Adenosine monophosphate (AMP) is vital for cellular energy and physiologic functions.1 While used in veterinary medicine for muscle recovery,1 its human use is largely unexplored, leading to concerning unsupervised misuse.2 A trend of individuals seeking unregulated substances for perceived benefits has resulted in the misuse of readily available veterinary AMP.2 This includes equine medications increasingly used for performance enhancement,3 highlighting a hazardous pattern of nontraditional substance abuse. This report details a rare case of severe intravenous veterinary AMP dependence,2 offering crucial insights into public health risks from drug diversion2 and underscoring a critical gap in human AMP dependence research.2

Case Report

A 41-year-old man presented to our clinic with a 6-month history of severe anxiety, intermittent paranoia, distressing ideas of infidelity, profound exhaustion, low mood, loss of interest in previously enjoyed activities, and disrupted sleep. Physical examination revealed multiple needle marks on his arms. Initial considered diagnoses included primary anxiety disorder, major depressive disorder, and possible delusional disorder. Symptomatic treatment was initiated, including risperidone (titrated up to 3 mg daily for paranoia and agitation), escitalopram (up to 15 mg daily for mood and anxiety), clonazepam (up to 1 mg daily for restlessness), zolpidem (up to 10 mg daily for sleep), and propranolol (20 mg daily for palpitations and tremors).

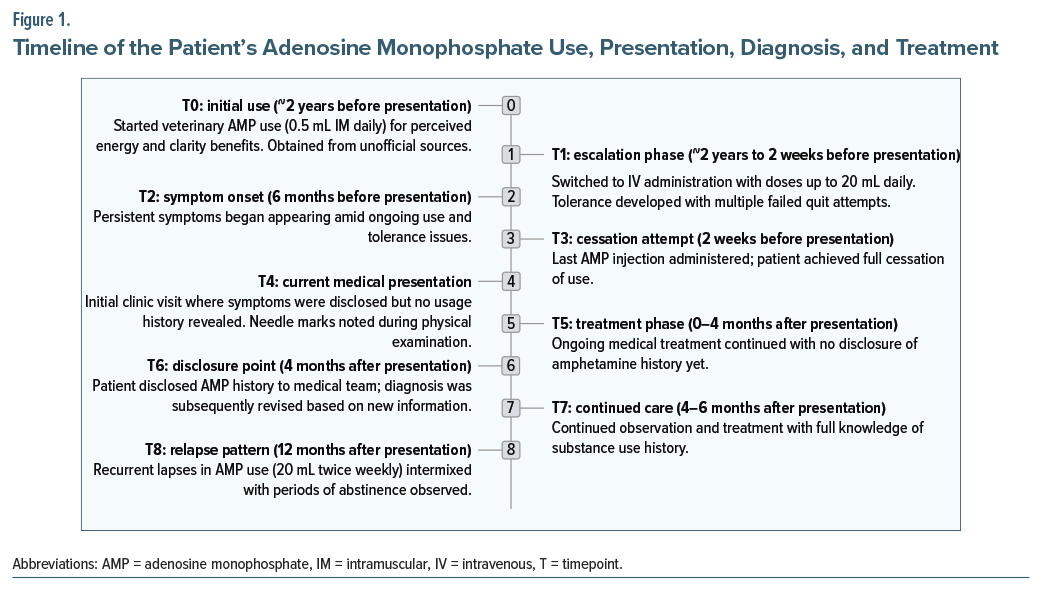

Over the first 4 months of regular follow-up, symptoms fluctuated with brief periods of relief but no overall improvement, despite medication adjustments. This lack of response prompted further inquiry. At the 4-month visit, the patient disclosed a 2-year history of self-administering veterinary-grade AMP, obtained through unofficial sources, believing it enhanced physical vitality and mental clarity. Use began ∼2 years prior with 0.5-mL intramuscular injections daily. Within months, he escalated to intravenous administration, reaching 10 mL per dose, and eventually 20 mL per dose 4–5 times daily—far exceeding any guidelines.1 Postinjection effects included temporary energy, focus, and reduced fatigue, but tolerance developed, requiring higher doses. Failed cessation attempts caused intense restlessness, palpitations, tremors, paranoid ideas, and lethargy. His last injection was 2 weeks before presentation, after which withdrawal symptoms intensified, manifesting as the presenting complaints that had persisted for 6 months.

Based on this history and the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fifth Edition, criteria,4 the diagnosis was revised to stimulant use disorder (AMP dependence). The ongoing symptoms were reinterpreted as withdrawal related, with no evidence of other substance use. Medications were continued and targeted toward withdrawal management over the subsequent 2 months (total 6-month observation period postpresentation). No major changes in regimen occurred, but doses were titrated as needed for symptom control. While specific responses to individual adjustments are not detailed here, the patient achieved symptomatic stability without relapse, suggesting gradual improvement in withdrawal effects (eg, reduced autonomic symptoms with propranolol and better mood/sleep with escitalopram/zolpidem).

At 12 months postpresentation, the patient reported recurrent lapses in AMP use (20 mL 2 or 3 times/week), intermixed with associated periods of loss of energy. However, other symptoms (anxiety, low mood, infidelity ideas) have not recurred with continued medications. This indicates partial long-term response, with ongoing risk of relapse. Further follow-up is ongoing to monitor recovery. Figure 1 provides a timeline of the patient’s AMP use, presentation, diagnosis, and treatment.

Discussion

This report details a case of severe human dependence on high-dose intravenous veterinary AMP, demonstrating a pattern consistent with established substance use disorders through rapid dose escalation, tolerance, cravings, and severe withdrawal. The stimulant effects and dependence potential of AMP likely stem from its involvement in adenosine and dopamine neurotransmission.1 Adenosine’s complex influence on the central nervous system5 may explain the patient’s reported energy surges, enhanced focus, and severe withdrawal symptoms, including anxiety and paranoia. Further research is warranted to explore how the adenosine system’s interaction with the dopaminergic reward pathway contributes to this dependence.5

Prolonged, high-dose intravenous AMP use leads to significant clinical consequences, such as severe psychological dependence, debilitating withdrawal, and neuropsychiatric complications. The withdrawal symptoms often necessitate sedative treatment, underscoring the complexity of managing such cases. The readily available veterinary AMP, despite being labeled “not for human use,”2 poses a major public health concern.

This case highlights the dangers of unregulated access, particularly for individuals seeking cognitive or physical enhancement,3 revealing a critical regulatory gap. Increased clinician awareness and stronger regulatory measures are essential to effectively curb this nontraditional form of substance abuse.

Article Information

Published Online: January 27, 2026. https://doi.org/10.4088/PCC.25cr04046

© 2026 Physicians Postgraduate Press, Inc. Prim Care Companion CNS Disord 2026;28(1):25cr04046

Submitted: July 20, 2025; accepted October 2, 2025.

To Cite: Garg S, Jawandha A, Mishra P, et al. A unique case of dependence on high-dose veterinary adenosine monophosphate administered intravenously. Prim Care Companion CNS Disord 2026;28(1):25cr04046.

Author Affiliations: Department of Psychiatry, Shri Guru Ram Rai Institute of Medical and Health Sciences, Dehradun, Uttarakhand, India (Garg, Mishra); Neurocare Centre, Uttarakhand, India (Jawandha); Department of Psychiatry, Hi-Tech Medical College, Bhubaneswar, India (Pattojoshi).

Corresponding Author: Shobit Garg, MD, DPM, Department of Psychiatry, Shri Guru Ram Rai Institute of Medical and Health Sciences, Shri Guru Ram Rai University, Dehradun, Uttarakhand, 248001, India ([email protected]).

Financial Disclosure: None.

Funding/Support: None.

Patient Consent: Consent was obtained from the patient to publish the case report, and information has been de-identified to protect patient anonymity.

Use of AI-Assisted Technologies in the Writing Process: The authors acknowledge the use of Gemini Flash (via Google AI Studio) to assist in refining the language. The prompts used focused on improving sentence structure and identifying potential grammatical errors. The authors carefully reviewed and edited the AI-generated suggestions to ensure the final content accurately reflects the intended statement.

ORCID: Shobit Garg: https://orcid.org/0000-0001-5913-9021

References (5)

- Krishan S, Richardson DR, Sahni S. Adenosine monophosphate-activated kinase and its key role in catabolism: structure, regulation, biological activity, and pharmacological activation. Mol Pharmacol. 2015;87(3):363–377. PubMed CrossRef

- Smith ME, Farah MJ. Are prescription stimulants “smart pills”? The epidemiology and cognitive neuroscience of prescription stimulant use by normal healthy individuals. Psychol Bull. 2011;137(5):717–741. PubMed CrossRef

- India Today. Delhi youths taking horse drug to chisel gym-toned bodies quickly. 2019. Accessed May 29, 2025. https://www.indiatoday.in/mail-today/story/delhi-youths-taking-horsedrug-to-chisel-gym-toned-bodies-quickly-1428402-2019-01-11 PubMed

- American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders. 5th ed. American Psychiatric Publishing; 2013. PubMed CrossRef

- Dunwiddie TV, Masino SA. The role and regulation of adenosine in the central nervous system. Annu Rev Neurosci. 2001;24:31–55. PubMed CrossRef

Enjoy this premium PDF as part of your membership benefits!