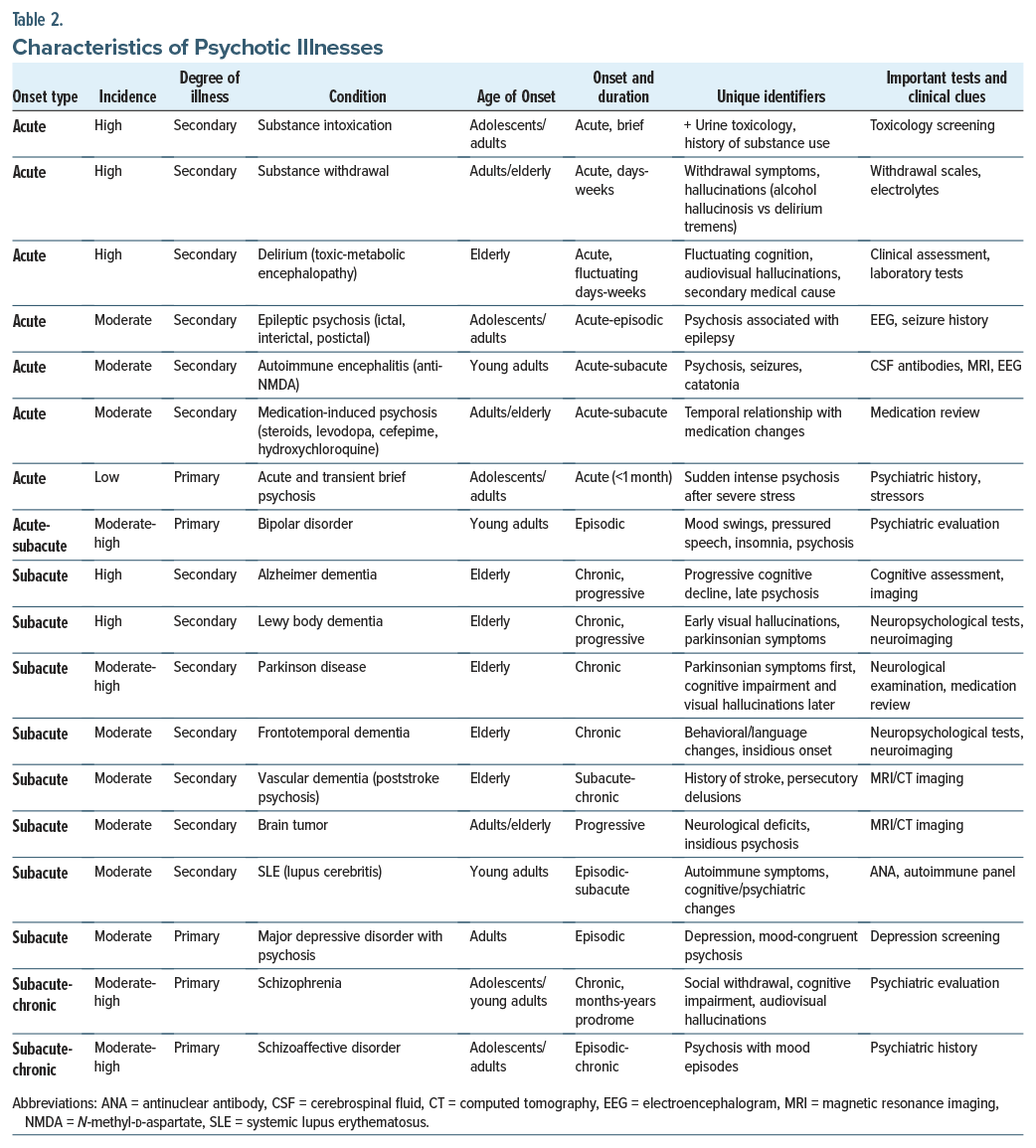

Acute onset. The most common cause of psychosis is substance-related psychosis (eg, with intoxication of amphetamine, cannabis, cocaine, phencyclidine, psychedelics, or opiates). Psychosis associated with alcohol withdrawal can lead to alcoholic hallucinosis (with auditory hallucinations, a clear sensorium, and intact cognition) or delirium tremens, which is much more severe and is accompanied by hypertension, tachycardia, diaphoresis, tremors, an altered sensorium, impaired cognition, and auditory and visual hallucinations.2

Delirium (toxic-metabolic encephalopathy) also presents with an acute-onset psychosis marked by inattention, impaired arousal, and auditory and visual hallucinations (typically of small animals and bugs), delusions, and significant fluctuations (ie, a waxing and waning course). Delirium is typically secondary to infections, metabolic derangements, or medication effects, and it is best managed by treating the specific etiology.

Epileptic seizures can also lead to an ictal, interictal, or postictal psychosis. Psychotic disorders are 8 times more common in those who carry a diagnosis of epilepsy than in those in the general population.3 Many cases require use of an antiepileptic drug for seizure control, as well as an antipsychotic to manage psychotic symptoms. Other abrupt-onset psychoses associated with seizures include autoimmune encephalitis, specifically, anti-N-methyl-D-aspartate (NMDA) encephalitis, which is manifest as psychosis followed by escalating neurological abnormalities, including seizures and catatonia.4

Medication-induced psychoses appear abruptly and are temporally associated with medication changes (eg, of steroids, antiparkinsonian agents, and antibiotics). On occasion, hallucinations arise in the context of severe psychosocial stressors and traumatic experiences (eg, acute and transient psychotic disorders) (Table 2).

Subacute onset. Dementing illnesses (eg, frontotemporal dementia, Lewy body dementia, Alzheimer disease, and vascular dementia) can be manifest by psychosis even years after the onset of insidious symptoms that involve executive dysfunction, memory impairment, and visuospatial impairment. Autoimmune disorders often present weeks to months after joint pain, pleurisy, nephropathy, or skin involvement, as well as elevated levels of biomarkers. Systemic lupus erythematosus can cause psychosis when the brain is involved (eg, lupus cerebritis).

Primary psychiatric conditions with psychosis include affective disorders (unipolar or bipolar). In unipolar depression (major depressive disorder [MDD]), low mood, neurovegetative symptoms, and mood congruent delusions and hallucinations may appear. Approximately 15% of people with MDD experience psychosis,5 typically at higher symptom severities (eg, Patient Health Questionnaire-9 score of 20). Bipolar disorder with mania or depression and psychosis may be acute or subacute and have notable mood swings. Schizophrenia typically has an extended prodrome (lasting several months), with significant social withdrawal, cognitive impairment, and auditory and visual hallucinations.

How Has the Care of Psychotic Illnesses Evolved Over the Past Century?

In the first half of the 20th century, state psychiatric hospitals grew significantly due to societal changes (eg, industrialization and urbanization altered household structure, which left the elderly in need of state care). As psychiatric hospitals became overcrowded, care was no longer aligned with moral treatment (that had been pioneered by the asylum reform efforts of Dorothea Dix in the mid-19th century); they had become warehouses characterized by inhumane treatment. The quality of care declined further when trained staff left their hospital positions to serve on the battlefields in World War II.6

Subsequently, federal policies and scientific discoveries between 1945 and 1970 changed psychiatric care forever. In 1948, the federal government established the National Institute of Mental Health; in 1954, chlorpromazine became the first antipsychotic medication to be used in the United States,7 and in 1963, President John F. Kennedy signed the Community Mental Health Centers Act, which was amended (expanded) in 1968 and again in 1970.8

In the years since deinstitutionalization, with the movement of individuals having a serious mental illness (SMI) from psychiatric facilities to the communities, the number of state psychiatric hospital beds decreased from 558,000 in 1955 to 35,000 in 2017. This translated to a loss of beds from 340 per 100,000 people to 11 per 100,000.9 Transinstitutionalization also explains the movement of people with SMI from state hospital beds to prisons, nursing homes, the streets, and homeless shelters. Although advances in psychopharmacology have ameliorated symptoms for many of those with psychotic disorders, drug treatment has not been a panacea. Moreover, a lack of adequate resources has impeded the provision of comprehensive care (eg, supported housing, transitional employment) that is needed by many of those with SMI.

After the approval of chlorpromazine, several antipsychotics were created and became available; as a class, first-generation antipsychotics (FGAs) block dopamine D2 receptors and reduce the positive symptoms of psychosis but caused movement side effects. In 1972, clozapine came to the market; however, it was removed in 1975 in many countries due to an alarming rise in the number of cases of neutropenia. However, in 1988, a pivotal study by Kane et al10 in the United States demonstrated that clozapine manifests superior efficacy in a narrowly defined cohort of those with treatment-resistant schizophrenia; response rates for clozapine in the double-blind, randomized trial were 30% for those in the clozapine arm compared to 4% in the chlorpromazine group.11 After clozapine, 13 other second-generation antipsychotics (SGAs) received US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) approval. All share 5-hydroxytryptamine (5-HT2A) and D2 antagonism, leading to metabolic side effects.12 LAI antipsychotics (eg, depot formulations for haloperidol and fluphenazine decanoates, and later other SGA options) expanded treatment flexibility. In September 2024, a novel treatment for schizophrenia was approved by the FDA, xanomeline-trospium, a muscarinic agonist, which avoids the blockade of postsynaptic D2 receptors and thus prevents the associated movement and metabolic side effects.13,14 This medication will be discussed further in a subsequent section.

How Do Antipsychotic Agents Work, and What Symptoms Do They Mitigate Most?

Schizophrenia has a complex neurobiology, for which our collective understanding remains limited.15 While monoamines (eg, dopamine, serotonin, norepinephrine) are highly implicated in the disorder, other neurotransmitters (eg, glutamate, acetylcholine) are also involved. Further, each symptom cluster (eg, positive, negative, cognitive) has a unique neurobiology, and there is heterogeneity within each symptom cluster among individuals with schizophrenia. For instance, many patients who meet criteria for treatment-resistant schizophrenia are thought to have aberrancies that are unrelated to dopamine signaling, hence their poor response to conventional treatments.16 Given these complexities, antipsychotics remain relatively blunt tools that often modulate biology downstream of a poorly understood underlying pathophysiology. Nonetheless, they offer substantial benefits for many individuals with psychotic disorders, and their use remains the standard of care in psychiatry.

Broadly speaking, the unifying mechanism of action among antipsychotics in schizophrenia has been based on dopamine D2 receptor blockade.17 Specifically, reduction of dopaminergic activity along the mesolimbic circuit at the striatum is thought to be the mechanism by which antipsychotics treat positive symptoms (ie, delusions, hallucinations, disorganization).17 However, dopamine dysregulation does not occur in isolation; rather, multiple other neurotransmitter systems, including serotonin, glutamate, and acetylcholine, also modulate dopamine signaling. Serotonin receptor overactivity, particularly at 5-HT2A receptors, and glutamatergic NMDA receptor hypofunction can both increase mesolimbic dopamine firing and suppress mesocortical dopamine activity, contributing to positive and negative symptoms, respectively. Similarly, cholinergic pathways influence dopaminergic tone; for example, muscarinic receptor agonists can decrease mesolimbic dopamine activity, thereby reducing positive symptoms. Off-target dopamine blockade, however, is also responsible for side effects (eg, extrapyramidal symptoms [EPS]) and worsening negative symptoms. Antipsychotic activity at other neurotransmitter receptors (such as those for serotonin, histamine, and acetylcholine) is often responsible for side effects.

Currently, there are 3 antipsychotics (aripiprazole, brexpiprazole, and cariprazine) that act as partial agonists of the D2 receptor; each contains the letters “pipra” or “ripra,” and they are sometimes referred to as “third-generation” antipsychotics.17 Two antipsychotics have little to no activity at the D2 receptor: clozapine and xanomeline-trospium.17 Interestingly, clozapine is the only antipsychotic medication currently approved by the FDA for treatment-resistant schizophrenia despite causing minimal D2 blockade. The mechanism of clozapine’s unique benefits remains somewhat unclear, although imaging studies have demonstrated a decreased glutamate signal in the caudate in response to clozapine administration.18 Xanomeline-trospium works as a muscarinic agonist at M1 and M4 receptors, and it lacks direct dopamine activity. This muscarinic agonism is thought to decrease acetylcholine in the midbrain where dopamine release is facilitated18; therefore, in the presence of xanomeline-trospium, dopamine release is reduced, but through a more selective, upstream fashion that spares motor areas, thereby avoiding EPS.

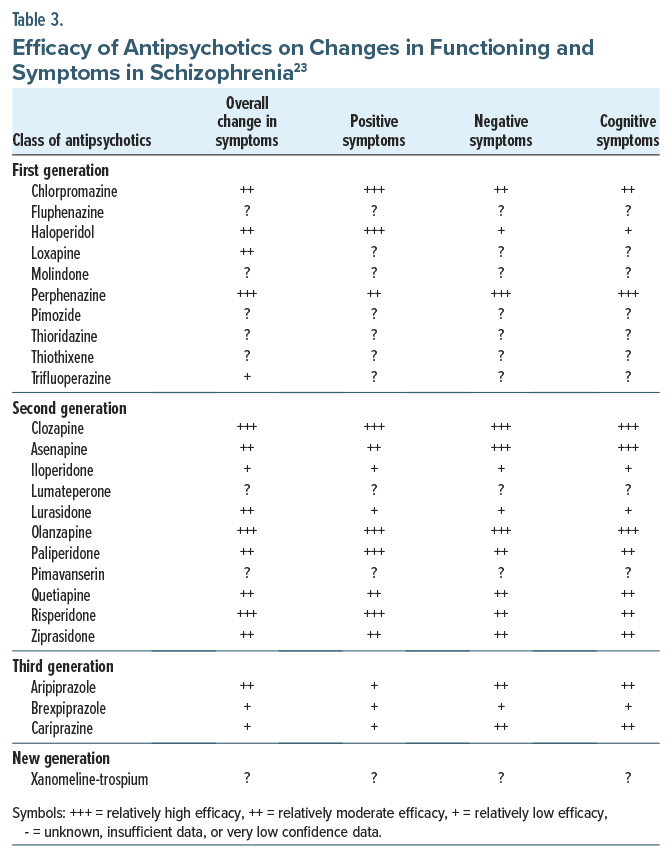

Regarding negative and cognitive symptoms, despite their consequences on real-life functioning,19 no antipsychotics have consistently been shown to be beneficial (Table 3). Moreover, antipsychotics can worsen negative and cognitive symptoms if there is an excess of off-target dopamine blockade (ie, secondary negative symptoms).17 Beyond antipsychotic medications, there are no FDA-approved treatments for negative or cognitive symptoms of schizophrenia. Often, the benefits of antipsychotics or other psychotropics on negative or cognitive symptoms are related to other factors (eg, treatment of the positive symptoms or comorbid depression). Nonetheless, pharmacologic treatment and incorporation of psychosocial treatments have been beneficial.19 Cariprazine may be a preferred antipsychotic for those with prominent negative symptoms, as it has compared favorably with risperidone20 in a manufacturer-sponsored trial, although it is unclear whether this was an epiphenomenon of cariprazine’s therapeutic benefits for depression21 or a lower risk of inducing secondary negative symptoms.22

Are Antipsychotic Agents Equally Efficacious for the Treatment of Psychotic Illnesses?

Assessment of efficacy is important when selecting an antipsychotic medication. Compared to all other antipsychotics, clozapine has superior efficacy. Clozapine is the only antipsychotic that is FDA approved for treatment-resistant schizophrenia. However, a recent meta-analysis revealed that amisulpride, olanzapine, zotepine, and risperidone also had increased efficacy for overall symptom improvement, while the oral formulations of all other FGAs and SGAs have similar efficacy. LAIs have improved efficacy compared to oral formulations, an observation that is likely related to their enhanced treatment adherence.24 LAIs are also correlated with significant improvements in morbidity and mortality rates.25 The newest antipsychotic agent, xanomeline-trospium (Cobenfy, Kar-XT), acts upstream from the dopamine receptor targeted by the FGAs and SGAs. Its efficacy compared to placebo has been demonstrated in several time-limited clinical trials.13,26 However, no head-to-head clinical trials have compared xanomeline-trospium to FGAs and SGAs; thus, their relative efficacy is still unknown. Nevertheless, a meta-analysis reported that xanomeline-trospium had similar efficacy to aripiprazole, risperidone, and olanzapine.27

Which Treatment-Related Side Effects Interfere With Tolerability of Antipsychotics and Can Precipitate Life-Threatening Conditions?

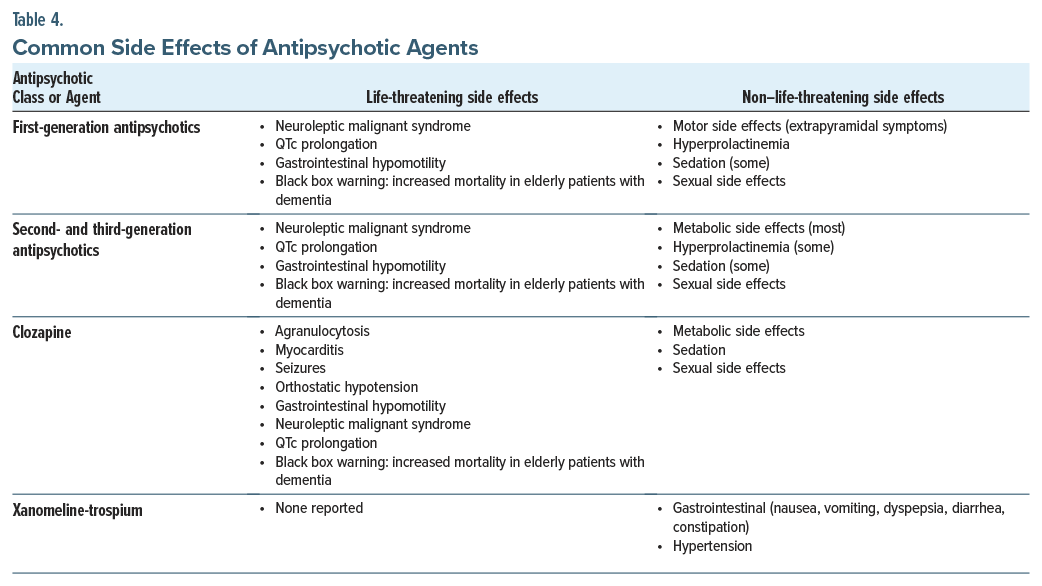

Antipsychotic medications have myriad side effects (Table 4), including several that are potentially lethal (eg, neuroleptic malignant syndrome [NMS], QTc prolongation, and constipation). NMS (characterized by the classic tetrad of fever, rigidity, mental status changes, and autonomic instability) necessitates cessation of all antipsychotic medications and rapid treatment. QTc prolongation is common among antipsychotic agents, particularly FGAs, as well as ziprasidone and iloperidone; it increases the risk of torsades de pointes (“twisting of points”) that can be lethal. Antipsychotics also cause gastrointestinal (GI) hypomotility that can lead to constipation, ileus, and ischemic bowels and progress to obstruction, toxic megacolon, sepsis, and death. The agents most likely to induce these adverse effects are clozapine and quetiapine.28 In addition, clozapine has several rare but life-threatening side effects (eg, agranulocytosis, myocarditis, seizures, and orthostatic hypotension). Moreover, all FGAs and SGAs have an FDA “black box warning” regarding the increased risk of death when used in elderly individuals with dementia.

Dopamine-blocking antipsychotics also have a bevy of other adverse effects that interfere with their tolerability (including metabolic changes and weight gain, after extended use).29 The agents most likely to induce these effects are clozapine and olanzapine, while those with lowest risk include lurasidone,29 ziprasidone,29 lumateperone,30 and xanomeline-trospium.26 FGAs and SGAs can also cause abnormal movements (ie, EPS, including dystonia, akathisia, and parkinsonism), which typically develop early in treatment, especially with use of high-potency FGAs. A late-developing motoric side effect is tardive dyskinesia, which is characterized by irregular but typically irreversible choreiform movements even after the antipsychotic medication has been discontinued. Hyperprolactinemia is also common with use of high-affinity dopamine receptor antagonists, such as the FGAs, risperidone, and paliperidone.23 Low-affinity medications (eg, aripiprazole, clozapine, and quetiapine) are considered prolactin sparing.23 FGAs and SGAs can also cause sexual side effects31 (eg, decreased libido, anorgasmia, and erectile dysfunction), through hyperprolactinemia and D2, α-1, 5-HT2a, and muscarinic receptor antagonism. Many antipsychotics (especially clozapine, olanzapine, and quetiapine) also cause sedation, which can be severe. Finally, some antipsychotics (eg, chlorpromazine) are potent anticholinergics and can induce cognitive dulling.

Xanomeline-trospium, with central muscarinic agonism and peripheral muscarinic antagonism, has a different side effect profile than FGAs and SGAs. Its most common side effects are GI (eg, nausea, vomiting, dyspepsia, diarrhea, and constipation).13,26 It can also cause hypertension.13,26 It is less apt to induce sedation, motor side effects, and weight gain than placebo.13,26 Prolongation of the QTc interval has not been observed with its use.26

What Other Factors Should Be Considered When Selecting an Antipsychotic Agent?

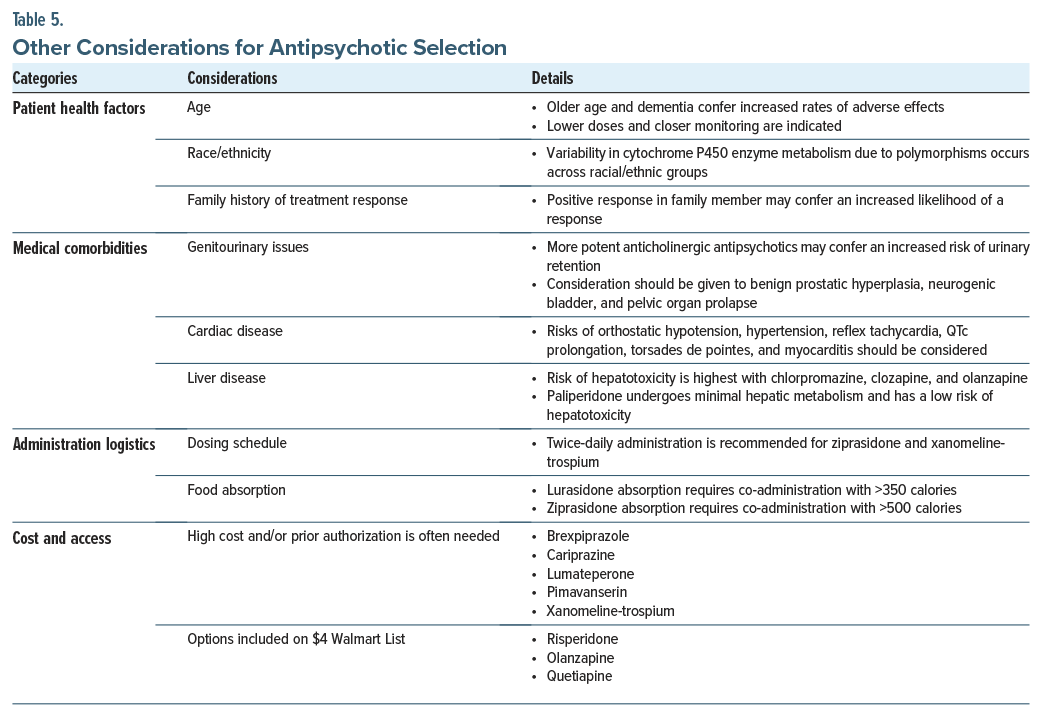

In addition to considering medication efficacy and their side effect profiles, other factors (eg, patient health factors, medical comorbidities, and logistical concerns that affect adherence and access) should be considered when selecting an antipsychotic agent.

Patient health factors include age, race, and family history of treatment response. Regarding age, older adults (especially those with dementia) are at an elevated risk of adverse effects (eg, TD, aspiration events, and mortality in the setting of antipsychotic administration).32 Nonetheless, they remain first-line treatment options for schizophrenia, although lower doses are often necessary, and closer monitoring is warranted. Moreover, race/ ethnicity is associated with a variability in drug response, in part due to polymorphisms of the cytochrome P450 (CYP450) system, which is responsible for much of the metabolism of antipsychotic medications.33 For instance, 5%–10% of Caucasians are CYP450-2D6 poor metabolizers, compared to 1%–2% of Asians and 2%–5% of African Americans.34 While antipsychotic selection should not be based solely on these factors, treatment responses differ among certain demographic groups, which merits dose monitoring and adjustment. Because of this metabolic heterogeneity and therefore the clinical response, a family history of effective treatment with an antipsychotic may guide drug selection.

Medical comorbidities (eg, benign prostatic hypertrophy [BPH], a cardiac history, or liver disease) should also be considered when selecting an antipsychotic. For example, highly anticholinergic antipsychotics should be used cautiously in those with medical problems that increase the risk of urinary retention.35 In individuals with BPH or pelvic organ prolapse, the addition of chlorpromazine, clozapine, olanzapine, or xanomeline-trospium increases the risk of urinary retention. A cardiac history should also be considered during antipsychotic selection due to the propensity of several cardiac conditions to induce orthostatic hypotension, hypertension, reflex tachycardia, QTc prolongation, torsades de pointes, and myocarditis.36 For instance, among patients with baseline conduction abnormalities, ziprasidone (the most QTc-prolonging SGA) may not be preferred over an antipsychotic such as aripiprazole (among the least QTc-prolonging of antipsychotics). Lastly, antipsychotic use poses varying risks of hepatotoxicity and to differing degrees hepatic metabolism.37 Paliperidone, for example, undergoes minimal hepatic metabolism, and reports of liver failure have not been associated with its use, which makes it a potentially preferred antipsychotic agent for those with liver disease.37

Logistical factors around dosing should also be considered due to their impact on treatment adherence. For instance, antipsychotics dosed once daily lead to improved adherence.38 Ziprasidone and xanomeline-trospium are antipsychotics administered twice daily, which may increase the potential for missing doses. Moreover, lurasidone and ziprasidone are the 2 antipsychotics that must be taken with meals (having 350 and 500 calories, respectively); if not taken properly, absorption may be hindered, thus diminishingefficacy.39,40

The potential for weight gain varies across antipsychotics and should inform medication selection, particularly in patients at risk for metabolic syndrome. Agents such as olanzapine and clozapine carry the highest risk for weight gain and metabolic disturbances, whereas aripiprazole, ziprasidone, and lurasidone typically have lower risks. In addition, the availability of LAI formulations (eg, risperidone, paliperidone, aripiprazole, and olanzapine) can enhance medication adherence, especially in patients who struggle with maintaining consistent oral medication schedules.

Lastly, many newer antipsychotics (eg, brexpiprazole, cariprazine, lumateperone, pimavanserin, and xanomeline-trospium) tend to be costly or require prior authorization for insurance coverage.41 By way of contrast, several generic antipsychotics (eg, risperidone, olanzapine, and quetiapine) can be made affordable through programs such as the Walmart $4 List (Table 5).42

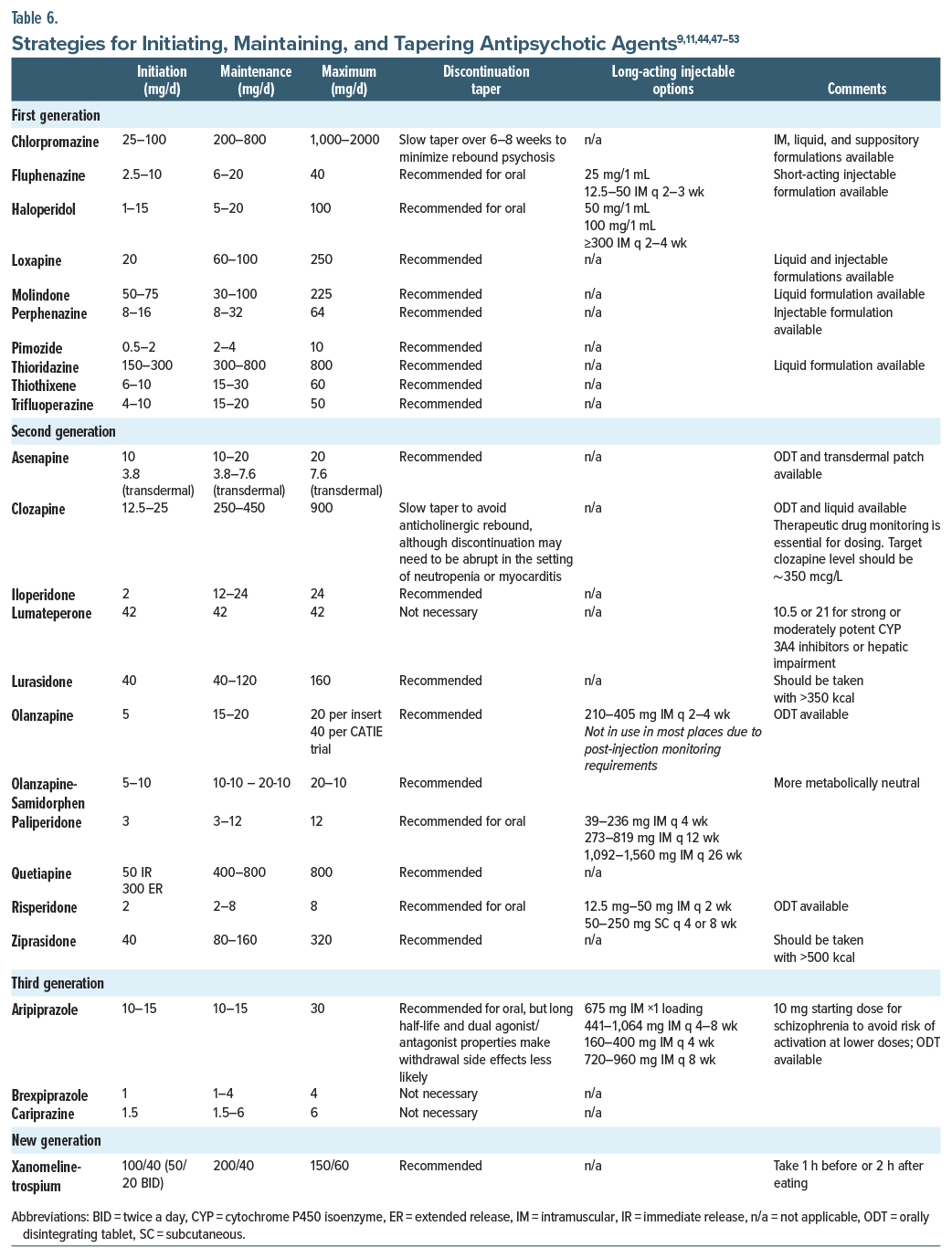

How Should Dosing Be Initiated, Titrated, Maintained, Tapered, and Discontinued?

In general, it is best to “start low and go slow” when initiating any antipsychotic agent. However, starting at a higher dose should be considered when managing an acute psychotic episode, when lower doses of certain medications are activating (eg, aripiprazole), and when patients are unlikely to accept gradual dose titrations. Patient age and the site of administration (inpatient or outpatient setting) also inform initial dosing decisions. Older adults and individuals treated in outpatient settings may require lower initial doses and more gradual titration, while inpatient settings often allow for closer monitoring and more aggressive dosing when clinically indicated. After establishing that an agent is tolerable (eg, anaphylaxis or dystonia has not developed), the dose should be titrated gradually (while monitoring for adverse effects) until an effective dose has been reached. Throughout the treatment course, symptoms should be assessed while partaking in therapeutic drug monitoring (TDM). TDM is especially helpful when clozapine is being prescribed, as there is a threshold above which clozapine is effective (350 mcg/L) for most people and an upper limit (1,000 mcg/L) above which the risk of seizures may outweigh the drug’s antipsychotic benefits.43 Of note, clozapine blood levels are significantly reduced by cigarette smoking by virtue of its effect on the CYP1A2 pathway, while clozapine doses should be reduced during periods of smoking cessation.

After achieving symptom remission, or at least symptom reduction, the American Psychiatric Association recommends ongoing treatment with antipsychotic medication.44 The goal of maintenance treatment is to prevent relapse (by using the lowest effective medication dose). Moreover, treatment failure should not be declared until a patient has been taking the medication for an adequate duration. When nonadherence arises in those with schizophrenia-spectrum illnesses, use of LAI antipsychotics can ensure medication adherence, thereby reducing the risk of relapse and rehospitalization. Using LAI antipsychotics should be presented early in the treatment course as a viable and potentially preferred option; moreover, some patients prefer to avoid taking a daily pill.45

Tapering of medication doses, whether it is at the patient’s insistence or while changing medications, should be done gradually to minimize withdrawal symptoms. The tapering schedule should consider the medication’s half-life and receptor affinity. Medications with shorter half-lives (eg, quetiapine) require slower tapering to avoid withdrawal symptoms, while those with long half-lives (eg, aripiprazole) can typically be tapered more rapidly. In addition, slow and gradual tapering is especially important for strong D2-blocking medications (eg, haloperidol or risperidone), particularly when lowering from low dosages, to prevent withdrawal dyskinesia and psychotic decompensation. Abrupt reduction of clozapine dosing can precipitate a cholinergic crisis, as well as rebound psychosis or catatonia.46 Close monitoring for symptom re-emergence and manifestations of drug withdrawal is essential; therefore, having a relapse prevention plan or a wellness recovery action plan can help a team to mitigate risks. Unfortunately, some patients are unable to recognize their early warning signs and symptoms of relapse during a psychotic decompensation.9 Therefore, clinicians should discuss this concept with patients and their family members or support systems early in treatment and prepare a monitoring plan (Table 6).

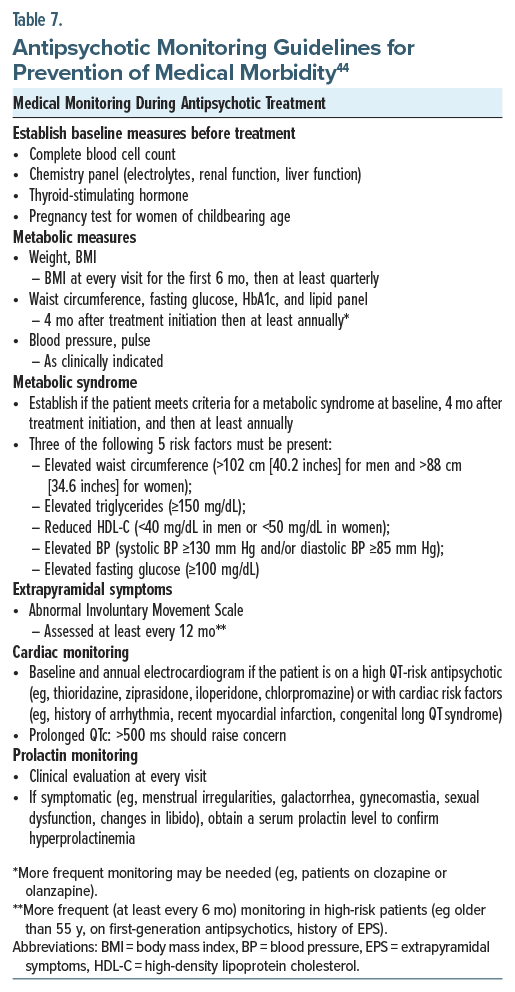

What Type of Monitoring Is Needed for Antipsychotic Agents?

Table 744 summarizes recommended guidelines for monitoring patients on antipsychotic medications, underscoring the importance of integrated psychiatric and medical care in managing schizophrenia and reducing associated health risks. Routine and systematic monitoring is critical for identifying and managing medical complications associated with antipsychotic use. Approximately 40% of patients with schizophrenia develop a metabolic syndrome, which significantly increases their cardiovascular risk compared to those in the general population. Thus, regular surveillance of modifiable cardiovascular risk factors (eg, smoking status, dyslipidemia, diabetes, and weight gain) is essential.48

Baseline evaluations (before starting an antipsychotic) should include a complete blood count, a basic metabolic panel (with electrolyte levels, renal and hepatic function), thyroid-stimulating hormone level, and a pregnancy test for women of childbearing potential. Metabolic assessments (eg, weight, BMI, waist circumference, fasting glucose, hemoglobin A1C (HbA1c), lipid panels, and blood pressure) must be performed routinely.

BMI should be assessed at every clinical visit during the initial 6 months of antipsychotic treatment, followed by quarterly checks. Patients with a BMI ≥30 kg/m2 or BMI ≥27 kg/m2 with at least 1 weight-related comorbidity should be considered for GLP-1 agonist therapy (eg, tirzepatide, semaglutide) for weight management. Waist circumference, fasting glucose, HbA1c, and lipid panels should be measured initially and 4 months after treatment initiation, thereafter at least annually. More frequent monitoring is advised for patients started on high-risk antipsychotics (eg, clozapine and olanzapine).44

Metabolic syndrome—defined by the presence of at least 3 of the following: increased waist circumference, triglycerides greater or equal to 150 mg/dL, reduced high-density lipoprotein cholesterol (less than 40 mg/mL in men and less than 50 mg/dL in women), elevated blood pressure (greater or equal to 130/85 mm Hg), and a fasting glucose (greater or equal to 100 mg/dL)— should be checked at baseline, 4 months after initiation, and annually thereafter.44

EPS require monitoring via the Abnormal Involuntary Movement Scale at least annually, at a higher frequency (every 6 months) for high-risk patients, including those over the age of 55 years, those receiving FGAs, or those with prior EPS.44 Patients prescribed antipsychotics that are known to prolong the QT interval (eg, thioridazine, ziprasidone, iloperidone, and chlorpromazine) or those with existing cardiac risk factors should have an electrocardiogram performed at baseline and annually thereafter. QTc intervals that exceed 500 ms are generally considered as clinically significant, although no absolute QTc threshold mandates the discontinuation of an antipsychotic.44 Individualized clinical decisions should be guided by a comprehensive risk-benefit assessment, particularly considering patient-specific risk factors.

Finally, prolactin-related symptoms should be evaluated at each visit. Serum prolactin levels should be measured when symptoms that suggest hyperprolactinemia (eg, menstrual disturbances, galactorrhea, gynecomastia, sexual dysfunction, or alteration of libido) are present. When elevated, switching to a prolactin-sparing antipsychotic should be considered via shared decision-making.44

What Happened to Mr A?

Upon Mr A’s inpatient admission, he underwent a comprehensive psychiatric evaluation and was started on xanomeline-trospium at a dose of 50-20 mg twice daily. Laboratory results (including a comprehensive metabolic panel, liver function test, and tests of renal function) were within normal limits, as were his vital signs. He experienced mild nausea and diarrhea, which resolved after 7 days. After tolerating the initial dosage well and showing partial improvement of his psychotic symptoms over the next 2 weeks, his dosage was increased to 100-20 mg twice daily. At this dose, his psychotic symptoms abated without inducing significant adverse effects. After 4 weeks of hospitalization, Mr A was discharged home.

Following discharge, Mr A continued to receive xanomeline-trospium, and he was monitored closely. After about 5 months, he was substantially improved, and his prolactin level (10 ng/mL) normalized, with resolution of gynecomastia and associated distress. He also reported that his cognition and attention improved, which allowed him to engage in cognitively demanding activities (eg, reading and watching movies). He denied having EPS, including akathisia. In addition, he gradually lost weight, which alleviated his metabolic issues. Mr A remains stable on xanomeline-trospium, with regular outpatient monitoring.

CONCLUSION

Although antipsychotics remain relatively blunt tools that often modulate biology downstream of a poorly understood underlying pathophysiology, they offer substantial benefits for many individuals with psychotic disorders, and their use remains the standard of care in psychiatry. In addition, antipsychotics are commonly used off-label for managing acute behavioral issues and psychosis associated with dementia, delirium, substance use, and developmental disorders across inpatient, long-term care, and outpatient settings. The unifying mechanism of action among antipsychotics has been based on dopamine D2 receptor blockade (ie, reduction of dopaminergic activity along the mesolimbic circuit at the striatum is likely the mechanism by which antipsychotics treat delusions, hallucinations, and disorganization). Two antipsychotics have little to no activity at the D2 receptor: clozapine and xanomeline-trospium. Off-target dopamine blockade, however, is also responsible for side effects (eg, EPS) and worsening negative symptoms.

Antipsychotic medications have myriad side effects, including several that are potentially lethal (eg, NMS, QTc prolongation, and GI hypomotility [that can lead to ileus, ischemic bowels, and sepsis], agranulocytosis, myocarditis, and seizures). FGAs and SGAs can also cause abnormal movements (ie, EPS, including dystonia, akathisia, parkinsonism), which typically develop early in treatment, especially with use of high-potency FGAs, as well as TD (a late-developing motoric side effect). Although many newer antipsychotics (eg, brexpiprazole, cariprazine, lumateperone, pimavanserin, and xanomeline-trospium) tend to be costly or require prior authorization for insurance coverage, they may be preferred after undergoing a personalized cost-benefit analysis.

Article Information

Published Online: October 28, 2025. https://doi.org/10.4088/PCC.25f03983

© 2025 Physicians Postgraduate Press, Inc.

Submitted: April 8, 2025; accepted June 17, 2025.

To Cite: Lim CS, Morfin Rodriguez A, Donovan AL, et al. Choosing a pharmacologic strategy for those with a psychotic illness: balancing efficacy, tolerability, and cost. Prim Care Companion CNS Disord 2025;27(5):25f03983.

Author Affiliations: Department of Psychiatry, Massachusetts General Hospital and Harvard Medical School, Boston, Massachusetts (Lim, Morfin Rodriguez, Donovan, Daneshvari, Stern); Department of Psychiatry, Massachusetts General Hospital, Boston, Massachusetts (MacLaurin). Lim, Morfin Rodriguez, Donovan, MacLaurin, and Daneshvari are co-first authors; Stern is senior author.

Corresponding Author: Carol S. Lim, MD, Department of Psychiatry, Massachusetts General Hospital, 151 Merrimac St, 4th floor, Boston, MA 02114 ([email protected]).

Relevant Financial Relationships: None.

Funding/Support: None.

Clinical Points

- Compared to all other antipsychotics, clozapine has superior efficacy and is the only antipsychotic that is US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) approved for treatment-resistant schizophrenia.

- Long-acting injectables have improved efficacy compared to oral formulations, an observation that is likely related to their enhanced treatment adherence.

- The newest antipsychotic agent, xanomeline-trospium (Cobenfy, Kar-XT), has a novel mechanism of action, acting upstream from the dopamine receptor targeted by the first-generation antipsychotics (FGAs) and second-generation antipsychotics (SGAs).

- All FGAs and SGAs have an FDA “black box warning” regarding the increased risk of death when used in elderly individuals with dementia.

- Throughout the treatment course, symptoms should be assessed while partaking in therapeutic drug monitoring.

References (53)

- Blackman G, Byrne R, Gill N, et al. How common is secondary psychosis? Estimates from a systematic review and meta-analysis. World Psychiatry. 2025;24(1):145–146. PubMed CrossRef

- Kosten TR, O’Connor PG. Management of drug and alcohol withdrawal. N Engl J Med. 2003;348(18):1786–1795. PubMed

- de TB. Epilepsy and psychosis. Rev Neurol. 2024;180(4):298–307. PubMed

- Hébert J, Muccilli A, Wennberg RA, et al. Autoimmune encephalitis and autoantibodies: a review of clinical implications. J Appl Lab Med. 2022;7(1):81–98. PubMed

- Cui L, Li S, Wang S, et al. Major depressive disorder: hypothesis, mechanism, prevention and treatment. Signal Transduct Target Ther. 2024;9(1):30. PubMed CrossRef

- Geller J. The Rise and Demise of America’s Psychiatric Hospitals: a Tale of Dollars Trumping Sense. American Psychiatric Publishing, Inc.;2019.

- Davis L, Fulginiti A, Kriegel L, et al. Deinstitutionalization? Where have all the people gone?. Curr Psychiatry Rep. 2012;14(3):259–269. PubMed CrossRef

- Ozarin LD, Feldman S. Implications for health service delivery: the community mental health centers amendments of 1970. Am J Public Health. 1971;61(9):1780–1784. PubMed CrossRef

- Freudenreich O. Psychotic disorders. Springer;2020.

- Kane J, Honigfeld G, Singer J, et al. Clozapine for the treatment-resistant schizophrenic. A double-blind comparison with chlorpromazine. Clin Trial Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1988 Sep;45(9):789–96.

- Meyer JM, Stahl SM. The Clozapine Handbook: Stahl’s Handbooks. Cambridge University Press;2019. CrossRef

- Westman J, Eriksson S, Gissler M, et al. Increased cardiovascular mortality in people with schizophrenia: a 24-year national register study. Epidemiol Psychiatr Sci. 2018;27(5):519–527. PubMed CrossRef

- Kaul I, Sawchak S, Correll CU, et al. Efficacy and safety of the muscarinic receptor agonist KarXT (xanomeline–trospium) in schizophrenia (EMERGENT-2) in the USA: results from a randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled, flexible-dose phase 3 trial. Lancet. 2024;403(10422):160–170. PubMed CrossRef

- Paul SM, Yohn SE, Brannan SK, et al. Muscarinic receptor activators as novel treatments for schizophrenia. Biol Psychiatry. 2024;96(8):627–637. PubMed CrossRef

- Luvsannyam E, Jain MS, Pormento MKL, et al. Neurobiology of schizophrenia: a comprehensive review. Cureus. 2022;14(4):e23959. PubMed CrossRef

- Potkin SG, Kane JM, Correll CU, et al. The neurobiology of treatment-resistant schizophrenia: paths to antipsychotic resistance and a roadmap for future research. NPJ Schizophr. 2020;6(1):1. PubMed CrossRef

- Kaar SJ, Natesan S, Mccutcheon R, et al. Antipsychotics: mechanisms underlying clinical response and side-effects and novel treatment approaches based on pathophysiology. Neuropharmacology. 2020;172:107704. PubMed CrossRef

- Meyer JM. How antipsychotics work in schizophrenia: a primer on mechanisms. CNS Spectr. 2025;30(1):e6. CrossRef

- Carbon M, Correll CU. Thinking and acting beyond the positive: the role of the cognitive and negative symptoms in schizophrenia. CNS Spectr. 2014;19(suppl 1): 38–53. PubMed CrossRef

- Németh G, Laszlovszky I, Czobor P, et al. Cariprazine versus risperidone monotherapy for treatment of predominant negative symptoms in patients with schizophrenia: a randomised, double-blind, controlled trial. Lancet. 2017; 389(10074):1103–1113. PubMed

- Martins-Correia J, Fernandes LA, Kenny R, et al. Cariprazine in the acute treatment of unipolar and bipolar depression: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Affect Disord. 2024;362:297–307. PubMed CrossRef

- Krause M, Zhu Y, Huhn M, et al. Antipsychotic drugs for patients with schizophrenia and predominant or prominent negative symptoms: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Eur Arch Psychiatry Clin Neurosci. 2018;268(7):625–639. PubMed CrossRef

- Huhn M, Nikolakopoulou A, Schneider-Thoma J, et al. Comparative efficacy and tolerability of 32 oral antipsychotics for the acute treatment of adults with multi-episode schizophrenia: a systematic review and network meta-analysis. Lancet. 2019;394(10202):939–951. PubMed CrossRef

- Subotnik KL, Casaus LR, Ventura J, et al. Long-acting injectable risperidone for relapse prevention and control of breakthrough symptoms after a recent first episode of schizophrenia: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA Psychiatry. 2015;72(8):822–829. PubMed CrossRef

- Taipale H, Mittendorfer-Rutz E, Alexanderson K, et al. Antipsychotics and mortality in a nationwide cohort of 29,823 patients with schizophrenia. Schizophr Res. 2018;197:274–280. PubMed CrossRef

- Kaul I, Sawchak S, Walling DP, et al. Efficacy and safety of xanomeline-trospium chloride in schizophrenia: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA Psychiatry. 2024;81(8):749–756. PubMed CrossRef

- Wright AC, McKenna A, Tice JA, et al. A network meta-analysis of KarXT and commonly used pharmacological interventions for schizophrenia. Schizophr Res. 2024;274:212–219. PubMed CrossRef

- Chen H-K, Hsieh C-J. Risk of gastrointestinal Hypomotility in schizophrenia and schizoaffective disorder treated with antipsychotics: a retrospective cohort study. Schizophr Res. 2018;195:237–244. PubMed CrossRef

- Burschinski A, Schneider-Thoma J, Chiocchia V, et al. Metabolic side effects in persons with schizophrenia during mid to long term treatment with antipsychotics: a network meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. World Psychiatry. 2023;22(1):116–128. PubMed CrossRef

- McIntyre RS, Kwan AT, Rosenblat JD, et al. Psychotropic drug–related weight gain and its treatment. Am J Psychiatry. 2024;181(1):26–38. PubMed CrossRef

- Souaiby L, Kazour F, Zoghbi M, et al. Sexual dysfunction in patients with schizophrenia and schizoaffective disorder and its association with adherence to antipsychotic medication. J Ment Health. 2020;29(6):623–630. PubMed CrossRef

- Alexopoulos GS, Streim J, Carpenter D, et al. Using antipsychotic agents in older patients. J Clin Psychiatry. 2004;65(suppl 2):5–104. PubMed

- McGraw J, Waller D. Cytochrome P450 variations in different ethnic populations. Expert Opin Drug Metab Toxicol. 2012;8(3):371–382. PubMed CrossRef

- LLerena A, Naranjo MEG, Rodrigues-Soares F, et al. Interethnic variability of CYP2D6 alleles and of predicted and measured metabolic phenotypes across world populations. Expert Opin Drug Metab Toxicol. 2014;10(11):1569–1583. PubMed CrossRef

- Verhamme KM, Sturkenboom MC, Stricker BHC, et al. Drug-induced urinary retention: incidence, management and prevention. Drug Saf. 2008;31(5):373–388. PubMed CrossRef

- Khasawneh FT, Shankar GS. Minimizing cardiovascular adverse effects of atypical antipsychotic drugs in patients with schizophrenia. Cardiol Res Pract. 2014;2014:273060. PubMed CrossRef

- Gunther M, Dopheide JA. Antipsychotic safety in liver disease: a narrative review and practical guide for the clinician. J Acad Consult Liaison Psychiatry. 2023;64(1):73–82. PubMed CrossRef

- Pfeiffer PN, Ganoczy D, Valenstein M. Dosing frequency and adherence to antipsychotic medications. Psychiatr Serv. 2008;59(10):1207–1210. PubMed CrossRef

- Preskorn S, Ereshefsky L, Chiu YY, et al. Effect of food on the pharmacokinetics of lurasidone: results of two randomized, open-label, crossover studies. Hum Psychopharmacol. 2013;28(5):495–505. PubMed CrossRef

- Citrome L. Using oral ziprasidone effectively: the food effect and dose-response. Adv Ther. 2009;26(8):739–748. PubMed CrossRef

- Maryland Medicaid. Maryland Medicaid Mental Health Drug List. Maryland Medicaid Pharmacy Program. Accessed April 3, 2025. https://mhdl.pharmacyservices.conduent.com/MHDL/pubtheradetail.do?id=24

- Walmart Apollo, LLC. Guide to Low-Cost Prescriptions Starting at $4. Walmart; 2025. Accessed April 3, 2025. https://i5.walmartimages.com/dfw/4ff9c6c9-119c/k2-_c3e2f451-7a63-414e-aac2-e3defc13ef60.v1.pdf

- Siskind D, Sharma M, Pawar M, et al. Clozapine levels as a predictor for therapeutic response: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 2021;144(5):422–432. PubMed CrossRef

- American Psychiatric Association. The American Psychiatric Association Practice Guideline for the Treatment of Patients With Schizophrenia. 3rd ed. American Psychiatric Association; 2020. Accessed April 3, 2025. https://psychiatryonlineorg/doi/book/10.1176/appi.books.9780890424841

- Kane JM, Schooler NR, Marcy P, et al. Effect of long-acting injectable antipsychotics vs usual care on time to first hospitalization in early-phase schizophrenia: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA Psychiatry. 2020;77(12):1217–1224. PubMed CrossRef

- Blackman G, Oloyede E, Horowitz M, et al. Reducing the risk of withdrawal symptoms and relapse following clozapine discontinuation-is it feasible to develop evidence-based guidelines?. Schizophr Bull. 2022;48(1):176–189. PubMed CrossRef

- Leucht S, Crippa A, Siafis S, et al. Dose-response meta-analysis of antipsychotic drugs for acute schizophrenia. Am J Psychiatry. 2020;177(4):342–353. PubMed CrossRef

- Lim CS, Paudel S, Holt DJ, et al. Psychosis and schizophrenia. In: Stern TA, Wilens TE, Fava M, eds. Massachusetts General Hospital Comprehensive Clinical Psychiatry. 3rd ed. Elsevier;2025:305–320.

- Freudenreich O, Stern TA. Antipsychotic drugs. In: Stern TA, Fava M, eds. Learning About Psychopharmacology: A Programmed Text for Multidisciplinary Learners. Massachusetts General Hospital Psychiatry Academy;2023:145–206.

- Paudel S, Lim C, Freudenreich O. Antipsychotic drugs. In: Stern TA, Wilens TE, Fava M, eds. Massachusetts General Hospital Comprehensive Clinical Psychiatry. 3rd ed. Elsevier;2025:555–569.

- Paudel S, Lim C, Freudenreich O. Antipsychotic drugs. In: Stern TA, Camprodon JA, Fava M, eds. Massachusetts General Hospital Psychopharmacology and Neurotherapeutics. 2nd ed. Elsevier;2025:85–99.

- Lim C, Donovan AL, Freudenreich O. Patients with psychosis. In: Stern TA, Beach S, Smith FA, et al, eds. Massachusetts General Hospital Handbook of General Hospital Psychiatry. 8th ed. Elsevier;2025:171–192.

- 53 Stahl SM. Stahl’s Essential Psychopharmacology Prescriber’s Guide. 6th ed. Cambridge University Press;2017.

Enjoy this premium PDF as part of your membership benefits!