Lessons Learned at the Interface of Medicine and Psychiatry

The Psychiatric Consultation Service at Massachusetts General Hospital sees medical and surgical inpatients with comorbid psychiatric symptoms and conditions. During their twice-weekly rounds, Dr Stern and other members of the Consultation Service discuss diagnosis and management of hospitalized patients with complex medical or surgical problems who also demonstrate psychiatric symptoms or conditions. These discussions have given rise to rounds reports that will prove useful for clinicians practicing at the interface of medicine and psychiatry.

Prim Care Companion CNS Disord 2025;27(5):25f03967

Author affiliations are listed at the end of this article.

Have you ever been struck by how disabling dizziness can be to interpersonal relationships, work and academic activities, and happiness? Have you wondered why dizziness occurs and how it can be evaluated? Have you been uncertain about how best to manage dizziness with medications, physical interventions, and talking therapies? If you have, the following case vignette and discussion should prove useful.

CASE VIGNETTE

Ms A, a 39-year-old woman with generalized anxiety disorder and hemispheric migraines (diagnosed 5 years ago, with symptoms predominantly on the left side but occasionally bilateral), had daily headaches triggered by stress, physical exertion, exposure to cold, and her menstrual cycle.

One year ago while traveling, she experienced a severe earthquake and subsequently suffered from acute dizziness, nausea, and vomiting. Her dizziness failed to resolve despite resolution of her nausea; it impacted her balance, and her gait became unsteady. Moving her head quickly triggered nausea. Walking in dimly lit spaces required leaning on a wall or a person for balance to prevent falls (which occur at least once a week even when unprovoked). Vestibular testing failed to reveal benign paroxysmal positional vertigo (BPPV) or vestibular hypofunction.

What Is Meant by Dizziness?

“Feeling dizzy” is a complaint reported by 15%–20% of adults (ie, roughly 33 million people) every year in the United States.1,2 Moreover, dizziness accounts for 4% of all emergency department visits and 5% of primary care visits.3,4 However, the definition of dizziness varies from patient to patient and from physician to physician. Patients commonly describe this phenomenon as feeling “lightheaded,” “woozy,” “unsteady,” “off-balance,” or “faint.” When patients are prompted to clarify and elaborate on this feeling, additional descriptions include “The room is spinning around me” or “I feel as though I am going to pass out.” Patients may also report alterations in their cognitive ability, including feeling confused, disoriented, or anxious.5,6

What Distinguishes Dizziness From Fainting, Swooning, and Syncope?

Dizziness is a nonspecific symptom associated with myriad disorders and conditions (eg, vertigo, presyncope, syncope, disequilibrium, and lightheadedness).5,6 To distinguish among these, it is useful to obtain a detailed history, as well as to conduct a careful physical examination.7 When gathering the history, special attention should be paid to triggering or precipitating factors, as well as the frequency and duration of episodes.

Fainting, swooning, and syncope are characterized by a brief loss of postural tone and consciousness, which is often precipitated by situational triggers, including positional changes or cardiac arrhythmias. Common prodromes of fainting and syncope include cold sweats, nausea, blurred vision, and vomiting.8 Syncope often involves multiple organ systems and can be categorized into neurally mediated (reflex) syncope, orthostatic syncope, and cardiovascular syncope.

Which Anatomical Structures, Circuits, and Conditions Are Involved in Dizziness?

The anatomical structures associated with dizziness include the peripheral and central vestibular systems. The peripheral vestibular system is composed of the vestibule containing the otolith structures of the saccule and utricle, as well as the 3 perpendicular semicircular canals in combination with the vestibular portion of the eighth cranial nerve. The central vestibular system includes the brain stem and cerebellum as well as the vestibular cortex.9 Transient ischemic attacks/cerebrovascular accidents (CVAs), carotid artery disease, and carotid stenosis also cause dizziness.10,11

Several circuits integrate the input and output of this vestibular system and include the following pathways:

- Vestibular-spinal, which modulates posture, balance, and proprioception through the vestibulospinal reflexes;

- Vestibular-oculomotor, which coordinates eye movements with head movements through the vestibulo-ocular reflex that is formed by the connections among the afferent vestibular nerve, the vestibular nuclei in the pontomedullary region, and the oculomotor nuclei in the midbrain;

- Vestibular-cerebellar, which helps to coordinate motor control, modulate movement precision, and sensorimotor integration;

- Vestibular-thalamo-cortical, which can be identified by distinguishing between active and passive head movements, tilting the head in relation to gravity, and having the perception of the “visual vertical,” postural stability, self-motion perception, and spatial orientation;

- Vestibular-hippocampal, which can be activated during cold caloric irrigation testing that generates disorientation and feelings of self- rotation. Spatial memory and navigation also appear to be impacted by peripheral vestibular dysfunction12;

- Vestibular-cortical, which is wide ranging with a general right hemisphere dominance and redundancy. It is primarily centered around the parieto-insular vestibular cortex. Although it is not well understood, it is thought to be involved in whole-body movement and the sense of self-motion, motor control, spatial awareness, and visual vertical perception.13

Which Psychiatric and Neuropsychiatric Conditions Are Characterized by Dizziness?

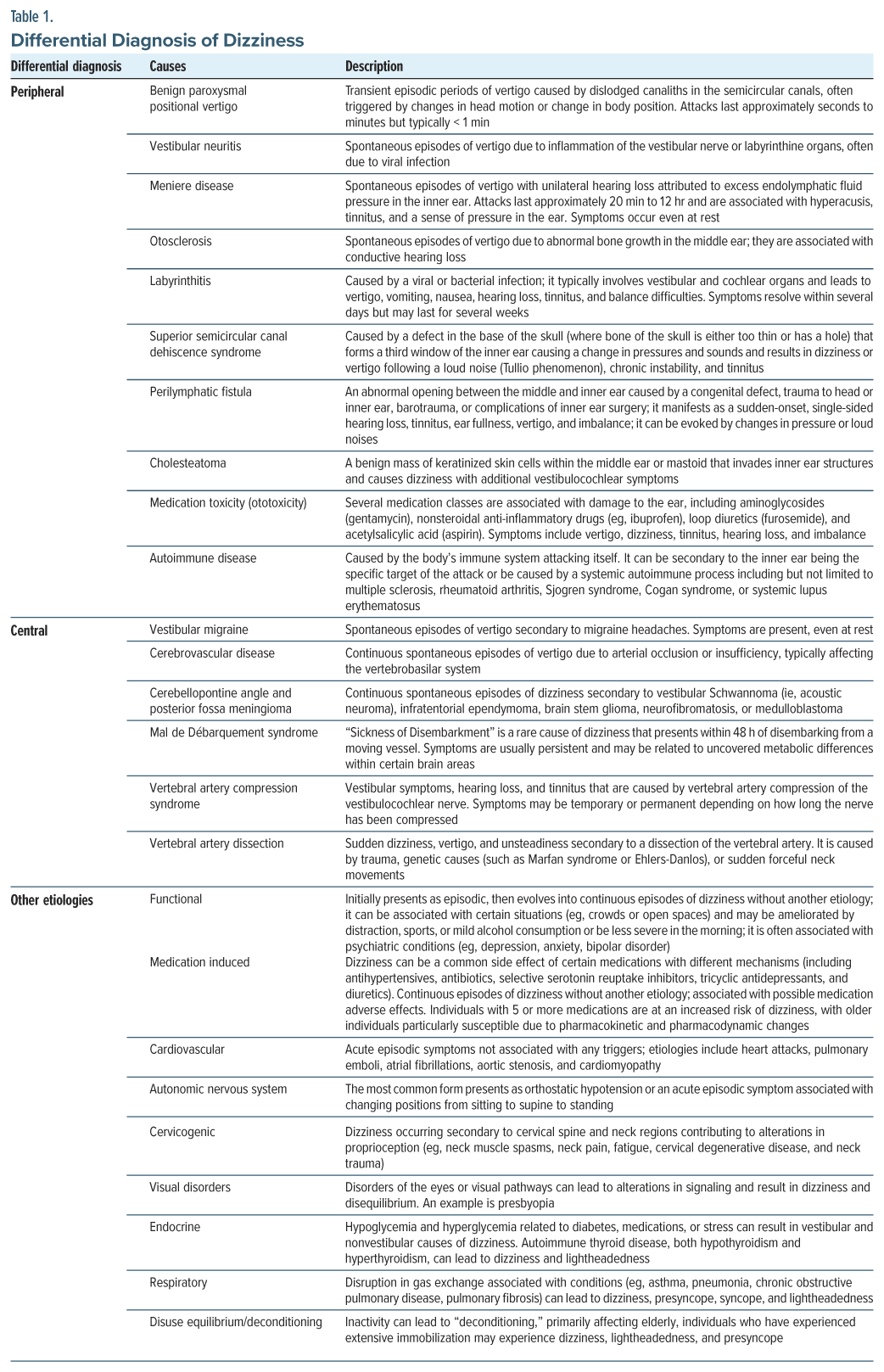

Unfortunately, the experience of dizziness does not always align with a specific physiological abnormality, and it may originate in vestibular and nonvestibular sources (eg, peripheral nerves and the cardiovascular system) (Table 1).14

Peripheral vestibular system causes. BPPV is one of the most common peripheral vestibular disorders, which often presents in people between the ages of 50 and 70 years (although it may occur in younger individuals who have suffered a traumatic brain injury [TBI]).7 BPPV is caused by the displacement of free-floating crystals (otoconia) within the semicircular canals. Changes in head position or specific body movements commonly trigger this phenomenon.14

Vestibular neuritis is the second most common cause of vertigo, which commonly affects patients between the ages of 30 and 50 years.7 Vestibular neuritis results from viral or bacterial infections that impact the vestibular nerve and result in atypical signals to the brain. The classic presentation of vestibular neuritis is sudden, severe dizziness that lasts for more than 24 hours (and up to 1 week). Severe rotatory vertigo may occur with associated nausea, oscillopsia, vomiting, difficulties with balance, and horizontally rotating spontaneous nystagmus to the nonaffected side or abnormal gait with a tendency to fall to the affected side.7 It is commonly mistaken for labyrinthitis; however, patients with vestibular neuritis do not experience hearing loss.9

The final peripheral vestibular cause of vertigo is Meniere disease. Meniere disease is a progressive, incurable disease marked by the classic triad of episodic vertigo, hearing loss, and tinnitus. Meniere disease results from an increased volume of inner ear fluid (endolymph) or endolymphatic hydrops.14 While Meniere disease can develop at any age, it arises most commonly in those between the ages of 20 and 60 years, often with unidirectional, horizontal-torsional nystagmus during episodes of vertigo.7

Central vestibular system causes. One-fourth of cases of dizziness originate in the central vestibular system (eg, vestibular nuclei, brain stem, cerebellum, spinal cord, and vestibular cortex) with the most common causes being vestibular migraine and vertebrobasilar ischemia. Individuals may present with disequilibrium and ataxia, rather than with true vertigo. Vertigo can be a presenting symptom of an impending CVA.7

While the mechanism of vestibular migraines is poorly understood, there is significant overlap with Meniere disease. Vestibular migraines usually occur between the ages of 20 and 50 years, and they are 3 times more likely to develop among women. Among children, vestibular migraines are one of the most common forms of episodic vertigo,7 and they may be associated with migraine features, eg, photophobia, phonophobia, headache, visual auras, and nausea.7

While the mechanism of persistent postural perceptual dizziness (PPPD) is also incompletely understood, significant psychological factors appear to be involved in its onset and persistence. PPPD is often marked by a waxing and waning pattern of dizziness, unsteadiness, and nonspinning vertigo. Certain triggers, specifically upright posture, self-motion, and active or passive motions in the context of complex visual stimuli, exacerbate PPPD.14

A more concerning etiology of dizziness is CVA. A CVA results from a lack of oxygen delivered to the central nervous system (CNS), and it can be categorized into ischemic and hemorrhagic forms. Ischemic strokes are the most common type, occurring when blood vessels that supply the CNS become blocked. Unlike ischemic strokes, hemorrhagic strokes result from bleeding in the brain. Patients may present with a sudden onset, marked neurological deficit (eg, numbness, weakness, confusion, difficulties with speech and vision, headache, dizziness, imbalance, or vertigo). Damage to the vestibular system may be temporary or permanent.14

Vertigo is usually the initial symptom in nearly half (48%) of patients who present with vertebrobasilar ischemia. Any occlusion in the vertebrobasilar system (brain stem, cerebellum, and inner ear) can result in vertigo along with weakness, dysarthria, diplopia, or limb clumsiness.7

Damage to the central or peripheral vestibular system can also present with neurological deficits (eg, dizziness, disequilibrium, hearing loss, tinnitus, pressure sensation, and increased sensitivity to sounds). Certain traumas (eg, blunt head trauma, blast injuries, deceleration trauma, barotrauma, or penetrating head trauma) have resulted in this form of damage. Symptoms associated with CVAs may resolve over time or require additional treatment depending on the injury’s location and severity.14

Nonvestibular causes of dizziness. Nonvestibular causes of dizziness occur outside of the inner ear and the associated pathways connecting to the brain stem and include the autonomic nervous system (ANS), endocrine system, and cardiovascular and respiratory systems.14

The ANS influences involuntary functions (eg, breathing, maintaining heart rate, digestion, salivation, and blood pressure with subsequent alterations that lead to perception of dizziness). One of the most common autonomic system dysfunctions that contributes to dizziness is orthostatic hypotension (OH) (eg, blood pressure that drops after transitioning from sitting to a standing position). While blood vessels in the lower half of the body normally constrict to maintain blood flow to the upper half of the body, there is a discrepancy in the case of OH, leading to inadequate blood flow from the heart to brain and causing dizziness or lightheadedness. Causes of OH vary (eg, older age, blood loss, use of medications, dehydration, and neurodegenerative diseases such as Parkinson disease).14

Endocrine conditions, specifically those related to blood sugar, can result in the subjective sensation of dizziness. Hypoglycemia and hyperglycemia (related to diabetes, medications, and stress) can result in both vestibular and nonvestibular dizziness.14 Cardiovascular disorders (eg, myocardial infarction, pulmonary emboli, atrial fibrillation, aortic stenosis, and cardiomyopathy) can lead to dizziness with lightheadedness and loss of consciousness along with disruption of gas exchange (eg, associated with asthma, pneumonia, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, and pulmonary fibrosis) with dizziness, lightheadedness, presyncope, and syncope.14

Psychiatric causes of dizziness. When an underlying medical etiology has not yet been established, the suspicion for psychogenic dizziness (eg, related to anxiety or depression) often increases.14 The subjective experience of dizziness more frequently correlates with psychological factors (eg, psychological distress, phobic and somatic anxiety traits, avoidance, autonomic arousal, social anxiety/stigma, and fears of vertigo) than objective evidence of physiological dysfunction.15 Stress, perceptual stimuli, or social situations bring on dizziness that results in subsequent avoidance. Panic disorder overlaps phenomenologically with vestibular dysfunction (eg, behavioral restriction, phobic avoidance, and symptomology [ie, sweating, nausea, and dizziness]). Relative to the general population, rates of panic disorder, major depressive disorder, and somatic symptom disorder are elevated in patients with dizziness.15

Among veterans with posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD), vestibular symptoms (eg, dizziness, disorientation, and/or postural imbalance) are commonly reported in crowded environments, such as shopping malls and grocery stores.16 Veterans with PTSD, particularly those with higher levels of avoidance, report more dizziness- related functional impairment. Moreover, there may be an interactive effect of anxiety and vestibular impairment, and TBI may play a contributory role in vestibular symptoms among veterans with PTSD.

Psychiatric treatment of dizziness includes behavioral therapy aimed at decreasing arousal to the identified stimulus, as well as pharmacologic interventions that decrease acute anxiety and prevent onset of downstream anxiety.17 It is essential to explore the patient’s narrative related to episodes of dizziness and take an integrative and individualized approach to management. Psychotropic medications (eg, selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors [SSRIs]) can play a role in treatment; however, many psychotropic medications can cause and/ or exacerbate dizziness (eg, quetiapine, an atypical antipsychotic, and trazodone, an agent used to manage insomnia, can cause OH, ie, dizziness that occurs with positional change).

How Might Dizziness Interfere With Intrapsychic and Interpersonal Functioning and With Academic and Work Performance?

Vestibular impairment has been linked to cognitive dysfunction across a variety of domains, both spatial and nonspatial.13 Subjective assessment of cognitive failures, including forgetfulness, distractibility, and interrupted processing of sequences of cognitive and motor actions, has revealed that patients with vestibular dysfunction (including vestibular migraine, Meniere disease, BPPV, and PPPD) had statistically worse cognitive impairment than matched controls. The impairment was correlated with both the duration and severity of symptoms, but reassuringly, treatment improved the subjective impairment.18–20

Dizziness has also been linked to pervasive social and occupational dysfunction with nationally representative survey participants reporting increased medical utilization, taking more sick leave, or having to change jobs (or quit their jobs) as a result of their symptoms, and over half of participants reporting decreased work efficiency in addition to social life disruption.21,22 In the United States, patients with vestibular vertigo were found to have an 8-fold higher risk of “serious difficulty concentrating or remembering” as well as a 4-fold increased odds of activity limitation due to difficulty remembering or confusion.23

How Might Dizziness Be Evaluated?

History. Determining the etiology for dizziness (eg, peripheral or central causes) starts with obtaining a thorough history. Establishing elements, such as timing (eg, onset, duration, and evolution of symptoms) and triggers (eg, situations, movements, and actions) that provoke symptoms, are vital. A helpful mnemonic used to guide assessment of dizziness is “TiTrATE” (ie, Timing of symptoms, Triggers that provoke symptoms, and a Targeted Examination). Following a thorough history, dizziness can be characterized as episodically triggered, spontaneous and episodic, or continuously vestibular. The characterization can further lend to diagnosis of an underlying peripheral or central etiology.7

Episodic triggered symptoms involve brief episodes of intermittent dizziness (lasting seconds to hours) that are provoked by head motion or a change in body position. Common etiologies include BPPV.7 Lasting slightly longer are spontaneous episodic symptoms that last for seconds to days and are not linked with a trigger. Etiologies of this type include Meniere disease, vestibular migraine, and psychiatric diagnoses, such as anxiety disorders. Symptoms associated with lying down are more likely to be vestibular.7 Continuous vestibular symptoms are associated with persistent dizziness (ie, lasting days to weeks), and they may be associated with traumatic or toxic exposures. Classic symptoms include continuous dizziness or vertigo associated with nausea, vomiting, nystagmus, gait instability, and head-motion intolerance. In the absence of trauma or toxic exposures, vestibular neuritis or central etiologies are the most likely culprit.7

Physical examination. Following a thorough history, a physical examination (including a cardiac and neurological evaluation, with particular attention to the head, ears, eyes, nose, and throat) should be performed. Gait should be assessed with a Romberg examination. Individuals with an unsteady gait should be assessed for peripheral neuropathy; a positive Romberg test suggests abnormalities with proprioception. While most patients with dizziness have a normal physical examination, this component of practice should not be neglected.7

In addition, measurement of blood pressure should be conducted in the standing and supine positions. OH is defined by a 20-mm Hg drop in systolic blood pressure or a 10-mm Hg drop in diastolic blood pressure or a 30- beat/minute rise in pulse rate when transitioning from the supine to standing position for approximately 1 minute.7

HINTS evaluation. The HINTS (head-impulse, nystagmus, test of skew) examination can further refine the differential diagnosis and help to distinguish a possible stroke (central etiology) from an acute vestibular syndrome (peripheral etiology). During the head-impulse portion, a patient’s head is thrust 10° to the right, followed by thrust to the left, while the individual’s eyes remain fixed on the examiner’s nose. If a saccade occurs, the etiology is most likely peripheral, with no eye movement suggestive of a central etiology.7

When evaluating for nystagmus, the patient should follow the examiner’s finger as it moves slowly to the left and the right. A peripheral cause, such as vestibular neuritis, is usually present if there is a spontaneous unidirectional horizontal nystagmus the worsens when gazing in the direction of the nystagmus. Spontaneous nystagmus, which is predominantly vertical or torsional, or gaze-evoked bidirectional nystagmus are more suggestive of a central etiology. An etiology related to a central pathology is often associated with nystagmus that changes direction less than half the time, and it can be suppressed with fixation.7

When evaluating the test of skew, the patient is asked to look straight ahead, then cover and uncover each eye. An abnormal result involves vertical deviation of the covered eye after it has been uncovered. While this test is less sensitive for determining a central etiology, an abnormal result is quite specific for brain stem involvement.7

Dix-Hallpike maneuver. BPPV is diagnosed when there is transient upbeat-torsional nystagmus during the Dix- Hallpike maneuver in combination with a history that is consistent with timing and triggers associated with BPPV. An individual’s head is turned at a 45° angle towards the ear while seated on an examination table. If the patient develops nystagmus while their head is turned to the right ear during this maneuver, this is suggestive of the problem being within the right semicircular canal. A negative result does not rule out BPPV if the history related to timing and triggers is consistent with BPPV. If nystagmus occurs without a typical history of BPPV, a central etiology for dizziness may be more likely.7

Laboratory testing and imaging. The assessment of dizziness does not typically require extensive laboratory testing and imaging unless a specific etiology is suspected. Individuals with certain chronic medical conditions (eg, diabetes and hypertension) may require monitoring of blood glucose and electrolytes. Symptoms that are suggestive of cardiac disease should prompt Holter monitoring, electrocardiography, and potentially carotid Doppler testing.7

Imaging is not typically indicated unless an abnormal neurologic finding (eg, asymmetric or unilateral hearing loss) is discovered that would warrant a computed tomography or magnetic resonance imaging scan to further evaluate for cerebrovascular disease. If hearing loss with vertigo is present and neuroimaging is normal, Meniere disease should be suspected.7

What Can We Learn From How Dizziness Is Portrayed in Television and the Movies?

Dizziness is a broad term that is often used to describe symptoms of lightheadedness and vertigo,24 which can each arise from different etiologies. In movies, dizziness is often portrayed through visual effects (utilizing the “vertigo effect,” a camera technique immortalized by Alfred Hitchcock in a movie of the same name). In the “vertigo effect,” the foreground remains static while the background shrinks or expands, creating disorientation. This effect has also been used in The Walk (a movie about a high-wire walk between the World Trade Center’s towers), Lord of the Rings (where Frodo becomes disoriented as he becomes aware of the spiritual forces swirling about him), and Jaws (when a surfing teen is shown underwater as he is attacked suddenly by a great white shark) to portray destabilizing emotions (eg, panic, fear) and to evoke an elevated heart rate, diaphoresis, disorientation, and dizziness.

How Can Control of Intense Emotions Be Taught?

During the rigorous training of elite forces, “mental toughness” is sought25; moreover, the management of emotional responses to adverse circumstances (eg, circumventing dizziness) is taught to new recruits by repeatedly exposing them to adversity. Master Resilience Training for Army Noncommissioned Officers embraces a multidisciplinary approach, involving cognitive- behavioral therapy that minimizes catastrophic thinking and facilitates problem-solving in real time.26,27 These cognitive techniques may counteract panic or fear and associated dizziness. Although dizziness usually resolves within several weeks of mild TBIs, it may persist and require a higher level of specialty care, such as that provided in a TBI-focused clinic.28 Numerous articles have linked psychiatric illnesses (eg, anxiety, depression) to dizziness.2,4 Unfortunately, although treatment for both anxiety/depression and dizziness involves use of SSRIs, these agents may not be accessible to currently enlisted service members.29

What Happened to Ms A?

Ms A participated in 3 months of vestibular physical therapy, which led to some symptom improvement. She was encouraged to continue performing exercises at home. Her working diagnosis was PPPD.

Conclusion

The case of Ms A illustrates that the diagnosis and treatment of dizziness can be complex and interferes with interpersonal relationships, work, academic functioning, and one’s sense of well-being. Dizziness also increases medical utilization, leads to taking more sick leave, and decreases work efficiency. Dizziness is a nonspecific symptom that is associated with myriad disorders and conditions (eg, vertigo, presyncope, syncope, disequilibrium, lightheadedness). The evaluation of dizziness often involves a physical examination, laboratory testing, and imaging studies and typically guides treatment.

Article Information

Published Online: September 18, 2025. https://doi.org/10.4088/PCC.25f03967

© 2025 Physicians Postgraduate Press, Inc.

Submitted: May 17, 2025; accepted June 11, 2025.

To Cite: Rustad JK, Braford M, Nguyen E, et al. Dizziness: an approach to diagnosis and treatment. Prim Care Companion CNS Disord 2025;27(5):25f03967.

Author Affiliations: Geisel School of Medicine at Dartmouth, Lebanon, New Hampshire (Rustad); Larner College of Medicine at University of Vermont, Burlington, Vermont (Rustad); Burlington Lakeside VA Community Based Outpatient Clinic, Burlington, Vermont (Rustad); White River Junction VA Medical Center, White River Junction, Vermont (Rustad); Department of Psychiatry, Lewis Gale Medical Center, Salem, Virginia (Braford); Virginia Commonwealth University School of Medicine, Richmond, Virginia (Nguyen); Harry S Truman Veteran’s Hospital, Columbia, Missouri (Boone); University of Missouri Medical School, Columbia, Missouri (Boone); Wright State Boonshoft School of Medicine, Dayton, Ohio (Weber); Wright Patterson AFB, Ohio (Weber); Walter Reed National Military Medical Center, Bethesda, Maryland (Ford); Department of Psychiatry, Massachusetts General Hospital/Harvard Medical School, Boston, Massachusetts (Stern).

Corresponding Author: James K. Rustad, MD, Department of Psychiatry, Geisel School of Medicine at Dartmouth, Dartmouth-Hitchcock Medical Center, One Medical Center Dr, Lebanon, NH 03756 ([email protected]).

Relevant Financial Relationships: Dr Rustad is employed by the US Department of Veterans Affairs, but the opinions expressed in this article do not reflect those of the Department of Veterans Affairs. Dr Braford has no disclosures to discuss, but the opinions expressed in this article do not reflect those of Lewis Gale Medical Center. Dr Nguyen has no disclosures to discuss, but the opinions expressed in this article do not reflect those of Virginia Commonwealth University School of Medicine. Dr Boone is employed at the US Department of Veteran’s Affairs, but the views expressed are only reflective of her own. Dr Weber: The views expressed in this article reflect the results of research conducted by the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the official policy or position of the US Air Force, Department of Defense, nor the US Government. Dr Ford: The views expressed in this article reflect the results of research conducted by the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the official policy or position of the US Army, Defense Health Agency, Department of Defense, nor the US Government. Dr Stern has received royalties from Elsevier for editing textbooks on psychiatry.

Funding/Support: None.

Clinical Points

- Dizziness is a common complaint; however, the definition of dizziness varies from patient to patient and from physician to physician.

- Dizziness can be divided into the peripheral (comprised by the vestibule containing the otolith structures of the saccule and utricle, as well as the 3 perpendicular semicircular canals in combination with the vestibular portion of the eighth cranial nerve) and central (which includes the brain stem, cerebellum, and the vestibular cortex vestibular systems).

- A helpful mnemonic used to diagnose dizziness is “TiTrATE” (Timing of symptoms, Triggers that provoke symptoms, and a Targeted Examination).

- While dizziness can be psychiatric in nature, the most common reason for this condition is mild traumatic brain injury.

- Psychiatric treatment of dizziness includes behavioral therapy aimed at decreasing arousal to the identified stimulus, as well as pharmacologic interventions that decrease acute anxiety and prevent onset of downstream anxiety.

References (29)

- Kerber KA, Callaghan BC, Telian SA, et al. Dizziness symptom type prevalence and overlap: a US nationally representative survey. Am J Med. 2017;130(12):1465.e1–1465.e9. PubMed

- Neuhauser HK. The epidemiology of dizziness and vertigo. Handb Clin Neurol. 2016;137:67–82. PubMed CrossRef

- Saber Tehrani AS, Coughlan D, Hsieh YH, et al. Rising annual costs of dizziness presentations to U.S. emergency departments. Acad Emerg Med. 2013;20(7):689–696. PubMed CrossRef

- Post RE, Dickerson LM. Dizziness: a diagnostic approach. Am Fam Physician. 2010;82(4):361–369. PubMed

- Reilly BM. Dizziness. In: Walker HK, Hall WD, Hurst JW, eds. Clinical Methods: The History, Physical, and Laboratory Examinations. 3rd ed. Butterworths; 1990. Chapter 212. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK325/

- Barton J. Approach to the patient with dizziness. UpToDate. https://pubmed.ncbi.nih.gov/28739195/

- Muncie HL, Sirmans SM, James E. Dizziness: approach to evaluation and management. Am Fam Physician. 2017;95(3):154–162. PubMed

- Grossman SA, Badireddy M. Syncope. [Updated 2023 Jun 12]. In: StatPearls [Internet]. StatPearls Publishing; 2025. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK442006/

- Pérez-Fernández N, Ramos-Macías A. Recent advances in the diagnosis and treatment of vestibular disorders. J Clin Med. 2023;12(16):5281. PubMed

- Whitman GT. Dizziness. Am J Med. 2018;131(12):1431–1437. PubMed CrossRef

- Heck D, Jost A. Carotid stenosis, stroke, and carotid artery revascularization. Prog Cardiovasc Dis. 2021;65:49–54. PubMed CrossRef

- Smith PF, Zheng Y. From ear to uncertainty: vestibular contributions to cognitive function. Front Integr Neurosci. 2013;7:84. PubMed CrossRef

- Smith LJ, Wilkinson D, Bodani M, et al. Cognition in vestibular disorders: state of the field, challenges, and priorities for the future. Front Neurol. 2024;15:1159174. PubMed CrossRef

- Keith B, Rizk H. Causes of dizziness. vestibular.org. https://vestibular.org/wp-content/uploads/2024/10/Causes-of-Dizziness_11_cobrandable.pdf. Accessed December 15, 2024.

- Simon NM, Pollack MH, Tuby KS, et al. Dizziness and panic disorder: a review of the association between vestibular dysfunction and anxiety. Ann Clin Psychiatry. 1998;10(2):75–80. PubMed CrossRef

- Haber YO, Chandler HK, Serrador JM. Symptoms associated with vestibular impairment in veterans with posttraumatic stress disorder. PLoS One. 2016;11(12):e0168803. PubMed CrossRef

- Pallais JC, Schlozman SC, Puig A, et al. Fainting, swooning, and syncope. Prim Care Companion CNS Disord. 2011;13(4):PCC.11f01187. PubMed

- Donaldson LB, Yan F, Liu YF, et al. Does cognitive dysfunction correlate with dizziness severity in patients with vestibular migraine? Am J Otolaryngol. 2021;42(6):103124. PubMed CrossRef

- Rizk HG, Sharon JD, Lee JA, et al. Cross-sectional analysis of cognitive dysfunction in patients with vestibular disorders. Ear Hear. 2020;41(4):1020–1027. PubMed CrossRef

- Chari DA, Liu YH, Chung JJ, et al. Subjective cognitive symptoms and Dizziness Handicap Inventory (DHI) performance in patients with vestibular migraine and Menière’s disease. Otol Neurotol. 2021;42:883–889. PubMed CrossRef

- Bronstein AM, Golding JF, Gresty MA, et al. The social impact of dizziness in London and Siena. J Neurol. 2010;257(2):183–190. PubMed CrossRef

- Neuhauser HK, Radtke A, von Brevern M, et al. Burden of dizziness and vertigo in the community. Arch Int Med. 2008;168(19):2118–2124. PubMed CrossRef

- Bigelow RT, Semenov YR, du Lac S, et al. Vestibular vertigo and comorbid cognitive and psychiatric impairment: the 2008 National Health Interview Survey. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2016;87(4):367–372. PubMed CrossRef

- Dizziness. MedlinePlus [Internet]. Bethesda (MD): National Library of Medicine (US); 2023. https://medlineplus.gov/heartattack.html

- Gucciardi F, Lines R, Ducker K, et al. Mental toughness as a psychological determinant of behavioral perseverance in Special Forces selection. Sport Exerc Perform Psychol. 2020;10:164–175.

- Ledford AK, Beckner ME, Conkright WR, et al. Psychological and physiological changes during basic, underwater, demolition/SEAL training. Physiol Behav. 2022;257:113970. PubMed CrossRef

- Reivich K, Seligman MEP, McBride S. Master resilience training in the U.S. Army. Am Psychol. 2011;66(1):25–34. PubMed CrossRef

- Ahmad M, Safdar N, Salik S, et al. The frequency of dizziness among mild to moderate traumatic brain injury patient. Found Univ J Rehab Sci. 2024;4:58–61. CrossRef

- Staab JP, Ruckenstein MJ. Chronic dizziness and anxiety: effect of course of illness on treatment outcome. Arch Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2005;131(8):675–679. PubMed CrossRef

Enjoy this premium PDF as part of your membership benefits!