Abstract

Objective: Physicians inevitably observe adverse patient outcomes, including death. When these events occur, physicians may be prone to feelings of undeserved guilt. Such feelings may lead to moral injury and contribute to burnout and suicide. We examine examples of physician guilt in television and movies and identify examples of cognitive distortions to help readers gain insight into their own potential feelings of guilt.

Methods: Searches on Google and ChatGPT were performed for “movies + physician guilt,” “television + physician guilt,” and “popular media + physician trauma.” Results were reviewed for 5 cognitive distortions derived from cognitive-behavioral therapy. Additional media examples were added from the authors’ own knowledge base. Of the 4 movies and 6 television episodes found with examples of physician guilt, 7 were chosen and considered through the lens of cognitive distortions.

Results: Multiple examples of cognitive distortions were found that can derive from and contribute to feelings of guilt in physicians. Systemically deconstructing and identifying these distortions can allow one to challenge and replace them with more accurate thoughts, a process known as cognitive restructuring. Looking for examples in popular media is a resource for doing so, since it allows physicians to view situations similar to those that they experience from the perspective of a third party.

Conclusion: Comparing thoughts and feelings to characters in media can help us understand feelings of undeserved guilt. This can inform physicians’ self-reflection, allowing them to consider and mitigate difficult experiences, thoughts, and feelings that may otherwise adversely affect wellness.

Prim Care Companion CNS Disord 2025;27(5):24m03905

Author affiliations are listed at the end of this article.

Physicians of all specialties will invariably observe adverse outcomes, including minor to severe medication adverse effects, injuries ranging from minor lacerations to dismemberment, and death. When these events occur, physicians are potentially prone to feelings of guilt. Outside of medicine, guilt is a common theme in cultural works ranging from Sophocles’ Oedipus, who blinds himself in a fit of guilt upon learning of his previously obscured crimes, to Shakespeare’s Lady Macbeth, who is rent with visions stemming from her complicity in murder. In these works, guilt is incapacitating and leads to irrational maladaptive responses. Clinicians may recognize this incapacitating nature of guilty feelings as something they have seen in their patients, but they also need to recognize the deleterious effects that feelings of guilt can have on them as clinicians.

Diverse models have been formulated to explain guilt. In psychoanalysis, guilt is characterized as a conflict between the id, ego, and superego. In evolutionary psychology, it is seen as a survival mechanism essential in maintaining interpersonal relationships.1 Guilt refers to the feeling of being “less than” for failing to live up to self-expectations. Such expectations can range on a spectrum of being reasonable to unrealistic. The former has been termed natural guilt, and the latter has been termed maladaptive guilt. A child feels guilty after not studying for a failed test, while a mother blames herself for buying a bus ticket for her son and then the bus crashes. Both examples can be described as guilt even though the fundamental reasons behind the feeling may differ. Much of the focus in the literature centers around maladaptive guilt. However, natural guilt is also important, as it exists as an innate function to prevent the repetition of past mistakes.1

While guilt can be a normal emotion or a feature of diverse psychiatric disorders, including, for example, major depressive disorder and psychosis, maladaptive guilt is so prominent in posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) that evidence-based psychotherapeutic treatment protocols have been developed that include tools to assist patients in processing their feelings of guilt.2 Cognitive processing therapy, for example, is a type of cognitive-behavioral therapy (CBT) that addresses cognitive distortions following a trauma and the ways that these contribute to problematic behaviors and emotions, including posttraumatic guilt. Cognitive distortions are inaccurate and unhelpful thoughts that adversely affect emotions and behaviors. However, feelings of guilt are not exclusive to those suffering from PTSD. Adverse medical events experienced from the viewpoint of the treating doctor can also be experienced as traumatic, and, so, the concepts are likely to be applicable to doctors as well. Painful feelings of guilt can and do develop outside of pathological processes, and, so, even physicians who are not suffering from diagnosable PTSD may be able to benefit from understanding how guilt can develop in the course of their work.3

In this article, we examine relevant movies and television shows to highlight such cognitive distortions and provide physicians with tools to assist them in understanding and allaying undeserved feelings of guilt. The examples that we extracted from popular media are used to shed light on the cognitive distortions that often underlie the development of maladaptive feelings of guilt. Understanding and correcting cognitive distortions is a central method used throughout many CBT protocols. CBT treatments highlight several types of cognitive distortions that contribute to maladaptive feelings of guilt. Examples include outcome-based reasoning, hindsight bias, personalization, emotional reasoning, and difficulty differentiating between intention, responsibility, and the unforeseeable.4

Outcome-based reasoning is a cognitive distortion that can contribute to guilt. Outcome-based reasoning involves the erroneous belief that the world must be inherently fair. Outcome-based reasoning leads individuals to blame themselves for unfavorable outcomes, assuming that a bad outcome must be a result of poor decision-making. However, this is an oversimplification. Not all negative outcomes stem from poor decisions, and outcome-based reasoning can contribute to unwarranted guilt.

Hindsight bias entails thinking about what could have or should have been done to prevent or stop a past event. In hindsight, one can know the lottery numbers, but a lottery is still a game of chance. In hindsight, one can say, “I should have known that was going to happen because then I could have acted differently to prevent it,” but thinking it does not indicate one could actually have changed the past. Hindsight does not incorporate limited time to make decisions, imperfect memory of events, the probability of different outcomes than what occurred, competing variables, lack of familiarity at the time with a situation to which one never had the opportunity to be exposed, limited choices in the past circumstance, or a lack of skills at the time to deal with that past situation. Hindsight itself can cause memory distortion. Prior to the event occurring, there may have been no objective basis to make a prediction.

Personalization involves placing full blame on oneself for a situation that actually involved factors beyond one’s control. This cognitive distortion can reflect the concept of a locus of control, as those who have a strong internal focus can have difficulty wrestling with the fact that failure may not be a reflection of their actions.

Related to and contributing to personalization are difficulties differentiating between intention, responsibility, and the unforeseeable, another cognitive distortion, and confusing the 3 can lead to maladaptive guilt. Three hypothetical examples follow to assist in recognizing the differences between them:

- A person is angry at a neighbor. He waits for the neighbor to go to work and then intentionally drives his car through the neighbor’s garage door to punish him for perceived wrongs. There is intent to harm, and the driver is clearly responsible for damage that ensues.

- While talking on a cellphone, a speeding driver loses control of his vehicle. The car slams into a house next to the road. The police might determine no intent to cause property damage, but the driver does bear responsibility for the damage, as he was both speeding and distracted by his own choice to use a cellphone while driving. Legal charges might ensue, but some recognition of the lack of intent would temper the ramifications relative to the driver who intentionally drove his car into another person’s home.

- A slow careful driver on her way home accidentally hits a patch of black ice on a poorly lit road. Her car slides off the road into a house. The police might determine that there was no intent, no responsibility, and that this was an unpredictable event. Therefore, no legal charges stem from the event. The driver, on the other hand, might feel guilty because they have difficulty recognizing that they had no intent, responsibility, or ability to predict such a random event.

Emotional reasoning occurs when someone reasons something about the world based on a feeling that precedes the thought. For example, someone who feels scared might reason that they are in danger because fear indicates danger, someone who feels proud might reason that they did something exceptionally well because they feel proud, or someone who feels shame might reason that they are inadequate because they feel ashamed. In the case of guilt, someone might reason that they did something wrong because they feel guilty.

By elucidating these cognitive distortions, readers may gain an understanding of physician guilt, which may be helpful in engendering empathy for themselves and their colleagues as well as in processing common deleterious responses to the challenges they face working in health care. Of note, we also would point out that self-help is not always sufficient, and physicians in distress may benefit from psychotherapy.

METHODS

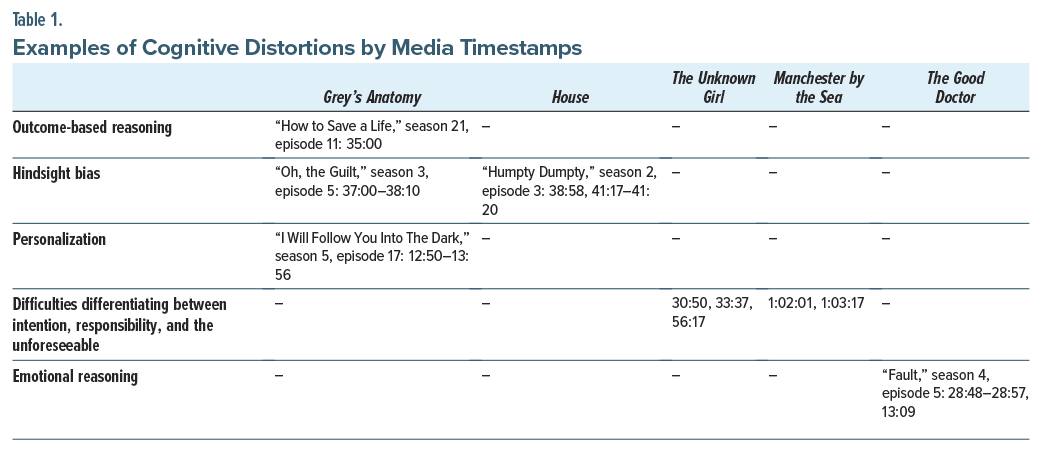

Teaching through film has been recognized as a technique that may improve attention and retention and allow learning, even about potentially painful topics, in a more enjoyable manner.5 We compiled a selection of movies and television episodes that depict physician guilt and highlighted the cognitive distortions that can be present. Physician guilt was examined first to find examples, and cognitive distortions were then identified within each. Multiple searches were done in Google and ChatGPT with the keywords “movies + physician guilt,” “television + physician guilt,” and “popular media + physician trauma” to create an ample sample size. Additional examples were added from the authors’ knowledge base. Twelve unique movies and television episodes were found to depict physician guilt following this review. Seven of these were found to highlight the aforementioned cognitive distortions (outcome-based reasoning, hindsight bias, personalization, emotional reasoning, and difficulty differentiating between intention, responsibility, and the unforeseeable) that can manifest in maladaptive guilt. Our team of authors watched these 7 episodes and movies from start to finish. We recorded timestamps for when these cognitive distortions were prominently on display (Table 1) and analyzed their basis, portrayal, and how they can be deleterious.

As available, we focused on more recent media that portrayed working doctors, as these examples portrayed physicians in circumstances similar to those that current clinicians may encounter. Of note, to better contextualize one type of cognitive distortion (difficulty differentiating between intention, responsibility, and the unforeseeable), the film Manchester by the Sea was also included. It does not portray physicians but does have several useful depictions of guilt. Other films such as John Q, The Doctor, and Awakenings are notable older examples of physician guilt that could also potentially be explored. However, for the sake of brevity, these (and 2 other examples) were not included, as they demonstrated redundant examples of cognitive distortions that were already listed previously.

RESULTS

An example of outcome-based reasoning was found in the episode of Grey’s Anatomy “How to Save a Life” (S21E11, 2015). Grey’s Anatomy, a television drama, follows the lives of medical residents as they become attendings at Seattle Grace Hospital. In this episode, a patient dies because a computed tomography (CT) head scan is not performed in a timely manner. One of the doctors responsible for deciding not to send the patient for the scan blames herself for his death. While she did initially advocate for obtaining a head CT, other members of the treatment team pressured her out of it. After realizing that he will die and that the failure to obtain a CT scan was potentially related to this outcome, she states, “He’s going to die because I was not a good enough doctor to keep him alive” (35:00). This serves as an example of outcome-based reasoning in that she starts with the outcome (“He’s going to die…”) and forms a conclusion about her own inadequacy as a doctor as a result. Although she participated in the decision-making that failed to obtain the CT scan, an objective viewer of the episode might surmise that she takes too much responsibility for this outcome, perhaps beyond that which she deserves, contributing to feelings of guilt. In reality, there were multiple inputs to the patient’s passing. Her conclusion is overly broad and so undeserved. Other team members’ opinions played into the decision, he had other injuries, and it could not be assured that he might not have died anyway. Additionally, this one outcome does not define her quality as a physician. She is overgeneralizing from a catastrophic outcome to make global conclusions about her own self-worth as a doctor.

Hindsight bias is seen in the House episode “Humpty Dumpty” (S2E3, 2005). House follows the titular Dr House as he leads a team of diagnosticians in identifying unique presentations of diseases. In the episode, Dr Cuddy feels bad for misdiagnosing a patient with disseminated intravascular coagulation, when in reality it was a case of psittacosis. The late diagnosis forced them to amputate the patient’s hand due to gangrene. Birds are a primary vector of psittacosis, and the doctor did not know that the patient was exposed to birds, since the patient hid the fact that he worked in a cockfighting ring. Dr Cuddy exhibits hindsight bias when she states in a self-accusatory manner that “if we’d figured it out earlier,” the patient would not have had to lose his hand (38:58).

However, there was no way to suspect bird exposure when the patient was not forthcoming. Recognizing Dr Cuddy’s undeserved feelings of guilt, this observation is made by her physician colleagues who state that “there was no way she could’ve [known]” (41:17–41:20). Similarly, in another episode of Grey’s Anatomy, “Oh, the Guilt” (S3E5, 2006), Dr Webber, a surgeon, demonstrates hindsight bias as he reflects with a resident on a mistake he made as an intern. Dr Webber tells of “a stable cardiac patient who blew out his lung” and died while he was transporting him to the CT scanner (37: 00–38:10). The chief reflects on what could have been done to prevent the death of his patient. If he had placed a chest tube immediately, he believed he could have saved the patient. However, there is no way to objectively know what would have happened in that circumstance.

Personalization also plays a significant role in guilt. In the Grey’s Anatomy episode “I Will Follow You Into the Dark” (S5E17, 2009), Dr Shepherd has a meeting with his lawyers regarding a malpractice lawsuit. During this meeting, Dr Shepherd displays 2 stacks of files. The small pile belongs to cases where his patients survived. The significantly larger pile of files is filled with cases in which his patients died. He faults himself for these “failures,” comparing himself to serial killers like Jeffrey Dahmer, noting that he has killed more people than multiple serial killers combined. Dr Meredith Grey argues that Dr Shepherd needs to consider that the cases in the files are terminal and already had a very low chance of survival. Dr Shepherd, however, takes a chance on these patients. However, he is unable to accept this and states “the big picture is that I’m a murderer” (12:50–13:56). This exemplifies personalization in that Dr Shepherd is blaming himself for an outcome that likely would have occurred regardless.

An example of difficulty differentiating between intention, responsibility, and the unforeseeable is seen in the movie The Unknown Girl (2016). The protagonist, Dr Davin, deals with misplaced guilt after a girl bangs on the clinic doors late at night. She is later found dead. Dr Davin states, “If I opened the door, she’d be alive” (30:50). Even if she did open the door, there is no guarantee the girl would be unharmed. What happened was an unforeseeable event. The girl was not even Dr Davin’s patient. While there is an element of hindsight bias here, a colleague in the film recognized that Dr Davin was having difficulty differentiating between responsibility and the unforeseeable. This colleague stated, “Any court would acquit you for not opening your door that late” (33:37) to console and address the doctor’s misperception. Later in the movie, intent is invoked when Dr Davin opines that “If anyone’s guilty, I am” (56:17) and that perhaps she intentionally made the choice not to open that door for the wrong reasons.

Although it is a nonmedical setting, the movie Manchester by the Sea has a poignant example of the misattribution of intent. The protagonist, Lee Chandler, is burdened with profound guilt following an accident. Lee forgot to put the screen on the fireplace, and his home caught fire, killing his children. His guilt is a central theme of the film. A pivotal scene that encapsulates Lee’s struggle with guilt depicts a police interrogation after the fire. Lee is overwhelmed with remorse and believes he deserves criminal punishment for his role in the accident. The police officer states, “assuming the forensic bears you out, which I’m assuming they will be, Lee, you made a horrible mistake, like a million other people did last night. Not gonna crucify you. It’s not a crime to forget to put the screen on the fireplace” (1:02:01). Upon failing to convince the police to charge him with a crime, Lee attempts to grab a police officer’s gun to render his own punishment (1:03:17).

An example of emotional reasoning is seen in The Good Doctor episode “Fault” (S4E5, 2020) when a resident feels guilty over missing an abdominal aortic aneurysm that eventually ruptures. The Good Doctor is a drama about a surgeon with autism and his interactions with his colleagues and patients. In the episode, a resident says that he “screwed up” by missing the aneurysm, since “that first exam, [he] felt something” (28: 48–28:57). Earlier in the episode, however, he states that “it felt like normal musculature” (13:09). In sum, he feels guilty, and as a result, he starts to create evidence to back up his guilt by stating that he missed a key finding, when in reality his mind created this fact to reconcile his emotions with his own constructed perception of the situation. This situation illustrates how insidious emotional reasoning can be, as by trying to find things that went wrong, the surgeon inadvertently creates a misleading recollection of the event, thus perpetuating harmful cycles of guilt.

DISCUSSION

Guilt is a complex, multifactorial emotion that can be both fueled by and contribute to cognitive distortions. Examining examples in popular media provides a means to understand these distortions. The aversive emotions that accompany certain clinical scenarios can make it challenging for us to approach our own real-life experiences directly. A stepwise, hierarchical exposure to difficult situations is a recognized approach to learning to cope with distortions, and examination of films is a way that doctors struggling with their own experiences can ease into learning to rethink these situations, potentially breaking oppressive cycles of self-persecution. Systematically identifying and challenging these distortions is a crucial first step in moving forward since it allows the distortions to be changed to more accurate thoughts, a process known as cognitive restructuring.5

That said, it should be noted that fiction is fictional and so may not always accurately recapitulate reality. Additionally, not all guilt is undeserved and not all guilt needs to be absolved. If we have done something wrong, guilt may be appropriate. Learning from past mistakes and allowing guilt to guide against future mistakes is also an important lesson that our emotions can teach.6 Physicians should consult with supervisors and peers and potentially undergo psychotherapy should distressing feelings of guilt be persistent, whether deserved, underserved, or of an equivocal nature.

Physicians spend their careers treating others, but sometimes we, too, need healing.7 Our work is lifesaving and fulfilling, but we are also exposed to extremes of human suffering. We attempt to prevent and undo what is sometimes impossible. Illness and death come to everyone eventually, and we cannot invariably stem the inevitable, although our perfectionistic selves wish that we could. The wounds that our patients suffer can render injury to us. Painful feelings such as guilt may be a clue that we have suffered just such a wound, and an understanding of these wounds in our fictional colleagues may serve as a bandage that we can apply to ourselves.

Article Information

Published Online: October 21, 2025. https://doi.org/10.4088/PCC.24m03905

© 2025 Physicians Postgraduate Press, Inc.

Submitted: December 15, 2024; accepted April 14, 2025.

To Cite: Zhang V, Dinar A, Arain F, et al. Cognitive distortions in physician guilt: gaining insight and enhancing wellness through media. Prim Care Companion CNS Disord 2025;27(5):24m03905.

Author Affiliations: Department of Psychiatry, Rutgers New Jersey Medical School, Newark, New Jersey (all authors).

Corresponding Author: Vincent Zhang, MD, MPH, Department of Psychiatry, Rutgers New Jersey Medical School, 185 South Orange Ave, Newark, NJ 07103 ([email protected]).

Relevant Financial Relationships: None.

Funding/Support: None.

Previous Presentation: Poster presented at the American Psychiatric Association Annual Meeting; May 4–8, 2024; New York, New York.

Clinical Points

- Painful feelings such as guilt can occur following negative patient outcomes.

- Guilt, underserved or deserved, can manifest itself in the form of cognitive distortions such as outcome-based reasoning, hindsight bias, personalization, emotional reasoning, and difficulty differentiating between intention, responsibility, and the unforeseeable.

- Identifying and gaining better understanding of cognitive distortions through observing third-party examples in mediums such as film can assist in cognitive restructuring and help alleviate potential physician burnout.

References (7)

- Breggin PR. The biological evolution of guilt, shame and anxiety: a new theory of negative legacy emotions. Med Hypotheses. 2015;85(1):17–24. PubMed CrossRef

- Pugh LR, Taylor PJ, Berry K. The role of guilt in the development of post-traumatic stress disorder: a systematic review. J Affect Disord. 2015;182:138–150. PubMed CrossRef

- Einav S, Shalev AY, Ofek H, et al. Differences in psychological effects in hospital doctors with and without post-traumatic stress disorder. Br J Psychiatry. 2008;193(2):165–166. PubMed CrossRef

- Resick PA, Monson CM, Chard KM. Cognitive Processing Therapy: Veteran/Military Version: Therapist and Patient Materials Manual. Department of Veterans Affairs; 2014.

- Lumlertgul N, Kijpaisalratana N, Pityaratstian N, et al. Cinemeducation: a pilot student project using movies to help students learn medical professionalism. Med Teach. 2009;31(7):e327–e332. PubMed CrossRef

- Firth-Cozens J. Interventions to improve physicians’ well-being and patient care. Soc Sci Med. 2001;52(2):215–222. PubMed CrossRef

- George S, Hanson J, Jackson JL. Physician, heal thyself: a qualitative study of physician health behaviors. Acad Psychiatry. 2014;38(1):19–25. PubMed CrossRef

Enjoy this premium PDF as part of your membership benefits!