Lessons Learned at the Interface of Medicine and Psychiatry

The Psychiatric Consultation Service at Massachusetts General Hospital sees medical and surgical inpatients with comorbid psychiatric symptoms and conditions. During their twice-weekly rounds, Dr Stern and other members of the Consultation Service discuss diagnosis and management of hospitalized patients with complex medical or surgical problems who also demonstrate psychiatric symptoms or conditions. These discussions have given rise to rounds reports that will prove useful for clinicians practicing at the interface of medicine and psychiatry.

Prim Care Companion CNS Disord 2025;27(6):25f03977

Author affiliations are listed at the end of this article.

Have you been unsure about what you can manage and when you should refer your patients to a mental health professional? Have you found it difficult to find a mental health professional with whom you can collaborate? Have you wondered whether communication with a mental health professional about the treatment of your patients will require informed consent from your patients? Have you wondered about different models of integrated mental health care designed to enhance access for your patients? If you have, the following case vignette and discussion should prove useful.

CASE VIGNETTE

Mr C, a 44-year-old man, presented to his primary care physician (PCP) with worsening depression (with a loss of interest in activities, sadness, despondency, fatigue, feelings of guilt, and passive suicidal ideation) and anxiety. He denied having a plan to harm himself and cited several protective factors (including wanting to be available to his 2 children). However, his wife wrote an email to Mr C’s PCP about her concern for her husband, as he was not spending much time out of bed.

His medical history was notable for diabetes, hypertension, and nonalcoholic fatty liver disease, and he was taking sertraline (200 mg/d), clonazepam (0.5 mg nightly for sleep), metformin (500 mg twice daily), dulaglutide (1.5 mg weekly), and lisinopril (20 mg/d). Mr C has been followed by his PCP for the last 8 years. His depressive episodes and generalized anxiety had previously responded to a selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor (SSRI), while his insomnia had improved with alterations in his sleep hygiene and use of a benzodiazepine. At his most recent visit, Mr C’s Generalized Anxiety Disorder-7 (GAD-7) score was 14, and his Patient Health Questionnaire-9 (PHQ-9) score was 21. He had a family history of cardiovascular disease, dementia, and depression.

DISCUSSION

How Has the Training and Delivery of Primary Care Changed Over the Past Several Decades?

Although roughly half of primary care patients have 1 or more psychiatric diagnoses and approximately half of those patients have psychiatric symptoms that lead them to seek medical assessment, training (involving didactics and clinical supervision about psychiatric problems) has remained limited (ie, less than 1 hour/week). Simulation exercises (that guide practitioners to the assessment and treatment of affective, behavioral, and cognitive manifestations) are infrequently introduced, and case-based conferences rarely focus on cases at the interface of medicine and psychiatry. In addition, pressure is often placed on providers to maximize the number of patients seen per session, to shorten the length of each visit, and to maximize the revenue earned by each provider. Moreover, increasingly, physician extenders/nurse practitioners and physician assistants provide care in lieu of visits with PCPs, and their training tends to involve fewer hours than the training of PCPs related to the assessment and management of psychiatric issues.1

When (and why) Should a PCP Consider Consulting With a Mental Health Professional About Their Patient’s Affective, Behavioral, or Cognitive State?

PCPs are often the first health care professionals to see patients who experience symptoms of a mental health disorder. This allows them to play a vital role in early identification (via screening) and management of psychiatric conditions (eg, depression, anxiety, substance use disorders [SUDs], and psychosis) and to determine when specialized care is needed.2

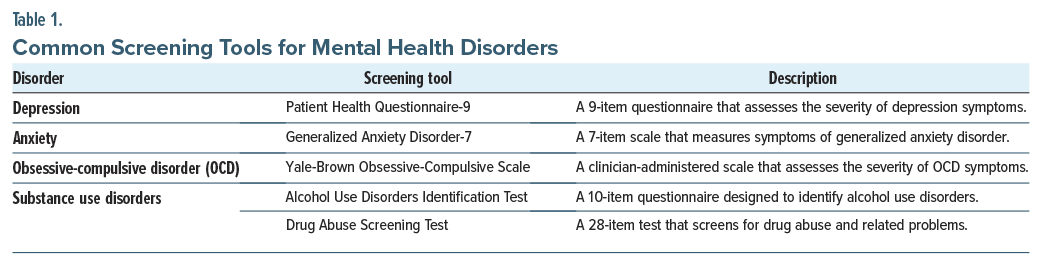

If a patient reports persistent sadness, a lack of interest in daily activities, or significant changes in sleep and appetite, depression may be the cause, and screening tools (eg, the PHQ-9) may be warranted.3 If a patient is experiencing excessive worry, restlessness, or physical symptoms (eg, muscle tension or fatigue), a GAD-7 screening test can help assess the severity of anxiety.4 Similarly, for patients exhibiting intrusive thoughts and compulsive behaviors, the Yale-Brown Obsessive-Compulsive Scale can be used to screen for obsessive-compulsive disorder.5 If there are concerns about substance use, screening tools (eg, the Alcohol Use Disorders Identification Test or Drug Abuse Screening Test) are effective in identifying SUDs.6,7 These screening tools identify mental health issues and can guide further evaluation, diagnosis, and treatment (Table 1).2

For patients who present with mild-to-moderate symptoms of depression or anxiety, PCPs can, and do, initiate management. Evidence-based approaches (eg, psychotherapy such as cognitive-behavioral therapy [CBT]) or medication (such as SSRIs or serotonin-norepinephrine reuptake inhibitors) often manage symptoms effectively. For example, if depression has developed, initial treatment might include prescription of an antidepressant or advising about lifestyle changes (including exercise, dietary modifications, and improvements in sleep hygiene), which can enhance mood. For anxiety, patients can embark upon CBT and relaxation techniques, while simultaneously considering medications like SSRIs if needed.

In cases of more intense, persistent, or worsening symptoms, specialized mental health care (eg, referring the patient to a psychologist for psychotherapy, to a psychiatrist for medication management, or to another type of mental health provider) is often critical (Table 1). In addition, patients with treatment-resistant depression, bipolar disorder, schizophrenia, and personality disorders often require care that is outside of the comfort zone of many PCPs.

Referral to a psychiatrist is appropriate when a patient’s evaluation and mental health issues lie beyond the scope of primary care practices (eg, when depression or anxiety is persistent or severe; when the ability to function at work, school, or in relationships is markedly impaired; when the patient is at risk of suicide). If these issues have failed to respond to initial treatments (eg, counseling, psychotherapy, or use of medication), referral for more advanced care (eg, for schizophrenia, bipolar disorder, or a personality disorder) is advised. Mental health professionals often play a crucial role in the management of psychotropic medications, with monitoring for adverse effects and drug interactions.

Referral to an emergency department (ED) is necessary when a patient’s psychiatric or medical condition poses an imminent threat to their safety (eg, manifest by thoughts of suicide, self-injurious behaviors) or the safety of others.8 Similarly, if new-onset psychosis arises (eg, with hallucinations, delusions, or disorganized thinking) and function is impaired, care in the ED may be required for assessment and stabilization. Lastly, any psychiatric or medical condition that presents with acute, life-threatening signs and symptoms (eg, an altered mental status due to a medical condition or intoxication, delirium tremens, seizures) requires immediate ED care.

What Types of Mental Health Professionals Collaborate With PCPs and What Treatment Can They Provide?

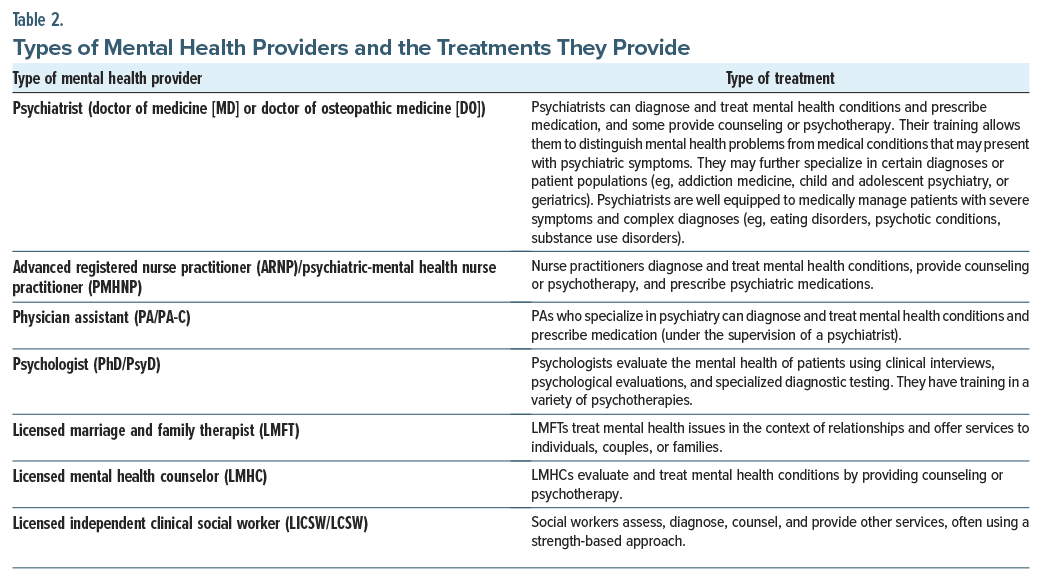

Mental health providers (eg, in nursing, psychology, psychiatry, social work) undergo different types of training (eg, in the practice of psychotherapy, counseling, psychopharmacology) to appreciate the complex interplay among medical conditions, medications, psychological reactions, and social service. Table 2 describes the different types of mental health providers and the treatments they may provide.1

What Types of Talking Therapies Can Mitigate Symptoms and Enhance Function?

Myriad types of psychotherapy are available to improve how patients feel and function. Table 3 describes the types of therapy provided by mental health professionals.

Can Mental Health Care Be Delivered Virtually?

Telehealth is a viable treatment strategy that allows practitioners to provide psychiatric evaluations, psychotherapy, medication management, and patient education remotely (ie, virtually). Moreover, telepsychiatry reduces patient-incurred costs and travel time to appointments, improves accessibility of services, and produces treatment outcomes that are comparable to in-person care.11 Unfortunately, not everyone has access to high-speed internet connections, virtual interpreter services, and a private space to hold telehealth visits.12 Thus, before conducting a telehealth session, PCPs should assess their patient’s readiness to engage with virtual care, and they should obtain informed consent13–15 and realize that complex diagnostic evaluations often require providers to assess nonverbal cues, body language, and elements of the mental status examination that can be made more reliably in person.

PCPs should also know their patient’s contact information, support system, medical status, and how far they are from the nearest emergency medical facility. For example, if medical aspects of a patient’s care are relevant (eg, side effects associated with psychotropic management or dysregulation of physiologic parameters), an in-person examination may need to be arranged.13 While obtaining the informed consent, PCPs should also discuss when it will no longer be safe to manage the patient virtually. During this process, PCPs should establish a plan on how to connect with locally available emergency services, which may include in-person emergency medical or psychiatric services at the patient’s location.14 Compliance with specific local, state, and federal regulations around the prescription of controlled substances may also necessitate an in-person evaluation.13 Those most likely to benefit from virtual mental health visits include individuals who are providing care for young children or the elderly, those who are immunocompromised, or those who struggle with busy schedules, medical challenges, or social determinants of care that preclude easy transportation for care.15

What Is Integrated Care?

Integrated care combines many models, including collaborative care, colocated care, care management, health psychology, consultation-liaison psychiatry, and enhanced referral.16 A growing body of research has demonstrated the efficacy (ie, improving health outcomes) of integrating behavioral/mental health care with primary care. Operationalization of integrated care can face resistance from providers concerned with a perceived loss of autonomy and enduring beliefs about the definition of “good” treatment. The frequent use of standardized assessment instruments in integrated care contrasts with the long-held belief that open-ended questions yield the most reliable information. Outcome studies to date demonstrate that integrated care approaches equal or exceed specialized mental health care in terms of measures of functional and symptomatic relief and patient satisfaction.16

What Is Collaborative Care?

Collaborative care is an evidence-based care delivery model developed by Katon and colleagues17 at the University of Washington that systematically integrates behavioral health case managers and psychiatric consultants into primary care to treat mental health conditions. The model was designed to provide psychiatric care in primary care settings, and it has been adapted for care in a variety of medical specialty clinics. Core members of the team include a primary care provider, a behavioral health care manager, and a consulting psychiatrist.18 Behavioral health care managers are embedded in primary care clinics and play various roles. They participate in making a diagnosis and planning treatment, coordinating treatment, providing proactive follow-up to assess treatment response, supporting medication management, facilitating communication among team members, and offering brief psychotherapies. The psychiatrist on the team provides indirect consultation (informal or “curbside”) to increase access to psychiatric expertise, develops the capacity of PCPs (through training about treatment of common mental health conditions) through education and modeling, provides immediate recommendations to primary care and behavioral health specialists regarding diagnosis and management, provides direct consultation to patients who are not improving, and reviews cases within the patient registry to intensify or “step-up” care when patients fail to respond to current treatments. By reducing the stigma and logistical barriers that deter patients from seeking mental health care, collaborative care successfully enhances access to mental health care. In addition, collaborative care incorporates population health principles, focusing on assessment and improvement of care across an entire panel of patients, and thus achieves more efficient mental health care at a lower cost.

Unfortunately, alleviation of mental health conditions (eg, depression) does not always reduce medical morbidity. For example, a systematic review and meta-analysis of collaborative care for comorbid depression and diabetes showed that a reduction of depressive symptoms did not reliably improve self-care and glycemic control (when depression treatment did not target adherence to diabetes treatment).19 However, quality improvement strategies for diabetes care that promote glucose self-monitoring among patients were found to significantly improve the hemoglobin A1c (HbA1c) level (eg, the standard mean difference was 0.57% [0.31% to 0.83%]).20 Evidence from a sensitivity analysis19 showed that the effect of collaborative care on HbA1c was almost entirely confined to 3 studies that integrated diabetes care within the collaborative care model.21–23

What Is the Evidence for the Efficacy of Collaborative Care?

The evidence for the effectiveness of collaborative care across a variety of outcomes is robust. Research suggests that for a range of conditions, including depression and anxiety, collaborative care significantly improves mental health outcomes compared to usual care.24 A systematic review and meta analysis25 suggested that collaborative care improves behavioral health outcomes, medication adherence, and patient satisfaction. Collaborative care leads to better outcomes (ie, better screening, adherence to care), reduced health care utilization, and a reduced financial burden over time.26 Across studies, collaborative care has been effective, cost-effective, and scalable.

How Can Collaborative Care Be Delivered?

Collaborative care can be delivered through either colocated (ie, on-site) or virtual (ie, off-site, technology-facilitated) configurations. Both models share a team-based approach but differ in their practical considerations. Colocated collaborative care involves the physical presence of behavioral health specialists within primary care settings. Physically embedded care has distinct advantages, including more seamless access to medical records as well as quicker response times to emerging clinical situations.

The Veterans Health Administration (VHA) has the largest integrated health care system in the United States, serving over 9 million enrolled veterans each year. Primary care mental health integration services at Veterans Affairs (VA) medical centers and community-based outpatient clinics were designed based on the “White River Model of Co-located Collaborative Care: A Platform for Mental and Behavioral Health Care in the Medical Home,” which was first implemented in 2004.27 The primary mental health care clinic at the White River Junction Veterans Affairs Medical Center, Vermont, is staffed by a therapist and a psychiatrist (or advanced practice nurse), complemented by care management and health psychology, and it offers a full spectrum of mental health care. This model has allowed 75% of referred patients to receive all of their care within the appropriately resourced primary care clinic, thereby conserving specialty mental health care services for the most complex patients.27 Integration of mental health care into primary care and medical settings offers improved quality of care for patients with chronic medical illnesses (eg, diabetes) who frequently suffer from psychiatric comorbidities (eg, depression).

Another paradigm, the “mental health home” model (also called the “behavioral health home”), places great importance on enhancing the interface of psychiatry with PCPs and social services to support individuals suffering from severe mental illness (eg, schizophrenia).28 This model aims to help individuals improve quality of life and well-being via active monitoring of basic health indicators (eg, smoking status, body mass index, blood pressure) and lifestyle choices (eg, physical activity, nutrition) for patients with severe mental illness.

Teleconsultation can be used to connect off-site mental health professionals with primary care teams via telephone and video calls. Evidence suggests that virtual-based collaborative care can achieve equal or better outcomes than colocated care, potentially because teleconsultation (versus colocated) facilitates higher fidelity to evidence-based collaborative care protocols. This has been established in rural clinical settings that have more limited access to mental health providers.29 Nonetheless, teleconsultation has its limitations. Off-site providers, particularly outside of the care system, may have more challenges accessing medical records, and there may be greater delays in clinical responses.

Overall, colocated and teleconsultation collaborative care models are both promising options. The strengths of colocated care include greater responsivity to clinical situations and potentially fewer barriers to medical records, whereas the strengths of teleconsultation include bringing specialization to clinical settings where mental health resources might be more limited as well as potentially higher fidelity to empirically supported care models.

How Does Collaborative Care in Private Practice Differ From Such Care in Academic Medicine?

Collaborative care in private practice and academic medicine shares the same foundational principles of team-based care with the aim of integrating behavioral health into general medical settings. However, their mission differs. In private practice, the implementation of collaborative care can occasionally be constrained by a smaller number of clinicians as well as by reimbursement and resource challenges. Private practices, given that they tend to be smaller, may lack the administrative support and protected administrative time that can facilitate the implementation of collaborative care models. That said, motivated practitioners who are committed to the mission of collaborative care can overcome these obstacles.

In contrast to private practice, academic medicine may have an easier time implementing collaborative care models. Academic medical centers may have more resources dedicated to embedding behavioral health providers and care managers, as well as the resources for supporting billing personnel. In addition, academic medical centers are often more familiar with the integration of measurement-based care and quality improvement processes into clinical practice. Some barriers to adoption in academic medicine include hierarchical decision-making and slower adoption of newer workflows, given greater bureaucratic constraints.

Both private practice and academic medicine are settings in which collaborative care can thrive. Academic medicine often has structures that facilitate adoption of collaborative care models, although its hierarchical structure may slow implementation. Private practice may have challenges around resources given their relatively smaller size, but they can be nimbler, facilitating use of more novel care delivery models.

How Has the Reimbursement for and the Availability of Mental Health Care Changed?

Treatment of mental illness is costly (ie, over $280 billion annually in the United States),30 and the cost for mental health care treatment varies significantly, depending on the location, type of treatment, and one’s insurance coverage. Broadly speaking, there are insurance-covered interventions, out-of-network interventions, and out-of-pocket payments. Insurance coverage varies widely, from employer-sponsored health insurances to Medicaid and Medicare to marketplace insurances for inpatient, partial, residential, and outpatient services.

When using a provider who is in-network for an insurance plan, individuals often pay a copay after their deductible has been reached (with significant variation across insurance plans). In addition, employee assistance plans often offer a limited number of free therapy sessions, and community mental health centers often provide treatment at a significant cost reduction. Patients can call their insurance carriers for more specific information related to their plans.

Out-of-network psychiatric care is becoming increasingly prevalent, and costs also vary widely. Patients can seek out-of-network reimbursement from their insurance carriers if they have a preferred provider organization (PPO). PPOs typically allow for out-of-network coverage, and there are reduced needs for referrals, which allows for greater flexibility. These plans tend to have higher premiums and deductibles, and they tend to reimburse a percentage of a reasonable and customary fee for a given service (eg, psychotherapy, medication management). Although most out-of-network services are provided to outpatients, some out-of-network services are available for higher levels of care (eg, residential treatment). Costs for outpatient psychotherapy are highly variable, starting around $50 and going up to $500 or more for visits with specialized providers in areas with a higher cost of living. Services for psychopharmacology tend to be more expensive than those for psychotherapy.

How Can Family Members of Your Patients Cope Better?

When patients experience psychiatric distress and medical challenges, family members and couples become stressed. Incorporating family and couples therapy into treatment plans can support patients and their family systems and reduce their stress. Family and couples therapy also mitigates burnout of caregivers and enhances communication and coping strategies in the patient and their family. Thus, engaging your patients’ family members can serve as an important step when treating patients.

Caregiver burden31 often occurs when individuals care for chronically and acutely ill family members. Helping individuals to understand that burnout develops when caring for an ill family member mitigates caregiver burden, thereby reducing stress on the family. Further, couples and family therapy can be efficacious for many conditions, including psychiatric and physical illnesses.32,33

How Can Communication With Mental Health Professionals Be Enhanced?

Several strategies can enhance working relationships and communication among PCPs and mental health professionals. Primary care practices can consider redesigning systems to colocate behavioral health clinicians into their office practice setting or to deploy a collaborative care model.34,35 Both approaches offer an opportunity to schedule real-time consultations and to coordinate treatment. Colocated psychiatric care is distinct from collaborative care in that while PCPs and mental health providers share physical spaces, they may operate without shared workflows. Colocated mental health professionals provide one-on-one assessment and treatment of patients. Collaborative care expands beyond physical proximity to implement the systematic tracking of mental health outcomes and facilitate active communication through a structured team of PCPs, case managers, and psychiatrists who serve as consultants.34

Rapport-building further improves communication. Proactive meetings between primary care and behavioral health facilitate clarity on referral pathways for collaboration and seamless patient care handoffs. For instance, a seminal randomized controlled trial, called Improving Mood-Promoting Access to Collaborative Treatment, examined outcomes with a collaborative care management program for late-life depression and established the foundation for indication for referral to psychiatry. This includes diagnostic uncertainty (eg unipolar depression versus bipolar disorder); severe or treatment-resistant symptoms (eg, continued symptoms despite multiple trials of antidepressants, medication complications); safety concerns (eg suicidal ideation with intent and/or plan); comorbid substance use, trauma, or personality disorder; and need for specialized treatments (eg clozapine, lithium, or interventional psychiatry).24 Establishing a regular schedule for meetings between PCPs and behavioral health practitioners enhances feedback on processes and practices.35 Moreover, optimal use of the electronic health record (EHR) through staff messaging and note-sharing enables PCPs and mental health professionals to share updates and track progress on a patient’s clinical symptoms, treatment, and outcomes.36 When using the EHR in this manner, message volume should be attended to and managed to keep EHR inboxes from becoming overloaded with redundant notifications.37 PCPs can also consider scheduling regular interdisciplinary meetings, case conferences, and training workshops. Interdisciplinary meetings with mental health professionals provide the opportunity to review care of patients with complex problems and to adjust treatment plans and review barriers to care (eg, social determinants of mental health).38 Case conferences or training workshops can focus on specific mental health topics, inspired by specific cases, with a mental health professional providing expert analysis and education on the assessment and treatment of patients.38 Finally, leadership support from both primary care and behavioral health plays a pivotal role in fostering a culture of open dialogue and trust, which prioritizes the experience of patients and providers.

To enhance the behavioral health assessment and evaluation of patients in primary care, valuable resources include the American Psychiatric Association clinical practice guidelines38 and National Institute of Mental Health topics on mental health.39 In addition, useful references include textbooks (eg, Psychiatry Essentials for Primary Care,40 Integrated Care: Working at the Interface of Primary Care and Behavioral Health,41,42 the Massachusetts General Hospital Handbook of General Hospital Psychiatry, Eighth Edition,43 and the Massachusetts General Hospital Guide to Primary Care Psychiatry, Second Edition44). These are practical and popular guides filled with case examples.

Is Informed Consent From Patients (about communication with your colleagues) Necessary When Seeking Consultation or Referral?

Effective collaboration between PCPs and mental health professionals is a cornerstone of integrated care, but it raises important questions about when informed patient consent is required for interprofessional communication. While federal regulations like the Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act (HIPAA) generally allow providers to share protected health information (PHI) for treatment purposes without specific patient authorization, there are some important exceptions that clinicians must understand.

Under HIPAA, treating providers may communicate and exchange information related to diagnosis, treatment, and care coordination without obtaining explicit consent from the patient.45–47 This facilitates routine collaboration between PCPs and mental health professionals. However, certain types of mental health information are subject to stricter rules. For example, psychotherapy notes (defined as a clinician’s private documentation of a counseling session) are not considered standard PHI and cannot be shared without a written authorization from the patient.45,47

SUD treatment records are also governed by additional federal protections under 42 Code of Federal Regulations Part 2. These regulations typically require written consent for disclosure, even between treating providers, unless the situation qualifies as a narrowly defined emergency (to prevent death or serious harm).46–49 While intended to protect patient privacy, these requirements often complicate care coordination and have been identified in the literature as a barrier to integrated behavioral health services.48,49 Some health systems have adopted solutions such as limiting access to sensitive notes within EHRs, but these do not replace the need for formal patient consent.49

State laws may further restrict the sharing of behavioral health information. Some states require explicit consent for telehealth consultations or allow minors to control access to their mental health records.46,50 In any clinical setting, the most protective applicable law, whether federal or state, takes precedence. 46,50

Even when not legally mandated, discussing consent with patients may be consistent with ethical best practices. It supports autonomy, fosters trust, and encourages transparency in the care relationship. Many mental health providers view consent as part of a broader, patient-centered dialogue that can help reduce stigma and clarify the purpose of provider collaboration.45,51,52 For adolescents in particular, professional guidelines recommend involving them in decisions about information sharing to enhance engagement and clinical outcomes.50

In practice, although HIPAA allows treatment-related communication between providers without explicit patient consent, exceptions involving psychotherapy notes, SUD records, and specific state laws require careful attention. Proactively engaging patients in discussions about consent may reflect both legal compliance and respectful care, especially in the context of mental health.

What Happened to Mr C?

Mr C’s PCP increased his clonazepam dose to 1 mg at night and maintained his sertraline and other medications. In addition, Mr C’s PCP referred him to the hospital’s collaborative care program. As part of this program, Mr C and his PCP were connected to a care manager, a consulting psychiatrist, and a licensed clinical social worker.

The care manager reached out to Mr C, and they met twice online. Mr C was offered resources to help navigate unemployment, as well as job search resources. Further, the care manager ensured that Mr C could fill his prescriptions at the pharmacy. The case manager met with Mr C and his wife and educated them about the importance of getting out of bed, increasing socialization, and exercising. The psychiatrist reviewed Mr C’s chart and, in collaboration with his PCP, made several recommendations. Given his marginal response to sertraline and without much room to raise the dose, Mr C’s regimen was cross-titrated to fluoxetine (with a target dosage of 40–60 mg/d, depending on his response). In addition, the psychiatrist recommended starting trazodone 50 mg at night for insomnia. Finally, recommendations were given to the PCP regarding an eventual taper and discontinuation of clonazepam, given Mr C’s family history of substance use and his recent need for higher doses.

In addition to working with a care manager and a consulting psychiatrist, Mr C was connected to a social worker. The social worker met weekly with the patient via telehealth for 50 minutes, and the empirically backed unified protocol32 was administered. The unified protocol has been effective as a transdiagnostic treatment for anxiety and depression. In this psychotherapy, Mr C learned ways to deal with his unhelpful cognitions, mindfulness strategies, and the importance of engaging in health-promoting behaviors (eg, exercise and socialization to improve mood).

Within 1 month, Mr C’s thoughts of suicide abated, and after 6 weeks, his mood and anxiety improved. At 8 weeks, Mr C’s sleep had returned to normal (sleeping 7 hours per night), and his feelings of guilt and sadness substantially diminished. His wife supported the patient by encouraging him to exercise and attend his psychotherapy sessions. His PCP continued to prescribe his psychiatric medications (60 mg/d of fluoxetine, 50 mg/d of trazodone) and successfully tapered and discontinued clonazepam. Mr C worked with his therapist to learn skills to improve his mood and prevent relapse.

CONCLUSION

Mental health care often involves the delivery of psychotherapy and psychopharmacology by a range of mental health providers. Referral to a psychiatrist is appropriate when a patient’s problems lie beyond the scope of primary care practice (eg, when patients experience persistent and severe symptoms of depression, anxiety, or other psychiatric conditions that significantly impair their ability to function in daily life, eg, in work, school, or relationships). Virtual mental health care allows practitioners to provide psychiatric evaluation, therapy, medication management, and patient education remotely. Telepsychiatry reduces patient-incurred costs and travel time to appointments, improves accessibility of services, and produces treatment outcomes that are comparable to in-person care.

Collaborative care is an evidence-based care delivery model that systematically integrates behavioral health case managers and psychiatric consultants into primary care to treat mental health conditions. It incorporates population health principles and focuses on the assessment and improvement of care across an entire panel of patients and thus achieves more efficient mental health care at a lower cost.

Article Information

Published Online: November 13, 2025. https://doi.org/10.4088/PCC.25f03977

© 2025 Physicians Postgraduate Press, Inc.

Submitted: March 28, 2025; accepted August 8, 2025.

To Cite: Cohen JN, Lee JH, Nadkarni A, et al. Collaboration between primary care providers and mental health professionals: rationale and clinical practice. Prim Care Companion CNS Disord 2025;27(6):25f03977.

Author Affiliations: Department of Psychiatry, Harvard Medical School, Boston, Massachusetts (Cohen, Lee, Nadkarni, Stern); Massachusetts General Hospital, Boston, Massachusetts (Cohen, Stern); Brigham and Women’s Faulkner Hospital, Mass General Brigham, Boston, Massachusetts (Lee); Department of Psychiatry, Mass General Brigham Academic Medical Centers, Boston, Massachusetts (Nadkarni); Geisel School of Medicine at Dartmouth, Lebanon, New Hampshire (Rustad); Larner College of Medicine at University of Vermont, Burlington, Vermont (Rustad); White River Junction VA Medical Center, White River Junction, Vermont (Rustad); Burlington Lakeside Community Based Outpatient Clinic, Burlington, Vermont (Rustad).

Corresponding Author: Jonah N. Cohen, PhD, Department of Psychiatry, Massachusetts General Hospital, 1 Bowdoin Square, 6th Floor, Boston, MA 02114 ([email protected]). Cohen, Lee, Nadkarni, and Rustad are co-first authors; Stern is senior author.

Relevant Financial Relationships: Dr Rustad is employed by the United States Department of Veterans Affairs, but the opinions expressed in this article do not reflect those of the Department of Veterans Affairs. Dr Stern has received royalties from Elsevier for editing textbooks on psychiatry. The other authors report no relevant financial relationships.

Funding/Support: None.

Clinical Points

- Since primary care physicians (PCPs) are often the first health care professionals to see patients with symptoms of a mental health disorder, they play a vital role in the identification, management, and referral of psychiatric conditions (eg, depression, anxiety, substance use disorders, and psychosis).

- Referral to an emergency department is necessary when a patient’s acute psychiatric or medical condition poses an imminent threat to their safety (eg, due to having thoughts of suicide or their engaging in self-harming behaviors) or the safety of others.

- Several brands of psychotherapy can be initiated (eg, cognitive-behavioral therapy that targets depressed patients’ irrational beliefs and distorted cognitions that perpetuate depressive symptoms by challenging and reversing them, and dialectical behavior therapy teaches skills to help control impulsive and harmful behaviors).

- PCPs should be proactive and meet with their mental health colleagues to discuss their mutual interests in improving integrated care for shared patients and to facilitate collaboration and seamless patient care handoffs.

References (52)

- University of Washington Psychiatry and Behavioral Sciences. Types of mental health providers. 2022. https://psychiatry.uw.edu/wp-content/uploads/2022/05/Types-of-MH-providers.pdf

- Salinas A, Crenshaw JT, Gilder RE, et al. Implementing the evidence: routine screening for depression and anxiety in primary care. J Am Coll Health. 2024;72(8):2893–2898. PubMed CrossRef

- Kroenke K, Spitzer RL, Williams JB. The PHQ-9: validity of a brief depression severity measure. J Gen Intern Med. 2001;16(9):606–613. PubMed CrossRef

- Spitzer RL, Kroenke K, Williams JBW, et al. A brief measure for assessing generalized anxiety disorder: the GAD-7. Arch Intern Med. 2006;166(10):1092–1097. PubMed CrossRef

- Goodman WK, Price LH, Rasmussen SA, et al. The Yale-Brown Obsessive Compulsive Scale. I. Development, use, and reliability. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1989;46(11):1006–1011. PubMed CrossRef

- Saunders JB, Aasland OG, Babor TF, et al. Development of the Alcohol Use Disorders Identification Test (AUDIT): WHO collaborative project on early detection of persons with harmful alcohol consumption-II. Addiction. 1993;88(6):791–804. PubMed CrossRef

- Yudko E, Lozhkina O, Fouts A. A comprehensive review of the psychometric properties of the Drug Abuse Screening Test. J Subst Abuse Treat. 2007;32(2):189–198. PubMed CrossRef

- da Silva AG, Baldaçara L, Cavalcante DA, et al. The impact of mental illness stigma on psychiatric emergencies. Front Psychiatry. 2020;11:573. PubMed CrossRef

- Karrouri R, Hammani Z, Benjelloun R, et al. Major depressive disorder: validated treatments and future challenges. World J Clin Cases. 2021;9(31):9350–9367. PubMed CrossRef

- U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs. Learn about treatment. 2025. https://www.mentalhealth.va.gov/get-help/treatment/ebt.asp

- Bulkes NZ, Davis K, Kay B, et al. Comparing efficacy of telehealth to in-person mental health care in intensive-treatment-seeking adults. J Psychiatr Res. 2022;145:347–352. PubMed CrossRef

- Telehealth for the Treatment of Serious Mental Illness and Substance Use Disorders. SAMHSA, 2021. Accessed March 20, 2025. https://library.samhsa.gov/sites/default/files/pep21-06-02-001.pdf

- Best Practices in Videoconferencing-Based Telemental Health. American Psychiatric Association, 2018. Accessed March 20, 2025. https://www.psychiatry.org/getmedia/05b9b9cb-dbb5-4df8-8948-e2b9bd659b55/APA-ATA-Best-Practices-in-Videoconferencing-Based-Telemental-Health.pdf

- APA Guidelines for the Practice of Telepsychology, 2024. Accessed March 20, 2025. https://www.apa.org/practice/guidelines/telepsychology-revision.pdf

- Palmer CS, Brown Levey SM, Kostiuk M, et al. Virtual care for behavioral health conditions. Prim Care. 2022;49(4):641–657. PubMed CrossRef

- Pomerantz AS, Corson JA, Detzer MJ. The challenge of integrated care for mental health: leaving the 50-minute hour and other sacred things. J Clin Psychol Med Settings. 2009;16(1):40–46. PubMed CrossRef

- Katon W, Von Korff M, Lin E, et al. Collaborative management to achieve treatment guidelines: impact on depression in primary care. JAMA. 1995;273(13):1026–1031. PubMed

- Raney L. Integrating primary care and behavioral health: the role of the psychiatrist in the collaborative care model. Am J Psychiatry. 2015;172(8):721–728. PubMed CrossRef

- Atlantis E, Fahey P, Foster J. Collaborative care for comorbid depression and diabetes: a systematic review and meta-analysis. BMJ Open. 2014;4(4):e004706. PubMed CrossRef

- Tricco AC, Ivers NM, Grimshaw JM, et al. Effectiveness of quality improvement strategies on the management of diabetes: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet. 2012;379(9833):2252–2261. PubMed CrossRef

- Bogner HR, de Vries HF. Integrating type 2 diabetes mellitus and depression treatment among African Americans: a randomized controlled pilot trial. Diabetes Educ. 2010;36:284–292. PubMed CrossRef

- Bogner HR, Morales KH, de Vries HF, et al. Integrated management of type 2 diabetes mellitus and depression treatment to improve medication adherence: a randomized controlled trial. Ann Fam Med. 2012;10(1):15–22. PubMed CrossRef

- Katon WJ, Lin EHB, Von Korff M, et al. Collaborative care for patients with depression and chronic illnesses. N Engl J Med. 2010;363(27):2611–2620. PubMed CrossRef

- Unützer J, Katon W, Callahan CM, et al. Collaborative care management of late-life depression in the primary care setting: a randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 2002;288(22):2836–2845. PubMed

- Archer J, Bower P, Gilbody S, et al. Collaborative care for depression and anxiety problems. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2012;10:CD006525. PubMed CrossRef

- Reiss-Brennan B, Brunisholz KD, Dredge C, et al. Association of integrated team-based care with health care quality, utilization, and cost. JAMA. 2016;316(8):826–834. PubMed CrossRef

- Pomerantz AS, Shiner B, Watts BV, et al. The White River model of colocated collaborative care: a platform for mental and behavioral health care in the medical home. Fam Syst Health. 2010;28(2):114–129. PubMed CrossRef

- Smith TE, Sederer LI. A new kind of homelessness for individuals with serious mental illness? The need for a “Mental Health Home.” Psychiatr Serv. 2009;60(4):528–533. PubMed CrossRef

- Fortney JC, Pyne JM, Mouden SB, et al. Practice-based versus telemedicine-based collaborative care for depression in rural federally qualified health centers: a pragmatic randomized comparative effectiveness trial. Am J Psychiatry. 2013;170(4):414–425. PubMed CrossRef

- Abramson B, Boerma J, Tsyvinski A. Macroeconomics of Mental Health (No. w32354). National Bureau of Economic Research;2024.

- Adelman RD, Tmanova LL, Delgado D, et al. Caregiver burden: a clinical review. JAMA. 2014;311(10):1052–1060. PubMed CrossRef

- Cottrell D, Boston P. Practitioner review: the effectiveness of systemic family therapy for children and adolescents. J Child Psychol Psychiatry. 2002;43(5):573–586. PubMed CrossRef

- Pinsof WM, Wynne LC. The efficacy of marital and family therapy: an empirical overview, conclusions, and recommendations. J Marital Fam Ther. 1995;21(4):585–613. CrossRef

- Reist C, Petiwala I, Latimer J, et al. Collaborative mental health care: a narrative review. Medicine. 2022;101(52):e32554. PubMed CrossRef

- Kates N, Arroll B, Currie E, et al. Improving collaboration between primary care and mental health services. World J Biol Psychiatry. 2019;20(10):748–765. PubMed CrossRef

- McGregor B, Mack D, Wrenn G, et al. Improving service coordination and reducing mental health disparities through adoption of electronic health records. Psychiatr Serv. 2015;66(9):985–987. PubMed CrossRef

- Yeager VA, Taylor HL, Menachemi N, et al. Primary care case conferences to mitigate social determinants of health: a case study from one FQHC system. Am J Accountable Care. 2021;9(4):12–19. PubMed CrossRef

- American Psychiatric Association. APA Clinical Practice Guidelines. Accessed August 4, 2025. https://www.psychiatry.org/psychiatrists/practice/clinical-practice-guidelines

- National Institute of Mental Health (NIMH) topics on mental health. Accessed August 4, 2025. https://www.nimh.nih.gov/health/topics

- Schneider RK, Levenson JL. Psychiatry Essentials for Primary Care. ACP Press;2008.

- Raney LE, ed. Integrated Care: Working at the interface of Primary Care and Behavioral Health. American Psychiatric Pub;2015.

- Advancing Integrated Mental Health Solutions (AIMS) Center at University of Washington. Collaborative Care Implementation Guide. https://aims.uw.edu/resource/collaborative-care-implementation-guide/

- Stern TA, Beach SR, Smith FA, et al, eds. Massachusetts General Hospital Handbook of General Hospital Psychiatry. Eighth Edition. Elsevier;2025.

- Stern TA, Herman JB, Slavin PL, eds. Massachusetts General Hospital Guide to Primary Care Psychiatry. 2nd ed. McGraw-Hill; 2004.

- Appelbaum PS. Privacy in psychiatric treatment: threats and responses. Am J Psychiatry. 2002;159(11):1809–1818. PubMed CrossRef

- Pessar SC, Boustead A, Ge Y, et al. Assessment of state and federal health policies for opioid use disorder treatment during the COVID-19 pandemic and beyond. JAMA Health Forum. 2021;2(11):e213833. PubMed CrossRef

- Mishkind M, Boyce O, Krupinski E, et al. Best Practices in Synchronous Videoconferencing-Based Telemental Health. American Psychiatric Association; 2022. Accessed July 30, 2025. https://www.americantelemed.org/wp-content/uploads/2022/05/Best-Practices-in-Synchronous-Videoconferencing-Based-Telemental-Health-March-2022.pdf

- McCarty D, Rieckmann T, Baker RL, et al. The perceived impact of 42 CFR Part 2 on coordination and integration of care: a qualitative analysis. Psychiatr Serv. 2017;68(3):245–249. PubMed CrossRef

- Campbell ANC, McCarty D, Rieckmann T, et al. Interpretation and integration of the federal substance use privacy protection rule in integrated health systems: a qualitative analysis. J Subst Abuse Treat. 2019;97:41–46. PubMed CrossRef

- Chung RJ, Lee JB, Hackell JM, et al. Confidentiality in the care of adolescents: Policy statement. Pediatrics. 2024;153(5):e2024066326. PubMed CrossRef

- Leung E, Graziano M, Coleman M, et al. Behavioral health providers’ perspectives on supporting patient decisions in sharing treatment information in substance use and mental health settings: a qualitative study. Patient Educ Couns. 2025;137:108829. PubMed CrossRef

- Fisher CB, Oransky M. Informed consent to psychotherapy: protecting the dignity and respecting the autonomy of patients. J Clin Psychol. 2008;64(5):576–588. PubMed CrossRef

Enjoy this premium PDF as part of your membership benefits!