Abstract

Objective: To identify differences in the impact of COVID-19 on mental health in middle-aged and older adults in India.

Methods: An online web-based cross- sectional study was carried out in 8 countries during the COVID-19 pandemic. The current study analyzed data from India (the survey was conducted between July 2020 and September 2020). The selection criteria were having internet access, residing in India, and age at least 35 years. Participants aged ≥55 years were categorized as older adults and those aged 35–54 years as middle aged. Data were collected using a structured questionnaire and the Patient Health Questionnaire-9, Generalized Anxiety Disorder Scale-7, and Loneliness Scale.

Results: The final analysis included 181 older adults and 321 middle-aged adults. There was a higher prevalence of depression and anxiety disorder among middle-aged adults compared to older adults. The difference was significant for depression (χ2=15.09, P<.001), but not for anxiety disorder. Logistic regression analysis found that after adjustment for sociodemographic and psychosocial variables, the presence of either depression or anxiety was significantly associated with age, perception of knowledge of COVID-19, lack of companion, feeling isolated, and feeling left out.

Conclusion: Older adults were found to have less depression and anxiety disorder compared to middle-aged adults. Loneliness and perception of knowledge about COVID-19 can affect the association between the presence of mental illness and age.

Prim Care Companion CNS Disord 2025;27(5):25m03963

Author affiliations are listed at the end of this article.

The COVID-19 pandemic and associated restrictions affected millions of people around the world both physically and mentally. While the pandemic led to an overall increase in the prevalence of common mental disorders,1 the prevalence rates varied widely across the different countries.2 The available studies also found a differential effect of age on the prevalence of mental health problems secondary to the pandemic,3,4 with the younger population being affected more than older adults.5

Middle-aged and older adults have different stressors compared to the younger population. Middle-aged adults are often at a critical juncture in their lives. This stage is characterized by balancing multiple roles and responsibilities, including career demands, caregiving for children and aging parents, and managing their own health and well-being.6 The pandemic disrupted these roles, leading to heightened stress, anxiety, and depression. Economic instability and job insecurity further compounded these mental health challenges, as many middle-aged adults had to face pay cuts, job losses, or the pressure of maintaining productivity while working from home. Additionally, the dual burden of caring for both younger and older family members during a health crisis placed an extraordinary strain on this age group.

In contrast, older adults faced a different set of challenges during the pandemic. This group was inherently more vulnerable to severe illness from COVID-19 due to age-related health conditions and a potentially weakened immune system.

Consequently, older adults experienced greater fear and anxiety regarding their physical health. The pandemic exacerbated social isolation among many elderly individuals, increasing their feelings of loneliness and depression.

The cessation of routine social interactions and activities deprived many older adults of essential support systems and coping mechanisms.

Moreover, the digital divide posed significant barriers for older adults in accessing tele-health services and staying connected with loved ones, further intensifying their sense of isolation.

Due to differences in stressors, it is expected that the impact of COVID-19 on the mental health of older and middle-aged adults would also have been different. Despite the growing body of research on COVID-19’s impact on mental health, there remains a paucity of studies focusing specifically on the comparative mental health outcomes of middle-aged and older adults.

This study seeks to fill this gap by conducting a cross- sectional, comparative analysis of the mental health impacts of COVID-19 on middle-aged and older adults in India. By identifying the mental health challenges faced by these age groups and various associated sociodemographic and clinical factors, the study aims to provide a nuanced understanding of how the pandemic has affected their psychological well-being. Such an understanding is crucial for developing targeted mental health interventions and support strategies that cater to the specific needs of these populations.

METHODS

Study Design

The current analysis was part of an online web-based cross-sectional study carried out among adults in 8 countries during the first wave of the COVID-19 pandemic. The methodology has been described in previous publications.7,8 The link for the study questionnaire was sent through social media apps like WhatsApp using the snowball technique. The survey was conducted between July 2020 and September 2020 in India after obtaining ethical clearance from the institutional ethics committee. All participants were given the contact details of the investigators to obtain help related to mental health care.

Sample

The sample (N=502) for this study was drawn from the respondents who had participated in the first wave of the survey. The inclusion criteria for both the middle-aged and older adults were as follows: had internet access, were residing in India, were able to understand the questions, and were willing to participate in the study. For the older adult group, respondents who reported age ≥55 years were included, while respondents aged between 35 and 54 years were included in the middle-aged adult group.

Tools

A semistructured questionnaire specially developed for the study was used to assess the sociodemographic data, presence of preexisting mental illness, perception of knowledge related to COVID-19, and impact of COVID-19 on relations with friends and family. The Patient Health Questionnaire-9 (PHQ-9) and Generalized Anxiety Disorder Scale-7 (GAD-7) were applied to screen for depression and anxiety, respectively. The PHQ-9 is a self-administered tool to screen for depression and its severity. The scale has a sensitivity and specificity of 88% and 88%, respectively, has a good internal reliability with a Cronbach α of 0.89, and has excellent test-retest reliability.9 The GAD-7 is a 7-item tool used to screen for anxiety disorder and its severity. The scale has a sensitivity and specificity of 89% and 82%, respectively, has excellent internal consistency with a Cronbach α of 0.92, and has good test-retest reliability (intraclass correlation of 0.83).10 The Loneliness Scale is a 3-item scale used to measure loneliness and has good internal consistency with a Cronbach α of 0.82.11

Statistical Analysis

SPSS version 20.0 was used for statistical analysis. Categorical data were summarized using frequencies and percentages. Chi-square test was used to find any significant difference between the middle-aged and older adult populations with respect to various clinical and sociodemographic variables. Binomial logistic regression was conducted to find associations between presence of depression or anxiety (based on the PHQ-9 and GAD-7) and sociodemographic and clinical variables. A P value <.05 was considered significant for all tests.

RESULTS

A total of 181 older adults (aged ≥55 years) and 321 middle-aged adults (aged 35–54 years) were included in the study.

Sociodemographics

The sample had significantly more females in the middle-aged adult group (n=214, 66.7%) compared to the older adult group (n=94, 51.9%) (X2 =10.6, P =.001). Also, significantly more older adults (n=161, 89%) stayed in their own home or parents’ home compared to the middle-aged adults (n=229, 71.3%) (X2 =20.71, P <.001). There was no significant difference between the 2 groups with respect to religion, education, or current employment status. Children stayed significantly more with the middle-aged adults (n =157, 48.9%) than with the older adults (n=48, 26.5%) (X2 = 24.02, P <.001). Other older adults stayed significantly more with the older-aged adults (n=81, 48.8%) than with the middle-aged adults (n=102, 31.8%) (X2 =8.14, P =.004). Also, the number of people staying with participants was significantly higher among middle- aged adults compared to older adults: 45.3% (n=82) of older adults had 4 or more persons staying with them, while 59.5% (n =191) of middle-aged adults had 4 or more persons staying with them (X2 =9.40, P=.003).

COVID-19–Related Details

There was no significant difference between the middle-aged and older adults with respect to perception of knowledge of symptoms of COVID-19 (X2 =0.64, P =.43) and perception of knowledge of treatment of COVID-19 (X2 =0.10, P=.78). There was also no significant difference between the two groups with respect to providing care for others: 75 older adults (41.4%) provided care for others, while 151 middle-aged adults (47.0%) provided care for others at the time of the study.

Preexisting Mental Illness

A significantly greater number of middle-aged adults (n =43, 13.4%) compared to older adults (n=11, 6.1%) reported a preexisting mental health disorder before the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic (X2 =6.56, P=.02).

Impact of COVID-19 on Relationships with Friends and Family

There was no significant difference between the older and middle-aged adults with respect to the feeling of isolation from friends and family (X2 =1.45, P =.27), feeling closer to friends and family (X2 =2.50, P =.12), having more arguments (X2 =0.01, P =1.00), and talking more with friends and family (X2 =2.50, P=.12).

Loneliness

The current study found no difference between the older adult and middle-aged adult groups on any of the items on the Loneliness Scale, namely, lack of companion (X2 =3.03, P =.22), feeling left out (X2 =2.78, P =.25), and feeling isolated (X2 =1.73, P=.11).

Mental Illness

There was a higher prevalence of depression among the middle-aged adults (n=98, 30.5%) compared to older adults (n=27, 14.9%) based on the PHQ-9 screening, and the difference was significant (X2 =15.09, P <.001). Anxiety disorder was also found to be higher among middle-aged adults (n=67, 20.9%) compared to older adults (n=27, 14.9%). However, the difference was not significant (X2 =2.697, P=.121).

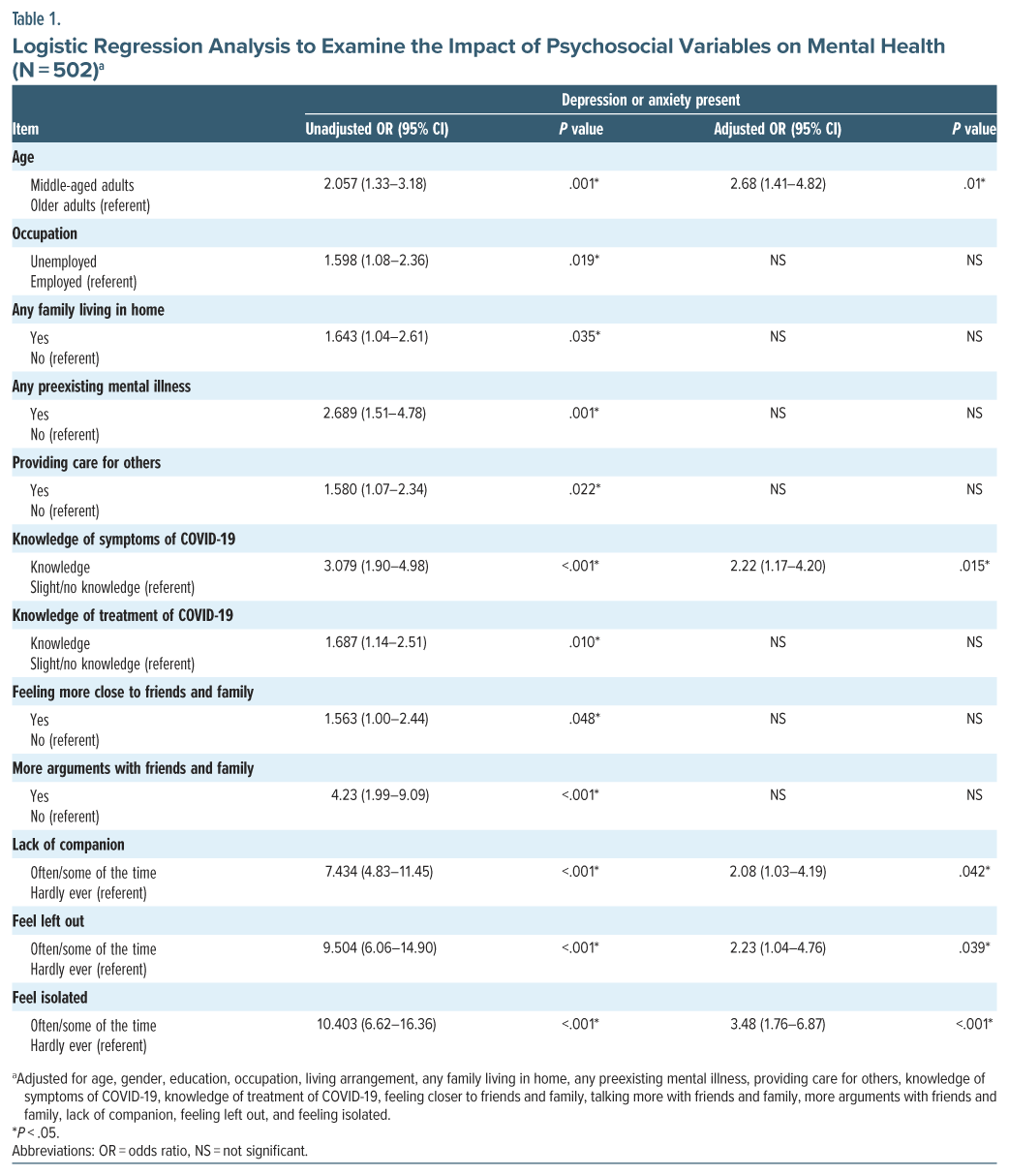

Association Between the Presence of Depression or Anxiety and Sociodemographic and Clinical Variables

On logistic regression analysis (Table 1), the variables found to be significantly associated with the presence of depression or anxiety were age, occupation, any family member living at home, presence of any preexisting mental illness, providing care for others, perception of being knowledgeable about symptoms of COVID-19, perception of being knowledgeable about treatment of COVID-19, feeling more close to family, talking more with friends and family, more arguments with family, lack of companion, feeling isolated, and feeling left out (adjusted R square= 0.416, which indicated that around 42% of variance in the presence of depression or anxiety can be explained by the included variables).

However, after adjustment for the various sociodemographic and psychosocial variables, it was found that only age, perception of knowledge of symptoms of COVID-19, lack of companion, feeling isolated, and feeling left out remained significantly associated with the presence of depression or anxiety.

DISCUSSION

The current study compared the impact of COVID-19 on the mental health of middle-aged and older adults in India during the COVID-19 pandemic and associated lockdown. The study found a significantly higher prevalence of depression among the middle-aged adults compared to the older adults, which remained significant even after adjustment for other sociodemographic and psychosocial variables. This finding is consistent with previous research from other countries,5 suggesting that middle-aged adults may bear a disproportionate psychosocial burden during stressful situations. For example, they have to balance caring for elderly family members and helping their children in their studies and careers while maintaining their own jobs.6

The COVID-19 pandemic resulted in widespread job disruptions, including layoffs, furloughs, and reduced work hours. These employment challenges likely played a significant role in elevating stress levels and contributing to an increase in mental health issues in this age group. The uncertainty surrounding income, job security, and future prospects may have created a pervasive sense of anxiety and psychological strain.

In contrast, older adults may have developed good coping strategies over time, contributing to greater emotional resilience to life situations. Previous research also has found that older adults have less stress reactivity, are resilient to life situations, and are less affected by stressful events.12 This could have contributed to the better mental health outcomes among older adults.

Interestingly, no significant difference was found in the reported loneliness between the 2 age groups, which contrasts with previous studies suggesting that loneliness is more common among the younger population compared to older adults.13 Cultural context may play a crucial role in this discrepancy in India compared to western literature—strong intergenerational family structures common in many parts of India may have protected both age groups from experiencing social isolation. Additionally, given that the current study was conducted online, only those adults with relatively good digital access and family support may have been included, potentially underrepresenting those who were more socially isolated. This is evident in that the reported prevalence of loneliness was lower in our study compared to other previous studies from India.14

Loneliness, when present, was found to be significantly associated with the presence of depression or anxiety, even after adjustment for the sociodemographic and psychosocial variables in both age groups. We also found that all 3 items of the Loneliness Scale—feeling isolated, lack of companionship, and feeling left out—were significantly associated with the presence of depression or anxiety. Many previous studies have also found loneliness to be a significant predictor for mental health disorders both before15 and during the COVID-19 pandemic.16 Also, studies have mentioned that loneliness increased during the pandemic due to the restrictions imposed by the government to prevent the spread of COVID-19 like physical distancing, restriction of movements, and requirement of people to stay at home.17

In our previous analysis of the data on older adults from the same sample, we found that older adults who reported higher social support had higher depressive and anxiety symptoms.18 In the current study, we found that feeling of being closer to the family and having more arguments with the family were significantly associated with the presence of depression or anxiety. However, after adjustment for the various psychosocial and demographic variables, these factors were not found to be significantly associated. This finding shows that when targeting interventions for enhancing social connectedness, it is necessary to focus on enhancing quality of social connections rather than quantity.

The study also has certain limitations. Since it was an online web-based survey, only those participants who had access to the internet could be contacted for the current study. Also, since categories were used to obtain information on age of the participants, we could not use the standard cutoff of age 60 years to define the elderly population. Despite these limitations, the current study contributes to the limited body of literature from India that compares the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on middle-aged and older adults. Moreover, since the study was conducted during the first wave of the pandemic, it provides an authentic snapshot of the mental health status prevalent at that time. The study also used standardized tools to assess depression, anxiety, and loneliness, which adds to the strengths of the study.

The implications of the study are substantial, highlighting the potential for developing strategies from a clinical and public health perspective to prevent mental health problems among older adults during pandemic-like situations. Despite improved technology, recent times have seen the emergence of challenging pandemics, and the current findings emphasize the core point: the elements of compassion, empathy, and connectedness are crucial toward the prevention of mental health issues. All adult patients in pandemic-like conditions should be routinely examined for depression and anxiety. It is pertinent to not only examine clinical and subclinical depressive features but also the individual’s family and social context for psychosocial management; thus, nonpharmacologic management is important from a prevention, early identification, and intervention standpoint in addition to pharmacologic treatment. People with preexisting mental illness should be regularly screened during pandemic-type conditions. Enhancing social connectedness through various means will act as a protective strategy to reduce the risk of depression and anxiety. Middle-aged adults, especially if working, need to be assessed for mental health issues.

Working adults should be equipped with stress management techniques and problem-solving skills not only from an occupational productivity perspective but also to enable them to resolve their personal issues. In the Indian context, psychologists are not part of the industrial organizations. One of the easier ways to help working adults would be to have trained professionals at the workplace who can address their psychological issues such as conflict, stress, or subclinical depression. Development of structured, community-based activities may also help to enhance social connectedness among people.

Article Information

Published Online: September 11, 2025. https://doi.org/10.4088/PCC.25m03963

© 2025 Physicians Postgraduate Press, Inc.

Submitted: March 11, 2025; accepted June 3, 2025.

To Cite: Kathiresan P, Rathod S, Balhara YPS, et al. Impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on the mental health of middle-aged and older adults: a cross-sectional, comparative study. Prim Care Companion CNS Disord 2025;27(5):25m03963.

Author Affiliations: Department of Psychiatry, All India Institute of Medical Sciences, New Delhi, India (Kathiresan); Department of Research and Development, Hampshire and IOW Healthcare NHS Foundation Trust, Southampton, United Kingdom (Rathod); National Drug Dependence Treatment Centre, All India Institute of Medical Sciences, New Delhi, India (Balhara); Department of Psychology, Faculty of Environmental and Life Sciences, University of Southampton, Southampton, United Kingdom (Phiri); National Drug Dependence Treatment Centre, All India Institute of Medical Sciences, New Delhi, India (Bhargava).

Corresponding Author: Rachna Bhargava, PhD, National Drug Dependence Treatment Centre, All India Institute of Medical Sciences, Room No. 4096, Psychiatry Office, 4th Floor, Teaching Block, Ansari Nagar, New Delhi, India 110029 ([email protected]).

Relevant Financial Relationships: None.

Funding/Support: None.

Acknowledgment: The authors acknowledge the help of Elizabeth Graves, PhD, Southern Health NHS Foundation Trust, United Kingdom; Ashlea Brooks, Research Department, Clinical Trials Facility, Moorgreen Hospital, Southern Health NHS Foundation Trust, United Kingdom; Saseendran Pallikadavath, PhD, University of Portsmouth, Portsmouth, Hampshire, Great Britain; Megha Sharma, MPhil, PhD, Indira Gandhi National Open University, New Delhi, India; and Pranay Rathod, Patient and Public Involvement Representative, United Kingdom.

ORCID: Preethy Kathiresan: https://orcid.org/0000-0002-2952-0937; Shanaya Rathod: https://orcid.org/0000-0001-5126-3503; Yatan Pal Singh Balhara: https://orcid.org/0000-0003-1616-6403; Peter Phiri: https://orcid.org/0000-0001-9950-3254; Rachna Bhargava: https://orcid.org/0000-0003-3236-563X

Clinical Points

- Loneliness is strongly associated with depression and anxiety.

- Individuals with preexisting mental illness have a higher risk of depression and anxiety during a pandemic.

- Middle-aged adults are vulnerable to feelings of loneliness and seek quality interactions.

References (18)

- Salari N, Hosseinian-Far A, Jalali R, et al. Prevalence of stress, anxiety, depression among the general population during the COVID-19 pandemic: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Glob Health. 2020;16(1):57. PubMed CrossRef

- Nochaiwong S, Ruengorn C, Thavorn K, et al. Global prevalence of mental health issues among the general population during the coronavirus disease-2019 pandemic: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Sci Rep. 2021;11(1):10173. PubMed CrossRef

- Yu CC, Tou NX, Low JA. A comparative study on mental health and adaptability between older and younger adults during the COVID-19 circuit breaker in Singapore. BMC Public Health. 2022;22(1):507. PubMed CrossRef

- Dragioti E, Li H, Tsitsas G, et al. A large-scale meta-analytic atlas of mental health problems prevalence during the COVID-19 early pandemic. J Med Virol. 2022;94(5):1935–1949. PubMed CrossRef

- Vahia IV, Jeste DV, Reynolds CF III. Older adults and the mental health effects of COVID-19. JAMA. 2020;324(22):2253–2254. PubMed CrossRef

- Infurna FJ, Gerstorf D, Lachman ME. Midlife in the 2020s: opportunities and challenges. Am Psychol. 2020;75(4):470–485. PubMed CrossRef

- Rathod S, Pallikadavath S, Graves E, et al. Impact of lockdown relaxation and implementation of the face-covering policy on mental health: a United Kingdom COVID-19 study. World J Psychiatry. 2021;11(12):1346–1365. PubMed CrossRef

- Rathod S, Pallikadavath S, Young AH, et al. Psychological impact of COVID-19 pandemic: protocol and results of first three weeks from an international cross-section survey - focus on health professionals. J Affect Disord Rep. 2020;1:100005. PubMed CrossRef

- Kroenke K, Spitzer RL, Williams JB. The PHQ-9: validity of a brief depression severity measure. J Gen Intern Med. 2001;16(9):606–613. PubMed CrossRef

- Spitzer RL, Kroenke K, Williams JBW, et al. A brief measure for assessing generalized anxiety disorder: the GAD-7. Arch Intern Med. 2006;166(10):1092–1097. PubMed CrossRef

- Trucharte A, Calderón L, Cerezo E, et al. Three-item Loneliness Scale: psychometric properties and normative data of the Spanish version. Curr Psychol. 2023;42(9):7466–7474. PubMed CrossRef

- Neupert SD, Almeida DM, Charles ST. Age differences in reactivity to daily stressors: the role of personal control. J Gerontol B Psychol Sci Soc Sci. 2007;62(4):P216–P225. PubMed CrossRef

- Wickens CM, McDonald AJ, Elton-Marshall T, et al. Loneliness in the COVID-19 pandemic: associations with age, gender and their interaction. J Psychiatr Res. 2021;136:103–108. PubMed CrossRef

- Goutham S, Raghavan V. Prevalence and family factors associated with loneliness during COVID-19: a cross-sectional study from South India. Indian J Ment Health Neurosci. 2020;3(2):61–67.

- Beutel ME, Klein EM, Brähler E, et al. Loneliness in the general population: prevalence, determinants and relations to mental health. BMC Psychiatry. 2017;17(1):97. PubMed CrossRef

- van Tilburg TG, Steinmetz S, Stolte E, et al. Loneliness and mental health during the COVID-19 pandemic: a study among Dutch older adults. J Gerontol Ser B. 2021;76(7):e249–e255. PubMed CrossRef

- Heidinger T, Richter L. The effect of COVID-19 on loneliness in the elderly. An empirical comparison of pre-and peri-pandemic loneliness in Community-Dwelling Elderly. Front Psychol. 2020;11:585308. PubMed CrossRef

- Bhargava R, Kathiresan P, Balhara YP, et al. Impact of COVID-19 on mental health of aged population in India: an online, cross-sectional survey. World Soc Psychiatry. 2022;4(3):211–216.

Enjoy this premium PDF as part of your membership benefits!