Lessons Learned at the Interface of Medicine and Psychiatry

The Psychiatric Consultation Service at Massachusetts General Hospital sees medical and surgical inpatients with comorbid psychiatric symptoms and conditions. During their twice-weekly rounds, Dr Stern and other members of the Consultation Service discuss diagnosis and management of hospitalized patients with complex medical or surgical problems who also demonstrate psychiatric symptoms or conditions. These discussions have given rise to rounds reports that will prove useful for clinicians practicing at the interface of medicine and psychiatry.

Prim Care Companion CNS Disord 2025;27(4):25f03928

Author affiliations are listed at the end of this article.

Have you been surprised by how often unexplained somatic symptoms have arisen in active-duty military personnel and in veterans? Have you been unsure about how vigorously to evaluate difficult to-diagnose somatic symptoms? Have you wondered whether psychological stress or posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) has predisposed individuals to develop a functional neurological disorder (FND)? Have you been uncertain about who should treat (and how) FNDs? If you have, the following case vignette and discussion should prove useful.

CASE VIGNETTE

Mr A, a 19-year-old man, became lightheaded and had a syncopal episode while standing in military formation following a 2-mile training run in the desert. Upon awakening, he was unable to move his limbs. Fortunately, within an hour, his ability to move his arms returned, although movement of his legs remained impaired. He endorsed sensory changes from his thighs to his toes bilaterally and denied disturbances of bowel and bladder function.

Mr A’s mental status and cranial nerve examinations were normal, as were his motor, sensory, reflex, and coordination testing of the upper extremities. Examination of his lower extremities revealed normal tone and bulk, but power testing showed a diffuse pattern of weakness (1/5) during hip flexion, knee flexion, knee extension, ankle dorsiflexion, and ankle plantar flexion. Deep tendon reflexes were 2+ at his ankles and knees. The Babinski response was flexor. To light touch and pinprick, Mr A reported a symmetric 25% decrement in sensation from his mid thighs to his toes. Vibration sensation was normal. The remainder of his examination was deferred. Evaluation included a noncontrast head computed tomography (CT) scan, a magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) scan of the brain and all segments of the spinal cord, cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) analysis, and routine blood tests; all were unremarkable.

DISCUSSION

What Is the Differential Diagnosis of Somatic Symptoms That Elude a Definitive Diagnosis?

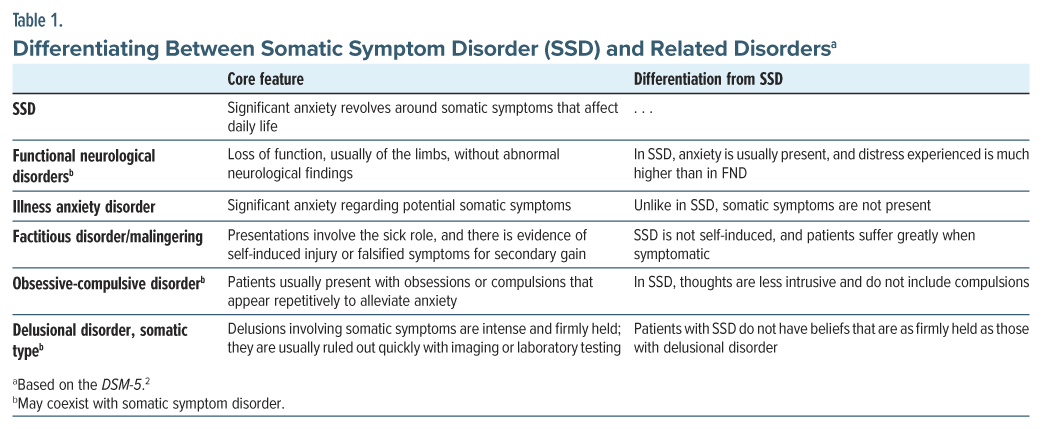

Somatic symptom disorder (SSD) is a collection of signs and symptoms (ie, a clinical syndrome) in a person who struggles with somatic symptoms as well as thoughts, feelings, and behavioral manifestations that are out of proportion to the symptoms they are experiencing.1 Research has shown that the impetus for SSD is anxiety, which can distinguish SSDs from related disorders (Table 1).2 Those who become anxious about symptoms and ruminate excessively over bodily sensations often engage in repetitive behaviors to address and relieve this anxiety.3

What Is Meant By a FND?

FNDs are conditions in which the primary pathophysiologic processes involve alterations in the function of brain networks rather than abnormalities of brain structures.4 FNDs have been defined as clinical syndromes that consist of symptoms and signs with alterations in motor, sensory, or cognitive performance that are distressing or impairing and are manifest by variable performance within and between tasks.4 The most common presentations of FND are functional seizures (also called dissociative or psychogenic nonepileptic seizures [PNES]) and functional movement disorders, including paresis. Other common manifestations are somatosensory or visual symptoms and speech disorders.

Who Develops FNDs?

The age of patients diagnosed with FNDs is highly variable (4–94 years).5,6 Most of those with FND are women (60%–80%), although the gap between genders is less pronounced in early and late life.7,8 FND is multifactorial, and its risk factors in adults include recent psychological stressors and a history of adverse childhood experiences (ACEs), especially neglect.9 Women have a higher frequency of ACEs than do men, which may explain their having a higher prevalence of FNDs,10 although women are also more likely to seek health care, and other disorders (eg, multiple sclerosis [MS]) are more common in women. Risk factors for FNDs in children include family dysfunction, bullying, and perceived peer pressure, rather than abuse.11 FNDs are commonly comorbid with depression, anxiety, traumatic stress disorders, and cluster B personality traits; 12,13 however, psychiatric comorbidities are not unique to FNDs, and they are common in neurological disorders.4

FNDs also coexist with other functional somatic disorders, including chronic pain and irritable bowel syndrome, implying that there may be a shared pathophysiology and/or risk factors.14–16 Interestingly, pain and fatigue may have more effect on quality of life than the FND symptoms themselves.17,18

Members of the US military services may be at increased risk for FNDs because of the increased prevalence of comorbid mental health conditions; exposure to physical, emotional, or sexual trauma; young age; and low socioeconomic status.19 When the incidence of FNDs was evaluated in active-duty US Armed Forces members between 2000 and 2018, a crude overall incidence rate of FND was 29.5 per 100,000 person-years, which is approximately 2.5–7.4 times higher than estimates reported for those in the general US population. Moreover, the overall rates of FNDs among service members with a history of depression or PTSD were more than 10 times higher than among individuals without such a history.19

Throughout history, exposure to trauma (particularly combat-related trauma) has been associated with the onset of FNDs.20,21 FNDs were probably more prevalent among American Civil War soldiers, especially among those diagnosed with epilepsy or paralysis.22 US Army historical data revealed an estimated incidence of FNDs of 15.3 per 10,000 person-years at the end of World War I.23 After World War I, the occurrence of FNDs among British, French, and German forces was also studied.24 The condition was believed to be less common during and after World War II than during World War I, although its prevalence increased again during the Korea and Vietnam conflicts. The incidence of FNDs in the Korea-Vietnam era reached a peak in 1975 at 9.5 cases per 10,000 person-years, and it has been declining slowly (based on 1991 estimates) since.20

Why Do FNDs Develop?

Since the time of Briquet, Breuer, and Freud (more than a century ago), FNDs were thought to develop only after a trauma, and that the symptom(s) was(were) a physical manifestation of the unconscious, unprocessed trauma history. Therefore, interventions focused on “treating” the underlying trauma. However, additional research has led to the conclusion that there is no single precipitant for the onset of FNDs.25 In fact, the revised Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fifth Edition (DSM-5) criteria no longer require a stressor for the diagnosis of a FND.26 For example, individuals with chronic conditions, such as migraine headaches or epilepsy, have an increased risk of developing FND, while acute conditions, such as infections or injuries, could trigger the condition.27 The age of those with FNDs is highly variable, with a mean age of 39.6 years.28 Women (72.6%) are more likely to be diagnosed than men, and they exhibit symptoms almost 2 years earlier.

Regarding the etiology of FNDs, predisposing factors include genetics, personality, and adverse experiences.29 Precipitating factors include physical injuries, psychological trauma, and life stressors. Perpetuating factors include psychiatric disorders, deconditioning, illness beliefs, social benefits, and plastic central nervous system changes.

What Do Individuals With FNDs Think Is Responsible for Their Symptoms?

Contrary to research that links a variety of psychosocial risk factors to the development of FNDs, patient-centered studies have repeatedly demonstrated that patients do not attribute their symptoms to psychosocial or psychological factors. When comparing cases of functional weakness to control populations with neurologically explainable weakness, both case and control groups mostly agreed that their symptoms were cyclic, had major consequences on their lives, and adversely affected their mood. Individuals with functional weakness were significantly less likely to believe that “stress or worry” might be causing their symptoms and tended to endorse all potential causes to a lesser extent than control populations, and only 12% of “cases” described a “primary” cause of their symptoms as being psychological. The most strongly held beliefs for the cause of their symptoms included an undiscovered physical cause, damage to the nervous system, and reversible changes to the nervous system.30

Relatedly, comparing cases of functional seizures with control populations diagnosed with epilepsy, those with functional seizures thought that psychological factors were less related to their illness than did their matched epileptic counterparts. Cases and controls ranked similarly low on scores of hypochondriasis and had similarly moderate scores of disease conviction and preoccupations with symptoms. In addition, those with functional seizures were more likely to score higher on the denial scale of the Illness Behavior Questionnaire, which indicated a greater tendency to deny life stressors and instead attribute problems to the effects of an illness. Lastly, those with functional seizures scored as having a greater external locus of control.31

When individuals with functional weakness and nonepileptic seizures were compared, both groups believed to a lesser extent that either a psychological cause or stress was responsible for their disease process compared to control populations. Those with functional weakness were less likely than those with epileptic seizures to attribute a psychological cause to their condition or believe that treatment would be effective for the condition.32

How Much Time Typically Passes Between the Onset of Symptoms and the Diagnosis of FNDs?

In a single-center German cohort of 313 patients designed specifically to evaluate for treatment delay of PNES, the average treatment delay was 7.2 years between the onset of initial symptoms and the initiation of treatment (SD = 9.3 years). The investigators found that a significant proportion of study participants had been on an anticonvulsant or were classified as having pseudostatus epilepticus, indicating that they had been misclassified as having a neurological disease and inappropriately treated, which contributed to the delay in effective treatment. The fact that specific patient factors did not appreciably shorten the delay to diagnosis, and that confounding factors did not appreciatively increase the delay, suggested that physician factors contributed mightily to the delayed treatment.33

Regarding functional motor disorders, an Italian retrospective pilot study identified an average delay of 6.63 years (SD = 8.57 years) between the onset of symptoms and the diagnosis. Eighty percent of patients were evaluated by an average of 3 physicians before receiving the correct diagnosis, and roughly three fourths (73%) of them had received 1 or more misdiagnoses of an organic neurological disease.34

What Does the Evaluation of FNDs Typically Entail?

The evaluation of FNDs proceeds much like that of the evaluation of any other neurological disease. The diagnosis rests upon taking a careful history (involving the creation of a timeline of symptoms, their progression, and fluctuations) and correlating these factors. Maintaining curiosity and empathy are important components of establishing rapport with individuals who have a probable FND diagnosis.35 A hypothesis-driven neurological examination is then conducted, with relative importance assigned to those findings associated with the symptoms that were elicited in the history, being mindful of pertinent positives and negatives. Throughout this process, the conditions considered in the differential diagnosis are assessed iteratively, and an evaluation strategy is created to refine the list. When physical findings are internally inconsistent (eg, there is a difference in symptom severity between history taking and examination, suggestibility) or incongruous with neurological disorders (eg, spread of tremor to another body part if the tremor is restrained [“Whack a Mole” sign], increased tone without cogwheel rigidity in parkinsonism), the diagnosis of a FND becomes more likely.26,36 Moreover, when a FND is suspected, clinicians should be cognizant of the possibility of overlapping symptoms, ie, symptoms that appear to be outside of what would be expected for 1 neurological problem may instead represent several overlapping neurological syndromes (eg, carpal tunnel syndrome and a C7 nerve root impingement).

The evaluation of a FND depends on the presenting symptoms, signs, and temporal sequencing. All diagnostic tools (eg, CT, MRI, and electrodiagnostic tests [eg, nerve conduction studies, electromyography, and electroencephalography]), as well as laboratory tests (including CSF analysis), may be conducted.

What Are the Obstacles to Diagnosis and Treatment?

The diagnosis and treatment of FND challenges patients, health care providers, and health care systems due to diagnostic dilemmas and challenging discussions with patients.

Making the diagnosis. FNDs are phenotypically heterogeneous (eg, headaches, balance issues, motor dysfunction, dizziness, perception problems, or seizures), have frequent comorbidities, and must be distinguished from other neurological or feigned illnesses (eg, factitious disorder, malingering). Comorbidities include identifiable neurological conditions or psychiatric disorders (eg, anxiety, depression, SSDs, dissociative disorders). In fact, having a neurological disorder may increase the risk of developing a FND.37 As a result, it may take years (seeing multiple providers and undergoing multiple tests) before a diagnosis of FND is made. Such testing is time-consuming for primary care providers and contributes to patient frustration and distrust in the medical system.

Communicating the diagnosis. Effective communication of the diagnosis of a FND is essential to patient engagement and treatment adherence. However, clinicians often struggle with this step due to their discomfort with the diagnosis, lack of knowledge about treatment options, and personal biases. A patient-centered approach in which a clinician explains the diagnostic process, acknowledges the role of psychological factors, and includes care partners in the conversation can help foster trust and improve patient buy in. Clinicians should avoid introducing psychiatry too early in the conversation, as this may alienate patients and reactivate feelings of abandonment or stigmatization. A clear, empathetic explanation of the diagnosis, emphasizing that FND is a legitimate medical condition, can alleviate these concerns.37

The patient’s understanding of the diagnosis. The patient’s acceptance of a FND diagnosis is closely linked to treatment outcomes.37 However, many patients misunderstand the diagnosis or feel stigmatized, which can interfere with their acceptance. Research shows that more than 81% of patients with a FND feel they have been treated poorly due to stigma that surrounds the illness.38 When patients learn that psychological factors may contribute to their symptoms, they may worry that their clinicians will stop treating them or believe they are feigning symptoms. The invisible nature of FND symptoms can also contribute to shame, as patients struggle without validation from family, friends, and health care providers.39

Referring to treatment. Effective treatment of FND requires a multidisciplinary approach that may be difficult to coordinate, particularly in busy health care settings. A shortage of providers with expertise in FND often leads to delays in diagnosis and treatment. Psychologists or therapists may address the psychological or cognitive components of FND, and allied health professionals (eg, physical therapists, occupational therapists, speech language pathologists) may address functional impairments.39 Some clinicians mistakenly believe that FND is untreatable, further delaying or complicating care. Successful management of FND requires collaboration among multiple specialists.

Who Should Treat Individuals Who Have a FND?

Given the high phenotypic variability of FNDs, treatment typically requires a multidisciplinary approach that is tailored to each patient.40 Evaluation and treatment often starts with referral to a neurologist who often acts as the team coordinator and identifies appropriate referrals for ongoing treatment.41 Since FNDs are frequently comorbid with psychiatric illnesses, referral to a psychiatrist is often indicated.42 Similarly, general medical comorbidities should be addressed by regular follow-up with primary care physicians or other medical subspecialists.

Patients with FNDs should also be treated by allied health professionals (eg, psychologists, psychotherapists, physical therapists, occupational therapists, speech therapists) to target specific symptoms (eg, gait and motor impairment, daily functioning, independence, swallowing).43–45 Psychologists and psychotherapists can employ cognitive-behavioral therapy (CBT) to mitigate functional symptoms and target underlying psychological factors, current beliefs, emotions, and behaviors that drive FNDs. In some parts of the country, patients may have access to FND clinics, which may help triage and facilitate well-coordinated access to treatment resources.

Where Should Individuals With a FND Be Treated?

Patients diagnosed with FNDs are often treated in a myriad of settings (eg, outpatient practices, specialty FND clinics, inpatient neurological or psychiatric units, and inpatient rehabilitation units). Most individuals with FNDs are treated as outpatients, although access to specialty treatment remains a challenge for many patients. Currently, criteria for when inpatient admission is recommended for the treatment of FND are lacking, although most patients present for assessment and treatment of acute symptoms or for chronic symptoms that contribute to disability and require intensive treatment.46 Fortunately, inpatient rehabilitation, with intensive physical therapy, reduces motor symptoms.47 Data on the benefit of care on inpatient psychiatric units are less clear.46 Ultimately, the appropriate setting for treatment hinges on illness severity, the need for more intensive evaluation, specific symptom constellations, functional impairment, and access to resources.

How Should Individuals With a FND Be Treated?

Treatment for FND begins with a thorough evaluation, validation of the patients’ experience, education about the etiology of symptom development, and the typical treatment course.48 Establishment of a strong therapeutic alliance during this evaluation facilitates engagement in treatment.49 After a diagnosis is made, further treatment will depend on the individual’s symptom burden, with many patients receiving referrals for physiotherapy and psychotherapy. For those with motor symptoms, physical therapy reduces symptoms and improves gait47; consensus recommendations for physiotherapy include education, alliance building, movement retraining, and individualized strategies for symptom management.42 Occupational therapy also promotes functional independence,44 while speech therapy is helpful for those presenting with difficulties in communication, impairment of the upper airway, and swallowing.45

Among the psychotherapies, CBT is the most-studied psychotherapeutic intervention for FND.50 Its use has been validated in the treatment of functional seizures as well as for a variety of FNDs.50 Other psychotherapies (including psychodynamic psychotherapy, third wave approaches [such as mindfulness], body centered therapy, dialectical-behavioral therapy, hypnosis, and group therapies) have all shown some benefit in FND treatment.51 In addition, prolonged exposure therapy may be useful for treatment of comorbid PTSD, with subsequent improvement in FND.51

Although pharmacotherapy is not currently indicated for the treatment of FNDs, such treatment may alleviate other conditions. However, individuals with FND may be more susceptible to medication side effects.50 Potential treatment options include transcranial magnetic stimulation,52 sedation,53 botulinum toxin,54 and biofeedback.55

Does the Military/VA Have Treatment Centers or Programs for FND? Do All Military Branches Have Similar Considerations?

There are no special treatment centers in the military of which the authors are aware. Each center creates a system based on the resources available to them. Some hospitals create a working group (of sorts) that meets monthly to discuss cases and coordinate care. The group typically includes neurology, clinical health psychology, a speech therapist, and the residents rotating on those services.

What Are the Sequelae of FNDs?

Preliminary data have identified that up to half of those with functional symptoms had their symptoms remit following their hospital discharge.56 However, some longer-term data have shown that more than three-fourths (83%) of patients reported persistent weakness and/or sensory symptoms after a median follow-up of 12.5 years (42 patients), and roughly one fourth (29%) took a medical retirement.57 Another study (with 107 patients and a 14-year follow-up) found that essentially half (49%) of patients failed to improve or had more severe symptoms, while one-fifth (20%) of those with a FND reported a full resolution of symptoms.58

Although meaningful associations have been identified between certain neurocircuits and the development of FNDs, the pathophysiology of FNDs remains unclear.59 Complicating our understanding of FNDs is that individuals with FNDs have a higher prevalence of comorbid psychiatric illnesses, including anxiety, depressive, and personality disorders,59,60 and that these conditions negatively correlate with quality of life.61 Positive outcomes have been linked with psychotherapy,62,63 multidisciplinary inpatient programs,64,65 and self-help manuals.66 Needless to say, treatment of FNDs is challenging for physicians and can be debilitating for patients.

Is There a Model of Illness to Provide Patients and Their Families a ClearUnderstanding of FND?

The framework for understanding FND is best represented by the biopsychosocial model due to the interactive complexity of the disorder. The older biomedical model of illness is deficient here, as it suggests every disease process can be solely explained in terms of a deviation from normal function, implicating infections, injuries, genes, or development processes.67

When faced with the unpredictability of a disorder like FND, patients and their families are frequently bewildered and overwhelmed. They should be made aware that there is an incomplete understanding of the etiology of the condition and that it will likely involve an interdisciplinary team for treatment. However, they can be encouraged that the illness is not degenerative, and all treatment is based on rehabilitation.

Multiple patient-facing sites abound on this baffling disorder; however, not all of them are medically sound. To direct patients to reputable sites, suggesting well respected academic centers is recommended. Massachusetts General Hospital recommends an additional site within their patient information on FND (https://neurosymptoms.org/en/),68 where a Scottish neurologist (who is considered an expert on the condition) states that FND is a “software” issue of the brain, not the “hardware” (as in stroke or MS). The neurologist goes on to explain the disorder in easy to understand, nonthreatening language, with an emphasis on wellness that should be reassuring to both patients and their families. Providing patients with respected resources is an important part of the therapeutic process and can highlight parallel journeys to wellness.

What Percent of Patients Diagnosed With a FND Receive a Medical, Neurological, or Psychiatric Diagnosis?

The percentage of patients initially diagnosed with FND who end up receiving a different medical, neurological, or psychiatric diagnosis differs from study to study. According to 1 frequently cited systematic review, the diagnostic reliability of FNDs is generally stable, with a low misdiagnosis rate (4%) after a mean of 5-year follow-up.69 Another study found more than 5 times as many erroneous FND diagnoses, with 20% of 212 patients initially diagnosed with FND later found to have alternative diagnoses.70 In contrast, only 0.4% of 2,637 patients initially diagnosed with a neurological condition were found to have a functional diagnosis upon follow up.71 The discrepancy between inaccurate psychiatric diagnoses and inaccurate neurological diagnoses demonstrates the importance of ruling out possible medical etiologies before diagnosing a patient with FND, as psychiatric diagnoses are rarely overturned and can pose a barrier to subsequent medical diagnosis.

Do FNDs Qualify as a Cause of Disability?

Unfortunately, there are more questions than answers regarding how to assess disability in those with FND. Since the neurophysiology of FNDs remains unclear, concise policies and regulations regarding disability associated with FNDs are lacking in the United States. In the civilian sector, state laws vary widely regarding the specified physical limitations (eg, driving) of FNDs or eligible benefits for applicants. In cases involving PNES, state laws provide little guidance and tend to defer to physicians’ recommendations regarding driving restrictions. This can result in economic hardships for some individuals. For those individuals with FND who are granted disability income, this decision may depend on proving that there is an inability to work. Numerous online blogs and YouTube channels function as support networks and sources of unofficial information sharing. Often, they recommend hiring an attorney who specializes in disability cases to minimize chances of a claim being denied.

Based on a review of eligibility requirements for supplemental security income from the Social Security Administration website,72 FND could meet requirements for eligibility for SSI, though is currently listed under qualifying mental health diagnoses as conversion disorder rather than FND. To meet requirements, the disorder must meet both criterion A and B. Criterion A requires medical documentation of symptoms consistent with FND, not better explained by another medication condition or mental disorder. Criterion B requires extreme limitation in 1 or marked limitation in 2 categories of mental functioning including (1) understanding, remembering, or applying information; (2) interacting with others; (3) concentrating, persisting, or maintaining pace; and (4) adapting or managing oneself.

Do FNDs Qualify as a Cause for Service Connected Disability?

Although some service members have been medically separated from military service due to FND as was the case of Mr A, decisions about military separation, medical retirement, or service-connected disability status are established on a case-by-case basis. Like the civilian sector, specific recommendations regarding those with FND are lacking in the Department of Defense Instruction for Medical Standards for Military Service: Retention.73 For a medical or psychiatric condition to be awarded a service connection, the patient’s current disability must be linked to an incident in the military that either caused or worsened the condition. Service-connected disabilities are assigned a severity rating by the Veterans Affairs (VA), determining the VA disability compensation a veteran will receive.74

With the percentage of veterans receiving a service-connected disability rating rising to 31% in 2022,75 there is increasing awareness of conditions that are considered eligible. Of the nearly 300 diagnoses listed in the DSM-5, the VA considers only 31 mental health disorders to be eligible for service-connected disability compensation. Significantly, FND is 1 of them, listed under the diagnostic code 9424 and carrying the description “Conversion Disorder/Functional Neurological Disorder.”76 With PTSD being the most-diagnosed and highest-compensated mental health condition in the veteran population,77 it is not surprising that FND compensation would accompany this diagnosis, either during or after military service. In addition, some veterans who have been diagnosed with service connected FND have also been awarded additional benefits for secondary psychiatric symptoms that have resulted from this diagnosis, such as anxiety and depression.78

What Happened to Mr A?

A diagnosis of a FND was made based on his presentation and the exclusion of overlapping syndromes. The pattern of neurological findings on examination, supported by the history, was incongruent with established neurological conditions and neurological anatomy and physiology. For example, the finding of normal reflexes in the setting of paraparesis was inconsistent with a spinal cord or nerve root localization in which one would expect hyperreflexia or hyporeflexia, respectively. Recognizing that clinical examinations may not be textbook in nature and that patients can have more than 1 disease at a time (ie, Hickam’s dictum),79 evaluation for overlapping syndromes was undertaken and found to be unrevealing. Mr A was referred to a health psychologist for individual therapy and to the FND/somatic symptom support group at our institution. Unfortunately, he made little physical progress, and he left active-duty service approximately 18 months later. By the time of his military discharge, he used a walker rather than a wheelchair.

CONCLUSION

FNDs are conditions in which the primary pathophysiologic processes involve alterations in the function of brain networks rather than abnormalities of brain structures; they are clinical syndromes with alterations in motor, sensory, or cognitive performance that are distressing or impairing and that manifest variable performance within and between tasks. Although the pathophysiology of FNDs remains unclear, the most common presentations of FND are functional seizures (also called dissociative or PNES) and functional movement disorders, including paresis.

FNDs are commonly comorbid with depression, anxiety, traumatic stress disorders, and cluster B personality traits; however, they also coexist with other functional somatic disorders, including chronic pain and irritable bowel syndrome. Individuals with FNDs are less likely to believe that “stress or worry” might be causing their symptoms, than are those in control populations. For a medical or psychiatric condition to be awarded a service connection and disability compensation, the patient’s current disability must be linked to an incident in the military that either caused or worsened the condition; significantly, FND is one of these conditions.

Article Information

Published Online: July 24, 2025. https://doi.org/10.4088/PCC.25f03928

© 2025 Physicians Postgraduate Press, Inc.

Submitted: January 27, 2025; accepted May 5, 2025.

To Cite: Rustad JK, Hodges S, DeSimone A, et al. Functional neurological disorders in active-duty military personnel and veterans: challenges to diagnosis and treatment. Prim Care Companion CNS Disord 2025;27(4):25f03928.

Author Affiliations: Geisel School of Medicine at Dartmouth, Lebanon, New Hampshire (Rustad); Larner College of Medicine at University of Vermont, Burlington, Vermont (Rustad, Andrews); Burlington Lakeside VA Community Based Outpatient Clinic, Burlington, Vermont (Rustad); White River Junction VA Medical Center, White River Junction, Vermont (Rustad); Naval Medical Readiness Training Command, San Diego, California (Hodges); Uniformed Services University, Bethesda, Maryland (Hodges); Bayhealth Medical Center, Dover, Delaware (DeSimone); Philadelphia College of Osteopathic Medicine, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania (DeSimone); Walter Reed National Military Medical Center, Bethesda, Maryland (Ford); Harry S Truman Veteran’s Hospital, Columbia, Missouri (Boone); University of Missouri Medical School, Columbia, Missouri (Ford); Wright State Boonshoft School of Medicine, Dayton, Ohio (Weber, Bernal); Wright Patterson AFB, Dayton, Ohio (Weber, Bernal); University of Vermont Medical Center in Burlington, Burlington, Vermont (Andrews); University Hospitals–Cleveland Medical Center/Case Western Reserve University, Cleveland, Ohio (Santoy); Department of Psychiatry, Massachusetts General Hospital/Harvard Medical School, Boston, Massachusetts (Stern).

Corresponding Author: James K. Rustad, MD, Department of Psychiatry, Geisel School of Medicine at Dartmouth, Dartmouth-Hitchcock Medical Center, One Medical Center Dr, Lebanon, NH 03756 ([email protected]).

Relevant Financial Relationships: Dr Rustad is employed by the US Department of Veterans Affairs, but the opinions expressed in this presentation do not reflect those of the Department of Veterans Affairs. Dr Hodges: “The views expressed in this article reflect the results of research conducted by the author and do not necessarily reflect the official policy or position of the Department of the Navy, Department of Defense, nor the United States Government.” Dr Boone is employed at the US Department of Veteran’s Affairs, but the views expressed are only reflective of her own. Drs DeSimone, Andrews, and Santoy have no disclosures to report. Drs Weber and Bernal: “The views expressed in this article reflect the results of research conducted by the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the official policy or position of the United States Air Force, Department of Defense, nor the United States Government.” Dr Stern has received royalties from Elsevier for editing textbooks on psychiatry.

Funding/Support: None.

Clinical Points

- The most common presentations of functional neurological disorder (FND) are functional seizures (also called dissociative or psychogenic nonepileptic seizures) and functional movement disorders, including paresis. Other common manifestations are somatosensory or visual symptoms and speech disorders. However, when physical findings are internally inconsistent or incongruous with neurological disorders, the diagnosis of FND becomes more likely.

- Patient-centered studies have repeatedly demonstrated that patients do not attribute their symptoms to psychosocial or psychological factors.

- The diagnosis of FND rests upon taking a careful history (involving the creation of a timeline of symptoms, their progression, and fluctuations), and correlating these factors.

- Treatment of FNDs is often challenging for physicians and debilitating for patients.

References (79)

- Smakowski AL, Hüsing P, Völcker S, et al. Psychological risk factors of somatic symptom disorder: a systematic review and meta-analysis of cross-sectional and longitudinal studies. J Psychosom Res. 2024;181:111608. PubMed

- Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders: DSM-5-TR. Fifth Edition, Text Revision. American Psychiatric Association Publishing; 2022: 1050.

- Dunphy L, Penna M, Jihene EK. Somatic symptom disorder: a diagnostic dilemma. BMJ Case Rep CP. 2019;12(11):e231550.

- Hallett M, Aybek S, Dworetzky BA, et al. Functional neurological disorder: new subtypes and shared mechanisms. Lancet Neurol. 2022;21(6):537–550. Erratum in: Lancet Neurol. 2022;21(6):e6. PubMed CrossRef

- Harris SR. Psychogenic movement disorders in children and adolescents: an update. Eur J Pediatr. 2019;178(4):581–585. PubMed CrossRef

- Chouksey A, Pandey S. Functional movement disorders in elderly. Tremor Other Hyperkinetic Movements. 2019;9:1–6.

- Baizabal-Carvallo JF, Jankovic J. Gender differences in functional movement disorders. Mov Disord Clin Pract. 2020;7(2):182–187. PubMed CrossRef

- Goldstein LH, Robinson EJ, Reuber M, et al. Characteristics of 698 patients with dissociative seizures: a UK multicenter study. Epilepsia. 2019;60(11):2182–2193. PubMed CrossRef

- Ludwig L, Pasman JA, Nicholson T, et al. Stressful life events and maltreatment in conversion (functional neurological) disorder: systematic review and meta-analysis of case-control studies. Lancet Psychiatry. 2018;5(4):307–320. PubMed CrossRef

- Kletenik I, Sillau SH, Isfahani SA, et al. Gender as a risk factor for functional movement disorders: the role of sexual abuse. Mov Disord Clin Pract. 2020;7(2):177–181. PubMed CrossRef

- Watson C, Sivaswamy L, Agarwal R, et al. Functional neurologic symptom disorder in children: clinical features, diagnostic investigations, and outcomes at a tertiary care children’s hospital. J Child Neurol. 2019;34(6):325–331. PubMed CrossRef

- Brown RJ, Reuber M. Psychological and psychiatric aspects of psychogenic nonepileptic seizures (PNES): a systematic review. Clin Psychol Rev. 2016;45:157–182. PubMed CrossRef

- Kranick S, Ekanayake V, Martinez V, et al. Psychopathology and psychogenic movement disorders. Mov Disord. 2011;26(10):1844–1850. PubMed CrossRef

- Frucht L, Perez DL, Callahan J, et al. Functional dystonia: differentiation from primary dystonia and multidisciplinary treatments. Front Neurol. 2021;11:605262.

- Tinazzi M, Geroin C, Erro R, et al. Functional motor disorders associated with other neurological diseases: beyond the boundaries of “organic” neurology. Eur J Neurol. 2021;28(5):1752–1758. PubMed CrossRef

- Tinazzi M, Morgante F, Marcuzzo E, et al. Clinical correlates of functional motor disorders: an Italian multicenter study. Mov Disord Clin Pract. 2020;7(8):920–929. PubMed CrossRef

- Věchetová G, Slovák M, Kemlink D, et al. The impact of non-motor symptoms on the health related quality of life in patients with functional movement disorders. J Psychosom Res. 2018;115:32–37.

- Jones B, Reuber M, Norman P. Correlates of health-related quality of life in adults with psychogenic nonepileptic seizures: a systematic review. Epilepsia. 2016;57(2):171–181. PubMed CrossRef

- Garrett AR, Hodges SD, Stahlman S. Epidemiology of functional neurological disorder, active component, U.S. Armed Forces, 2000-2018. MSMR. 2020;27(7):16–22. PubMed

- Weinstein EA. Conversion disorders. In: Zajtchuk R, Bellamy RF, eds. Textbook of Military Medicine: War Psychiatry. Office of the Surgeon General; 1995:383–407.

- Trimble M, Reynolds EH. A brief history of hysteria: from the ancient to the modern. Handb Clin Neurol. 2016;139:3–10. PubMed CrossRef

- Barnes JK. The Medical and Surgical History of the War of the Rebellion (1861- 1865). Government Printing Office; 1870.

- Bailey P, Haber R. Occurrence of neuropsychiatric disease in the Army. In: The Medical Department of United States Army in the World War. U.S. Government Printing Office; 1929;10:154.Neuropsychiatry

- Babinski JHF, Froment J. Hysteria or Pithiatism and Reflex Nervous Disorders in the Neurology of War. University of London Press; 1918.

- Ludwig L, Pasman JA, Nicholson T, et al. Stressful life events and maltreatment in conversion (functional neurological) disorder: systematic review and meta-analysis of case-control studies. Lancet Psychiatry, 2018;5(4):307–320. PubMed CrossRef

- Espay AJ, Aybek S, Carson A, et al. Current concepts in diagnosis and treatment of functional neurological disorders. JAMA Neurol. 2018;75(9):1132–1141. PubMed CrossRef

- Cock HR, Edwards MJ. Functional neurological disorders: acute presentations and management. Clin Med. 2018;18(5):414–417. PubMed CrossRef

- Lidstone SC, Costa-Parke M, Robinson EJ, et al. Functional movement disorder gender, age and phenotype study: a systematic review and individual patient meta-analysis of 4905 cases. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2022;93(6):609–616. PubMed CrossRef

- Perez DL, Keshavan MS, Scharf JM, et al. Bridging the great divide: what can neurology learn from psychiatry? J Neuropsychiatry Clin Neurosci. 2018;30(4):271–278. PubMed CrossRef

- Stone J, Warlow C, Sharpe M. The symptom of functional weakness: a controlled study of 107 patients. Brain. 2010;133(Pt 5):1537–1551. PubMed CrossRef

- Stone J, Binzer M, Sharpe M. Illness beliefs and locus of control: a comparison of patients with pseudoseizures and epilepsy. J Psychosom Res. 2004;57(6):541–547. PubMed CrossRef

- Ludwig L, Whitehead K, Sharpe M, et al. Differences in illness perceptions between patients with non-epileptic seizures and functional limb weakness. J Psychosom Res. 2015;79(3):246–249. PubMed CrossRef

- Reuber M, Fernández G, Bauer J, et al. Diagnostic delay in psychogenic nonepileptic seizures. Neurology. 2002;58(3):493–495. PubMed CrossRef

- Tinazzi M, Gandolfi M, Landi S, et al. Economic costs of delayed diagnosis of functional motor disorders: preliminary results from a cohort of patients of a specialized clinic. Front Neurol. 2021;12:786126. PubMed CrossRef

- Stone J, Carson A, Hallett M. Functional neurological disorders: the neurological assessment as treatment. Pract Neurol. 2016;16(1):7–17.

- Perez DL, Aybek S, Popkirov S, et al. A review and expert opinion on the neuropsychiatric assessment of motor functional neurological disorders. J Neuropsychiatry Clin Neurosci. 2021;33(1):14–26. PubMed CrossRef

- O’Neal MA, Dworetzky BA, Baslet G. Functional neurological disorder: engaging patients in treatment. Epilepsy Behav Rep. 2021;16:100499. PubMed

- McLoughlin C, McGhie-Fraser B, Carson A, et al. How stigma unfolds for patients with functional neurological disorder. J Psychosom Res. 2024;181:111667. PubMed CrossRef

- Mavroudis I, Kazis D, Kamal FZ, et al. Understanding functional neurological disorder: recent insights and diagnostic challenges. Int J Mol Sci. 2024;25(8):4470. PubMed CrossRef

- Gilmour GS, Nielsen G, Teodoro T, et al. Management of functional neurological disorder. J Neurol. 2020;267(7):2164–2172. PubMed CrossRef

- Stone J. Functional neurological disorders: the neurological assessment as treatment. Pract Neurol. 2016;16(1):7–17. PubMed CrossRef

- Nielsen G, Stone J, Matthews A, et al. Physiotherapy for functional motor disorders: a consensus recommendation. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2015;86(10):1113–1119. PubMed CrossRef

- O’Neal MA, Baslet G. Treatment for patients with a functional neurological disorder (conversion disorder): an integrated approach. Am J Psychiatry. 2018;175(4):307–314. PubMed CrossRef

- Nicholson C, Edwards MJ, Carson AJ, et al. Occupational therapy consensus recommendations for functional neurological disorder. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2020;91(10):1037–1045. PubMed CrossRef

- Baker J, Barnett C, Cavalli L, et al. Management of functional communication, swallowing, cough and related disorders: consensus recommendations for speech and language therapy. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2021;92(10):1112–1125. PubMed CrossRef

- Gilmour GS, Jenkins JD. Inpatient treatment of functional neurological disorder: a scoping review. Can J Neurol Sci. 2021;48(2):204–217. PubMed CrossRef

- Jordbru AA, Smedstad LM, Klungsøyr O, et al. Psychogenic gait disorder: a randomized controlled trial of physical rehabilitation with one-year follow-up. J Rehabil Med. 2014;46(2):181–187. PubMed CrossRef

- FND Treatment. Accessed January 24, 2025. https://fndhope.org/fnd-guide/treatment/

- Stone J, Carson A, Hallett M. Explanation as treatment for functional neurologic disorders. Handb Clin Neurol. 2016;139:543–553. PubMed CrossRef

- Stone J, Edwards M. Trick or treat? Showing patients with functional (psychogenic) motor symptoms their physical signs. Neurology. 2012;79(3):282–284. PubMed CrossRef

- Finkelstein SA, Adams C, Tuttle M, et al. Neuropsychiatric treatment approaches for functional neurological disorder: a how to guide. Semin Neurol. 2022;42(2):204–224. PubMed CrossRef

- Myers L, Sarudiansky M, Korman G, et al. Using evidence-based psychotherapy to tailor treatment for patients with functional neurological disorders. Epilepsy Behav Rep. 2021;16:100478. PubMed CrossRef

- Oriuwa C, Mollica A, Feinstein A, et al. Neuromodulation for the treatment of functional neurological disorder and somatic symptom disorder: a systematic review. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2022;93(3):280–290. PubMed CrossRef

- Nicholson TRJ, Voon V. Transcranial magnetic stimulation and sedation as treatment for functional neurologic disorders. Handb Clin Neurol. 2016;139:619–629. PubMed CrossRef

- Vizcarra JA, Lopez-Castellanos JR, Dwivedi AK, et al. OnabotulinumtoxinA and cognitive behavioral therapy in functional dystonia: a pilot randomized clinical trial. Parkinsonism Relat Disord. 2019;63:174–178. PubMed CrossRef

- Espay AJ, Edwards MJ, Oggioni GD, et al. Tremor retrainment as therapeutic strategy in psychogenic (functional) tremor. Parkinsonism Relat Disord. 2014;20(6):647–650. PubMed CrossRef

- Folks DG, Ford CV, Regan WM. Conversion symptoms in a general hospital. Psychosomatics. 1984;25(4):285–295. PubMed CrossRef

- Stone J, Sharpe M, Rothwell PM, et al. The 12-year prognosis of unilateral functional weakness and sensory disturbance. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2003;74(5):591–596. PubMed CrossRef

- Gelauff JM, Carson A, Ludwig L, et al. The prognosis of functional limb weakness: a 14-year case-control study. Brain. 2019;142(7):2137–2148. PubMed CrossRef

- Baizabal-Carvallo JF, Hallett M, Jankovic J. Pathogenesis and pathophysiology of functional (psychogenic) movement disorders. Neurobiol Dis. 2019;127:32–44. PubMed CrossRef

- Defazio G, Pastore A, Pellicciari R, et al. Personality disorders and somatization in functional and organic movement disorders. Psychiatry Res. 2017;257:227–229. PubMed CrossRef

- Věchetová G, Slovák M, Kemlink D, et al. The impact of non-motor symptoms on the health-related quality of life in patients with functional movement disorders. J Psychosom Res. 2018;115:32–37.

- Carlson P, Nicholson Perry K. Psychological interventions for psychogenic non-epileptic seizures: a meta-analysis. Seizure. 2017;45:142–150. PubMed CrossRef

- Gaskell C, Power N, Novakova B, et al. A meta-analytic review of the effectiveness of psychological treatment of functional/dissociative seizures on non-seizure outcomes in adults. Epilepsia. 2023;64(7):1722–1738. PubMed CrossRef

- Hebert C, Behel JM, Pal G, et al. Multidisciplinary inpatient rehabilitation for functional movement disorders: a prospective study with long term follow up. Parkinsonism Relat Disord. 2021;82:50–55. PubMed CrossRef

- Saifee TA, Kassavetis P, Pareés I, et al. Inpatient treatment of functional motor symptoms: a long-term follow-up study. J Neurol. 2012;259(9):1958–1963. PubMed CrossRef

- Wade DT, Halligan PW. Do biomedical models of illness make for good healthcare systems? BMJ Clin Res ed. 2004;329(7479):1398–1401. PubMed CrossRef

- Stone J. Functional Neurological Disorder. FND Guide; 2025. https://neurosymptoms.org/en/

- Sharpe M, Walker J, Williams C, et al. Guided self-help for functional (psychogenic) symptoms: a randomized controlled efficacy trial. Neurology. 2011;77(6):564–572. PubMed CrossRef

- Stone J, Smyth R, Carson A, et al. Systematic review of misdiagnosis of conversion symptoms and “hysteria”. BMJ. 2005;331(7523):989. PubMed CrossRef

- Williams S, Southall C, Haley S, et al. To the emergency room and back again: circular healthcare pathways for acute functional neurological disorders. J Neurol Sci. 2022;437:120251. PubMed CrossRef

- Disability Evaluation Under Social Security: 12.00 Mental Disorders – Adult. Accessed April 25, 2025. https://www.ssa.gov/disability/professionals/bluebook/12.00-MentalDisorders-Adult.htm#12_07

- DoD Instruction on Medical Standards and Retention. Accessed January 24, 2025. https://www.esd.whs.mil/Portals/54/Documents/DD/issuances/dodi/613003_vol02.PDF

- Walzl D, Carson AJ, Stone J. The misdiagnosis of functional disorders as other neurological conditions. J Neurol. 2019;266(8):2018–2026. PubMed CrossRef

- US Department of Veteran’s Affairs. Eligibility for VA Disability Benefits. 2023. Accessed January 24, 2025. https://www.va.gov/disability/eligibility/

- Census Bureau. S2101 Veteran Status. 2023 ACS 1 Year Subject Tables. 2023. Accessed January 24, 2025. https://www.data.census.gov/table/ACSST1Y2023.S2101?q=Veterans

- Code of Federal Regulations: Title 38 - Pensions, Bonuses, and Veterans’ Relief. Chapter I - Department of Veterans Affairs. Part 4 - Schedule for Rating Disabilities. Subpart B - Disability Ratings. Mental Disorders. Section 4.130 Schedule of ratings - Mental Disorders. Accessed January 24, 2025. https://www.ecfr.gov/current/title-38/chapter-I/part-4/subpart-B/subject-group-ECFRfa64377db09ae97/section-4.130

- Appeal from the Department of Veterans Affairs Regional Office in Portland, Oregon. Accessed May 12, 2014. https://www.va.gov/vetapp14/Files7/1453659.txt

- Heckmann JG, White M, Ernst S. Images of the month: unexpected neurological comorbidity: Occam’s razor or Hickam’s dictum? Clin Med. 2020;20(3):e22–e23.

Enjoy this premium PDF as part of your membership benefits!