Lessons Learned at the Interface of Medicine and Psychiatry

The Psychiatric Consultation Service at Massachusetts General Hospital sees medical and surgical inpatients with comorbid psychiatric symptoms and conditions. During their twice-weekly rounds, Dr Stern and other members of the Consultation Service discuss diagnosis and management of hospitalized patients with complex medical or surgical problems who also demonstrate psychiatric symptoms or conditions. These discussions have given rise to rounds reports that will prove useful for clinicians practicing at the interface of medicine and psychiatry.

Prim Care Companion CNS Disord 2026;28(1):25f04082

Author affiliations are listed at the end of this article.

Have you ever struggled over deciding what to say while your patient is dealing with the death of a loved one? Have you been uncertain about whether and when acute grief morphs into major depressive disorder (MDD)? Have you wondered whether you should prescribe medications to relieve your patient’s distress or to help them sleep? If you have, the following case vignette and discussion should prove useful.

CASE VIGNETTE

Ms A, a 51-year-old divorced high school teacher, has been distraught since the tragic death of her 28-year-old daughter in a motor vehicle accident 3 weeks earlier. She has been inconsolable, crying for hours on end; in addition, she has been having difficulty sleeping, has not been eating well, and has been preoccupied with reconnecting with her daughter. Moreover, she says that she is unsure if or how she will recover from this loss. Her mother has been staying with her to provide her with support. Ms A had a 2-month episode of MDD surrounding her divorce 3 years earlier that improved with counseling.

DISCUSSION

What Is Grief, and How Is It Manifest?

Grief and bereavement are closely related conditions that occur in the context of loss. However, these terms differ in their meaning and scope. According to the American Psychological Association, grief refers to the emotional distress or “anguish experienced after significant loss” or change.1 Grief is characterized by profound sadness and a yearning or longing for what has been lost. Grief is common following the death of a significant loved one. Other types of loss (eg, the break-up of a relationship, the loss of a job, or the diagnosis of serious illness) can also prompt a grief reaction. Although grief is typically painful and isolating, it is a normal response to loss, and most people cope with loss without requiring professional intervention.2 Grief is a process of adjusting to change that is triggered by loss.3 How a person grieves depends largely on the way they have coped with other issues in their life, their personality, their relationship with the deceased, and the circumstances surrounding their loved one’s death. Recent research has attempted to define healthy and pathological grief.

On the other hand, bereavement refers specifically to the “condition of having lost a loved one to death.”1 Bereavement is the period or state of loss that results from death, while grief is the emotional reaction to it. Bereavement is a complex, multidimensional process that involves the physical, psychological, spiritual, and sociological dimensions of the human experience.4 Individual differences, including cultural differences, increase the complexity of bereavement and call for a tailored approach to caring for the bereaved. Following the death of a loved one, the bereaved must adjust to the physical absence of their loved one and to the associated changes in their life, which, for some, can take months or even years.5 Although bereaved individuals had been encouraged to disconnect emotionally from their loved one,6 the current focus of clinical interventions involves helping the bereaved adapt to life without their loved one, while maintaining a bond with them.7

One of the hardest things for recently bereaved individuals is not knowing what to expect. They often question whether what they are experiencing is “normal,” especially if this represents their first significant loss. In the initial weeks after a death, they are likely to develop a myriad of physical and emotional reactions, including disturbances of appetite and sleep, impaired concentration, and yearnings for the deceased. Many people describe feeling as though they are on “automatic pilot” (ie, going through the motions as they attend to administrative and legal tasks). It is common for many bereaved individuals to feel as though they are “getting worse” about 4–6 weeks after experiencing their loss. This period usually coincides with waning family support and coming to grips with their loved one’s death. They might develop intense sadness, yearn for the deceased, feel anxious about the future, and question what they could have done differently.8

Primary care providers (PCPs), by the nature of their relationship with a bereft patient, are well positioned to assess bereavement risk and provide education and guidance about what to expect in the months that follow loss, which can facilitate coping. This approach helps to mitigate the reaction to loss, especially given that many bereaved individuals and those who support them believe that grief will improve progressively. However, grief tends to come in waves.3 Many people also inaccurately believe that they must go through all 5 stages of grief (eg, denial, anger, bargaining, depression, and acceptance),9 as was originally described for individuals with a terminal illness.10

A more modern model (the dual process model of coping with bereavement) helps people understand grief that follows death. This model posits that healthy grieving involves the oscillation between loss-oriented coping (eg, yearning or crying for the deceased) and restoration-oriented coping (eg, investing in new roles and responsibilities).11 Moreover, the cultural context of bereavement plays a substantial role in mourning,12,13 as some individuals express grief outwardly (through weeping or partaking in religious rituals), while others grieve privately. In Western societies, there is a tendency to believe that grief will resolve quickly and that the bereaved will be “back to normal” in a matter of weeks. For the bereaved, life is forever changed following the death of their loved one. Grieving requires that patients adapt while clinicians facilitate such adaptation so that the bereaved can continue to live a fulfilling life, even though it may not be the life that they had originally expected.8

Grief’s manifestations also depend on the meaning of the loss and the individual’s relationship to the person who has died. Some individuals develop anticipatory grief, or distress that occurs before an expected loss.14 For example, family caregivers of a patient with impaired cognition often report anticipatory grief in response to their loved one’s loss of functioning, ahead of their actual demise.15 When a person does not have societies’ permission to express grief openly (such as when grieving the loss of a pet or of a nontraditional relationship), they may develop disenfranchised grief, or a grief response that remains hidden.16 Even though most individuals adapt to the loss of their loved one over time, recent research reveals that for a significant subset, grief may become pathological (ie, marked by intense, disabling distress that persists for an abnormally prolonged period).17,18

Who Suffers From Grief?

Grief is a near-universal experience that emerges after the loss of a significant attachment, most commonly the death of a loved one. In fact, even social animals (eg, primates and elephants) experience grief, manifest by withdrawal, vocal distress, or remaining close to the deceased.19 Expression of grief varies given differences in cultural norms, personality traits (eg, the ability to find meaning from a loss), psychiatric conditions, cognitive appraisals, experience with loss, anticipation of the loss, and social supports.12,20–24 Grief is most likely to develop when deep emotional bonds had been established with the deceased.25 The degree to which one adapts to loss is also influenced by an individual’s attachment style; individuals with secure attachments typically show more adaptive coping strategies than those with insecure (ie, anxious, avoidant, disorganized) attachments.26

How Does Acute Grief Differ From Persistent or Complicated Grief Reactions?

Although most bereaved individuals are expected to cope well with loss,27 approximately 7%–10% 2,28 develop complex and intense grief that disrupts their daily functioning, which can be classified as prolonged grief disorder (PGD).29 The prevalence of prolonged grief may be even higher among those who experienced sudden and traumatic loss of their loved one (eg, following an accident or suicide).28 Complicated grief30 is another term often used by mental health professionals to describe complex grief. PGD is a distinct and separate condition from depression, anxiety, and posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD),18,31 and it was added to the International Classification of Diseases, Eleventh Revision.32 Although a similar condition, persistent complex bereavement disorder, was described in the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual for Mental Disorders (DSM) as a category of further study,33 recent research led to the inclusion of PGD in the DSM-5-TR in 2022.34,35

PGD can be distinguished from normative or uncomplicated grief by the persistent difficulty of accepting the death or by not believing that the death occurred. Diagnosing PGD in adults requires that the death occurred at least 12 months earlier, while for children and adolescents, the death must have taken place at least 6 months earlier. The bereaved must have at least 3 of the following symptoms nearly every day for at least the last month before the diagnosis can be made35:

- An identity disruption (eg, feeling as though a part of oneself has died)

- An intense disbelief about the death

- Avoidance of reminders that the person has died

- Intense emotional pain (eg, anger, bitterness, sorrow) related to the death

- Difficulty with reintegration (eg, problems engaging with social interests or planning)

- Emotional numbing (an absence or a marked reduction of emotions)

- Feeling that life is meaningless

- Intense loneliness (feeling alone or detached from others).

The diagnosis also requires substantial and impaired functioning and circumstances in which the bereaved person’s grief extends beyond what might be expected based on social, cultural, or religious norms. Some bereaved individuals, especially those who have other risk factors for grief (eg, other recent losses), could have severe long-term psychological and physical problems (eg, generalized anxiety, depression, cardiovascular and immune system-related illnesses, insomnia, and a higher risk for suicide).36–38

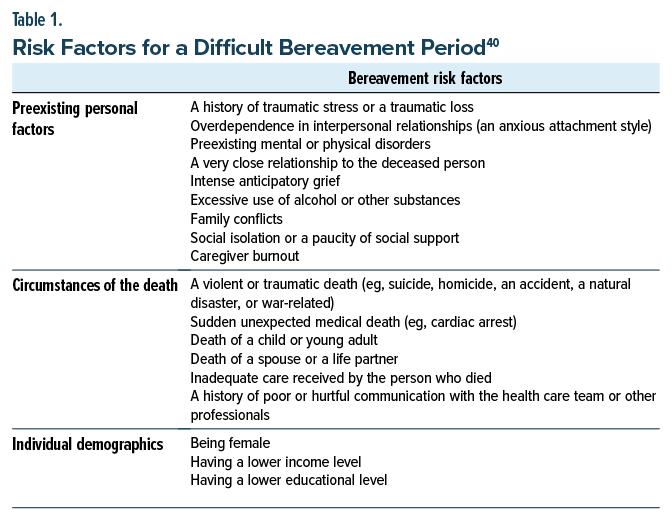

Which Factors Increase One’s Risk for a Difficult Bereavement Period?

The severity and the expression of grief depend on many factors (eg, one’s relationship with the deceased, the circumstances of the death, prior losses, and the bereaved person’s mental health history).39 Table 1 summarizes the most salient risk factors for bereavement.40

How Does the Reaction to Sudden Loss Differ From Death That Follows a Chronic Illness or Advanced Age?

Bereaved individuals who experienced a sudden, unexpected, or traumatic death of their loved one (eg, due to an accident, a natural disaster, war-related death, an overdose, suicide, homicide) are at increased risk of poor bereavement outcomes, including a higher likelihood of developing PGD.28 Further, sudden and unexpected losses contribute to poor mental health outcomes (eg, PTSD, MDD, and anxiety-related disorders).41,42 Not surprisingly, individuals whose loved one died as a result of a chronic illness or advanced age often have time to adjust to the reality of the impending death, whereas that is not the case with sudden death. In addition, with sudden death, there is no opportunity to say “goodbye” to their loved one, and “unfinished” business may remain unresolved.43

How Does Dealing With the Death of One’s Child Differ From the Death of Other Loved Ones?

The death of one’s child is often considered to be one of the worst losses a person can suffer because it occurs “out of order” and challenges the notion that parents should protect their children.44 When death occurs prematurely, as with the death of a child or a young adult, those who have been impacted mourn the deceased and the life they have yet to live (eg, seeing them graduate from college or becoming a parent).

How Long Should Grief Last?

Most people want to know that there will be an end to their pain and how long it will last. However, given the variability of social supports and the coping styles of the bereft, it is difficult to predict how long grief will last. Typically, grief presents itself in waves, and it dissipates over time. Waves are often triggered by memories, thoughts, and events or significant dates. Some “triggers” can be anticipated (eg, the loved one’s birthday, the anniversary of the death), while others can arise out of the blue (eg, hearing a song on the radio or seeing someone for the first time after the death).3 Knowing that grief comes in waves, with different triggers, helps to explain why individuals who are grieving for the same loved one will have different grief experiences.

How Might I Feel When I Learn About the Death of My Patient’s Loved One?

Upon learning that a patient and their family are dealing with the sudden death of a loved one, clinicians should expect to have intense feelings (eg, shock, devastation, disbelief) that often mirror the patients’ emotions. Such news might trigger recollections of our losses, making it difficult to know what to say or do. Moreover, hearing devastating news frequently can interfere with the integration of what we have just been told. This is normal and expected.

How Can I Acknowledge Loss, Legitimize It, Express My Sorrow, and Facilitate the Coping of Patients and Their Family Members?

Caring for patients requires that clinicians must deal with their own emotions. By allowing for reflection, clinicians can integrate tragic news and convey to their patient that they are there for them. It is often prudent to acknowledge the loss (eg, “This is devastating news”) and then shepherd the patient to a private place where you can both sit down to talk. Then, gentle exploration can follow, clarifying which emotions and concerns have surfaced. Not uncommonly, silence can be therapeutic; waiting for the patient to speak allows them to focus on the next steps (eg, “Tell me more about that” or “I can’t imagine how overwhelming this must feel”). By being empathic and expressing empathy, clinicians align themselves with their patient’s needs, which might include telling you their story. If a clinician has already learned what has transpired and is planning to make a bereavement call, it can help to have another member of the team (eg, a nurse, social worker, or other staff member who knows the patient) join the call to debrief later about the events.

Should I Reassure My Patient and Their Family Members and Tell Them That They Will Feel Better?

When and how much you should reassure your patient often depends on the situation and how your patient has coped with other life difficulties. The goal is to “hold hope” in the room—that over time, the waves of grief will lessen—while acknowledging how painful the loss has been. Patients should also be encouraged to follow a daily routine and pay attention to their own personal hygiene and well-being. It is also helpful to socialize with friends and family who are supportive. Recently bereaved people often say that even though interacting with others was difficult at first, they felt better afterward. Support through local community or hospice bereavement groups can also add another layer of support.

Should I Ask My Patient to Provide Details That Surrounded the Death of Their Loved One?

Many patients want to tell you what happened surrounding the death. Therefore, you should be available to them and not appear rushed. It often helps to ask: “Could you tell me a little bit about what happened?” Enough time should be carved out to enumerate resources and provide next steps about future appointments or contacts.

What Can I Suggest My Patient Do In the Early Months After Their Loss?

In the initial weeks and months following a loss, it is helpful to suggest to patients that they follow the “3 S’s”—structure and routine, self-care, and social connections. Having a daily routine provides structure even if they do not feel like doing anything. Other recommendations include the following:

- Paying attention to their sleep—anchoring their bed and awake times—even though some sleep disturbance is normal in the first few weeks

- Trying to eat regularly throughout the day even if they have little appetite

- Planning to do something each day, gradually reengaging in regular activities

- Writing a daily “to-do list,” as this can help them feel a little more in control

- Accepting invitations from friends and family whose company they usually enjoy and who are supportive

- Including walking or exercise in their daily routine

- Avoiding excessive alcohol use.

Making an early referral to a grief counselor, such as a clinical social worker, can provide another layer of support, especially for those individuals for whom the deceased was the primary decision-maker or where there was conflict in the family. Many bereaved individuals also benefit from joining a bereavement support group through a local hospice or other nonprofit organization. Other recommendations for support include seeking help from legal or financial advisors or local organizations, such as councils on aging, or church or faith-based groups.

When there are children or young adults in the family, it is important to help parents identify developmentally appropriate resources. It helps to encourage parents to tell children the truth about the death in language that they can understand, using accurate terms.

Other suggestions for supporting bereaved children include the following:

- Encourage children and adolescents to ask questions

- Answer their questions honestly and accurately

- Tell them it is okay to be sad and cry

- Include children and adolescents in the funeral arrangements where possible

- Realize that adolescents may only want to participate from afar, which is normal and expected

- Inform the school counselor about what has happened

- Find a bereavement support group or camp for children and adolescents

- Create family traditions that help children maintain a connection with the deceased

- Continue to share stories about the deceased in years to come.

What Is the Role of Psychopharmacology in the Management of Grief?

Although grief is a normal response to loss (due to death, injury, insult, illness, or alienation), not everyone grieves in the same manner. Grief’s intensity (eg, of agitation, weeping, hopelessness, helplessness) is typically proportionate to the disruption caused by the loss.45 Pharmacologic interventions may mitigate grief’s symptoms, but they do not resolve the core experience of loss. In some circumstances, temporary symptomatic relief (eg, with a benzodiazepine that can help the bereaved sleep more soundly) may be reasonable, but extended pharmacologic courses are not advised. However, when a comorbid condition has been exacerbated (eg, PTSD in cases of loss due to trauma, or a recurrence of MDD), treatment of the comorbid condition is indicated.46 Screening for well-known and prevalent conditions (eg, MDD and PTSD) should always be considered when the history or description of symptoms suggest that such disorders are present. They should be screened for with validated screening tools (eg, the PHQ-9) and trigger a search for symptoms that might facilitate making a diagnosis of 1 or more common conditions.

When Should My Grieving Patient Receive Psychiatric Treatment?

Most individuals who are grieving do not require professional help. However, when the intensity or duration of grieving (beyond weeks or months) continues to destabilize an individual and to disrupt their normal routines, a referral for professional assistance (eg, involving support, psychotherapy such as cognitive-behavioral therapy [CBT], and psychopharmacology) should be considered. In addition, referral is appropriate when thoughts of rejoining the deceased (eg, thoughts of suicide) appear or a cluster of symptoms consistent with MDD (eg, despair, self-blame/guilt) or PTSD (eg, avoidance of circumstances that remind the individual of the loss) escalate. In the case of PGD, when the symptoms of intense, debilitating grief extend beyond 12 months, patients should be referred to clinicians trained in PGD treatment (see https://prolongedgrief.columbia.edu/).

What Happened to Ms A?

Ms A’s PCP listened attentively and empathically, which was appreciated by Ms A. However, given her history of MDD and her ambiguous statement about being unsure as to whether she would be able to get through this loss, her PCP referred her to a psychiatrist to evaluate whether she was developing a recurrence of MDD or was experiencing a severe grief reaction. Given that she was not reporting self-blame or having somatic preoccupation and that she still had energy and was able to concentrate, antidepressants were not recommended. Instead, referral to a grief counselor was arranged, and Ms A used CBT successfully with resolution of her symptoms over the next 3 months. Later, her grief counselor encouraged her to join a support group for parents who also had experienced the death of a child, which she found very helpful in tackling her feelings of isolation.

CONCLUSION

Bereavement is a normal yet expected response to the death of a significant loved one that varies greatly between individuals and across cultures. It is a complex, multidimensional process that involves the physical, psychological, spiritual, and sociological dimensions of the human experience. Grief’s manifestations depend on the meaning of the loss to the individual and their relationship to the person who has died. Its expression varies given differences in cultural norms, personality traits (eg, the ability to find meaning from a loss), psychiatric conditions, cognitive appraisals, experience with loss, anticipation of the loss, and social supports. Typically, grief comes in waves, and it dissipates over time.

By virtue of the relationship between a PCP and their patients, PCPs can play an important role in helping a recently bereaved individual adapt to their loss. Providing education and guidance about what to expect, assessing bereavement risk, and providing early support can mitigate a complicated or prolonged bereavement.

Article Information

Published Online: January 29, 2026. https://doi.org/10.4088/PCC.25f04082

© 2026 Physicians Postgraduate Press, Inc.

Submitted: September 12, 2025; accepted November 11, 2025.

To Cite: Khanna GJ, Schaefer KG, Willis KD, et al. Managing grief and bereavement. Prim Care Companion CNS Disord 2026;28(1):25f04082.

Author Affiliations: Department of Psychiatry, Harvard Medical School, Boston, Massachusetts (Khanna, Morris, Stern); Department of Supportive Oncology, Dana-Farber Cancer Institute, Boston, Massachusetts (Khanna, Morris); Care Dimensions, Danvers, Massachusetts (Schaefer); Department of Psychiatry, Massachusetts General Hospital, Boston, Massachusetts (Willis, Stern).

Khanna, Schaefer, and Willis are co-first authors; Morris and Stern are co-senior authors.

Corresponding Author: Sue E. Morris, PsyD, Department of Supportive Oncology, Dana-Farber Cancer Institute, 450 Brookline Ave JF707C, Boston, MA 02215 ([email protected]).

Financial Disclosure: Dr Morris receives royalties from Hachette UK for her self-help books on grief. Dr Stern has received royalties from Elsevier for editing textbooks on psychiatry. Drs Khanna, Schaefer, and Willis have nothing to disclose.

Funding/Support: None.

Clinical Points

- Grief that follows the death of a loved one is a normal and expected reaction; however, it remains an intensely painful and isolating experience for many people.

- Grief tends to be experienced in waves that eases over time; it is neither linear nor are there set stages that must be achieved.

- In the initial months after a loss, the bereaved individual should follow the “3 S’s”: structure and daily routine, self- care, and social connections.

- Risk factors that predispose to complicated grief include past psychiatric conditions, especially depression or substance use, unexpected death, the death of a child, and poor social support.

- The goal is to help the bereaved build a new life without their loved one while maintaining a connection with them that is now based on memory and legacy.

References (46)

- American Psychological Association. Grief. In: APA Dictionary of Psychology; 2018.

- Aoun SM, Breen LJ, Howting DA, et al. Who needs bereavement support? A population-based survey of bereavement risk and support need. PLoS One. 2015;10(3):e0121101. PubMed CrossRef

- Morris S. Overcoming Grief: A Self-Help Guide Using Cognitive Behavioural Techniques. 2nd ed. Little, Brown Book Group; 2018.

- Sanders CM. Risk Factors in Bereavement Outcome. In: Stroebe MS, Stroebe W, Hansson RO, eds. Handbook of Bereavement: Theory, Research, and Intervention. Cambridge University Press; 1999:255–267.

- Stroebe M, Schut H, Stroebe W. Health outcomes of bereavement. Lancet. 2007;370(9603):1960–1973. PubMed CrossRef

- Jordan JR, Neimeyer RA. Historical and Contemporary Perspectives on Assessment and Intervention. In: Balk D, ed. Handbook of Thanatology: The Essential Body of Knowledge for the Study of Death, Dying, and Bereavement. Association for Death Education and Counseling. The Thanatology Association; 2007:213–225.

- Klass D, Silverman PR, Nickman S. Continuing Bonds: New Understandings of Grief. Taylor & Francis; 2014.

- Morris S, Block S. Grief and Bereavement. In: Grassi L, Riba M, eds. Clinical Psycho-Oncology: An International Perspective. Wiley-Blackwell; 2012:271–280.

- Kübler-Ross E. On Death and Dying. Routledge; 1969.

- Avis KA, Stroebe M, Schut H. Stages of grief portrayed on the internet: a systematic analysis and critical appraisal. Front Psychol. 2021;12:772696. PubMed CrossRef

- Stroebe M, Schut H. The dual process model of coping with bereavement: Rationale and description. Death Stud. 1999;23(3):197–224. PubMed CrossRef

- Rosenblatt PC. Grief across cultures: a review and research agenda. 2008.

- Stroebe M, Schut H. Culture and grief. Bereave Care. 1998;17(1):7–11. CrossRef

- Raphael B. The Anatomy of Bereavement: A Handbook for the Caring Professions. Routledge; 2003.

- Türk U, Aydemir MÇ, Özel-Kizil ET, et al. A comparative study of anticipatory grief in caregivers of patients with Alzheimer’s disease and hematological malignancy. J Acad Consultation-Liaison Psychiatry. 2025;66(4):320–330.

- Doka KJ. Disenfranchised grief. Bereave Care. 1999;18(3):37–39.

- Jacobs S.. Pathologic Grief: Maladaptation to Loss. American Psychiatric Association; 1993.

- Prigerson HG, Horowitz MJ, Jacobs SC, et al. Prolonged grief disorder: psychometric validation of criteria proposed for DSM-V and ICD-11. PLoS Med. 2009;6(8):e1000121. PubMed CrossRef

- King BJ. How Animals Grieve. University of Chicago Press; 2013. CrossRef

- Bonanno GA, Kaltman S. Toward an integrative perspective on bereavement. Psychol Bull. 1999;125(6):760–776. PubMed CrossRef

- Keesee NJ, Currier JM, Neimeyer RA. Predictors of grief following the death of one’s child: the contribution of finding meaning. J Clin Psychol. 2008;64(10):1145–1163. PubMed CrossRef

- Lobb EA, Kristjanson LJ, Aoun SM, et al. Predictors of complicated grief: a systematic review of empirical studies. Death Stud. 2010;34(8):673–698. PubMed CrossRef

- Mancini AD, Bonanno GA. Predictors and parameters of resilience to loss: toward an individual differences model. J Personal. 2009;77(6):1805–1832. PubMed CrossRef

- Meij WD, Stroebe M, Schut H, et al. Couples at risk following the death of their child: predictors of grief versus depression. J Consult Clin Psychol. 2005;73(4):617–623. PubMed CrossRef

- Bowlby J. Attachment and Loss: Volume III: Loss, Sadness and Depression. In: Attachment and Loss: Volume III: Loss, Sadness and Depression. The Hogarth Press and the Institute of Psychoanalysis; 1980:1–462.

- Fraley RC, Bonanno GA. Attachment and loss: a test of three competing models on the association between attachment-related avoidance and adaptation to bereavement. Personal Soc Psychol Bull. 2004;30(7):878–890. PubMed CrossRef

- Bonanno GA, Wortman CB, Nesse RM. Prospective patterns of resilience and maladjustment during widowhood. Psychol Aging. 2004;19(2):260–271. PubMed CrossRef

- Szuhany KL, Malgaroli M, Miron CD, et al. Prolonged Grief Disorder: Course, Diagnosis, Assessment, and Treatment. American Psychiatric Publishing; 2021:161–172. CrossRef

- Maciejewski PK, Prigerson HG. Prolonged, but not complicated, grief is a mental disorder. Br J Psychiatry. 2017;211(4):189–191. PubMed CrossRef

- Shear MK, Bloom CG. Complicated grief treatment: an evidence-based approach to grief therapy. J Rational-Emotive Cogn-Behav Ther. 2017;35(1):6–25.

- Boelen PA, Lenferink LI, Nickerson A, et al. Evaluation of the factor structure, prevalence, and validity of disturbed grief in DSM-5 and ICD-11. J Affect Disord. 2018;240:79–87. PubMed CrossRef

- World Health Organization. ICD-11: International Classification of Diseases (11th revision). World Health Organization. 2022.

- American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders. American Psychiatric Association; 2013.

- Boelen PA, Eisma MC, Smid GE, et al. Prolonged grief disorder in section II of DSM-5: a commentary. Eur J Psychotraumatology. 2020;11(1):1771008. PubMed CrossRef

- American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders. Fifth Edition, Text Revision (DSM-5-TR®). American Psychiatric Association; 2022.

- Morina N, Von Lersner U, Prigerson HG. War and bereavement: consequences for mental and physical distress. PLOS One. 2011;6(7):e22140. PubMed CrossRef

- Ott CH. The impact of complicated grief on mental and physical health at various points in the bereavement process. Death Stud. 2003;27(3):249–272. PubMed CrossRef

- Pohlkamp L, Kreicbergs U, Sveen J. Bereaved mothers’ and fathers’ prolonged grief and psychological health 1 to 5 years after loss—a nationwide study. Psycho-Oncology. 2019;28(7):1530–1536. PubMed CrossRef

- Carmassi C, Bertelloni CA, Dell’Osso L. Grief Reactions in Diagnostic Classifications of Mental Disorders. In: Bui E, ed. Clinical Handbook of Bereavement and Grief eactions. Humana Press; 2018:301–332.

- Simon NM, Shear MK. Prolonged grief disorder. N Engl J Med. 2024;391(13):1227–1236. PubMed CrossRef

- Van Ameringen M, Mancini C, Patterson B, et al. Post-traumatic stress disorder in Canada. CNS Neurosci Ther. 2008;14(3):171–181. PubMed CrossRef

- Keyes KM, Pratt C, Galea S, et al. The burden of loss: unexpected death of a loved one and psychiatric disorders across the life course in a national study. Am J Psychiatry. 2014;171(8):864–871. PubMed CrossRef

- Hofmann L, Merkl A, Wagner B. Unfinished business in suicide bereavement: predicting prolonged grief, PTSD, depression, and guilt. Death Stud. 2025:1–10. PubMed CrossRef

- Morris S, Fletcher K, Goldstein R. The grief of parents after the death of a young child. J Clin Psychol Med Settings. 2019;26(3):321–338. PubMed CrossRef

- Weisman A. Acute Grief. In: Stern TA, Herman JB, Slavin PL, eds. The MGH Guide to Psychiatry in Primary Care. McGraw-Hill; 1998:177–180.

- Stern TA, Powell AD. Grief, Bereavement, and Adjustment Disorders. In: Stern TA, Wilens TE, Fava M, eds. Massachusetts General Hospital Comprehensive Clinical Psychiatry. 3rd ed. Elsevier; 2015:406–410. CrossRef

Enjoy this premium PDF as part of your membership benefits!