Lessons Learned at the Interface of Medicine and Psychiatry

The Psychiatric Consultation Service at Massachusetts General Hospital sees medical and surgical inpatients with comorbid psychiatric symptoms and conditions. During their twice-weekly rounds, Dr Stern and other members of the Consultation Service discuss diagnosis and management of hospitalized patients with complex medical or surgical problems who also demonstrate psychiatric symptoms or conditions. These discussions have given rise to rounds reports that will prove useful for clinicians practicing at the interface of medicine and psychiatry.

Prim Care Companion CNS Disord 2026;28(1):25f04058

Author affiliations are listed at the end of this article.

Have you been struck by how disruptive impulsive behaviors are to interpersonal relationships, work and academic activities, and happiness? Have you wondered why impulsive behaviors occur and how they can be evaluated? Have you been uncertain about how best to manage impulsivity with medications and talking therapies? If you have, the following case vignette and discussion should prove useful.

CASE VIGNETTE

Mr A, a 72-year-old retired bus driver, was accompanied by his daughter for a psychiatric evaluation in a multidisciplinary primary care practice. She expressed growing concern over his uncharacteristic behaviors that emerged over the past year. A widower for the past 3 years, Mr A had long been described as responsible, frugal, and timid. However, recently, he made several impulsive purchases (eg, an expensive set of cookware advertised on a late-night infomercial) and multiple online gambling transactions that he initially tried to hide. His daughter discovered that he had withdrawn nearly $5,000 from his savings account without a clear plan or explanation for how these funds were to be used.

In addition to his spending, she noted a growing pattern of socially inappropriate behavior. He flirted excessively with a young waitress at a local diner, which prompted visible discomfort and apologies from his daughter, and recently, he made a crude joke during a church meeting that shocked longtime friends. She also reported that he occasionally walked out of the house with mismatched clothing and forgot to lock the door to the house (ie, highly uncharacteristic behavior for this meticulous man).

Mr A denied feeling distressed or out of control. When asked about the spending and gambling, he laughed and said, “What’s the point of saving if you’re already old?” He admitted to drinking more lately “to take the edge off” and occasionally lost track of how many beers he’d had. Mr A was not on any psychiatric medications, and he had no history of mental health treatment. His medical history included type II diabetes, hypertension, and hyperlipidemia, all reportedly well controlled.

On mental status examination, Mr A appeared superficially pleasant and cooperative, but he shifted rapidly between topics and offered tangential answers. He was fully oriented and scored 26/30 on the Mini-Mental State Examination,1 with mild deficits in attention and recall. His affect was full, and at times, he was inappropriate to the context. His daughter voiced concern that “something just isn’t right” and that he’s “not the same dad” she remembered—even if he seems more “cheerful” than usual.

DISCUSSION

What Types of Behaviors Can Be Characterized as Impulsive?

Most definitions of impulsivity make mention of actions without planning or reflection.2 Impulsivity is associated with impaired behavioral filtering3 and a compromised ability to reflect or to use intelligence or knowledge to direct behavior.4 Impulsivity can be divided into cognitive impulsivity (in which quick decisions are made, eg, rash, hasty, spontaneous, unpredictable, hot-headed, thoughtless); motor impulsivity (involving actions without premeditation, eg, non-premeditated physical aggressivity); and nonplanned impulsivity (with a lack of consideration about the future).5 Impulsivity typically involves rapid, unplanned, and poorly thought-out actions occurring in response to internal or external triggers. In contrast, compulsivity refers to repetitive, ritualistic behaviors driven by a perceived need to reduce distress or prevent a feared outcome, even when recognized as irrational. While some overlap exists, these dimensions remain clinically distinguishable when evaluated comprehensively, including the use of structured assessments and screening for co-occurring conditions as described below.

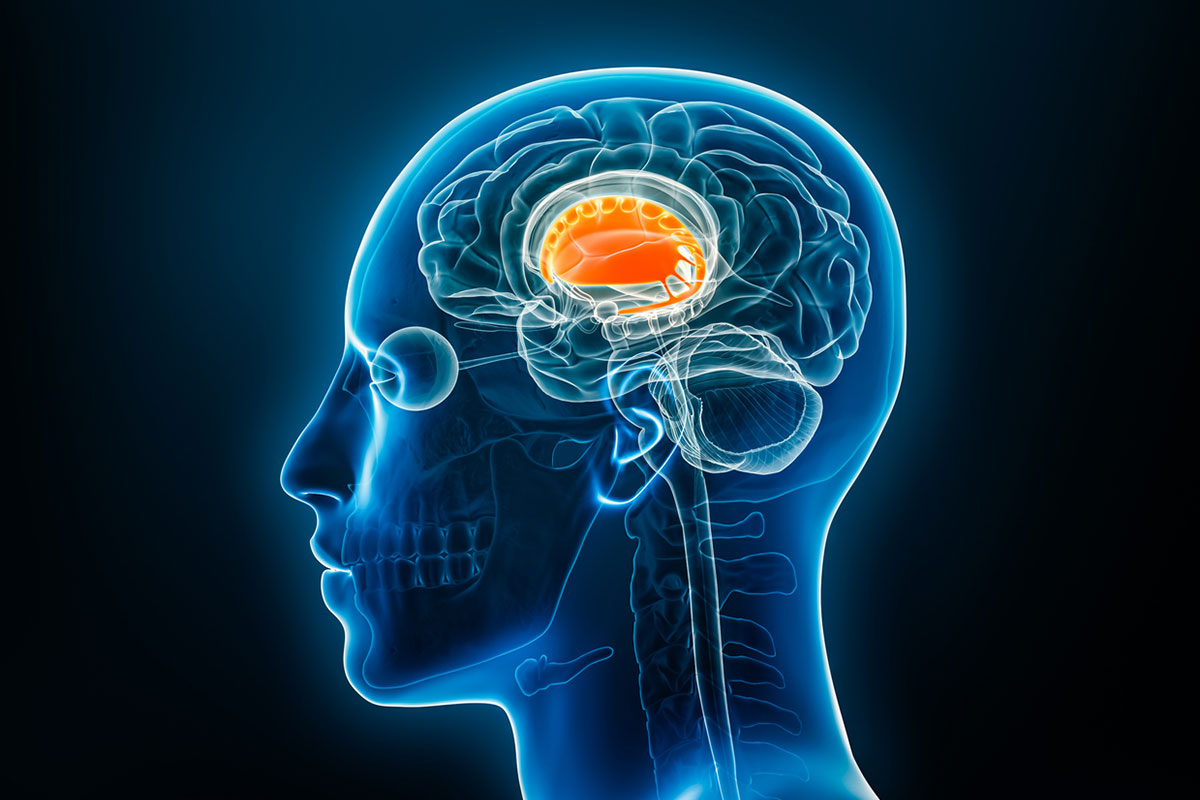

Which Neuroanatomical Circuits Regulate Impulse Control?

Impulsivity is a multidimensional construct that spans psychiatric, neurodevelopmental, and neurodegenerative disorders.6 It plays a central role in several conditions that are manifested throughout the lifespan (eg, attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder [ADHD], borderline personality disorder and antisocial personality disorder [APD], eating disorders, bipolar disorder, substance use disorders [SUDs], and major neurocognitive disorders). While often viewed as a trait, impulsivity also reflects state-dependent changes that are influenced by mood, context, and neurobiology.6 Across these varied conditions, impulsivity involves having difficulty delaying gratification, impaired judgment, and failure to inhibit inappropriate actions—behaviors that can range from mildly disruptive to seriously harmful.6

In bipolar disorder, impulsivity is a hallmark feature, contributing to impaired functioning and an increased risk of adverse outcomes. Neuroimaging studies reveal that individuals with bipolar disorder show underactivation in key frontal, parietal, and cingulate regions during tasks that require rapid-response inhibition (eg, the Go/No-Go and Stop-Signal tasks).7 These deficits can persist across mood states, suggesting trait-like abnormalities in cognitive control. However, when tasks involve emotionally salient stimuli, individuals with bipolar disorder exhibit paradoxical overactivation in similar regions, pointing to a mood-congruent amplification of impulsive tendencies.7

In contrast, impulsivity in older adults often signals an emerging neurodegenerative process. In a longitudinal study of psychiatric outpatients over the age of 60 years, Tamam and colleagues found that more than 20% met criteria for at least 1 impulse control disorder (ICD), with intermittent explosive disorder (IED) and pathological gambling being the most prevalent.8 These findings underscore that impulsivity in late life should prompt a careful evaluation, especially in the context of mild cognitive impairment (MCI) or a suspected dementia.

Neurobiologically, impulsivity reflects dysfunction in multiple brain circuits. The ventral frontostriatal system, including the orbitofrontal cortex, nucleus accumbens, and ventromedial prefrontal cortex (PFC), is associated with reward processing and delay discounting, which contributes to “waiting” impulsivity.9 Meanwhile, the dorsal prefrontal and inferior frontal gyrus circuits support inhibitory control and action monitoring, and their dysfunction leads to “stopping” impulsivity.9 While the underlying etiology may vary—from developmental neurobiology to mood dysregulation to neurodegeneration—the convergence of circuit-level dysfunction provides a framework for understanding and targeting impulsivity across diagnostic boundaries.

Which Psychiatric and Neuropsychiatric Conditions Are Characterized by Urges and Impulsive Acts?

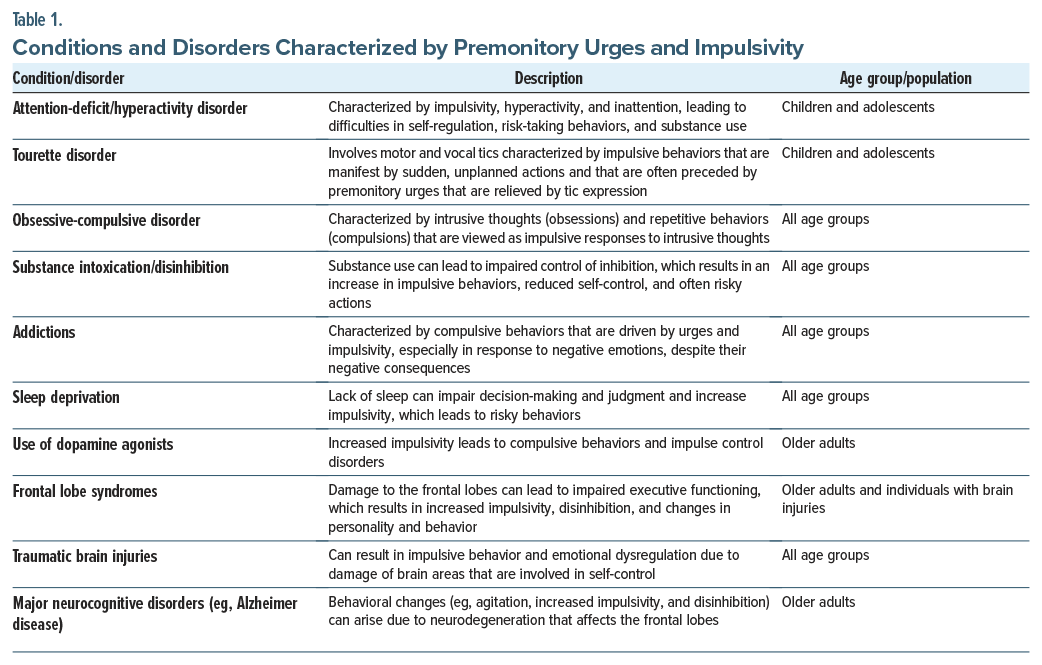

A bevy of psychiatric and neuropsychiatric conditions, characterized by urges and impulsivity, arise in individuals across the lifespan. These conditions are influenced by complex neurobiological, psychological, and environmental factors (Table 1).

Among these disorders, ADHD is one of the most well-studied. Individuals with ADHD and its accompanying impulsivity (which is associated with dysfunctional frontostriatal circuitry and executive dysfunction)10 often have impaired academic performances, social relationships, and daily functioning. This difficulty with self-regulation also contributes to an increase in risk-taking behaviors and the development of co-occurring SUDs.

Similarly, Tourette disorder presents with impulsive behaviors, which are often manifest by sudden, unplanned actions that are preceded by urges. These actions may be understood as attempts to alleviate discomfort or tension associated with these urges; however, they can also interfere with social and academic functioning. The overlap between Tourette disorder, ADHD, and obsessive-compulsive disorder (OCD) suggests that they share neurobiological underpinnings, which involve dopaminergic dysregulation.11

OCD presents another dimension of impulsivity, in which compulsive behaviors often coexist with impulsive tendencies. This interplay between impulsivity and compulsivity, which is driven by deficits in inhibitory control, highlights the shared mechanisms in disorders that involve frontostriatal dysfunction.12 The resulting compulsive and impulsive actions can interfere with daily functioning and cause significant distress.

SUDs illustrate the bidirectional relationship between impulsivity and addiction. Acute intoxication impairs inhibitory control and increases impulsive behaviors, while the chronic use of substances exacerbates impulsivity through neurobiological changes in the brain’s reward pathway, which involve the dopaminergic pathway of the ventral tegmental area and nucleus accumbens. These changes are particularly pronounced in frontostriatal and mesolimbic systems.13 In addition, compulsivity in addiction reinforces the cycle of substance use, as individuals struggle to overcome powerful urges despite experiencing negative consequences. The relationship between impulsivity and addictive behaviors (eg, gambling or internet gaming) parallels that of SUDs. Dysfunctional dopaminergic systems and altered reward processing contribute to both impulsive and compulsive behaviors in these disorders.12

Frontal lobe syndromes, including those caused by traumatic brain injuries (TBIs), neurodegenerative dementias, or strokes, are associated with profound deficits in inhibitory control. Damage to the orbitofrontal cortex and anterior cingulate cortex, key regions involved in impulse regulation, leads to behavioral disinhibition and impulsivity.14 This is particularly evident in certain conditions, such as frontotemporal dementia, where cognitive impairment and deficits in behavioral inhibition adversely impact the lives of patients.

In the context of Parkinson disease, the use of dopaminergic agonists has been associated with ICDs, such as pathological gambling and compulsive shopping. The preferential stimulation of dopamine D3 receptors by these medications underlies this phenomenon, as these receptors are integral to reward processing and impulsivity.15

How Might Impulsive Behaviors Be Evaluated?

Taking a history from patients who exhibit signs and symptoms of impulsivity should include a focused and pragmatic assessment to determine the nature of the clinical presentation.16 Impulsivity can be fleeting (eg, restricted to certain situations), specific, and context dependent vs. stable (eg, general, pervasive, wide ranging, unspecific, ubiquitous, and potentially more treatment refractory). Clinically based impulsivity is neuropsychiatric or mental illness–related, while trait-based impulsivity is related to maladaptive personality features/disorders, and it generally requires more intensive interventions. All assessments of impulsive patients should include a thorough assessment of the risk for suicide and homicide (including access to means and protective factors). Brokke and colleagues examined the relationship between impulsivity, aggression, and the lethality of suicide attempts.17 Their findings suggested that physical and hostility-related aggressions were significantly elevated in individuals with high-lethality suicide attempts compared to suicide ideators, especially among women.17 Impulsivity also plays a role in homicidal behaviors, particularly when coupled with antisocial traits. One study found that the combination of lifestyle, behavioral, and antisocial or psychopathic traits, along with specific dimensions of impulsivity such as poor self-control, may be especially important in distinguishing youth who commit severe antisocial behaviors, including homicide, from those without prior criminal activity.18 Despite this, there remains a paucity of contemporary literature quantifying the relationship between impulsivity and rates of homicidal behavior, warranting further investigation. Additional questions can help to identify a range of conditions that can lead to impulsivity (Table 1).16

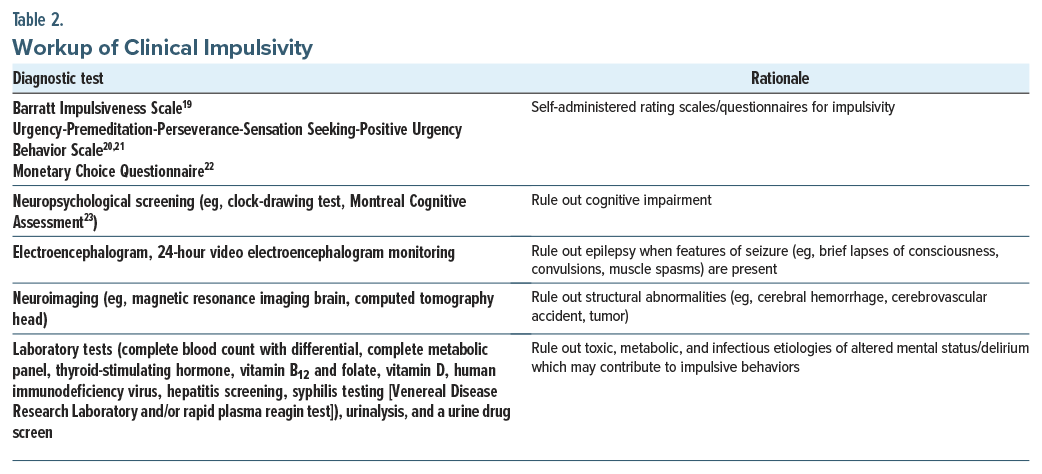

Additional areas of inquiry can include questions regarding complications at birth, developmental delays, autism spectrum disorders (ASDs), and precipitants for impulsivity (eg, the use of medications and substances); see Table 2 for a workup of impulsivity. Recommended tools for assessing impulsivity include the Barratt Impulsiveness Scale,19 Urgency-Premeditation-Perseverance-Sensation Seeking-Positive Urgency Behavior Scale,20,21 Monetary Choice Questionnaire,22 and Montreal Cognitive Assessment,23 as well as relevant neuroimaging and laboratory evaluations (Table 2).

How Might Impulsive Behaviors Interfere With Intrapsychic and Interpersonal Functioning and Academic and Work Performance?

Impulsive behaviors undermine an individual’s ability to reflect, regulate emotions, and maintain stable and trusting relationships. Internally (intrapsychically), impulsivity limits self-awareness and emotional control, making it difficult to tolerate frustration, delay gratification, or engage in long-term planning. Self-control is a multidimensional construct spanning psychology, neuroscience, and education—encompassing delayed gratification, impulse control, conscientiousness, executive function, willpower, and behavioral self-regulation.24,25 Theories of normative development suggest that self-control begins during toddlerhood (ages 1–3 years), with the emergence of self-awareness and object constancy. It strengthens through early childhood (ages 3–6 years) with language, play, and imagination and further develops during the latency years (ages 6–10 years), when children begin to substitute thoughts for behaviors and manage impulses. They then focus on peer relationships and intellectual growth. During preadolescent and adolescent (10–18 years) years, the body, mind, and emotional life further evolve with enhanced emotional regulation, decision-making, and long-term goal setting. Late in this phase, self-control is tested by social and media influences, as teens form identity and values independent of caregivers, while becoming more prone to engaging in risky behaviors. Mastery of self-control across these stages lays the foundation for adult milestones—independent living, marriage, family, and career.24-27

In the longitudinal Dunedin study, Moffitt and colleagues assessed childhood self-control across several decades to examine its predictive power for adult outcomes (eg, health, wealth, and criminal acts). They found that lower self-control in childhood predicted their socioeconomic status, adult health problems later in life, and a higher likelihood of criminal conviction in adulthood even after controlling for social class and IQ.25

How Might Impulsive Behaviors Interfere With Interpersonal Relationships?

Externalizing disorders (eg, ADHD, oppositional defiant disorder [ODD], and conduct disorders [CDs]) are often diagnosed in childhood and can persist through adulthood, while adversely affecting functional outcomes. Problematic behaviors involving impulsivity, inattention, and aggression impair an individual’s ability to focus on tasks that require sustained mental effort for learning. These behaviors are linked to deficits in executive function, which affect students’ ability to organize, leading to poor time management, incomplete assignments, or rushed and error-filled work. Because of their inability to delay gratification, these students often become disruptive in classrooms or during organized activities with peers. They may react strongly to frustration, leading to withdrawal, rejection, or conflict with peers. Consequently, such children may face adverse reactions from others, academic challenges, and disengagement from educational, family, and social networks. This leads to lower intellectual scores, poor vocational achievements and productivity, a higher probability of poor job retention, unemployment as an adult, and a greater risk for debt and credit card problems. Comorbid mood and anxiety symptoms, anger, substance abuse, and other problematic behaviors related to impulsivity may also lead to affiliation with deviant peers who are searching for belonging later in life, causing further functional decline and low productivity.25,28-30

Impulsivity is linked to poor interpersonal relationships, low or unstable self-image, and emotional dysregulation. This individual’s difficulty relating to others leads to conflicts and isolation. Trust and reliability are often adversely affected due to the volatile or unpredictable nature of their interactions, which swing from overdependence to clinginess to sudden withdrawal to acting out. These patterns are frequently present in those with borderline personality disorder, which has been associated with attachment difficulties in childhood.29 However, when impulsivity occurs later in life, with or without cognitive deficits, a prodromal or predementia syndrome should be considered.31

How Can Impulsivity Be Managed?

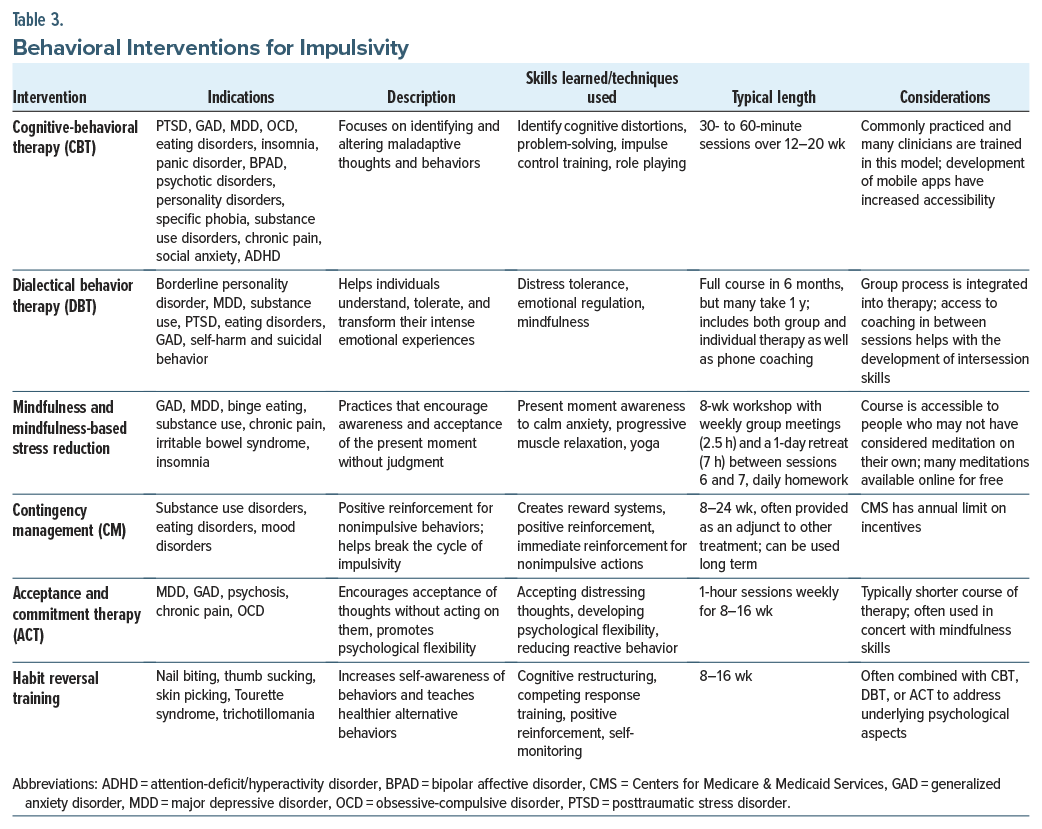

Although there is no standard treatment algorithm for impulsivity, managing impulsivity often involves a combination of behavioral strategies, anxiety reduction techniques, and pharmacologic interventions. In the following section, we review the behavioral interventions that have evidence for, and have been trialed in, impulsivity (Table 3). Details on each of the treatments, indications, descriptions, skills and techniques, length, and considerations are provided.

Behavioral Therapies for Impulsivity

Cognitive-behavioral therapy. Cognitive-behavioral therapy (CBT) reduces impulsivity by helping individuals identify and challenge the thoughts that drive impulsive behavior, develop delayed gratification skills, improve emotional regulation, and build self-control. Through techniques (such as cognitive restructuring, behavioral interventions, problem-solving, and emotional awareness), CBT helps people become more mindful of their impulses and learn to be more thoughtful and intentional, rather than reacting impulsively. Over time, these skills reduce impulsive behavior and provide a greater sense of control over actions. CBT is effective for the treatment of several psychiatric conditions, including mood disorders, eating disorders, SUDs, personality disorders, and psychotic disorders. A meta-analysis of 14 randomized controlled trials (RCTs) on CBT for adults with ADHD suggested that CBT may help with core symptoms of ADHD, including impulsivity.32 There is limited, but promising, evidence for using CBT to treat primary ICDs, such as kleptomania, compulsive buying, and gambling.33

Dialectical behavior therapy. Dialectical behavior therapy (DBT) treats impulsivity by teaching individual skills in mindfulness, distress tolerance, emotional regulation, interpersonal effectiveness, and values-based action.34 These skills help people become more aware of their emotions and impulses, tolerate distress without reacting impulsively, and make decisions that align with their long-term goals and values. DBT empowers individuals to manage impulsivity more effectively, leading to more thoughtful and intentional responses rather than automatic reactions.

Originally developed to treat emotional dysregulation and self-injurious behaviors in individuals with borderline personality disorder, DBT is also effective for those who are impulsive in the context of SUDs, binge-eating disorders (BEDs), and geriatric depression.35–37 Its focus on mindfulness and self-regulation makes DBT particularly effective for the treatment of trauma-related impulsivity, as seen in posttraumatic stress disorder.36 DBT techniques can also improve self-reported measures of ADHD and improve measures of executive function, as well as self-reported measures of impulsivity.37–40

Mindfulness and mindfulness-based stress reduction. Mindfulness reduces impulsivity by enhancing awareness of thoughts and emotions, providing tools to pause before acting, improving emotional regulation, and fostering self-compassion. By practicing mindfulness on a regular basis, people can become better at observing their impulses, recognizing them as transient experiences, and making more intentional and thoughtful choices rather than acting on impulsive behaviors. Mindfulness and mindfulness-based stress reduction (MBSR) has been used to treat depression, anxiety, ADHD, and SUDs, each of which can drive impulsive behaviors.41–43 Neuroimaging studies have demonstrated that mindfulness induces changes in several brain structures.44 Brain imaging research has also revealed that 5 weeks of mindfulness practice can reduce impulsivity and induce structural changes in the caudate nucleus, which were correlated with a subjective report of a change in mindful behavior.45 MBSR programs are highly structured, weekly 2.5-hour group sessions, with homework and a 1-day retreat. Although many MBSR programs are costly and not reimbursed by insurance, low-or no-cost options are available.

Contingency management. Contingency management (CM) works by reinforcing self-control and thoughtful decision-making, while decreasing the immediate rewards that impulsivity typically seeks. People learn to associate these behaviors with positive outcomes by consistently receiving rewards for exhibiting self-control or thoughtful decision-making. Over time, this shifts behavior, helping individuals manage their impulses better and make choices that align more with their values. CM has been studied primarily in those with SUDs.46 CM is often tailored to target specific behaviors related to impulsivity, such as seen in SUDs, anorexia nervosa, eating disorders, and gambling.46-48

Acceptance and commitment therapy. Acceptance and commitment therapy (ACT) encourages individuals to accept their thoughts and feelings without judgment, while acting in accordance with their values. ACT treats impulsivity by helping individuals accept their thoughts and emotions without reacting to them, encouraging mindfulness and present-moment awareness, and fostering greater psychological flexibility. By learning to accept rather than to act on impulses, to defuse from automatic thoughts, and to commit to values-based action, people can make more intentional choices rather than reacting impulsively.49

Fewer studies have investigated the use of ACT for primary impulsive behaviors, although it has been used extensively to treat mood disorders, chronic pain, and OCD. ACT has shown promising results on impulsivity in those with bipolar disorder or ADHD.50,51 A recent study of ACT in those with problematic impulsivity (eg, eating habits, problematic pornography use, ineffective communication strategies) showed that a brief ACT intervention decreased problematic behaviors in most measures.49

Habit reversal training. Habit reversal training (HRT) can be highly effective for managing impulsivity, especially in situations where the impulsivity leads to problematic behaviors (eg, tics, compulsions, or self-destructive actions). It is commonly used for Tourette syndrome, trichotillomania, and skin-picking disorder.52 HRT helps individuals become more aware of their urges, replaces impulsive behaviors with more adaptive, controlled responses, and encourages practicing those habits in real-world situations. Over time, impulsive behaviors diminish as the person learns to manage their urges more effectively, improving their ability to make deliberate choices.

Pharmacologic Treatments for Impulsivity

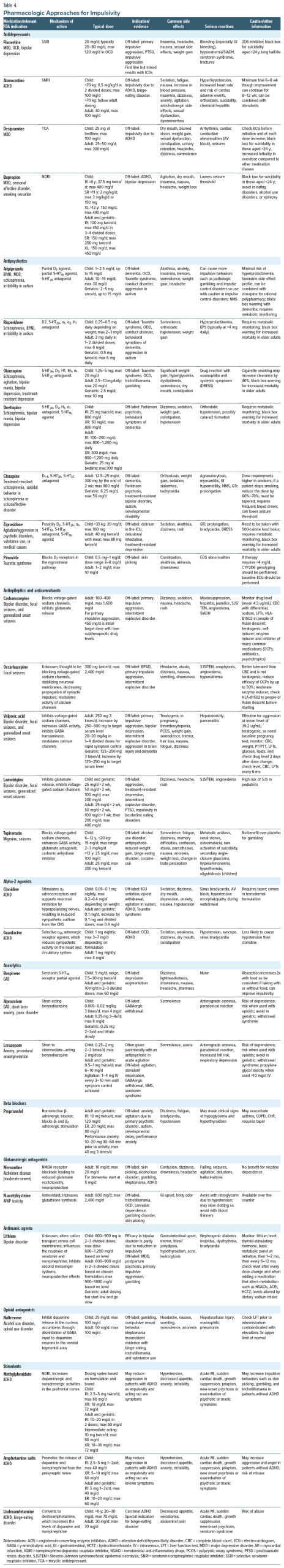

Unfortunately, there are no well-accepted recommendations for evidence-based treatments for ICDs.53 Pharmacologic treatments for impulsivity should be tailored to the cause, if it can be identified. In the following section, we review the pharmacologic approaches that have been trialed in impulsivity (Table 4). Details on each medication class, US Food and Drug Administration (FDA)–approved indications, off-label uses, dosing, side effects, and relative contraindications are provided.

First-line medications include selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs) for mood-and anxiety-related impulsivity, while mood stabilizers are used for impulsivity seen in bipolar spectrum illness or with impulsive aggression. Serotonin-norepinephrine reuptake inhibitors (SNRIs) and clonidine may reduce impulsivity that is seen in ADHD. Antipsychotics are often used, but the evidence for their use is mixed. Anxiolytics may provide short-term relief for anxiety-driven impulsivity, although caution is required due to the risk of dependency. Stimulants often reduce impulsivity related to ADHD, although they may exacerbate other impulsive behaviors. APD, ODD, and CD are also considered to be ICDs in the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fifth Edition, although the evidence base for these disorders is small, and few recommendations can be given.

Antidepressants

SSRIs are among the most commonly prescribed medications for impulsivity, although the evidence for their efficacy remains limited. These medications work by increasing serotonergic transmission, which is thought to enhance impulse control and emotional regulation. SSRIs and SNRIs can be particularly helpful in treating impulsivity when it is associated with depression, anxiety, bipolar disorder, borderline personality disorder, and IED.

Fluoxetine is the most commonly used antidepressant for impulsivity and impulsive aggression, although the evidence for using antidepressants to treat ICDs is mixed. It has shown promising results regarding reducing impulsive aggression, and it is recommended as a first-line treatment for mild-moderate impulsive aggression.54,55 Other medications (including phenytoin, oxcarbazepine, carbamazepine, lamotrigine, topiramate, valproate, or lithium) may also be considered.55

While mood stabilizers are the first-line treatment for bipolar disorder, antidepressants, such as bupropion, may reduce impulsivity during depressive phases by improving mood and reducing risky behaviors, including reckless spending or substance use. While stimulants are first-line treatment for ADHD, SNRIs (such as atomoxetine and desipramine) and the norepinephrine-dopamine reuptake inhibitor bupropion can be beneficial for individuals with co-occurring depression or anxiety, although only atomoxetine is FDA approved for ADHD. Because stimulants may exacerbate other impulsive behaviors (like skin picking or trichotillomania), an SNRI may be a better option in these cases.

When prescribing a serotonergic antidepressant, higher doses may be needed to achieve the desired effect on impulsivity. As such, although SSRIs and SNRIs are generally well tolerated, side effects (eg, weight gain, sexual dysfunction, insomnia, gastrointestinal [GI] upset, and headaches) may arise. While bupropion is weight neutral and lacks sexual side effects, it is renally excreted and relatively contraindicated in those with eating disorders and alcohol use disorder (AUD) due to its propensity to lower the seizure threshold. In addition, fluoxetine, a cytochrome (CYP) P450 2D6 inhibitor, can interact with commonly prescribed medications, including warfarin. Serotonergic antidepressants may also reduce platelet aggregation, which slightly increases the risk of bleeding, although this is rarely clinically significant.

Antipsychotics

Antipsychotics modulate dopamine activity, which plays a key role in reward processing, motivation, and impulse control. Dopaminergic antagonism can reduce impulsive behaviors, particularly when these behaviors are linked to psychosis, mania, mood dysregulation, or behavioral disinhibition.56 Atypical antipsychotics are commonly used as antimanic agents and mood stabilizers and help in the management of both mood instability and impulsivity. These medications can reduce impulsive, high-risk behaviors associated with mania (eg, spending sprees, reckless driving, and impulsive sexual behavior). By modulating dopamine and serotonin pathways, antipsychotics reduce the emotional intensity that often drives such actions. Two antipsychotics, aripiprazole and risperidone, are FDA approved for impulsivity-related syndromes, specifically for managing irritability in ASD. Aripiprazole is typically recommended as a first-line option due to its favorable side effect profile and its relatively lower risk of inducing a metabolic syndrome, which makes it better suited for long-term use.

In schizophrenia and schizoaffective disorder, impulsivity may stem from disorganized thinking, delusions, or hallucinations. By alleviating the severity of psychotic symptoms, antipsychotics help individuals to think more clearly and to reduce impulsive behaviors that are tied to psychotic episodes. For individuals with borderline personality disorder, impulsive aggression and emotional dysregulation are common. Antipsychotics (eg, aripiprazole, quetiapine, olanzapine, and ziprasidone) may be helpful in managing these symptoms, particularly by stabilizing mood and reducing emotional reactivity. This can lead to better control over anger, impulsive outbursts, and interpersonal impulsivity. Clozapine has also been studied in those with impulsive aggression associated with APD, although pharmacologic treatment is not routinely recommended as a first-line option in this patient population.57

Antipsychotics are often used off-label to treat a variety of conditions. In the case of primary ICDs, pimozide is commonly used off-label for skin-picking, while olanzapine and quetiapine have been used for trichotillomania. Aripiprazole, risperidone, and quetiapine are used to treat behavioral symptoms of dementia. Both aripiprazole and risperidone are used off-label for the behavioral symptoms of dementia. While aripiprazole and risperidone have comparable efficacy for this use, aripiprazole is typically tried first.58 Quetiapine and clozapine can be especially helpful in those with Parkinson disease with psychosis owing to the lack of D2 antagonism allowing them to be used more safely in this population. Antipsychotics are the mainstay of treatment for hyperactive delirium in the hospital setting.

Despite their usefulness, the off-label use of antipsychotics is limited by their side effect profile, particularly in children, adolescents, and young adults. Antipsychotics are associated with weight gain, hyperlipidemia, hyperglycemia, and an elevated risk of metabolic syndrome. Although less common with second-generation antipsychotics, they can induce a risk of extrapyramidal symptoms, parkinsonism, and tardive dyskinesia. Some antipsychotics can also prolong the QT interval, which increases the risk of arrhythmias. In addition, all antipsychotics carry a black box warning for the risk of sudden death in the elderly, mainly due to cardiovascular events. Long-term use, particularly at high doses, has been associated with an increased risk of cognitive dysfunction.59 In addition, third-generation antipsychotics (eg, aripiprazole, brexpiprazole, and cariprazine), which are dopamine partial agonists, may paradoxically increase impulsivity and lead to pathological gambling, compulsive shopping, hyperphagia, or hypersexuality.60

Antiepileptic Drugs and Anticonvulsants

Antiepileptic drugs (AEDs) can manage impulsivity effectively, particularly in individuals with bipolar disorder, borderline personality disorder, epilepsy, CD, IED, and other primary ICDs. Medications (eg, valproate, lamotrigine, topiramate, and carbamazepine) can stabilize mood, reduce aggression, and improve emotional regulation, each of which contributes to a reduction in impulsive behaviors.

Several AEDs (including lamotrigine, valproate, and carbamazepine) are commonly used as mood stabilizers in bipolar disorder and are used off-label in those with borderline personality disorder. In borderline personality disorder, which is often characterized by intense emotional reactions and impulsive behaviors, AEDs (eg, lamotrigine or valproate) may reduce emotional reactivity and improve impulse control. By stabilizing mood and preventing rapid emotional shifts, these medications make it easier for individuals to manage emotional responses, particularly in situations involving anger, frustration, or other intense emotions. This can reduce impulsivity, as well as self-destructive behaviors (eg, self-harm or reckless actions), which are often driven by intense emotions.

Certain AEDs also have antiaggressive properties. Valproate, for example, has reduced impulsive aggression in children, adults, and older adults, although it has shown little effect when studied in primary impulsive disorders.53 Other medications (including oxcarbazepine, carbamazepine, lamotrigine, topiramate, and lithium) are also used to manage severe impulsive aggression, as seen in IED.55 Topiramate may reduce impulsive behaviors associated with BED, alcohol dependence, and cocaine use. Valproate has also been used off-label for the management of dysregulated behaviors in those with brain injuries or behavioral symptoms of dementia. In individuals with epilepsy, particularly those with temporal lobe epilepsy, AEDs can control seizures and reduce impulsivity that may be triggered by these episodes. Given the good evidence for impulsive aggression with anticonvulsants and fluoxetine, these medications may be first-line agents for unspecified impulsivity without a clear psychiatric syndrome.

AEDs carry the potential for significant drug-drug interactions and adverse effects. Common side effects include dizziness, drowsiness, weight gain, cognitive slowing, and GI upset. Enzyme-inducing AEDs (eg, the teratogenic carbamazepine [affecting CYP 3A4]) stimulate the metabolism of most other concurrently administered AEDs (including valproate, lamotrigine, topiramate, oxcarbazepine, carbamazepine itself via autoinduction, as well as oral contraceptives [OCPs], antibiotics, antineoplastics, and other psychotropics). Notably, AEDs may interact with OCPs (in the case of carbamazepine, oxcarbazepine, and topiramate). Valproate and lamotrigine have a significant interaction that requires careful management. While oxcarbazepine is a less potent enzyme inducer than carbamazepine, it still reduces the efficacy of OCPs so that patients must seek alternative forms of contraception. Both oxcarbazepine and carbamazepine carry a risk of Stevens-Johnson syndrome. Valproate is a potent teratogen, and caution is advised when using this medication in women of childbearing age. Serious side effects include hyperammonemia, hepatotoxicity, and pancreatitis.

Alpha Agonists

Alpha-2 agonists (eg, clonidine and guanfacine) modulate impulsivity through regulating subcortical activity in the PFC and influencing noradrenergic and dopaminergic systems.61 The PFC is responsible for higher-order cognitive functions (eg, planning, decision-making, and impulse control), playing a key role in attention, self-control, and emotional regulation. This mechanism is particularly beneficial in ADHD, where impulsive behaviors (eg, acting without thinking, interrupting others, and difficulty waiting one’s turn) are common. By enhancing focus and attention on relevant tasks, α agonists enable individuals to regulate their behavior and resist impulsive urges during activities that require sustained attention. Alpha agonists may be considered as second-line agents for ADHD when stimulants are either ineffective or cause intolerable side effects. Both clonidine and guanfacine, whether used as monotherapy or adjunctively, improve symptoms of ADHD (eg, focus, impulse control, and frustration tolerance).61,62

In addition to its use in ADHD, clonidine is used off-label for Tourette syndrome, where impulsivity may accompany tics or compulsive behaviors. In this context, clonidine can reduce impulsivity and manage associated behavioral symptoms. For children with ODD who exhibit impulsive defiance and aggression, α agonists can enhance impulse control and emotional regulation.63

As the primary indication for these medications is hypertension, cardiovascular side effects are common. Hypotension is common with both clonidine and guanfacine, and both require tapering before they are discontinued, due to the risk of rebound hypertension. Clonidine is available in both oral and transdermal formulations, which can be particularly helpful for the treatment of children or older adults. Guanfacine, on the other hand, is less likely to cause hypotension than clonidine, which makes it a preferred option for some individuals.

Anxiolytics

Anxiolytics (eg, benzodiazepines and buspirone) can reduce anxiety, calm emotional reactivity, and prevent impulsive actions that are driven by anxiety. In anxiety-related disorders like generalized anxiety disorder (GAD), panic disorder, and social anxiety, individuals often act impulsively to cope with overwhelming emotions or with anxiety-triggered situations. Anxiety can impair cognitive functioning (eg, decision-making and clear thinking). Anxiolytics help individuals slow down, think through their actions, and avoid impulsivity by addressing underlying anxiety.

Benzodiazepines work by increasing γ-aminobutyric acid type A receptor activity. This makes them particularly useful in acute situations where anxiety and impulsivity are heightened (eg, during panic attacks). Benzodiazepines are most effective for short-term management of impulsivity (including impulsive aggression, panic-related behaviors, and self-destructive actions that result from sudden and severe anxiety). They are recommended for short-term use; long-term use can lead to tolerance, dependence, and cognitive impairment.

Buspirone, a serotonin 5-HT1A receptor partial agonist, targets anxiety without causing sedation. It is FDA approved for the management of GAD. This makes it a useful option for the long-term management of anxiety-related impulsivity without the risk of drowsiness or dependence. It is generally well tolerated, although its absorption is increased when taken with food, so it is important to be consistent with taking it with or without food. Buspirone is generally well tolerated, although it is often underdosed and underutilized in clinical practice.

Beta Blockers

Beta blockers (eg, propranolol) are competitive antagonists of noradrenaline and adrenaline at β-adrenergic receptors. These medications are used off-label as an adjunctive medication to manage impulsivity by reducing physiological arousal, which can help to control anxiety-induced impulsivity and impulsive aggression in those with psychosis or developmental disabilities.

Anxiety often manifests with physical symptoms (eg, restlessness, muscle tension, sweating, tremulousness, rapid heartbeat, and hypervigilance), which can contribute to impulsive behavior. By calming these physical symptoms, beta blockers reduce the urgency that often drives impulsivity. This is particularly beneficial for individuals prone to impulsive aggression or outbursts, as reducing physical arousal may help them control their emotions and reactions better in stressful situations. While metoprolol, atenolol, and propranolol can be used for performance anxiety, propranolol is most often used for adjunctive treatment with agitation and impulsivity, especially in patients with schizophrenia and ASD, sometimes in doses up to 200 mg 3 times per day.64

Although beta blockers can help in the management of impulsivity by reducing anxiety and physiological arousal without the risk of dependence, there are a paucity of RCTs that provide high-quality evidence to support the use of beta blockers for the treatment of impulsivity and outbursts. As such, there is no standardized dose range for this indication. Common side effects include hypotension, fatigue, bradycardia, and, in some cases, depression.

Glutamatergic Antagonists

Glutamate plays a key role in synaptic plasticity, learning, and memory, and it influences excitability in brain circuits that regulate impulse control. Excessive glutamatergic activity can lead to hyperactivity, impulsivity, and poor inhibition, particularly in regions like the PFC, which is involved in decision-making and impulse control. Disruptions in glutamatergic signaling, particularly in the PFC, have been implicated in disorders characterized by poor impulse control and behavioral disinhibition, such as ADHD, TBIs, and SUDs. By modulating glutamate, glutamatergic antagonists may enhance PFC function, improving the ability to inhibit impulsive behaviors.

N-methyl-D-aspartate (NMDA) receptors, which are subtypes of glutamate receptors, mediate excitatory neurotransmission and are critical for synaptic plasticity and memory. NMDA receptor antagonists help reduce excessive glutamate activity in these areas, calming overactive brain regions and improving impulse regulation. Memantine, an NMDA receptor antagonist, is FDA approved for the treatment of moderate to severe Alzheimer dementia. Recent studies, though limited, have explored its potential in managing impulsivity in other conditions. For example, it has been investigated for ADHD (measured via the Connors Rating Scale), opioid use disorder (OUD) (where it has been shown to reduce cravings and increase program participation), and improvements in the Glasgow Coma Scale for TBIs.65–67 Though promising, evidence for its use in primary ICDs (eg, skin picking, gambling, and kleptomania) remains limited.

N-acetylcysteine (NAC) is an antioxidant that increases glutathione synthesis that is typically used with acetaminophen overdose. Used off-label and available over the counter, NAC has shown potential for the treatment of OCD, trichotillomania, skin-picking disorder, and other body-focused repetitive behaviors.68 Similarly, NAC may show promise for treating cannabis use disorder, although results are mixed.69 As with any supplement, it should be purchased from reputable sources.

Lithium

Lithium is an FDA-approved antimanic agent used to treat mania and for BPAD maintenance. It stabilizes mood by influencing the balance of serotonin, dopamine, and glutamate. One of its key benefits in bipolar disorder is its ability to reduce impulsivity, a hallmark of mania, as well as impulsive aggression. Lithium is used off-label for managing impulsive aggression in conditions like IED. For severe impulsivity, especially when it leads to assaultive behavior or property destruction, lithium is often considered alongside anticonvulsants.55,70 For individuals prone to aggressive actions without considering the consequences, lithium can facilitate better impulse control, leading to more measured responses to frustration or anger.

In borderline personality disorder, where impulsivity and emotional dysregulation are prominent, lithium may help reduce self-harm, reckless behavior, and interpersonal impulsivity. Although not a first-line treatment for borderline personality disorder, lithium can stabilize mood and reduce volatility, which helps manage impulsive behaviors that are driven by the fear of abandonment or frustration. Additionally, lithium has shown promise in reducing impulsive behaviors in individuals with SUDs, particularly AUD, by stabilizing mood and reducing cravings and impulsive drug-seeking behaviors. There is also emerging research suggesting that lithium may reduce thoughts of suicide and may be effective even with subtherapeutic doses.

While effective, lithium requires careful monitoring due to its potential side effects (eg, thyroid dysfunction, renal toxicity, weight gain, tremors, cognitive slowing, GI upset, polyuria, and polydipsia). Regular monitoring of blood levels is essential to ensure that lithium levels remain within a narrow therapeutic range to avoid toxicity. Because of this, lithium is not recommended for individuals who cannot commit to regular blood draws or those who drink alcohol regularly. Caution is also advised when prescribing lithium along with thiazide diuretics, angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors, or nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, as these agents increase the risk of lithium toxicity.

Opioid Antagonists

Opioid antagonists, eg, naltrexone, can reduce impulsivity by blocking the rewarding effects of certain behaviors, eg, alcohol and opioid use, gambling, binge eating, and kleptomania. These medications reduce the reinforcement associated with impulsive behaviors by targeting the endogenous opioid system, which is integrated with the mesolimbic pathway. By reducing these reinforcing effects, opioid antagonists help individuals make more measured decisions and reduce impulsivity. Naltrexone is FDA approved for treating AUD and OUD. It is also used off-label for several conditions (eg, gambling, BED, and kleptomania).53,54 By blocking the euphoric effects of alcohol and opioids, naltrexone prevents these substances from binding to opioid receptors in the brain, thereby reducing cravings and diminishing the reinforcing effects that drive impulsive substance use.

There is some evidence suggesting that the opioid system also regulates impulsive aggression. Endogenous opioids (eg, endorphins) can enhance feelings of aggression and hostility, and opioid antagonists may help inhibit these behaviors. In conditions like IED or bipolar disorder, opioid antagonists, like naltrexone, may reduce impulsive aggression that is driven by reward-seeking behavior. Although clinical trials have had mixed results, the potential for opioid antagonists to address impulsive aggression remains an area of interest. Opioid antagonists are generally well tolerated, although they can cause liver toxicity. In addition, naltrexone may precipitate opioid withdrawal symptoms if it is taken while opioids are still in the system, so careful consideration is necessary when prescribing this agent.

Stimulants

Stimulants increase dopamine and norepinephrine levels, particularly in the PFC, which enhances executive functions (eg, attention, behavioral inhibition, and impulse control). Impulsivity is a core symptom of ADHD, and stimulants are considered the first-line treatment for this condition. By improving executive function, stimulants significantly reduce impulsivity, making it easier for individuals with ADHD to focus, plan, and manage emotional responses. Research has shown that stimulants reduce impulsive behaviors (eg, interrupting others, making snap decisions, and acting on urges). They also reduce hyperactivity by improving focus and attention, which in turn promotes more thoughtful decision-making and goal-directed behavior.

Lisdexamfetamine, a stimulant, is FDA approved for the treatment of BED and is the only medication specifically approved for this condition. While the exact mechanism of action is unclear, it is believed to involve satiety, reward, cognition, and impulsivity, likely mediated by catecholamine and serotonin pathways.71

Common adverse effects of stimulants include insomnia, hypertension, appetite suppression, anxiety, and irritability. When prescribed for ADHD, these medications may inadvertently increase impulsivity. In this case, a nonstimulant medication for ADHD (eg, atomoxetine, desipramine, clonidine, guanfacine, or bupropion) would be advised. Stimulants may provoke new-onset psychosis or exacerbate manic symptoms in those with bipolar disorder. Caution is advised when prescribing stimulants to those with a history of a SUD due to the potential for misuse, diversion, and dependence. In addition, stimulants increase heart rate and blood pressure, which requires careful monitoring in individuals with cardiovascular conditions. They may also worsen anxiety, mania, or psychosis, particularly in individuals with BPD or schizophrenia.

What Happened to Mr A?

At a follow-up visit, Mr A continued to show signs of MCI on memory testing, with escalating impulsivity (eg, compulsive gambling and increased alcohol use). Although he had a bright affect and showed no signs of depression, his daughter reported markedly out-of-character behaviors: financial recklessness, excessive online poker, and growing emotional disinhibition.

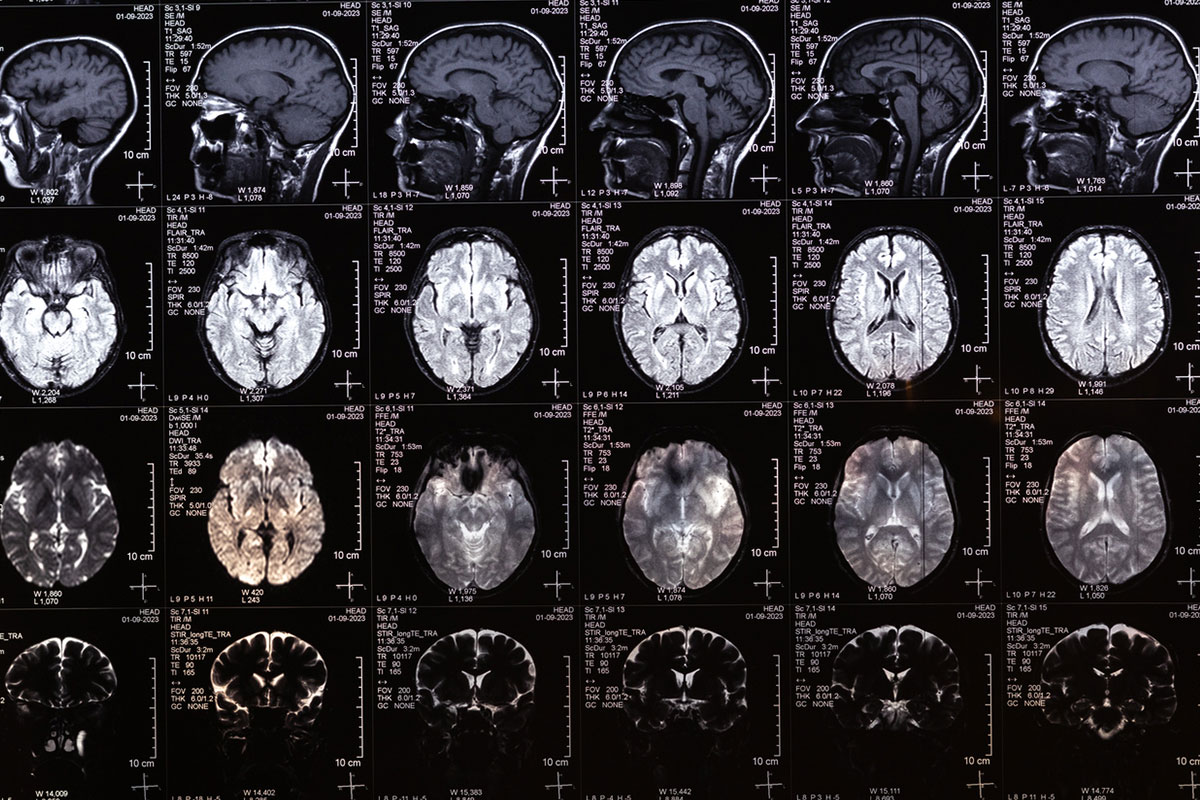

Neuropsychological testing revealed deficits in executive functioning (eg, poor inhibitory control and limited cognitive flexibility), while his memory remained relatively intact. Brain magnetic resonance imaging revealed mild bilateral frontotemporal atrophy and periventricular white matter disease, and a full laboratory panel ruled out metabolic, infectious, or nutritional contributors. Taken together, the clinical picture suggested a frontal-executive syndrome, raising concern for prodromal behavioral variant frontotemporal dementia (bvFTD).

The clinical team started naltrexone (at 25 mg/day and titrated to 50 mg/day), which helped reduce Mr A’s cravings and reward-seeking behaviors that were associated with both alcohol use and gambling, without causing sedation or liver abnormalities. Sertraline was also started and titrated upward (to 50 mg/day), which helped to address his behavioral disinhibition and stabilized his executive functioning.

Mr A engaged in a modified form of CBT, tailored to accommodate his cognitive limitations. Sessions focused on increasing his awareness of triggers, using delay and distraction techniques, and building external structure into his daily routine. Environmental safeguards were added, including caregiver-managed finances and technology-based gambling site blockers.

By his 3-month follow-up visit, Mr A had significantly reduced his alcohol intake and had not gambled in over 8 weeks. His daughter noted a return of his warmth and humor, as well as a noticeable improvement in his self-control. He remained under close outpatient follow-up, with continued CBT, medication management, and periodic monitoring for potential progression toward a diagnosis of bvFTD.

CONCLUSION

Impulsivity is a shared characteristic of myriad psychiatric and neuropsychiatric conditions throughout the lifespan, which has clear-cut treatment implications. Understanding the interplay among neurobiological and psychological factors in these disorders guides the initiation of appropriate clinical interventions. It frequently manifests as difficulty delaying gratification, impaired judgment, and failure to inhibit inappropriate actions—behaviors that can range from mildly disruptive to seriously harmful. It reflects dysfunction in multiple brain circuits, eg, the ventral frontostriatal system (that contributes to “waiting” impulsivity) and the dorsal prefrontal and inferior frontal gyrus circuits (that support inhibitory control and action monitoring, and their dysfunction leads to “stopping” impulsivity).

ADHD (which is associated with executive dysfunction) often has impairments in academic performance, social relationships, daily functioning, and self-regulation (which contributes to risk-taking behaviors and the development of SUDs). In addition, acute intoxication impairs inhibitory control and increases impulsive behaviors, while the chronic use of substances exacerbates impulsivity through neurobiological changes in the ventral tegmental area and nucleus accumbens. Whenever possible, treatments for impulsivity should target specific etiologies and symptoms.

Article Information

Published Online: February 5, 2026. https://doi.org/10.4088/PCC.25f04058

© 2026 Physicians Postgraduate Press, Inc.

Submitted: August 12, 2025; accepted October 31, 2025.

To Cite: Impulsivity: differential diagnosis, evaluation, and management. Prim Care Companion CNS Disord 2026;28(1):25f04058.

Author Affiliations: Department of Psychiatry, Harvard Medical School, Boston, Massachusetts (Matta, Stern); Massachusetts General Hospital, Boston, Massachusetts (Matta, Stern); Department of Psychiatry, Bayhealth Medical Center, Dover, Delaware (DeSimone); Department of Psychiatry, Geisel School of Medicine, Dartmouth, Lebanon, New Hampshire (Rustad); Department of Psychiatry, Larner College of Medicine, University of Vermont, Burlington, Vermont (Rustad); Burlington Lakeside VA Community Based Outpatient Clinic, Burlington, Vermont (Rustad); White River Junction VA Medical Center, White River Junction, Vermont (Rustad); Department of Mental Health and Behavioral Sciences, James A. Haley Veterans Administration Hospital, Tampa, Florida (Bobonis Babilonia); Department of Psychiatry and Behavioral Neurosciences, University of South Florida, Morsani College of Medicine, Tampa, Florida (Bobonis Babilonia); MGH-McLean Department of Psychiatry Residency Training Program, Boston, Massachusetts (Le).

Corresponding Author: Theodore A. Stern, MD, Massachusetts General Hospital, 55 Fruit St, WRN 606, Boston, MA 02114 ([email protected]).

Matta, DeSimone, Rustad, Bobonis Babilonia, and Le are co-first authors; Stern is the senior author.

Financial Disclosure: Dr Rustad is employed by the US Department of Veterans Affairs, but the opinions expressed in this presentation do not reflect those of the Department of Veterans Affairs. Dr Stern has received royalties from Elsevier for editing textbooks on psychiatry. Drs Matta, Bobonis Babilonia, and Le have no disclosures or conflicts of interest.

Funding/Support: None.

Clinical Points

- Impulsivity in older adults frequently signals an emerging neurodegenerative process and often reveals itself with explosive outbursts, behavioral disinhibition, and impulsivity.

- Managing impulsivity often involves a combination of behavioral strategies, anxiety reduction techniques, and pharmacologic interventions.

- Cognitive-behavioral therapy reduces impulsivity by helping individuals to identify and challenge the thoughts that drive impulsive behavior, develop delayed gratification skills, improve emotional regulation, and build self-control.

- Dialectical behavioral therapy treats impulsivity by teaching skills in mindfulness, distress tolerance, emotional regulation, interpersonal effectiveness, and values-based action.

- Mindfulness reduces impulsivity by enhancing awareness of thoughts and emotions, providing tools to pause before acting, improving emotional regulation, and fostering self-compassion.

- Pharmacologic treatments for impulsivity should be tailored to the specific cause if it can be identified.

References (71)

- Folstein MF, Folstein SE, McHugh PR. “Mini-Mental State”: a practical method for grading the cognitive state of patients for the clinician. J Psychiatr Res. 1975;12(3):189–198. PubMed CrossRef

- Paribello P, Manchia M, Pinna F, et al. Impulsivity, aggressivity, and mood disorders: a narrative review. J Psychopathology. 2024;30:52–72.

- Bechara A, Damasio H, Tranel D, et al. Deciding advantageously before knowing the advantageous strategy. Science. 1997;275(5304):1293–1295. PubMed CrossRef

- Barratt E, Stanford M, Felthous A, et al. The effects of phenytoin on impulsive and premeditated aggression: a controlled study. J Clin Psychopharmacol. 1997;17(5):341–349. PubMed CrossRef

- Barratt ES. Impulsiveness sub-traits: arousal and information processing. In: Motivation, emotion and personality. Elsevier Science Publishers;1985:137–146.

- Al-Hammouri MM, Rababah JA, Shawler C. A review of the concept of impulsivity: an evolutionary perspective. ANS Adv Nurs Sci. 2021;44(4):357–367. PubMed CrossRef

- Chan CC, Alter S, Hazlett EA, et al. Neural correlates of impulsivity in bipolar disorder: a systematic review and clinical implications. Neurosci Biobehav Rev. 2023;147:105–109.

- Tamam L, Bican M, Keskin N. Impulse control disorders in elderly patients. Compr Psychiatry. 2014;55(4):1022–1028. PubMed CrossRef

- Bateman DR, Gill S, Hu S, et al. Agitation and impulsivity in mid and late life as possible risk markers for incident dementia. Alzheimers Dement (N Y). 2020;6(1):e12016. PubMed CrossRef

- Jeffrey W, Dalley A, Mar DC, et al. Neurobehavioral mechanisms of impulsivity: fronto-striatal systems and functional neurochemistry. Pharmacol Biochem Behav. 2008;90(2):250–260. PubMed

- Fineberg N, Potenza MN, Chamberlain SR, et al. Probing compulsive and impulsive behaviors, from animal models to endophenotypes: a narrative review. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2009;35(3):591–604. PubMed CrossRef

- Jentsch JD, Ashenhurst JR, Cervantes MC, et al. Dissecting impulsivity and its relationships to drug addictions. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2014;1327(1):1–26. PubMed CrossRef

- Lee RSC, Hoppenbrouwers S, Franken I. A systematic meta-review of impulsivity and compulsivity in addictive behaviors. Neuropsychol Rev. 2019;29(1):14–26. PubMed CrossRef

- Migliaccio R, Tanguy D, Bouzigues A, et al. Cognitive and behavioural inhibition deficits in neurodegenerative dementias. Cortex. 2020;131:265–283. PubMed CrossRef

- Claassen D, Kanoff K, Wylie S. Dopamine agonists and impulse control disorders in Parkinson’s disease. US Neurol. 2013;9(1):13–16.

- Pai NB, Vella SL, Dawes K. The clinical assessment of impulsivity. Arch Med Health Sci. 2018;6:95–98.

- Brokke SS, Landrø NI, Haaland VØ. Impulsivity and aggression in suicide ideators and suicide attempters of high and low lethality. BMC Psychiatry. 2022;22(1):753. PubMed CrossRef

- Maurer JM, Tirrell PS, Anderson NE, et al. Dimensions of impulsivity related to psychopathic traits and homicidal behavior among incarcerated male youth offenders. Psychiatry Res. 2021;303:114094. PubMed CrossRef

- Patton JH, Stanford MS, Barratt ES. Factor structure of the Barratt Impulsiveness scale. J Clin Psychol. 1995;51(6):768–774. PubMed CrossRef

- Whiteside SP, Lynam DR. The five-factor model and impulsivity: using a structural model of personality to understand impulsivity. Personal Individ Differ. 2001;30(4):669–689. CrossRef

- Whiteside SP, Lynam DR, Miller JD, et al. Validation of the UPPS impulsive behaviour scale: a four-factor model of impulsivity. Eur J Personal. 2005;19:559–574. CrossRef

- Kirby KN, Petry NM, Bickel WK. Monetary Choice Questionnaire (MCQ) [Database record]. APA PsycTests; 1999.

- Nasreddine ZS, Phillips NA, Bédirian V, et al. The Montreal Cognitive Assessment, MoCA: a brief screening tool for mild cognitive impairment. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2005;53(4):695–699. PubMed CrossRef

- Watts TW, Duncan GJ, Quan H. Revisiting the marshmallow test: a conceptual replication investigating links between early delay of gratification and later outcomes. Psychol Sci. 2018;29(7):1159–1177. PubMed CrossRef

- Moffitt TE, Arseneault L, Belsky D, et al. A gradient of childhood self-control predicts health, wealth, and public safety. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2011;108(7):2693–2698. PubMed CrossRef

- Gilmore K, Meersand P. Normal child and adolescent development. In: Hales RR, Yudofsky SC, Roberts LW, eds. The American Psychiatric Publishing Textbook of Psychiatry. Sixth ed. American Psychiatric Publishing, Inc.; 2014:139–173.

- Ahmed SF, Kuhfeld M, Watts TW, et al. Preschool executive function and adult outcomes: a developmental cascade model. Dev Psychol. 2021;57(12):2234–2249. PubMed CrossRef

- Sarkis E. Addressing attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder in the workplace. Postgrad Med. 2014;126(5):25–30. PubMed CrossRef

- American Psychiatric Association. Attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder, bipolar and related disorders, neurocognitive disorders, personality disorders. In: American Psychiatric Association Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, ed., 5, Text Revision. (DSM-5-TR), American Psychiatric Publishing, 2022: pp 68-76, 139-176,521-542, 667-734.

- Samek DR, Hicks BM. Externalizing disorders and environmental risk: mechanisms of gene-environment interplay and strategies for intervention. Clin Pract (Lond). 2014;11(5):537–547. PubMed CrossRef

- Cheng ST. Dementia caregiver burden: a research update and critical analysis. Curr Psychiatry Rep. 2017;19(9):64. PubMed CrossRef

- Lopez PL, Torrente FM, Ciapponi A, et al. Cognitive-behavioural interventions for attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) in adults. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. March 23, 2018;3(3):CD010840. PubMed CrossRef

- Hodgins DC, Peden N. Tratamento cognitivo e comportamental para transtornos do controle de impulsos [Cognitive-behavioral treatment for impulse control disorders]. Braz J Psychiatry. 2008;30(Suppl 1):S31–S40. PubMed CrossRef

- Linehan M. DBT Skills Training Manual. 2nd ed. The Guilford Press; 2014.

- Chapman AL. Dialectical behavior therapy: current indications and unique elements. Psychiatry (Edgmont). 2006;3(9):62–68. PubMed

- Oppenauer C, Sprung M, Gradl S, et al. Dialectical behaviour therapy for posttraumatic stress disorder (DBT-PTSD): transportability to everyday clinical care in a residential mental health centre. Eur J Psychotraumatol. 2023;14(1):2157159. PubMed CrossRef

- Cavicchioli M, Movalli M, Bruni A, et al. The initial efficacy of stand-alone DBT skills training for treating impulsivity among individuals with alcohol and other substance use disorders [published correction appears in Behav Ther. 2024 Jan; 55(1): 212. Behav Ther. 2023;54(5):809–822. PubMed CrossRef

- Fleming AP, McMahon RJ, Moran LR, et al. Pilot randomized controlled trial of dialectical behavior therapy group skills training for ADHD among college students. J Atten Disord. 2015;19(3):260–271. PubMed CrossRef

- Ahmadi Tahor-Soltani M, Dabaghi P, Mohamadi A. The effectiveness of dialectical behavioral therapy (DBT) on emotion regulation and impulse control of soldiers with a self-reporting experience. J Nurse Physician Within War. 2020;8(28):12–23.

- Trunko ME, Schwartz TA, Berner LA, et al. A pilot open series of lamotrigine in DBT-treated eating disorders characterized by significant affective dysregulation and poor impulse control. Borderline Personal Disord Emot Dysregul. 2017;4:21. PubMed CrossRef

- Ding F, Wu J, Zhang Y. Can mindfulness-based stress reduction relieve depressive symptoms? A systematic review and meta-analysis. J Pac Rim Psychol. 2023;17.

- Lee YC, Chen CR, Lin KC. Effects of mindfulness-based interventions in children and adolescents with ADHD: a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2022;19(22):15198. PubMed CrossRef

- Garland EL, Howard MO. Mindfulness-based treatment of addiction: current state of the field and envisioning the next wave of research. Addict Sci Clin Pract. 2018;13(1):14. PubMed CrossRef

- Marchand WR. Neural mechanisms of mindfulness and meditation: evidence from neuroimaging studies. World J Radiol. 2014;6(7):471–479. PubMed CrossRef

- Mas-Cuesta L, Baltruschat S, Cándido A, et al. Brain changes following mindfulness: reduced caudate volume is associated with decreased positive urgency. Behav Brain Res. 2024;461:114859. PubMed CrossRef

- Lussier JP, Heil SH, Mongeon JA, et al. A meta-analysis of voucher-based reinforcement therapy for substance use disorders. Addiction. 2006;101(2):192–203. PubMed CrossRef

- Seel C, Champion H, Dorey L, et al. Contingency management for the treatment of harmful gambling: a case report. Psychiatry Res Case Rep. 2024;3(1).

- Ziser K, Resmark G, Giel KE, et al. The effectiveness of contingency management in the treatment of patients with anorexia nervosa: a systematic review. Eur Eat Disord Rev. 2018;26(5):379–393. PubMed CrossRef

- Morrison KL, Smith BM, Ong CW, et al. Effects of acceptance and commitment therapy on impulsive decision-making. Behav Modif. 2020;44(4):600–623. PubMed CrossRef

- El-Sayed MM, Elhay ESA, Taha SM, et al. Efficacy of acceptance and commitment therapy on impulsivity and suicidality among clients with bipolar disorders: a randomized control trial. BMC Nurs. 2023;22(1):271. PubMed CrossRef

- Munawar K, Choudhry FR, Lee SH, et al. Acceptance and commitment therapy for individuals having attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD): a scoping review. Heliyon. 2021;7(8):e07842. PubMed CrossRef

- Gupta S, Gargi PD. Habit reversal training for trichotillomania. Int J Trichology. 2012;4(1):39–41. PubMed CrossRef

- Tahir T, Wong MM, Maaz M, et al. Pharmacotherapy of impulse control disorders: a systematic review. Psychiatry Res. 2022;311:114499. PubMed CrossRef

- Grant J, Chamberlain S. (August 15, 2015). Psychopharmacological options for treating impulsivity. Psychiatric Times. Available at: https://www.psychiatrictimes.com/view/psychopharmacological-options-treating-impulsivity Accessed August 13, 2025.

- Felthous AR, McCoy B, Nassif JB, et al. Pharmacotherapy of primary impulsive aggression in violent criminal offenders. Front Psychol. 2021;12:744061. PubMed CrossRef

- Meyer JM, Cummings MA, Proctor G, et al. Psychopharmacology of persistent violence and aggression. Psychiatr Clin North Am. 2016;39(4):541–556. PubMed CrossRef

- Khalifa NR, Gibbon S, Völlm BA, et al. Pharmacological interventions for antisocial personality disorder. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2020;9(9):CD007667. PubMed CrossRef

- Chen A, Copeli F, Metzger E, et al. The psychopharmacology algorithm project at the Harvard South Shore Program: an update on management of behavioral and psychological symptoms in dementia. Psychiatry Res. 2021;295:113641. PubMed CrossRef

- Husa AP, Moilanen J, Murray GK, et al. Lifetime antipsychotic medication and cognitive performance in schizophrenia at age 43 years in a general population birth cohort. Psychiatry Res. 2017;247:130–138. PubMed CrossRef

- Fusaroli M, Raschi E, Giunchi V, et al. Impulse control disorders by dopamine partial agonists: a pharmacovigilance-pharmacodynamic assessment through the FDA adverse event reporting system. Int J Neuropsychopharmacol. 2022;25(9):727–736. PubMed CrossRef

- Strange BC. Once-daily treatment of ADHD with guanfacine: patient implications. Neuropsychiatr Dis Treat. 2008;4(3):499–506. PubMed CrossRef

- Mechler K, Banaschewski T, Hohmann S, et al. Evidence-based pharmacological treatment options for ADHD in children and adolescents. Pharmacol Ther. 2022;230:107940. PubMed CrossRef

- Pringsheim T, Hirsch L, Gardner D, et al. The pharmacological management of oppositional behaviour, conduct problems, and aggression in children and adolescents with attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder, oppositional defiant disorder, and conduct disorder: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Part 1: psychostimulants, alpha-2 agonists, and atomoxetine. Can J Psychiatry. 2015;60(2):42–51. PubMed CrossRef

- London EB, Zimmerman-Bier BL, Yoo JH, et al. High-dose propranolol for severe and chronic aggression in autism spectrum disorder: a pilot, double-blind, placebo-controlled, randomized crossover study. J Clin Psychopharmacol. 2024;44(5):462–467. PubMed CrossRef

- Mohammadzadeh S, Ahangari TK, Yousefi F. The effect of memantine in adult patients with attention deficit hyperactivity disorder. Hum Psychopharmacol. 2019;34(1):e2687. PubMed CrossRef

- Elias AM, Pepin MJ, Brown JN. Adjunctive memantine for opioid use disorder treatment: a systematic review. J Subst Abuse Treat. 2019;107:38–43. PubMed CrossRef

- Khan S, Ali AS, Kadir B, et al. Effects of memantine in patients with traumatic brain injury: a systematic review. Trauma Care. 2021;1(1):1–14. CrossRef

- Lee DK, Lipner SR. The potential of n-acetylcysteine for treatment of trichotillomania, excoriation disorder, onychophagia, and onychotillomania: an updated literature review. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2022;19(11):6370. PubMed CrossRef

- Sharma R, Tikka SK, Bhute AR, et al. N-acetyl cysteine in the treatment of cannabis use disorder: a systematic review of clinical trials. Addict Behav. 2022;129:107283. PubMed CrossRef

- Felthous AR, Stanford MS. A proposed algorithm for the pharmacotherapy of impulsive aggression. J Am Acad Psychiatry L. 2015;43(4):456–467. PubMed

- Schneider E, Higgs S, Dourish CT. Lisdexamfetamine and binge-eating disorder: a systematic review and meta-analysis of the preclinical and clinical data with a focus on mechanism of drug action in treating the disorder. Eur Neuropsychopharmacol. 2021;53:49–78. PubMed CrossRef

Enjoy this premium PDF as part of your membership benefits!