Huntington disease (HD) is a monogenic autosomal dominant disorder caused by the accumulation of CAG (cytosine-adenine-guanine) repeats in the Huntingtin gene.1,2 Patients with the HD phenotype typically have CAG repeats in the range of 36–55, with the genetic phenomenon of anticipation leading to longer trinucleotide repeats and onset at a younger age in subsequent generations due to the instability of CAG repeats in spermatogenesis.1,2 The pathophysiology of HD is neurodegenerative and specifically thought to be concentrated in the caudate and putamen, although inclusions of the mutant Huntingtin protein are found throughout the brain.1 The clinical diagnosis of HD is most often established based on the presence of positive family history and the manifestation of chorea, which is usually comorbid with other movement abnormalities (dystonia, bradykinesia) and behavioral or psychiatric components.1,3–5 Some of the earlier behavioral symptoms seen in HD can include impulsivity, irritability, and outbursts, which can sometimes be mistaken for a primary psychiatric diagnosis before the diagnosis of HD is made.1,6

Tardive dyskinesia (TD) is a drug-induced movement disorder seen with long-term use of dopamine receptor–blocking agents.7,8 The phenotype of TD is rather broad, with movement that can include chorea, athetosis, dystonic movements, tic-like features, buccolingual stereotypy, and other abnormal movements.7,8 TD is further defined as a movement disorder that persists despite discontinuation of the causative medications for at least 1 month after.7 It is thought to occur due to upregulation and hypersensitivity of dopamine receptors in response to long-term inhibition.7,9

Case Report

A 59-year-old woman presented to the emergency department for new wandering behavior, abnormal movements, weight loss, and medication titration for her psychiatric conditions. Her medical history per chart review was significant for systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE), syphilis, severe protein-calorie malnutrition, bipolar disorder vs schizoaffective disorder of bipolar type, type 2 diabetes mellitus, and hyperlipidemia. Of note, the patient was previously treated with olanzapine 10 mg for 8 years and had subsequently been diagnosed with TD 3 years prior to presentation and prescribed valbenazine 60 mg. Medications at admission included atorvastatin 20 mg/d, bupropion 150 mg/d, cetirizine 10 mg/d, cyanocobalamin 1,000 mcg/d, fluoxetine 20 mg/d, quetiapine 200 mg at bedtime, trazodone 50 mg at bedtime, and valbenazine 60 mg/d.

Per the patient’s group home, there had been increasing concern regarding recent new-onset weight loss and worsening abnormal movements resulting in more frequent falls beginning 8 months ago. She was switched from olanzapine to quetiapine by her outpatient psychiatrist due to concern regarding worsening TD symptoms 3 months prior. While the diagnoses of syphilis and SLE were present in the chart, it was unclear what testing was used to make the diagnoses and which treatments the patient had been provided with in the past. Initial investigations showed that vital signs, complete blood count and comprehensive metabolic panels, and thyroid studies were within normal limits.

Diagnosis. The differential for the patient’s presentation included worsening choreoathetoid movements due to TD/antipsychotic use, SLE-related neuropsychiatric sequelae, neurosyphilis, B12 deficiency, and possible fluoxetine-or bupropion-related choreiform movements. However, some items on this differential were rare sequelae of the purported medications, as olanzapine-induced TD has only been found to occur at the case report level.10 Despite the relative rarity of this diagnosis under these circumstances, the patient’s quetiapine was held at admission out of concern for worsening the patient’s movement disorder.

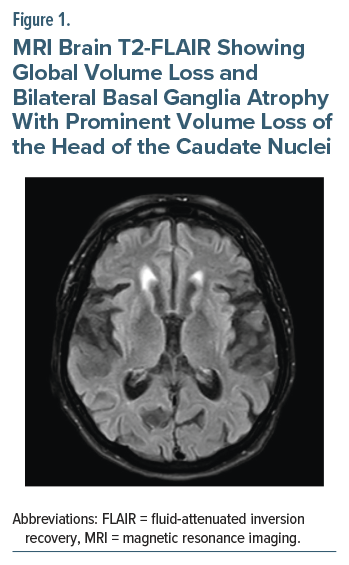

Chart review revealed previously performed magnetic resonance imaging of the brain 3 months prior that reported global volume loss and bilateral atrophy of the basal ganglia with prominent volume loss of the head of the caudate nuclei (Figure 1). It was also noted at a prior outpatient neurology visit that the patient was adopted, and her family history of neurological disorders was unknown. On examination, broad, nonsuppressible, continuous, flowing choreiform movements of all extremities were noted, as well as occasional abnormal facial movements and an underlying restlessness consistent with akathisia. Suspicion for HD or another neurodegenerative condition increased, and genetic testing was subsequently ordered. Genetic testing for HD was positive, with 43 CAG repeats noted.

Treatment. In the absence of quetiapine, the patient’s agitation and mood symptoms worsened considerably, which led to resuming quetiapine at her home dose of 50 mg 3 times/d due to minimal concern for worsening TD as well as the need to address her diagnosed bipolar disorder. Following this medication change, the patient’s mood improved considerably, and she remained calm and cooperative for the remainder of her admission. Bupropion and fluoxetine were subsequently discontinued to avoid worsening akathisia and concomitant use of cytochrome P450 (CYP) 2D6 inhibitors with vesicular monoamine transporter 2 (VMAT2) inhibitors such as valbenazine.11 As there are currently no treatments capable of altering the course of HD, plans were made to resume the patient’s valbenazine, which was complicated by the lack of availability of the medication in the hospital’s formulary as well as the patient’s refusal to switch to the available deutetrabenazine. The patient’s medical power of attorney was ultimately able to bring in the patient’s home medications, and the patient was discharged with plans to continue the management of her HD at an outpatient neurology clinic.

Discussion

Mania and psychosis have both been observed to be prevalent in patients with HD, with psychiatric manifestations of the disease sometimes being the first indication of HD.6,12 The delay in manifestation between the psychiatric and motor manifestations of HD can sometimes lead to diagnosis of bipolar disease, especially since many of the symptoms commonly seen in manic episodes (disinhibition, irritability, impulsivity) are also common psychiatric symptoms of HD.1,6,12 Similarly, delusions and paranoia seen in HD patients can be misdiagnosed as schizophrenia and treated with neuroleptics, which can then lead to the misdiagnosis of TD at the first sign of involuntary movements in these patients.6,12

In this case, the diagnosis was complicated by a previously seemingly established diagnosis of TD, as well as a lack of family history due to the patient’s history of adoption. As stated previously, HD is most often tested for and diagnosed based on the presence of positive family history and chorea. Due to the lack of available information on the patient’s biological family as well as the overlapping psychiatric and movement manifestations of HD and TD, there was low suspicion for the consideration of HD prior to this admission. Her age also likely contributed to a delay in diagnosis, as the mean age at onset for symptoms for HD is 45 years. It should be noted that delayed onset of HD is seen in close to 25% of patients, with these patients often first manifesting symptoms after the age of 50 years.1

There is currently no curative treatment for HD. Treatment revolves presently around managing the symptoms, which usually includes the use of VMAT inhibitors, such as tetrabenazine and valbenazine, to manage the chorea and atypical neuroleptics for psychiatric symptoms, both of which the patient was taking before admission.1,12–14 However, during her hospital admission, there was a significant delay in retrieving her home medications as well as in resuming her quetiapine due to diagnostic uncertainty at the time. Additionally, the missed diagnosis of HD led to delay in receiving genetic counseling and considerable progression of the disease by the time the diagnosis was made.

Importantly, the patient also had 2 biological daughters with whom she is no longer in contact and who therefore currently have an unknown gene status. The patient’s current number of CAG repeats was 43, and since the anticipation phenomenon is typically only seen in the paternal line of inheritance, if inherited, it is unlikely to present at an earlier age in her children. That said, as there is currently no method with which to contact her biological children, they will likely face similar diagnostic challenges in the absence of their knowledge of this diagnosis.

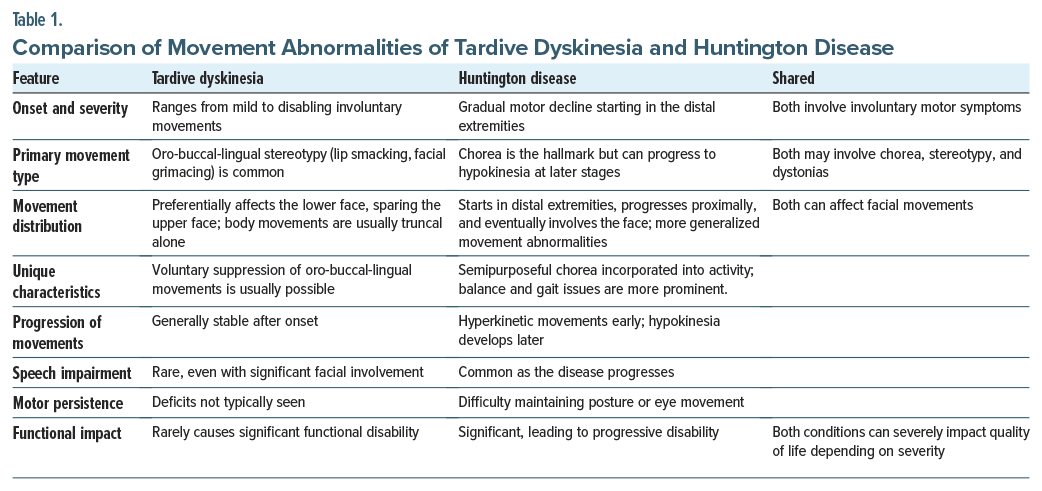

This case raises a fundamental question—in the absence of a clear distinguishing history (long-term use of neuroleptics for TD and family history for HD), are the movement disorders seen with HD and TD clinically distinguishable? The severity of TD can range from mild involuntary movements to disabling and can manifest with stereotypy, dystonia, akathisia, tics, tremors, myoclonus, chorea, parkinsonism, and even pain.7–9 The classic and most common form of TD is best categorized as “oro-bucco-lingual stereotypy,” often involving lip smacking and facial grimacing.7–9 Many patients can also have limb stereotypies and akathisia.7,9 However, isolated tardive chorea is rare, as it is most often seen accompanying stereotypy in the face.9 It should also be noted that TD usually spares the upper face and preferentially affects the lower face (mouth and tongue).5 TD is also not thought to cause significant functional disability in most affected patients, as the movements can typically be suppressed with effort.

Although the most widely recognized feature of HD is chorea, patients can have many overlapping features, including chorea, tics, stereotypy, and dystonias.1,4 The progression of motor movements typically starts in the distal extremities, spreads more proximally with progression, and can eventually involve the face.1,4,5 Initially, movements tend to be more hyperkinetic with involuntary chorea, but hypokinesia can appear in later stages of the disease.1 There is also often a semipurposeful movement aspect to the chorea seen in HD in which involuntary movements are incorporated into natural activity, which is typically not seen in the choreoathetoid movements of TD.8,15 Speech impairment can often also develop during the disease, which is not frequently seen in TD even with significant facial movements.4,5,8,15 Finally, motor impersistence is often a finding that is more unique to HD, in which patients cannot maintain a sustained posture or eye movement for longer than several seconds.15,16 Table 1 compares the movement abnormalities of TD with that of HD.

From the perspective of objective testing, genetic testing can be used most definitively to confirm the diagnosis through an adequate number of repeats. MRI can also be a helpful adjunct and essential tool in guiding the diagnosis. MRI in HD frequently shows striking volume loss, most prominently in the caudate and putamen. MRI has been utilized in the past for monitoring the progression of HD and response to therapies in clinical trials.17,18 Although TD has also been seen to correlate with volume loss of the caudate and other areas of the basal ganglia on some occasions, the evidence on this matter is sparse and would suggest that MRI remains a valuable diagnostic tool for HD.19–21 Still, it could prove a worthwhile pursuit in the future to better characterize the MRI changes seen in patients with TD on a larger scale, especially given the similarities in symptomology and management between the 2 conditions.

Conclusion

HD can prove a diagnostic challenge due to the psychiatric comorbidities and complications seen with the disease, which can result in the complicating factor of a history of antipsychotic intake and misdiagnosis of TD. While a patient with HD can have comorbid TD, it is essential to make note of the specific abnormal movements seen to arouse appropriate clinical concern for a possible HD diagnosis in the event of suggestive symptoms and disease course. Though the 2 diagnoses share similar patterns of abnormal movements, HD often presents with a greater degree of functional impairment, an involvement of speech, a semipurposeful nature to the limb movements, and motor persistence that can distinguish it from the broad spectrum of syndromes seen in TD. Inclusion of HD in the differential for new emergence of involuntary movements in patients with a diagnosed psychiatric disorder can help ensure appropriate and timely identification of the disease with earlier diagnostic and prognostic understanding for the patient.

Article Information

Published Online: December 9, 2025. https://doi.org/10.4088/PCC.25cr04020

© 2025 Physicians Postgraduate Press, Inc.

Prim Care Companion CNS Disord 2025;27(6):25cr04020

Submitted: June 13, 2025; accepted August 20, 2025.

To Cite: Kotta A, Ashraf S, Khan M, et al. Diagnostic challenges in distinguishing Huntington disease from tardive dyskinesia. Prim Care Companion CNS Disord 2025;27(6):25cr04020.

Author Affiliations: Department of Psychiatry, University of Texas Southwestern Medical Center, Dallas, Texas (Kotta, Wickramage, Rafferty); Department of Psychiatry, JPS Health Network, Fort Worth, Texas (Ashraf, Khan).

Corresponding Author: Sahar Ashraf, MD, Department of Psychiatry, JPS Health Network, Fort Worth, Texas ([email protected]).

Relevant Financial Relationships: None.

Funding/Support: None.

Patient Consent: Written informed consent was obtained from the patient to publish the case report, and information has been de-identified to protect patient anonymity.

References (21)

- Ajitkumar A, De Jesus O. Huntington Disease. In: StatPearls. StatPearls; 2024.

- Jevtic SD, Provias JP. Case report and literature review of Huntington disease with intermediate CAG expansion. BMJ Neurol Open. 2020;2(1): e000027. PubMed CrossRef

- Rawlins MD, Wexler NS, Wexler AR, et al. The prevalence of Huntington’s disease. Neuroepidemiology. 2016;46(2):144–153. PubMed CrossRef

- Stoker TB, Mason SL, Greenland JC, et al. Huntington’s disease: diagnosis and management. Pract Neurol. 2022;22(1):32–41. PubMed CrossRef

- Grove M, Vonsattel JP, Mazzoni P, et al. Huntington’s disease. Sci Aging Knowledge Environ. 2003; 2003(43):dn3. PubMed CrossRef

- Snowden JS. The neuropsychology of Huntington’s disease. Arch Clin Neuropsychol. 2017;32(7):876–887. PubMed CrossRef

- Vasan S, Padhy RK. Tardive Dyskinesia. In: StatPearls; 2024.

- Hauser RA, Meyer JM, Factor SA, et al. Differentiating tardive dyskinesia: a video-based review of antipsychotic-induced movement disorders in clinical practice. CNS Spectr. 2022;27(2):208–217. PubMed CrossRef

- Waln O, Jankovic J. An update on tardive dyskinesia: from phenomenology to treatment. Tremor Other Hyperkinet Mov (N Y). 2013;3. CrossRef

- Choe YM, Kim SY, Choi IG, et al. Olanzapine-induced concurrent tardive dystonia and tardive dyskinesia in schizophrenia with intellectual disability: a case report. Clin Psychopharmacol Neurosci. 2020;18(4):627–630. PubMed CrossRef

- Kotlyar M, Brauer LH, Tracy TS, et al. Inhibition of CYP2D6 activity by bupropion. J Clin Psychopharmacol. 2005;25(3):226–229. PubMed CrossRef

- Rosenblatt A. Neuropsychiatry of Huntington’s disease. Dialogues Clin Neurosci. 2007;9(2):191–197. PubMed CrossRef

- Moondra P, Jimenez-Shahed J. Profiling deutetrabenazine extended-release tablets for tardive dyskinesia and chorea associated with Huntington’s disease. Expert Rev Neurother. 2024; 24(9):849–863. PubMed CrossRef

- Claassen DO, Philbin M, Carroll B. Deutetrabenazine for tardive dyskinesia and chorea associated with Huntington’s disease: a review of clinical trial data. Expert Opin Pharmacother. 2019;20(18): 2209–2221. PubMed CrossRef

- Lo DC, Hughes RE, eds. Neurobiology of Huntington’s Disease: Applications to Drug Discovery. CRC Press/Taylor & Francis: Boca Raton, Florida; 2011.

- Oh DS, Park ES, Choi SM, et al. Oromandibular dyskinesia as the initial manifestation of late-onset huntington disease. J Mov Disord. 2011;4(2): 75–77. PubMed CrossRef

- Bohanna I, Georgiou-Karistianis N, Hannan AJ, et al. Magnetic resonance imaging as an approach towards identifying neuropathological biomarkers for Huntington’s disease. Brain Res Rev. 2008;58(1): 209–225. PubMed CrossRef

- Negi RS, Manchanda KL, Sanga S. Imaging of Huntington’s disease. Med J Armed Forces India. 2014;70(4):386–388. PubMed CrossRef

- Sarró S, Pomarol-Clotet E, Canales-Rodríguez EJ, et al. Structural brain changes associated with tardive dyskinesia in schizophrenia. Br J Psychiatry. 2013; 203(1):51–57. PubMed

- Mion CC, Andreasen NC, Arndt S, et al. MRI abnormalities in tardive dyskinesia. Psychiatry Res. 1991;40(3):157–166. PubMed CrossRef

- Elkashef AM, Buchanan RW, Gellad F, et al. Basal ganglia pathology in schizophrenia and tardive dyskinesia: an MRI quantitative study. Am J Psychiatry. 1994;151(5):752–755. PubMed CrossRef

Enjoy this premium PDF as part of your membership benefits!